Invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella Typhimurium disease is a common and frequently recurrent cause of bacteremia across sub-Saharan Africa. We use high-resolution single nucleotide polymorphism analysis to distinguish between reinfection and recrudescence in disease recurrence within single individuals over time.

Abstract

Background. Bloodstream infection with invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella (iNTS) is common and severe among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected adults throughout sub-Saharan Africa. The epidemiology of iNTS is poorly understood. Survivors frequently experience multiply recurrent iNTS disease, despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy, but recrudescence and reinfection have previously been difficult to distinguish.

Methods. We used high-resolution single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) typing and whole-genome phylogenetics to investigate 47 iNTS isolates from 14 patients with multiple recurrences following an index presentation with iNTS disease in Blantyre, Malawi. We isolated nontyphoidal salmonellae organisms from blood (n = 35), bone marrow (n = 8), stool (n = 2), urine (n = 1), and throat (n = 1) samples; these isolates comprised serotypes Typhimurium (n = 43) and Enteritidis (n = 4).

Results. Recrudescence with identical or highly phylogenetically related isolates accounted for 78% of recurrences, and reinfection with phylogenetically distinct isolates accounted for 22% of recurrences. Both recrudescence and reinfection could occur in the same individual, and reinfection could either precede or follow recrudescence. The number of days to recurrence (23–486 d) was not different for recrudescence or reinfection. The number of days to recrudescence was unrelated to the number of SNPs accumulated by recrudescent organisms, suggesting that there was little genetic change during persistence in the host, despite exposure to multiple courses of antibiotics. Of Salmonella Typhimurium isolates, 42 of 43 were pathovar ST313.

Conclusions. High-resolution whole-genome phylogenetics successfully discriminated recrudescent iNTS from reinfection, despite a high level of clonality within and among individuals, giving insights into pathogenesis and management. These methods also have adequate resolution to investigate the epidemiology and transmission of this important African pathogen.

Nontyphoidal salmonellae (NTS) are among the commonest causes of invasive bacterial disease across sub-Saharan Africa [1–4]. Invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella (iNTS) disease predominantly affects children with malnutrition, malaria, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [1], and HIV-infected adults, among whom the condition frequently recurs [3]. Case-fatality rates are high in both adults (22%–47%) and children (21%–24%), despite therapeutic intervention [3–5]. The epidemiology and transmission of iNTS are poorly understood.

In HIV-infected adults who are not treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART), iNTS disease is frequently recurrent, with recurrence in 20%–43% of index cases. Of these casess, ≤25% have multiple recurrences [3]. Recurrent iNTS disease following a course of appropriate antimicrobials has been attributed to both recrudescence of the same organism and reinfection with a distinctly different strain [3, 6, 7]. Previous analyses of paired isolates from index presentation and recurrence events using serology, antibiotic-resistance profiling, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and plasmid profiling identified recrudescence as the most likely driver of recurrent disease in Malawian HIV-infected patients [3]. These subgenomic methods, however, lack the resolution to definitively discriminate between recrudescence and reinfection [6, 8].

We therefore used high-quality, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based, phylogenetic analyses based on whole-genome sequences to detect phylogenetic differences between index and recurrent isolates at very high resolution. Recently, SNP-based typing methods have been used to demonstrate the genetic variation between very closely related bacterial strains in clinically important settings [9, 10]. We demonstrate here the value of whole-genome phylogenetic methods in resolving variation between African iNTS isolates, to understand pathogenesis and guide effective therapeutic and preventive measures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and Isolates

The isolates and clinical events described here arose from a larger study in which consecutive febrile adult (>14 y) patients in Blantyre were recruited. Patients with iNTS were identified at an index event by blood and bone-marrow culture, treated with ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice per day for 10–14 days, and followed up monthly to detect recurrence of invasive disease [11]. Recurrent episodes of invasive iNTS disease were retreated with ciprofloxacin. All iNTS patients were HIV-infected.

At follow-up, we collected blood samples, and we requested bone-marrow sampling, for culture, when there was a febrile episode. Simultaneous mucosal samples (urine, stool, throat swab) were also taken when possible. We used previously described diagnostic microbiological methods [11]. We isolated NTS from blood or bone-marrow samples by automated culture (BacT/Alert 3D, BioMérieux) or pour-plate culture in Columbia agar. Stool, urine, and throat swabs were cultured in selenite broth and subcultured onto xylose–lysine–deoxycholate agar. We used standard biochemical and serological methods to identify NTS, which were then stored at –80°C. Series of all Salmonella isolates from 14 individuals who had multiple recurrences of iNTS disease were selected for genomic analysis.

Genomic DNA Preparation

Bacteria were grown on Luria–Bertani (LB) medium then incubated in LB broth overnight at 37°C. We pelleted bacterial cells by centrifugation and extracted DNA using the Wizard Genomic DNA kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We checked DNA quality and quantity by gel electrophoresis and Qubit quantitation platform (Invitogen). We submitted 20–50 ng/μL of DNA from each isolate for Illumina sequencing.

Library Preparation and DNA Sequencing

We prepared multiplex libraries with 54 or 76 base-pair (bp) reads and 200 bp insert sizes [9]. We conducted cluster formation, primer hybridization, and sequencing reactions using the Illumina Genome Analyzer System [12] according to standard protocols [9]. An average of 97.3% of the reference was mapped with a mean depth of 53.3-fold in mapped regions across all isolates (Supplementary Table 1). We submitted the sequence data to the European Nucleotide Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena).

SNP Detection and Phylogenetic Analyses

We mapped the sequence data from each isolate to the nonrepetitive genome sequence of the reference SL1344, which was obtained by excluding phage sequences and exact repetitive sequences of ≥20 bp identified using the repeat-finding programs nucmer, REPeuter, and repeat-match [13–16]. We mapped reads from each isolate onto the reference genome using SSAHA v2.2.1 [17] with a minimum mapping score of 30. We identified SNPs using SSAHA_pileup and filtered them with a minimum mapping quality of 30 and a SNP/mapping quality ratio cutoff of 0.75 [9, 14]. A total of 45 497 chromosomal sites contained a high-quality SNP in at least 1 mapped isolate. We constructed maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees with RAxML v7.0.4 [18] with alignment of all the concatenated 45 497 variant sites from each of the isolates. We removed from the alignment 4 isolates with >12 000 SNP differences from the reference, as these were unlikely to be Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Salmonella Typhimurium), and recalculated the maximum-likelihood tree using 51 isolates with 1463 SNP sites. In both calculations, we used the general time-reversible model with a gamma correction for site variation as the nucleotide substitution model. We calculated likelihood test ratios as previously described [9]. We checked support for nodes on the trees using 100 random bootstrap replicates.

Validation of Phylogenetic Clusters

We used several independent approaches to validate the phylogenetic tree. Concatenated SNP alignments generated for 51 isolates consisting of 1463 chromosomal SNP loci were used to construct additional unrooted phylogenetic trees, via neighbor joining and maximum-parsimony methods with the PHYLIP 3.69 package [19]. We evaluated the support for the nodes of the resultant tree clusters by bootstrap analyses based on 100 replicates. We conducted a Bayesian phylogenetic analysis using MrBayes 3.1 [20, 21]. We used a general time-reversible substitution model with gamma rate variation. The Markov chain Monte Carlo method ran until it reached convergence for 1 000 000 generations and sample frequency of 100. Summaries were based on 15 002 samples from 2 runs. Each run produced 10 001 trees, of which 7501 were included. We used 15 002 final trees for posterior probability distribution calculations; the probability of each partition or clade on resulting tree was given as a credibility value. To find the best clustering of isolatese, we used the Bayesian Analysis of Population Structure (BAPS) 5 package [22] to further probe the population structure using Bayesian statistical approaches. We performed a genetic-mixture analysis for each concatenated SNP sequence and the dependencies present between loci within the aligned sequences [23]. We conducted sequential clustering analyses on identified clusters until single-member clusters were obtained [22, 23].

Phylogenetic Relationships of Non-iNTS Typhimurium Isolates

We calculated a separate maximum-likelihood tree including the 4 isolates that had SNP differences of >12 000 from the Salmonella Typhimurium SL1344 reference, and 11 additional reference Salmonella enterica serovars including Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis, Salmonella Typhi, and Salmonella Paratyphi groups A, B, and C (Supplementary Table 2).

Discrimination Between Recrudescent and Reinfection Isolates

We based classification of recrudescent and reinfection isolates primarily on their relationship within the phylogenetic trees by determining whether 1 isolate could have been plausibly derived from another with reference to the structure. We calculated the number of pairwise SNP differences between index and recurrence isolates.

RESULTS

SNP and Phylogenetic Analyses of Recurrent iNTS Disease Isolates Based on Whole-Genome Sequences

We selected 47 index and recurrence NTS isolates from systemic and mucosal sites, from 14 patients who had multiple recurrences following an index presentation with iNTS. Sampling at different sites is described in Table 1. The isolates used are summarized in Table 2; they comprised 35 blood isolates, 8 bone-marrow isolates, 2 stool isolates, and a single isolate each from an oral-pharyngeal swab and a urine sample. To control the study, we also included 7 previously sequenced Malawian iNTS Typhimurium isolated from blood cultures of febrile pediatric hospital admissions and the gastroenteritis-associated reference SL1344 [24].

Table 1.

Sampling and Isolation of Nontyphoidal Salmonellae From Cohort

| By Patient (n = 14) |

By Event (n = 71) |

|||||

| Site Sampled | No. of Patients Sampled | No. of Patients Positive for NTS | Patients Positive for NTS, % | No. of Events Sampled | No. of Events Positive for NTS | Events Positive for NTS, % |

| Blood | 14 | 13 | 93 | 71 | 32 | 45 |

| Bone marrow | 12 | 9 | 75 | 22 | 11 | 50 |

| Stool | 7 | 2 | 29 | 15 | 4 | 27 |

| Urine | 14 | 3 | 21 | 35 | 3 | 8 |

Abbreviations: NTS, nontyphoidal salmonellae.

Table 2.

Isolates Used in the Studya

| Index Isolate | Date of Isolation | Recurrent Isolate 1 | Date of Isolation | Recurrent Isolate 2 | Date of Isolation | Recurrent Isolate 3 | Date of Isolation | Recurrent Isolate 4 | Date of Isolation |

| Q18A | 28/03/2002 | Q18A_S | 28/03/2002 | Q18F2 | 24/05/2002 | Q18F3_S | 22/06/2002 | ||

| Q23A | 26/02/2002 | Q23F1 | 25/03/2002 | Q23F2_BM | 26/04/2002 | Q23F5 | 26/03/2003 | ||

| Q134A | 30/05/2002 | Q134F4 | 16/10/2002 | Q134F8 | 28/04/2003 | Q134F9 | 06/09/2003 | ||

| Q175A | 01/07/2002 | Q175F4_TH | 27/01/2003 | Q175F6 | 07/04/2003 | ||||

| Q213F1a | 02/09/2002 | Q213F1b | 05/09/2002 | Q213F3_BM | 21/10/2002 | ||||

| Q217A | 18/03/2002 | Q217F3 | 12/11/2002 | ||||||

| Q255A | 17/09/2002 | Q255F1_BM | 10/10/2002 | Q255F2_U | 13/11/2002 | Q255F4 | 26/03/2003 | ||

| Q258A | 21/10/2002 | Q258F3_BM | 07/01/2003 | Q258F4 | 02/03/2003 | ||||

| Q285A | 22/08/2002 | Q285F1_BM | 11/11/2002 | Q285F5 | 22/04/2003 | ||||

| Q303A | 26/11/2002 | Q303F1 | 20/12/2002 | Q303F3 | 02/03/2003 | Q303F5 | 22/04/2003 | ||

| Q340F1 | 10/01/2002 | Q340F1_BM | 10/01/2003 | Q340F4 | 11/05/2003 | Q340_F4BM | 11/05/2003 | ||

| Q363A | 03/12/2002 | Q363F3 | 27/03/2003 | ||||||

| Q367A | 31/12/2002 | Q367F3 | 17/03/2003 | ||||||

| Q435A | 02/03/2003 | Q435A2 | 02/03/2003 | Q435F1 | 07/04/2003 | Q435F1_BM | 14/04/2003 | Q435F2 | 18/06/2003 |

| Other sequenced African invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella Typhimurium used in the study | |||||||||

| A130 | 1997 | ||||||||

| D22827 | 2003 | ||||||||

| D22889 | 2003 | ||||||||

| D25734 | 2004 | ||||||||

| D25248 | 2004 | ||||||||

| D26275 | 2004 | ||||||||

| D25646 | 2004 | ||||||||

| D23580 | 2004 | ||||||||

Isolates from 14 individual patients (Q) with recurrent invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella Typhimurium disease, consisting of index presentation invasive isolates (A) and recurrent isolates at follow-up visits (F1, F2, F3 etc). Isolates are from 5 different tissues: blood (no suffix), bone marrow (_BM), stool (_S), throat (_TH) and urine (_U).

We detected high-quality discriminatory SNPs by mapping sequence reads to the Salmonella Typhimurium SL1344 reference sequence. Of the isolates, 43 were closely related to the Salmonella Typhimurium SL1344 reference, differing by 348–834 SNPs. The other 4 recurrent disease isolates, from participants Q23 and Q255, were found to differ from SL1344 by >12 000 SNPs (Table 3). Serotyping identified Q23A, Q23F1, and Q23F2_BM as S. Enteritidis, and this was concordant with their phylogenetic relationships. Isolate Q255F1_U was identified serologically as belonging to Salmonella group D and derived phylogenetically from the same branch as S. Enteritidis (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 3.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Differences for Recrudescence and Reinfection Isolates

| Index Isolate | Recurrent Isolate 1 | SNPs in Recurrent Isolate 1 | Recurrent Isolate 2 | SNPs in Recurrent Isolate 2 | Recurrent Isolate 3 | SNPs in Recurrent Isolate 3 | Recurrent Isolate 4 | SNPs in Recurrent Isolate 4 |

| Recrudescence | ||||||||

| Q18A | Q18A_S | 0 | Q18F2 | 0 | Q18F3_S | 0 | ||

| Q213F1a | Q213F1b | 2 | Q213F3_BM | 6 | ||||

| Q217A | Q217F3 | 0 | ||||||

| Q258A | Q258F3_BM | 1 | Q258F4 | 1 | ||||

| Q285A | Q285F1_BM | 2 | Q285F5 | 1 | ||||

| Q340F1 | Q340F1_BM | 1 | Q340F4 | 0 | Q340_F4BM | 0 | ||

| Q363A | Q363F3 | 0 | ||||||

| Q367A | Q367F3 | 1 | ||||||

| Q435A | Q435FA2 | 2 | Q435F1 | 2 | Q435F1_BM | 1 | Q435F2 | 1 |

| Reinfection | ||||||||

| Index Isolate | Recurrent Isolate 1 | SNPs in Recurrent Isolate 1 | Recurrent Isolate 2 | SNPs in Recurrent Isolate 2 | ||||

| Q175A | aQ175F4_TH | 5 | aQ175F6 | 470 | ||||

| Recrudescence and Reinfection | ||||||||

| Index Isolate | Recurrent Isolate 1 | SNPs in Recurrent Isolate 1 | Recurrent Isolate 2 | SNPs in Recurrent Isolate 2 | Recurrent Isolate 3 | SNPs in Recurrent Isolate 3 | ||

| Q23A | Q23F1 | 0 | Q23F2_BM | 0 | aQ23F5 | 38569 | ||

| Q134A | Q134F4 | 1 | aQ134F8 | 11 | Q134F9 | 11 | ||

| Q255A | Q255F1_BM | 0 | aQ255F2_U | 36974 | aQ255F4 | 9 | ||

| Q303A | aQ303F1 | 505 | Q303F3 | 508 | Q303F5 | 507 |

Abbreviation: SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Isolate that represents a reinfection at a mucosal or invasive site, with a nontyphoidal Salmonella pathovar that is phylogenetically distinct from the chronologically previous isolate. Isolates are labeled according individual patients (Q) with recurrent invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella Typhimurium disease, consisting of index presentation invasive isolates (A) and recurrent isolates at follow-up visits (F1, F2, F3 etc). Isolates are from 5 different tissues: blood (no suffix), bone marrow (_BM), stool (_S), throat (_TH) and urine (_U).

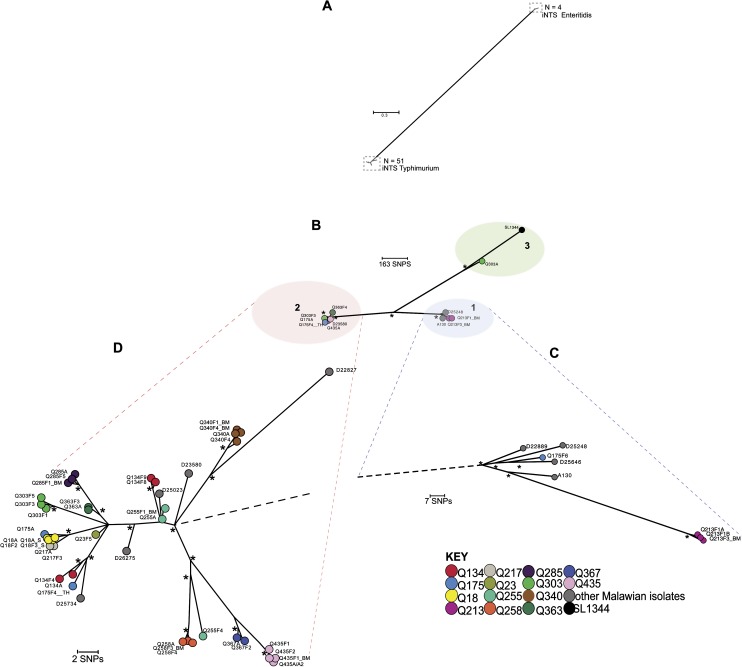

Figure 1.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees based on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) showing the relationship between invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella (iNTS) isolates associated with recurrent invasive disease. A, Unrooted tree based on 45 497 chromosomal SNP loci showing relationship of 51 iNTS Typhimurium isolates and 4 iNTS Enteritidis isolates. B, Unrooted phylogenetic tree based on 1463 chromosomal SNP loci of 51 iNTS Typhimurium isolates. Branch lengths are indicative of estimated rate of substitution per variable site. Length of scale bar is 0.09 substitutions per variable site or ∼163 SNPs. Asterisks indicate branches of the trees that were recovered using 4 independent methods with bootstrap support and clade credibility values greater than 70%. Phylogenetic clusters 1, 2, and 3 are bound by colored ellipses. C, Zoomed-in view of cluster 1. D, Zoomed-in view of cluster 2. In C and D, black dashed lines represent links to the rest of the tree. Scale bar and asterisks are as described previously. Isolate groups for each participant are colored according to the key. Index events and follow-up visits were denoted respectively by the suffixes ’A’ and ’F1,’ ’F2,’ ’F3,’ etc. Isolates grown from blood culture samples have no further suffix. Isolates from bone-marrow, stool, urine, or throat swabs were denoted respectively by the suffixes _BM, _S, _U or _TH.

The sequences of the 43 iNTS Typhimurium isolates from 14 patients and 8 control iNTS Typhimurium isolates were next subjected to a maximum-likelihood tree analysis to determine the overall population structure in fine detail. We confirmed this tree using several independent approaches, with bootstrap support and clade credibility marked. All the iNTS Typhimurium isolates from patients in the study fell within 3 distinct phylogenetic clusters (Figure 1B). Clusters 1 and 2 included 4 study isolates (9.3%) and 38 study isolates (88.4%), respectively. Both these clusters represented sequence type ST313 Salmonella Typhimurium strains. Cluster 3 contained only the index isolate Q303A (2.3%), which is most closely related isolate to the SL1344 reference.

Population Structure of Isolate Groups as a Basis to Define Recrudescence and Reinfection

Overall, >78% of recurrent isolates (25 of 32) represented recrudescence events among the samples we analyzed, and 13 of 14 participants demonstrated recrudescences during the study (Table 2). Of recurrent isolates, 22% (7 of 32) represented reinfections, and only 1 patient (Q175) had recurrences that were only a result of reinfection. A further 4 of 14 patients showed a combination of recrudescence and reinfection patterns.

Participants With Only Recrudescence

Isolate clusters from 9 patients—Q18, Q213, Q217, Q340, Q258, Q285, Q363, Q367, and Q435 (Figure 1C and 1D, Table 2)—suggested that all recurrent events for these participants were caused by recrudescence. We considered that these could be defined as recrudescent isolates as they were positioned in discrete clusters on individual phylogenetic branches and were highly genetically related, differing by only 0–6 SNPs (Table 3). Such SNP numbers could easily accumulate as the bacteria persist and replicate within the host. Whereas a single recrudescent isolate group, Q213, was found in cluster 1, the 8 other recrudescent isolate groups fell within cluster 2.

Participants With Only Reinfection

Other isolate pairs or series from the same individual fell on separate branches either within the same cluster or on different clusters, and we considered that these could be defined as likely reinfections, as later isolates could not be plausibly derived from earlier ones. The numbers of pairwise SNP differences were 5–508 within Salmonella Typhimurium serovars, and >12 000 between Salmonella Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis isolate pairs (Figure 1A, Table 3). For example, patient Q175 experienced only reinfections, at both a mucosal and an invasive site. The index and first recurrence isolates, Q175A and Q175F4_TH respectively, fell on different branches within cluster 2, despite only differing by 5 SNPs (Figure 1D), whereas a second recurrence isolate, Q175F6, was found in cluster 1 (Figure 1C).

Participants With Both Recrudescence and Reinfection

Isolate groups from 4 patients, Q23, Q134, Q255, and Q303, provided examples of disease recurrence resulting from combinations of recrudescence and reinfection within 1 participant (Figure 1D, Table 2). The index and recurrence isolates Q23A, Q23F1, and Q23F2_BM were identified as iNTS Enteritidis isolates, based on serology and phylogeny, and these F1 and F2 isolates were most likely early recrudescence episodes. A later invasive reinfection with an Salmonella Typhimurium isolate, Q23F5, was identified, which differed from the index S. Enteritidis cluster by >38 000 SNPs.

For participant Q134, the index and recurrence isolates, Q134A and Q134F4, formed a recrudescent pair differing by a single SNP but fell on a different phylogenetic branch within cluster 2 (Figure 1D) from a later reinfection isolate, Q134F8. Q134F9 thereafter represented a new recrudescent pair with Q134F8. The index and first recurrence isolates Q255A and Q255F1_BM formed an identical recrudescent pair; whereas a recurrence isolate, Q255F4, fell on a separate branch within cluster 2 (Figure 1D), which was indicative of a later invasive reinfection. Interestingly, the urine sample Q255F1_U had 36 974 SNP loci different from the index isolate and represented a mucosal reinfection with another NTS serovar, which was closely related to S. Enteritidis (Table 2, Supplementary Figure 1).

For participant Q303, only a single disease episode resulted from reinfection whereas all later isolates represented recrudescence. The index isolate Q303A, found in cluster 3 (Figure 1B), differed from the reinfection isolate Q303F1 found on a single phylogenetic branch in cluster 2, by >500 SNPs (Figure 1D, Table 2). Q303F1 subsequently showed recrudescence on 2 occasions (Q303F3 and Q303F5), when only 2–3 additional SNP differences were observed.

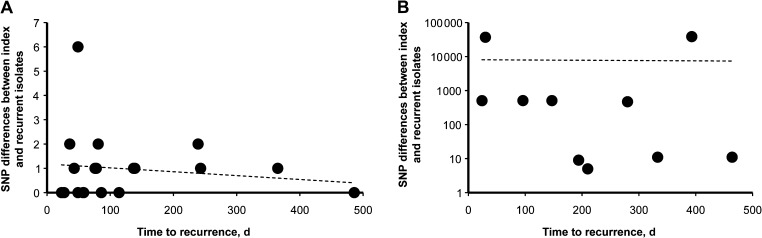

The time to recurrence ranged from 23 to 486 days between recrudescent pairs, and 24 to 464 days between reinfection pairs. The time to recurrence showed no correlation with the number of SNP differences between index and recrudescent isolates (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Linear regression plots of single nucleotide polymorphism differences between recrudescent pairs (A) and reinfection pairs (B) against time to recurrence. R2 values for A = 0.03; B = 0.0002. Abbreviation: SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

DISCUSSION

Recurrence of iNTS Typhimurium disease may be either a result of recrudescence, where the index isolate and the recurrent isolate are either genetically indistinguishable or plausibly phylogenetically derived one from the other, or a result of reinfection, where the subsequent recurrent isolate is phylogenetically distinct from the index isolate [6]. To explain the nature of recurrent iNTS disease, we analyzed isolate series from 14 patients with multiple recurrences of iNTS. The high-resolution SNP-typing and phylogenetic methods we used distinguished very closely related isolates to a degree not achievable by widely employed subgenomic typing tools. Our results reveal that both mechanisms are involved in recurrence of iNTS Typhimurium disease. Indeed, a combination of recrudescence and reinfection may frequently occur within an individual. This method therefore gives resolution superior to that seen in previous studies, which attempted to identify whether recrudescence [3] or reinfection [7] is the single most likely driver of recurrent iNTS disease. Crucially, we were able to identify reinfection with extremely closely related strains, where previous typing schemes with lower resolution would have inferred recrudescence.

The high recurrence rate we observed is a well-known feature of NTS infections associated with HIV infection [25–28]. The NTS might reemerge from a suppurative focus of infection (eg, endothelium, biliary or urinary tract, or musculoskeletal sites) [28–31] to cause recurrence, although we have not found this to be a frequent occurrence in our setting [3]. The larger study, from which the participants and isolates for this investigation were drawn [11], showed that there is an intracellular element of iNTS in HIV infection, that there is persistence and replication of NTS in the bone-marrow, and that recurrence is associated with an apparent failure of immunological control, all of which suggests that recrudescence from an intracellular sanctuary site might be the most likely explanation for recurrent iNTS disease in these patients.

Environmental factors such as contaminated food and water supplies, exposure to asymptomatic human carriers [31], or hospital-acquired infection [31, 32] could also potentially contribute to recurrent iNTS Typhimurium disease as a result of re-exposure and reinfection, especially in immunocompromised patients [33]. Clearly, repeated re-exposure might result in infection with a very closely related or identical isolate, or else with a new, unrelated isolate. Our study has not addressed these important possibilities, but there is an urgent need for comprehensive epidemiological investigation to understand the environmental reservoirs and transmission of NTS in sub-Saharan Africa. The methods we describe here would provide the resolution that would be critical for such investigations.

It is possible that there is heterogeneity in the population structure of Salmonellae within an individual, which could be underappreciated by sampling a single colony from each primary culture. We found, however, that 78% of recurrent isolates were near-identical to their preceding isolate, even from different sites and even over time. The data therefore point to the strain population within these individuals being homogeneous.

At the time of sampling (2002–2003), multidrug resistant (MDR) iNTS Typhimurium isolates (resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and cotrimoxazole) were epidemic in Blantyre, Malawi, accounting for >75% of iNTS isolates [4, 34]. Repeated treatment of index and recurrent disease with ciprofloxacin did not, however, prevent multiple recurrences. All but 1 of the Salmonella Typhimurium isolates identified in our study were of multilocus sequence typing sequence type 313 (ST313), a novel Salmonella Typhimurium pathovar that has been associated exclusively with invasive disease in Africa and which shows genome degradation suggesting host adaptation to humans [35]. During 2001, an MDR ST313 clade represented by D23580 (cluster 2) clonally replaced a previously dominant ST313 clade represented by A130 (cluster 1), in both Malawi and Kenya. It is therefore unsurprising that most of our study isolates were closely related to D23580, forming a highly clonal cluster with <450 chromosomal variable sites. Both clades have several drug resistance markers borne on a virulence plasmid, but both remain susceptible to fluoroquinolones [35].

Recrudescence was a commoner event than reinfection in our study: 78% of recurrent isolates represented recrudescence events, and 13 of 14 participants demonstrated recrudescences during the study. The number of days (23–486 d) between isolation of index and recurrent isolates had no obvious impact on the numbers of SNP differences accumulated, suggesting that these isolate groups comprise single clonal haplotypes with virtually no genetic change over time, despite exposure to multiple courses of ciprofloxacin. In contrast, 22% of recurrent isolates represented reinfections, and only 1 patient (Q175) had recurrences that were only a result of reinfection. A further 4 of 14 patients showed a combination of recrudescence and reinfection patterns. From our results, it was clear that recrudescences and reinfections could occur in either order, could occur over varying time scales, could occur multiply or singly, and could occur in either main cluster group.

We studied 4 incidences of infection with another iNTS serovar, Enteritidis, which accounted overall for 21% of iNTS events in Blantyre between 1998 and 2004 [4]. We have observed 1 incidence (Q255) of urinary reinfection with S. Enteritidis and 1 case (Q23) with an index series of recrudescent, invasive S. Enteritidis infections. These data are sufficient to demonstrate that, as with Salmonella Typhimurium, both reinfection with and recrudescence of S. Enteritidis may occur in HIV-associated iNTS disease.

Although sampling from mucosal sites was not as comprehensive as from invasive sites, the overall yield from mucosal sites was low, suggesting that prolonged mucosal carriage may be a relatively rare event. The nasopharyngeal and urine isolates (Q175F4_TH and Q255F2_U) represented incidences of later reinfection of the mucosa with a genetically different isolate, which was unrelated to any invasive isolates from the same individual. This is in contrast to the 2 stool samples (Q18A_S and Q18F3_S), which were longitudinally identical to the invasive isolates from the same participant, consistent with a hypothesis that the gut is the main site of invasion of iNTS.

Our results highlight the efficacy and applicability of whole-genome phylogenetics in understanding the pathogenesis of iNTS. The discriminatory power of this approach is likely to be equally necessary in a large-scale epidemiological investigation of this emerging pathogen.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online (http://www.oxfordjournals.org/our_journals/cid/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Financial support.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, United Kingdom (grant number 076964) and the Wellcome Trust Training Fellowship in Clinical Tropical Medicine to MAG; the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (grant number 098051) PhD fellowship to CKO.

Potential conflict of interest.

All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Ethical approval statement.

All participants gave written informed consent, and the study was approved by Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine Research Ethics committee and by the University of Malawi, College of Medicine Research Ethics Committee.

References

- 1.Graham SM. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis in Africa. Curr Opp Infect Dis. 2010;23:409–14. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833dd25d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy EA, Shaw AV, Crump JA. Community-acquired bloodstream infections in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:417–32. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon MA, Banda HT, Gondwe M, et al. Non-typhoidal Salmonella bacteraemia among HIV-infected Malawian adults: High mortality and frequent recrudescence. AIDS. 2002;16:1633–41. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200208160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon MA, Graham SM, Walsh AL, et al. Epidemics of invasive Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium infection associated with multidrug resistance among adults and children in Malawi. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:963–9. doi: 10.1086/529146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon MA. Salmonella infections in immunocompromised adults. J Infect. 2008;56:413–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wain J, Hien TT, Connerton P, et al. Molecular typing of multiple-antibiotic-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi from Vietnam: Application to acute and relapse cases of typhoid fever. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2466–72. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2466-2472.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubino S, Spanu L, Mannazzu M, et al. Molecular typing of non-typhoid Salmonella strains isolated from HIV-infected patients with recurrent salmonellosis. AIDS. 1999;13:137–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Islam A, Butler T, Ward LR. Reinfection with a different Vi-phage type of Salmonella typhi in an endemic area. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:155–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris SR, Feil EJ, Holden MT, et al. Evolution of MRSA during hospital transmission and intercontinental spread. Science. 2010;327:469–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1182395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croucher NJ, Harris SR, Fraser C, et al. Rapid pneumococcal evolution in response to clinical interventions. Science. 2011;331:430–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1198545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon MA, Kankwatira AM, Mwafulirwa G, et al. Invasive non-typhoid salmonellae establish systemic intracellular infection in HIV-infected adults: An emerging disease pathogenesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:953–62. doi: 10.1086/651080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–9. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt KE, Parkhill J, Mazzoni CJ, et al. High-throughput sequencing provides insights into genome variation and evolution in Salmonella Typhi. Nat Genet. 2008;40:987–93. doi: 10.1038/ng.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He M, Sebaihia M, Lawley TD, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of Clostridium difficile over short and long time scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7527–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914322107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: The manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acid Res. 2001;29:4633–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ning Z, Cox AJ, Mullikin JC. SSAHA: A fast search method for large DNA databases. Genome Res. 2001;11:1725–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.194201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–90. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (phylogeny inference package) [computer program]. Version 3.69. Seattle, Washington: Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington. Distributed by author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altekar G, Dwarkadas S, Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. Parallel Metropolis coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo for Bayesian phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:407–15. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corander J, Tang J. Bayesian analysis of population structure based on linked molecular information. Math Biosci. 2007;205:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corander J, Marttinen P, Siren J, Tang J. Enhanced Bayesian modelling in BAPS software for learning genetic structures of populations. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:539. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoiseth SK, Stocker BA. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291:238–9. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs JL, Gold JW, Murray HW, Roberts RB, Armstrong D. Salmonella infections in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:186–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-2-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nadelman RB, Mathur-Wagh U, Yancovitz SR, Mildvan D. Salmonella bacteremia associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1968–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith PD, Macher AM, Bookman MA, et al. Salmonella typhimurium enteritis and bacteremia in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:207–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-2-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine WC, Buehler JW, Bean NH, Tauxe RV. Epidemiology of nontyphoidal Salmonella bacteremia during the human immunodeficiency virus epidemic. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:81–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernández Guerrero ML, Ramos JM, Núñez A, de Górgolas M. Focal infections due to non-typhi Salmonella in patients with AIDS: Report of 10 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:690–7. doi: 10.1086/513747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hohmann EL. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:263–9. doi: 10.1086/318457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kariuki S, Revathi G, Kariuki N, et al. Invasive multidrug-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in Africa: Zoonotic or anthroponotic transmission? J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:585–91. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keddy KH, Dwarika S, Crowther P, et al. Genotypic and demographic characterization of invasive isolates of Salmonella Typhimurium in HIV co-infected patients in South Africa. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:585–92. doi: 10.3855/jidc.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morpeth SC, Ramadhani HO, Crump JA. Invasive non-Typhi Salmonella disease in Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:606–11. doi: 10.1086/603553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon MA, Graham SM. Invasive salmonellosis in Malawi. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2008;2:438–42. doi: 10.3855/jidc.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kingsley RA, Msefula CL, Thomson NR, et al. Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res. 2009;19:2279–87. doi: 10.1101/gr.091017.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.