Abstract

We consider integrative modeling of multiple gene networks and diverse genomic data, including protein-DNA binding, gene expression and DNA sequence data, to accurately identify the regulatory target genes of a transcription factor (TF). Rather than treating all the genes equally and independently a priori in existing joint modeling approaches, we incorporate the biological prior knowledge that neighboring genes on a gene network tend to be (or not to be) regulated together by a TF. A key contribution of our work is that, to maximize the use of all existing biological knowledge, we allow incorporation of multiple gene networks into joint modeling of genomic data by introducing a mixture model based on the use of multiple Markov random fields (MRFs). Another important contribution of our work is to allow different genomic data to be correlated and to examine the validity and effect of the independence assumption as adopted in existing methods. Due to a fully Bayesian approach, inference about model parameters can be carried out based on MCMC samples. Application to an E. coli data set, together with simulation studies, demonstrates the utility and statistical efficiency gains with the proposed joint model.

Keywords: Bayesian hierarchical model, Markov random field, Gene networks, Joint modeling, Mixture models, Systems biology

1 Introduction

In this paper we consider integrative modeling of multiple sources of genomic data and gene networks to accurately identify the regulatory target genes of a transcription factor (TF). TFs, a class of regulatory proteins, play a central role in controlling gene expression: a TF stimulates or inhibits its target gene’s transcription into messenger RNA (mRNA) by binding to some specific DNA subsequences in the gene’s promoter region. In our motivating example, we are interested in identifying the target genes of LexA in E. coli. LexA is an important TF involved in DNA repair and cell division: it is a repressor for genes involved in the “SOS” response whose transcription is induced in response to DNA damage due to ultraviolet (UV) or chemical exposures (Zhang et al. 2010). Under normal growth conditions, LexA binds to the promoter regions of these “SOS” genes, repressing their transcription. When DNA becomes extensively damaged, the LexA repressor is cleaved and loses its function. As a result, the expression of “SOS” genes is induced, and DNA repair ability in the cells is enhanced. Recently, LexA was shown to be essential in the acquisition of bacterial mutations which lead to resistance to some antibiotic drugs (Cirz et al. 2005). Therefore, a thorough understanding of LexA regulation is not only crucial to the elucidation of the DNA repair mechanism in E. coli, a common model microorganism, but also beneficial to antibiotic drug development (Butala et al. 2009).

The task of identifying the target genes of a TF can be approached by using ChIP-chip data (also called DNA-protein binding data or genome-wide location analysis), which provide evidence about genome-wide physical binding sites of a specific TF in living cells. However, those DNA-TF interactions may not be functional in terms of regulating gene expression because other conditions such as binding of co-regulators and recruitment of RNA polymerase II complex are also needed to initiate the target gene’s transcription. Two other types of genomic data, also available for LexA, provide complementary information about TF-gene regulation: microarray gene expression data comparing expression changes before and after knocking-out or mutating a TF-coding gene, and DNA sequence data which are aligned and scanned to find specific binding sites of a TF, called consensus sequence or motif. Although extremely valuable, these two data sources provide only partial information: for expression data, genes that are directly or indirectly regulated by the TF will all show changes in expression levels, while DNA sequence data provide only potential binding sites which may or may not eventually be bound by the TF. Because each data source measures different aspects of TF-gene regulation, and high-throughput data are inherently associated with high noise levels, using one type of data alone may result in high false positives or false negatives.

In contrast, it is now widely recognized that an integrative analysis of multiple types of genomic data should be more efficient in identifying the target genes of a TF (see Wang et al. 2005; Jensen et al. 2007; Pan et al. 2008; Xie et al. 2010, and references therein). There are two main classes of joint modeling approaches in the literature: regression methods and mixture model methods. First, in a regression framework, one type of data (e.g., ChIP-chip binding data or DNA sequence data) is regressed on another type of data (e.g., gene expression data; Colon et al. 2003; Sun et al. 2006; Wei and Pan 2008b). In particular, Jensen et al. (2007) proposed a Bayesian regression model in a variable selection framework to combine all three sources of data to construct gene regulatory networks (i.e., a set of multiple TFs and their regulatory target genes). Note that regression-based methods require a large number of replicated expression arrays, which are not applicable to the LexA data to be analyzed here. Second, in a mixture model framework, inference is based on the posterior probability of being a target given gene-specific measurements of different sources of data. Wang et al. (2005) proposed a parametric mixture model for both DNA sequence data and expression/binding data; Pan et al. (2008) extended the mixture model of Wang et al. to one that is able to integrate all three data sources to detect the targets of a TF. Conditional independence is commonly assumed in a mixture joint model, i.e., different sources of data are independent given that a gene is or is not a target, which may or may not hold in practice. In particular, it has been reported in the experimental biology literature that the binding strength of LexA to its target genes depends on the extent to which the binding site matches the canonical motif of LexA (Michel 2005; Butala et al. 2009). Hence, the conditional independence assumption seems incorrect, at least for the binding and sequence data, motivating us here to extend the parametric mixture model of Pan et al. to allow conditional dependence. We propose to summarize each data source with a scalar summary statistic for each gene, and thus, the three sources of genomic data can be conveniently modeled by a trivariate normal mixture model. Moreover, by adopting a fully Bayesian approach, we are able to make inference about the conditional correlation structures for all three data sources based on Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) samples.

In addition to relaxing the conditional independence assumption, another key contribution of our proposed method here is to allow incorporation of multiple gene networks into joint modeling of diverse types of genomic data to detect the targets of a TF. Gene networks represented by undirected graphs with genes as nodes and gene-gene interactions as edges provide a powerful means to concisely summarize biological knowledge that is accumulated over thousands of experiments. An emerging class of statistical methods is to incorporate gene network information into analysis of genomic data (Wei and Li 2007, 2008; Li and Li 2008; Wei and Pan 2008a, 2010). In particular, Wei and Li (2007) proposed a discrete Markov random field (MRF)-based mixture model to incorporate gene network information into statistical analysis of gene expression data to boost the power for detection of differentially expressed genes. Wei and Pan (2010) proposed a Bayesian implementation of the MRF-based mixture model of Wei and Li (2007), and compared it with the Gaussian MRF-based mixture model of Wei and Pan (2008a). The network-based methods are motivated by the biological fact that neighboring genes on a network, e.g., co-expression or functional coupling gene network, are more likely to be co-regulated by a TF than non-neighboring ones.

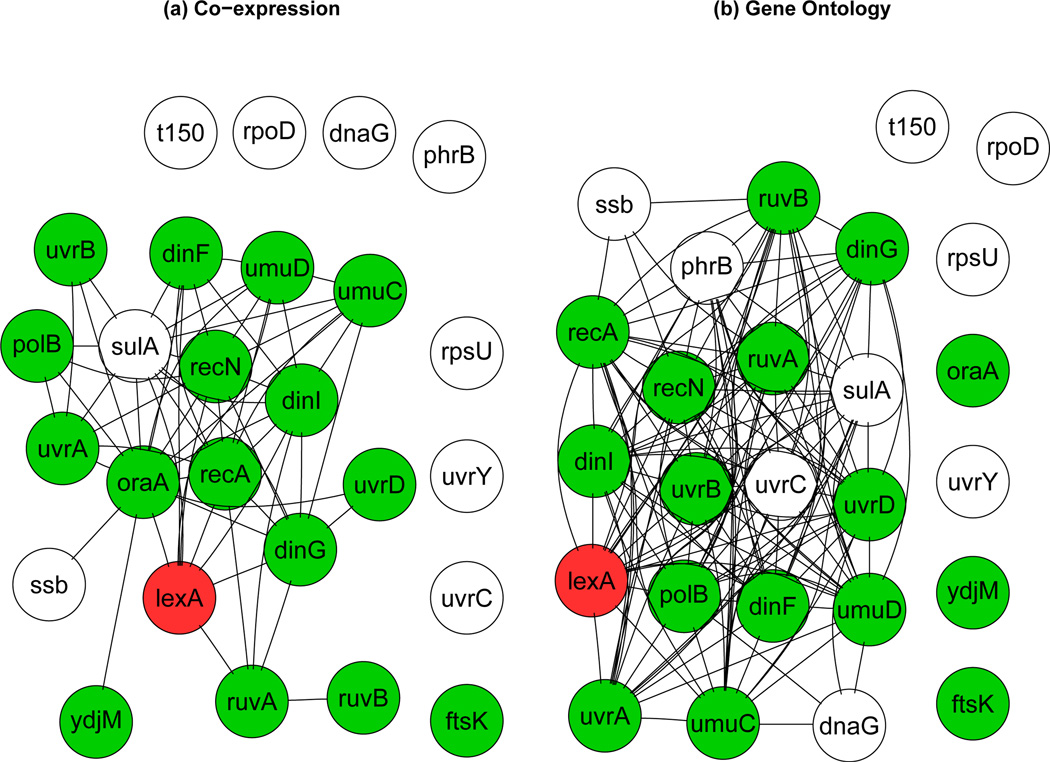

One limitation of existing network-based methods, including the aforementioned ones, is that only a single gene network is allowed to be integrated with a single type of genomic data. However, as biological knowledge accumulates rapidly, multiple gene networks become available. For humans, existing gene networks include the KEGG gene regulatory network (Kanehisa and Goto 2002), the functional gene network of Franke et al. (2006), and several protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, for example, the Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD) of Keshava Prasad et al. (2008) and the Online Predicted Human Interaction Database (OPHID) of Brown et al. (2005), among others. Interactions between two genes in different networks may have different biological implications. For example, for E. coli two gene networks can be used to analyze the LexA data: (1) a co-expression network constructed based on a compendium of gene expression microarrays, where two genes are direct neighbors if their expression levels were highly correlated across about 400 experimental conditions; (2) a functional coupling network induced by a Gene Ontology (GO; Ashburner et al. 2000) semantic similarity, where two genes are direct neighbors if their functional annotations are specific and close enough in the GO, a database containing the most comprehensive existing knowledge of gene function. Figure 1 shows subnetworks, one from each of the aforementioned networks, consisting of LexA’s known and putative target genes as available from RegulonDB (Gama-Castro et al. 2008), a database containing all known TF-gene regulatory interactions in E. coli. As we can see, a gene may have different sets of direct neighbors according to different networks. This is in part because edges in different networks reflect different perspectives of gene-gene interactions, e.g., co-expression or co-function, and in part because of incomplete or simply wrong annotation shown by a network. Since the two gene networks contain partial yet complementary information about gene-gene interactions, integrating both of them with ChIP-chip binding, gene expression and DNA sequence data is expected to boost the power for detecting the target genes of LexA. As a key contribution, here we propose a mixture model to address this problem based on the use of multiple MRFs. Statistical inference is carried out in a fully Bayesian framework. The proposed method can be easily extended to integrate more gene networks and more types of genomic data, providing a general statistical framework for integrative analysis of genomic data.

Figure 1.

Subnetworks, one from each of the following two networks, consisting of LexA’s known (colored/shaded nodes) and putative (blank nodes) target genes as available from RegulonDB. The two gene networks are: (a) co-expression network and (b) GO- induced functional coupling network.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. We first describe the LexA data including ChIP-chip binding, gene expression, DNA sequence data and two gene networks for E. coli. Next, we introduce a multivariate normal mixture model for joint modeling of multiple sources of genomic data only, followed by a unified mixture model for integrating multiple gene networks and genomic data based on the use of multiple MRFs. We discuss statistical inference for the proposed models in a fully Bayesian framework. Parameter estimates are based on MCMC samples. We apply the new methods to the LexA data to identify its regulatory target genes. We evaluate the proposed methods’ predictive performance by comparing the results with the known and putative targets listed in RegulonDB (v6.4). We also show results from simulation studies to investigate the conditional independence assumption as well as the effects of integrating multiple networks and diverse types of genomic data. We end with a discussion of some existing issues and possible future work.

2 The Data

2.1 ChIP-chip binding, gene expression and DNA sequence data

The ChIP-chip binding data, gene expression data and DNA sequence data were extracted and processed from three sources as reported in Wade et al. (2005), Courcelle et al. (2001) and RegulonDB (v4.0), respectively.

The ChIP-chip data included two LexA samples (called LexA1 and LexA2 respectively) and two control samples (one Gal4 and one MelR (no Ab, no antibody) samples) hybridized on four Affymetrix Antisense Genome Arrays respectively. First, the arrays were background corrected with the MAS 5 algorithm, followed by quantile normalization. Second, four log2 intensity ratios (LIRs) were calculated, corresponding to the four combinations of any two arrays, for each probe: LexA1/Gal4, LexA1/no Ab, LexA2/Gal4, LexA2/no Ab; a large LIR indicated a locus containing enriched LexA, i.e, a binding site of LexA. Third, for each of the four array combinations, the LIRs were smoothed over all probes with a sliding window of 1250 base pairs (bp) along the chromosome. Finally, gene i’s binding score Bi, a summary statistic measuring the relative abundance of the TF binding to the gene, was taken to be the average of its four LIR peaks from its coding region, or if there were probes from its intergenic region, Bi was the larger of i) the average of its four LIR peaks from its coding region and ii) that from its intergenic region.

The expression data were drawn from four cDNA microarrays profiling gene expression levels for the wild type before and 20 minutes after UV treatment, and for the LexA mutant before and 20 minutes after UV treatment; a common control sample was used for each array. Two-channel intensities on each array were normalized using the loess local smoother to eliminate dye bias, as implemented in the R package sma (Yang et al. 2002). Suppose that normalized log-ratios of the two-channel intensities for gene i on the four arrays were M1i,…,M4i respectively, then the summary statistic for gene expression data was taken as Ei = (M2i − M1i) − (M4i − M3i). Because LexA is known to be a repressor of some “SOS” response genes, it is expected that the regulatory targets of LexA should have larger values of Ei’s (i.e., expression changes).

The DNA sequence data were obtained as following. Ten known binding sites of LexA were downloaded from RegulonDB (v4.0), involving nine genes each with one binding site and gene LexA with two binding sites. These ten binding sites were input into MEME (Bailey and Elkan 1995) to find a top consensus sequence (motif). scanACE (Roth et al. 1998) was then used to scan the whole genome with a very low threshold such that at least one subsequence matching the motif could be obtained for most genes; the maximum of all the matching scores for gene i was taken as Si, the summary statistic for the sequence data.

After combining the three data sources and deleting genes with any missing values, we obtained G = 3779 genes in the combined data. Table 1 shows a small portion (5 of 3779 genes) of the resulting data set.

Table 1.

Some data from the LexA data set.

| Index | Binding (Bi) | Expression (Ei) | Sequence (Si) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GENE1 | −0.490 | 0.076 | 15.573 |

| GENE2 | 2.275 | 2.777 | 23.968 |

| GENE3 | 0.619 | 1.377 | 24.164 |

| GENE4 | 0.210 | −0.208 | 15.464 |

| GENE5 | 0.120 | −0.346 | 13.055 |

2.2 Gene networks for E. coli

Two gene networks were constructed for E. coli as mentioned before: a co-expression network and a functional coupling network.

The co-expression gene network was derived from 380 microarray experiments across a variety of conditions, available at the Many Microbe Microarrays Database (M3D; Faith et al. 2008). Two genes were direct neighbors if the Pearson correlation coefficient of their expression profiles across the 380 experiments was greater than 0.65, resulting in a network with 3,208 nodes (genes) and 86,791 edges (interactions). The cutoff 0.65 was chosen so that the resulting network was neither too dense, including many false positive interactions, nor too sparse, failing to include many true positive interactions. As a comparison, a cutoff of 0.6 would lead to 147,563 interactions, while a cutoff of 0.7 would result in 46,666 interactions. We also performed sensitivity analysis to investigate how robust the network-based analysis results are to different cutoffs for the co-expression network (see Section 4.3 for details).

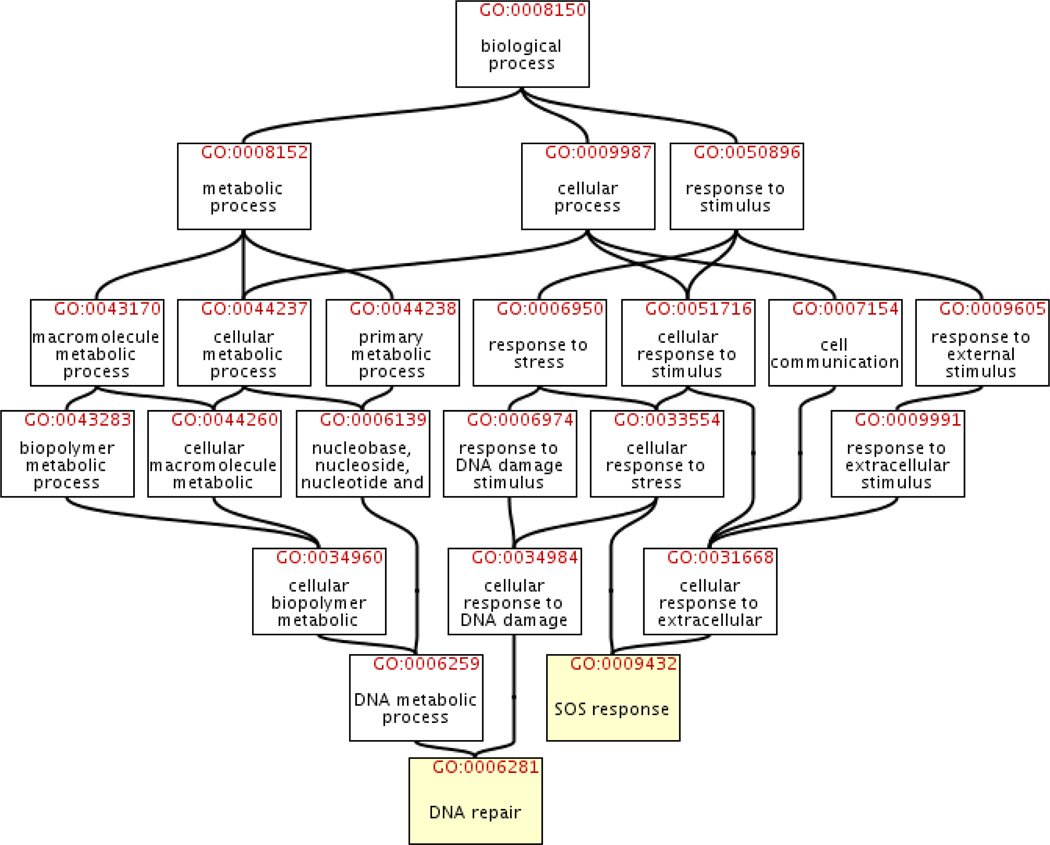

The functional coupling gene network was induced from the Gene Ontology (GO), a compendium of existing knowledge, derived from various sources, about gene function. GO is structured as a directed acyclic graph (DAG): each node corresponds to a GO category; a parent node represents a more general biological function, whereas its child node is a subclass or a part of it; any gene in a child node is necessarily in its parent node. For example, GO category GO:0033554 with annotation “cellular response to stress” has a child node GO:0009432 with a more specific annotation “SOS response.” The GO similarity between two genes is defined as the maximum number of common nodes in all paths back to the root node of the ontology (“biological process”) from all nodes to which those genes are assigned (see Wu et al. 2005 for more details). If the GO similarity between two genes is large, then at a very specific level the two genes are involved in at least one common biological process. Figure 2 illustrates a DAG induced from the GO. We computed the GO similarity for each pair of genes. Two genes were direct neighbors on the induced functional coupling network if their GO similarity was no less than five, which means there were at least five common nodes in their shared longest path back to the root node “biological process” from all nodes in which they are annotated. Figure 2 shows an example of how to calculate the GO similarity between two genes. The induced network has 1,644 nodes and 116,422 edges.

Figure 2.

The combined directed acyclic graph (DAG) of DAGs induced from the GO terms “DNA repair” (GO:0006281) and “SOS response” (GO:0009432). lexA and dinG, two known target genes of TF LexA, are annotated in both terms. Because there are 6 and 5 nodes in the longest paths from “DNA repair” and “SOS response” to the root node “biological process”, respectively (the root node itself is not counted), the GO similarity between lexA and dinG is 6. The graph was adapted from QuickGO GO Browser (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/QuickGO/).

Some summary statistics and sample subnetworks of the two gene networks can be found in Table 2 and Figure 1, respectively. The networks differ substantially in the density of edges due to different definitions of gene-gene interactions.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of the two gene networks used in the analysis.

| Network | # of nodes | # of edges | percentiles of # of direct neighbors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 100% | |||

| co-expression | 3,208 | 86,791 | 1 | 5 | 20 | 64 | 424 |

| functional coupling (GO) | 1,644 | 116,422 | 1 | 48 | 102 | 249 | 708 |

3 Statistical Methods

3.1 Notation

Our goal is to identify regulatory target genes of a given TF based on given ChIP-chip binding, gene expression and DNA sequence data. We assume that the three data sources have been summarized as (Bi, Ei, Si) for each gene i, for i = 1, …, G, as described in Section 2.1. Depending on the latent (unobserved) state of gene i, i.e., whether it is a target or not, we have Ti = 1 or Ti = 0, respectively. Denote the distribution functions of (Bi, Ei, Si) for Ti = 1 and Ti = 0 as f1 and f0, respectively.

3.2 Standard Mixture Joint Model

We first consider joint modeling of binding, expression and sequence data without incorporating gene networks. We have the following standard mixture joint model (SMJM):

| (1) |

where π1 = Pr(Ti = 1) is the prior probability of gene i being a target. Note that it is the same for all the genes. We further specify the conditional distribution fj = ϕ(.; μj, Σj), a multivariate normal density function with mean vector μj and covariance matrix Σj for j = 0, 1. Here we allow the conditional covariance matrix Σj to have a general structure, i.e., the three data sources can be correlated given Ti. A special case is diagonal covariance matrix , i.e., the three data sources are conditionally independent, as assumed in Pan et al. (2008). When only one type of data, e.g., gene expression data, is considered, the conditional distributions f0 and f1 become univariate normal density functions, and we call the corresponding model “standard mixture model” (SMM).

3.3 MRF-based Mixture Joint Model

Because neighboring genes on a network, e.g., co-expression or functional coupling network, tend to be co-regulated by a TF and there is more than one gene network available, each containing complementary yet partial information about gene-gene interactions, it is desired to incorporate multiple gene networks into joint modeling of genomic data. Here we propose an MRF-based Mixture Joint Model (MRF-MJM) to accomplish this goal. In contrast to assuming a priori iid gene state Tis as in the SMJM, we model the state vector T = (T1, …, TG)′ as MRFs defined on multiple neighborhood systems, each corresponding to a gene network. Specifically, we propose the following auto-logistic model for the distribution of Ti, conditional on T(−i) = {Tl; l ≠ i},

| (2) |

where Φ = (γ, β1, …, βK), γ ∈ ℝ, βk ≥ 0, ∂i(k) is the set of indices for gene i’s direct neighbors on network 𝒢k for is the number of gene i’s neighbors having state j on network 𝒢k for j = 0, 1, and thus is the corresponding total number of neighbors. The conditional probability of gene i being a target only depends on the states of its neighbors, as defined on the K networks, which is often referred to as the “local dependency” property. Note that we assume the contribution of each network to logitPr(Ti = 1|T(−i), Φ) is additive, weighted by the non-negative parameters βks. Larger βk would induce more similar states (target or nontarget) among neighboring genes on network 𝒢k. In addition, the conditional distribution of the observed data (Bi, Ei, Si) given Ti is the same as that in the SMJM.

The advantage of our proposed model is to combine all available gene network information, and thus to boost the statistical power for detecting target genes as much as possible. For example, as shown is Figure 1, oraA is a true target that is not connected to any other target genes in the GO-induced network, but is connected to other targets in the co-expression network. As a result, in contrast to using the GO-induced network alone, oraA’s prior probability of being a target can still be boosted by using the proposed model here to combine both networks. Moreover, because is always between −1 and 1, βks are comparable and may be used to measure how informative network 𝒢k is. When β1 = … = βK = 0, the MRF-MJM is reduced to the SMJM. This can be seen by noticing that logitPr(Ti = 1|T(−i), Φ) = γ = logitPr(Ti = 1) = logit(π1), or equivalently, , where π1 is the prior probability of being a target as defined in (1) in the SMJM.

Singleton genes, i.e., those without any neighbors in a network, are allowed in the proposed MRF-MJM here. Denote 𝒮k as the set of indices for singletons in gene network 𝒢k. For singleton gene i ∈ 𝒮k, we set . If , then logitPr(Ti = 1|T(−i), Φ) = logitPr(Ti = 1) = γ.

Due to the unknown normalizing constant C(Φ) in the joint distribution of T = (T1, …, TG)′, the likelihood l(T; Φ) does not have a closed form. Instead, we propose to use the pseudolikelihood of Besag (1986):

| (3) |

The maximizer of the pseudolikelihood was shown to be a consistent estimator of the MRF parameters Φ (Winkler 2006, page 272), while Ryden and Titterington (1998) showed that the pseudolikehood pl(T; Φ) provides a good approximation to the genuine likelihood l(T; Φ) in Bayesian hierarchical modeling as adopted here. We found the approximation works well in our real data analysis and simulation study.

Note that our proposed MRF defined on multiple neighborhoods is similar to that used by Deng et al. (2004) in the context of protein function prediction, rather than detection of the target genes of a TF here.

3.4 Prior distributions

We use vague or noninformative prior distributions. We denote by MV N(μ, Σ) the multivariate normal distribution with mean vector μ and covariance matrix Σ, and denote by W((ρR)−1, ρ) the Wishart distribution with mean vector R−1. Reparameterize the component-wise mean vector as: μ1 = μ0 + θ. We use the following priors for the parameters in the conditional distribution of the observed data: μ0 ~ MV N(0, C), θ ~ MV N(0, C)I(θ > 0), where C = diag(106, 106, 106); for j = 0, 1, where R is taken as the estimated marginal covariance matrix of the three data sources whose off-diagonal elements are close to zero. Since we have , R is approximately the expected prior variance of Σj. This is considered as a very vague prior with respect to the correlation parameters (Carlin and Louis 2008, page 338). For the SMJM, we have π1 ~ Beta(1, 1). For the MRF-MJM, we have γ ∝ 1 and βk ∝ I(0 ≤ βk < 6), k = 1, …, K.

3.5 Statistical inference

We carry out statistical inference in a fully Bayesian framework via MCMC sampling. The MCMC algorithm for the SMJM can be implemented in WinBUGS V1.40 (Spiegelhalter et al. 2003), while we wrote an R program to implement the MCMC algorithm for the MRF-MJM. The WinBUGS code for the SMJM is provided in the supplemental materials. The MCMC algorithm for the MRF-MJM can be found in the Appendix, and the R program is available upon request.

We run three parallel chains of our MCMC algorithms starting from different values, each run for 10,000 iterations after discarding the first 5,000 as burn-in samples. We use the three parallel chains to monitor convergence and obtain more stable posterior estimates by combining the three chains. We use trace plots and the R̂ statistic of Gelman and Rubin (1992) to monitor the mixing of the Markov chains; see Section 4.3 and Supplemental Figure 2. The posterior mean of any parameter based on combining 10,000 MCMC samples after 5,000 burn-ins from each of the three chains is used as its point estimate. In particular, we rank genes based on the posterior probability of being a target . False Discovery Rate (FDR) can be estimated based on p̂i as discussed by Wei and Pan (2010), which is not pursued in this study.

4 Application to LexA data

4.1 Conditional independence assumption

We applied the SMJM to jointly model the ChIP-chip binding, gene expression and DNA sequence data. Table 3 shows the point and interval estimates for the parameters in the conditional correlation matrices of the three data sources. For the nontarget component, the three sources of data appeared to be independent with each other. Interestingly, for the target component, binding and sequence data were highly correlated, in contrast to the other two pairs: binding and expression data, sequence and expression data, which turned out to be only slightly correlated and independent, respectively. This is consistent with the recent finding that LexA’s binding affinity to its regulatory targets depends on the extent to which the binding site matches the consensus sequence for LexA (Butala et al. 2009). In addition, our results suggest that LexA is quite efficient in repressing its target genes’ expression: weak binding only decreases its repression effect slightly.

Table 3.

Posterior estimates for component-wise (conditional) correlation matrices of binding (B), expression(E), and sequence(S) data in the SMJM. Numbers in the parentheses are 95% credible intervals.

| non-target component | target component | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | E | S | B | E | S | ||

| B | 1 | 0.013 (−0.027, 0.047) | −0.013 (−0.053,0.023) | B | 1 | 0.119 (0.034,0.184) | 0.475 (0.427,0.513) |

| E | 1 | 0.010 (−0.029,0.045) | E | 1 | 0.077 (−0.016, 0.147) | ||

| S | 1 | S | 1 | ||||

4.2 Predictive performance

We evaluated the different methods’ predictive performance by comparing the ranks given by each method for 26 LexA’s known and putative targets annotated in RegulonDB (v6.4), as shown in Table 4. Note that known target genes of LexA were those experimentally verified via binding of purified proteins, which was considered as “strong” evidence by RegulonDB (Gama-Castro et al. 2008), whereas putative target genes were those supported only by some “weak” evidence, e.g., gene expression analysis or computational prediction based on similarity to consensus sequence. Thus, evaluations based on known targets are much more reliable than those based on putative ones. As a result, we first focused on LexA’s known targets.

Table 4.

Ranks given by various methods based on posterior probabilities for known (marked by *) and putative target genes of LexA annotated in RegulonDB. “SMM”:standard mixture model; “S”:SMJM with diagonal covariance; “S.mul”:SMJM with general covariance; “co-exp”:co-expression network; “GO”:functional coupling network induced by GO.

| Targets | Expression | Binding SMM |

Sequence SMM |

Binding+Expression+Sequence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMM | MRF-MJM | S | S.mul | MRF-MJM | |||||||

| co-exp | GO | co-exp+GO | co-exp | GO | co-exp+GO | ||||||

| umuD* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| recN* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| recA* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| lexA* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| dinI* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 48 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ydjM* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 70 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| oraA* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 82 | 1206 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| polB* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 156 | 153 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| umuC* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 192 | 3500 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| sulA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ssb | 129 | 1 | 133 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ruvA* | 146 | 1 | 133 | 1 | 127 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| uvrA* | 163 | 134 | 159 | 133 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| uvrB* | 172 | 134 | 175 | 133 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| t150 | 172 | 176 | 167 | 169 | 2118 | 50 | 173 | 215 | 178 | 172 | 174 |

| dinF* | 216 | 182 | 214 | 178 | 2471 | 1 | 1 | 145 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| uvrD* | 245 | 259 | 249 | 261 | 262 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ruvB* | 311 | 226 | 313 | 231 | 2118 | 1456 | 644 | 576 | 367 | 614 | 373 |

| dinG* | 450 | 311 | 439 | 314 | 96 | 136 | 168 | 168 | 142 | 166 | 144 |

| rpsU | 1190 | 1810 | 2694 | 2445 | 470 | 1091 | 886 | 955 | 1021 | 1105 | 1266 |

| phrB | 1738 | 2858 | 2819 | 3137 | 1334 | 531 | 1460 | 1686 | 2031 | 1898 | 2154 |

| uvrC | 2534 | 1401 | 2715 | 1467 | 3022 | 3334 | 3080 | 2980 | 1937 | 2978 | 1956 |

| dnaG | 3060 | 3119 | 3100 | 3266 | 2471 | 781 | 2831 | 3169 | 2897 | 2978 | 3087 |

| rpoD | 3336 | 3727 | 2422 | 2969 | 2471 | 791 | 2622 | 3169 | 2897 | 2199 | 2685 |

| ftsK* | 3723 | 3583 | 2313 | 2727 | 75 | 128 | 169 | 171 | 180 | 166 | 174 |

| uvrY | 3723 | 3472 | 2313 | 2727 | 3022 | 3500 | 3080 | 2964 | 3173 | 2789 | 2884 |

| # tied rank 1 | 128 | 133 | 132 | 132 | 53 | 36 | 145 | 144 | 141 | 145 | 143 |

In general, incorporating gene networks and combining additional types of genomic data increased the chance of detecting the true targets as compared to using a single type of genomic data alone; this was evidenced by higher, in some cases substantially higher, ranks based on the integrative analyses than those based on using binding, expression, or sequence data alone. When network information was not utilized, many of LexA’s known targets did not have consistently high ranking based on any of the three genomic data sources alone. For example, oraA and dinF were ranked 82nd and 2471st, respectively, based on binding data alone, while they were ranked 1206th and tied first, respectively, based on sequence data alone. In contrast, the majority of LexA’s known targets (14 out of 17) were boosted to a highest rank, i.e., tied at the first with posterior probability equal to 1, by combining all three sources of genomic data. On the other hand, incorporating multiple gene networks into modeling of a single source of genomic data also led to dramatic rank improvement. For example, ruvA and uvrB were ranked 146th and 172nd based on expression data alone, but with the incorporation of gene networks their ranks improved to a tied first and 133rd, respectively. This was achieved without the aid of additional genomic data such as binding and sequence data, demonstrating the extra power gained by incorporating multiple gene networks. Compared with the significant rank improvement by the network-based analyses of a single type of genomic data, integrating multiple networks with all three sources of genomic data resulted in less dramatic improvement in predictive performance over joint modeling of genomic data only, possibly because the latter already had very high predictive power.

In addition, several features are noticeable. First, using a general conditional covariance structure in the SMJM did not lead to improved rankings as compared to using a diagonal conditional covariance structure. As a result, we used a diagonal conditional covariance structure in all MRF-based analyses for better predictive performance. Second, when integrating more than one gene network, we observed that the predictive performance tended to be compromised, i.e., the ranks based on both networks were often between those based on the co-expression network alone and those based on the GO-induced network alone. For example, dinG was ranked 142nd and 166th by the co-expression network-based and GO network-based MRF-MJM, respectively, whereas it was ranked 144th by the MRF-MJM that incorporated both networks. Third, as shown in Table 5, the relative magnitude of the weights βs for the two gene networks in the MRF-MJM were quite consistent: the co-expression network had higher weight than did the GO-induced network. Given the observation that the co-expression network-based analyses tended to lead to higher ranks than the GO network-based analyses, especially for modeling the gene expression alone, β may be used to measure how “good” a gene network is. One possible reason why the GO-induced gene network was not as good as the co-expression network was that the former network was much more densely connected, as illustrated by Table 2 and Figure 1, resulting in higher probability of target and nontarget genes being direct neighbors in the network, and thus, reduced power of the network-based methods.

Table 5.

Posterior means of parameters in the MRF-MJM (B: Binding; E: Expression; S: Sequence).

| Genomic data | Networks | γ | βco–expression | βGO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B+E+S | co-expression | −1.33 | 1.16 | - |

| GO | −1.72 | - | 0.84 | |

| co-expression + GO | −1.20 | 1.07 | 0.61 | |

| E | co-expression | −0.88 | 1.35 | - |

| GO | −1.30 | - | 0.99 | |

| co-expression + GO | −0.73 | 1.26 | 0.71 | |

Our joint modeling analyses also enabled us to potentially distinguish true targets of LexA from false positives in the putative target gene list. Among the nine putative targets, three genes - sulA, ssb and t150 - were consistently highly ranked by various models based on different data sources, and thus were very likely to be true targets of LexA. In contrast, the rest six putative targets had consistent low rankings, suggesting that they were likely to be false positive target genes. Interestingly, as shown in Figure 1, sulA and ssb were both direct neighbors of some known targets of LexA in both co-expression and GO gene networks, whereas none and only three of the six genes that were likely to be false positives were direct neighbors of known targets in the co-expression and GO network, respectively.

We noticed that there were quite a few genes with tied rank ones, ranging from 36 to 145 genes across different data sources and networks (Table 4). Those genes’ genomic data, i.e., binding, expression or sequence scores, were among the highest, and, as a result of their falling in the farthest right tail of the mixture distribution, the MCMC ended up with always drawing Ti = 1 for those genes across the entire finite iterations. It is noteworthy that the number of tied ones mainly depended on how much the two mixture components f0 and f1 in (1) were separated. Specifically, the expression data, whose two components had the best separation among the three data sources, led to 128 tied ones, whereas the sequence data, least separated, had 36 tied ones. Combining the three sources resulted in a higher number of tied ones than did any single source alone. Ties at other ranks were possible due to finite iterations of the MCMC.

4.3 Convergence diagnostics and sensitivity analysis

Given the large number of parameters, we only visually check the MCMC convergence for the mixture component and MRF parameters, i.e., μ0, μ1, Σ and Φ, whose convergence should also indicate that of the latent state vector T = (T1, …, TG)′. The trace plots did not reveal any convergence problems and the R̂ statistics of Gelman and Rubin (1992) were all close to 1, indicating that the multiple chains mixed with each other and converged by 5,000 iterations; see Supplemental Figure 2. The posterior probabilities p(Ti = 1) based on each individual Markov chain showed very little difference; nevertheless, we combined the MCMC samples from the three chains to obtain more stable posterior estimates.

In our proposed network-based joint model, we used noninformative or vague priors for the mixture component and MRF parameters as described in Section 3.4, whereas we used gene networks as informative priors for the latent state vector T. As evidence of minimal influence of the adopted priors on the posterior estimates of the mixture model parameters, the resulting posterior means in the SMJM were very close to the maximum likelihood estimates (MLEs) obtained via the EM algorithm (Dempster et al. 1977) (results not shown). On the other hand, we performed a sensitivity analysis to investigate how robust the network-based results were to potential incomplete/misspecified gene networks. Specifically, we applied the two co-expression networks with correlation coefficient cutoffs of 0.60 and 0.70 to the expression data alone as well as joint modeling of the three data sources, and compared the results to those based on the co-expression network with the cutoff of 0.65. Supplemental Figure 1 shows the three subnetworks, consisting of LexA’s known and putative target genes, from the co-expression networks with the cutoffs of 0.60, 0.65 and 0.70, respectively. The genes that formed a connected subnetwork were the same for the cutoffs 0.60 and 0.65, whereas ydjM and ssb became singletons in the subnetwork with the cutoff of 0.70. As shown in Supplemental Table 1, in spite of quantitative difference in the known target genes’ ranks based on the co-expression networks with different cutoffs, the network-based analyses consistently improved the predictive performance compared with the analyses of genomic data alone. As of the singleton genes ydjM and ssb in the co-expression subnetwork with the cutoff of 0.70, only ssb had slightly lower rank based on the network-based analysis of expression data and all other network-based analyses resulted in tied first for both genes due to strong genomic data signals. Our results demonstrate that the network-based methods are reasonably robust to misspecification of the network structures, consistent with previous sensitivity analysis results (Wei and Pan 2008a, 2010; Wei and Li 2008).

5 Simulation study

To further evaluate the conditional independence assumption and the effects of integrating multiple networks and diverse types of genomic data, we conducted a simulation study that mimicked the real data: the co-expression network was more informative than the GO-induced network and the conditional covariance matrices in the simulation model were based on those estimated from the real data. Specifically, the latent states vector T was based on the fitted MRF-MJM that incorporated both gene networks, while, given T, the observed genomic data were generated based on the fitted SMJM with a general conditional covariance structure. We let the top 487 genes, which are π̂1 = 13% of total 3779 genes, in the fitted MRF-MJM that incorporated both networks be targets (Ti = 1) and the rest of the 3292 genes as non-targets (Ti = 0). Note that the posterior means for the weight parameters βco–exp and βGO were 1.06 and 0.61, respectively. Given T, we simulated the binding, expression and sequence data from the fitted conditional normal distributions with nontarget mean vector μ̂0 = (0.11, 0.02, 13.35)′, target mean vector μ̂1 = (0.50, 0.26, 14.58)′ and covariance matrices corresponding to the correlation matrices in Table 3.

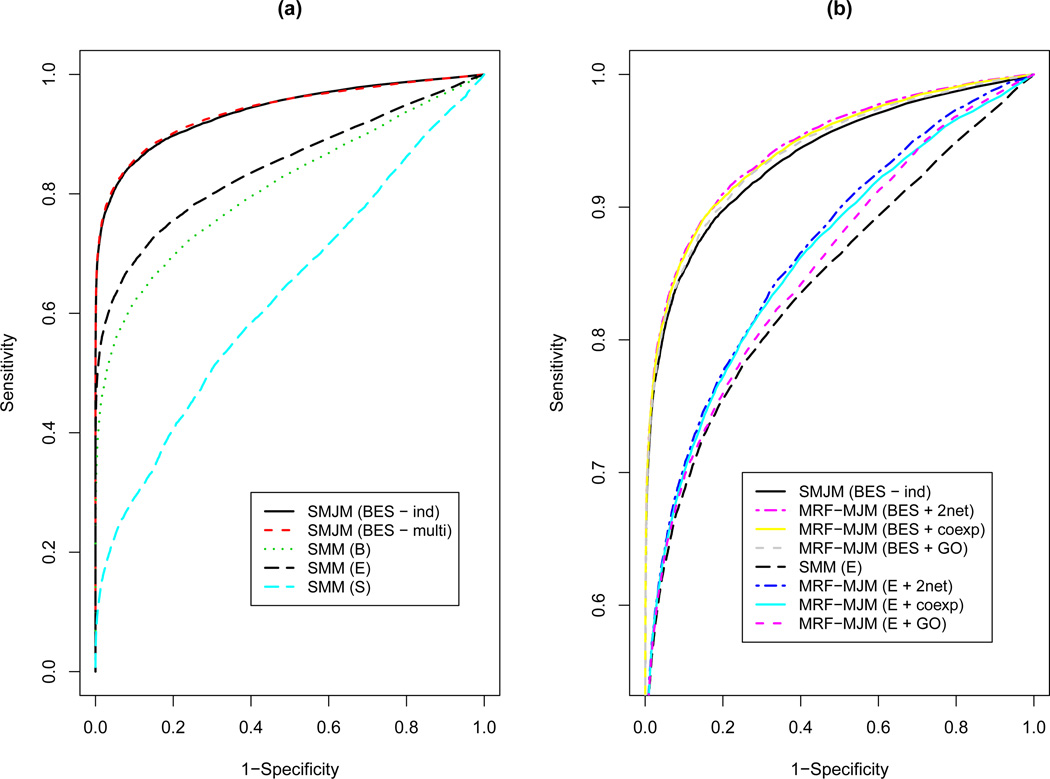

We simulated 20 data sets and applied the SMJM with an either general or diagonal conditional covariance structure and the MRF-MJM to each of the data sets. We used the ROC curves to compare the predictive performance. Figure 3 shows the ROC curves averaged across the 20 simulated data sets. When no network information was utilized, as shown in Figure 3(a), joint modeling of the three data sources, i.e., the SMJM with either covariance structure, had much higher predictive power than using a single source of genomic data. On the other hand, although the simulated binding and sequence data were considerably correlated for the target genes, assuming conditional dependence by adopting a general covariance structure hardly made any difference in terms of predictive power. This may be explained by the fact that the sequence data were the least informative among the three data sources, as suggested by the ROC curves, making the strong correlation between the binding and sequence data among the target genes much less important in terms of predictive power.

Figure 3.

ROC curves (averaged over 20 simulated datasets) for (a) modeling genomic data alone (“B” for binding, “E” for expression, ”S” for sequence, “multi” and “ind” for a general and a diagonal conditional covariance structure, respectively); (b) MRF-MJM (“GO” for GO-induced network, “coexp” for co-expression network, “2net” for both networks).

Incorporating gene networks via the MRF-MJM led to dominating ROC curves over those based on genomic data alone, as shown in Figure 3(b). Consistent with the real data analysis results, the improved power by the MRF-MJM was more dramatic for using the expression data alone than joint modeling of the three data sources. As pointed out by Wei and Pan (2010), the posterior probability of being a target in the MRF-based mixture models was jointly determined by the prior probability and the likelihood function, which depended on the gene networks and the observed genomic data, respectively. When the likelihood was very informative, such as the one for joint modeling of the three data sources here, it might dominate the prior probabilities, making the contribution of the gene networks less significant. In addition, when only one network was incorporated, the ROC curve for the co-expression network dominated that for the GO network, which was true in both scenarios, using expression data alone or combining three data sources, suggesting that the weight parameter β can be useful in comparing the “informativeness” of different gene networks. Finally, incorporating both networks resulted in improved predictive performance over using a single network, especially the GO network, demonstrating the flexibility and efficiency gains with the proposed MRF-MJM for integrating multiple gene networks.

6 Discussion

We have presented a flexible and powerful mixture model, based on the use of multiple MRFs, for integrating diverse types of genomic data and multiple gene networks to identify regulatory target genes of a TF. Rather than assuming conditional independence of ChIP-chip binding, gene expression and DNA sequence data, we allow multiple sources of data to be conditionally correlated. Due to a fully Bayesian approach, inference about model parameters can be easily carried out based on MCMC samples. Application to the LexA data, together with simulation studies, demonstrates the utility and statistical efficiency gains with the proposed joint model. An interesting biological finding is that the binding and sequence data were highly correlated for target genes only, which helps elucidate the regulation mechanism of LexA, an important TF involved in DNA repair in E. coli. Interestingly, ignoring the conditional correlations even led to slightly improved predictive performance. Our simulation study that mimicked the LexA real data confirmed that incorrectly assuming conditional independence did not result in deteriorated performance, possibly due to simpler models as well as only moderate predictive power of the sequence data. Further study on this problem is needed.

Although our application concerns identification of target genes of a TF in E. coli, it may be possible to adapt the proposed method to address other problems for other organisms, for example, identifying genes predisposing to complex human diseases by integrating multiple types of data such as SNP, epigenomic, gene expression, proteomic, metabolomic data and gene networks/pathways. It has been recently proposed to incorporate a single gene network into analysis of genome-wide association study (GWAS) data via a MRF model (Chen et al. 2011). In light of our study here, it would be interesting to consider multiple gene networks in network-based analysis of GWAS.

Based on the LexA data, we found that combining both gene networks might result in compromised predictive performance. This raises a question: shall we integrate as many gene networks as possible or choose to use the “best” gene network? If the former, as demonstrated by the simulation results, the MRF-MJM provides a very flexible and efficient framework to combine multiple networks by down-weighting more noisy ones. If the latter, how to compare gene networks is still an open question. A possible perspective is to look at the structural or topological differences between the networks. For example, as illustrated by Table 2 and Figure 1, the GO-induced network may be too dense, directly connecting many target and nontarget genes, and thus is less preferred compared to the co-expression network. On the other hand, the weight parameter β in the MRF-MJM has been demonstrated, by analyses of the LexA data as well as the simulation results, to be a promising criterion for quantitative comparison of gene networks. Nevertheless, considering that each of the gene networks contains partial yet complementary information about gene-gene interactions, integrating multiple networks is likely to achieve higher predictive power on average, for example, as measured by the area under the ROC curve (AUC). This could be a direction of future research.

While discrete MRFs were employed here to incorporate multiple gene networks, Gaussian MRFs (Wei and Pan 2008a, 2010) could be similarly used. However, unlike in (2), which is always between −1 and 1, the range of a similar term based on the Gaussian MRF would be the real line. As a result, it is unclear how to effectively assign weights to different networks based on the use of multiple Gaussian MRFs. This, together with assigning weights to different genomic data sources, would be an interesting topic for future investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers and the Editor for their helpful and constructive comments that improved the presentation of the paper. This research was partially supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL65462. The first author was also partially supported by a start-up fund from the University of Texas School of Public Health.

A APPENDIX

A.1 MCMC Algorithm for the MRF-MJM

We denote by (α| …) the full conditional of α, that is the distribution of α conditional on everything else in the model. In addition, we denote by MV N(μ, Σ) the multivariate normal distribution with mean vector μ and covariance matrix Σ, by ϕ(.;μ, Σ) the corresponding density function, and by W((ρR)−1, ρ) the Wishart distribution with mean R−1. The observed data are denoted as x = {xi = (Bi, Ei, Si)′; i = 1,…, G}. Model specification and prior distributions for the MRF-MJM can be found in Sections 3.3 and 3.4. In particular, p(T|Φ) is specified by the pseudolikelihood (3). As detailed below, we use Metropolis with Gibbs sampling to update Φ. The auxiliary variable-based Metropolis-Hastings algorithm of Moller et al. (2006) could be used to update Φ in the presence of the unknown normalizing constant C(Φ), which could, however, substantially slow down the computation, and is not pursued here.

The joint posterior distribution is

- update μ0 by Gibbs sampling with the proposal given by

where n0 = | {i : Ti = 0} |. - update θ by Gibbs sampling with the proposal given by

where n1 = | {i : Ti = 1} |. - update Σj, for j = 0, 1, by Gibbs sampling with the proposal given by

where μ1 = μ0 + θ. - update Ti by Gibbs sampling with proposal given by

where . - update Φ = (γ, β1, …, βK) using a random walk Metropolis algorithm with Gaussian proposal, which has diagonal covariance matrix. The acceptance ratio is calculated using the full conditional of Φ, which is proportional to

The Gaussian proposal was tuned such that the acceptance rate was around 0.23, the optimal one (Carlin and Louis 2008, page 131).

Contributor Information

Peng Wei, Division of Biostatistics and Human Genetics Center, University of Texas School of Public Health, Houston, TX 77030, USA, Peng.Wei@uth.tmc.edu.

Wei Pan, Division of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA, weip@biostat.umn.edu.

REFERENCES

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Elkan C. Unsupervised Learning of Multiple Motifs in Biopolymers using EM. Machine Learning. 1995;21:51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Besag J. On the statistical analysis of dirty pictures. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B. 1986;48:259–302. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KR, Jurisica I. Online predicted human interaction database. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2076–2082. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butala M, Zfur-Bertok D, Busby SJW. The bacteria LexA transcriptional repressor. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009;66:82–93. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8378-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin BP, Louis TA. Bayesian methods for data analysis. 3rd edition. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Cho J, Zhao H. Incorporating Biological Pathways via a Markov Random Field Model in Genome-Wide Association Studies. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(4):e1001353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirz RT, Chin JK, Andes DR, et al. Inhibition of mutation and combating the evolution of antibiotic resistance. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(6):e176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon EM, Liu XS, Lieb JD, Liu JS. Integrating regulatory motif discovery and genome-wide expression analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:3339–3344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630591100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courcelle J, Khodursky A, Peter B, Brown PO, Hanawalt PC. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2001;158:41–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum-likelihood with incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J Royal Stat Soc, Series B. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Deng MH, Chen T, Sun F. An Integrated Probabilistic Model for Functional Prediction of Proteins. Journal of Computational Biology. 2004;11(2/3):463–475. doi: 10.1089/1066527041410346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith JJ, Driscoll ME, Fusaro VA, Cosgrove EJ, Hayete B, Juhn FS, Schneider SJ, Gardner TS. Many Microbe Microarrays Database: uniformly normalized Affymetrix compendia with structured experimental meta-data. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36(Database issue):D866–D870. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke L, van Bakel H, Fokkens L, de Jong ED, et al. Reconstruction of a Functional Human Gene Network, with an Application for Prioritizing Positional Candidate Genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;78:1011–1025. doi: 10.1086/504300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama-Castro S, Jimenez-Jacinto V, Peralta-Gil M, Santos-Zavaleta A, et al. RegulonDB (version 6.0): gene regulation model of Escherichia coli K-12 beyond transcription, active (experimental) annotated promotersand Textpresso navigation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D120–D124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Rubin DB. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences (with discussion) Statistical Science. 1992;7:457–511. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen ST, Chen G, Stoeckert C. Bayesian Variable Selection and Data Integration for Biological Regulatory Networks. Annals of Applied Statistics. 2007;1:612–633. [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;28:2730. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshava Prasad TS, et al. Human protein reference database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;37:D767–D772. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Li H. Network-constrained regularization and variable selection for analysis of genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1175–1182. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel B. After 30 Years of Study, the Bacterial SOS Response Still Surprises Us. PLoS Biology. 2005;3(7):e255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller J, Pettitt AN, Berthelsen KK, Reeves RW. An efficient Markov chain Monte Carlo method for distributions with intractable normalising constants. Biometrika. 2006;93:451–458. [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Wei P, Khodursky A. A parametric joint model of DNA-protein binding, gene expression and DNA sequence data to detect target genes of a transcription factor; Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing 2008; 2008. pp. 465–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth FP, Hughes JD, Estep PW, Church GM. Finding DNA regulatory motifs within unaligned noncoding sequences clustered by whole-genome mRNA quantitation. Nat. Biotech. 1998;16:939–945. doi: 10.1038/nbt1098-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryden T, Titterington DM. Computational Bayesian analysis of hidden Markov models. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 1998;7:194–211. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter D, Thomas A, Best N, Lunn D. Win-BUGS User Manual, Version 1.4. 2003 Available at http://www.mrcbsu.cam.ac.uk/bugs/winbugs/manual14.pdf.

- Sun N, Carroll RJ, Zhao H. Bayesian error analysis model for reconstructing transcriptional regulatory networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7988–7993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600164103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade JT, Reppas NB, Church GM, Struhl K. Genomic analysis of LexA binding reveals the permissive nature of the Escherichia coli genome and identifies unconventional target sites. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2619–2630. doi: 10.1101/gad.1355605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Cherry JM, Nochomovitz Y, Jolly E, Botstein D, Li H. Inference of combinatorial regulation in yeast transcriptional networks: a case study of sporulation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:1998–2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405537102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P, Pan W. Incorporating gene networks into statistical tests for genomic data via a spatially correlated mixture model. Bioinformatics. 2008a;24:404–411. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P, Pan W. Incorporating gene functions into regression analysis of DNA-protein binding data and gene expression data to construct transcriptional networks; IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics; 2008b. pp. 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P, Pan W. Network-based genomic discovery: application and comparison of Markov random field models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics) 2010;59:105–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9876.2009.00686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Li H. A Markov Random Field Model for Network-based Analysis of Genomic Data. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1537–1544. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Li H. A Hidden Spatial-temporal Markov Random Field Model for Network-based Analysis of Time Course Gene Expression Data. Annals of Applied Statistics. 2008;2:408–429. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler G. Image Analysis, Random Fields and Markov Chain Monte Carlo Methods. 2nd edition. Springer: Berlin; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Su Z, Mao F, Olman V, Xu Y. Prediction of functional modules based on comparative genome analysis and Gene Ontology application. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2822–2837. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Pan W, Jeong KS, Xiao G, Khodursky KB. A Bayesian approach to joint modeling of protein-DNA binding, gene expression and sequence data. Statistics in Medicine. 2010;29:489–503. doi: 10.1002/sim.3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YH, Dudoit S, et al. Normalization for cDNA microarray data: a robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;304:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang APP, Pigli YZ, Rice PA. Structure of the LexA-DNA complex and implications for SOS box measurement. Nature. 2010;466:883–886. doi: 10.1038/nature09200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.