Abstract

MHC Class II tetramers have emerged as an important tool for characterization of the specificity and phenotype of CD4 T cell immune responses, useful in a large variety of disease and vaccine studies. Issues of specific T cell frequency, biodistribution, and avidity, coupled with the large genetic diversity of potential class II restriction elements, require targeted experimental design. Translational opportunities for immune disease monitoring are driving rapid development of HLA class II tetramer use in clinical applications, together with innovations in tetramer production and epitope discovery.

Keywords: T cells, immunomonitoring, MHC tetramers, class II molecules, HLA

Introduction

The concept of using soluble labeled ligands to detect cell surface receptors is a standard approach for understanding molecular specificity and function. Only in the last 15 years, however, has this general strategy been successfully applied to the analysis of antigen-specific T cells through the use of soluble MHC-peptide ligands that engage the αβTCR. Originally developed for MHC class I recognition in the context of CD8 T cells (1,2), over the last decade similar approaches have been successfully used for MHC class II recognition in the context of CD4 T cells for a wide variety of antigens. From this experience, it is now evident that interrogating CD4 T cells using soluble tetramers has matured into a robust technology, notably useful in numerous translational and clinical contexts. However, several constraints that limit their use are also now understood. In this Brief Review, key issues governing CD4 T cell identification by MHC class II tetramers are discussed, and examples from human immune monitoring studies illustrate the lessons learned.

Adding specificity to the T cell flow cytometry toolkit

Peptide-MHC (pMHC) class II multimers display an antigenic peptide in the class II binding groove, functioning as a surrogate for recognition events that occur as part of the T cell interaction with antigen-presenting cells. Various methods for displaying peptide-MHC class II molecules have been successfully used, ranging from monomeric pMHC bound to solid substrates or soluble in solution, to higher order multimers complexed with various scaffold molecules. The most prevalent form of multimer in use today consists of biotin-labeled pMHC displayed on streptavidin molecules, forming ostensibly tetravalent complexes; hence, the common use of the term “tetramers” for this detection method.

Tetramer assays are widely used for single-cell phenotyping and enumeration, and offer an important advantage over other methods, such as ELISPOT and single-cell PCR, by enabling the recovery and further study of sorted cells based on fluorescent tetramer binding in flow cytometry. As a cytometry-based application, tetramers also provide the prospect of ease of use and short assay time, analogous to antibody-based flow cytometry studies. The major limitation to their use is the requirement to have some knowledge of the specific peptide-MHC components involved in the recognition events being studied, as these are necessary to construct the tetramer reagents. A corollary to this element of MHC restriction is the consideration that humans have very diverse HLA class II molecules, so that random sampling or clinical monitoring studies may require the use of many different tetramers to include a broad representation of the population.

Straightforward solutions exist for both of these limitations—HLA diversity and epitope identification—by making the investment necessary to produce a universal set of class II tetramers for most HLA alleles, and by utilizing functional selection of relevant epitopes as a criterion for study design. With these advances, discussed below, there has been a rapid expansion of studies utilizing tetramers to study CD4 T cell response to vaccines, allergens, and a variety of antigens associated with autoimmune diseases. There has also been an improved understanding surrounding the potential use of tetramers, because as the technological problems have been largely solved, there is now realization of some important biological barriers associated with interrogating the specific TCR-tetramer interaction.

Rare CD4 T cell detection using class II pMHC tetramers

A major challenge for studies using HLA class II tetramers is the low frequency of antigen-specific CD4 T cells in peripheral blood. Highly boosted responses, such as tetanus-specific or influenza-specific CD4 T cells after immunization, display transient levels of antigen-specific cells in the 1:1000-1:20,000 range; specific memory T cells without recent boosting are more often found in the 1:20,000-1:100,000 range; and rare responses or autoantigen-specific responder cells are detectable in the 1:100,000-1:1 million range. Naïve T cell frequencies to particular pMHC are also around 1:200,000-1:1 million. Due to these low cell frequencies, the first generation of tetramer-based immunoassays utilized in vitro activation and/or expansion to enable T cell detection (3), somewhat analogous to the historically used techniques of limiting dilution proliferation assays and ELISpot analysis. Of course, a major problem with such an approach was the potential for phenotypic changes introduced by in vitro manipulation, and these studies were therefore limited primarily to the estimates of cell frequency and specificity.

Current second-generation tetramer assays avoid the use of in vitro expansion, and are either based on single-cell capture technology (4-6) or on direct flow cytometry staining analysis (7-10). In the latter, stringent “dumping” criteria and enrichment with magnetic bead trapping procedures are used to remove cells that lack tetramer specificity, enriching the antigen-specific population as much as 10,000-fold, allowing for detection of rare events, e.g., 10 tetramer-binding T cells from 20 cc of peripheral blood. In addition, multiparameter flow cytometry analysis using a variety of mAbs simultaneously with tetramer assays allows for direct phenotyping of the antigen-specific cells, a major advance towards discriminating T cell functional subsets directed to a single antigen.

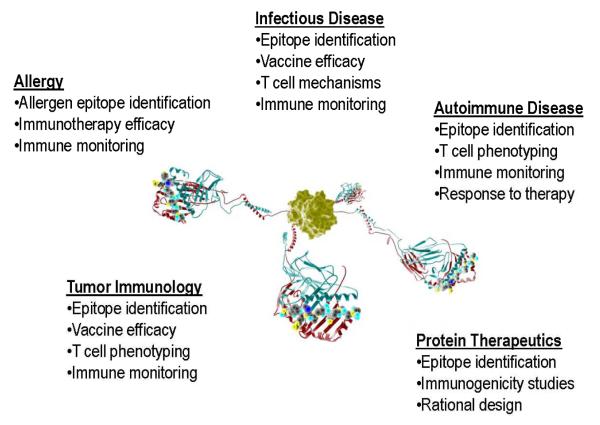

HLA class II tetramers are now widely used in studies of pathogen immunity and vaccine development, in evaluation of anti-tumor responses, in allergy monitoring and desensitization studies, and in autoimmunity (Figure 1). Examples of each are summarized below and illustrate particular issues faced in these different applications.

Figure 1. Molecular design schematic of a class II tetramer molecule.

illustrating four pMHC domains tethered to a central streptavidin molecule through flexible linker sequences and leucine zipper motifs to provide structural stability. Some of the major areas of tetramer analysis in human disease applications are listed.

Monitoring immunity to infectious pathogens

Class II tetramers have been utilized for analysis of a wide variety of human CD4 T cell responses to pathogens, including influenza A, Borrelia, EBV, CMV, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, HTLV-1, hepatitis C, anthrax, SARS, HPV, and HIV (3,7,11-30). Antigen-specific T cells are detected in peripheral blood, with a very broad range of frequency, depending on prior antigen exposure, vaccination history, and timing of immunization. The most significant limitation for these studies is simply the large number of potential epitopes present in complex organisms; not only are there multiple potential protein targets within each pathogen, but a huge number of processed and presented peptides are potentially targets for CD4 T cell recognition. For example, within the protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis, multiple epitopes are present, and, as expected, the dominance of each epitope varies depending on the HLA genotype of the individual subject (23). Selection of tetramers for studies of the T cell response to anthrax or similarly complex agents therefore involves matching the HLA class II genotype of each subject with appropriately tailored pMHC tetramers (31). On the other hand, occasionally there are immunodominant epitopes from pathogens that bind promiscuously to multiple HLA class II molecules. When this occurs, production and utilization of appropriate pMHC tetramers becomes straightforward. For example, the hemagglutinin protein of influenza A H1N1 contains a peptide epitope (amino acids 306-319) that binds to at least five common human class II molecules, and is recognized by T cells in each case. Most people, through either natural exposure or periodic flu vaccination, contain peripheral CD4 T cells recognizing this epitope (14). A similar strategy has been adopted to search for conserved epitopes in pandemic strain H5N1, after vaccination (32). T cells recognizing additional influenza epitopes can be found simultaneously in the same blood samples using other tetramers, but appear to be more specific to a given individual (12,33). An interesting exception was seen in tetramer analysis with pMHC corresponding to the H5N1 influenza strain hemagglutinin, with cross-reactivity from pre-existing immunity to other influenza strains, allowing detection of T cells reactive to H5N1, even in the absence of direct exposure to this strain (24).

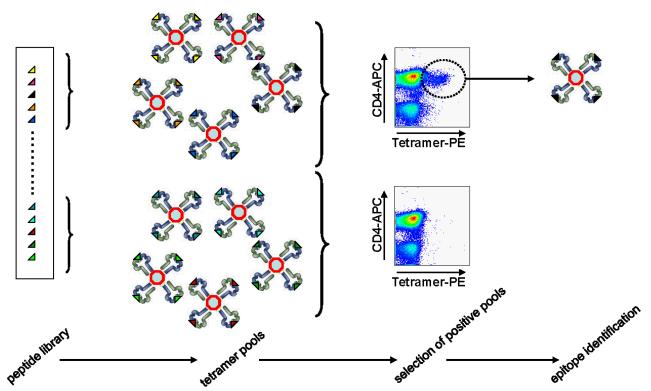

With hundreds of potential peptide epitopes to choose from, selecting pMHC tetramers for studying infectious pathogens or vaccines is challenging. Traditional methods involving functional testing of individual peptides from large libraries are laborious, and, when based on a particular functional parameter (e.g., interferon ELISPOT analysis), may omit epitopes that are important for other T cell subsets or lineages. To address this issue, an unbiased platform has been developed for a tetramer-binding and flow cytometry screening method that directly determines suitable pMHC tetramers. This technique, called tetramer-guided epitope mapping (TGEM), involves the display of large peptide libraries loaded into HLA class II molecules (Figure 2). Pools of tetramers are used to probe the T cell population of interest, and positive tetramer binding, assessed by flow cytometry, is deconvoluted in a second flow cytometry step into individual pMHC targets (34,35). This approach has been applied to a wide variety of infectious agents, with epitope identification information deposited in the NIAID-sponsored archive, IEDB.org.

Figure 2. Epitope identification utilizing a tetramer-guided mapping strategy.

Large peptide libraries, separated into sets of pooled sequences, are loaded into the binding groove of recombinant class II molecules and assembled into tetramers. Direct flow cytometry analysis of T cell populations identifies peptides containing actual epitopes representative of the natural immune response.

Allergen tetramers: a tool for improved immunotherapy?

Translation from a laboratory tool to a clinically useful biomarker is a difficult transition for any technology, but in the area of allergy desensitization therapy human class II tetramers have their most immediate translational potential. Similar to the study of infectious pathogens, tetramer development for allergens is complicated by the diversity and number of potential CD4 T cell epitopes. However, for many of the major allergic disorders, including allergies to foods, pollen, and dander, there is a large body of knowledge narrowing the field of target allergen proteins. The TGEM technique has been applied to several of these, resulting in the identification of epitopes and tetramers suitable for analysis of peripheral T cell recognition to major allergens (10,16,26,29). In allergic individuals, the frequency of tetramer-binding CD4 T cells in peripheral blood, particularly during periods of allergen exposure, is suitably high, allowing direct detection by flow cytometry after tetramer binding. In a recent study by Wambre, et al., multiparameter flow analysis documented progressive shifts in cell surface marker profiles associated with T cell deviation during subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy (10). Current clinical desensitization protocols utilize allergen extracts, require very long-term administration, and carry significant risk of adverse allergic response, making it attractive to consider using tetramer-based immune monitoring in this context. Also, since one approach to improve allergy immunotherapy is to utilize peptides instead of allergen extracts (19,36), the TGEM technique and tetramer monitoring may help identify appropriate peptide epitopes for use, particularly if stratification based on HLA genotype is needed.

Tetramer profiling of low avidity T cells in autoimmunity.

Human class II pMHC tetramers containing autoantigenic specificities have been used to study T cell responses in a variety of diseases, including type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, pemphigus vulgaris, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and uveitis (37-47). These studies have highlighted a fundamental point, namely, that the avidity of the TCR interaction with its pMHC target is influenced by selection against high affinity self-antigen recognition. Unlike tetramer analyses in the infectious pathogen and allergen studies cited above, in which most of the responding T cells have a high avidity binding to appropriate pMHC tetramers, tetramer binding to peripheral T cells in the context of autoimmunity displays a much wider spectrum of relative strength of interaction. In addition, the frequency of autoreactive CD4 T cells specific for a particular pMHC self-antigen complex is quite low in peripheral blood, often less than five per million lymphocytes, requiring large sample volumes and careful handling for reliable detection.

The most complete autoimmunity studies have been performed in the context of type 1 diabetes (T1D), a disease in which several major autoantigens are well characterized. Class II tetramers specific for the T1D autoantigens glutamate dehydrogenase (GAD), proinsulin, IA-2, and ZnT8 have all been used to evaluate T cell frequencies in peripheral blood. Findings from these studies support the concept that the autoreactive repertoire matures during disease progression: Firstly, normal individuals, as well as T1D subjects, have low but detectable levels of circulating tetramer-binding CD4 cells. However, these display markers of naïve lymphocytes in the former group, whereas they are predominantly memory phenotype in the latter, presumably reflect a history of prior activation in vivo. Secondly, while some high avidity autoreactive T cells are present, and can be expanded in culture, the population of tetramer-binding cells contains both low and high avidity TCR for the autoantigen pMHC. By taking advantage of the unique genetics of human T1D, in which a polymorphism in the proinsulin promoter region controls levels of thymic expression (48,49), Durinovic-Belló et al. demonstrated that the strength of tetramer binding to proinsulin-specific T cells correlated with this genotype, directly linking thymic antigen expression with avidity selection for the CD4 repertoire (44). Thirdly, when T1D patients undergo pancreas transplantation, they essentially receive an immunological challenge with islet autoantigens, in addition to the alloreactivity associated with an organ transplant. Tetramer analysis of such subjects, followed for several years after transplantation, has documented both the expansion of autoantigen pMHC tetramer-binding CD4 T cells, and more remarkably the persistence of unique clonotypic TCR sequences within this population, indicating a recurrence of memory responses from a pre-existing autoreactive repertoire (50,51).

The low frequency and low avidity of T cells specific for autoantigens presents special technical challenges, but several creative approaches have shown promise for improving tetramer detection strategies. In a recent study of subjects with rheumatoid arthritis, class II tetramers were used to test an intriguing mechanistic hypothesis, namely, that post-translational modification of peptide epitopes creates neoantigenic specificities targeted in the disease setting (52). James, et al., also prepared HLA class II tetramers containing citrulline-modified peptides based on fibrinogen protein sequences found in joint tissue, and documented the presence of T cells that bound these tetramers and responded to the corresponding autoantigen (45). In celiac disease, where there is also post-translational modification of target antigens, class II tetramers composed of gliadin pMHC complexes were shown to bind peripheral CD4 T cells, but these cells were only detectable when the subjects consumed gluten-containing bread for three days (53). This finding strongly suggests that mobilization of the antigen-specific cells from tissue to blood was necessary for visualization, and may provide a generalizable strategy, involving antigen challenge, for improving the detection threshold for rare autoreactive cells.

A related issue, particularly relevant to the analysis of low avidity T cell responses in autoimmunity, is the definition of a precise peptide binding register for docking within the class II molecule. The presence of more than one binding register within long peptides generated during antigen processing can result in presentation of pMHC ligands to distinct TCR, with potentially different roles in selection and autoreactivity (54,55).

Tetramer studies of tumor antigens are similar to the autoantigen approach, with an opportunity to help inform both disease mechanism and therapy. Although most tumor antigens are self- or modified self-antigens, intentional immunization with these antigens is conducted for therapeutic benefit. For example, class II tetramer studies in patients with malignant melanoma after experimental vaccine therapies have documented evidence of immunogenicity, measured the effects of adjuvant on T cell lineage, and have been used to evaluate shifts in T cell subsets (56-59). Indeed, since the pMHC complex is itself a surrogate for antigen recognition, it is feasible that tetramers can potentially be considered for therapeutic expansion of antigen-specific effector T cells (60).

Variations on the tetramer theme

Biophysical studies and off-rate analysis suggest that multivalent binding of pMHC to the TCR is essential for successful tetramer imaging of antigen-specific T cells. Monomeric and dimeric forms of pMHC are much less efficient than tetramers (61), while higher order multimers, such as octomers, decamers, or pMHC-coated beads, are all successful reagents, generally comparable to tetramers. A caveat to this interpretation, however, is that streptavidin aggregates during storage, so that experiments ostensibly using tetrameric forms of pMHC linked to streptavidin may in fact be using higher order complexes, at least in part.

A variety of methods has been successfully used to manufacture pMHC class II tetramers, with expression of HLA class II molecules either “empty”—without intentional loading of peptide into the class II antigen-binding groove; “loaded”—in which the expression system is coupled to a facilitated peptide-loading process, resulting in production of complete pMHC; or “covalent”— in which an MHC expression vector is engineered to cotranslationally express the peptide, with a flexible and/or removable linker sequence allowing for 1:1 stoichiometry of peptide:MHC and directed peptide binding into the class II-binding groove. Expression systems have included mammalian, insect cell, or bacterial sources (62). There are advantages to each system, depending on the intended type of tetramer assay planned. For example, covalent pMHC are well suited for consistent production systems and for situations where a small number of specific peptide-MHC combinations are used. They are not well suited to screening assays involving hundreds of different potential peptide antigens, and neoepitope exposure due to the presence of linker sequence or a too-stringent binding register is a potential concern. An important use of non-covalent peptide-loaded pMHC production systems is the ability to assess many different tetramer-binding specificities at the same time. This has been exploited in the TGEM technique described above, in which large mixtures of peptides, most commonly representing the entire protein sequence of potential antigenic targets, are interrogated to determine which peptides within the mixture contain actual T cell epitopes.

Due to the high specificity and sensitivity of TCR recognition for pMHC, tetramer-binding studies can also be designed to identify unconventional antigenic epitopes. For example, many protein therapeutics that are administered to patients are potentially immunogenic. Analysis of the T cell response in these cases, using tetramers containing pMHC specificities from the therapeutic molecule, can readily identify the specific epitopes that trigger immunogenicity, as illustrated in a study of Factor VIII administration in hemophilia A (63).

Examples of technical variations that are designed to improve the efficiency of tetramer production include co-expression with chaperone proteins (64), biotinylation of the expressed MHC molecule during synthesis (65), modifications of peptide linkers used to dock covalent peptides in the co-expressed MHC groove (66), or the use of cleavable CLIP peptides (7), which take advantage of the natural role of invariant chain residues (CLIP) that are a functional intermediate in loading peptides into class II molecules. One of the most intriguing innovations is the use of entire libraries of class II pMHC molecules plated on arrays designed to capture antigen-specific T cells (67), similar to earlier studies using class I tetramers (68).

Conclusions

After more than a decade of experience, class II tetramer analysis has become a regular component of T cell specificity studies across the entire landscape of immunological investigation. A decision to include class II tetramer studies, and how to use them, however, is not as routine as selecting antibodies for flow cytometry. There are four key issues that should be considered and used as the basis for experimental choice:

First, what is the anticipated frequency of CD4 T cells recognizing immunodominant epitopes in the system? If there is no prior evidence for immunodominance, and no information from previous T cell assays regarding prevalence, then it is a challenge to select a particular pMHC tetramer that will be representative of the T cell response profile. Either multiple different pMHC can be selected, individually or as a mixed tetramer pool, or alternatively a technique such as TGEM can be used in pilot studies to directly determine the appropriate pMHC combinations.

Second, what is the likely biodistribution of CD4 T cells of interest? In cases such as celiac disease, as described above, mobilization of the antigen-specific T cells into the bloodstream was accomplished by antigen challenge. This may have general applicability, supported by the observations in T1D that tetramer-positive cells are much higher after pancreas transplantation or after GAD immunization (H Reijonen, personal communication), compared with unimmunized diabetic subjects. If the antigen-specific cells are at tissue sites of interest, more complex biopsy and in situ histochemistry techniques are needed.

Third, avidity matters. Unlike foreign antigen responses in vaccine or allergy studies, self-antigen responses in autoimmunity or tumor immunology reflect a diverse spectrum of TCR avidity for pMHC complexes, including interactions that are near or below the threshold for robust tetramer-binding detection. If the experimental system requires detection of such low avidity interactions, methods to amplify the tetramer binding signals may be helpful. Alternatively, T cell activation triggered by tetramer binding can be used as a surrogate measure, with a threshold lower than conventional flow cytometry detection (62,69).

Fourth, how genetically diverse is the population being studied? The requirement for pMHC cognate recognition by the CD4 T cell dictates that at least one of the class II molecules in each subject corresponds to the HLA molecule used for the tetramer. For populations that are highly enriched for particular HLA class II genes, such as in type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, or celiac disease, this is not a limiting factor. For population-based vaccine studies or allergy monitoring trials, however, a large number of tetramers is needed, or alternatively subjects are pre-selected based on HLA genotype. Either way, a significant complexity is added to the study. HLA class II tetramers for 25 of the most common genotypes are now available, so this is not an insurmountable barrier, if taken into account in experimental design [http://www.benaroyaresearch.org/our-research/core-resources/tetramer-core-laboratory].

Acknowledgments

The work of numerous colleagues at the Benaroya Research Institute and elsewhere, who have pioneered the class II tetramer technology, is gratefully acknowledged, and any omissions from the citation list, limited by space, are inadvertent.

Footnotes

Work in the author’s laboratory cited in this article has been supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Reference List

- 1.Altman JD, Moss PAH, Goulder PJR, Barouch DH, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Bell JI, McMichael AJ, Davis MM. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274:94–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lebowitz MS, O’Herrin SM, Hamad AR, Fahmy T, Marguet D, Barnes NC, Pardoll D, Bieler JG, Schneck JP. Soluble, high-affinity dimers of T-cell receptors and class II major histocompatibility complexes: biochemical probes for analysis and modulation of immune responses. Cell Immunol. 1999;192:175–184. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novak EJ, Liu AW, Nepom GT, Kwok WW. MHC class II tetramers identify peptide-specific human CD4(+) T cells proliferating in response to influenza A antigen. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:R63–R67. doi: 10.1172/JCI8476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron TO, Cohen GB, Islam SA, Stern LJ. Examination of the highly diverse CD4(+) T-cell repertoire directed against an influenza peptide: a step towards TCR proteomics. Immunogenet. 2002;54:611–620. doi: 10.1007/s00251-002-0508-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newell EW, Klein LO, Yu W, Davis MM. Simultaneous detection of many T-cell specificities using combinatorial tetramer staining. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:497–499. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song Q, Han Q, Bradshaw EM, Kent SC, Raddassi K, Nilsson B, Nepom GT, Hafler DA, Love JC. On-chip activation and subsequent detection of individual antigen-specific T cells. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:473–477. doi: 10.1021/ac9024363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day CL, Seth NP, Lucas M, Appel H, Gauthier L, Lauer GM, Robbins GK, Szczepiorkowski ZM, Casson DR, Chung RT, Bell S, Harcourt G, Walker BD, Klenerman P, Wucherpfennig KW. Ex vivo analysis of human memory CD4 T cells specific for hepatitis C virus using MHC class II tetramers. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:831–842. doi: 10.1172/JCI18509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scriba TJ, Purbhoo M, Day CL, Robinson N, Fidler S, Fox J, Weber JN, Klenerman P, Sewell AK, Phillips RE. Ultrasensitive detection and phenotyping of CD4+ T cells with optimized HLA class II tetramer staining. J. Immunol. 2005;175:6334–6343. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu H, J H, Moon J, Takada K, Pepper M, Molitor JA, Schacker TW, Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Jenkins MK. Positive selection optimizes the number and function of MHCII-restricted CD4+ T cell clones in the naive polyclonal repertoire. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:11241–11245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902015106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wambre E, DeLong JH, James EA, Lafond RE, Robinson D, Kwok WW. Differentiation stage determines pathologic and protective allergen-specific CD4(+) T-cell outcomes during specific immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer AL, Trollmo C, Crawford F, Marrack P, Steere AC, Huber BT, Kappler J, Hafler DA. Direct enumeration of Borrelia-reactive CD4 T cells ex vivo by using MHC class II tetramers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:11433–11438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190335897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danke NA, Kwok WW. HLA class II-restricted CD4+ T cell responses directed against influenza viral antigens postinfluenza vaccination. J. Immunol. 2003;171:3163–3169. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucas M, Day CL, Wyer JR, Cunliffe SL, Loughry A, McMichael AJ, Klenerman P. Ex vivo phenotype and frequency of influenza virus-specific CD4 memory T cells. J. Virol. 2004;78:7284–7287. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.7284-7287.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye M, Kasey S, Khurana S, Nguyen NT, Schubert S, Nugent CT, Kuus-Reichel K, Hampl J. MHC class II tetramers containing influenza hemagglutinin and EBV EBNA1 epitopes detect reliably specific CD4(+) T cells in healthy volunteers. Hum. Immunol. 2004;65:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bronke C, Palmer NM, Westerlaken GH, Toebes M, van Schijndel GM, Purwaha V, van Meijgaarden KE, Schumacher TN, van BD, Tesselaar K, Geluk A. Direct ex vivo detection of HLA-DR3-restricted cytomegalovirus- and Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD4+ T cells. Hum. Immunol. 2005;66:950–961. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macaubas C, Wahlstrom J, Galvao da Silva AP, Forsthuber TG, Sonderstrup G, Kwok WW, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Allergen-specific MHC class II tetramer+ cells are detectable in allergic, but not in nonallergic, individuals. J. Immunol. 2006;176:5069–5077. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulsenheimer A, Lucas M, Seth NP, Tilman GJ, Gruener NH, Loughry A, Pape GR, Wucherpfennig KW, Diepolder HM, Klenerman P. Transient immunological control during acute hepatitis C virus infection: ex vivo analysis of helper T-cell responses. J. Viral Hepat. 2006;13:708–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohn H, Kortsik C, Zehbe I, Hitzler WE, Kayser K, Freitag K, Neukirch C, Andersen P, Doherty TM, Maeurer M. MHC class II tetramer guided detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 2007;65:467–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinnunen T, Jutila K, Kwok WW, Rytkonen-Nissinen M, Immonen A, Saarelainen S, Narvanen A, Taivainen A, Virtanen T. Potential of an altered peptide ligand of lipocalin allergen Bos d 2 for peptide immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;119:965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laughlin EM, Miller JD, James E, Fillos D, Ibegbu CC, Mittler RS, Akondy R, Kwok W, Ahmed R, Nepom G. Antigen-specific CD4+ T cells recognize epitopes of protective antigen following vaccination with an anthrax vaccine. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:1852–1860. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01814-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nose H, Kubota R, Seth NP, Goon PK, Tanaka Y, Izumo S, Usuku K, Ohara Y, Wucherpfennig KW, Bangham CR, Osame M, Saito M. Ex vivo analysis of human T lymphotropic virus type 1-specific CD4+ cells by use of a major histocompatibility complex class II tetramer composed of a neurological disease-susceptibility allele and its immunodominant peptide. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196:1761–1772. doi: 10.1086/522966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ebinuma H, Nakamoto N, Li Y, Price DA, Gostick E, Levine BL, Tobias J, Kwok WW, Chang KM. Identification and in vitro expansion of functional antigen-specific CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in hepatitis C virus infection. J. Virol. 2008;82:5043–5053. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01548-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwok WW, Yang J, James E, Bui J, Huston L, Wiesen AR, Roti M. The anthrax vaccine adsorbed vaccine generates protective antigen (PA)-Specific CD4+ T cells with a phenotype distinct from that of naive PA T cells. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:4538–4545. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00324-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roti M, Yang J, Berger D, Huston L, James EA, Kwok WW. Healthy human subjects have CD4+ T cells directed against H5N1 influenza virus. J. Immunol. 2008;180:1758–1768. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, James E, Roti M, Huston L, Gebe JA, Kwok WW. Searching immunodominant epitopes prior to epidemic: HLA class II-restricted SARS-CoV spike protein epitopes in unexposed individuals. Int. Immunol. 2009;21:63–71. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinnunen T, Nieminen A, Kwok WW, Narvanen A, Rytkonen-Nissinen M, Saarelainen S, Taivainen A, Virtanen T. Allergen-specific naive and memory CD4+ T cells exhibit functional and phenotypic differences between individuals with or without allergy. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010;40:2460–2469. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vingert B, Perez-Patrigeon S, Jeannin P, Lambotte O, Boufassa F, Lemaitre F, Kwok WW, Theodorou I, Delfraissy JF, Theze J, Chakrabarti LA. HIV controller CD4+ T cells respond to minimal amounts of Gag antigen due to high TCR avidity. PLoS. Pathog. 2010;6:e1000780. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cusick MF, Yang M, Gill JC, Eckels DD. Naturally occurring CD4+ T-cell epitope variants act as altered peptide ligands leading to impaired helper T-cell responses in hepatitis C virus infection. Hum. Immunol. 2011;72:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeLong JH, Simpson KH, Wambre E, James EA, Robinson D, Kwok WW. Ara h 1-reactive T cells in individuals with peanut allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;127:1211–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James EA, DeVoti JA, Rosenthal DW, Hatam LJ, Steinberg BM, Abramson AL, Kwok WW, Bonagura VR. Papillomavirus-specific CD4+ T cells exhibit reduced STAT-5 signaling and altered cytokine profiles in patients with recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. J. Immunol. 2011;186:6633–6640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James EA, Bui J, Berger D, Huston L, Roti M, Kwok WW. Tetramer-guided epitope mapping reveals broad, individualized repertoires of tetanus toxin-specific CD4+ T cells and suggests HLA-based differences in epitope recognition. Int. Immunol. 2007;19:1291–1301. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang SF, Yao L, Liu SJ, Chong P, Liu WT, Chen YM, Huang JC. Identifying conserved DR1501-restricted CD4(+) T-cell epitopes in avian H5N1 hemagglutinin proteins. Viral Immunol. 2010;23:585–593. doi: 10.1089/vim.2010.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang J, James EA, Huston L, Danke NA, Liu AW, Kwok WW. Multiplex mapping of CD4 T cell epitopes using class II tetramers. Clin. Immunol. 2006;120:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novak EJ, Liu AW, Gebe JA, Falk B, Nepom GT, Koelle DM, Kwok WW. Tetramer guided epitope mapping: rapid identification and characterization of immunodominant CD4+ T cell epitopes from complex antigens. J. Immunol. 2001;166:6665–6670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwok WW, Gebe J, Liu A, Agar S, Ptacek N, Hammer J, Koelle D, Nepom GT. Rapid epitope identification from complex class II restricted T cell antigens. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:583–588. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Worm M, Lee HH, Kleine-Tebbe J, Hafner RP, Laidler P, Healey D, Buhot C, Verhoef A, Maillere B, Kay AB, Larche M. Development and preliminary clinical evaluation of a peptide immunotherapy vaccine for cat allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;127:89–97. 97. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danke NA, Koelle DM, Yee C, Beheray S, Kwok WW. Autoreactive T cells in healthy individuals. J. Immunol. 2004;172:5967–5972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danke NA, Yang J, Greenbaum C, Kwok WW. Comparative study of GAD65-specific CD4+ T cells in healthy and type 1 diabetic subjects. J. Autoimmun. 2005;25:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mallone R, Kochik SA, Reijonen H, Carson BD, Ziegler SF, Kwok WW, Nepom GT. Functional avidity directs T-cell fate in autoreactive CD4+ T-cells. Blood. 2005;106:2798–2805. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oling V, Marttila J, Honen J, Knip M, Simell O, Nepom G, Reijonen H. GAD65- and proinsulin-specific CD4+ T-cells detected by MHC Class II tetramers in peripheral blood of type 1 diabetes patients and at-risk subjects. J Autoimmun. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.09.018. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veldman C, Eming R, Wolff-Franke S, Sonderstrup G, Kwok WW, Hertl M. Detection of low avidity desmoglein 3-reactive T cells in pemphigus vulgaris using HLA-DR beta 1*0402 tetramers. Clin. Immunol. 2007;122:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, Danke N, Roti M, Huston L, Greenbaum C, Pihoker C, James E, Kwok WW. CD4+ T cells from type 1 diabetic and healthy subjects exhibit different thresholds of activation to a naturally processed proinsulin epitope. J. Autoimmun. 2008;31:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Long SA, Walker MR, Rieck M, James E, Kwok WW, Sanda S, Pihoker C, Greenbaum C, Nepom GT, Buckner JH. Functional islet-specific Treg can be generated from CD4+ Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:612–620. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durinovic-Bello I, Wu RP, Gersuk VH, Sanda S, Shilling HG, Nepom GT. Insulin gene VNTR genotype associates with frequency and phenotype of the autoimmune response to proinsulin. Genes Immun. 2010;11:188–193. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.James EA, Moustakas AK, Bui J, Papadopoulos GK, Bondinas G, Buckner JH, Kwok WW. HLA-DR1001 presents “altered-self” peptides derived from joint-associated proteins by accepting citrulline in three of its binding pockets. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2909–2918. doi: 10.1002/art.27594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mattapallil MJ, Silver PB, Mattapallil JJ, Horai R, Karabekian Z, McDowell JH, Chan CC, James EA, Kwok WW, Sen HN, Nussenblatt RB, David CS, Caspi RR. Uveitis-associated epitopes of retinal antigens are pathogenic in the humanized mouse model of uveitis and identify autoaggressive T cells. J. Immunol. 2011;187:1977–1985. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raddassi K, Kent SC, Yang J, Bourcier K, Bradshaw EM, Seyfert-Margolis V, Nepom GT, Kwok WW, Hafler DA. Increased Frequencies of Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein/MHC Class II-Binding CD4 Cells in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Immunol. 2011;187:1039–1046. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pugliese A, Zeller M, Fernandez A, Jr., Zalcberg LJ, Bartlett RJ, Ricordi C, Pietropaolo M, Eisenbarth GS, Bennett ST, Patel DD. The insulin gene is transcribed in the human thymus and transcription levels correlated with allelic variation at the INS VNTR-IDDM2 susceptibility locus for type 1 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:293–297. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chentoufi AA, Polychronakos C. Insulin expression levels in the thymus modulate insulin-specific autoreactive T-cell tolerance: the mechanism by which the IDDM2 locus may predispose to diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:1383–1390. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laughlin E, Burke G, Pugliese A, Falk B, Nepom G. Recurrence of autoreactive antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in autoimmune diabetes after pancreas transplantation. Clin. Immunol. 2008;128:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.03.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vendrame F, Pileggi A, Laughlin E, Allende G, Martin-Pagola A, Molano RD, Diamantopoulos S, Standifer N, Geubtner K, Falk BA, Ichii H, Takahashi H, Snowhite I, Chen Z, Mendez A, Chen L, Sageshima J, Ruiz P, Ciancio G, Ricordi C, Reijonen H, Nepom GT, Burke GW, III, Pugliese A. Recurrence of type 1 diabetes after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation, despite immunosuppression, is associated with autoantibodies and pathogenic autoreactive CD4 T-cells. Diabetes. 2010;59:947–957. doi: 10.2337/db09-0498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snir O, Rieck M, Gebe JA, Yue BB, Rawlings CA, Nepom G, Malmstrom V, Buckner JH. Identification and functional characterization of T cells reactive to citrullinated vimentin in HLA-DRB1*0401-positive humanized mice and rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2873–2883. doi: 10.1002/art.30445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raki M, Fallang LE, Brottveit M, Bergseng E, Quarsten H, Lundin KE, Sollid LM. Tetramer visualization of gut-homing gluten-specific T cells in the peripheral blood of celiac disease patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:2831–2836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608610104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crawford F, Stadinski B, Jin N, Michels A, Nakayama M, Pratt P, Marrack P, Eisenbarth G, Kappler JW. Specificity and detection of insulin-reactive CD4+ T cells in type 1 diabetes in the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:16729–16734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113954108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Landais E, Romagnoli PA, Corper AL, Shires J, Altman JD, Wilson IA, Garcia KC, Teyton L. New design of MHC class II tetramers to accommodate fundamental principles of antigen presentation. J. Immunol. 2009;183:7949–7957. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong R, Lau R, Chang J, Kuus-Reichel T, Brichard V, Bruck C, Weber J. Immune responses to a class II helper peptide epitope in patients with stage III/IV resected melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:5004–5013. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aloysius MM, Mc Kechnie AJ, Robins RA, Verma C, Eremin JM, Farzaneh F, Habib NA, Bhalla J, Hardwick NR, Satthaporn S, Sreenivasan T, El-Sheemy M, Eremin O. Generation in vivo of peptide-specific cytotoxic T cells and presence of regulatory T cells during vaccination with hTERT (class I and II) peptide-pulsed DCs. J. Transl. Med. 2009;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Slingluff CL, Jr., Petroni GR, Olson WC, Smolkin ME, Ross MI, Haas NB, Grosh WW, Boisvert ME, Kirkwood JM, Chianese-Bullock KA. Effect of granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor on circulating CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses to a multipeptide melanoma vaccine: outcome of a multicenter randomized trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:7036–7044. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ayyoub M, Dojcinovic D, Pignon P, Raimbaud I, Schmidt J, Luescher I, Valmori D. Monitoring of NY-ESO-1 specific CD4+ T cells using molecularly defined MHC class II/His-tag-peptide tetramers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:7437–7442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001322107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maus MV, Riley JL, Kwok WW, Nepom GT, June CH. HLA tetramer-based artificial antigen-presenting cells for stimulation of CD4+ T cells. Clin. Immunol. 2003;106:16–22. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(02)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cochran JR, Cameron TO, Stern LJ. The relationship of MHC-peptide binding and T cell activation probed using chemically defined MHC class II oligomers. Immunity. 2000;12:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vollers SS, Stern LJ. Class II major histocompatibility complex tetramer staining: progress, problems, and prospects. Immunology. 2008;123:305–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.James EA, van Haren SD, Ettinger RA, Fijnvandraat K, Liberman JA, Kwok WW, Voorberg J, Pratt KP. T-cell responses in two unrelated hemophilia A inhibitor subjects include an epitope at the factor VIII R593C missense site. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011;9:689–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fourneau JM, Cohen H, van Endert PM. A chaperone-assisted high yield system for the production of HLA-DR4 tetramers in insect cells. J. Immunol. Methods. 2004;285:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang J, Jaramillo A, Shi R, Kwok WW, Mohanakumar T. In vivo biotinylation of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II/peptide complex by coexpression of BirA enzyme for the generation of MHC class II/tetramers. Hum. Immunol. 2004;65:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cunliffe SL, Wyer JR, Sutton JK, Lucas M, Harcourt G, Klenerman P, McMichael AJ, Kelleher AD. Optimization of peptide linker length in production of MHC class II/peptide tetrameric complexes increases yield and stability, and allows identification of antigen-specific CD4+T cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:3366–3375. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200212)32:12<3366::AID-IMMU3366>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ge X, Gebe JA, Bollyky PL, James EA, Yang J, Stern LJ, Kwok WW. Peptide-MHC cellular microarray with innovative data analysis system for simultaneously detecting multiple CD4 T-cell responses. PLoS. ONE. 2010;5:e11355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Soen Y, Chen DS, Kraft DL, Davis MM, Brown PO. Detection and characterization of cellular immune responses using peptide-MHC microarrays. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E65. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mallone R, Kochik SA, Laughlin E, Gersuk V, Reijonen H, Kwok WW, Nepom GT. Differential recognition and activation thresholds in human autoreactive GAD-specific T-cells. Diabetes. 2004;53:971–977. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]