Abstract

Substantial progress has been made in reducing HIV among injection drug users (IDUs) in the United States, despite political and social resistance that reduced resources and restricted access to services. The record for HIV prevention among noninjecting drug users is less developed, although they are more numerous than IDUs. Newer treatments for opiate and alcohol abuse can now be integrated into primary HIV care; treatment for stimulant abuse is less developed. All drug users present challenges for newer HIV prevention strategies (eg, “test and treat,” nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis and pre-exposure prophylaxis, contingency management, and conditional cash transfer). A comprehensive HIV prevention program that includes multicomponent, multilevel approaches (ie, individual, network, structural) has been effective in HIV prevention among IDUs. Expanding these approaches to noninjecting drug users, especially those at highest risk (eg, minority men who have sex with men) and incorporating these newer approaches is a public health priority.

Keywords: HIV, noninjection drug use, injection drug use, prevention, contingency management, treatment, epidemiology

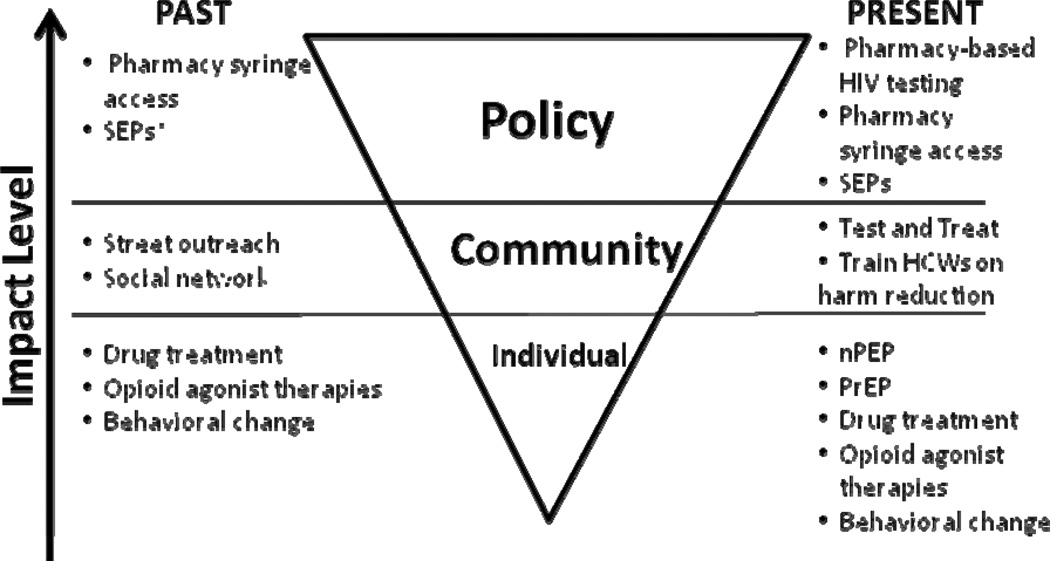

National data has consistently estimated that 20.1 million Americans use illicit drugs.1 Of those, roughly 1.2 million inject drugs, a practice that has been recognized for its role in HIV transmission, accounting for 11% of HIV infections.1,2 Among injection drug users (IDUs) in the United States, the HIV rate has been estimated to be 28%.3 Addressing the challenge of the HIV epidemic in injectors was made difficult by powerful political and social resistance (eg, zero tolerance campaigns) that dampened access to important resources for drug users.4 However, during this period, the US Public Health Services developed and disseminated a hierarchy of prevention.2,5–7 Briefly, its first tier called for abstinence, which could be facilitated through treatment for drug abuse. For those IDUs who could not or would not quit drug use, a second tier advised using sterile syringes and disposing of them safely. The third tier, a recommendation applicable when sterile injection equipment was unavailable, was disinfection with bleach.5,8 These messages have been successfully implemented by combining interventions at individual, community, and policy levels9 that promoted education through community outreach as well as HIV testing; behavioral interventions10; drug abuse treatment,11 including opioid agonist therapies12; and syringe exchange programs,13 which were later supplemented by providing for syringe access through pharmacies14,15 (Figure 1). Concerns about the potential for syringe access to encourage initiation of drug use among youth and to increase drug use, needle sharing, and crime, proved unfounded.13 Even before the availability of antiretroviral therapy, HIV prevalence and incidence among injection drug users declined.16–18 The purpose of this brief review is to discuss newer approaches to HIV prevention strategies and potential implementation challenges for prevention both among noninjecting drug users (NIDUs), sometimes mistakenly referred to as “recreational users,” who have received insufficient attention for HIV prevention, and among IDUs—framed within consideration of hurdles encountered in the prevention hierarchy of IDUs.

Figure 1.

Multilevel HIV prevention hierarchy, past and present. *SEP denotes syringe exchange programs.

NON–INJECTING DRUG USERS (NIDUs)

HIV risk and prevalence as well as transmission rates vary widely among NIDUs using crack, cocaine, methamphetamine, alcohol, and pills as well as noninjected heroin, but may be relatively high because of the co-occurrence of drug use with sexual risk behaviors (eg, unprotected sex, multiple partners, and survival sex) and the overlapping of social network risk groups.19–22 These associations have been dramatic, especially among men who have sex with men (MSM).23–26

Approaches to Screening and Prevention

Targeted interventions with outreach specialized to reach types of NIDUs according to drug of choice may be necessary given different behavioral patterns of drug use. However, in general, NIDU interventions should be comprehensive in their ability to serve multiple risk groups (eg, drug users, MSM) with multiple risk factors (eg, drug use, sex, mental health).27 For example, multicomponent interventions such as MP3 (Methods for Prevention Package Programs) and Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral and Treatment (SBIRT)28 need to include approaches along with wraparound services to be comprehensive in addressing drug users’ multiple, complex needs (eg, relating to sex, mental health, homelessness, and infectious and chronic disease).29 Current efforts in the United States are focused on reaching and engaging minority men who have sex with men (MSM), who have particularly high rates of HIV infection.30,31 In this population as in others, interventions need to go beyond “test and treat” (TNT) to assess and address drug use issues, including polydrug use.32 In a broader sense, incarceration and neighborhood factors that have been shown to influence availability and opportunity for drug use also need to be considered in addressing drug-related concerns.15,33

WHERE ARE WE NOW?

Especially with the advent of antiretroviral therapies, the spectrum of HIV prevention in drug users has broadened to include TNT; nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP); and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). These interventions need to be tailored to ensure that they are accessible and feasible for drug users and incorporated on multiple levels (eg, individual, community, and structural).

Test and Treat

TNT aims to reach virtually everyone in the US population and treat HIV infection with antiretroviral medications, an intervention that would presumably reduce population viral loads and HIV incidence.34 For NIDUs and IDUs alike, the success of TNT requires the ability to reach this more elusive population at higher risk of HIV exposure and to retain them in a program of frequent testing and treatment. TNT could be expanded outside conventional hospital, clinic, and emergency room settings to include those who attend drug treatment and IDUs who have developed rapport with syringe exchange programs and pharmacies. However, among hard-to-reach groups where HIV is making inroads, the purported benefits of TNT may be suboptimal without explicit strategies to incorporate HIV testing into a broad range of facilities on a widespread basis; to reach drug users who do not access services and are likely at highest risk of HIV exposure; to train health care workers to communicate effectively with and engage this population; to optimize approaches to maintain adherence to antiretroviral treatment, especially for those outside drug-abuse treatment; and to ensure that all those at risk for HIV exposure have access to all needed services.

nPEP and PrEP for IDUs

Elsewhere in this issue, nPEP and PrEP in general have been discussed. Data are sparse on nPEP for drug users in general and for IDUs in particular,35,36 and results of PrEP trials in IDUs are not yet available.37 Should the data show effectiveness, the next challenge will be to appropriately disseminate information via street outreach strategies. Although some view nPEP and PrEP for IDUs and NIDUs with trepidation because of valid concerns over drug toxicities, drug users’ ability to adhere to treatment, and the potential for development, within individuals, of drug resistance that would subsequently limit potential treatment options,38 it is feasible to integrate provision of these drugs into drug treatment programs and pharmacies, where there is the ability to frequently perform HIV testing and linkage to providers to monitor patients. Additional infrastructure is needed to attract and engage both IDUs and NIDUs.

Substance Abuse Treatment

Substance abuse treatment has been a mainstay for HIV prevention among drug users. For opiate abuse and dependence, methadone and now buprenorphine/naloxone are established treatments,12 which have the advantage of unchallenged integration into primary HIV care.39 The greater challenge has been the ability to produce effective substance abuse treatment for stimulant abuse. Several pharmacotherapies have been tested, and others are in the pipeline. For treatment of methamphetamine abuse, little or no benefit has been seen in trials for bupropion40 and modafinil,41 but efforts continue, with newer agents such as varenicline under investigation.42 The experience to date with pharmacologic treatment for cocaine and crack is similarly disappointing; the promise of antidepressants43 and carbamazepine44 has not been realized, but examination of newer drugs is ongoing.45 With the slower progress on pharmacologic treatments for methamphetamines and other stimulants, the most promising approach to date has been cognitive behavioral therapy with contingency management.46,47 As has been shown for IDUs, treatment combinations on multiple levels (eg, individual pharmacotherapy and behavioral change) are needed not only to reduce drug use but also to successfully target and maintain integration of NIDUs into social services.21,48

Alcohol, the most widely used drug, is also associated with sexual risk for HIV infection. Rapid screening tools for alcohol abuse and dependence have been developed, yet only half of HIV-infected problem drinkers discuss their predicament with their HIV care providers.49 Given the association of problem drinking with increased risk of HIV transmission and acquisition, , screening for alcohol use needs to be more widely incorporated into HIV care and research. A number of pharmacologic treatment options for alcohol misuse are being studied, including naltrexone50 and disulfiram.51 Yet no standard pharmacologic therapies for alcohol abuse and dependence exist. Techniques of Motivational Interviewing (MI) could possibly be effectively provided in primary HIV care settings.52,53 But MI’s effectiveness has been demonstrated only as a multisession intervention,, limiting its feasibility in many primary HIV care settings, where staff face many competing demands. This suggests that modifications are needed in the structure of MI content and its requirement for health care provider involvement ‥ Telephone counseling alone (or possibly as an adjunct to MI) has shown some promise for problem drinkers.54

Contingency management and conditional cash transfer are two iterations of another approach to substance abuse treatment and HIV prevention that has been used for some time.55 There is resistance to the idea of “rewarding” drug users, but available data from prospective studies suggest that this approach improves otherwise costly follow-up without increasing drug use.56

CONCLUSIONS: FROM STIGMATA TO REDEMPTION—MAKING EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS POSSIBLE

Multilevel, multicomponent interventions among IDUs have been successful at reducing HIV incidence and provide a model for more broadly addressing HIV prevention. Yet challenges remain—not only for IDUs but for the much larger population of noninjectors. Drug use needs to be approached comprehensively to reach and provide options for those who do not or cannot quit drugs. Further, going beyond specific programs into the policy choices that create resources to ensure access to services and support for adherence to the evidence-informed, health supporting protocols are currently available is warranted. Practical strategies to overcome problems of access and adherence include utilizing our standard tools of 1) education, to increase knowledge about behaviors that can prevent HIV infection at the individual and community levels; 2) HIV testing in nontraditional settings (eg, pharmacies) to reach drug users whose activities put them at high risk of HIV exposure; 3) behavioral interventions that not only address drug use–associated behaviors and health problems but also HIV risk behaviors, to lure and integrate drug users who are members of other overlapping risk groups; 4) drug treatment, which should be expanded, especially in communities where access is now poor and in primary HIV care settings; and, for IDUs, 5) syringe access, to increase access to sterile equipment. It is a combination of these strategies applied simultaneously on individual, community, and policy levels that have been successful in reducing HIV incidence and prevalence among drug users to date, and it is these strategies that researchers, community members, and policy makers should work to expand for use and application of upcoming HIV interventions.

Acknowledgments

Support: National Institute on Drug Abuse DA022144, DA022123, DA04334, and DA019964 (all, Crawford and Vlahov)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Accessed August 18, 2010]. Available at: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k7nsduh/2k7results.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.HIV diagnoses among injection-drug users in states with HIV surveillance—25 states, 1994–2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:634–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman SR, Lieb S, Tempalski B, et al. HIV among injection drug users in large US metropolitan areas, 1998. J Urban Health. 2005;82:434–445. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metzger DS, Navaline H. HIV prevention among injection drug users: the need for integrated models. J Urban Health. 2003;80 suppl 3:iii59–iii66. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Public Health Service. [Accessed August 20, 2010];HIV Prevention Bulletin: Medical Advice to Persons Who Inject Illicit Drugs. 1997 May 9; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/idu/pubs/hiv_prev.htm.

- 6.Des Jarlais DC, Marmor M, Friedmann P, et al. HIV incidence among injection drug users in New York City, 1992–1997: evidence for a declining epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:352–359. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson KE, Vlahov D, Solomon L, et al. Temporal trends of incident human immunodeficiency virus infection in a cohort of injecting drug users in Baltimore, Md. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1305–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vlahov D, Fuller CM, Ompad DC, et al. Updating the infection risk reduction hierarchy: preventing transition into injection. J Urban Health. 2004;81:14–19. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372:669–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copenhaver MM, Johnson BT, Lee IC, et al. Behavioral HIV risk reduction among people who inject drugs: meta-analytic evidence of efficacy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.04.002. PMCID: PMC2452992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorensen JL, Masson CL, Perlman DC. HIV/hepatitis prevention in drug abuse treatment programs: guidance from research. [Accessed August 19, 2010];Sci Pract Perspect. 2002 1:4–11. doi: 10.1151/spp02114. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/PDF/perspectives/vol1no1/02Perspectives-HIVHep.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan LE, Metzger DS, Fudala PJ, et al. Decreasing international HIV transmission: the role of expanding access to opioid agonist therapies for injection drug users. Addiction. 2005;100:150–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heimer R. Syringe exchange programs: lowering the transmission of syringe-borne diseases and beyond. Public Health Rep. 1998;113 suppl 1:67–74. PMCID: PMC1307728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Des Jarlais DC, Perlis T, Arasteh K, et al. HIV incidence among injection drug users in New York City, 1990 to 2002: use of serologic test algorithm to assess expansion of HIV prevention services. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1439–1444. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.036517. PMCID: PMC1449378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuller CM, Galea S, Caceres W, et al. Multilevel community-based intervention to increase access to sterile syringes among injection drug users through pharmacy sales in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:117–124. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069591. PMCID: PMC1716247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santibanez SS, Garfein RS, Swartzendruber A, et al. Update and overview of practical epidemiologic aspects of HIV/AIDS among injection drug users in the United States. J Urban Health. 2006;83:86–100. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9009-2. PMCID: PMC2258331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moss AR, Vranizan K, Gorter R, et al. HIV seroconversion in intravenous drug users in San Francisco, 1985–1990. AIDS. 1994;8:223–231. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199402000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta SH, Galai N, Astemborski J, et al. HIV incidence among injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland (1988–2004) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:368–372. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243050.27580.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celentano DD, Latimore AD, Mehta SH. Variations in sexual risks in drug users: emerging themes in a behavioral context. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:212–218. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0030-4. PMCID: PMC2801160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell MM, Latimer WW. Unprotected casual sex and perceived risk of contracting HIV among drug users in Baltimore, Maryland: evaluating the influence of non-injection versus injection drug user status. AIDS Care. 2009;21:221–230. doi: 10.1080/09540120801982897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strathdee SA, Sherman SG. The role of sexual transmission of HIV infection among injection and non-injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2003;80 suppl 3:iii7–iii14. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methamphetamine use and HIV risk behaviors among heterosexual men—preliminary results from five northern California counties, December 2001–November 2003. [Accessed August 20, 2010];MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006 55:273–277. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5510a2.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colfax G, Coates TJ, Husnik MJ, et al. Longitudinal patterns of methamphetamine, popper (amyl nitrite), and cocaine use and high-risk sexual behavior among a cohort of San Francisco men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2005;82 Suppl 1:i62–i70. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Fontaine YM, et al. Walking the line: stimulant use during sex and HIV risk behavior among Black urban MSM. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostrow DG, Plankey MW, Cox C, et al. Specific sex drug combinations contribute to the majority of recent HIV seroconversions among MSM in the MACS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:349–355. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Bland S, et al. Problematic alcohol use and HIV risk among Black men who have sex with men in Massachusetts. AIDS Care. 2010;22:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09540120903311482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meade CS, Sikkema KJ. HIV risk behavior among adults with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:433–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babor TF, McRee BG, Kassebaum PA, Grimaldi PL, Ahmed K, Bray J. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Subst Abus. 2007;28:7–30. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, Stegbauer T, Stein JB, Clark HW. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:280–295. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorbach PM, Murphy R, Weiss RE, et al. Bridging sexual boundaries: men who have sex with men and women in a street-based sample in Los Angeles. J Urban Health. 2009;86 suppl 1:63–76. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9370-7. PMCID: PMC2705489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tobin KE, Latkin CA. An examination of social network characteristics of men who have sex with men who use drugs. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:420–424. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Cranston K, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and partner characteristics of black MSM in Massachusetts at increased risk for HIV infection and transmission. J Urban Health. 2009;86:602–623. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9363-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedman SR, Cooper HL, Osborne AH. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1002–1008. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA. 2009;301:2380–2382. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Almeda J, Allepuz A, Simon BG, et al. Non-occupational post-exposure HIV prophylaxis. Knowledge and practices among physicians and groups with risk behavior [in Spanish] Med Clin (Barc) 2003;121:321–326. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(03)73937-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vlahov D, Robertson AM, Strathdee SA. Prevention of HIV infection among injection drug users in resource-limited settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50 suppl 3:S114–S121. doi: 10.1086/651482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed August 20, 2010];Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention; planning for potential implementation in the U.S. [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site]. Updated August 21 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prep/resources/factsheets/implementation.htm#Planning.

- 38.Grant RM. Antiretroviral agents used by HIV-uninfected persons for prevention: pre- and postexposure prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50 suppl 3:S96–S101. doi: 10.1086/651479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan LE, Bruce RD, Haltiwanger D, et al. Initial strategies for integrating buprenorphine into HIV care settings in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43 suppl 4:S191–S196. doi: 10.1086/508183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shoptaw S, Heinzerling KG, Rotheram-Fuller E, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of bupropion for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heinzerling KG, Swanson AN, Kim S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;109:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zorick T, Sevak RJ, Miotto K, et al. Pilot safety evaluation of varenicline for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. [Accessed August 20, 2010];J Exp Pharmacol. 2010 2:13–18. Available at: http://www.dovepress.com/pilot-safety-evaluation-of-varenicline-for-the-treatment-of-methamphet-peer-reviewed-article-JEP. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lima MS, Reisser AA, Soares BG, Farrell M. Antidepressants for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD002950. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lima AR, Lima MS, Soares BG, Farrell M. Carbamazepine for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD002023. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preti A. New developments in the pharmacotherapy of cocaine abuse. Addict Biol. 2007;12:133–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee NK, Rawson RA. A systematic review of cognitive and behavioural therapies for methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:309–317. doi: 10.1080/09595230801919494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shoptaw S, Reback CJ, Larkins S, et al. Outcomes using two tailored behavioral treatments for substance abuse in urban gay and bisexual men. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Degenhardt L, Mathers B, Vickerman P, et al. Prevention of HIV infection for people who inject drugs: why individual, structural, and combination approaches are needed. Lancet. 2010;376:285–301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Metsch LR, Pereyra M, Colfax G, et al. HIV-positive patients' discussion of alcohol use with their HIV primary care providers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ray LA, Chin PF, Miotto K. Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism: clinical findings, mechanisms of action, and pharmacogenetics. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9(1):13–22. doi: 10.2174/187152710790966704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barth KS, Malcolm RJ. Disulfiram: an old therapeutic with new applications. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9:5–12. doi: 10.2174/187152710790966678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65 doi: 10.1002/jclp.20638. 12321245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown RL, Saunders LA, Bobula JA, Mundt MP, Koch PE. Randomized-controlled trial of a telephone and mail intervention for alcohol use disorders: three-month drinking outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1372–1379. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haug NA, Sorensen JL. Contingency management interventions for HIV-related behaviors. [Accessed August 20, 2010];Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2006 3:154–159. doi: 10.1007/s11904-006-0010-5. Available at: http://www.springerlink.com/content/q677577l2q007157/fulltext.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Festinger DS, Marlowe DB, Croft JR, et al. Do research payments precipitate drug use or coerce participation? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]