Abstract

Diabetic retinopathy can lead to progressive loss of vision and is a leading cause of blindness. The Ins2Akita/+ mouse model of diabetes develops significant retinal and systemic pathology, but how these affect visual behavior is unknown. Here, we show that Ins2Akita mice have progressive, quantifiable vision deficits in an optomotor behavior. This mouse line is a promising model in which to understand the contribution of retinal neuronal injury during the chronic hyperglycemia and hypoinsulinemia of diabetes to deficits in vision.

Keywords: diabetes, diabetic retinopathy, optokinetic response, Ins2Akita mouse, vision, retina

Diabetes is a leading cause of blindness in working age adults [1]. Before complete loss of vision, progressive deficits occur in grating acuity and contrast sensitivity in discrimination tasks in patients with Type I and Type II diabetes mellitus and diabetic retinopathy [2-5]. Diabetics have also been shown to have disturbances in optokinetic behaviors [6, 7]. To what degree behavioral visual deficits occur in animal models of diabetes has not been established. A main goal of treatments for diabetic retinopathy is to prevent loss of visual function, but common measures of diabetic injury to the visual system in animal models have relied on retinal histopathology, such as neuronal and vascular cell loss, and not function.

The most widely used measure of functional performance deficits in the visual pathway in studies of diabetic animals has been the electroretinogram (ERG). The ERG has been used in animal models primarily to quantify overall retinal responses to full-field flashes of light and has been very valuable in the understanding of photoreceptor dysfunction in aging and disease [8-10]. Although ON bipolar cell responses are known to dominate the b-wave of the ERG, contributions of other inner retinal neurons to components of the ERG waveform are less well understood. Yet inner retinal circuits and the amacrine and ganglion neurons which comprise them are significantly affected by diabetes [2, 11]. For example, animal models show deficits in the oscillatory potentials and STR, both of which are thought to arise in the inner retina [12], but it is unknown how these changes directly relate to an animal’s vision. Furthermore, anesthetics routinely used to record ERGs can acutely increase blood glucose, and blood glucose levels are known to affect ERG wave amplitudes [13]. Chronic low blood sugar leads to visual deficits in mice [14], and acute hyperglycemia may increase human retinal sensitivity [15]. These considerations confound interpretation of the ERG in diabetic models. Thus, comprehensive tests of visual function in animal models of diabetes are needed.

The Akita mutation of the Insulin2 gene causes loss of the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas due to ER stress and a severe decrease in insulin production and release by the remaining cells [16-18]. Mice heterozygous for the Akita allele of the Insulin2 gene lose pancreatic beta cell mass because of this defect in insulin production and become chronically hyperglycemic at about 1 month of age [16, 19]. This mouse model has been shown to develop many hallmarks of diabetic retinopathy including morphological alteration of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), loss of inner retinal neurons, loss of pericytes, capillary dropout, and increased vascular permeability [20-22]. Here, we show that the Ins2Akita mouse model of diabetes has progressive, quantifiable vision deficits in spatial frequency threshold and contrast sensitivity of a subcortically driven, behavioral vision task.

Heterozygous Ins2Akita male mice on a C57Bl6 background (“Akita”) and C57Bl6J wild-type females were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and mated in our animal facility to generate the mice used here. Only male mice were used as a diabetes model because male mice heterozygous for the Akita allele consistently develop hypoinsulinemia and hyperglycemia at about 4 weeks of age [19, 20]. All procedures were approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center Animal Care and Use Committee and followed guidelines set forth in the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Visual Research.

Blood glucose was measured using test strips read with a meter (AlphaTrak; Abbott Labs; Abbott Park, IL) at 5 to 11 weeks of age, and glucose levels were (mean ± sem mg/dL) 420 ± 13.5 for heterozygous Akita mice and 175 ± 6.4 for their normoglycemic, wild-type littermates. Glucose levels that reached the maximum of the meter were considered to be 600 mg/dL. We confirmed the presence or absence of the Akita allele in all of the mice tested here (genotyping by Transnetyx, Inc.; Cordova, TN). The genotyping results were used to classify the mice. All of the mice that were confirmed to have the Akita allele by genotyping had blood glucose levels of 300 mg/dL or higher, except for three that were between 265 and 285 mg/dL at testing. Hyperglycemia is generally considered to be present at blood glucose levels >250 mg/dL [23]. Male Akita mice have previously been shown, by weekly blood glucose testing in several separate studies, to remain consistently hyperglycemic through at least 31 weeks of age [17, 18, 20, 24, 25]. The blood glucose levels of a sample of 42 of the mice used here were tested at later time points (19 control and 23 Akita), and all values matched expectations based on the genotyping results (data not shown).

Spatial frequency threshold and contrast sensitivity of a specific optomotor behavior were assessed for awake, freely moving mice. Optomotor responses to horizontally drifting, vertically oriented gratings were observed and scored using the OptoMotry system (Cerebral Mechanics, Inc.; Lethbridge, Canada). For testing, a mouse was placed on a platform in the center of a chamber with walls made of computer monitors. Sinusoidal gratings were projected on all four monitors as a cylinder centered on the head, and the virtual cylinder displayed on the monitors was rotated at 12 deg/sec in both horizontal directions. The mouse was imaged via an overhead video camera for a trained observer to score smooth head turns in response to the rotating gratings. We observed these tracking responses as being robust at middle spatial frequencies and contrasts and diminishing until they were extinguished at threshold, similar to what has been described previously [26].

Mice were tested at 28 to 31 weeks of age (“7.5 months old” group; n = 17 littermate control mice, n = 13 Akita mice), at 18 to 23 weeks of age (“5 months old” group; n = 14 littermate control mice, n = 17 Akita mice), and at 8 to 11 weeks of age (“2.5 months old” group; n = 15 littermate control mice, n = 17 Akita mice). Animals with one or both eyes having obvious damage at testing—including damage from corneal infection or micro-ophthalmia (which is known to occur at a low rate in the C57Bl6 background) or from which individual measurements could not be made—were entirely excluded.

The spatial frequency of gratings displayed at maximum contrast was varied using a stair-step protocol with a minimum step size of 0.003 cyc/deg until the highest frequency still eliciting a response was determined for each direction. This 100% cutoff value was reported by the software when the observer indicated that the given spatial frequency elicited a response no fewer than four times; the software allowed for the observer to indicate no tracking at the same spatial frequency up to three times (Cerebral Mechanics, Inc.). To measure contrast sensitivity, the contrast was varied in stair-step fashion with a minimum step size of 0.1% at a fixed spatial frequency. After spatial frequency threshold determination, the contrast threshold at 0.064 cyc/deg was measured followed by the contrast threshold at 0.103 cyc/deg. These values encompass the spatial frequency that gives the peak sensitivity in C57Bl6 mice [26]. Contrast sensitivity was calculated as the reciprocal of the contrast threshold. Because the stimulus was always shown to the animal’s full visual field, both eyes were illuminated, including the binocular zones. Thus, we averaged the values for the two eyes for each measurement for each mouse. A single trained observer blind to the blood glucose status of the mice indicated whether or not a smooth head-turn tracking response in the direction of drift occurred for each grating presentation. Directions were randomly interleaved. For all groups, the average time taken to make each measurement, including both directions, ranged from 7.5 to 10.5 min, and none of these times were significantly different from each other (data not shown). Contrast was calculated as (max−min)/(max+min), where max and min are the maximum and minimum luminance values of the gratings, measured using a photometer (S471; UDT Instruments, Inc.). Because of non-zero minimum luminance of LCD screens, maximum contrast is below the theoretical maximum of 100%; the actual maximum contrast was 98.6%. Groups were compared using two-way ANOVA, with health status and age group as factors, followed by Tukey HSD post-hoc tests (R software package) [27]. Correlation of different measures was tested on a per-animal basis by determining a t statistic for correlation coefficients with a null hypothesis of no correlation (IgorPro; WaveMetrics; Lake Oswego, OR). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

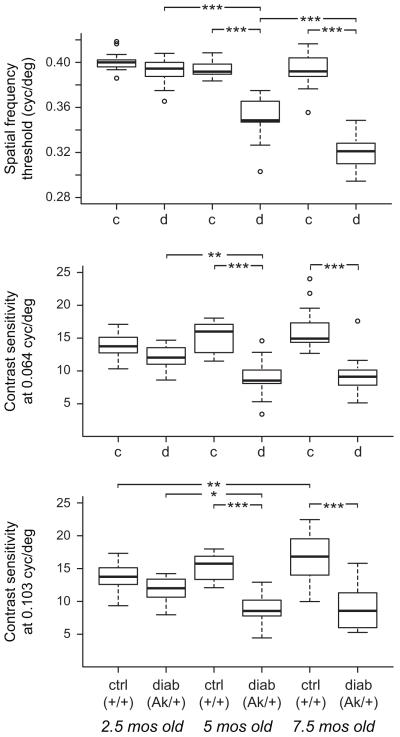

We find that diabetic Ins2Akita mice have significant visual deficits at 5 months and 7.5 months of age but not at 2.5 months of age. These deficits are in the spatial frequency threshold at maximum contrast and contrast sensitivity at both 0.064 and 0.103 cyc/deg of the optomotor head-turning reflex response to vertical, sinusoidal gratings drifting horizontally across the visual field (Table 1; Figure 1). Spatial frequency threshold progressively declined across the three age groups, while contrast sensitivity at either spatial frequency did not decline further from 5 to 7.5 months. We found no significant deficit in the young mice, unlike similar data presented in abstract form finding spatial frequency threshold deficits in this task at about 2 months of age [28; also see 29]. In our data, comparison using a Student’s t-test indicated the young control and diabetic mice significantly differed for all three measures, but the more stringent Tukey’s HSD tests after ANOVA we needed to use to allow for additional comparisons of the ages did not indicate significant differences. Thus, our data in young mice shows only a non-significant trend for lower spatial frequency threshold and poorer contrast sensitivity in these mice. These findings suggest that deterioration in visual performance may occur soon thereafter in Akita mice in our conditions.

Table 1.

| Group | Spatial frequency threshold (cpd) |

Contrast sensitivity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age (mos) |

geno- type |

n (mice) |

max. contrast | 0.064 cpd | 0.103 cpd | |||

| mean | sem | mean | sem | mean | sem | |||

| 2.5 | +/+ | 15 | 0.401 | 0.002 | 13.8 | 0.5 | 13.8 | 0.6 |

| Akita/+ | 17 | 0.393 | 0.003 | 12.1 | 0.4 | 11.8 | 0.4 | |

| 5 | +/+ | 14 | 0.394 | 0.002 | 15.3 | 0.6 | 15.2 | 0.5 |

| Akita/+ | 17 | 0.351 | 0.004 | 9.0 | 0.7 | 8.9 | 0.5 | |

| 7.5 | +/+ | 17 | 0.393 | 0.003 | 16.1 | 0.7 | 17.0 | 0.9 |

| Akita/+ | 13 | 0.320 | 0.004 | 9.5 | 0.8 | 9.1 | 0.9 | |

Figure 1.

Ins2Akita mice have significant deficits in spatial frequency threshold and contrast sensitivity in an optomotor task at 5 and 7.5 months of age but not at 2.5 months of age. Diabetic male mice heterozygous for the Akita allele (“diab” or “d”) were compared to control littermate mice (“ctrl” or “c”) for head tracking responses to horizontally drifting vertical sinusoidal gratings. The spatial frequency threshold of the behavior was determined as the maximum spatial frequency at maximum contrast that still induced smooth head tracking movements (top panel). Note that the axis begins at 0.28 cyc/deg. The minimum contrast that still induced these movements—i.e., the contrast threshold, the reciprocal of which is the contrast sensitivity—was also determined at 0.064 cyc/deg (middle panel) and 0.103 cyc/deg (lower panel). Boxes, bounded by the first and third quartiles, also show the median (black line). Box plot whiskers are drawn to 1.5 times interquartile distance. Outliers are shown as open circles. By all three measures, Ins2Akita mice diabetic for at least 4 months were deficient (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001).

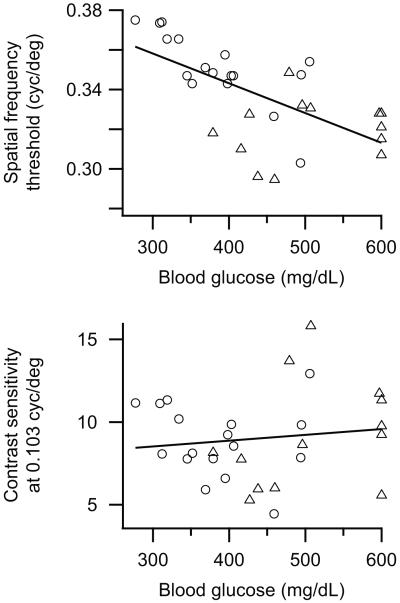

To determine whether the deficits in visual function might depend on the severity of the diabetic phenotype, we examined correlations between the visual behavior measurements and the blood glucose levels (which were measured at 8 weeks of age on average) for the combined data from the 5 and 7.5 months old age groups of Akita animals. Spatial frequency threshold was significantly correlated with blood glucose level (r = −0.63, p<0.001; Fig. 2, top panel). Contrast sensitivity was not correlated with blood glucose level, either at 0.064 cyc/deg (r = 0.15, p>0.10) or at 0.103 cyc/deg (r = 0.13, p>0.10; Fig. 2, bottom panel). When the ages were considered separately, only the spatial frequency threshold values for the 5 month old group was significantly correlated to blood glucose level (data not shown).

Figure 2.

The combined spatial frequency thresholds (top panel) of 5 month old (open circles) and 7.5 month old (open triangles) Ins2Akita mice were correlated to blood glucose levels while contrast sensitivities at 0.103 cyc/deg (bottom panel) were not. Linear fits to the data are also shown (black lines). Contrast sensitivity data at 0.064 cyc/deg was essentially identical and is not shown. The average age of the mice at blood glucose determination was 8 weeks.

To examine the relationship among the measurements, we determined correlations between spatial frequency threshold and contrast sensitivity at each spatial frequency (Table 2). For all age groups, the contrast sensitivities at 0.064 cyc/deg were significantly correlated with those at 0.103 cyc/deg At 2.5 months of age, only the diabetic animals had significant correlations between spatial frequency threshold and either contrast sensitivity measurement. This correlation broke down at 5 and 7.5 months, except for sensitivity at 0.103 cyc/deg. The control animals only showed significant correlations at 5 months of age. While we did not collect data for contrast sensitivity at additional spatial frequencies, these findings, along with the difference in age-related progression of decline in these performance measures, suggests that diabetes may be causing changes to the shape of the contrast sensitivity to spatial frequency relation.

Table 2.

| Group | Spatial freq. threshold vs. Contrast sens., 0.064 cpd |

Spatial freq. threshold vs. Contrast sens., 0.103 cpd |

Contrast sens., 0.064 cpd vs. Contrast sens., 0.103 cpd |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age (mos) |

geno- type |

r | p | r | p | r | p | |||

| 2.5 | +/+ | −0.07 | > 0.10 | n.s. | −0.10 | > 0.10 | n.s. | 0.95 | <0.0001 | *** |

| Akita/+ | 0.54 | 0.027 | * | 0.65 | 0.005 | ** | 0.95 | <0.0001 | *** | |

| 5 | +/+ | 0.67 | 0.009 | ** | 0.68 | 0.007 | ** | 0.96 | <0.0001 | *** |

| Akita/+ | 0.36 | > 0.10 | n.s. | 0.49 | 0.047 | * | 0.91 | <0.0001 | *** | |

| 7.5 | +/+ | 0.46 | 0.061 | n.s. | 0.17 | > 0.10 | n.s. | 0.65 | 0.005 | ** |

| Akita/+ | 0.13 | > 0.10 | n.s. | 0.50 | 0.079 | n.s. | 0.66 | 0.014 | * | |

The youngest group of tested control animals had slightly but significantly lower contrast sensitivity at 0.103 cyc/deg than the 7.5 month old group, and a non-significant trend with increasing age for slightly better, not worse, contrast performance can be seen (Fig. 1). Decreased activity of older mice during testing may have made it subjectively easier to detect small and slow head-turning motions near threshold because of the longer period that the animals remained still while attending to the visual stimuli. Older animals tended to be less active in the testing apparatus, and were apparently able to maintain relatively long periods of visual attention, evident as longer periods of continuous tracking. Younger animals tended to break visual attention and interrupt tracking episodes with body movements. Although we did not measure gain of the head-turning response, we also observed that diabetic animals more often had poorer, less robust tracking motions in general. Nonetheless, the deficits in spatial frequency threshold clearly became progressively worse with age in the diabetic animals, despite this perceived decrease in activity and increase in visual attention episodes on the testing platform.

The behavioral task used here allows assessment of specific visual functions. These measures could be a useful part of a model system for determining efficacy of treatments for diabetic retinopathy and for understanding whether and how pathology of the retina caused by diabetes leads to visual performance deficits, which is currently unknown. The optomotor response does not depend on the visual cortex [30]; rather, optokinetic movements are thought to be guided by direction-selective retinal input to the subcortical nuclei of the accessory optic system (AOS) by the same system that drives optokinetic eye-tracking movements [26, 31-33]. Direction-selective RGCs that respond to movement of edges brighter than background (ON DSGCs) project to these nuclei, but it is still not known whether the ON DSGCs sensitive to motion in the temporal-nasal direction in the visual field provide the visual input necessary and sufficient for the visual behavior. It is also unknown whether these neurons, the function of their target neurons in the brain, or the function of targets farther downstream in the circuit are affected by diabetes. Thus, a major unanswered question is the cellular origin of these deficits.

The Akita mouse develops significant retinal pathology, which suggests these vision deficits could arise due to neuronal injury in the retina. Expression levels of several retinal synaptic proteins are lower than in normoglycemic animals, suggesting impaired synaptic function due to hyperglycemia or to lack of insulin production [34]. The number of cells undergoing apoptosis, including neurons, is also increased [20]. RGCs are decreased in number (by about 20%), and many of the remaining RGCs have aberrant morphology, including enlarged somas, swollen primary dendrites, and dendritic blebbing [20, 21]. The RGCs most affected in this way are ON RGCs with medium to large somas. Based on our visual behavior results, we hypothesize that some of these RGCs are ON DSGCs that drive the optomotor behavior. However, the physiology of RGCs in animal models of diabetes is nearly completely unknown [11]. Directionality in DSGCs is established by inputs to the ganglion cells from the cholinergic amacrine cell network [35]. The number of cholinergic amacrines is decreased following three months of diabetes in mice with the Akita allele, which could thus affect responses that depend on motion detection [22].Because these larger RGCs were most affected while the morphology of other RGCs appeared normal [21], it is possible that smaller RGCS are more likely to be spared from damage in the Ins2Akita mouse model of diabetes. Additional visual tests might reveal such differences using visually guided behaviors that require intact visual cortex with innervation from other RGC populations [36]. For example, if maximum visual acuity is determined by small RGCs with small dendritic fields, such as the local edge detectors (LEDs) [37], maximum behavioral acuity may be spared while subcortical, optomotor acuity is not, as in the deficits revealed here.

Recent data in abstract form suggests that the retinal dopaminergic system is critical for normal performance in the optomotor task used here [38]. Specific retinal loss of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting enzyme for dopamine production, or injection of dopamine receptor antagonists into the eyes of mice led to decreased behavioral performance in the optomotor task. Because Akita retinas have been shown to have a decreased number of dopaminergic amacrines after 6 months of diabetes [22], it is possible that the apparently general loss of retinal neurons in diabetes impacts this behavior specifically through decreased dopaminergic signaling in the retina.

It is also possible that the defect leading to the visual deficits lies completely or partially outside of the retina in the visual system or in the systems that integrate and direct the motor output. For example, diabetes causes neuropathy that impacts some autonomic ganglia but not others [39]. Peripheral neuropathy in Akita mice leads to decreases in both sciatic motor and also tail sensory motor nerve conduction velocities and also leads to increased latency to paw withdrawal from a noxious heat stimulus at both 2 and 5 months of age [24; but see 40]. This neuropathy was accompanied by disturbances in gait in Akita mice, suggesting impaired motor output. Thus, a neuropathy may exist that could impact transmission of the motor output necessary for the optomotor behavior or from the retina to the AOS. On the other hand, the same mice showed no cognitive impairment in the Morris water maze test of learning and memory and had similar latencies to find and swim to a visually cued platform in the Morris water tank, indicating cognitive and physical abilities similar to control mice. The origin of the visual performance deficits in Akita diabetic mice and their relationship to the pathological complications of diabetes are still open and intriguing questions. The combination of retinal pathology and quantifiable measures of specific visual functions in the Ins2Akita mouse suggests it will be a valuable model for determining how much of the progressive visual deficits are due to impaired retinal function resulting from retinal pathology in diabetic retinopathy.

Highlights.

-

>

We find Ins2Akita diabetic mice have visual performance deficits.

-

>

The optokinetic tracking response to drifting gratings was measured.

-

>

Spatial frequency threshold and contrast sensitivity declined during diabetes.

-

>

Spatial frequency threshold deficits were correlated to blood glucose levels.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a UTHSCSA Research Committee New Faculty Award and pilot project awards from the Nathan Shock Institute and the UTHSCSA Institute for the Integration of Medicine and Science CTSA federal grant (UL1RR025767) to RCR.

Abbreviations

- cyc/deg

cycles per degree

- ERG

electroretinogram

- mos

months

- RGC

retinal ganglion cell

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Fong DS, Aiello L, Gardner TW, King GL, Blankenship G, Cavallerano JD, et al. Retinopathy in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S84–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jackson GR, Barber AJ. Visual dysfunction associated with diabetic retinopathy. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10:380–4. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bangstad HJ, Brinchmann-Hansen O, Hultgren S, Dahl-Jorgensen K, Hanssen KF. Impaired contrast sensitivity in adolescents and young type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients with microalbuminuria. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1994;72:668–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1994.tb04677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Parravano M, Oddone F, Mineo D, Centofanti M, Borboni P, Lauro R, et al. The role of Humphrey Matrix testing in the early diagnosis of retinopathy in type 1 diabetes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1656–60. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.143057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gardner TW, Abcouwer SF, Barber AJ, Jackson GR. An integrated approach to diabetic retinopathy research. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;129:230–5. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Darlington CL, Erasmus J, Nicholson M, King J, Smith PF. Comparison of visual--vestibular interaction in insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Neuroreport. 2000;11:487–90. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002280-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nicholson M, King J, Smith PF, Darlington CL. Vestibulo-ocular, optokinetic and postural function in diabetes mellitus. Neuroreport. 2002;13:153–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200201210-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Weymouth AE, Vingrys AJ. Rodent electroretinography: methods for extraction and interpretation of rod and cone responses. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008;27:1–44. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kolesnikov AV, Fan J, Crouch RK, Kefalov VJ. Age-related deterioration of rod vision in mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11222–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4239-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vollrath D, Feng W, Duncan JL, Yasumura D, D’Cruz PM, Chappelow A, et al. Correction of the retinal dystrophy phenotype of the RCS rat by viral gene transfer of Mertk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12584–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221364198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kern TS, Barber AJ. Retinal ganglion cells in diabetes. J Physiol. 2008;586:4401–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bui BV, Fortune B. Ganglion cell contributions to the rat full-field electroretinogram. J Physiol. 2004;555:153–73. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Brown ET, Umino Y, Loi T, Solessio E, Barlow R. Anesthesia can cause sustained hyperglycemia in C57/BL6J mice. Vis Neurosci. 2005;22:615–8. doi: 10.1017/S0952523805225105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Umino Y, Everhart D, Solessio E, Cusato K, Pan JC, Nguyen TH, et al. Hypoglycemia leads to age-related loss of vision. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19541–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604478104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Barlow RB, Khan A, Farell B. Metabolic modulation of human visual sensitivity ARVO Annual Meeting; Fort Lauderdale, FL. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang J, Takeuchi T, Tanaka S, Kubo SK, Kayo T, Lu D, et al. A mutation in the insulin 2 gene induces diabetes with severe pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in the Mody mouse. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:27–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Oyadomari S, Koizumi A, Takeda K, Gotoh T, Akira S, Araki E, et al. Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:525–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI14550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Imai J, Katagiri H, Yamada T, Ishigaki Y, Suzuki T, Kudo H, et al. Regulation of pancreatic beta cell mass by neuronal signals from the liver. Science. 2008;322:1250–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1163971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yoshioka M, Kayo T, Ikeda T, Koizumi A. A novel locus, Mody4, distal to D7Mit189 on chromosome 7 determines early-onset NIDDM in nonobese C57BL/6 (Akita) mutant mice. Diabetes. 1997;46:887–94. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Barber AJ, Antonetti DA, Kern TS, Reiter CE, Soans RS, Krady JK, et al. The Ins2Akita mouse as a model of early retinal complications in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2210–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gastinger MJ, Kunselman AR, Conboy EE, Bronson SK, Barber AJ. Dendrite remodeling and other abnormalities in the retinal ganglion cells of Ins2 Akita diabetic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2635–42. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gastinger MJ, Singh RS, Barber AJ. Loss of cholinergic and dopaminergic amacrine cells in streptozotocin-diabetic rat and Ins2Akita-diabetic mouse retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3143–50. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Clee SM, Attie AD. The genetic landscape of type 2 diabetes in mice. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:48–83. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].de Preux Charles AS, Verdier V, Zenker J, Peter B, Medard JJ, Kuntzer T, et al. Global transcriptional programs in peripheral nerve endoneurium and DRG are resistant to the onset of type 1 diabetic neuropathy in Ins2 mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Choeiri C, Hewitt K, Durkin J, Simard CJ, Renaud JM, Messier C. Longitudinal evaluation of memory performance and peripheral neuropathy in the Ins2C96Y Akita mice. Behav Brain Res. 2005;157:31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Prusky GT, Alam NM, Beekman S, Douglas RM. Rapid quantification of adult and developing mouse spatial vision using a virtual optomotor system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4611–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].R Development Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Barber AJ, Schuller K, Bridi MA, Bronson SK. Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity are reduced in the Ins2Akita diabetic mouse; ARVO Annual Meeting; Fort Lauderdale, FL. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kern TS, Tang J, Berkowitz BA. Validation of structural and functional lesions of diabetic retinopathy in mice. Mol Vis. 2010;16:2121–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Douglas RM, Alam NM, Silver BD, McGill TJ, Tschetter WW, Prusky GT. Independent visual threshold measurements in the two eyes of freely moving rats and mice using a virtual-reality optokinetic system. Vis Neurosci. 2005;22:677–84. doi: 10.1017/S0952523805225166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tabata H, Shimizu N, Wada Y, Miura K, Kawano K. Initiation of the optokinetic response (OKR) in mice. J Vis. 2010;10:131–7. doi: 10.1167/10.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Simpson JI. The accessory optic system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:13–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Yoshida K, Watanabe D, Ishikane H, Tachibana M, Pastan I, Nakanishi S. A key role of starburst amacrine cells in originating retinal directional selectivity and optokinetic eye movement. Neuron. 2001;30:771–80. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Vanguilder HD, Brucklacher RM, Patel K, Ellis RW, Freeman WM, Barber AJ. Diabetes downregulates presynaptic proteins and reduces basal synapsin I phosphorylation in rat retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Demb JB. Cellular mechanisms for direction selectivity in the retina. Neuron. 2007;55:179–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Prusky GT, West PW, Douglas RM. Behavioral assessment of visual acuity in mice and rats. Vision Res. 2000;40:2201–9. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].van Wyk M, Taylor WR, Vaney DI. Local edge detectors: a substrate for fine spatial vision at low temporal frequencies in rabbit retina. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13250–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1991-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Iuvone PM, Abey J, Aseem F, Ghai K, Boatright JH, MacMahon DG, et al. Visual Function in Mice with Conditional, Retina-specific Disruption of the Tyrosine Hydroxylase Gene: Differential Roles of Dopamine D1 and D4 Receptors; ARVO Annual Meeting; Fort Lauderdale, FL. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Schmidt RE, Green KG, Snipes LL, Feng D. Neuritic dystrophy and neuronopathy in Akita (Ins2(Akita)) diabetic mouse sympathetic ganglia. Exp Neurol. 2009;216:207–18. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kakoki M, Sullivan KA, Backus C, Hayes JM, Oh SS, Hua K, et al. Lack of both bradykinin B1 and B2 receptors enhances nephropathy, neuropathy, and bone mineral loss in Akita diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10190–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005144107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]