Abstract

We evaluated the effectiveness of a stimulus pairing observation procedure to facilitate tact and listener relations in preschool children learning a second language. This procedure resulted in the establishment of most listener relations as well as some tact relations. Multiple-exemplar training resulted in the establishment of most of the remaining relations. The implications for the use of these procedures to establish simple vocabulary skills in children are discussed.

Keywords: preschool children, second language, stimulus pairing, stimulus pairing observation procedure, verbal behavior

Procedures to teach stimulus equivalence relations, which by definition involve some relations that are not taught directly, typically have involved conditional discrimination training. However, another procedure, previously referred to as respondent-type training (Leader, Barnes, & Smeets, 1996) or more recently as a stimulus pairing observation procedure (SPOP; Smyth, Barnes-Holmes, & Forsyth, 2006), also has received some empirical support. The distinguishing feature of this procedure is that no overt selection response is required during training. Rather, participants are exposed to stimuli with an intertrial interval (ITI) both within and between the presentations of pairs of related stimuli. SPOP has demonstrated efficacy in establishing skills such as derived fraction-decimal relations in typically developing children (Leader & Barnes-Holmes, 2001a). Results of studies comparing match to sample and SPOP in the establishment of derived relations have been inconsistent (Clayton & Hayes, 2004; Leader & Barnes-Holmes, 2001b), suggesting that additional research is needed. The SPOP has the advantage of being straightforward and easy to implement. It also resembles naturally occurring learning opportunities that children are likely to encounter (e.g., observing adults and peers manipulating and tacting items). The present investigation was designed to evaluate the utility of SPOP for teaching a small English vocabulary to typically developing preschool children whose first language was Spanish. We implemented multiple-exemplar training (MET; Greer, Stolfi, Chavez-Brown, & Rivera-Valdes, 2005) if derived tact and listener relations did not emerge following SPOP.

METHOD

Participants, Setting, and Stimulus Materials

Three typically developing children (3 to 4 years old) whose first language was Spanish were recruited from a local Head Start program. Sessions were conducted four to five times per week for 45 to 60 min per day in a quiet area of the school. Short breaks (2 to 3 min) were earned via a token system and interspersed throughout teaching sessions. During breaks, participants were provided with a choice of at least two preferred leisure items or toys that were identified via a paired-choice preference assessment (Fisher et al., 1992).

Three four-item stimulus sets were used to test the emergence of listener and tact relations. Nine additional four-item sets were used during MET (information on stimuli is available from the first author). Names of all items used during training were one to three syllables in length (e.g., flag, bee, eraser) and were not easily translated due to formal similarities (e.g., car was excluded because it is too similar to the Spanish word carro). A stimulus placement board was created for presentation of items during test trials. Pictures of similar but not identical stimuli were used during generalization probes.

Dependent Measure and Interobserver Agreement

The primary dependent variable was the percentage of correct tact and listener responses during pre- and posttraining probes in the absence of reinforcement. Observers scored correct tact responses if the participants said the correct name of an item in English within 5 to 10 s of presentation and the instruction “What is this?” provided in English. The observers scored correct listener responses if the participant pointed to or handed the experimenter the correct stimulus within 5 to 10 s of an instruction provided in English (e.g., “Where is —?”) and simultaneous presentation of four comparison stimuli. Sessions were videotaped for the purpose of determining interobserver agreement and treatment integrity. Agreement was calculated on a trial-by-trial basis by dividing the number of agreements by agreements plus disagreements and converting this number to a percentage. Treatment integrity was calculated by dividing the number of correct responses performed by the experimenter by the total number of possible responses and converting this number to a percentage (scored on a checklist created for this project). A second observer recorded participant and experimenter responses during 42% of sessions for Cecelia (mean agreement was 99%; range, 96% to 100%); 40% of sessions for Jason (mean agreement was 94%; range, 94% to 100%); and 37% of sessions for Myra (mean agreement was 99%; range, 88% to 100%). The mean percentage of treatment integrity was 99% (range, 99% to 100%) for Cecelia; 99% (range, 94% to 100%) for Jason; and 100% for Myra.

Design and Procedure

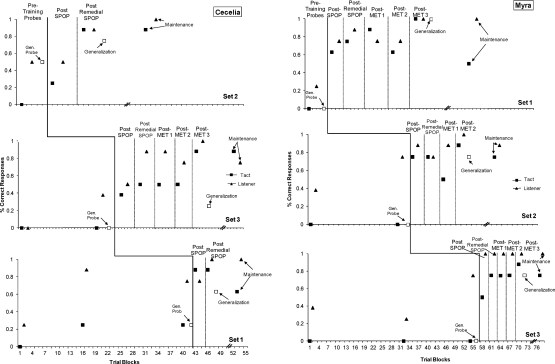

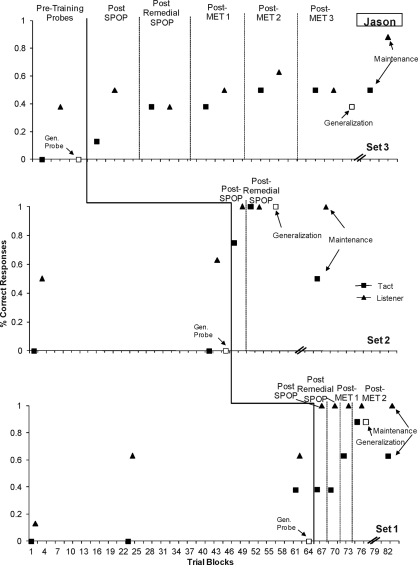

A multiple-probe design across stimulus sets was employed, with the training order of stimulus sets counterbalanced across participants (training sets were presented in the order depicted in Figures 1 and 2). We conducted pretraining probes initially for all training sets (i.e., Sets 1 through 3), followed by the SPOP for the first set selected for each participant. Posttraining probes were conducted immediately following the predetermined SPOP and remedial SPOP trial blocks for each stimulus set. Remedial SPOP (identical to the original SPOP) was conducted if participants failed initial posttraining probes for listener or tact relations. Following remedial training, participants were reexposed to posttraining probes. All other stimulus sets (denoted as MET1, MET2, MET3 in Figures 1 and 2) were employed only as needed during the MET phase of the study. MET was implemented following the SPOP if a participant failed to meet the mastery criterion for the emergence of tact or listener relations (i.e., seven correct responses in one trial block). All trial blocks throughout the study consisted of eight trials, with each stimulus presented twice.

Figure 1.

Percentage of correct responses on all probes for listener and tact relations for Cecelia and Myra.

Figure 2.

Percentage of correct responses on all probes for listener and tact relations for Jason.

Pre- and posttraining probes

Participants were first assessed on correct pronunciation of all to-be-trained vocal responses via echoic pretests. Words that the participant could not pronounce were replaced. We then conducted pretraining probes for all tact and listener relations in one eight-trial block per stimulus set, with tact probes always conducted first. The onset of tact trials was marked by the experimenter presenting one stimulus with the instruction “What is it?” provided in English. One additional probe (i.e., “What is it in English?”) was provided if the participant named the item correctly in Spanish. The onset of listener trials was marked by the experimenter saying the name of the item for that trial in English, or giving the instruction “Where is —?” or “Point to —” in English, and presenting four comparison stimuli in a table-top simultaneous match-to-sample format. The presentation of items and trials was randomized prior to each session, and all pre- and posttraining probes were conducted under extinction. Cooperation was differentially reinforced with descriptive social praise (e.g., “I like how you are paying attention!”). Generalization probes were conducted in the same manner as test probes, but with pictorial stimuli.

Stimulus pairing observation procedure

After ensuring that the participant was attending (via eye contact), the experimenter presented one item while stating its name in English (e.g., “This is [name of item].” No response was required of the participants. The experimenter presented the items in random order and with an ITI of 1 s. Training Set 1 was presented in six trial blocks plus four remedial blocks; Training Set 2 was presented in nine trial blocks plus five remedial blocks; and Training Set 3 was presented in six trial blocks plus seven remedial blocks. The number of SPOP and remedial SPOP trial blocks was yoked to that required for participants with similar characteristics to master the same relations in a previous study that employed a different teaching procedure (Rosales, Rehfeldt, & Lovett, 2011). The same presentation of training and remedial trial blocks was followed for all corresponding MET sets. Tokens and praise for compliance with instructions unrelated to the experiment were delivered on a variable-interval (VI) 30-s schedule.

Multiple-exemplar training

All MET sets initially were trained with respect to listener relations in the same manner described above, using SPOP. Next, we conducted tact training in which verbal prompts initially were delivered immediately (for the first three trials) and then faded via prompt delay. The experimenter praised correct responses and delivered model prompts following incorrect responses. The mastery criterion was three consecutive correct unprompted responses for each stimulus in the set. This was followed by one eight-trial block conducted under extinction to expose participants to the contingencies in effect during the remaining posttraining probes, conducted with the original sets. A posttraining probe was conducted following mastery criterion of each corresponding MET set, as depicted in Figures 1 and 2.

Maintenance probes

Maintenance probes, identical to the pre- and posttraining probes, were conducted approximately 1 month after termination of training.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Results for all participants are presented in Figures 1 and 2. During pretraining probes, participants' correct responses ranged from 0% to 13% for tact relations and from 0% to 88% for listener relations (for Cecelia, one listener pretraining probe was at 88% correct, but decreased to 75% correct on a subsequent probe). Pretraining generalization probes ranged from 0% to 50% correct. After the SPOP and remedial SPOP, some participants met mastery criterion for both tact and listener relations on some sets (Sets 1 and 2 for Cecelia, Set 2 for Jason). All participants showed increases in both tact and listener responses for some of the stimulus sets following SPOP. However, MET was implemented for six of the stimulus sets across the three participants. Overall, listener responses were more likely to emerge than tact responses following SPOP. MET was then implemented until the mastery criterion was achieved for the original training sets. One notable exception was Jason's results with Training Set 1, in which he was exposed to three MET sets but never attained mastery criterion for either tact or listener relations. After training, stimulus generalization was evident for some but not all stimulus sets. Specifically, scores ranged from 75% to 100% for Myra; 25% to 75% for Cecelia; and 38% to 100% for Jason. Follow-up probes revealed that listener relations were maintained at a higher percentage than tact relations across all participants.

Results of the present study lend support for the use of a stimulus pairing procedure (Luciano, Gomez-Becerra, & Rodriguez-Valverde, 2007; Smyth et al., 2006) to establish tact and listener relations in typically developing children learning a second language. The study is the first to use SPOP and evaluate maintenance and generalization of established relations. An important avenue for future studies would be to explore the efficacy of SPOP following fewer exposures to each stimulus by conducting posttraining probes after one or two eight-trial blocks (rather than six to nine trial blocks, as occurred in the present study). Alternatively, longer exposures to each stimulus using SPOP alone may lead to mastery in the absence of MET. Future studies might also require a more stringent mastery criterion (i.e., 100% across one trial block) to promote maintenance of tact and listener relations. Finally, the evaluation of potential confounding effects of repeated exposure to testing should be investigated by systematically varying the number of tact and listener pretraining probes across participants instead of stimulus sets.

A limitation of the present investigation is the high level of listener responses during pretraining probes for most stimulus sets. This limits the extent to which we can infer a functional relation between the training procedures and participant performance for listener relations. However, establishment of tact relations was shown clearly for most stimulus sets following either the SPOP alone or a combination of SPOP and MET. Further, it is important to note that the effectiveness of this procedure may require learners to have some prerequisite skills, such as joint attention and covert echoic behavior. With participants who lack these and other important prerequisite skills, SPOP is less likely to be effective. In addition, there is no indication that SPOP is equally or more effective than teaching procedures that require the learner to respond actively. Nevertheless, the investigation of SPOP is an important avenue for research because it closely resembles many naturalistic interactions that occur during typical development. For instance, adults frequently direct children's attention to novel items in the environment while vocalizing the name of the items, but without necessarily requiring a response from the child (Hart & Risley, 1995). Therefore, further research on SPOP might lead to valuable knowledge regarding instructional histories that enable children to acquire novel verbal relations through naturalistic observation of others' behavior.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the Verbal Behavior Special Interest Group, and is based on portions of a dissertation submitted by the first author to fulfill requirements of a doctoral degree from Southern Illinois University. We thank the staff at Southern Seven Headstart for allowing us to conduct this research at their school and Kristin DeFiore for assistance with reliability data.

REFERENCES

- Clayton M.C, Hayes L.J. A comparison of match-to-sample and respondent type training of equivalence classes. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:579–602. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Owens J.C, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer R.D, Stolfi L, Chavez-Brown M, Rivera-Valdes C. The emergence of the listener to speaker component of naming in children as a function of multiple exemplar instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:123–134. doi: 10.1007/BF03393014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley T.R. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore: Brookes; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Leader G, Barnes-Holmes D. Establishing fraction-decimal equivalence using a respondent-type training procedure. The Psychological Record. 2001a;51:151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Leader G, Barnes-Holmes D. Matching to sample and respondent-type training as methods for producing equivalence relations: Isolating the critical variable. The Psychological Record. 2001b;51:429–444. [Google Scholar]

- Leader G, Barnes D, Smeets P.M. Establishing equivalence relations using a respondent type training procedure. The Psychological Record. 1996;46:685–706. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano C, Gomez-Becerra I, Rodriguez-Valverde M. The role of multiple exemplar training and naming in establishing derived equivalence in an infant. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2007;87:349–365. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.08-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales R, Rehfeldt R.A, Lovett S. Effects of multiple exemplar training on the emergence of derived relations in preschool children learning a second language. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2011;27:61–74. doi: 10.1007/BF03393092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth S, Barnes-Holmes D, Forsyth J.P. A derived transfer of simple discrimination and self-reported arousal functions in spider fearful and non-fearful participants. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2006;85:223–246. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.02-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]