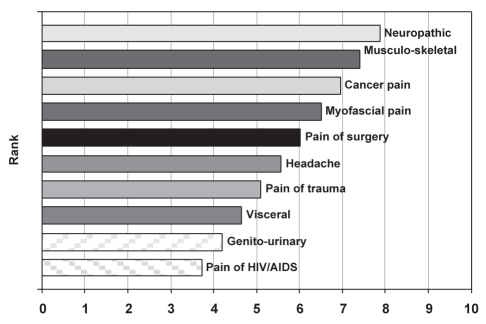

Despite the global problem of unrelieved pain, there are only limited data regarding its prevalence and incidence. Previous studies have reported estimates of chronic pain that range from as low as 5% to greater than 30% in developing countries, with an average of approximately 20% in developed countries. According to a survey conducted by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) in developing countries, neuropathic pain ranks first, followed by musculoskeletal and cancer pain. Poor education of health professionals, limited resources and access to drugs for pain relief has contributed to a ‘treatment gap’ in developing countries. This article provides a brief overview of programs and initiatives established by the IASP and its associated working groups to improve pain education and the clinical management of pain in developing countries. Also highlighted are more recent IASP-led campaigns to raise the profile of pain in health professionals, health providers and the general public.

Keywords: Developing countries, IASP, International Association for the Study of Pain, Pain education

Abstract

Unrelieved pain remains a global health problem. There is a major difference between what could be done to relieve pain and what is being done in developing countries – this is known as the ‘treatment gap’. Poor education of health professionals, limited facilities for pain treatment and poor access to drugs for pain relief are contributing factors. While enthusiasm for pain education and clinical training in developing countries has grown, restrictions by governments and health administrations have represented a significant barrier to practice changes. Since 2002, the International Association for the Study of Pain, through its Developing Countries Working Group, has established a series of programs that have resulted in significant improvements in pain education and the clinical management of pain, together with the beginnings of a system of pain centres. These pain centres will act as regional hubs for the future expansion of education and training in pain management in developing countries. Further success will be increased with the demolition of barriers to the treatment of people in pain worldwide.

Abstract

La douleur non soulagée demeure un problème de santé mondial. Il y a une différence majeure entre ce qui pourrait être fait pour soulager la douleur et ce qui est fait dans les pays en développement. C’est ce qu’on appelle une « disparité de traitement ». Le peu de formation des professionnels de la santé, les endroits limités pour traiter la douleur et le peu d’accès aux médicaments pour soulager la douleur contribuent à cette situation. L’enthousiasme envers l’enseignement et la formation clinique sur la douleur s’est accru dans les pays en développement, mais les restrictions imposées par les gouvernements et les administrations de la santé ont représenté un obstacle considérable aux changements de pratique. Depuis 2002, l’Association internationale pour l’étude de la douleur, par l’entremise de son groupe de travail dans les pays en développement, a mis sur pied une série de programmes qui ont suscité des améliorations significatives à l’enseignement sur la douleur et à la prise en charge clinique de la douleur, de même que l’amorce d’un système de centres de prise en charge de la douleur. Ces centres serviront de noyaux régionaux pour la future expansion de l’enseignement et de la formation sur la prise en charge de la douleur dans les pays en développement. On obtiendra encore plus de résultats lorsqu’on aura vaincu les obstacles au traitement des personnes souffrant de douleur dans le monde.

Unrelieved pain remains a global health problem; however, reliable data regarding the prevalence and incidence of pain are limited, particularly for developing countries. To illustrate the scale of the problem from existing data, information from a WHO collaborative study of pain in primary care (1) revealed that chronic pain was present in approximately 5% to 33% of individuals in developing countries. Data from economically advantaged countries revealed that, at any one time, between 18% and 20% of the population suffer from chronic pain. A detailed study by Breivik et al (2) in 15 European countries revealed a range of 15% to 30% of individuals with chronic pain, while a large-scale survey in Australia (3) reported a prevalence of 18.5% of adults with pain daily for three or more months. A similar figure of 19% was obtained in Denmark (4). The WHO study revealed that chronic pain was associated with depression, which affected the daily lives of individuals concerned (1), and a figure of 20% was quoted in the European study (2). In the case of developing countries, the WHO study also suggested that lack of an adequate social and health care support network, cost implications and job security must influence the extent to which those living in developing countries suffer pain but fail to seek help for it (1).

Chronic pain in the European study showed that 61% of sufferers were less able or unable to work outside the home, and that 19% had lost their jobs because of pain. In this study, the most common causes of pain were musculoskeletal (30% to 40%), neck and back (30%), headache and migraine (7%), and cancer (1% to 2%) (2). A survey of education and pain management in developing countries by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (5) revealed that IASP members in those countries listed the frequency of the pain they encountered in practice (Figure 1). Neuropathic pain was the most common type, followed by musculoskeletal and cancer pain. Rather surprisingly, pain arising from advanced AIDS was least often reported, although it was discovered that a greater part of AIDS-related pain is dealt with by oncologists and palliative care specialists. Other important causes of acute or chronic pain in developing countries are caused through childbirth, sickle cell disease, accidents and landmine injuries.

Figure 1).

Ranked frequency of pain types treated

PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH THE TREATMENT OF PAIN IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

There is a major difference between what could be done to relieve pain and what is actually being achieved in developing countries – this is known as the ‘treatment gap’. It exists in developing countries, primarily as a result of the poor education of health professionals, limited facilities for pain treatment and poor access to drugs for pain relief. In the case of opioids, there is often a high level of opioid phobia among health providers, doctors, nurses and patients. Table 1 summarizes the main obstacles to good pain management as reported by IASP developing country members. With respect to the availability of opioids for the treatment of severe pain, two examples reveal a significant difference between the economically advantaged and disadvantaged countries of the world. In Europe, as a whole, approximately 80% of opioids are consumed in Western countries and only 20% in the East, with the exception of pethidine, which is consumed in approximately equal proportions. In India, it has been revealed that, in 2009, the Government Opium Alkaloid Works produced less than 10% of the morphine needed in the country for cancer patients experiencing pain (6).

TABLE 1.

Barriers to good pain management: IASP survey of developing countries

| Barriers | Percentage of respondents reporting |

|---|---|

| Lack of education | 91 |

| Government policies | 74 |

| Fear of opioid addiction | 69 |

| High cost of drugs | 58 |

| Poor patient compliance | 35 |

| Other | 11 |

IASP International Association for the Study of Pain

IASP EDUCATION AND CLINICAL TRAINING INITIATIVES

Given the belief that pain treatment and facilities for treatment in developing countries were much scarcer there than in the west, in 2002, the IASP decided to increase its support for pain education and clinical training in pain management in developing countries to a substantial degree – a decision that was supported by the results of a survey that was conducted in 2007 (5). The initiatives that have been developed since 2002 fall into the following four groups: the first initiative developed was a program of pain education grants with 10 one-year projects per annum, each funded to a maximum of US$10,000; in the second initiative, the concept of clinical training centres has been pursued through a pilot development in Bangkok, Thailand; the third initiative involved granting financial aid to bodies external to the IASP involved in projects in developing countries, in which pain management is a significant part of their program; finally, the IASP implemented the Global Year Against Pain program.

Education

Since 2005, and via a Developing Countries Working Group, the IASP has distributed funds to support 57 one-year projects in 32 countries. The nature of the projects, which reflect local needs rather than a top-down view from the IASP, vary widely. For example, there have been workshops on pain education and management (China 2006); a train-the-trainer program for paramedical trainees and medical undergraduates (India 2007); instruction in opioid storage and use for patients with cancer or AIDS, as a program for pharmacists (Egypt 2008); a course on management of pain by nurses involved in palliative care (Peru 2008); and pain education courses at seven universities for physiotherapists, rehabilitationists and clinical workers (Nigeria 2009). The applications for grants were assessed using standard criteria (Table 2) and included a requirement for pre- and postcourse assessments of students. The great majority of projects satisfactorily achieved their goals.

TABLE 2.

IASP education program: Application assessment criteria

| 1 | Evidence of good organization, educational expertise, basic knowledge of pain mechanisms and clinical management |

| 2 | Local needs clearly identified as basis for application |

| 3 | Curriculum must match students and needs and be based on written materials or distance learning course |

| 4 | Clear plan for pre- and postcourse written, oral or practical assessments as appropriate |

| 5 | Detailed and realistic budget with minimum social costs |

Criterion rated 0–3; overall rating 1–4. IASP International Association for the Study of Pain

However, the outcome of two projects illustrates that they may reveal unexpected results following the completion of the course. For example, a procedural sedation and analgesia course (Guyana 2008) was followed by an overwhelming demand for repeated courses. In contrast, a basic pain education program in a South American country revealed that nurses recruited to the course did not regard their role in pain management to be considerable, believing it was the responsibility of the doctors. Other negative outcomes included reluctance to prescribe opioids and other analgesics, and ‘discomfort’ among students in a cancer pain/palliative care course. Perhaps it should have been anticipated that local fears, for example, opioid phobia or fear of the emotional problems of terminally ill patients, would be revealed by some of the projects. The fact that they surfaced added new dimensions for the projects’ designers who had not expected them. Other problems were that some universities sought to use part of the education grant for administrative purposes, governments placed restrictions on the use of opioids and there was a lack of interest in pain by health administrators in some countries.

The barriers to good pain management, which were identified in the IASP survey (Table 1), were mirrored to some extent in the various one-year projects.

Clinical training

In collaboration with the World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiology, the IASP supported an already established, multi-disciplinary pain clinic in Bangkok, specifically via one-year and three-month fellowships. This pilot scheme is in its third year. Apart from giving postgraduates, in short- and long-term training, a thorough, multidisciplinary education in pain management and clinical training, it has produced trainees who will return to develop pain services and education in their own countries. The one-year fellowships have been taken up by postgraduates from Malaysia, Laos and Mongolia, and three-month fellowships by doctors from Myanmar, Bhutan and Laos. The training periods are followed by mentorship from the centre in Bangkok. Moreover, help from that centre is given through the organization of local and national meetings that the IASP also supports.

A similar arrangement to that in Bangkok was started in Bogota, Colombia this year. The IASP intends to establish centres in other regions, for example, South Africa and India, with the intention of centres serving as a focus for the countries surrounding them, in which as a result, new clinical initiatives will develop. Several regional groups have emerged. The first was the Federation of IASP Chapters, with the European Federation of IASP Chapters at its centre. Other regional activities have appeared, for example, the Asian IASP chapters have formed an organization – the Association of Southeast Asian Pain Societies (ASEAPS) – which held its third meeting in Thailand in May 2011. That will be linked to an IASP ‘pain camp’ lasting five days, which will consist of an education program financially supported by the IASP and visiting lecturers. This is a new initiative; the purpose of the camp is to attract newcomers to the field of pain management from ASEAPS countries, thereby reinforcing the existing IASP centre concept.

The third IASP initiative involved giving grants to organizations working in developing countries with pain as a major part of their programs. Three groups have been or are being supported. WHO has received support for their work in Africa dealing with cancer, AIDS and palliative care. Kybele, an organization that aims to reduce maternal and infant mortality in developing countries, and Hospice Africa, which began in Uganda and now covers much of sub-Saharan Africa, are both currently in receipt of IASP grants. In all cases, IASP funds support either clinical pain management or the education of health professionals in the pain management aspect of their work.

Finally, based on the European Week Against Pain, established by the European Federation of IASP Chapters in 2001, the IASP has supported seven full IASP Global Year Against Pain campaigns to date, which are listed in Table 3. The Global Year concept is to encourage members of IASP, through their chapters, to raise the profile of pain in health professionals, health providers (including governments) and the general public. These campaigns are exercises in advocacy and also yield very useful fact sheets. The topics have been selected on the basis of groups within the general population because in the wide field of pain management, they are the least well cared for. Pain treatment, as a human right, is a major moral target that underlies all IASP activities directly related to pain sufferers.

TABLE 3.

IASP Global Year Against Pain initiatives since 2004

| 2004/2005 | Pain relief is a human right |

| 2005/2006 | Pain in children |

| 2006/2007 | Pain in older persons |

| 2007/2008 | Pain in women |

| 2008/2009 | Pain in cancer |

| 2009/2010 | Musculoskeletal pain |

| 2010/2011 | Acute pain |

IASP International Association for the Study of Pain

A recent review of IASP’s work in developing countries led to a refinement of its strategies. The main elements are shown in Table 4 and represent an expansion of the existing programs. It has become clear that since 2002, the effect of IASP initiatives has been to release great enthusiasm for pain education and clinical training in developing countries; however, restrictions implemented by governments and health administrations represent a significant barrier. The IASP wishes to break down these obstructions through programs directed at government-imposed restrictions, for example, in the use of opioids or the lack of pain relief as a priority, in favour of treatments for infection or by regarding pain as simply a symptom of disease. The concept of pain treatment as a human right, the use of pain as the fifth vital sign, and work to change regulations imposed on the use of opioids are all important and were brought together at a Pain Summit at the IASP 13th World Congress held in Montreal, Quebec, in August 2010.

TABLE 4.

Main strategic objectives: IASP DCWG 2010

| 1. | Support/develop regional centres of excellence. Train-the-trainers, local cultural and geographical needs for pain education |

| 2. | Collaborate with WHO and governments in developing countries to change health policies in favour of higher priority for pain management |

| 3. | Partner (twin) developed and developing country chapters |

| 4. | Continue pain education grants |

| 5. | Develop mentoring programs |

| 6. | Facilitate transition of IASP educational materials* |

Existing curricula to be updated by newly appointed task force. DCWG Developing Countries Working Group; IASP International Association for the Study of Pain

CONCLUSION

Since 2002, the IASP, through its Developing Countries Working Group, has established a series of programs that has resulted in significant improvements in pain education and the clinical management of pain, together with the beginnings of a system of pain centres that will act as regional hubs for the future expansion of education and training in pain management in developing countries. Further success will be increased with the demolition of barriers to the treatment of people in pain worldwide

REFERENCES

- 1.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: A World Health Organisation study in primary care. JAMA. 1998;280:147–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breivik H, Collett V, Ventafridda V. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain in Australia: A prevalence study. Pain. 2001;89:127–34. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eriksen J, Jensen MK, Sjogren P, Ekholm O, Rasmuseen MK. Epidemiology of chronic non-malignant pain in Denmark. Pain. 2003;106:221–8. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Association for the Study of Pain Survey of education and pain management in developing countries. < www-iasp.pain.org/> (Accessed on November 15, 2007).

- 6.Pallium India < http://palliumindia.org> (Accessed on June 23, 2009).