Abstract

Populations vary in time and in space, and temporal variation may differ from spatial variation. Yet, in the past half century, field data have confirmed both the temporal and spatial forms of Taylor's power Law, a linear relationship between log(variance) and log(mean) of population size. Recent theory predicted that competitive species interactions should reduce the slope of the temporal version of Taylor's Law. We tested whether this prediction applied to the spatial version of Taylor's Law using simple, well-controlled laboratory populations of two species of bacteria that were cultured either separately or together for 24 h in media of widely varying nutrient richness. Experimentally, the spatial form of Taylor's Law with a slope of 2 held for these simple bacterial communities, but competitive interactions between the two species did not reduce the spatial Taylor's Law slope. These results contribute to the widespread usefulness of Taylor's Law in population ecology, epidemiology and pest control.

Keywords: Taylor's Law, populations, competition, bacteria, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Serratia marcescens

1. Introduction

Starting half a century ago, Taylor et al. [1–4] and nearly a thousand other papers [5] demonstrated a linear relationship (commonly called ‘Taylor's Law’) between the log(variance) of the population size or density of a species and the log(mean) of population size or density. This relationship applies to both spatial and temporal population samples [4]. Numerous mechanisms affecting the slope of this linear relationship have been examined theoretically [6,7–10], but few have been investigated experimentally [11].

Kilpatrick & Ives [10] suggested that interspecific competition might reduce the slope of the temporal form of Taylor's Law, i.e. lower the rate at which log(variance) increases with log(mean) when mean and variance are calculated over time. In a simple dynamic community model, they demonstrated that direct and ‘apparent’ competition could reduce slopes from 2 to a lower value between 1 and 2.

The effect of competition on the spatial form of Taylor's Law has not been investigated either theoretically or empirically. The spatial form of Taylor's Law calculates the mean and the variance of populations sampled (possibly simultaneously) at different points in space, when replicate populations are grouped by some external condition such as available nutrients. We examined experimentally the validity of the spatial form of Taylor's Law and the effect of competition on the slope of Taylor's Law in simple, well-controlled laboratory experiments. We cultured two species of bacteria, both separately and together, in media of widely varying nutrient richness. The bacterial species interacted competitively when they were together, and the spatial form of Taylor's Law usefully described the approximately linear increase of log(variance) with increasing log(mean). The slopes were not significantly different from 2. The presence of a competitor had no statistically significant effect on the slope. On the contrary, the slope was slightly (not statistically significantly) higher in the presence of competition.

2. Material and methods

We used the Gram-negative bacterium Serratia marcescens [12] and a smooth-type stabilized strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 [13]. Each of these two species was cultured alone or in competition with the other (i.e. three types of culture). These cultures were grown in 24 well plates each containing 1.5 ml of King's B (KB) medium (glycerol 10 ml l−1; proteose peptone H3 20 g l−1; dipotassium phosphate K2HPO4 1.5 g l−1; magnesium sulphate MgSO4 1.5 g l−1; distilled water qs 1 l). To create a gradient of environmental richness, we used pure KB medium and KB medium diluted 3, 9, 27, 81, 243, 729 and 2187 times (eight levels). Each of the 3 × 8 = 24 treatments was replicated eight times. We inoculated all the cultures containing P. fluorescens or S. marcescens with bacteria harvested from two diversified mass cultures (one per species). The initial density of bacterial cells was proportional to the richness of the medium used. In pure KB medium, we introduced approximately 3 × 107 P. fluorescens cells, or 3 × 107 S. marcescens cells or 3 × 107 cells of each species into 1.5 ml. Initial densities were thus approximately 2 × 107 colony forming units (CFUs) per millilitre for each species whether alone or in combination. Cultures that contained KB medium diluted three times received one-third of these cell numbers, cultures that contained KB medium diluted nine times received one-ninth of these numbers, etc. All populations were grown at 28°C under constant agitation for 24 h, that is, until they reached carrying capacity. Although we cannot rule out that some evolution occurred in the microcosms, we expect that ecological forces dominated dynamics over the 24-h period (over which a maximum of 10 and seven generations would have occurred in S. marcescens and in P. fluorescens, respectively).

Population densities were then estimated by counting the number of CFUs that appeared after plating 15 µl of (serially diluted) cultures on 1 per cent KB agar. After 24- to 36-h growth, colonies of the two bacterial species were readily recognized and counted under a stereomicroscope based on their colour and morphology. Bacterial density in each culture was estimated by averaging counts from two different 15 µl samples. We calculated the mean and the variance of the population density of each bacterial species over the eight replicates in each of the 24 treatments. After log10 transformation, we obtained 32 points (log(mean), log(variance)): 16 from bacteria grown in monoculture and 16 from bacteria grown with a competitor. Electronic supplementary material, appendix table S1 gives the raw data.

We tested for evidence of competition using ANOVAs, and investigated the effect of competition on the slope of the regression of log(variance) to log(mean) with linear models and ANCOVAs. All statistical computing was performed using R v. 2.9.0 [14].

3. Results

(a). Evidence for competition

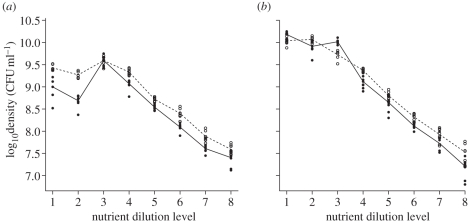

If P. fluorescens and S. marcescens competed for resources, then the presence of each species in a microcosm should reduce the mean population density of the other species. Experimentally, the density of each species was usually lower in the presence of the other species (figure 1). We defined log(mean)competition − log(mean)monoculture as ‘competitive intensity’ and interpreted more negative values of competitive intensity as indicating greater competition. Most values of competitive intensity were negative (figure 1a,b). ANOVAs of competitive intensity rejected the null hypothesis of no competitive effects of S. marcescens and P. fluorescens on each other with high statistical significance (p < 0.001; table 1). In most cases, competitor presence lowered the log10(bacterial concentration) by more than 0.5 units (figure 1), which represents an almost threefold reduction in the absolute number of bacteria. Competition had thus a very strong effect on population density.

Figure 1.

Competition lowers abundance. The effect of competitor presence on bacterial densities (expressed in log10 of CFU ml−1) for (a) P. fluorescens and (b) S. marcescens, by level of KB dilution, between treatments alone and in competition. (a,b) Filled circles with solid line, in competition; open circles with dashed line, alone. Dilution levels 1 through 8 correspond to actual dilutions of 1, 3, 9, 27, 81, 243, 729, and 2187 times, respectively.

Table 1.

Bacterial species compete. Competition, KB dilution and their interaction (competition × KB) affected P. fluorescens and S. marcescens population densities with very high statistical significance, by ANOVA.

| d.f. | sum-squared | mean-squared | F-value | Pr(>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANOVA table for P. fluorescens. Response: log(density) | |||||

| competition | 1 | 5.91 | 5.91 | 75.42 | 3.961e−14*** |

| KB dilution | 7 | 339.45 | 48.49 | 618.75 | <2.2e−16*** |

| competition × KB | 7 | 4.65 | 0.66 | 8.4765 | 2.860e−08*** |

| residuals | 110 | 8.62 | 0.08 | ||

| ANOVA table for S. marcescens. Response: log(density) | |||||

| competition | 1 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 11.807 | 0.000836*** |

| KB dilution | 7 | 625.19 | 89.31 | 1090.763 | <2.2e−16*** |

| competition × KB | 7 | 7.76 | 1.11 | 13.534 | 1.739e−12*** |

| residuals | 109 | 8.93 | 0.08 | ||

***p < 0.001.

We further tested with ANCOVAs whether competitive intensity was strongest when culture medium richness was lowest. We found no statistically significant support for this hypothesis with S. marcescens (F1,6 = 4.86, p = 0.07) or P. fluorescens (p > 0.1; figure 1). Competition was generally less intense at an intermediate KB dilution (electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2), and at some intermediate KB dilutions mean abundance of one bacterial species in the presence of the other exceeded mean abundance in the absence of the other. This U-shaped pattern was more pronounced for P. fluorescens than for S. marcescens. The U-shaped pattern probably occurs because P. fluorescens grows better in slightly diluted KB medium.

(b). Effect of competition on the relation between log(variance) and log(mean)

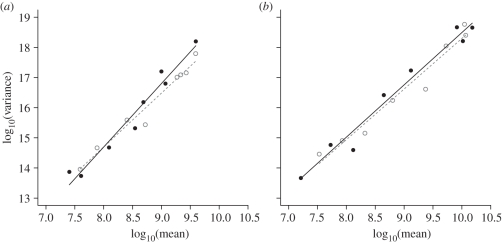

Mean bacterial densities varied by approximately 2.2 orders of magnitude for P. fluorescens (2.5 × 107 − 3.9 × 109 CFU ml−1) and 3.0 orders of magnitude for S. marcescens (1.6 × 107 − 1.5 × 1010 CFU ml−1) across all treatments when pooling all data. The variance of bacterial population densities varied among treatments by approximately 4.5 orders of magnitude for P. fluorescens (5.4 × 1013 − 1.6 × 1018) and 5.1 orders of magnitude for S. marcescens (4.6 × 1013 − 5.8 × 1018). Hence, if the relation between log(variance) and log(mean) were approximately linear, then the slope of log(variance) as a linear function of log(mean) would be expected to be approximately 4.5/2.2 = 2.0 for P. fluorescens and 5.1/3.0 = 1.7 for S. marcescens.

To investigate the effect of competition on the relation between log(variance) and log(mean), we performed linear regressions, for each species separately, of the dependent variable log(variance) on the independent variable log(mean), for the treatments with and without competition. Then, we used ANCOVAs to test for a slope difference. ANCOVAs did not indicate any statistically significant differences in slopes (interactions between log(mean) and the competition term; p > 0.1). For P. fluorescens, the slopes without and with the competitor were 1.784 ± 0.33 (95% confidence interval) and 2.104 ± 0.426, respectively (figure 2a). For S. marcescens, the slopes without and with the competitor were 1.677 ± 0.346 and 1.734 ± 0.304, respectively (figure 2b). Though the slopes are not significantly different from one another, for both species the slope in the presence of the competitor was higher than the slope without the competitor. This finding for the spatial relationship between log(variance) and log(mean) is contrary to the prediction of Kilpatrick & Ives [10] for the temporal version of Taylor's Law.

Figure 2.

Taylor's Law holds. Linear regression of log(variance) to log(mean) of the bacterial densities of (a) P. fluorescens and (b) S. marcescens either grown alone in monoculture or in competition with one another. (a,b) Filled circles with solid line, in competition; open circles with dashed line, alone.

When we fitted P. fluorescens and S. marcescens data together in a single model that contained factors describing whether observations originated from competitive microcosms and the identity of the bacterial species, the interaction between competition and log(mean) was not significant. As in the previous analysis, this analysis provided no evidence that slopes for the spatial form of Taylor's Law were lower in the presence of a competitor (table 2). The terms describing the bacterial species and its interaction with log(mean) were not significant either (p > 0.1).

Table 2.

Competition does not change slopes. Neither competition nor species identity had a statistically significant effect (p > 0.1) on the slope of log(variance) as a function of log(mean), nor were there statistically significant effects on the slope of interactions of log(mean) with competition or interactions of log(mean) with species identity, by ANCOVA.

| d.f. | sum-squared | mean-squared | F-value | Pr(>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOVA table to test for the effect of competition on regressions slopes. Response: log(variance) | |||||

| log(mean) | 1 | 78.626 | 78.626 | 706.1704 | <2e−16*** |

| competition | 1 | 0.186 | 0.186 | 1.6662 | 0.2081 |

| species | 1 | 0.131 | 0.131 | 1.1747 | 0.2884 |

| log(mean) × competition | 1 | 0.096 | 0.096 | 0.8630 | 0.3614 |

| log(mean) × species | 1 | 0.296 | 0.296 | 2.6541 | 0.1153 |

| residuals | 26 | 2.895 | 0.111 | ||

***p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

Theory has identified numerous processes that could influence relationships between log(variance) and log(mean) [4,6,9,10] in population data, but experimental demonstrations of their role have been elusive. We found that the spatial version of Taylor's Law described well the linear increase in log(variance) with increasing log(mean) for each of two bacterial species grown with or without the other. A reduction in mean population size in the presence of the other species demonstrated competition between the bacterial species when they were grown together. The slope of Taylor's Law was not reduced by interspecific competition in our experiments.

These findings suggest that the spatial version of Taylor's Law does not always satisfy the prediction by Kilpatrick & Ives [10] that interspecific competition lowers slopes in the temporal form of Taylor's Law. The confirmation of the spatial form of Taylor's Law and the failure to detect a reduction in slope from values near 2 as a result of competition in these experiments means that an ecological understanding of at least the spatial version of Taylor's Law remains an open challenge. In light of the widespread usefulness of Taylor's Law in areas such as population ecology [15,16], epidemiology [17], and the spatial and temporal dynamics of agricultural pests [18–20], it is a challenge of significance.

Acknowledgements

We thank Anthony Ives and two referees for helpful comments on an earlier version of this study. J.R., S.F. and M.E.H. were supported by grants from the Agence National de la Recherche ‘EvolStress’ (ANR-09-BLAN-099-01) and ‘EvolRange’ (ANR-09-PEXT-011). J.E.C.'s participation in this research was supported by grants DMS-0443803 and EF-1038337 from the US National Science Foundation, a grant from the Region of Languedoc-Roussillon through the University of Montpellier 2, the assistance of Priscilla K. Rogerson and the hospitality of Michael Hochberg and family during this work.

References

- 1.Taylor L. R. 1961. Aggregation, variance and the mean. Nature 189, 732–735 10.1038/189732a0 (doi:10.1038/189732a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor L. R., Woiwod I. P., Perry J. N. 1978. The density-dependence of spatial behaviour and the rarity of randomness. J. Anim. Ecol. 47, 383–406 10.2307/3790 (doi:10.2307/3790) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor L. R., Woiwood I. P. 1980. Temporal stability as a density-dependent species characteristic. J. Anim. Ecol. 49, 209–224 10.2307/4285 (doi:10.2307/4285) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor L. R., Woiwod I. P. 1982. Comparative synoptic dynamics. I. Relationships between interspecific and intraspecific spatial and temporal variance-mean population parameters. J. Anim. Ecol. 51, 879–906 10.2307/4012 (doi:10.2307/4012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisler Z., Bartos I., Kertész J. 2008. Fluctuation scaling in complex systems: Taylor's Law and beyond. Adv. Phys. 57, 89–142 10.1080/00018730801893043 (doi:10.1080/00018730801893043) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson R. M., Gordon D. M., Crawley M. J., Hassell M. P. 1982. Variability in the abundance of animal and plant species. Nature 296, 245–248 10.1038/296245a0 (doi:10.1038/296245a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballantyne F. 2005. The upper limit for the exponent of Taylor's power law is a consequence of deterministic population growth. Evol. Ecol. Res. 7, 1213–1220 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engen S., Lande R., Sæther B. E. 2008. A general model for analyzing Taylor's spatial scaling laws. Ecology 89, 2612–2622 10.1890/07-1529.1 (doi:10.1890/07-1529.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keeling M. J. 2000. Simple stochastic models and their power-law behaviour. Theor. Popul. Biol. 58, 21–31 10.1006/tpbi.2000.1475 (doi:10.1006/tpbi.2000.1475) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilpatrick A. M., Ives A. R. 2003. Species interactions can explain Taylor's power law for ecological time series. Nature 422, 65–68 10.1038/nature01471 (doi:10.1038/nature01471) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benton T. G., Beckerman A. P. 2005. Population dynamics in a noisy world: lessons from a mite experimental system. Adv. Ecol. Res. 37, 143–181 10.1016/S0065-2504(04)37005-4 (doi:10.1016/S0065-2504(04)37005-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hejazi A., Falkiner F. R. 1997. Serratia marcescens J. Med. Microbiol. 46, 903–912 10.1099/00222615-46-11-903 (doi:10.1099/00222615-46-11-903) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rainey P. B., Bailey M. J. 1996. Physical and genetic map of the Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 19, 521–533 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.391926.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.391926.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.R Development Core Team. 2009. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaston K. J., Borges P. A. V., He F., Gaspar C. 2006. Abundance, spatial variance and occupancy: arthropod species distribution in the Azores. J. Anim. Ecol. 75, 646–656 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01085.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01085.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver T., Roy D. B., Hill J. K., Brereton T., Thomas C. D. 2010. Heterogeneous landscapes promote population stability. Ecol. Lett. 13, 473–484 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01441.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01441.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morand S., Krasnov B. R. 2008. Why apply ecological laws to epidemiology? Trends Parasitol. 24, 304–309 10.1016/j.pt.2008.04.003 (doi:10.1016/j.pt.2008.04.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binns M. R., Nyrop J. P., van der Werf W. 2000. Sampling and monitoring in crop protection. Oxon, UK: CABI [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park H., Cho K. 2004. Use of covariates in Taylor's power law for sequential sampling in pest management. J. Agr. Biol. Environ. 9, 462–478 10.1198/108571104X15746 (doi:10.1198/108571104X15746) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young L. J., Young J. H. 1994. 23 Statistics with agricultural pests and environmental impacts. Hand. Stat. Environ. Stat. 12, 735–770 10.1016/S0169-7161(05)80025-2 (doi:10.1016/S0169-7161(05)80025-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]