Abstract

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels are heteromultimers of CaVα1 (pore), CaVβ- and CaVα2δ-subunits. The stoichiometry of this complex, and whether it is dynamically regulated in intact cells, remains controversial. Fortunately, CaVβ-isoforms affect gating differentially, and we chose two extremes (CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b) regarding single-channel open probability to address this question. HEK293α1C cells expressing the CaV1.2 subunit were transiently transfected with CaVα2δ1 alone or with CaVβ1a, CaVβ2b, or (2:1 or 1:1 plasmid ratio) combinations. Both CaVβ-subunits increased whole-cell current and shifted the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation to hyperpolarization. Time-dependent inactivation was accelerated by CaVβ1a-subunits but not by CaVβ2b-subunits. Mixtures induced intermediate phenotypes. Single channels sometimes switched between periods of low and high open probability. To validate such slow gating behavior, data were segmented in clusters of statistically similar open probability. With CaVβ1a-subunits alone, channels mostly stayed in clusters (or regimes of alike clusters) of low open probability. Increasing CaVβ2b-subunits (co-)expressed (1:2, 1:1 ratio or alone) progressively enhanced the frequency and total duration of high open probability clusters and regimes. Our analysis was validated by the inactivation behavior of segmented ensemble averages. Hence, a phenotype consistent with mutually exclusive and dynamically competing binding of different CaVβ-subunits is demonstrated in intact cells.

Introduction

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ (CaV) channels are found in all types of excitable cells and play a unique role in the transduction of electrical signaling into various physiological Ca2+-dependent processes including muscle contractions, synaptic plasticity, and gene expression (1). Ten distinct pore-forming (CaVα1) subunits identified by molecular cloning lead to functional diversity through differences in their biophysical properties (1). L-type Ca2+ channels are heteromultimeric complexes composed of a pore-forming CaVα1 subunit (from the CaV1 family) and auxiliary subunits CaVβ and CaVα2δ (1). CaVβ subunits are ∼500-amino-acid cytoplasmic proteins encoded by four genes (CaVβ1–4) with multiple alternatively spliced variants (2). CaVβ subunits bind to a conserved 18-residue sequence in the CaVα1 I-II intracellular loop called the α-interaction domain (AID) (3,4). Among the auxiliary subunits, CaVβ subunits play a central role in functional aspects of high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels including CaV1 and CaV2 channels: e.g., in surface expression, activation, inactivation, and regulation by other proteins; and the effects of CaVβ-subunits are isoform-specific (2). Therefore, the association of CaVα1 and CaVβ subunits is crucial for proper channel biophysical phenotype and cell surface expression of HVA Ca2+ channels.

Sequence homology analysis, confirmed by high-resolution x-ray crystallography, revealed that CaVβ subunits consist of five domains arranged as V1-C1-V2-C2-V3, where V1, V2, and V3 are variable N-terminus, HOOK, and C-terminus domains, respectively, and C1 and C2 form conserved Src homology 3 and guanylate kinase (GK) domains, respectively (reviewed in Buraei and Yang (2)). The high-affinity CaVα1-CaVβ interaction takes place between the AID α-helix and the α-binding pocket (ABP) in the CaVβ GK domain (5–7).

Despite the high (2–54 nM, reviewed in Buraei and Yang (2)) affinity of the ABP-AID interaction found in vitro, whole-cell electrophysiology experiments provide indirect evidence that the interaction between CaVα1 and CaVβ can be quite dynamic in intact cells. For instance, modulation of gating by adding (or removing) a (different) CaVβ can be observed within <1 h (8), within some 10 min (9), or even within a few seconds if the binding affinity is reduced by mutagenesis (10). In addition, the concentration dependence of the interaction between different CaVβ isoforms argues in favor of a competitive replacement at a unique high-affinity binding site (11). Altogether, the interaction between CaVα1 and CaVβ can be assumed to be rather rapidly reversible in a physiological context (reviewed by Buraei and Yang (2)).

However, to date, a direct demonstration and mechanistic explanation for reversible binding, and hence the possibility of competition between CaVβ subunits in modulating HVA Ca2+ channel gating, has not been accomplished in intact mammalian cells. In this work, we studied competition of CaVβ subunits for recombinant CaV1.2 L-type Ca2+ channels in heterologous expression system of intact HEK293 cells. We employed the fact that different CaVβ subunits and their splice variants lead to distinct single-channel gating properties of recombinant CaV1.2 channels (12–14). For example, we have previously identified that a prevalent CaVβ subunit isoform in human heart, CaVβ2b (12), is capable to inhibit inactivation of CaV1.2 channels (13,14). In contrast, CaVβ1a promotes rapid inactivation of CaV1.2 channels (15) and confers a much lower open probability (14).

In this work, CaVβ1a or CaVβ2b subunits or their 1:1 and 2:1 (plasmid ratio) mixtures were overexpressed with CaV1.2 channels in HEK293 cells. We used similar transfection protocols to record both whole-cell and single-channel current. At whole-cell level, CaVβ subunits increased current density, displaced the peak of voltage current relationship to hyperpolarized potentials, and modulated steady-state inactivation. As predicted, the inactivation rate was gauged by varying the proportion of the (co-)transfected CaVβ1a subunit. Single-channel recording and elaborate statistical data analysis provided more direct evidence of dynamic replacement of CaVβ subunits, which spontaneously took place at single-channel level on the timescale of minutes.

Materials and Methods

Expression vectors for L-type Ca2+ channel auxiliary subunits

See the Supporting Material.

Cell culture and transfection

For patch-clamp experiments, HEK293α1C cells stably expressing human cardiac CaV1.2 subunits were transiently transfected with pIRESpuro3-α2δ1 and either pIRES2-DsRed2-β1a, pIRES2-EGFP-β2b or the mixtures of pIRES2-DsRed2-β1a and pIRES2-EGFP-β2b (2:1 or 1:1 by DNA mass). See the Supporting Material for details.

Patch-clamp measurements and analysis

All recording were made using an Axopatch 1D amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) with pClamp 5.5 data acquisition software (Axon Instruments). Recordings were performed 48–72 h after transfection at room temperature (19–23°C) using whole-cell or cell-attached voltage-clamp of successfully transfected cells, which were identified on the basis of either EGFP, DsRed2, or both EGFP and DsRed2 fluorescence. Whole-cell and single-channel Ba2+ currents were performed as reported in Herzig et al. (13) and Jangsangthong et al. (15).

Whole-cell external recording solution contained 10 mM BaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 65 mM CsCl, 65 mM TEA-Cl, 10 mM dextrose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.3 with TEA-OH). Whole-cell internal solution contained 140 mM CsCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 4 mM Mg-ATP, 10 mM EGTA, and 9 mM HEPES (pH 7.3 with CsOH). Holding potential in whole-cell experiments was −100 mV. To obtain current-voltage (I/V) relationships, cells were depolarized for 160 ms from the holding potential to voltages ranging from −40 to +60 mV, applied every 5 s. See the Supporting Material for analysis.

Single-channel depolarizing bath solution consisted of 120 mM K glutamate, 25 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na2-ATP (for sake of comparison with previous studies), 10 mM dextrose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.3 with KOH). Single-channel pipette solution contained 110 mM BaCl2 and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.3 with TEA-OH). Single-channel Ba2+ currents were evoked in cell-attached configuration by rectangular voltage pulses to the test potential 10 mV from the holding potential –100 mV. The pulse duration and repetition rate were 150 ms and 1.67 Hz (100 sweeps/min), respectively. Single-channel data were processed as described previously (13,15). Experiments were analyzed only when the channel activity persisted for at least 108 s (≥180 sweeps) and no stacked openings were observed. Routinely, at least 9 out of 10 experiments had to be discarded because of the stacked openings.

In the remaining datasets, we calculated the probability pN=1 that the absence of stacked openings firmly indicates the absence of multiple functional channels (not shown). Although this value was low on the case of CaVβ1a, robust estimates were obtained in the groups with higher overall single channel open-probability (2:1 mixture of CaVβb1a and CaVβ2b: pN = 1 = 0.62 + −0.15, n = 5; 1:1 mixture of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b: pN=1 = 0.76 + −0.08, n = 4; CaVβ2b alone: pN=1: 0.90 + −0.06, n = 8).

Statistics

Unless otherwise stated, data were reported as mean ± SE. Statistical comparison of several groups to a control group was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post-test. Statistical comparison of several groups to each other was performed by the Holm-Bonferroni method. The significance level was p < 0.05. The term “n” refers to the number of experiments.

Segmentation of the open-probability diary

Single-channel open-probability diary was constructed by calculating open probability for every sweep in a single-channel experiment. Sweep open probability was defined as the total open time in a given sweep divided by the pulse duration (150 ms). Open-probability diary was segmented into clusters with statistically different single-channel activity using a bottom-up merging strategy (similar to Kuzmenkina et al. (16)). The following algorithm was employed by our homemade software. To begin, the open-probability diary was split into groups of five consecutive sweeps. Then, the statistical distance, dk, k+1, between neighboring groups, k and k+1, was calculated as

| (1) |

where the value pdiff k, k+1 was the probability that the average open probabilities of two compared groups were different, which was calculated by either exact or Monte Carlo permutation tests. Monte Carlo permutation test with 20,000 trials was applied whenever the number of possible permutations was >7000. The second factor in Eq. 1, f, was an empirical correction factor, which forced the program to merge short groups first and was negligible for large groups. The correction factor, of the following form, was tried and was not optimized further:

| (2) |

Here, Nk and Nk+1 were the number of sweeps in the compared groups.

The groups with the smallest statistical distance between them were fused. Then new distances were calculated and statistically closest groups were merged until all dk, k+1 were larger than 0.999. In some cases, dk, k+1 > 0.9995 or 0.9999 were used. Such high values were required to correct for multiple testing during the segmentation procedure.

To finally prove that identified temporal clustering of the open-probability was not an artifact due to multiple comparisons, we generated 200 randomized open probability diaries for every experiment and applied our segmentation procedure to them. Randomized open-probability diaries were obtained from the original open-probability diaries by the bootstrapping (17). In every experiment, the fraction of such randomized open-probability diaries, which were split into two or more clusters, was <5%.

Open-probability clusters were classified into low- and high-open-probability regimes using a threshold of the mean open probability within a cluster at 0.0037. Importantly, there were no secular changes in open-probability over time in our experiments (i.e., “run down”, not shown).

Calculation of lifetimes

Average lifetimes of open-probability clusters were calculated as the total observation time divided by the number of the transition between clusters. Average lifetimes of low- or high-open-probability regimes were calculated as the total observation time of the respective type of the channel activity divided by the number of transitions from the given type of the channel activity to a different channel activity (from low to high, or from high to low). Standard errors were estimated by the jackknife method.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

See the Supporting Material.

Results

Whole-cell currents revealed concurrent heterologous expression of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits

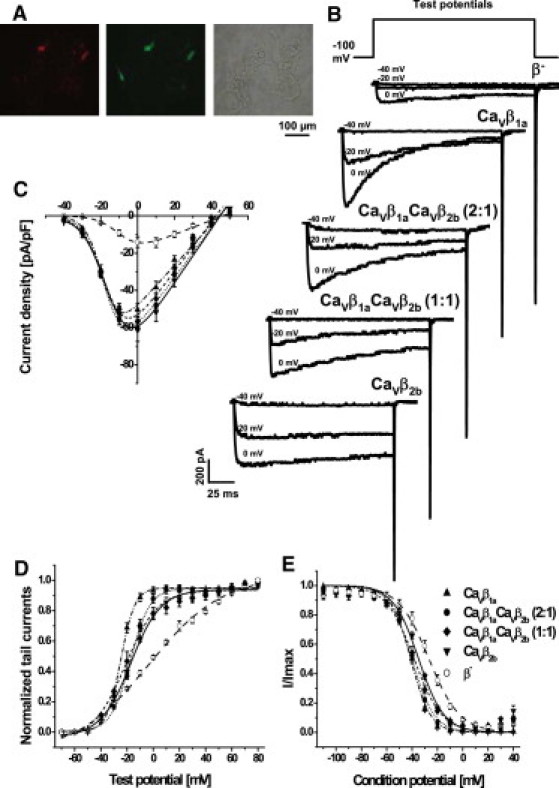

To study how different CaVβ subunits modulate gating of CaV1.2 channels, either CaVβ1a, CaVβ2b or mixtures of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits were heterologously coexpressed with CaVα2δ1 subunit in HEK293α1C cells that stably expressed a Cav1.2 subunit cloned from human heart. Fluorescent imaging revealed red fluorescence of DsRed2 colocalization with green fluorescence of EGFP that reported expression of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits, respectively, indicating the presence of both CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits in those cells (Fig. 1 A). Whole-cell Ba2+ current density of CaV1.2 channel complexes containing CaVβ subunits were 3.5−4-fold higher compared to the channels from mock-transfected cells (Fig. 1, B and C, and see Table S2 in the Supporting Material). Furthermore, expression of CaVβ subunits shifted the voltage of half-maximal activation to hyperpolarizing potentials, with a significantly stronger shift induced by CaVβ1a subunits in comparison to CaVβ2b subunits (Fig. 1 D and see Table S2). Steady-state inactivation (induced by a 5-s conditioning pulse) was also shifted to more negative voltages by CaVβ subunits, with the strongest shift induced by CaVβ1a subunits (Fig. 1 E and see Table S2). In CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b competition experiments, inactivation curves lay between CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b curves in agreement with the relative amount of CaVβ1a subunits being transfected (Fig. 1 E and see Table S2).

Figure 1.

Whole-cell current properties of CaV1.2 channels modulated by CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits and their mixtures. (A) Micrographs showing HEK293α1C cells after transfection with vectors encoding CaVβ and CaVα2δ1 subunits. (Red and green fluorescences) DsRed2 and EGF proteins reporting expression of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits, respectively, in the cells. (B) Representative whole-cell Ba2+ current traces. CaVβ subunits used for transfections are indicated above the traces. (C–E) Properties of CaV1.2 channels in β− cells (open circles, n = 5), and in cells cotransfected with CaVβ1a (up-pointing triangles, n = 9), CaVβ1aCaVβ2b mixture (2:1) (solid circles, n = 8), CaVβ1aCaVβ2b mixture (1:1) (solid diamonds, n = 6), and CaVβ2b (down-pointing triangles, n = 6). Symbols with error bars represent mean ± SE. Curves show fits of the average data. (C) I/V curves were obtained by depolarizing from –100 mV holding potential to test voltages between –40 and +60 mV. The data were fitted with a Boltzmann-Ohm function. (D) Activation curves were obtained from fitting of normalized tail currents with a Boltzmann function. (E) To study the steady-state inactivation, peak current amplitudes at +10 mV were measured immediately after a 5-s conditioning potential. The data were fitted using the Boltzmann equation.

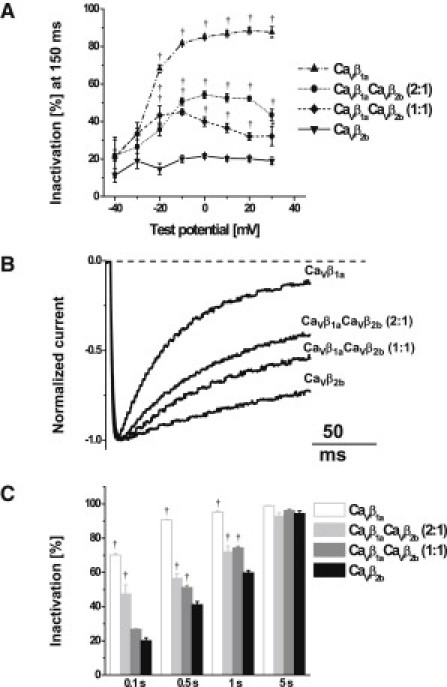

As seen in Fig. 1 B, expression of CaVβ1a subunits accelerated inactivation of CaV1.2 channels. This inactivation was not purely monoexponential on the second timescale (data not shown). To address the early component of the inactivation, we determined the percentage of the whole-cell Ba2+ current that had inactivated after 150 ms of depolarization (Fig. 2 A). For test potentials –20 mV and above, CaVβ1a subunits induced faster inactivation than CaVβ2b subunits (note that steady-state inactivation with CaVβ2b at –20 mV was 80%, Fig. 1 E). The mixtures of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits showed an intermediate extent of the fast inactivation. From 0 mV and above, the extent of the fast inactivation in CaVβ1a CaVβ2b mixture experiments was larger when more plasmid DNA encoding CaVβ1a subunits was transfected. To exemplify these findings, Fig. 2 B shows normalized representative whole-cell Ba2+ currents evoked by 160-ms depolarization to +10 mV. Fig. 2 C presents the average time course of inactivation at +10 mV over 5 s of depolarization. According to our previous observations, the inactivation was promoted by CaVβ1a; accordingly, the lower the ratio of CaVβ1a subunits to CaVβ2b subunits, the slower the inactivation.

Figure 2.

Inactivation kinetics of CaV1.2 channels modulated by CaVβ subunits and their mixtures. (A) Voltage dependence of the inactivation rate (determined as the fraction of peak current inactivated after 150 ms of depolarization) of CaV1.2/α2δ1 coexpressed with CaVβ1a subunit (up-pointing triangles, n = 6), CaVβ1aCaVβ2b combination (2:1) (solid circles, n = 5), CaVβ1aCaVβ2b combination (1:1) (solid diamonds, n = 5), and CaVβ2b subunit (down-pointing triangles, n = 6), respectively. (B) Normalized representative Ba2+ currents through CaV1.2 channels traces evoked by 160 ms depolarization to +10 mV. (C) Percent of the current inactivation at 0.1-, 0.5-, 1-, and 5 s during 5-s test pulses to +10 mV. (Open, light-shaded, medium-shaded, and solid bars) CaVβ1a subunit (n = 5), CaVβ1aCaVβ2b combination (2:1) (n = 4), CaVβ1aCaVβ2b combination (1:1) (n = 4), and CaVβ2b subunit (n = 6) experiments, respectively. ∗p < 0.05; †p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post-test compared with CaV1.2 channels containing CaVβ2b subunits. The apparent differences between the two mixtures of CaVβ1aCaVβ2b are not significant.

Taken together, the gating properties of whole-cell currents in CaVβ1aCaVβ2b mixtures were intermediate between the properties of CaVβ1a- and CaVβ2b-modulated channels, verifying concurrent heterologous expression of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits.

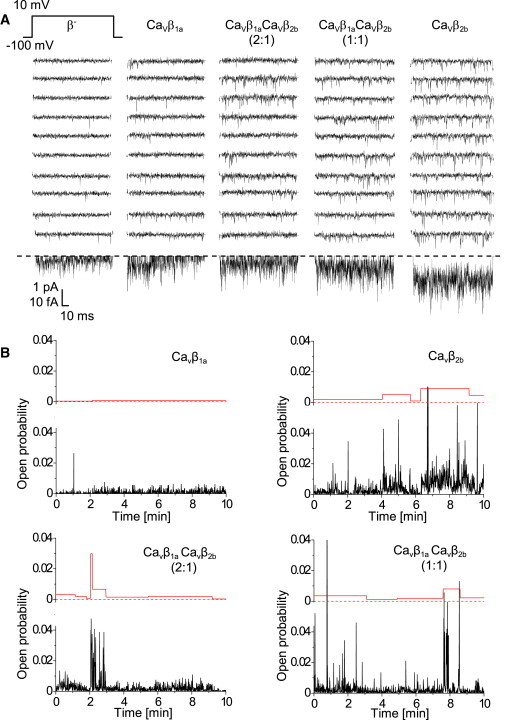

Coexpression of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits gradually modulated average single-channel characteristics

Effects of CaVβ subunits on unitary currents were studied in cell-attached patches, with 110 mM Ba2+ in the pipette solution (holding potential –100 mV, test potential +10 mV). Fig. 3 A shows representative current traces and ensemble average currents of single CaV1.2 channels with the two CaVβ subunits and their combinations. Transfection of CaVβ subunits modified gating of single channels as compared to the mock-transfection: CaVβ1a and CaVβ1aCaVβ2b (2:1) transfections resulted in higher time-dependent inactivation, whereas CaVβ1aCaVβ2b (1:1) and CaVβ2b led to higher channel availability and open probability (see Table S3). Within the series of different CaVβ experiments, all average single-channel characteristics progressively changed according to the relative amount of transfected CaVβ2b. The most pronounced effects were for channel availability, open probability within active sweeps, and peak current (from low values for CaVβ1a to high values for CaVβ2b) and for inactivation (from high inactivation for CaVβ1a to low inactivation for CaVβ2b).

Figure 3.

Single-channel recordings of CaV1.2 channels modulated by CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits and their mixtures. (A) Exemplary single-channel Ba2+ current traces of CaV1.2 channels after transient coexpression of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunit as indicated. (Top row) Pulse protocol (150-ms pulses applied every 600 ms). (Middle) Ten representative consecutive traces are shown for each CaVβ subunit combination. (Bottom rows) Respective single-channel average currents (from at least 180 traces recorded per experiment). (B) Single-channel open probability fluctuates on a minute timescale. Diaries of single-channel open probability (lower panels of each graphs with noisy lines) were automatically split into temporal clusters with statistically significantly different mean open probability values (upper panels of each graph).

Open probability of single CaV1.2 channels fluctuated on the minute timescale

By visual inspection of the open-probability diaries of single CaV1.2 channels, we had the impression that the channel open probability fluctuated on the minute timescale (Fig. 3 B). To statistically prove and analyze in detail changes in the channel activity over time, we segmented open-probability diaries into temporal clusters demarcated by statistically significant differences of open probability. As negative controls, we constructed 200 randomized open-probability diaries for each experiment and applied the segmentation procedure to them. In all experiments, the fraction of negative controls where clusters were found was <5%.

With our segmentation procedure, we found fluctuations of the open probability only in half of the experiments with CaVβ1a, in the majority of the experiments with CaVβ2b, and in all experiments where CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b were coexpressed (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). Moreover, modulation of the open probability in the case of CaVβ1a alone was much smaller than in the presence of CaVβ2b subunits (Fig. 3 B).

Average lifetimes of the resolved clusters were similar (CaVβ1a: 3.9 ± 1.7 min, n = 8 experiments; CaVβ1aCaVβ2b (2:1): 2.1 ± 0.4 min, n = 5; CaVβ1aCaVβ2b (1:1): 3.3 ± 1.6 min, n = 4; and CaVβ2b: 2.3 ± 0.4 min, n = 8). However, we will demonstrate below that, for more accurate analysis, clusters should be grouped according to the level of channel activity.

The following analysis was performed using open-probability clusters from our segmentation procedure. The term “cluster open probability” refers to the mean open probability of a given cluster.

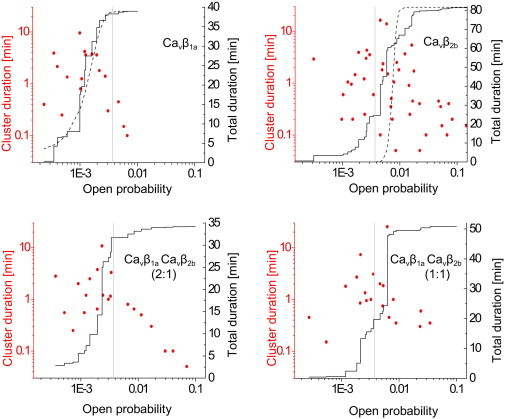

Low- and high-activity regimes of the channel gating

Interestingly, we found that distribution of the cluster-open probabilities from CaVβ1a experiments could be described as a single Gaussian (Fig. 4). By contrast, distribution of the cluster-open probabilities from CaVβ2b experiments were spread over two decades and could not be fitted either by one (Fig. 4) or by two (data not shown) Gaussians. This indicates that CaVβ2b subunits induced multimodal gating behavior and agrees with the observation that periods of high channel activity in CaVβ2b experiments alternates with periods of low activity (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 4.

Multiregime behavior in the presence of CaVβ2b subunits. Symbols show distribution of open probabilities and durations of resolved clusters (left Y axis). (Solid lines) Cumulative distribution of cluster open probabilities (right Y axis). (Dashed lines) Cumulative normal distributions with means and variances obtained from the statistics of cluster's open-probability values, weighted by the durations of the clusters. In the case of CaVβ1a, a good agreement between the experimental and the theoretical normal open-probability distributions is seen. By contrast, in the case of CaVβ2b, the predicted normal distribution is much narrower than the observed open-probability distribution, indicating that channels switch between high- and low-open-probability regimes. The threshold to separate high-open-probability (CaVβ2b-like) from low-open-probability (CaVβ1a-like) regimes was set at open probability = 0.0037 (vertical shaded lines), which is equal to the mean + SD of the open-probability distribution from CaVβ1a experiments.

Note that, for further analysis, we prefer to use the word “regime” instead of “mode”. This is because the term “mode” is habitually used to describe features of the gating behavior that become evident on a single-sweep basis, rather than the average activity during a sequence of sweeps (open-probability clusters). To separate a high-open-probability behavior typical for CaVβ2b experiments from a low-open-probability regime found in CaVβ1a experiments, we used a threshold at the cluster-open probability = 0.0037. The value of the threshold was set to the mean + SD of the cluster-open-probability distributions from CaVβ1a experiments (weighted by cluster length; and see Fig. 4).

Single CaV1.2 channels in CaVβ2b and CaVβ1aCaVβ2b mixture experiments robustly exhibited gating in the high-open-probability regime (Fig. 5 A). Whereas single CaV1.2 channels in CaVβ2b experiments stayed predominantly in the high-open-probability regime, the fraction of time spent in the high-open-probability regime decreased with more of CaVβ1a being cotransfected (Fig. 5 B). Consistently, in the case of CaVβ1a transfections, channels were almost exclusively in the low-open-probability regime. Altogether, these results suggest that the low- and high-activity regimes reflect association of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits with the channel complex, respectively.

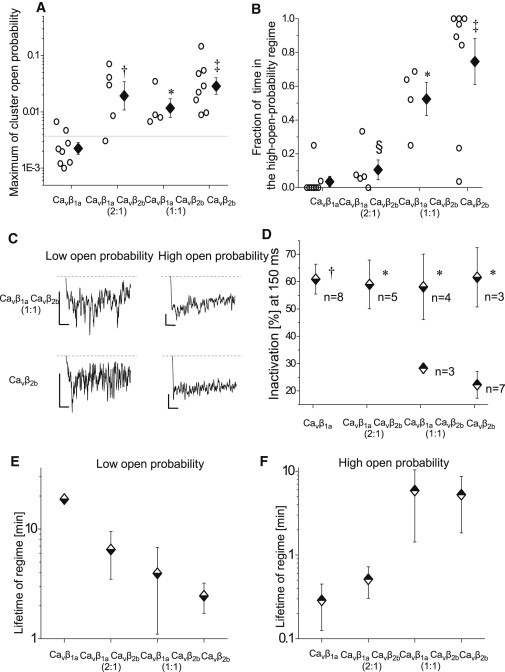

Figure 5.

Properties of low- and high-open-probability regimes. (A and B) Experiments with CaVβ2b subunits (alone or in mixture experiments) robustly showed high-open-probability clusters (A). Moreover, the fraction of time spent in the high-open-probability clusters increased with more of CaVβ2b being cotransfected (B). Open circles show values from each experiment. (Diamonds with error bars) Logarithmic (A) or arithmetic (B) group means ± SE. All group means were compared using the Holm-Bonferroni method. ∗p < 0.05, †p < 0.01, and ‡p < 0.001 compared with CaVβ1a experiments; §p < 0.001 compared with CaVβ2b experiments. (C and D) High-open-probability clusters were characterized by a lower inactivation of the average current. (C) Exemplary average currents of the low-open-probability (left) and high-open-probability (right) regimes from the same single-channel experiments. For better visibility, a moving average of 15 points is shown. Graphs are scaled to the same peak current level (the lowest value of moving average of 100 points). (Scale bars) Vertical, 2fA; and horizontal, 20 ms. (D) Inactivation of average currents after 150 ms during low (half-down diamonds) and high (half-up diamonds) open-probability clusters (mean ± SE). For each experiment, all clusters with either high- or low-open-probability were pooled together. Data were used for the analysis only if the pooled duration of the respective clusters was longer than 100 episodes. The value n is the number of experiments with sufficient statistics. All group means were compared using Holm-Bonferroni method. ∗p < 0.05 and †p < 0.01 compared with high-open-probability clusters of CaVβ2b experiments. (E and F) Lifetimes of low- and high-open-probability regimes. Low- or high-activity regimes were defined as consecutive clusters of the same type of the channel open probability (low or high, respectively). Mean lifetimes and errors were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Errors for the lifetime of the low-open-probability regime in CaVβ1a experiments could not be estimated because transitions from the low- to high-activity regime occurred only in one experiment.

Low- and high-open-probability regimes of the channel activity revealed different inactivation kinetics

To substantiate our analysis by a second and rather different biophysical parameter, we studied time-dependent inactivation during low-and high-open-probability regimes. To reduce data noise, for each experiment, we pooled all low- or high-open-probability clusters together to construct respective low- or high-open-probability subset ensemble average single-channel currents. In half of CaVβ2b and CaVβ1aCaVβ2b mixture experiments, which showed both low and high channel activity, the extent of the inactivation of the average single-channel currents was higher for the low-open-probability regime (Fig. 5 C). In the rest of the experiments, the inactivation properties were not distinguishable within statistical noise. Accordingly, the mean extent of the inactivation was higher in the low- than in the high-open-probability regimes (Fig. 5 D). Subset ensembles—as far as they could be analyzed—mirrored inactivation properties of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits, respectively (Fig. 5 D and see Table S3).

Apparent lifetimes of the low- and high-open-probability regimes

Next, we determined average lifetimes of low- (CaVβ1a-like) and high- (CaVβ2b-like) open-probability regimes to estimate the exchange rate of CaVβ-subunits (Fig. 5, E and F). Additionally, Fig. S2 shows lifetimes of resolved clusters within low- or high-channel-activity regimes. Clusters were defined by our segmentation procedure as a sequence of sweeps with similar channel activity. By contrast, for the lifetime analysis, low- and high-open-probability regimes were defined as consecutive clusters of the same type of the channel activity (low or high). Both ways of the analysis produced similar results. From our data, lifetime of the high-open-probability regime from CaVβ1aCaVβ2b (2:1) experiments can serve to estimate the lifetime of CaVβ2b subunits in the channel complex. The increase of the apparent lifetimes of the high-open-probability regime at higher relative CaVβ2b amounts (CaVβ1aCaVβ2b (1:1) and CaVβ2b experiments) may have resulted from the several CaVβ2b subunits consecutively binding to the channel complex. The higher the ratio of the transfected CaVβ1a/CaVβ2b subunit, the more we observed an increase of the apparent lifetime of the low-open-probability regime.

Endogenous expression of CaV subunits in HEK293 cells

Endogenous CaVβ3 subunits were found in HEK tsA-201 cells (18). The presence of endogenous CaVβ subunits can explain why, when only CaVβ2b subunits were transfected, CaV1.2 channels spent a small fraction of time in the low-activity regime (Fig. 5 B). Indeed, using a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, we found mRNA for endogenous CaVβ1, CaVβ2, CaVβ3, and CaVβ4 subunits as well as for the pore-forming CaVα1C subunits in HEK293 and HEK293α1C cells (see Fig. S3, A and B). In HEK293α1C cells, mRNA level for the pore-forming subunits was elevated by a factor of 46 (see Fig. S3 C).

Discussion

Switching between low and high channel activity likely reflects an exchange of CaVβ subunits

In this work, we showed that simultaneous heterologous overexpression of different CaVβ subunits (CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b) produced calcium channels with gating phenotypes intermediate to the gating phenotypes of calcium channels containing only one type of transfected CaVβ subunit. These intermediate average gating characteristics resulted from the switching between CaVβ1a- and CaVβ2b-like behaviors of individual channels on the minute timescale.

We provided statistical evidence of the switching by the data segmentation analysis. Our segmentation analysis allowed us to investigate long-time correlation in the channel activity. This is in contrast to the run analysis, which focuses on the short-time correlations. Because definition of the gating modes is associated with the categorization of individual sweeps eventually followed by the analysis of runs or correlations between consecutive sweeps (19–24), we consistently avoided the term “mode” in our article. Our low- and high-activity “regimes” can include several modes with a particular equilibrium between them reflected by the mean cluster open-probability.

Interestingly, we found that, when CaVβ2b as an only CaVβ subunit was used for the transfection, channels still spent a minor fraction of time in the low-activity regime. To compare, Luvisetto et al. (23) observed that CaV2.1 channels coexpressed with one type of CaVβ subunits in HEK293 cells switched between different types of the channel activity also on the minute timescale (no detailed analysis on the switching kinetics was performed). The authors favored the hypothesis that the switching reflected a slow equilibrium between modes (specific for CaV2.1) rather than dynamic exchange of heterologously expressed CaVβ subunits with endogenous ones. However, the latter possibility cannot be excluded as the expression of endogenous CaVβ subunits in HEK cells was reported previously (18) and confirmed in this work. Of note, mode switching as induced by covalent modification through cAMP-dependent phosphorylation typically occurs on a faster timescale of a few seconds (20,25).

Importantly, we found that coexpression of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits in 2:1 by the DNA mass ratio largely shortened the high-open-probability regimes indicating that, at this condition, the duration of the high-activity regime was limited by the lifetime of a CaVβ2b subunit in the channel complex.

Thus, our study suggests dynamic exchange of CaVβ subunits as an additional mechanism in regulation of CaV channels in vivo.

Affinity and reversibility of the CaVβ and CaVα1 binding

The main anchoring site for CaVβ is AID in the intracellular I-II loop of CaVα1 subunits. The dissociation constant (Kd) of CaVβ subunits with AID peptide or full-length I-II linker is 2–54 nM (2). Affinity of CaVβ to nascent CaVα1 subunits (judged by the current increase after injection of CaVβ subunits in Xenopus oocytes) appears to be the same (26,27). However, the affinity to CaVα1 incorporated in the plasma membrane (addressed by voltage shifts of the activation and inactivation) remains less certain: Geib et al. (26) measured Kd values of 3.5 to tens of nM, depending on isoform, whereas other groups reported values of 120–350 nM (11,24,27).

Multiple works suggest that the CaVα1-CaVβ interaction is reversible in intact cells. For example, endogenous CaVβ subunits aid trafficking of CaVα1 to the plasma membrane (28) but allow rapid gating modulation by exogenously delivered CaVβ subunits (8,9). Gating properties of CaVα1 in oocytes in the presence of endogenous CaVβ3XO are different from the gating properties when CaVβ3XO is additionally exogenously overexpressed (22). From this, it was proposed that endogenous CaVβ subunits dissociated from the CaVα1 channels after chaperoning them to the plasma membrane. Likewise, an injection of CaVβ2a subunits into oocytes with CaV2.3/CaVβ1b channels converted the fast channel inactivation induced by CaVβ1b subunits to the slow inactivation, indicating that CaVβ2a subunits took over the channels (11).

Competition conditions may accelerate full dissociation of a CaVβ-CaVα1 complex

Initial experiments showed that the formation and dissociation of CaVβ-AID complexes required hours and more than tens of hours, respectively (4). However, surface plasmon resonance studies revealed that the association of CaVβ with AID or the I-II linker occurred with the rate of 2–6 × 105 M−1 s−1 (26,27). For our estimate of the dissociation time of ∼30 s, this gives numerically an affinity constant of ∼100 nM. In the surface plasmon resonance experiments, the dissociation rates were on the minute timescale. It was pointed out that the dissociation rates from such experiments may be underestimated due to the rebinding of the ligand (27). Indeed, competition conditions can accelerate dissociation of CaVβ-AID/CaVα1 complexes. For example, a half-dissociation time of CaVβ3 bound to the I-II linker in the presence of AID-derived peptides was only 28 s (29). Similarly, although modulation of the current through CaVα1 subunits by CaVβ subunits was stable in excised inside-out patches for up to 30 min (10,30), the presence of the competitive AID peptide quickly removed this modulation (30). It was proposed that multiple CaVα1-CaVβ interaction sites led to formation of a ternary complex of CaVα1, CaVβ and the AID peptide with lower stability (30). It was further suggested that a similar step-by-step binding mechanism can lead to exchange of CaVβ subunits in CaV channels in vivo.

Alternatively, low-affinity interaction sites can transiently trap a CaVβ subunit released from AID, thus allowing its effective rebinding. CaVβ subunits from cytoplasm can interfere with this mechanism by competing for the binding to the lower-interaction sites or to the freed AID. Low-affinity interaction sites for CaVβ subunits were found in the C- and N-terminal tails of CaVα1 subunit, and in the I-II linker outside of AID (28,31–34) Moreover, CaVα1 and CaVβ subunits may interact nonspecifically (for example, a current through CaVα1 was upregulated by a random 43-amino-acid peptide (5)). This work demonstrated that, indeed, under conditions facilitating competition, CaVβ subunits can displace each other on a physiologically relevant short timescale of minutes. However, the exact mechanism and, in particular, a role of secondary binding sites, therein require further investigations.

Oligomerization of CaVβ subunits

So far, we considered the widely accepted 1:1 stoichiometry of CaVα1-CaVβ complex (2), thus assuming that CaVβ subunits are monomeric proteins. However, it was recently demonstrated that CaVβ subunits can form functional homo- and heterooligomers (35,36), and our data do not firmly rule out this possibility. Lao et al. (35) found that the current-voltage relationship and inactivation kinetics of CaV1.2 channels with mixture of CaVβ2d and CaVβ3 subunits could not be explained by a mixture of CaV1.2 channels with either CaVβ2d or CaVβ3 subunits. By contrast, in our work, all whole-cell and average single-channel characteristics for mixtures of CaVβ1a and CaVβ2b subunits could be interpreted in terms of a mixture of populations of CaV channels with either CaVβ subunits. However, very wide distribution of single-channel cluster open probability in the presence of CaVβ2b subunits may be explained by CaVβ2b subunit oligomers with different modulation of the channel activity. An existence of CaVβ subunit oligomers may lead to more comprehensive mechanisms for CaVβ subunit displacement from CaV channels but it does not change the conclusions of our work.

Limitations and perspectives

Dynamic regulation of CaV channels by CaVβ subunits allows modification of the channel gating. Furthermore, CaV channels can be regulated by other proteins via their interaction with CaVβ subunits, e.g., by G-protein βγ subunits, Ras-related RGK GTPases, many types of kinases, and bestrophin-1 (2). Moreover, by preventing ubiquitination or interacting with dynamin, CaVβ subunits control degradation and internalization of CaV channels (36–38). Akt-dependent phosphorylation of CaVβ2 subunits prevents proteolysis of CaV channels, importantly, the phosphorylation site being conserved only in CaVβ2 isoforms (39,40). The number of proteins regulating CaV channels will continue to grow: comprehensive proteomic studies identified 207 proteins that interact with and form a nanoenvironment of CaV2-CaVβ channel complexes (41). Results of our studies implicate that the subunit composition of CaV channels can be changed on a physiological timescale, allowing rapid adjustment to particular cellular requirements.

In future experiments on the competition between CaVβ subunits, it would be interesting to modify the strength of CaVα1-CaVβ interaction, e.g., by site-directed mutagenesis of ABP (42). However, if this will result in an even faster exchange of CaVβ subunits, this might not be resolved statistically by the segmentation of the open-probability diaries. The statistical resolution could perhaps be improved by choosing CaVβ subunits with more distinct gating properties. Nevertheless, here, we preferred to use CaVβ2b instead of CaVβ2a subunits, which also strongly enhances open probability and strongly inhibits voltage-dependent inactivation (13,14,43), because palmitoylation of CaVβ2a leads to its tethering to the cell membrane and, as a result, CaVβ2a subunits can interact with CaVα1 bypassing binding to AID (18). Alternatively, one could think to increase open probability applying channel agonists, e.g., (S)-BayK 8644. On the other hand, this can reduce the isoform difference in gating modulation by CaVβ subunits (13). Another source for methodological improvement would be complete elimination of endogenous subunits, either by choosing a different cell line, or RNA silencing strategies. Furthermore, modifications of the pulse protocol maybe used to address whether the switching kinetics are inherently voltage-dependent.

We frankly admit that the complex natural proteomic environment of CaV channels (41) will not be fully reconstituted within any heterologous (over-)expression system. Yet, we believe that our experimental approach, followed by careful tuning of the analytical strategy to monitor single-channel behavior in real-time, will pave the way to address the subunit interaction dynamics in intact native cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bernadette Henning for excellent help on performing qRT-PCR experiments and Prof. Dr. Lehmann-Horn for providing α2δ-1 plasmid. E.K. is grateful for the financial support from Professorinnen-Programm of the University of Cologne. This work was supported by the Center for Molecular Medicine Cologne (CMMC A4 to S.H.).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Catterall W.A. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buraei Z., Yang J. The β subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol. Rev. 2010;90:1461–1506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pragnell M., De Waard M., Campbell K.P. Calcium channel β-subunit binds to a conserved motif in the I-II cytoplasmic linker of the α1-subunit. Nature. 1994;368:67–70. doi: 10.1038/368067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Waard M., Witcher D.R., Campbell K.P. Properties of the α1-β anchoring site in voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:12056–12064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y.H., Li M.H., Yang J. Structural basis of the α1-β subunit interaction of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Nature. 2004;429:675–680. doi: 10.1038/nature02641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Opatowsky Y., Chen C.C., Hirsch J.A. Structural analysis of the voltage-dependent calcium channel β-subunit functional core and its complex with the α1 interaction domain. Neuron. 2004;42:387–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Petegem F., Clark K.A., Minor D.L., Jr. Structure of a complex between a voltage-gated calcium channel β-subunit and an α-subunit domain. Nature. 2004;429:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nature02588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi H., Hara M., Varadi G. Multiple modulation pathways of calcium channel activity by a β-subunit. Direct evidence of β-subunit participation in membrane trafficking of the α1C subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19348–19356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García R., Carrillo E., Sánchez J.A. The β1a subunit regulates the functional properties of adult frog and mouse L-type Ca2+ channels of skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2002;545:407–419. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.027433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y., Chen Y.H., Yang J. Origin of the voltage dependence of G-protein regulation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:14176–14188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1350-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hidalgo P., Gonzalez-Gutierrez G., Neely A. The α1-β-subunit interaction that modulates calcium channel activity is reversible and requires a competent α-interaction domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:24104–24110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hullin R., Khan I.F., Herzig S. Cardiac L-type calcium channel β-subunits expressed in human heart have differential effects on single channel characteristics. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21623–21630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herzig S., Khan I.F., Hullin R. Mechanism of Cav1.2 channel modulation by the amino terminus of cardiac β2-subunits. FASEB J. 2007;21:1527–1538. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7377com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hullin R., Matthes J., Herzig S. Increased expression of the auxiliary β2-subunit of ventricular L-type Ca2+ channels leads to single-channel activity characteristic of heart failure. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jangsangthong W., Kuzmenkina E., Herzig S. Inactivation of L-type calcium channels is determined by the length of the N terminus of mutant β1 subunits. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:399–411. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0738-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuzmenkina E.V., Heyes C.D., Nienhaus G.U. Single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer study of protein dynamics under denaturing conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15471–15476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507728102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Efron B. Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann. Stat. 1979;7:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leroy J., Richards M.W., Dolphin A.C. Interaction via a key tryptophan in the I-II linker of N-type calcium channels is required for β1 but not for palmitoylated β2, implicating an additional binding site in the regulation of channel voltage-dependent properties. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6984–6996. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1137-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hess P., Lansman J.B., Tsien R.W. Different modes of Ca channel gating behavior favored by dihydropyridine Ca agonists and antagonists. Nature. 1984;311:538–544. doi: 10.1038/311538a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yue D.T., Herzig S., Marban E. Beta-adrenergic stimulation of calcium channels occurs by potentiation of high-activity gating modes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:753–757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costantin J., Noceti F., Stefani E. Facilitation by the β2a subunit of pore openings in cardiac Ca2+ channels. J. Physiol. 1998;507:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.093bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dzhura I., Neely A. Differential modulation of cardiac Ca2+ channel gating by β-subunits. Biophys. J. 2003;85:274–289. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74473-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luvisetto S., Fellin T., Pietrobon D. Modal gating of human CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) calcium channels: I. The slow and the fast gating modes and their modulation by β subunits. J. Gen. Physiol. 2004;124:445–461. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez-Gutierrez G., Miranda-Laferte E., Neely A. Mutations of nonconserved residues within the calcium channel α1-interaction domain inhibit β-subunit potentiation. J. Gen. Physiol. 2008;132:383–395. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herzig S., Patil P., Yue D.T. Mechanisms of β-adrenergic stimulation of cardiac Ca2+ channels revealed by discrete-time Markov analysis of slow gating. Biophys. J. 1993;65:1599–1612. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81199-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geib S., Sandoz G., de Waard M. Use of a purified and functional recombinant calcium-channel β4 subunit in surface-plasmon resonance studies. Biochem. J. 2002;364:285–292. doi: 10.1042/bj3640285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cantí C., Davies A., Dolphin A.C. Evidence for two concentration-dependent processes for β-subunit effects on α1B calcium channels. Biophys. J. 2001;81:1439–1451. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75799-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tareilus E., Roux M., Birnbaumer L. A Xenopus oocyte β subunit: evidence for a role in the assembly/expression of voltage-gated calcium channels that is separate from its role as a regulatory subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:1703–1708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bichet D., Lecomte C., De Waard M. Reversibility of the Ca2+ channel α1-β subunit interaction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;277:729–735. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hohaus A., Poteser M., Groschner K. Modulation of the smooth-muscle L-type Ca2+ channel α1 subunit (α1C-b) by the β2a subunit: a peptide which inhibits binding of β to the I-II linker of α1 induces functional uncoupling. Biochem. J. 2000;348:657–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker D., Bichet D., De Waard M. A β4 isoform-specific interaction site in the carboxyl-terminal region of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel α1A subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2361–2367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker D., Bichet D., De Waard M. A new β subtype-specific interaction in α1A subunit controls P/Q-type Ca2+ channel activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:12383–12390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maltez J.M., Nunziato D.A., Pitt G.S. Essential CaVβ modulatory properties are AID-independent. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:372–377. doi: 10.1038/nsmb909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang R., Dzhura I., Anderson M.E. A dynamic α-β inter-subunit agonist signaling complex is a novel feedback mechanism for regulating L-type Ca2+ channel opening. FASEB J. 2005;19:1573–1575. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3283fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lao Q.Z., Kobrinsky E., Soldatov N.M. Oligomerization of Cavβ subunits is an essential correlate of Ca2+ channel activity. FASEB J. 2010;24:5013–5023. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-165381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miranda-Laferte E., Gonzalez-Gutierrez G., Hidalgo P. Homodimerization of the Src homology 3 domain of the calcium channel β-subunit drives dynamin-dependent endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:22203–22210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.201871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altier C., Garcia-Caballero A., Zamponi G.W. The Cavβ subunit prevents RFP2-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of L-type channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:173–180. doi: 10.1038/nn.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waithe D., Ferron L., Dolphin A.C. Beta-subunits promote the expression of CaV2.2 channels by reducing their proteasomal degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:9598–9611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.195909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viard P., Butcher A.J., Dolphin A.C. PI3K promotes voltage-dependent calcium channel trafficking to the plasma membrane. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:939–946. doi: 10.1038/nn1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Catalucci D., Zhang D.H., Condorelli G. Akt regulates L-type Ca2+ channel activity by modulating Cavα1 protein stability. J. Cell Biol. 2009;184:923–933. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Müller C.S., Haupt A., Schulte U. Quantitative proteomics of the Cav2 channel nano-environments in the mammalian brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14950–14957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005940107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Petegem F., Duderstadt K.E., Minor D.L., Jr. Alanine-scanning mutagenesis defines a conserved energetic hotspot in the CaVα1 AID-CaVβ interaction site that is critical for channel modulation. Structure. 2008;16:280–294. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colecraft H.M., Alseikhan B., Yue D.T. Novel functional properties of Ca2+ channel β subunits revealed by their expression in adult rat heart cells. J. Physiol. 2002;541:435–452. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schleithoff L., Mehrke G., Lehmann-Horn F. Genomic structure and functional expression of a human α2/δ calcium channel subunit gene (CACNA2) Genomics. 1999;61:201–209. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schultz D., Mikala G., Schwartz A. Cloning, chromosomal localization, and functional expression of the α1 subunit of the L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel from normal human heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:6228–6232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.