Addressing the global prevalence of chronic and unrelieved pain, especially in developing countries, requires heightened awareness (particularly to the socioeconomic burden of pain), enhanced pain education, improvements to pain care and increases to pain research resources. This article begins with a brief overview of recent advances in pain research and management, and subsequently identifies several opportunities and approaches to confront the global epidemic of chronic pain and its related issues, acknowledging that the variability among countries in health care policies, programs and resources will require specific tailoring to each country’s socioeconomic and educational situation.

Keywords: Access, Awareness, Education, Pain, Research

Abstract

Despite many recent advances in the past 40 years in the understanding of pain mechanisms, and in pain diagnosis and management, considerable gaps in knowledge remain, with chronic pain present in epidemic proportions in most countries. It is often unrelieved and is associated with significant socioeconomic burdens. Several opportunities and approaches to address this crisis are identified in the present article. Most crucial is the need to increase pain awareness, enhance pain education, improve access to pain care and increase pain research resources. Given the variability among countries in health care policies and programs, resources and educational programs, many of the approaches and strategies outlined will need to be tailored to each country’s socioeconomic and educational situation.

Abstract

Malgré de nombreux progrès dans la compréhension des mécanismes de la douleur et dans le diagnostic et la prise en charge de la douleur depuis 30 ans, il reste d’énormes lacunes sur le plan des connaissances, la douleur chronique étant présente en proportions épidémiques dans la plupart des pays. Souvent, elle n’est pas soulagée et s’associe à d’importants fardeaux socioéconomiques. Le présent article contient plusieurs possibilités et plusieurs démarches pour régler cette crise. Il est particulièrement nécessaire d’augmenter la sensibilisation à la douleur, d’accroître la formation sur la douleur, d’améliorer l’accès aux soins de la douleur et d’enrichir les ressources de recherche sur la douleur. Étant donné la variabilité des politiques et des programmes, des ressources et des programmes de formation en matière de santé selon les pays, bon nombre des démarches et des stratégies présentées devront être adaptées à la situation socioéconomique et éducationnelle de chaque pays.

The past four decades have seen some considerable advances in our understanding and management of pain; however, pain, especially chronic pain, remains a problem of epidemic proportions in most countries. This is not only because of the partial understanding of the underlying mechanisms and the difficulties in the management of most chronic pain conditions, but also because of the limited levels of the following: awareness, particularly related to the socioeconomic burden of pain; education (especially of health professionals); access to care; and research and funding. The present article provides a brief overview of these advances, but focuses on these four areas and outlines some possible approaches for each to address the current crisis of unrelieved pain. Education in all its facets lies at the heart of all four factors and in the approaches needed to address them.

RECENT ADVANCES IN PAIN RESEARCH AND MANAGEMENT

Recent advances in pain research and management can be summarized as follows:

Recognition of the multidimensionality of pain and importance of biopsychosocial factors in pain expression and behaviour.

Identification of peripheral and central nociceptive processes.

Discovery of several endogenous neurochemicals and intrinsic pathways in the brain and their influences on nociceptive transmission and behaviour.

Development of concepts and insights of the neuroplasticity of pain processing that can lead to chronic pain.

Rapid advances in the field of brain imaging and molecular biology, and their applicability to the pain field.

Improvements in surgical, pharmacological and behavioural management of pain. These improvements include more effective and varied drug-delivery systems, a broader range of analgesic and other drugs for pain patients, spinal cord and brain stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, physical/rehabilitative medicine, and cognitive behavioural therapy (although the evidence base is limited for some of these).

Despite these advances over the past few decades, several problems confront the pain field, especially in the case of chronic pain, as noted below.

THE IMPACT OF PAIN

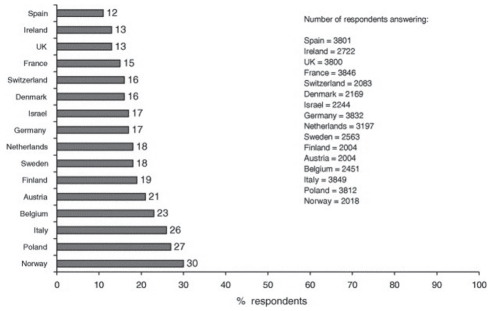

Pain is commonly divided into either acute or chronic pain. Acute pain is usually a warning signal of real or potential tissue damage, most evident as a result of accidental injury, inflammation and operative procedures. Fortunately, most acute pain conditions can be readily managed and will disappear after the traumatized tissue has healed. It is well documented, however, that approximately 20% of acute pain conditions can transition into chronic pain, which can be persistent or episodic, especially if the acute pain is not appropriately managed (1). Chronic pain may also be an accompaniment of many chronic diseases and disorders (eg, arthritis, diabetes, cancer, HIV/AIDS) or be ‘stand-alone’ (eg, fibromyalgia, migraine, temporomandibular disorders, trigeminal neuralgia). Chronic pain is usually regarded as having no biologically meaningful role, but it is very prevalent, with estimates in Europe, for example, ranging from 12% to 30% depending on the country surveyed (2) (Figure 1); in Canada, recent surveys (3,4) indicate that chronic pain occurs in approximately 20% of the adult population. Chronic pain, however, is a ‘silent epidemic’ because there is little awareness of its prevalence and social and economic costs, which are well documented (5–9). A recent Canadian survey (Nanos 2007/2008, www.painexplained.ca), for example, revealed that the personal costs to Canadians are enormous. These include the following:

Reduced quality of life (>50%)

Negative impact on relationships (29%)

Job loss or reduced job responsibilities (>50%)

Pain not effectively managed (55%)

Increased rates of depression (30%)

Twice the average likelihood of suicide while awaiting treatment.

Figure 1).

Prevalence of chronic pain in adults in 15 European countries. UK United Kingdom. Reproduced with permission from reference 2

Similar features apply to chronic pain in other countries (2,6,8).

In addition to these personal costs for the person suffering from unrelieved pain, there are the economic costs to the pain patient and to society as a whole. In Canada, the personal financial costs for pain patients is nearly $1,500 per month, while the costs to the Canadian economy are many billions of dollars per year, stemming from the costs of health care services, insurance, welfare benefits, lost productivity and lost tax revenues, etc (9,10). To put this value into perspective, in relation to health care costs of other disorders, unrelieved pain costs as much as cardiovascular disease or cancer, and twice as much as depression. In the United States (US), overall, pain costs are more than those of cancer and diabetes combined, and the annual health care costs plus lost productivity, compensation, etc, for pain are well over US$100 billion (8,9).

PAIN AWARENESS

Clearly, a crisis exists, and it is not going to get any better unless concerted efforts are made to improve awareness of pain and address its huge socioeconomic impact. As I (11) and others (9,12–14) have pointed out, it can be reasonably argued on the basis of demographic research that chronic pain conditions will become even more of a health problem and socioeconomic burden in most countries because changing demographics will result in an even higher proportion of the population being middle-aged and elderly. The latter represents the age cohorts in which most of the chronic pain conditions are especially prevalent and for which use of the health care system, and thereby costs of medications and other therapeutic approaches instituted to manage pain, are particularly high.

What needs to be done to increase awareness of this currently ‘silent’ and potentially expanding epidemic? Education in its broadest sense can provide important approaches. These include the following:

Inform public, government/policymakers, media, etc.

Synthesize new pain-related information for widespread readership by health care professionals.

Develop and widely distribute pain information sheets and articles for patients, health care professionals, government/policymakers, etc.

Collaborate with other stakeholders in these initiatives.

Inform and support mobilization of patient advocacy groups.

Several notable initiatives have been undertaken in recent years to raise general awareness about pain. These include the establishment, by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), of the first Global Day Against Pain and, subsequently, the Global Year Against Pain. These initiatives have been linked to and catalyzed national and regional awareness initiatives in IASP chapters around the world. Such initiatives in Canada include the National Pain Awareness Week, a collaborative effort of the Canadian Pain Society (the IASP chapter in Canada) and the patient-based Canadian Pain Coalition, assisted by the coordinating efforts of the ‘painexplained.ca’ awareness campaign.

Raising pain awareness needs to be part of a coordinated ‘pain strategy’ that includes integration with recent pain awareness campaigns, both nationally and internationally. It is to be hoped that the Pain Summit held in Montreal (Quebec), following the World Congress on Pain in September 2010, will provide strategic approaches that will have a global impact in raising pain awareness. An analogous national pain summit is being planned by the Canadian Pain Society to take place in 2012.

EDUCATION

Given the theme and interests of the symposium at which this article was originally presented, this section focuses particularly on pain education of health care professionals and students in health professional programs. There is considerable variability among clinicians in their education and knowledge of pain and the basis for their decision making (15). There is a continuing gap in the application of existing and recently acquired new insights into pain and its management, and several studies have pointed out the unacceptable levels of under-treatment that still exist for patients with cancer, HIV/AIDS, neonatal pain, following cardiac surgery, etc (16–21). Reasons for this range from the limited availability of effective analgesics in many countries, especially in most ‘developing’ countries as noted by Bond (22), beliefs about opioid use, government and legal limitations, and limited access to pain treatment (see below). It can also be argued that the lack of knowledge about pain and its complexity, coupled with many management approaches that have not been validated or fully tested for their sensitivity and specificity, result in some pain conditions being over-treated or inappropriately treated. Examples in my own professional discipline include the use of dental occlusal adjustments for temporomandibular disorders, and the well-documented frequent misdiagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia or atypical odontalgia by dental and medical clinicians (23–25).

Another factor that I have noted before (11) is the large variation around the world in implementing new knowledge and standards of practice and management for acute and chronic pain. The application of new knowledge by health professionals treating patients in pain can be particularly difficult – for example, in regions with economic and infrastructure limitations – as Bond has noted (22). While the information on the use of research data for appropriate modification of standards of practice in pain management is very limited, recent research initiatives in knowledge translation, as it applies to pain, hold promise of important breakthroughs in this area, as other symposium articles in the current of issue of the Journal have noted.

This limited knowledge and the misunderstanding of pain on the part of many health care professionals stem, in part, from the numerous other ‘competing’ diseases and disorders that most practising clinicians must be aware of and competent to manage, their relatively poor understanding of chronic pain mechanisms and the difficulty of treating most chronic pain conditions. A major contributing factor is the limited pain education that the vast majority of clinicians receive in their undergraduate and postgraduate professional programs. This is despite the following:

pain being an integral component of practice in medicine, dentistry, nursing, pharmacy and other health disciplines;

the high prevalence of pain conditions;

the huge socioeconomic costs of pain; and

the changing demographics that suggest future increases.

Therefore, it would appear logical – and even essential – that the two main targets of enhanced pain education should be health care professionals and students in health professional educational programs. For example, the topic of pain should be a significant part of the educational program for dental students, yet at most dental schools around the world, this topic comprises only a minor component of the dentistry curriculum (26). An analogous situation applies to most other health professional programs. This is clearly evident from a recent survey supported by the Canadian Pain Society of more than 40 health professions’ education programs across Canada (27) that addressed the extent of formal pain education during the entire educational program in dental, medical, nursing, occupational therapy, pharmacy and physical therapy; veterinary medicine programs were also surveyed for comparison (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Average total hours for designated mandatory formal pain content according to discipline*

| Faculty or department | Site responses, n | Total hours, mean ± SD | Range | Mean student, n* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dentistry | 5 | 15±10 | 0–24 | 47 |

| Medicine | 9 | 16±11 | 0–38 | 133 |

| Nursing | 9 | 31±42 | 0–109 | 133 |

| Occupational therapy | 3 | 28±25 | 0–48 | 47 |

| Pharmacy | 5 | 13±13 | 2–33 | 123 |

| Physical therapy | 7 | 41±16 | 18–69 | 55 |

| Veterinary medicine | 4 | 87±98 | 27–200 | 66 |

Outlier of 20 h at the University of Toronto (Toronto, Ontario) Centre for the Study of Pain interfaculty Pain Curriculum was excluded; only additional hour(s) for this site were included. Reproduced with permission from reference 27

It is remarkable that in Canada, on average, dental and medical students receive only 15 h to 16 h of formal education about pain throughout their multiyear program; some schools present no such formal education. Other health professional programs do somewhat better, but veterinary medicine is far ahead of the other professional programs, as Table 1 illustrates. An analogous situation occurs in other countries, such as the United Kingdom (28). Clearly, our pets and other animals are receiving health care from practitioners with much more knowledge about pain than their professional counterparts providing health care to humans.

This neglect of pain in the vast majority of health professional programs flies in the face of the current high prevalence of pain, its socioeconomic costs and the fact that pain is one of the major reasons for patients visiting physicians, dentists and other health care professionals. The relative neglect is also evident in the competency and accreditation requirements of graduating health care professionals. For example, in a recent survey I undertook of these competency requirements in Canadian and American dental schools (Association of Canadian Faculties of Dentistry; American Dental Education Association), I found that only two of 47 (Canada), and two of 39 (United States) requirements were related to pain and its diagnosis and management.

There are several steps that need to be taken to address this imbalance and improve clinicians’ understanding of pain. These include the following:

Increase pain curricular time for all students in all health professional programs.

Ensure pain is taught in an integrated manner reflecting its multidimensional nature and within a biopsychosocial framework.

Update and keep current pain curricula developed by national and international organizations (eg, IASP, International Headache Society).

Ensure sufficient coverage of pain exists in accreditation requirements and in practice standards for health care professionals, hospitals, etc.

Research and implement means ensuring effective knowledge transfer and application about pain and its management.

I recognize that local academic constraints and school ‘politics’ make it difficult to increase curricular content on pain in many universities, but it must be done if we are to improve the health care professionals’ knowledge of pain and its management for the betterment of the pain field and for the benefit of the pain patient. Indeed, increasing the curricular content on pain can be accomplished, as demonstrated by a recent initiative at the University of Toronto (Toronto, Ontario), where the shortcomings in the curricula for medical, dental, nursing, pharmacy and other health professional students were recognized.

Taking advantage of the recent pedagogic emphasis on interdisciplinary education, we have been successful, over the past decade, in setting aside a mandatory 20 h pain curriculum in the annual educational program of each health professional faculty. During this inter-faculty pain curriculum, the many facets of pain – from basic science to clinical management to patient issues – are presented in an integrated, interdisciplinary manner (29–31). Outcome measures indicate that this interdisciplinary and concentrated education initiative results in a much more ‘pain-savvy’ graduate.

ACCESS TO CARE

The crisis resulting from the limited awareness of pain, its complexity, its prevalence and socioeconomic costs, plus the limited education that most health care professionals receive about pain, is further compounded by the difficulty that many patients with pain, especially chronic pain, experience in gaining timely access to appropriate pain care. Yet, such access is a basic human right, recognized by the WHO, the United Nations and the IASP (32,33); this was reiterated at the recent international Pain Summit in Montreal. Furthermore, rapid access is essential because it has been well documented that chronic pain patients experience considerable deterioration in health-related quality of life and psychological well-being while waiting for treatment; the longer they have to wait for relief of their pain, the more severe the impact and the degree of chronicity and the greater the cost to the health care system (1). Surveys in several countries, including one recently conducted by the Canadian Pain Society, have revealed many inadequacies; in Canada for example (34,35), they include the following:

Access to timely and appropriate care for pain is unacceptably long.

Relatively few pain clinics, especially those providing multidisciplinary care.

Limited geographic distribution of pain clinics (>80% are in urban areas).

Few health care professionals with sufficient knowledge or training about pain.

Limited treatment options for many chronic pain conditions.

Limited cost coverage and availability of some management approaches, for example, through third party, provincial drug schedules, etc.

Access is especially problematic in most developing countries. For example, access to opioid drugs is very limited because of factors such as costs, opiate phobia, government restrictions and an inability to access prescribing clinicians, as noted by Bond (22).

Again, as with raising awareness and enhancing pain education (see above), local initiatives as well as coordination on a global perspective (eg, by IASP) are needed. For example, a recent IASP Task Force, co-chaired by Mary Lynch and myself, found that guidelines for appropriate wait times for access to treatment for chronic pain conditions were nonexistent in almost all countries; the task force provided recommendations to IASP for guidelines to be applied worldwide. The IASP is considering the task force’s report, and the process and means of pursuing multinational initiatives to address the timely and appropriate management of chronic pain on a global basis. It will be a challenge to have appropriate wait-times guidelines adopted around the world during this period of global fiscal restraint and burgeoning health care budgets. Nevertheless, each nation surely has an obligation to embrace the principle that all peoples have the right to timely access to appropriate care for chronic pain and to take steps to ensure that the principle is applied to all its citizens – it is a fundamental human right.

Some possible approaches to augment access include the following:

Ensure sufficient number of accessible pain clinics that offer timely and appropriate multidisciplinary care.

Establish more educational programs to provide a sufficient number of pain specialists.

Arrange accreditation of these programs and pain management clinics, with pain management/medicine a recognized specialty.

Advocate (to government/policymakers, insurance companies, etc) to ensure evidence-based management approaches are widely available.

Link with/build on analogous approaches in other countries.

Some steps have been taken along these lines. In addition to the pain summits and task forces noted above, accreditation of hospitals and other health care organizations that has taken into account means for access to appropriate pain management as well as the quality of that care has been an important step in some countries, such as the US, for pain to be regarded as a health system priority (36). In Canada, steps have been taken in some provinces to improve access at the community level, as noted in other presentations at this symposium.

RESEARCH AND FUNDING

Despite the remarkable advances in our understanding of pain and improvements in pain management approaches over the past 40 years, many challenges remain, the most notable being clarification of the mechanisms, etiology and pathogenesis of the many chronic pain conditions. Research initiatives need to be directed to the mechanisms accounting for differences between individuals in the pain experience, more meaningful (ie, clinically applicable) animal models of pain and translational approaches, and further exploration of the basic science and clinical utility of recent technologies related to brain imaging, biomarkers, genotyping, etc. Another increasingly important area of research is the processes and factors involved in the transition from acute to chronic pain; this need has been recognized by the National Institutes of Health in the US in its recent call for applications in this area.

Several factors hamper progress in advancing pain research. For example, although Canada is a world leader in many pain-related basic science and clinical fields, there is a relatively low proportion of pain researchers in this country compared with other health science fields. In addition, funding for pain research in Canada is also disproportionately low. Another recent survey supported by the Canadian Pain Society (37) found that the total amount of funding of pain research in Canada amounted to approximately $80 million over the past five years, which represents <1% of the total funding of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for health research. This contrasts markedly with cancer research, for example, which is supported by more than $300 million per year in Canada. Analogous proportions apply to other countries; in the US, for example, pain research accounts for <1% of all grants awarded by the National Institutes of Health (38).

Thus, the investment in pain research is hugely out of proportion to the prevalence and socioeconomic impact of pain, compared with other less common conditions (eg, cancer, heart disease, epilepsy, arthritis, HIV/AIDS, etc). Possible approaches to address these disparities include the following:

- Raise awareness of these disparities by educating policymakers and funding agencies of the need to place much increased emphasis on pain research by way of:

- ○ increases in human resources – that is, increased opportunities for training basic science and clinical pain researchers

- ○ increases in pain research funding and focus

- Ensure pain researchers are aware that the pain field can be more rapidly advanced by:

- ○ clarifying mechanisms involved in transition to chronic pain;

- ○ using recently developed and emerging technologies (eg, in brain imaging, molecular biology, genetics);

- ○ increasing emphasis on inter/multidisciplinary and translational research;

- ○ applying new basic science knowledge and evidence-based principles in clinical pain research; and

- ○ developing clinical databases and increasing emphasis on epidemiological studies and randomized clinical trials.

SUMMARY

There have been some remarkable advances in the past four decades in our understanding of pain mechanisms and in pain diagnosis and management.

Considerable gaps in knowledge and issues still exist, and chronic pain is present in epidemic proportions in most countries. It is often unrelieved and carries with it huge socioeconomic burdens.

- Several opportunities and approaches to enhance pain understanding and management have been identified. Most crucial is the need to:

- Enhance pain awareness and education, for example, by increasing pain curricular time and ensuring knowledge transfer and application; by more effective interactions between pain clinicians/researchersandthepublic,government/policymakers, media, and patient advocacy groups, etc.

- Improve access to pain care, for example, by ensuring a sufficient number of accessible pain clinics providing timely and appropriate multidisciplinary care.

- Increase pain research resources, for example, by increasing human resources and funding levels; by increasing emphasis on animal models and clinical studies, using inter-/multidisciplinary and translational approaches, including those that use newly developed and emerging technologies.

Given the variability between countries in health care policies and programs, resources and educational programs, many of the approaches and strategies outlined will need to be tailored to each country’s socioeconomic and educational situation.

Acknowledgments

The author’s own research studies are supported by NIH grant DE04786 and CIHR grants MT4918 and MOP82831. The author is the holder of a Canada Research Chair.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lynch ME, Campbell F, Clark AJ, et al. A systematic review of the effect of waiting for treatment for chronic pain. Pain. 2008;97:116. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brevik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulanger A, Clark A, Squire P, Cui E, Horbay GL. Chronic pain in Canada: Have we improved our management of chronic noncancer pain? Pain Res Manag. 2007;12:39–47. doi: 10.1155/2007/762180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moulin D, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Morley-Forster PK. Chronic pain in Canada – prevalence, treatment, impact and the role of opioids analgesia. Pain Res Manage. 2002;7:170–3. doi: 10.1155/2002/323085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee P. The economic impact of musculoskeletal disorders. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:S85–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00433381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA. 2003;290:2443–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henry JL. The need for knowledge translation in chronic pain. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13:465–76. doi: 10.1155/2008/321510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koestler AJ, Myers A. Understanding Chronic Pain. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philips CJ, Schopflocher D. The economics of pain. In: Taenzer P, Rashiq S, Schopflocher D, editors. Health Policy Perspectives on Chronic Pain. Weinheim: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerriere DN, Choinière M, Dion D, et al. The Canadian STOP-PAIN project, part 2: What is the cost of pain for patients on waitlists of multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities? Can J Anaesth. 2010;57:549–58. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sessle BJ. Outgoing president’s address: Issues and initiatives in pain education, communication, and research. In: Dostrovsky JO, Carr DB, Koltzenburg M, editors. Proceedings of the 10th World Congress on Pain, Progress in Pain Research and Management; Seattle: IASP Press; 2003. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green CR. The healthcare bubble through the lens of pain research, practice, and policy: Advice for the new President and Congress. J Pain. 2008;9:1071–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrell MJ. Pain and aging. Am Pain Soc Bull. 2000;10:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helme R, Gibson S. Pain in older people. In: Crombie IK, editor. Epidemiology of Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 1999. pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green CR, Wheeler JR, LaPorte F. Clinical decision making in pain management: Contributions of physician and patient characteristics to variations in practice. J Pain. 2003;4:29. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breitbart W. Pain in AIDS. In: Jensen TS, Turner JA, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, editors. Proceedings of the 8th World Congress on Pain Progress in Pain Research and Management; Seattle: IASP Press; 1997. pp. 63–100. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demyttenaere S, Finley GA, Johnston CC, McGrath PJ. Pain treatment thresholds in children after major surgery. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:173–7. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200106000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watt-Watson J, Stevens B, Katz J, Costello J, Reid D, David T. Impact of a pain education intervention on postoperative pain management. Pain. 2004;9:73–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stalnikowicz R, Mahamid R, Kaspi S, Brezis M. Undertreatment of acute pain in the emergency department: a challenge. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:173–6. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilson AM, Joranson DE, Maurer MA. Improving state pain policies: Recent progress and continuing opportunities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:341–53. doi: 10.3322/CA.57.6.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furlan AD, Reardon R, Weppler C. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: A new Canadian practice guideline. CMAJ. 2010;182:923–30. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bond M. Pain education issues in developing countries and responses to them by the International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain Res Manag. 2011;16:404–6. doi: 10.1155/2011/654746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sessle BJ, Baad-Hensen L, Svensson P. Orofacial pain. In: Lynch M, Craig K, Peng P, editors. Clinical Pain Management: A Practical Guide. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 258–66. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Truelove E. Management of mucosal pain. In: Sessle BJ, Lavigne GJ, Lund JP, Dubner R, editors. Orofacial Pain: From Basic Science to Clinical Management. 2nd edn. Chicago: Quintessence; 2008. pp. 187–93. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vickers ER, Cousins MJ, Walker S, Chisholm K. Analysis of 50 patients with atypical odontalgia. A preliminary report on pharmacological procedures for diagnosis and treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:24–32. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Attenasio R. The study of temporomandibular disorders and orofacial pain from the perspective of the predoctoral dental curriculum. J Orofac Pain. 2002;16:176–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, Hunter J, et al. A survey of prelicensure pain curricula in health science faculties in Canadian universities. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14:439–44. doi: 10.1155/2009/307932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briggs E, Carr ECJ, Whittaker M. Survey of undergraduate pain curricula for healthcare professionals in the United Kingdom. Eur J Pain. 2011;15:789–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter J, Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, et al. An interfaculty pain curriculum: Lessons learned from six years experience. Pain. 2008;140:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watt-Watson J, Hunter J, Pennefather P, et al. An integrated undergraduate pain curriculum, based on IASP curricula, for six health science faculties. Pain. 2004;110:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watt-Watson J. Moving the pain education agenda forward: Innovative models. Pain Res Manage. 2011;16:401. doi: 10.1155/2011/219621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bond M, Breivik H. Why pain control matters in a world full of killer diseases. Pain Clin Updates. 2004;12:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brennan F, Cousins MJ. Pain relief as a human right. Pain Clin Updates. 2004;12:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lynch ME, Campbell FA, Clark AJ, et al. Waiting for treatment for chronic pain – a survey of existing benchmarks: Toward establishing evidence-based benchmarks for medially acceptable waiting times. Pain Res Manage. 2007;12:245–8. doi: 10.1155/2007/891951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng P, Choiniere M, Dion D, et al. Challenges in accessing multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities in Canada. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54:977–84. doi: 10.1007/BF03016631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips DM. JCAHO pain management standards are unveiled. JAMA. 2000;284:428–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.423b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lynch ME, Schopflocher D, Taenzer P, Sinclair C. Research funding for pain in Canada. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14:113–5. doi: 10.1155/2009/746828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradshaw DH, Empy C, Davis P, Lipschitz D, Nakamura Y, Chapman CR. Trends in funding for research on pain: A report on the National Institutes of Health Grant Awards over the years 2003 to 2007. J Pain. 2008;9:1077–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]