Abstract

With the possible introduction of exon skipping therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy, it has become increasingly important to know the role of each exon of the dystrophin gene to protein expression, and thus the phenotype. In this report, we present two related men with an unusually mild BMD associated with an exon 26 deletion. The proband, a 23-year-old man, had slightly delayed motor milestones, walking 1½ years old. He had no complaints of muscle weakness, but had muscle pain. Clinical examination revealed no muscle wasting or loss of power, but his CK was 1500-7000 U/l. Muscle biopsy showed dystrophic changes. He had comorbidity with dystonia, slight mental retardation, low stature and neuropathy. The brother of the proband's mother came to medical attention when he was 43 years old. He complained about muscle pain. On examination, a MRC grade 4+ hip extention palsy and a discrete calf hypertrophy was noted. Creatine kinase was normal or raised maximally to 500U/l. The muscle biopsy was myopathic with increased fiber size variation and many internal nuclei, but no dystrophy. No comorbidity was found. In both cases, western blot showed a reduced dystrophin band. Genetic evaluation revealed a deletion of exon 26 of the dystrophin gene in both. This is the first description of patients with a exon 26 deletion of the dystrophin gene. Assuming the proband's comorbidity is unrelated, exon 26 deletion results in a very mild phenotype. This might be of interest in planning exon skipping therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. This report also shows that BMD may present with a normal CK.

Key words: BMD, dystrophin, deletion, exon 26

Introduction

No curative treatment is available for the two dystrophinopathies, Becker and Duchenne muscular dystrophies. In 1995, low-dose steroid treatment was shown to diminish deterioration of muscle strength in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (1), and is now routinely offered to many, preferentially ambulatory, patients. Symptomatic treatment such as ventilatory support and physiotherapy has also led to improvements of life quality and survival. In spite of this progress, however, the dystrophinopathies progress relentlessly and typically result in severe disability. A promising new treatment is exon-skipping therapy which is based on converting an "out-of-frame" mutation into an "in-frame" mutation, and thus transforming a severe Duchenne phenotype to a mild Becker phenotype. Phase 1-2 trials are ongoing to investigate the feasibility of exon skipping for Duchenne (2, 3). With the possible introduction of exon skipping therapy, it has become increasingly important to know the exact role of each exon of the dystrophin gene on protein expression, and thus the phenotype.

In this report, we present two related men with an unusually mild Becker muscular dystrophy phenotype associated with a novel exon 26 deletion.

Methods

After informed consent, we studied the phenotype of the index person and his maternal uncle. The disease history was obtained in a formal interview and clinical examination was carried out with estimation of muscle strength and evaluation of muscle bulk. Needle biopsies were performed in the lateral vastus muscle. Multiplex western blots were performed as described by Anderson (4). An electrocardiogram and echocardiography were performed in both patients.

Results

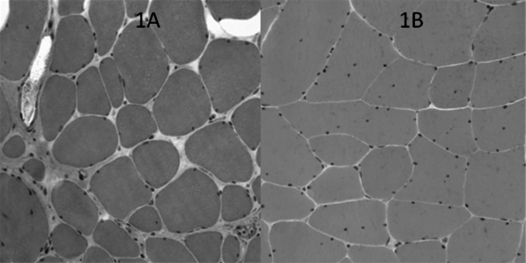

The proband, a 23-year-old man, had slightly delayed motor milestones, walking 1½ years old. He had no complaints of muscle weakness, but had muscle pain. Clinical examination, at the age of 16 years, revealed no muscle wasting or loss of power, but his creatine kinase was increased to 1500-7000 U/l (< 400). His muscle biopsy showed dystrophic changes (Fig. 1A). He had co-morbidity with segmental dystonia including torticollis, slight mental retardation, low stature and axonal neuropathy verified by ENG. His dystonia was treated with Clonazepam, Orphenadrin and botulinum injections. At age 20, he still had preserved muscle strength and bulk.

Figure 1.

HE stained muscle section from the vastus lateralis muscle. 1A is from the proband, showing marked fibre size variability, central nuclei and fibrosis. 1B is from his maternal uncle, showing milder changes without fibrosis.

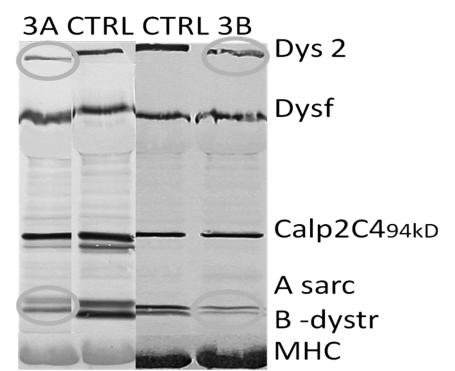

The brother of the proband's mother came to medical attention when he was 43 years old. He complained about muscle pain. On examination, a MRC grade 4+ hip extension palsy and a discrete calf hypertrophy (Fig. 2) was noted. Creatine kinase was normal or increased to maximally 500 U/l. The muscle biopsy was myopathic with increased fiber size variation and multiple internal nuclei, but no dystrophic changes as seen in his nephew (Fig. 1B). No co-morbidity was found. In both cases, western blot revealed a marginally reduced size of dystrophin, with a severely decreased expression level to less than 5% of normal. α-Sarcoglycan, β-dystroglycan, Calpain and merosin were down-regulated in parallel (Fig. 3). Genetic evaluation, through MPLA and direct PCR, revealed a deletion of exon 26, (c.3433-?_3603+?del) of the dystrophin gene in both patients. The mutation is predicted to induce an in-frame transcript.

Figure 2.

The maternal uncle of the proband showing slight hypertrophy of his calves.

Figure 3.

Western blots of the proband (3A) and his maternal uncle (3B). The blots show weak dystrophin bands with a slightly shorter dystrophin than the wild-type. α-Sarcoglycan and β-dystroglycan are down-regulated secondary to the dystrophin loss.CTRL, control.

Discussion

Mutations involving exon 26 have been described several times (5), most often leading to a Duchenne phenotype. These mutations introduce premature stop codons (6-8) or disrupts correct reading, all leading to loss of functional dystrophin protein. Here we present the first report of patients hemizygous for a deletion in exon 26. The deletion is predicted to result in an "in-frame" transcript of the dystrophin gene. Exon 26 is part of the central rod domain of dystrophin that connects the actin at the sarcomer to the glycoprotein complex at the membrane. The exact function of exon 26 or the central rod domain is not entirely understood, and the consequence of exon 26 deletion can therefore not be predicted theoretically. Assuming the proband's co-morbidity is unrelated to the dystrophinopathy, our findings suggest that exon 26 deletion results in a very mild phenotype.

According to human genome mutation database (HGMD) 23 different point mutations or smaller insertion/ deletion mutations are located in exon 26 all but a few resulting in a Duchenne phenotype. Our finding implicates that patients with these mutations could potentially benefit from an exon-skipping therapy in which exon 26 is skipped, with the aim of ameliorating the phenotype from Duchenne to a Becker muscular dystrophy. Our finding has therefore potentially positive therapeutic implications for a selection of Duchenne patients.

Another interesting finding is the normal CK in one of our subjects. We have previously reported normal CK levels with deletion of exon 16 of the dystrophin gene (9). The index person was an asymptomatic 26 year old woman who volunteered to donate reference material for genetic analysis. Thus the finding of the exon 16 deletion was accidental. Her 60-year-old father also was hemizygous for the same deletion and like his daughter had normal CK, muscle biopsy and clinical examination. Normal CK and clinical evaluation have also been described with deletion of exons 49-51 in a grandfather, whereas the younger members of the family were symptomatic with elevated CK (10). Normal CK level in asymptomatic individuals with aberrations of the dystrophin gene is therefore known. In contrast, normal CK in symptomatic Becker patients have not been reported before. This finding has important implications for clinical practice, because a raised CK normally is considered obligatory for Becker muscular dystrophy.

References

- 1.Backman E, Henriksson KG. Low-dose prednisolone treatment in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 1995;5:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(94)00048-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goemans NM, Tulinius M, Akker JT, et al. Systemic administration of PRO051 in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1513–1522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu QL, Yokota T, Takeda S, et al. The status of exon skipping as a therapeutic approach to duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol Ther. 2011;19:9–15. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson LV, Davison K. Multiplex Western blotting system for the analysis of muscular dystrophy proteins. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1017–1022. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65354-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artsma-Rus A, Deutekom JC, Fokkema IF, et al. Entries in the Leiden Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutation database: an overview of mutation types and paradoxical cases that confirm the reading-frame rule. Muscle Nerve. 2006;34:135–144. doi: 10.1002/mus.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garwal-Mawal A, Vanasse M, Simard LR, et al. Novel 3678delA mutation in exon 26 of the dystrophin gene causing Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Mutat. 1998;(Suppl 1):S23–S24. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380110108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilton SD, Chandler DC, Kakulas BA, et al. Identification of a point mutation and germinal mosaicism in a Duchenne muscular dystrophy family. Hum Mutat. 1994;3:133–140. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380030208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulman DE, Gangopadhyay SB, Bebchuck KG, et al. Point mutation in the human dystrophin gene: identification through western blot analysis. Genomics. 1991;10:457–460. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz M, Duno M, Palle AL, et al. Deletion of exon 16 of the dystrophin gene is not associated with disease. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:205–205. doi: 10.1002/humu.9477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saengpattrachai M, Ray PN, Hawkins CE, et al. Grandpa and I have dystrophinopathy?: approach to asymptomatic hyperCKemia. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;35:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]