Abstract

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR and JAK/STAT3 signaling pathways are important for regulating apoptosis, and are frequently activated in cancers. In this study, we targeted STAT3 and mTOR in human hepatocellular carcinoma Bel-7402 cells and examined the subsequent alterations in cellular apoptosis. The expression of STAT3 was silenced with small interfering RNA (siRNA)-expressing plasmid. The activity of mTOR was inhibited using rapamycin. Following treatment, Annexin V/propidium iodide staining followed by flow cytometry and Hoechst33258 immunofluorescence staining was used to examine cellular apoptosis. JC-1 staining was used to monitor depolarization of mitochondrial membrane (ΔΨm). Furthermore, the expression of activated caspase 3 protein was analyzed by Western blotting. Compared to non-treated or control siRNA-transfected cells, significantly higher levels of apoptosis were detected in siSTAT3-transfected or rapamycin-treated cells (P < 0.05), which was further enhanced in cells targeted for both molecules (P < 0.05). The pro-apoptotic effects were accompanied with concomitant depolarization of mitochondrial membrane and up-regulation of activated caspase 3. Combined treatments using rapamycin and STAT3 gene silencing significantly increases apoptosis in Bel-7402 cells, displaying more dramatic effect than any single treatment. This study provides evidence for targeting multiple molecules in cancer therapy.

Keywords: mTOR, STAT3, RNAi, rapamycin, apoptosis, hepatocelluar carcinoma.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignancy worldwide and HCC-associated annual mortality ranks the third among all tumors1. Its incidence, however, is still on the rise, and is predicted to plateau between 2015 and 20202. Despite the advancement of different therapeutic approaches, such as surgical resection, liver transplantation, interventional therapy, and percutaneous ablation, improvements in patients' outcomes are still quite limited3. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapies that effectively target the pathological alterations underlying HCC.

In complex biological systems, cells communicate with their microenvrionment through intertwined regulatory signaling networks4. In response to exogenous signals, cells differentiate, proliferate, or undergo cell death/apoptosis in order to maintain constant numbers and support organ functions5. Biological homeostasis in cell growth is achieved and fine-tuned by activating, as well as inhibitory signaling pathways. The constitutive functioning of the former and/or the diminished performance/loss of the latter causes sustained signal transduction leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation, resistance to apoptosis and subsequently, malignant growth6. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that abnormalities in many signaling pathways are associated with the pathogenesis of HCC.

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a key molecule in the phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (PKB/Akt)/mTOR signaling pathway that, through the activation of various downstream targets, critically regulates cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, gene transcription, protein synthesis, and cellular apoptosis7. mTOR is activated by multiple stimuli including growth factors and nutrients, which act sequentially through receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), PI3K, and PKB/Akt signaling cascade. Previous studies indicate that mTOR is frequently (67%, 37/55) overexpressed in human HCCs, as detected by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)8, and consistently, the mTOR pathway is activated in 40-50% of HCC patients9.

The signal transducer and activator, STAT3 regulates the expression of target genes involved in cell-cycle progression and apoptosis, and promotes cellular transformation as well as abnormal cell proliferation10,11. The deregulation and constitutive activation of STAT3 are frequently observed in a large number of primary tumors and cancer-derived cells including hematologic malignancies, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and HCC 12.

Studies have shown that mTOR phosphorylates STAT3 at Ser727, which is required for the latter to maximally activate the transcription of target genes13. In light of the crosstalk between mTOR and STAT3, and their frequent activations in HCC, we wanted to explore the functional consequences of targeting these two molecules on cellular apoptosis. To accomplish this, pGC-siSTAT3 was transfected into Bel-7402 cells using Lipofectamine 2000, silencing the expression of STAT3 to inhibit the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway. meanwhile we inhibited the phosphorylation of mTOR using rapamycin to inhibit the PKB/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. We showed that targeting either molecule significantly promotes apoptosis in HCC cells Bel-7402, and a further enhancement of apoptosis was achieved when both molecules were targeted.

Material and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

Human HCC cells Bel-7402 were obtained from the Research Laboratory (Department of General Surgery, the First Hospital of Jilin University). The cells were propagated in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 units/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All cell lines were maintained in a cell culture incubator at 37°C in humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, with media changed every three to four days. Cells were collected by trypsinization at 70-80% confluence. β-actin (C4, sc-47778) antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA), mTOR, phosphorylated p-mTOR (Ser 2448), and cleaved caspase 3 (p17) antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). STAT3 (Ab-727) antibody was from KeyGEN (Nanjing, China). The Goat anti-Mouse IgG -HRP (EarthOx) and the Goat anti-Rabbit IgG-HRP (Pierce) as secondary antibodies.The mTOR-specific inhibitor, rapamycin was from Alexis (Alexis, San Diego, CA).

Plasmid construction

An oligonucleotide duplex targeting 2,144 to 2,162 of human STAT3 mRNA sequence (GenBank accession number NM_0003150) was synthesized by Shanghai Sangon (Shanghai, China) as follows: forward, 5'-AAGCAGCAGCTGAACAACATGTTCAAGAGACATGTTGTTCAGCTGCTGCTT-3', and reverse, 5'-AAGCAGCAGCTGAACAACATGTCTCTTGAACATGTTGTTCAGCTGCTGCTT-3'. This oligonucleotide contains a sense strand of 19 nucleotides followed by a short spacer (TTCAAGAGA), an antisense strand, and five Ts that act as a RNA polymerase III transcriptional stop signal. The duplex was cloned into the pGCsi.U6/neoRFP plasmid (the Laboratory of General Surgery Department, the First Hospital of Jilin University) to generate pGC-siSTAT3. The resulting plasmid was transformed into E. coli JM109 cells, purified using the plasmid miniprep purifcation system B (BioDev, Beijing, China), and then verified by sequencing. As a negative control, a control siRNA oligonucleotide duplex targeting no known human genes was used: forward, 5'-CCGGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTTCAAGAGAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAATTTTTG-3', and reverse, 5'-AATTCAAAAATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTCTCTTGAAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAA-3'.

Transfections and treatments of cells

pGC-siSTAT3 (0.8μg)and pGC-siCtrl plasmids (0.8μg) were separately transfected into Bel-7402 cells (2×105cells per well, 24-well plate) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen)(2.0μL) following the manufacturer's instructions for 4 hours, after which time the transfection medium was replaced with regular growth medium. Cells were treated as indicated at 24 h after transfection. The transfection efficiency was determined by observing the expression of RFP reporter using an Olympus IX inverted microscope with a fluorescence attachment.

For rapamycin treatment, cells were incubated with 109 nmol/L rapamycin for 48 h at 37°C in humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Flow cytometry (FCM) analysis for apoptosis determination

Annexin-V/propidium iodide (PI) double assay was performed using the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection kit (KeyGEN Biotech). Following treatment, cells were released from the culture dish with trypsin and washed twice with PBS. 1 × 106 cells were resuspended in 500-μL binding buffer and stained with 5-μL FITC-labeled Annexin-V according to the manufacturer's instructions. 5-μL propidium iodide (PI) was added and allowed to incubate with cells for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. After further washes with PBS, cells were subjected to FCM analysis using BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The data were analyzed using CellQuest data acquisition and analysis software (BD Biosciences).

Hoechest33258 staining

Cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. Following further PBS wash, cells were incubated in 100-μL Hoechst33258 solution for 10 minutes in the dark at 37°C. The solution was then removed and cells were washed twice with PBS and analyzed using an inverted fluorescence microscope.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) assay using fluorescence microscopy

To monitor the alterations in mitochondrial membrane potential, JC-1 dye (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide, Invitrogen) was applied to Bel-7402 cells (2 μL/mL medium) and incubated with cells for 20 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2. JC-1 forms aggregates in healthy mitochondria and emits red fluorescence (excitation/emission 485/580 nm). In apoptotic and necrotic cells, JC-1 does not aggregate and exists as monomeric form with green fluorescence (excitation/emission 485/530 nm) that indicates the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential/depolarization. After the incubation, the dye was aspirated from the plates, and the plates were washed three times with 1× JC-1 buffer and examined with a fluorescent microscope (Leica DMI 4000, Germany) using both red and green channels. The data are expressed as the percentage of red fluorescence counts of both red and green fluorescent counts.

Protein extractions and Western blotting

Cells were rinsed once with ice-cold PBS and lysed in ice-cold cell lysis buffer (Walterson, London, UK) containing complete protease inhibitors cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). The protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay kit (KeyGEN Biotech) using a c-globulin standard curve.

Proteins were separated on 7.5-12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide (SDS-PAGE) gels, and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk in TBS-T (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.25% Tween 20, pH 7.5) at room temperature for 2 h followed by appropriate primary antibody in TBS and 5% skim milk overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBS-T, the membrane was incubated with a secondary antibody in TBS-T buffer for 2 h at room temperature, followed by three washes with TBS-T. Protein bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence ECL substrate (Walterson, London, UK) and quantified using the VisionWorksLS software (UVP, LLC Upland, CA). All primary antibodies were used at 1:500 and secondary antibodies at 1:1000.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were independently repeated three times and the results are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses of the differences between groups were performed by using the SigmaStat statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The criterion for statistical significance was P < 0.05.

Results

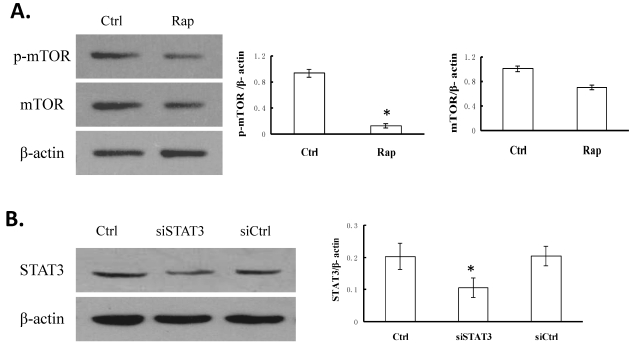

Rapamycin significantly inhibits the phosphorylation of mTOR in Bel-7402 cells

Following treatment with 109 nmol/L rapamycin (Rap) for 48 h at 37°C, the p-mTOR level was examined by Western blotting and compared with that in non-treated control (Ctrl) cells. As shown in Figure 1A, p-mTOR level was significantly reduced in Rap cells, as compared to in Ctrl cells (P < 0.05), while the level of total mTOR was not dramatically affected (P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Rapamycin inhibits the phosphorylation of mTOR and siSTAT3 specifically knocks down the level of STAT3 in Bel-7402 cells. A. Cells were treated without (Ctrl) or with 109 nmol/L rapamycin (Rap) for 48 h. The expression levels of phosphorylated mTOR (p-mTOR), total mTOR, and β-actin (as internal control) were examined by Western blotting. A representative image is shown on the left, and quantifications of p-mTOR/β-actin as well as mTOR/β-actin on the right. *P < 0.05, as compared to Ctrl cells. B. Cells were transfected with either pGC-siSTAT3 or pGC-siCtrl. The expression level of STAT3 was determined by Western blotting and compared to that in non-treated cells (Ctrl). A representative image is shown on the left, and quantification of STAT3/β-actin as well as mTOR/β-actin on the right. *P < 0.05, as compared to Ctrl cells.

STAT3 siRNA specifically knocks down STAT3 protein level in Bel-7402 cells

To reduce the expression of STAT3, we transfected Bel-7402 cells with pGC-siSTAT3 (siSTAT3). As a control, pGC-siCtrl plasmid was transfected (siCtrl). Compared to the non-transfected cells (Ctrl), siCtrl cells showed no reduction of STAT3 level, while siSTAT3 cells exhibited approximately 50% reduction in STAT3 level (P < 0.05, Figure 1B).

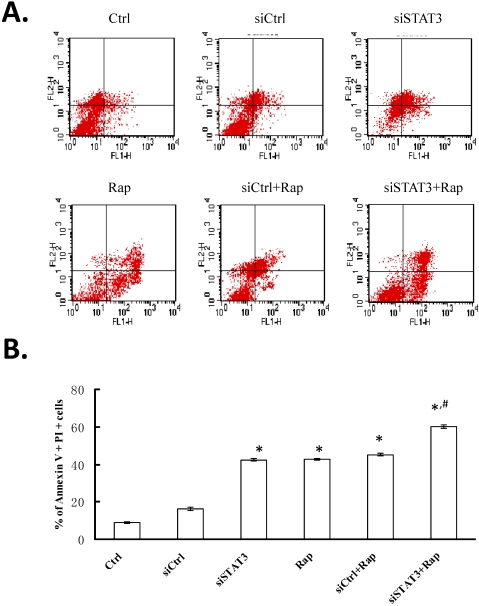

Targeting STAT3 and/or mTOR promotes cellular apoptosis in Bel-7402 cells

After Bel-7402 cells were transfected with either pGC-siSTAT3 or pGC-siCtrl and treated in the absence or presence of rapamycin, cellular apoptosis was first examined by Annexin V and PI staining followed by FCM analysis (Figure 2A). The percentage of apoptotic cells, as represented by dual PI and Annexin V positivity, ranged from 9.22±0.38% in non-treated Bel-7402 cells (Ctrl) to 16.47±1.04% in siCtrl, 42.73±0.88% in siSTAT3, 43.03±0.46% in rapamycin-treated (Rap), 45.44±0.59% in siCtrl+Rap, and 60.22±0.87% in siSTAT3+Rap cells (Figure 2B). Targeting either STAT3 with siRNA or mTOR with rapamycin significantly promoted apoptosis, as compared to non-treated or siCtrl-transfected cells (P < 0.05). This pro-apoptotic effect was further enhanced when both molecules were targeted (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Targeting STAT3 and/or mTOR promotes cellular apoptosis in Bel-7402 cells. Cells were treated as indicated at 24 h after transfection using Lipofectamine 2000 for 4 hours. For rapamycin treatment, cells were incubated with 109 nmol/L rapamycin for 48 h at 37°C in humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cells were stained with Annexin V (FL1 channel) and PI (FL2 channel), and analyzed by FCM. A. A representative FCM plot from each group is shown. Ctrl, non-treated control cells; siCtrl, cells transfected with control siRNA-expressing plasmid; siSTAT3, cells transfected with siSTAT3-expressing plasmid; Rap, cells treated with rapamycin; siCtrl+Rap, cells transfected with control siRNA-expressing plasmid and treated with rapamycin; siSTAT3+Rap: cells transfected with siSTAT3-expressing plasmid and treated with rapamycin. B. Percentage of dual Annexin V+PI+ cells from three independent experiments were quantified and presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, as compared to Ctrl and siCtrl groups; #P < 0.05, as compared to all other groups.

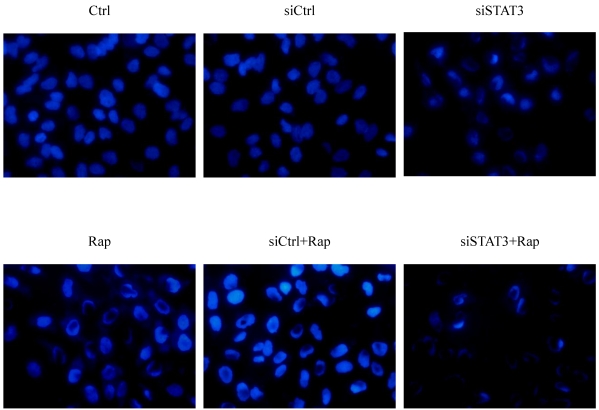

Consistent with FCM analysis, Bel-7402 cells also presented typical apoptotic morphology following treatment with siSTAT3, rapamycin, or both (Figure 3). These treatments not only reduced the number of cells remaining attached to the plate but also led to characteristic changes of chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation, with the most dramatic changes observed in cells treated with both siSTAT3 and rapamycin.

Figure 3.

Targeting STAT3 and/or mTOR promotes cellular apoptosis in Bel-7402 cells. Cells were treated as indicated, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. Following further PBS wash, cells were incubated in 100-μL Hoechst33258 solution for 10 minutes in the dark at 37°C, and imaged under inverted fluorescence microscope (× 400), with representative image from each group presented.

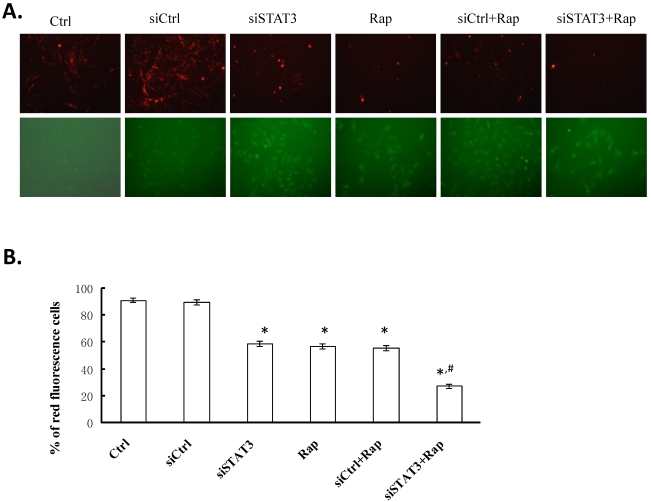

Targeting STAT3 and/or mTOR leads to mitochondrial depolarization in Bel-7402 cells

To examine whether targeting STAT3 and/or mTOR induces collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), we used JC-1, a cationic mitochondrial vital dye exhibiting potential-dependent accumulation in mitochondria, as represented by a shift of fluorescence emission from red in normal polarized mitochondria to green in abnormal depolarized mitochondria. As shown in Figure 4, targeting either STAT3 or mTOR significantly reduced the percentage of cells emitting red fluorescence (59.06±1.89% for siSTAT3 and 57.25±1.93% for Rap cells, respectively), as compared to non-treated control or siCtrl-transfected cells (91.33±1.78% for Ctrl and 89.90±1.92% for siCtrl cells, P < 0.05). Targeting both molecules resulted in the least number of cells with red fluorescence (27.28±1.82%, P < 0.05, as compared to all other groups), suggesting that disruption of mitochondria is, at least partially, responsible for the apoptotic effects induced by targeting both STAT3 and mTOR.

Figure 4.

Targeting STAT3 and/or mTOR leads to mitochondrial membrane depolarization in Bel-7402 cells. A. Cells were treated as indicated, stained with JC-1 dye, incubated with cells for 20 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and imaged under fluorescence microscope (× 200) at the emission wavelength of 580 nm (red, upper panels) and 530 nm (green, lower panels). A representative image from each group is shown. B. Percentage of red fluorescent cells from three independent experiments were quantified and presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, as compared to Ctrl and siCtrl groups; #P < 0.05, as compared to all other groups.

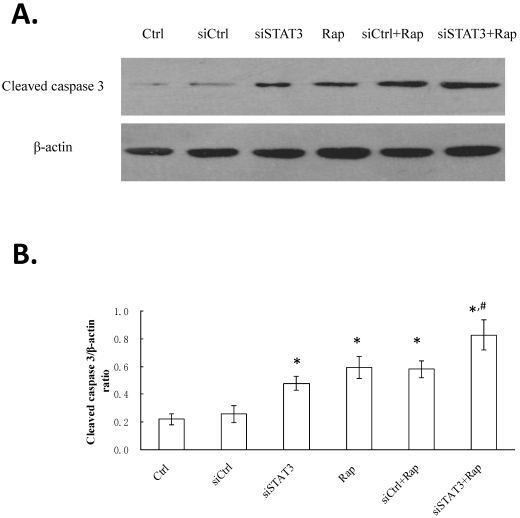

Targeting STAT3 and/or mTOR increases cleaved caspase 3 levels in Bel-7402 cells

Besides mitochondrial depolarization, the expression of cleaved/activated caspase 3 in Bel-7402 cells following different treatments was analyzed by Western blotting (Figure 5). The highest level was detected in cells targeted for both STAT3 and mTOR (siSTAT3+Rap), followed by those targeted for either molecule (siSTAT3, Rap, or siCtrl+Rap), and the lowest level was observed in non-treated control (Ctrl) or siCtrl-transfected (siCtrl) cells.

Figure 5.

Targeting STAT3 and/or mTOR increases cleaved caspase 3 levels in Bel-7402 cells. A. Cells were treated as indicated and Proteins were extracted. The expression of cleaved caspase 3 was determined by Western blotting, with representative gel image shown. β-actin expression was determined as internal control. B. Western signal intensity of cleaved caspase 3 was quantified using the VisionWorksLS software, standardized to the intensity of β-actin, and presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, as compared to Ctrl and siCtrl groups; #P < 0.05, as compared to all other groups.

Discussion

mTOR is a large molecular-weight (approximately 300 kDa) Ser/Thr protein kinase belonging to the family of phosphatidyl inositol kinase like proteins and mediates intracellular signaling related to cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation. Activated PI3K in response to several stimuli catalyzes the phosphorylation of phosphatidyl inositol 3, 4 diphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidyl inositol 3, 4, 5 triphosphate (PIP3), which binds to the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of PKB/Akt, recruiting and activating PKB/Akt. Phosphorylated PKB/Akt directly or indirectly phosphorylates mTOR and controls the level of p-Mtor14. Subsequently, p-mTOR regulates important cellular processes such as protein synthesis and cell proliferation through the activation of downstream targets including 4E-BP1 and S6K1. Consistent with its functions in regulating cell growth, mTOR is a crucial molecule in the generation and development of many tumors, rendering it an important target for tumor gene therapy15,16.

Rapamycin is a macrocyclic lactone antibiotic produced by Streptomyces hygrocopicus and was first discovered on Easter Island in a natural product screen for fungicides17. It binds to the FK506 binding protein (FKBP)/rapamycin-binding (FRB) domain in mTOR to block the phosphorylation of downstream effectors, including S6K1 and 4E-BP1, and thus inhibits the transition from G1 to S phase cell cycle 18. Previous studies suggested that rapamycin has anticancer activity in numerous tumor types19.

Many evidence showed that STAT3 plays a crucial role in oncogenesis. STAT3 acts downstream of cytokine receptors, growth factor receptors and cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases. Activation of STAT3 occurs by the JAK (Janus Kinase) that are associated with cytokine receptors, upon ligand binding with, e.g. growth factors, hormones and oncogenes 21. The phosphorylated STAT3 carries signals into the nucleus and binds to specific DNA response elements to regulate the transcription of many genes, such as Cyclin D, myc, Bcl-xl and Mcl-1 20. Consequently, STAT3 is significantly involved in the proliferation and anti-apoptosis of cancer cells.

In this study, we applied RNAi to specifically down-regulate the expression of STAT3. Here we obtained 50% inhibition of STAT3 expression by transfecting Bel -7402 cells with siRNA targeting specifically STAT3. STAT3 knockdown was incomplete. Since requirements for efficient shRNA biogenesis and target suppression are largely unknown, many predicted shRNAs fail to efficiently suppress their target22. As reported before, mTOR is involved in the serine phosphorylation of STAT3 23.Likewise, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors, rapamycin, abolished the phosphorylation effect of mTOR. The dephosphorylation of mTOR would more inhibited activation of STAT3.

Hepatocarcinogenesis is strongly linked to deregulation of major signaling pathways such as PI3K/Akt/mTOR and JAK/STAT324,25. In this study, we explored the potential of targeting these two signaling pathways and their effects on regulating cellular apoptosis. Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a complicated, genetically determined process involved in the development and maintenance of homeostasis in multicellular organisms. The capability of evading apoptosis is critical for the development and sustained growth of many, perhaps all, cancers, and the induction of apoptosis has now been considered as an important approach for cancer therapy26. In this study, we showed that targeting either STAT3 or mTOR significantly induced apoptosis in Bel-7402 cells; in addition, the combined treatment displayed further enhancement in apoptosis, as demonstrated by both FCM and Hoechst33258 staining.

It is known that apoptosis can be triggered in a cell through either the extrinsic/death receptor-mediated or intrinsic/mitochondria-mediated pathway. Thus, we further characterized the nature of apoptosis induced by targeting STAT3 and/or mTOR. We found that following treatment with either siSTAT3 or rapamycin, there was significant decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential, as indicated by the decrease in JC-1 dye aggregates (red) and increase in its monomers (green). The mitochondrial depolarization became even dramatic with combined treatments, suggesting that both STAT3 and mTOR are essential for maintaining mitochondrial integrity. The ΔΨm depolarization triggers the release of cytochrome c that activates caspases in the cytosol and subsequently initiates the apoptotic cascade. Consistently, Western blot showed that the expression of cleaved/activated caspase3 by treatment with both siSTAT3 and rapamycin is up-regulated, significantly higher than that in other groups.

Although the combined treatments with siSTAT3 and rapamycin increased apoptosis, depolarized the mitrochondrial membrane, and up-regulated cleaved caspase 3, to a greater extent than either treatment alone, we did not observe an additive effect. We made the conjecture that the cause involves two factors. On one hand, the improved pro-apoptotic activity of combined treatments suggests that these two signaling pathways do not converge on the exact same targets to regulate apoptosis. On the other hand, the short of additive effects implies that they do not work mutually exclusively in modulating apoptosis. This is consistent with a previous observation that mTOR directly phosphorylates STAT3, which is required for the optimal activity of the latter to regulate downstream targets.

In conclusion, the present work demonstrates that combined treatments using rapamycin and STAT3 gene silencing more potently promotes apoptosis in Bel-7402 cells, as compared to targeting either molecule alone. This study lays the groundwork for future development of multi-target drugs in cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the Laboratory of General Surgery Department (the First Hospital of Jilin University) and Hong-Dan Li (Liaoning Medical University) for their insights and technical support.

We thank Medjaden Bioscience Limited for assisting in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.EI-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinom: epidemiology and molecular cacinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM. Updated treatment approach to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:225–235. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1566-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando E, Tanaka M, Yamashita F. et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis: analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 2002;95:588–595. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beerenwinkel N, Antal T, Dingli D. et al. Genetic progression and the waiting time to cancer. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boland CR, Goel A. Somatic evolution of cancer cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:436–450. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bild AH, Potti A, Nevins JR. Linking oncogenic pathways with therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:735–741. doi: 10.1038/nrc1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dworakowska D, Wlodek E, Leontiou CA. et al. Activation of RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in pituitary adenomas and their effects on downstream effectors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:1329–1338. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hui IC, Tung EK, Sze KM. et al. Rapamycin and CCI-779 inhibit the mammalian target of rapamycin signalling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2010;30:65–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treiber G. mTOR inhibitors for hepatocellular cancer: a forward-moving target. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:247–261. doi: 10.1586/14737140.9.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng G, Lin J. Evaluation of potential Stat3-regulated genes in human breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seita J, Asakawa M, Ooehara J. et al. Interleukin-27 directly induces differentiation in hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2008;111:1903–1912. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li WC, Ye SL, Sun RX. et al. Inhibition of growth and metastasis of human hepatocellular carcinoma by antisense oligonucleotide targeting signal transducer and activator of transcription3. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7140–7148. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiyotaka Yokogami, Shinichiro Wakisaka, Joseph Avruch. et al. Serine phosphorylation and maximal activation of STAT3 during CNTF signaling is mediated by the rapamycin target mTOR. Current Biology. 2000;10:47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)00268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosner M, Hanneder M, Siegel N. et al. The mTOR pathway and its role in human genetic diseases. Mutat Res. 2008;659:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansure JJ, Nassim R, Chevalier S. et al. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin as a therapeutic strategy in the management of bladder cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:2339–2347. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.24.9987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato T, Nakashima A, Tamanoi F. Rheb-mTOR signaling pathway involved in tumor formation. Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso. 2010;55:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shailly Varma, Ramji L. Khandelwal. Effects of rapamycin on cell proliferation and phosphorylation of mTOR and p70S6K in HepG2 and HepG2 cells overexpressing constitutively active Akt/PKB. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1770:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudes GR. Targeting mTOR in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115:2313–2320. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petroulakis E, Mamane Y, Le Bacquer O. et al. mTOR signaling: implications for cancer and anticancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:R11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niu G, Bowman T, Huang M. et al. Roles of activated Src and Stat3 signaling in melanoma tumor cell growth. Oncogene. 2002;21:7001–7110. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al Zaid Siddiquee K, Turkson J. STAT3 as a target for inducing apoptosis in solid and hematological tumors. Cell Res. 2008;18:254–267. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fellmann C, Zuber J, McJunkin K. et al. Functional Identification of Optimized RNAi Triggers Using a Massively Parallel Sensor Assay. Molecular Cell. 2011;41:733–746. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.M. Okamoto, C. Lee, R. Oyas. Interleukin-6 as a paracrine and autocrine growth factor in human prostatic carcinoma cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 1997;57:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yam JW, Wong CM, Ng IO. Molecular and functional genetics of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2010;2:117–134. doi: 10.2741/s51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bromberg J, Wang TC. Inflammation and cancer: IL-6 and STAT3 complete the link. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:79–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farnebo M, Bykov VJ, Wiman KG. The p53 tumor suppressor: a master regulator of diverse cellular processes and therapeutic target in cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]