Abstract

Objective

CD36 phosphorylation on its extracellular domain inhibits binding of thrombospondin-1. Mechanisms of cellular CD36 ectodomain phosphorylation and whether it can be regulated in cells are not known. We determined structure-function relationships of CD36 phosphorylation related to thrombospondin-1 peptide binding in vitro and explored mechanisms regulating phosphorylation by protein kinase C (PKC) in melanoma cells.

Methods and Results

Phosphorylation of CD36 peptide on Thr92 by PKCα suppressed binding of thrombospondin-1 peptides in vitro and the level of inhibition correlated with level of phosphorylation. Basal phosphorylation levels of CD36 in vivo in platelets, endothelial cells, and melanoma cells were assessed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblot and found to be very low. Treatment of CD36-transfected melanoma cells with phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA), a PKC activator, induced substantial CD36 phosphorylation and decreased ligand-mediated recruitment of Src-family proteins to CD36. PMA treatment did not induce detectable extracellular or cell surface-associated kinase activity and both cycloheximide and Brefeldin A blocked CD36 phosphorylation.

Conclusions

New protein synthesis and trafficking through the Golgi are required for PMA-induced CD36 phosphorylation, suggesting that phosphorylation probably occurs intracellularly. These studies suggest a novel in vivo pathway for CD36 phosphorylation that modulates cellular affinity for thrombospondin-related proteins to blunt vascular cell signaling.

Keywords: CD36, phosphorylation, Protein Kinase C (PKC), thrombospondin-1, angiogenesis

CD36 is a multi-ligand scavenger receptor expressed on the surface of platelets, microvascular endothelial cells (MVEC), mononuclear phagocytes, adipocytes, hepatocytes, myocytes and some epithelia 1. It was first identified as glycoprotein IV on platelets 2. On microvascular endothelial cells CD36 is a receptor for thrombospondin-1 and related proteins, and functions as a negative regulator of angiogenesis 1, 3-5 and therefore plays a role in tumor growth, inflammation, wound healing, and other pathological processes requiring neo-vascularizaton. Binding of thrombospondin-1 to CD36 inhibits growth factor-induced pro-angiogenic signals that mediate endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation and instead generates anti-angiogenic signals that lead to apoptosis 4, 6.

CD36 has been reported to be phosphorylated on a canonical protein kinase C (PKC) target sequence in human platelets, microvascular endothelial cells and CD36 transfected fibroblasts 7-8, although the relative proportion of CD36 that is phosphorylated under basal conditions has not been defined. Unusually, the site of CD36 phosphorylation (Thr92) is on its extracellular domain 7 where it has been shown to influence extracellular ligand binding. For example, phosphorylated CD36 does not bind thrombospondin-1 and has significantly lower affinity for Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes 7-8. It has been hypothesized that constitutive phosphorylation of platelet CD36 explains the lack of demonstrable binding of thrombospondin-1 to resting platelets despite abundant levels of surface CD36 expression, and that regulation of endothelial cell CD36 phosphorylation could influence angiogenesis and malaria cytoadhesion. Importantly, intracellular or extracellular mechanisms by which CD36 can be phosphorylated on its ecto-domain have not been identified, nor have molecular pathways by which phosphorylation can be regulated. Two groups have postulated that an extracellular protein kinase phosphorylates CD36 outside the cells 9-10, but convincing evidence for such an enzyme in vivo is lacking. Asch et al 7 have suggested that the key regulatory step in platelet CD36-thrombospondin binding is extracellular de-phosphorylation by an unknown ecto-phosphatase secreted from or activated by activated platelets.

The Thr92 extracellular phosphorylation site of CD36 is immediately adjacent to the CLESH (CD36, LIMP-2, EMP structural homology) domain. This domain, which spans from a.a. 93-120 was identified by us and others as the binding site for thrombospondin-1 and other anti-angiogenic proteins containing thrombospondin type 1 homology (TSR) domains 11-12. Although the mechanism by which Thr92 phosphorylation inhibits TSR-containing protein binding is not clear, it is reasonable to hypothesis that addition of a bulky phosphate group immediately upstream to the CLESH domain could disrupt the structure of the domain and/or block access to TSR containing proteins by steric hindrance. In the present studies we used recombinant peptides to show that TSR domains bind to the CLESH domain and that phosphorylation of a small recombinant protein containing the consensus PKC target site and the CLESH domain blocks TSR binding.

The observations that TSR-proteins have robust CD36-dependent anti-angiogenic activities in vitro and in vivo suggest that if indeed MVEC CD36 is phosphorylated under basal conditions, the level of phosphorylation must not be sufficient to prevent TSR-mediated responses. We thus propose that CD36 is only partially phosphorylated on MVEC and that up-regulation of phosphorylation might be a mechanism by which MVEC lose responsiveness to an important endogenous anti-angiogenic pathway triggered by TSR-proteins. In the present study, we showed that CD36 phosphorylation could be detected at low levels in cultured cells and that it can be further phosphorylated in vitro by exposure to active PKC. Furthermore, endogenous CD36 phosphorylation could be increased by exposing cells to the PKCα activator, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA). Induction of phosphorylation required new protein synthesis and trafficking through the Golgi, suggesting that only newly synthesized CD36 becomes phosphorylated and that phosphorylation occurs intracellularly. Finally, we showed that PMA induced phosphorylation inhibits CD36-mediated signaling downstream of TSR-proteins.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Antibodies to phospho-PKCα and phospho-threonine were purchased from Cell Signaling. Rabbit anti-CD36 polyclonal antibody (ab36977) and monoclonal IgG FA6-152 were purchased from Abcam. Polyclonal rabbit anti-PKCα antibody was from GIBCO. Human platelet TSP-1 was prepared as previously described 13 or purchased from CalBiochem. HRP-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from GE Healthcare. Enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (ECL) was purchased from Thermal Scientific. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) was purchased from Sigma.

Cells

Human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) were purchased from Lonza and maintained in microvascular endothelial cell growth medium (EGM-2 MV, Lonza) with full supplements (5%FBS, 0.4%hFGF-2, 0.1% VEGF, 0.1% R3-IGF-1, 0.1% hEGF, 0.04% hydrocortisone, 0.1% ascorbic acid, 0.1% GA-1000). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were provided by Dr. P. DiCorleto and maintained in endothelial cell growth medium (EGM-2, Lonza) with full supplements (EGM-2 bullet kit: 2%FBS, 0.4%hFGF-2, 0.1% VEGF, 0.1% R3-IGF-1, 0.1% hEGF, 0.04% hydrocortisone, 0.1% ascorbic acid, 0.1% heparin, 0.1% GA-1000). Bowes melanoma cells stably transfected with human CD36 cDNA or control plasmid were prepared and maintained as described previously 3. Human monocyte cell line, THP-1, was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10%FBS. Prior to PMA treatment, cells were placed in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 1% fetal bovine serum for 16h. In some studies cells were exposed to 100μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma) or 5ng/ml Brefeldin A (Biolegend) prior to assessing CD36 phosphorylation.

Recombinant proteins

A cDNA encoding an “extended” CD36 CLESH domain including the putative PKC target site around Thr92 was cloned by PCR from human endothelial cell cDNA with the following primer pairs: 5′-CACCAGCAACATTCAAGTTAAGCA-3′ and 5′-TCAGGCACCATTGGGCTGCAGGA-3′. PCR was performed with high fidelity DNA polymerase (Roche) and the products were gel-purified and cloned into the prokaryotic expression pET102 vectors (Invitrogen) by TA cloning to generate His-patched thioredoxin tagged fusion proteins. The plasmids were then transformed into BL21 competent cells (Invitrogen) and recombinant protein expression induced by 0.2mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 4h at 37°C. Recombinant proteins were purified after cell sonication by incubation with Ni++ beads and elution with immidazole. Dialyzed proteins were stored at -80°C. A T92A point - mutated CLESH domain was generated by overlap extension PCR with the following primer pairs: 5′-GGTCCTTATGCGTACAGAGTTCG-3′ and 5′-CGAACTCTGTACGCATAAGGACC-3′. The product was cloned and protein purified as described above. A plasmid encoding the second and third thrombospondin-1 TSR domains was obtained from Dr. J. Lawler (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) 14. The insert was re-cloned into the vector described above for purification of recombinant protein.

All constructs were sequenced by the dideoxynucleotide method to confirm that the recombinant protein sequences were correct and in frame. The recombinant proteins were also examined by western blotting and ELISA to confirm appropriate size and immuno-reactivity.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Cells were scraped and lysed in 500μl lysis buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 1% Triton, 2.5mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1mM beta-glycerophosphate, 1mM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitors tablet (1 tablet in 10ml lysis buffer, Roche) on ice for 5min. Lysates were then centrifuged at 12,000g for 5min to remove cell debris and supernatants containing 500μg of protein were incubated with monoclonal anti-CD36 IgG (1μg) or polyclonal anti-PKCα antibody at 4°C for 4h and then precipitated with 20μl protein G agarose beads (GE Healthcare) for another 4h. Isotype matched mouse IgG or non-immune rabbit Ig were used as controls. The beads were washed twice with lysis buffer at 4°C, resuspended in heated Laemmli sample buffer and boiled for 5min before being subjected to electrophoresis in 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). For detection, membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in 25mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20 for 1h at 22°C and then incubated with 1:1000 diluted primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Membranes were incubated with 1:5000 diluted HRP-linked secondary antibodies for 1h at 22°C and then washed and developed with ECL. The blot was quantified by scanning and analyzed by ImageJ software (NIH).

In vitro PKCα phosphorylation

Purified CD36 recombinant proteins (25μg) were diluted in 100μl kinase buffer (25mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5mM β-glycerophosphate, 2mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM MgCl2). 0.2mM ATP and 1ng/μl active PKCα (Cell Signaling) were added and incubated overnight at 37°C. In other experiments CD36 immunoprecipitates prepared as above were resuspended in 150μl kinase buffer and divided into three aliquots. PKCα (1ng/μl) was added to two aliquots and incubated at 37°C for 1h. At the end of the incubation, beads were washed twice and resuspended in 50μl phosphatase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol). In one tube, 10u purified alkaline phosphatase (New England Biolab) was added and incubated at 37°C for 1h. At the end of the incubation, beads were washed twice and processed for western blotting.

Solid phase protein binding assay

TSP-1 or recombinant TSR proteins (1μg) were immobilized on 96 well polystyrene plates by overnight incubation in 0.5M NaHCO3, pH 9.6 at 4°C. Saturation coating conditions were first determined using antibodies against coated proteins. The wells were then washed three times with TBST (20mM Tris-HCl, 150mM NaCl, pH 7.4, containing 0.1% Tween 20) and then blocked with 0.5% BSA in TBST at 22°C for 1h. Recombinant CD36 peptides were then added in TBST containing 1mM CaCl2 and incubated at 22°C for 2h. Wells were then washed 3 times with TBST/CaCl2 prior to adding anti-thioredoxin or anti-CD36 polyclonal antibody (1:1000) for 1h at 22°C. HRP-anti-rabbit IgG was then added for 1h at 22°C. Bound antibody was detected using the TMB-ELISA reagent (Pierce) reading absorbance at 450nM with a SpectraMax 190 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices).

Mass Spectrometry

Protein bands were cut from SDS-PAGE gels, washed/destained in 50% ethanol, 5% acetic acid and then dehydrated in acetonitrile. The proteins were then reduced with dithiothreitol and alkylated with iodoacetamide prior to the overnight in-gel digestion at 22°C with Lys-C (0.1ng/μl) in 50mM ammonium bicarbonate. The peptides were then extracted from the polyacrylamide in two aliquots of 30μl 50% acetonitrile with 5% formic acid. These extracts were combined, evaporated to <10μl, and resuspended in 1% acetic acid to a final volume of ∼30μl for LC-MS analysis using a self-packed 9cm × 75μm Phenomenex Jupiter C18 reversed-phase capillary chromatography column and a Finnigan LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer system operated at 2.5 kV. Chromatograms for each of these peptides were plotted and the peak areas determined manually with the program Qual Browser (Thermal Scientific). The pT92/T92 ratio was estimated by the observed peak area ratio for these peptides.

Results

CD36 CLESH domain phosphorylation blocks binding to recombinant TSR domains

To confirm that CD36 ecto-domain phosphorylation blocks thrombospondin-1 binding and determine if phosphorylation of the CLESH domain by itself impacts binding of small TSR-containing peptides we prepared a recombinant “extended” CLESH domain beginning at a.a. 81 that includes the Thr92-X-Arg PKC target motif (Fig. 1A). As shown in the western blot in Fig. 1B the extended CLESH domain, but not a mutant substituting Ala for Thr at position 92, was readily phosphorylated by incubation with PKCα in vitro. Phosphorylation at Thr92 was confirmed and quantified by mass spectrometry. A dose response and time course study revealed that ∼25% of the total CD36 protein was phosphorylated at maximum (data not shown), but since phosphorylation reduces the efficiency of peptide ionization by at least half 15-16, this percentage is likely an underestimate by at least two-fold.

Figure 1.

Extended CD36 CLESH domain can be phosphorylated on Thr92 by PKCα. A. Schematic representations of CD36 showing the CLESH domain and PKC phosphorylation site (Thr92); and the recombinant thioredoxin/extended CLESH domain fusion protein. TM indicates transmembrane domains. B. Wild type and T92A mutated fusion proteins were incubated with 1ng/μl PKCα at 37°C for 16h and then 5μg were analyzed by western blot with an anti-phospho-Threonine antibody. Blots were re-probed with anti-thioredoxin antibody as loading controls. The blot shows that the wild-type (WT) extended CLESH domain was phosphorylated, while the T92A mutant or recombinant thioredoxin alone were not. Blots are representative of n=3.

The extended CLESH domain peptide retained capacity to bind immobilized thrombospondin-1 as assessed in a solid phase binding assay (Fig. 2A). The recombinant thioredoxin tag alone did not bind thrombospondin-1, demonstrating specificity. As with intact CD36, binding to the extended CLESH domain peptide was Ca++-dependent. Figure 2B shows that soluble thrombospondin-1 also bound to the extended CD36 CLESH domain when the latter was immobilized. To determine if inhibition of thrombospondin-1 binding by CD36 phosphorylation was mediated by interactions outside of the TSR and CLESH domains we studied binding of a recombinant peptide made up only of the second and third TSR domains to the recombinant extended CLESH domain. As shown in Fig. 2C, the non-phosphorylated recombinant extended CLESH protein bound immobilized TSR2/3 in a concentration dependent manner. Binding of the phosphorylated protein was significantly reduced, but was restored by pre-treatment with alkaline phosphatase to remove most of the phosphorylation (Fig. 2D). To determine whether inhibition of binding correlates with level of CD36 phosphorylation we mixed non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated proteins at 1:0, 1:1, 1:2, and 0:1 ratios to create mixtures containing 0, ∼25%, ∼33% and ∼50% phosphorylated CLESH (Fig. 2E). As shown in Fig. 2F, at the highest input concentration, binding of CD36 CLESH proteins was inversely proportional to the degree of phosphorylation.

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation of extended CD36 CLESH domain blocks binding of thrombospondin type I repeats (TSR). A. Recombinant CD36 extended CLESH domain binds thrombospondin-1. CLESH domain fusion protein (10μg/ml) or thioredoxin control were incubated in TBS containing 1mM CaCl2 with or without 5mM EDTA in microtiter wells on which thrombospondin-1 had been adsorbed. After washing, bound proteins were detected by colorimetric assay using specific antibodies and HRP-conjugated second antibodies. Significant calcium-dependent binding of the CLESH domain was seen. Thioredoxin did not bind, demonstrating specificity. B. Thrombospondin-1 binds immobilized recombinant CD36 extended CLESH domain. Thrombospondin-1 (10μg/ml) was incubated as in panel A in wells on which CLESH domain fusion proteins or thioredoxin control had been absorbed. C. Phosphorylation of CD36 extended CLESH domain inhibits binding to a recombinant peptide containing the second and third TSR domains (TSR2/3). TSR2/3 protein was adsorbed on microtiter wells and then untreated fusion proteins (◆), or proteins exposed to PKCα as in Fig. 1 (■), or proteins exposed to PKCα followed by exposure to alkaline phosphatase (▲) were added to the wells at concentrations 0 - 10μg/ml. Bound fusion proteins were detected as in panel A. D. Phosphorylation levels of extended CLESH domain proteins. Fusion proteins were either exposed to PKCα as in Fig. 1 or PKCα followed by purified alkaline phosphatase (AP) then analyzed by western blot with an anti-phospho-Threonine antibody. Blots were re-probed with anti-thioredoxin as a loading control. NT represents untreated fusion protein. E. Non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated fusion proteins were mixed at 4 different ratios. Mixtures were analyzed by western blot as in panel D. F. Binding of TSR2/3 to CD36 extended CLESH domain inversely correlates with level of phosphorylation. Mixtures of non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated extended CLESH domain prepared as in Panel E were assayed for binding to immobilized TSR2/3 as in panel C. All blots are representative of n=3.

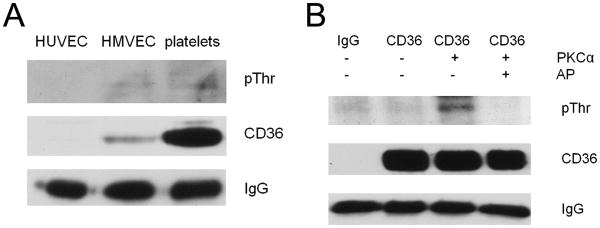

Basal levels of cellular CD36 phosphorylation in vivo are low

To determine basal phosphorylation levels in vivo, CD36 was immunoprecipitated from human MVEC and platelets and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblot with an anti-phospho-threonine antibody. HUVEC were used as negative control, since they do not express CD36. As shown in Fig. 3A, phosphorylated CD36 was detected in both platelets and MVEC but in both cases the signal was very weak compared to that seen with recombinant CD36 peptides. While the expression level of CD36 in human platelets is much higher than in MVEC, the signal of phosphorylated CD36 is similar, suggesting that the proportion of phosphorylated CD36 is higher in MVEC than in platelets. Since basal CD36 phosphorylation levels are low, we tested whether they could be increased by in vitro phosphorylation; i.e. whether full length native CD36 retained the capacity to be phosphorylated. CD36 was immuno-precipitated from platelets and then incubated with PKCα in vitro for 1h. As shown in Fig. 3B, this significantly increased the level of phosphorylation. The PKC phosphorylated CD36 was then treated with alkaline phosphatase for 1h to show that phosphorylation could be reversed. These results indicate that the “default” phosphorylation level of CD36 in cells is very low, but that there is a capacity to increase phosphorylation.

Figure 3.

Cellular CD36 phosphorylation levels are low. A. CD36 was immunoprecipitated from human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC), MVECs and platelets and phosphorylation was detected by western blot with an anti-phospho-Thr antibody. Blots were also probed with antibodies to CD36 and IgG as loading controls. B. Cellular CD36 was immunoprecipitated from human platelets and then incubated with vehicle control or PKCα at 1ng/μl for 1h. An aliquot of PKC-treated CD36 was then exposed to alkaline phosphatase at 0.2u/μl for 1h. CD36 phosphorylation was then detected by western blot as in panel A. Blots are representative of n=3.

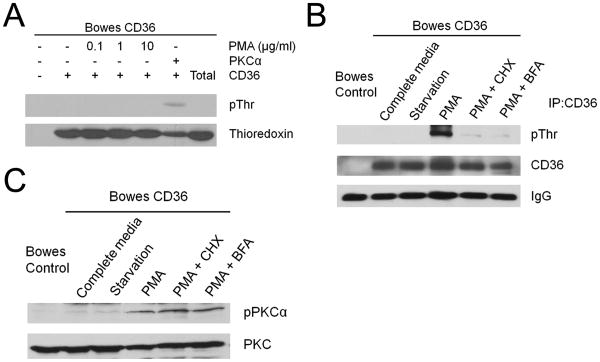

Cellular CD36 phosphorylation can be increased by PMA

To determine the impact of intracellular PKC activation on CD36 phosphorylation we treated cells from a well-characterized Bowes melanoma cell line stably transfected with CD36 cDNA with a broadly active PKC activator, PMA. We used melanoma cells rather than MVEC in these experiments because previous studies showed that PMA induced dramatic and rapid transcriptional suppression of CD36 expression in MVEC 17. Bowes cells were exposed to 0.01μg/ml, 0.1μg/ml or 1μg/ml PMA, and PKCα activity was confirmed by western blot using an antibody to phospho-PKCα (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, prior to PMA treatment levels of phosphorylated CD36 were very low and treatment with serum starvation or staurosporine, a PKC inhibitor, had no significant impact. CD36 phosphorylation, however, increased in a dose and time dependent manner upon exposure of the cells to PMA (Figure 4B and 4C), with a maximum effect seen at 0.1μg/ml and a modest reduction seen at higher concentrations (1μg/ml). PMA-induced CD36 phosphorylation was first detected after 2h exposure and increased further after 4h. Interestingly, PMA did not induce CD36 phosphorylation in platelets or MVEC, but these results are difficult to interpret since prolonged PMA treatment suppressed PKC expression in these cells (not shown). On the other hand, PMA induced CD36 phosphorylation in THP-1 monocytic cells (Figure 4D). In these cells PMA treatment was associated with prolonged PKC activation (rather than down-regulation) and with up-regulation of CD36 expression.

Figure 4.

Cellular CD36 phosphorylation is increased by treatment with PMA. A. PMA activates PKCα kinase in Bowes cells. CD36-transfected Bowes melanoma cells were incubated for 16h in low serum media (1%FBS) and then treated with different concentrations of PMA for 4h. PKCα was then immunoprecipitated with anti-PKCα IgG and analyzed by western blot with an antibody specific for the PKCα auto-phosphorylation site. B. CD36 transfected Bowes melanoma cells were treated with PMA as in panel A for 4h or with 1μM staurosporine. CD36 was then immunoprecipitated and phosphorylation state assessed by western blot as in Fig. 3. C. CD36 transfected Bowes melanoma cells were treated with 0.1μg/ml PMA for 1 to 4 h. CD36 phosphorylation was then assessed by western blot as above. D. THP-1 cells were treated with 0.1μg/ml PMA for 1 to 4 h. CD36 phosphorylation was then assessed by western blot as above. E. CD36 transfected Bowes melanoma cells were treated with 0.1μg/ml PMA, 5μM cAMP or 10μM PS48 for 4 h. CD36 phosphorylation was then assessed by western blot as above. Blots are representative of n=3.

To test whether activation of other kinases could also induce CD36 phosphorylation Bowes cells were exposed to cAMP and PS48, which are activators of PKA and PDK-1 respectively. As shown in figure 4E, cAMP had did not influence either PKC activation or CD36 phosphorylation. PS48, however, induced CD36 phosphorylation equivalently to PMA, presumably related to the ability of PKD-1 to activate PKC.

New protein synthesis and trafficking through Golgi are required for PMA-induced CD36 phosphorylation

It is not known if CD36 phosphorylation occurs in an intracellular compartment or extracellularly. To test whether extracellular or cell-surface associated kinase activity was induced by PMA, Bowes cells were treated with PMA for 4h and then the cells or post-culture medium were incubated with recombinant CD36 extended CLESH domain peptide (1μM) and 0.2mM ATP for 1h. While the peptide was readily phosphorylated by addition of exogenous PKCα (1ng/μl), no phosphorylation was detected when the peptide was incubated with cells (Fig. 5A) or postculture medium (not shown). These results suggest that CD36 phosphorylation is not the result of PMA-induced expression of a secreted or surface-associated kinase. The prolonged time required to see an increase in CD36 phosphorylation after PMA treatment suggests that new protein synthesis could be involved in this process and it may be newly synthesized CD36 that is phosphorylated in response to PMA-activated PKC. To test this hypothesis we exposed Bowes cells to chemical inhibitors of protein synthesis (100μg/ml cycloheximide) or ER-Golgi trafficking (5μg/ml Brefeldin A) concomitantly with PMA. While PMA induced robust CD36 phosphorylation (Fig. 5B), both cycloheximide and Brefeldin A inhibited the induction almost completely. The inhibitory effect was not due to a change in PKCα activity, as shown in Fig. 5C. These data suggest that only newly synthesized CD36 is phosphorylated and that phosphorylation occurs after ER to Golgi transit.

Figure 5.

Protein synthesis and ER to Golgi trafficking are required for PMA induced CD36 phosphorylation. A. CD36 transfected Bowes melanoma cells were treated with PMA as in panel 4A for 4h and then incubated with 1μM recombinant CD36 extended CLESH domain and 0.2mM ATP for 1h. After incubation, the peptide was purified on 25μl Ni++ beads and then analyzed by western blot with an anti-phospho-Thr antibody. Blots were re-probed with anti-thioredoxin antibody as loading controls. As a positive control (lane 6) a similar amount of CD36 peptide was incubated with exogenous PKCα. The last lane (Total) shows the amount of recombinant peptide added prior to Ni++ bead pull down and shows near quantitative recovery. B. CD36-transfected Bowes cells were incubated for 16h in low serum media and then treated for 4h with 0.1μg/ml PMA along with either 100μg/ml cycloheximide or 5ng/ml Brefeldin A. CD36 phosphorylation was then assessed by western blot as in Fig. 3. C. Cells treated as in Panel A were assessed for PKAα activity in whole cell lysates by western blot with phospho-PKCα IgG. Blots were re-probed with an antibody to total PKCα as a loading control. Blots are representative of n=3.

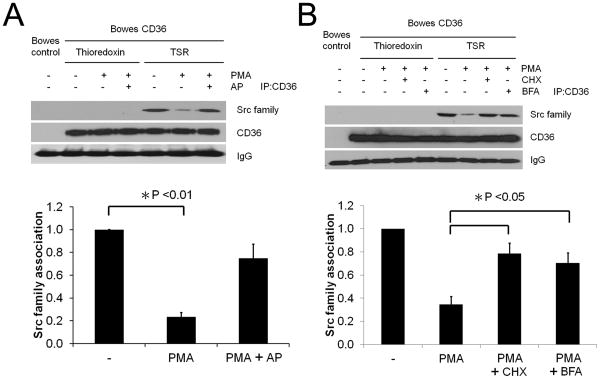

PMA-induced CD36 phosphorylation blunts TSR-mediated recruitment of Src family proteins to CD36

A proximal event in CD36-mediated cell signaling is ligand-dependent recruitment of specific Src-family kinases to a CD36-containing multi-protein signaling complex 6. To determine whether PMA-induced CD36 phosphorylation influences CD36 signaling functions we assessed TSR-induced recruitment of Src family proteins to CD36. CD36 expressing Bowes melanoma cells were exposed to 0.1μg/ml PMA for 4h and then treated with 100nM TSR or control protein, thioredoxin, for 15min prior to CD36 immunoprecipitation. CD36 non-expressing cells were also studied as a control. As shown in Fig. 6A, Src family protein(s) were recruited to the CD36 signaling complex after exposure to TSR but not thioredoxin or PMA. The amount of Src protein recruited to the complex after TSR exposure was reduced by ∼75% in cells treated with PMA (p < 0.01). Exposure of the cells to alkaline phosphatase (40u/ml) for 1h after PMA treatment restored TSR-induced Src protein association with CD36. To test whether cycloheximide and Brefeldin A also restored TSR-induced Src protein association with CD36, Bowes cells were exposed to 0.1μg/ml PMA along with cycloheximide or Brefeldin A for 4h and then treated with 100nM TSR or control protein, thioredoxin, for 15min prior to CD36 immunoprecipitation. As shown in figure 6B, cycloheximide and Brefeldin A both restored TSR-induced Src protein association with CD36. These data show that PMA-induced CD36 phosphorylation changed the signaling potential of CD36 in response to TSR.

Figure 6.

PMA-induced CD36 phosphorylation inhibits TSR-mediated Src recruitment to CD36. A. CD36 transfected Bowes melanoma cells were incubated for 16h in low serum media and then treated for 4h with 0.1μg/ml PMA or vehicle control. Some cells were then treated for 1h with 40u/ml alkaline phosphatase (AP) or vehicle control. Cells were then exposed to 100nM recombinant TSR2/3 or thioredoxin control for 15min. CD36 was then immunoprecipitated and the precipitates were analyzed by western blot with an antibody to Src family proteins. Blots were re-probed with anti-CD36 antibodies. Blots were scanned and the amount of co-precipitated Src was normalized to total CD36. B. CD36 transfected Bowes melanoma cells were incubated for 16h in low serum media and then treated for 4h with 0.1μg/ml PMA along with either 100μg/ml cycloheximide or 5ng/ml Brefeldin A. Cells were then exposed to 100nM recombinant TSR2/3 or thioredoxin control for 15min. Src family association was then assessed by western blot and analyzed as in panel A. C) Cells prepared as in Panel B were analyzed by western blot using antibodies to phospho-PKCα (upper blot). Blots were then stripped and re-probed with an antibody to total PKC (lower blot). All blots are representative of n=3.

Discussion

Although CD36 phosphorylation is potentially important as a modulator of ligand binding 7-8, the mechanisms by which cells accomplish and regulate ectodomain phosphorylation as well as the mechanism by which phosphorylation influences thrombospondin binding are not known. In this manuscript we shed light on all of these issues. We used recombinant peptides to show that inhibition of thrombospondin binding to phospho-CD36 is an inherent property of the two small peptide domains involved in the direct binding interaction – CLESH and TSR. TSR domains are highly conserved structures found on many CD36-binding proteins 14, 18-19. Binding of these proteins to CD36 is mediated by interaction between the CLESH domain of CD36 with the TSR domain(s) 11-12, 20-23. We found that phosphorylation of a recombinant CD36 CLESH domain extended by only a few amino acids to include the PKC substrate site blocked its ability to bind recombinant TSR2/3 in a manner that was proportional to the degree of phosphorylation. Thrombospondin-1 is a large multi-domain protein and it is possible that the blocking effect of CD36 phosphorylation could be mediated by interactions between the phosphorylated residue and other domains of thrombospondin-1, or that phosphorylation disrupts CD36 structure in such a way to make the CLESH domain inaccessible. Recapitulating the inhibitory effect with small recombinant peptides strongly suggests that other domains are not involved and that phosphorylation directly impeded TSR binding to CLESH, perhaps by steric or charge hindrance. These data also suggest that binding of other anti-angiogenic TSR containing proteins to CD36 could also be modulated by CD36 phosphorylation.

The low basal levels of platelet and MVEC phosphorylation seen in our studies are consistent with the well-described robust CD36-dependent anti-angiogenic and pro-thrombotic effects of TSR-proteins in vitro and in vivo 3-4, 6, 23. Our findings that inhibition of TSR binding correlated with the level of phosphorylation of CD36 and that basal levels of cellular CD36 phosphorylation were very low indicates that cellular up-regulation of CD36 phosphorylation could be an important mechanism for dampening responses to TSR proteins. Indeed we identified a PKC-mediated pathway that significantly increased CD36 phosphorylation and decreased functional response to TSR in CD36 transfected melanoma cells. We speculate that growth factors or cytokines released from tumor cells or from non-malignant cells within the tumor microenvironment could activate this pathway in the tumor microvasculature and thus decrease the sensitivity of endothelial cells to endogenous anti-angiogenic factors, such as thrombospondin-1. Conversely, inhibiting this pathway in tumor endothelial cells could be a potential mechanism to overcome loss of responsiveness to TSR-mediated anti-angiogenesis. Unfortunately, we were unable to test whether this pathway influences angiogenesis in vivo, because the PKC activator PMA down-regulates CD36 expression in MVEC.

While PMA is known to suppress CD36 expression in MVEC and induce CD36 expression in monocytes and T-cells 17, 24-26, we did not see a significant change of CD36 expression in Bowes melanoma cells after 4h treatment and thus the increase seen in CD36 phosphorylation was not due to a proportional increase in total CD36 expression. Our studies of PDK-1, which is an upstream activator of PKC, are consistent with studies on the role of PKC in platelet CD36 phosphorylation7, and support the hypothesis that PMA-induced CD36 phosphorylation is mediated by activation of PKC. PDK-1, like PMA activates PKC family members broadly 27, thus whether CD36 phosphorylation is mediated by a specific PKC isoform remains to be determined. Although cAMP had been shown to induce CD36 phosphorylation in platelets by activating an ecto-PKA activity 9, it did not induce CD36 phosphorylation in Bowes cells.

Cellular mechanisms of CD36 ectodomain phosphorylation remain poorly understood. That significant up-regulation of CD36 phosphorylation in Bowes cells was not seen until ∼4 hours after exposure to PMA even though activation of PKC was seen in minutes suggests an indirect mechanism. Since there was no detectable kinase activity in either Bowes cell post culture media or on Bowes cell surfaces at the point where CD36 phosphorylation was detected, it is unlikely that PKC directly phosphorylates CD36 on the plasma membrane, or that the mechanism reported for platelets; i.e. induction of a surface-associated enzyme with protein kinase A-like activity is present in Bowes cells 9. In MVEC and platelets, where PMA did not enhance CD36 phosphorylation, PKC expression was dramatically suppressed by prolonged PMA exposure (not shown), suggesting that sustained PKC activity is necessary for CD36 phosphorylation. In contrast to MVEC and platelets, the two cellular systems in which we observed up-regulation of phosphorylation - transfected Bowes cells and PMA-stimulated THP-1 cells - are both characterized by high levels of CD36 gene transcription and protein synthesis. We thus hypothesized that CD36 phosphorylation occurs on newly synthesized protein and indeed found that phosphorylation was blocked by inhibiting new protein synthesis. Furthermore, inhibition by brefeldin A suggests that phosphorylation occurs in an intracellular post-ER compartment.

In summary, we showed with in vitro assays that CD36 phosphorylation directly inhibits binding of TSR domains to CD36 CLESH domains and provide convincing in vivo evidence that low basal levels of cellular CD36 phosphorylation can be enhanced in the setting of robust CD36 synthesis by activating an intracellular PKC – mediated signaling pathway. CD36 phosphorylation occurs intracellularly on newly synthesized protein in a post ER compartment. By showing that PMA-induced CD36 phosphorylation blunted TSR-dependent assembly of an intracellular CD36 signaling complex we suggest that up-regulation of CD36 phosphorylation may be a mechanism to desensitize cellular responses to TSR-mediated signals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Belinda Willard, Ph.D. and the Proteomics Core Laboratory of Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation for help with analysis of mass spectrometry data.

Source of Funding: This project was supported by National Institute of Health grant HL085718 (to R.L.S.).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Silverstein RL, Febbraio M. Cd36, a scavenger receptor involved in immunity, metabolism, angiogenesis, and behavior. Sci Signal. 2009;2:re3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.272re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clemetson KJ, Pfueller SL, Luscher EF, Jenkins CS. Isolation of the membrane glycoproteins of human blood platelets by lectin affinity chromatography. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1977;464:493–508. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(77)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverstein RL, Baird M, Lo SK, Yesner LM. Sense and antisense cdna transfection of cd36 (glycoprotein iv) in melanoma cells. Role of cd36 as a thrombospondin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16607–16612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson DW, Pearce SF, Zhong R, Silverstein RL, Frazier WA, Bouck NP. Cd36 mediates the in vitro inhibitory effects of thrombospondin-1 on endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:707–717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asch AS, Barnwell J, Silverstein RL, Nachman RL. Isolation of the thrombospondin membrane receptor. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1054–1061. doi: 10.1172/JCI112918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jimenez B, Volpert OV, Crawford SE, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL, Bouck N. Signals leading to apoptosis-dependent inhibition of neovascularization by thrombospondin-1. Nat Med. 2000;6:41–48. doi: 10.1038/71517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asch AS, Liu I, Briccetti FM, Barnwell JW, Kwakye-Berko F, Dokun A, Goldberger J, Pernambuco M. Analysis of cd36 binding domains: Ligand specificity controlled by dephosphorylation of an ectodomain. Science (New York, NY. 1993;262:1436–1440. doi: 10.1126/science.7504322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho M, Hoang HL, Lee KM, Liu N, MacRae T, Montes L, Flatt CL, Yipp BG, Berger BJ, Looareesuwan S, Robbins SM. Ectophosphorylation of cd36 regulates cytoadherence of plasmodium falciparum to microvascular endothelium under flow conditions. Infection and immunity. 2005;73:8179–8187. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8179-8187.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatmi M, Gavaret JM, Elalamy I, Vargaftig BB, Jacquemin C. Evidence for camp-dependent platelet ectoprotein kinase activity that phosphorylates platelet glycoprotein iv (cd36) The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:24776–24780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guthmann F, Maehl P, Preiss J, Kolleck I, Rustow B. Ectoprotein kinase-mediated phosphorylation of fat/cd36 regulates palmitate uptake by human platelets. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1999–2003. doi: 10.1007/PL00012522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crombie R, Silverstein R. Lysosomal integral membrane protein ii binds thrombospondin-1. Structure-function homology with the cell adhesion molecule cd36 defines a conserved recognition motif. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4855–4863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frieda S, Pearce A, Wu J, Silverstein RL. Recombinant gst/cd36 fusion proteins define a thrombospondin binding domain. Evidence for a single calcium-dependent binding site on cd36. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2981–2986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverstein RL, Leung LL, Harpel PC, Nachman RL. Platelet thrombospondin forms a trimolecular complex with plasminogen and histidine-rich glycoprotein. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1985;75:2065–2073. doi: 10.1172/JCI111926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan K, Duquette M, Liu JH, Dong Y, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Lawler J, Wang JH. Crystal structure of the tsp-1 type 1 repeats: A novel layered fold and its biological implication. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:373–382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janek K, Wenschuh H, Bienert M, Krause E. Phosphopeptide analysis by positive and negative ion matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:1593–1599. doi: 10.1002/rcm.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig AG, Engstrom A, Bennich H, Hoffmann-Posorske E, Meyer HE. Plasma desorption mass spectrometry of phosphopeptides: An investigation to determine the feasibility of quantifying the degree of phosphorylation. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1991;20:565–574. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200200910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren B, Hale J, Srikanthan S, Silverstein RL. Lysophosphatidic acid suppresses endothelial cell cd36 expression and promotes angiogenesis via a pkd-1-dependent signaling pathway. Blood. 2011;117:6036–6045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutter H, Vogel BE, Plenefisch JD, Norris CR, Proenca RB, Spieth J, Guo C, Mastwal S, Zhu X, Scheel J, Hedgecock EM. Conservation and novelty in the evolution of cell adhesion and extracellular matrix genes. Science (New York, NY. 2000;287:989–994. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverstein RL, Febbraio M. Cd36-tsp-hrgp interactions in the regulation of angiogenesis. Current pharmaceutical design. 2007;13:3559–3567. doi: 10.2174/138161207782794185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asch AS, Silbiger S, Heimer E, Nachman RL. Thrombospondin sequence motif (csvtcg) is responsible for cd36 binding. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1992;182:1208–1217. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91860-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klenotic PA, Huang P, Palomo J, Kaur B, Van Meir EG, Vogelbaum MA, Febbraio M, Gladson CL, Silverstein RL. Histidine-rich glycoprotein modulates the anti-angiogenic effects of vasculostatin. The American journal of pathology. 2010;176:2039–2050. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaur B, Cork SM, Sandberg EM, Devi NS, Zhang Z, Klenotic PA, Febbraio M, Shim H, Mao H, Tucker-Burden C, Silverstein RL, Brat DJ, Olson JJ, Van Meir EG. Vasculostatin inhibits intracranial glioma growth and negatively regulates in vivo angiogenesis through a cd36-dependent mechanism. Cancer research. 2009;69:1212–1220. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simantov R, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL. The antiangiogenic effect of thrombospondin-2 is mediated by cd36 and modulated by histidine-rich glycoprotein. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yesner LM, Huh HY, Pearce SF, Silverstein RL. Regulation of monocyte cd36 and thrombospondin-1 expression by soluble mediators. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 1996;16:1019–1025. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han S, Sidell N. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated-receptor gamma (ppargamma) independent induction of cd36 in thp-1 monocytes by retinoic acid. Immunology. 2002;106:53–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lubick K, Jutila MA. Lta recognition by bovine gammadelta t cells involves cd36. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2006;79:1268–1270. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1005616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toker A. Pdk-1 and protein kinase c phosphorylation. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ. 2003;233:171–189. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-397-6:171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]