Abstract

Background

Previous studies have indicated a high prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in women with anorexia nervosa (AN). However, the shared genetic and environmental components of these disorders have not been explored. This study seeks to elucidate the shared genetic and environmental components between GAD and AN.

Method

Using 2,083 women from the Virginia Adult Twin Study of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders, structural equation modeling was used to obtain maximum likelihood estimates of the environmental genetic, shared and unique environmental components in 496 women with GAD, 47 women with AN, 43 women with GAD+AN, and 1,497 women without GAD or AN.

Results

Results show that the heritability of GAD was 0.32 and AN was 0.31, and the genetic correlation between the two disorders was 0.20, indicating a modest genetic contribution to their comorbidity. Unique environment estimate was 0.68 for GAD and 0.69 for AN, with a unique environmental correlation of 0.18. All common environmental parameters were estimated at zero.

Conclusions

The modest shared genetic and unique environmental liability to both disorders may help explain the high prevalence of GAD in women with AN. This knowledge could help in the treatment and prevention of comorbid disorders.

Keywords: anxiety, eating disorders, Cholesky, twin, heritability

INTRODUCTION

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and anorexia nervosa (AN) are significant psychological disorders that share certain features and are frequently comorbid. The comorbidity between anxiety and anxiety disorders, in general, and AN has been well established.[ 1–5] Specifically, comorbidity estimates for GAD and AN have suggested up to 40% of women with AN also have a lifetime history of GAD.[1] Women with AN were more than six times more likely than women without AN to have GAD[4,6] and, conversely, women with GAD were approximately six times more likely to have AN than women without GAD.[6] Anxiety disorders tend to predate the development of AN,[2,5,7] making it likely that GAD would precede AN and biologically plausible that GAD and AN share some genetic factors.

Two potential hypotheses to explain the relationship between these disorders are as follows: (1) there is a common etiologic factor between GAD and AN or (2) there is a phenotypic causal relationship between GAD and AN. If there is a common etiologic factor between GAD and AN, we would expect to see random onset of GAD and AN, mainly AN would not tend to come after GAD or GAD would not tend to come after AN. Given GAD tends to onset before AN[2,5,7] and heritability estimates and prevalence estimates differ substantially, it seems more likely that there is a phenotypic causal relationship between GAD and AN, evidenced by certain phenotypic commonalities.

The notion that GAD and AN share core genetic or environmental factors are supported by phenotypic similarities between the two disorders. Along with high comorbidity, the notion that GAD and AN share some common factors is supported by similar characteristics shared by women with GAD and AN. For example, it has been hypothesized that caloric restriction[6,8,9] and exercise[10,11] are anxiolytic for some individuals. Within women with AN, a relationship between high childhood anxiety and low body mass index (BMI) in the context of AN was mediated through caloric restriction.[9] Higher anxiety was also noted in women with AN who were deemed “excessive exercisers.”[12] If caloric restriction and excessive exercise are anxiolytic for a subgroup of individuals, it is biologically plausible that this hypothesis would extend to others who exhibit anxiety. This is supported by one study which showed women with GAD and no AN were more likely to engage in fasting and excessive exercise than women without GAD and without AN.[6] Since women with both disorder engage in similar behaviors, but to different extents, it is likely that the two disorders share some genetic and environmental features.

The prevalence of GAD and AN differ substantially; full Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) GAD affects approximately 4.1% of individuals,[ 13] using 1-month GAD criteria prevalence is estimated at 7.5% of individuals,[14] and AN affects less than 1% of the population lifetime.[15] However, both disorders tend to show higher prevalence in females,[13,15,16] are associated with high suicidality,[17,18] and tend to aggregate in families.[19,20] Heritability estimates indicated that GAD may have a similar or smaller genetic component than AN. Twin studies have shown heritability estimates ranging from 0.22 to 0.37 for GAD[19,21,22] and from 0.22 to more than 0.70 for AN.[23–25]

Despite the high comorbidity and phenotypic similarities between GAD and AN, thus far few twin studies have explored the shared genetic and environmental components of anxiety and eating disorders. Results of one study indicate that there may be common genetic factors in the development of over-anxious disorder, separation anxiety disorder, depression, and eating disorders.[26] Results of a separate study suggested a common genetic factor for phobias, panic disorder, and bulimia nervosa could exist.[27] In another approach, using only monozygotic (MZ) twins discordant for any eating disorder, results showed possible shared transmission of anxiety and eating disorders.[28] Despite the high comorbidity between GAD and AN, to the best of the authors’ knowledge no studies have specifically examined shared genetic and environmental factors between GAD and AN. Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine the magnitude of shared genetic and environmental components between these disorders. Identifying shared components of GAD and AN could provide additional information about the nature of the comorbidity between these disorders. This information could be helpful in the prevention and treatment of GAD and AN alone and comorbid with one another.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

Participants for this study were a subset from the Virginia Adult Twin Study of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders, described earlier.[29,30] Briefly, this study consisted of 2,163 individuals from female–female twin pairs who completed the Stress and Coping Virginia Twin Project interview in person (89%) or by telephone (11%), had a nonmissing GAD or AN diagnosis, and were classified as MZ or dizygotic (DZ) twins. This yielded a final sample of 2,083 women (99% of the original sample).

ZYGOSITY DETERMINATION

Zygosity determination was based on standard questions regarding how alike the twins were as children,[31] photographs of the twins, and DNA samples.[32] This methodology has previously been described.[30]

MEASURES

Anorexia nervosa-like syndrome

Participants were asked several questions concerning eating habits, including: (1) Have you ever had a time in your life where you weighed much less than other people thought you ought to weigh?; (2) At that time, were you very afraid that you could become fat?; and (3) At your lowest weight, how did you think you looked? Did you still feel that you were too fat or that part of your body was too fat? Participants had to have answered “yes” to the first question to be asked the second and third questions and had to have answered “yes” to all three questions to be considered to have AN. These questions roughly map onto the DSM-IIIR diagnostic criteria for AN.[33] There were 90 women (4.3%) meeting this diagnosis.

Although these criteria for AN are not ideal, they are supported for several reasons. First, to compensate for the low prevalence of AN, the diagnostic criteria often need to be modified for research purposes.[23] Second, throughout the history of DSM, the diagnostic criteria for AN have changed substantially. For example, criterion A for AN has changed from substantial weight loss amounting to 25% of body weight[34] to 85% of ideal body weight;[33] changes to this criterion are currently being debated in DSM-V. Criteria B and C have also undergone changes and additional changes are expected in DSM-V. Third, many similarities have been shown between individuals meeting and not meeting full diagnostic criteria for AN. For example, individuals meeting and not meeting the weight criterion (criterion A) have been shown to be quite similar,[35] so we allowed question 1 to serve as a proxy for underweight. Criterion D (amenorrhea) was not required; it has been previously shown that women meeting and not meeting criterion D are similar, and criterion D is frequently excluded as a requirement for inclusion in research studies.[23] Fourth, criteria used in this study are considered to include individuals with definite, possible, or probable AN,[4] and are more inclusive than many criteria used for AN.[24,28,36,37]

Generalized anxiety disorder

As described in previously,[ 29] GAD was considered present if women met an adapted version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IIIR.[38] The 1-month criteria previously described[29] was used for this study since there are strong similarities between individuals meeting the 1-month and 6-month GAD criteria.[14,29,39] In these samples, 539 women (25.8%) met criterion for GAD.

Statistical methods

Mean [standard deviations (SD)] were calculated for age. Logistic regression analyses were used to compute odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of having AN if GAD was present or having GAD if AN was present. Generalized estimating equation corrections were applied to account for the nonindependence of the data due to the inclusion of cotwins.

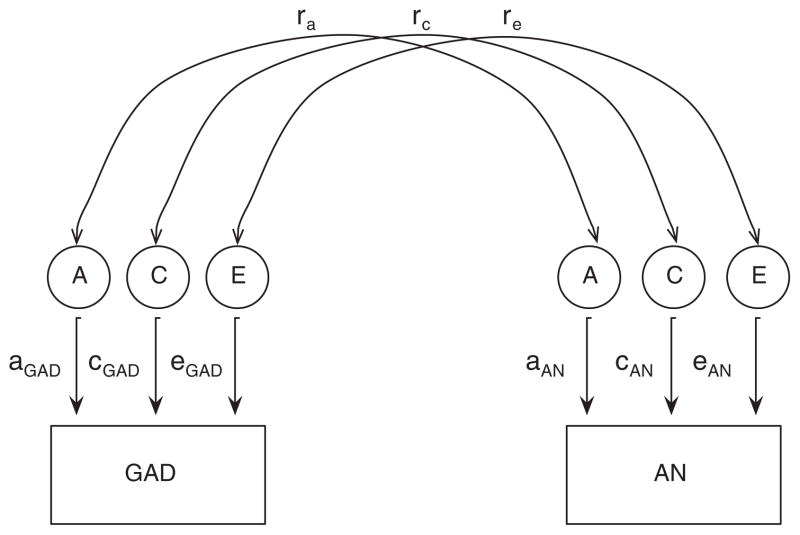

Biometrical twin modeling was conducted in OpenMx using the basic tenets of twin modeling. MZ twins share all genetic material (a2) and DZ twins share roughly half of the genetic material, common environmental factors (c2; e.g., going on vacation with parents as a child) are shared equally by MZ and DZ twins, and unique environmental factors (e2; e.g., going to different colleges) are not shared by MZ or DZ twins; error is included with the e2 parameter. Different patterns of twin resemblance are predicted by the parameters of the genetic model.[40,41] A Cholesky Decomposition was used to estimate the unique and shared genetic, common environmental, and unique components of GAD and AN (Fig. 1). This model contains direct paths from the first genetic, common environmental, and unique environmental factors to the first phenotype and cross paths to the second phenotype. The second genetic, common environmental, and unique environmental factors contain paths only to the second phenotype. This allows for the estimation of the unique and shared parameters. Since GAD tends to predate AN, GAD was entered into the model first followed by AN. Several submodels were then fit to determine whether an equally fitting, more parsimonious model exited.

Figure 1.

Bivariate model for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and anorexia nervosa (AN). A, heritability component; C, common environment component; E, unique environment component; ra, GAD/AN genetic correlation; rc, GAD/AN shared environmental correlation; re, GAD/AN unique environmental/error.

Next, a common factor model was fit to provide better understanding of the relationship between GAD and AN constructs. In this model, we estimated how strongly GAD and each of the AN constructs loaded on a single common factor.

Raw data were analyzed directly using full information maximum likelihood. This methodology eliminates the need for two-stage estimation procedures and is a convenient way to handle missing data.[41] All statistical analyses were conducted in the R software version 2.12.0;[42] all twin modeling was conducted using OpenMx version 1.0.3.[43] The 95% confidence intervals for odds ratios were based on standard errors, whereas those for biometrical twin modeling were based on maximum likelihood estimates.[44]

RESULTS

The mean age of the sample was 29.6 (7.6), the mean age of women in each group were as follows: GAD only (n = 496; 23.8%) 31.5 (7.6), AN only (n = 47; 2.3%) 25.9 (5.7), GAD+AN (n = 43; 2.0%) 27.7 (6.1), and no GAD or AN (n = 1,497; 71.9%) 29.1 (7.5). In this sample, 8% of women with GAD had AN, and conversely 48% of the women with AN had GAD. The odds ratio of having AN if GAD was present was 1.8 (95% confidence interval 1.2–2.8; P < 0.01), and conversely the odds of having GAD if AN was present was 1.8 (95% confidence interval 1.2–2.8; P < 0.01).

Fit statistics for biometrical modeling are contained in Table 1. Given we had low statistical power to distinguish between models and that the C parameters in the full ACE model were estimated at approximately zero, results discussed are for the AE model with correlation of both genetic and unique environmental parameters. Parameter estimates for all models tested are shown in Table 2. For the AE model, heritability estimate for GAD was 0.32 and AN was 0.31. Estimates indicate that the genetic correlation between GAD and AN was 0.20 and the environmental correlation was 0.18. It should be noted that the confidence intervals for the shared correlation between GAD and AN were wide and crossed zero. The best-fit submodel had more narrow confidence intervals for this parameter and did not cross zero, indicating this parameter may be important.

TABLE 1.

Fit statistics for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and anorexia nervosa (AN) Cholesky decomposition

| Model | df | −2LL | Δχ2 | Δdf | P | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE-ACE, ra rc re | 2,826 | 2900.9 | n/a | n/a | n/a | −2,751.1 |

| AE-AE, ra re | 2,829 | 2900.9 | 0 | 3 | 1.00 | −2,757.1 |

| AE-AE, ra* | 2,830 | 2902.2 | 1.3 | 4 | 0.86 | −2,757.8 |

| AE-AE | 2,831 | 2907.4 | 6.5 | 5 | 0.26 | −2,754.6 |

AIC, Akaike information Criterion; Δdf and Δχ2 calculated from full model; n/a, not applicable; A, heritability component; C, common environment component; E, unique environment component; ra, GAD/AN genetic correlation; rc, GAD/AN shared environmental correlation; re, GAD/AN unique environmental/error;

indicates best fit.

TABLE 2.

Parameter estimates for Cholesky decomposition for generalized anxiety disorder and anorexia nervosa

| Model | Variable | a2 | c2 | e2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE-ACE, ra rc re | Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.32 (0.00–0.44) | 0.00 (0.00–0.26) | 0.68 (0.56–0.81) |

| Anorexia nervosa | 0.31 (0.00–0.69) | 0.00 (0.00–0.51) | 0.69 (0.31–1.00) | |

| Shared components | 0.20 (−1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (−1.00–1.00) | 0.18 (−10.13–0.49) | |

| AE-AE, ra re | Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.32 (0.19–0.44 ) | 0.00 | 0.68 (0.56–0.81) |

| Anorexia nervosa | 0.31 (0.00–0.69) | 0.00 | 0.69 (0.31–1.00) | |

| Shared components | 0.20 (−11.00–1.00) | 0.00 | 0.18 (−10.13–0.49) | |

| AE-AE, ra* | Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.32 (0.19–0.45) | 0.00 | 0.68 (0.56–0.81) |

| Anorexia nervosa | 0.32 (0.01–0.70) | 0.00 | 0.68 (0.30–0.99) | |

| Shared components | 0.44 (0.06–1.00) | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| AE-AE | Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.32 (0.19–0.45) | 0.00 | 0.68 (0.56–0.81) |

| Anorexia nervosa | 0.34 (0.00–0.71) | 0.00 | 0.66 (0.30–1.00) | |

| Shared components | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

a2, heritability component; c2, common environment component; e2, unique environment component;

, best fit model.

Results of the common factor model are in accord with results of the Cholesky decomposition. There, results indicate that the three AN constructs measured load heavily onto a common factor. GAD also shows some loading onto this factor, but to a lesser degree than the AN constructs. The factor loading for GAD was 0.25 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Common factor estimates of generalized anxiety disorder and anorexia nervosa constructs

| Variable | Factor loading |

|---|---|

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.25 |

| “Have you ever had a time in your life where you weighed much less than other people thought you ought to weigh?” | 0.91 |

| “At that time, were you very afraid that you could become fat?” | 0.92 |

| “At your lowest weight, how did you think you looked? Did you still feel that you were too fat or that part of your body was too fat?” | 1.00 |

DISCUSSION

Results of this study showed heritability point estimates in the range of univariate analyses for both GAD and AN,[19,21–24] and augment previous literature by indicating that GAD and AN share modest genetic and unique environmental liability. In this study, the shared environmental components were estimated at zero for GAD and AN. There are several potential explanations of these findings.

First, although low BMI is characteristic of AN, it is not always characteristic of GAD. Although some studies have shown an inverse relation between GAD and overweight,[45] other studies showed that individuals with GAD were more likely to be overweight than normal weight.[46] Furthermore, individuals with GAD had lower adult lowest BMIs and higher adult (nonpregnancy) highest BMIs than women without an anxiety disorder.[6] This could indicate that individuals with GAD are a quite heterogenous group. If this is the case, the form of GAD that manifests with low BMI and weight loss behaviors may represent the minority of those with GAD and be overrepresented among individuals with AN. Therefore, it is possible that the shared genetic and unique environmental components between GAD and AN in epidemiological samples would be moderate, but quite large if studying the subgroup of individuals with GAD who have low BMIs and AN-like behaviors.

Second, this study differs from at least one other, in that individuals with anxiety disorders other than GAD without also having GAD could have been included in each group.[6] Therefore, individuals with AN and another anxiety disorder would have been included in the group of individuals with just AN and individuals with no AN and an anxiety disorder other than GAD would have been included in the group of individuals with no disorder. Given the known phenotypic and genetic overlap between anxiety disorders, inclusion of these individuals could have confounded results and might result in smaller estimates of shared genetic and unique environmental liability between disorders. Since previous studies indicated that approximately 83% of individuals with AN had an anxiety disorder at some point in their life and that not all of these individuals have GAD specifically,[2] it is likely that anxiety, in general, shares liability with AN and perhaps not GAD specifically.

Third, although both the genetic and environmental shared liabilities were modest, overall results suggest that GAD and AN share an appreciable percentage of liability. In fact, in the best fit model, genetic liability was estimated at 0.44. The genetic liability between GAD and AN could be quite significant and may help explain why so many individuals with AN have GAD. The unique environmental overlap could suggest that certain environments are more conducive to the development of both disorders; however, it is possible that individuals with comorbid disorders are more likely to seek out this sort of environment than other individuals. Given that a much smaller percentage of individuals with GAD exhibit AN, it is not surprising that there is not more overlap between genes. In addition, it is possible that a higher degree of genetic overlap may occur between symptoms the two disorders share.

Fourth, it is possible that the Cholesky decomposition was not the most appropriate model to study this relationship. Neale and Kendler describe 12 different comorbidity models.[47] Since there is considerably high comorbidity between GAD and AN and the tendency for anxiety to precede the development of AN, it is possible the GAD causes AN model to may have been a better fit. High prevalence of fasting and excessive exercise noted in both GAD and AN[6] could also indicate that these are two forms of the same disorder and an alternate forms model could have been a better fit. The high comorbidity between the disorders could indicate the random or extreme multiformity models would be most appropriate. However, due to the low prevalence of AN, we did not have statistical power to fit these models.

LIMITATIONS

The results of this study must be viewed with caution because of study limitations. First, although diagnoses were similar to DSM-IIIR, the criteria used might not have been precise enough to obtain clinical diagnoses of GAD or AN. Second, individuals who participated in this study might be inherently different from individuals who chose not to participate. For example, this study consisted of primarily Caucasian women and only twins were included. Third, results of this study may not generalize past female twins born between 1934 and 1971 in mid-Atlantic states. Fourth, the study was underpowered, and as a result, confidence intervals for AN and shared genetic correlation between GAD and AN were quite large. Confidence intervals of this size are not uncommon for studies of AN.[23,48] The prevalence of these disorders was also higher than seen in some other epidemiologic samples, but this study used clinically trained interviewers to arrive at diagnosis. It is likely that these diagnoses were more accurate than epidemiological self-report data and unlikely that these disorders were overdiagnosed. Fifth, we did not have information on caloric restriction and exercise, so could not confirm that individuals with GAD in this sample are more likely to engage in those behaviors than women with no disorder nor could we evaluate genetic correlation at the behavioral or symptom level. Sixth, we do not have interrater reliability measures for these data.

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that GAD and AN share a modest portion of genetic and unique environmental liability and these seem responsible for the comorbidity between GAD and AN.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Dellava was supported by NIMH T32MH20030 (PI: MCN). Linda Corey, Ph.D., provided assistance with the ascertainment of twins from the Virginia Twin Registry, now part of the Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry (MATR). The MATR, now directed by Judy Silberg Ph.D., has received support from the NIH, the Carman Trust, and the W.M. Keck, John Templeton, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundations. We thank all participants who made this research possible.

Footnotes

The authors disclose the following financial relationships within the past 3 years: Contract grant sponsor: National Institute of Health (NIH); Contract grant numbers: MH-068643; MH-49492; Contract grant sponsor: NIMH; Contract grant number: T32MH20030; Contract grant sponsor: The Carman Trust, and the W.M. Keck, John Templeton, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundations.

References

- 1.Godart NT, Flament MF, Curt F, et al. Anxiety disorders in subjects seeking treatment for eating disorders: a DSM-IV controlled study. Psychiatry Res. 2003;117:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godart NT, Flament MF, Lecrubier Y, Jeammet P. Anxiety disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: co-morbidity and chronology of appearance. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15:38–45. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godart N, Flament M, Perdereau F, Jeammet P. Comorbidity between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:253–270. doi: 10.1002/eat.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walters EE, Kendler KS. Anorexia nervosa and anorexic-like syndromes in a population-based female twin sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:64–71. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaye WH, Bulik CM, Thornton L, et al. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2215–2221. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thornton LM, Dellava JE, Root TL, et al. Anorexia nervosa and generalized anxiety disorder: further explorations of the relation between anxiety and body mass index. J Anxiety Disord. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raney TJ, Thornton LM, Berrettini W, et al. Influence of overanxious disorder of childhood on the expression of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:326–332. doi: 10.1002/eat.20508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaye WH, Fudge JL, Paulus M. New insights into symptoms and neurocircuit function of anorexia nervosa. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrn2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dellava JE, Thornton LM, Hamer RM, et al. Childhood anxiety associated with low BMI in women with anorexia nervosa. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norris R, Carroll D, Cochrane R. The effects of physical activity and exercise training on psychological stress and well-being in an adolescent population. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:55–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90114-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sexton H, Maere A, Dahl NH. Exercise intensity and reduction in neurotic symptoms. A controlled follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;80:231–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb01332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shroff H, Reba L, Thornton LM, et al. Features associated with excessive exercise in women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39:454–461. doi: 10.1002/eat.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, et al. Prevalence, correlates, co-morbidity, and comparative disability of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the USA: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1747–1759. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, Tsang A, Ruscio AM, et al. Implications of modifying the duration requirement of generalized anxiety disorder in developed and developing countries. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1163–1176. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, et al. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan PF. Mortality in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1073–1074. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cougle JR, Keough ME, Riccardi CJ, Sachs-Ericsson N. Anxiety disorders and suicidality in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:825–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hettema J, Neale M, Kendler K. Physical similarity and the equal-environment assumption in twin studies of psychiatric disorders. Behav Genet. 1995;25:327–335. doi: 10.1007/BF02197281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strober M, Freeman R, Lampert C, et al. Controlled family study of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: evidence of shared liability and transmission of partial syndromes. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:393–401. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. A population-based twin study of generalized anxiety disorder in men and women. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:413–420. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scherrer JF, True WR, Xian H, et al. Evidence for genetic influences common and specific to symptoms of generalized anxiety and panic. J Affect Disord. 2000;57:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellava JE, Thornton LM, Lichtenstein P, et al. Impact of broadening definitions of anorexia nervosa on sample characteristics. J Psychiatr Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klump KL, Miller KB, Keel PK, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on anorexia nervosa syndromes in a population-based twin sample. Psychol Med. 2001;31:737–740. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazzeo SE, Mitchell KS, Bulik CM, et al. Assessing the heritability of anorexia nervosa symptoms using a marginal maximal likelihood approach. Psychol Med. 2009;39:463–473. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silberg J, Bulik C. Developmental association between eating disorders symptoms and symptoms of anxiety and depression in juvenile twin girls. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:1317–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kendler KS, Walters EE, Neale MC, et al. The structure of the genetic and environmental risk factors for six major psychiatric disorders in women: phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, bulimia, major depression and alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:374–383. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950170048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keel P, Klump K, Miller K, et al. Shared transmission of eating disorders and anxiety disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38:99–105. doi: 10.1002/eat.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, et al. Generalized anxiety disorder in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:267–272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820040019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, et al. A population-based twin study of major depression in women: the impact of varying definitions of illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:257–266. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820040009001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eaves LJ, Eysenck HJ, Martin NG. Genes, Culture and Personality: An Empirical Approach. London: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spence JE, Corey LA, Nance WE, et al. Molecular analysis of twin zygosity using VNTR DNA probes. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;43:A159. [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. III-R. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas JJ, Vartanian LR, Brownell KD. The relationship between eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) and officially recognized eating disorders: meta-analysis and implications for DSM. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:407–433. doi: 10.1037/a0015326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kortegaard LS, Hoerder K, Joergensen J, et al. A preliminary population-based twin study of self-reported eating disorder. Psychol Med. 2001;31:361–365. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanci L, Coffey C, Olsson C, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and eating disorders in females: findings from the Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:261–267. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M, First M. Biometrics Research Department. New York: State Psychiatric Institute; 1988. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R: Patient Version (SCID-P, 4/1/88) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breslau N, Davis GC. DSM-III generalized anxiety disorder: an empirical investigation of more stringent criteria. Psychiatry Res. 1985;15:231–238. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(85)90080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neale M, Maes H. Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. B.V; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neale M, Cardon L. Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. B.V; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 42.R Development Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Version 2.11.1. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boker S, Neale MC, Maes HH, et al. OpenMx: an open source extended structural equation modeling framework. Psychometrika. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11336-010-9200-6. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neale MC, Miller MB. The use of likelihood-based confidence intervals in genetic models. Behav Genet. 1997;27:113–120. doi: 10.1023/a:1025681223921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasler G, Pine DS, Gamma A, et al. The associations between psychopathology and being overweight: a 20-year prospective study. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1047–1057. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petry NM, Barry D, Pietrzak RH, Wagner JA. Overweight and obesity are associated with psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:288–297. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181651651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neale M, Kendler K. Models of comorbidity for multifactorial disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:935–953. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bulik CM, Thornton LM, Root TL, et al. Understanding the relation between anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in a Swedish national twin sample. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]