Abstract

Introduction

To evaluate the impact of a simple emergency department (ED)–based educational intervention designed to assist ED providers in detecting occult suicidal behavior in patients who present with complaints that are not related to behavioral health.

Methods

Staff from 5 ED sites participated in the study. Four ED staff members were exposed to a poster and clinical guide for the recognition and management of suicidal patients. Staff members in 1 ED were not exposed to training material and served as a comparator group.

Results

At baseline, only 36% of providers reported that they had sufficient training in how to assess level of suicide risk in patients. Greater than two thirds of providers agreed that additional training would be helpful in assessing the level of patient suicide risk. More than half of respondents who were exposed to the intervention (51.6%) endorsed increased knowledge of suicide risk during the study period, while 41% indicated that the intervention resulted in improved skills in managing suicidal patients.

Conclusion

This brief, free intervention appeared to have a beneficial impact on providers' perceptions of how well suicidality was recognized and managed in the ED.

INTRODUCTION

Suicidal patients represent an increasing proportion of emergency department (ED) volumes.1 In 2007, 472,000 people were treated in US EDs for self-inflicted injury.2 While the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention recognizes the ED as a practical setting for suicide prevention,3 for a variety of reasons, ED clinicians may not screen for or recognize suicidal patients.4 Suicide ideation is often not disclosed by ED patients and is often undetected during visits.5 Mental health patients that commit suicide often have attended an ED 1 or several times in the year prior to death.6 ED providers can play a pivotal role in suicide prevention, particularly in the identification of suicidal risk and behavior and linkage with treatment.7 Brief training has been shown to improve ED provider knowledge regarding suicidal behavior.8,9 This highlights the need for suicide prevention training and protocol enhancement for ED providers. However, ED-based efforts must be focused, clinically relevant, and delivered in a means that is acceptable to busy providers.

The uptake of new information by healthcare providers is critical to the advancement of clinical care. The translation of knowledge into effective patient care and policy, however, involves barriers at both practitioner and institutional levels, including the time constraints in acute care settings and the volume of information provided to practitioners.10 In emergency medicine, translating research to practice has been inconsistent.11 Implementing and uptake of practice guidelines can be complicated by the values and characteristics of the practitioners and patients, the clinical setting, and complexities of the specific practice guidelines.11–13

The objective of this multisite study is to evaluate the impact of a simple ED-based educational intervention designed to assist ED providers (attending and resident physicians, midlevel providers, and nurses) in detecting and addressing occult suicidal behavior in patients who present with complaints that are not related to behavioral health. We hypothesize that exposure to relevant educational material would result in increased provider awareness of potential ED patient suicidality and increased provider perception of their knowledge and skills to identify and treat suicidal ED patients.

METHODS

The educational intervention includes the use of a poster and clinical guide sponsored collaboratively by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center and the American Association of Suicidology and developed by a task force of behavioral health and ED clinician-researchers. The development process included multiple rounds of reviews and focus group testing by practicing ED physicians and nurses. The final product packet was composed of a poster, clinical triage guide, and implementation instructions distributed through the Emergency Nurses Association. Additionally, the materials have been distributed through state hospital associations as well as suicide prevention organizations. The study was supported by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center and was a cooperative effort of the Emergency Research Network in the Empire State (ERNES), a group of academic and community EDs throughout Western and Upstate New York and Northern Pennsylvania. During a 6-month period beginning in August 2009, providers in 4 ERNES EDs completed surveys detailing recognition and care of suicidal patients before and after exposure to training materials. Providers in 1 ED served as a comparator group, and completed the presurveys and postsurveys but did not receive the educational materials. Attitudes toward suicide and suicide prevention, related practice patterns, and perceived skills in suicide assessment were evaluated before and after dissemination of the training materials.

The study consisted of 3 phases including completion and collection of baseline surveys (phase 1, lasting 3 weeks), exposure to educational materials (phase 2, lasting 4 weeks), and completion and collection of follow-up surveys (phase 3, lasting 3 weeks). Surveys were made available to ED providers at each site in both paper form and online via Survey Monkey (SurveyMonkey.com, LLC, Palo Alto, California), an online survey tool, to facilitate as many responses as possible.

Before phase 1 and phase 3, study coordinators at each site provided instructions, distributed survey hard copies and invitation letters, and notified providers of the intervention. All providers were free to decline participation in the study. To obtain similar sample sizes across sites with varying numbers of providers, participation targets included a minimum of 80 providers at each site, including approximately one-third physicians, one-third midlevel providers, and one-third nurses. Surveys were anonymous; however, participants provided their own unique identification code to link baseline and follow-up surveys.

The director of each ED, or a designated study coordinator, distributed educational materials and managed each site's adherence to the study protocol, including the dissemination of study materials. After preliminary analysis, a postintervention survey was designed to assess if there were any additional trainings or enhancements to suicide prevention policy or processes at any ED sites during the study period. In this survey, ED directors or study coordinators were asked if they had done “anything during the intervention to highlight” or “improve” protocols for suicidal patients. The study was approved by the institutional review board of each site: Albany Medical Center (AMC), Erie County Medical Center in Buffalo, New York (ECMC), Robert Packer Hospital of Sayre, Pennsylvania (Guthrie Healthcare), SUNY Upstate University Hospital at Syracuse, New York (Syracuse), and the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC).

Description of the Intervention

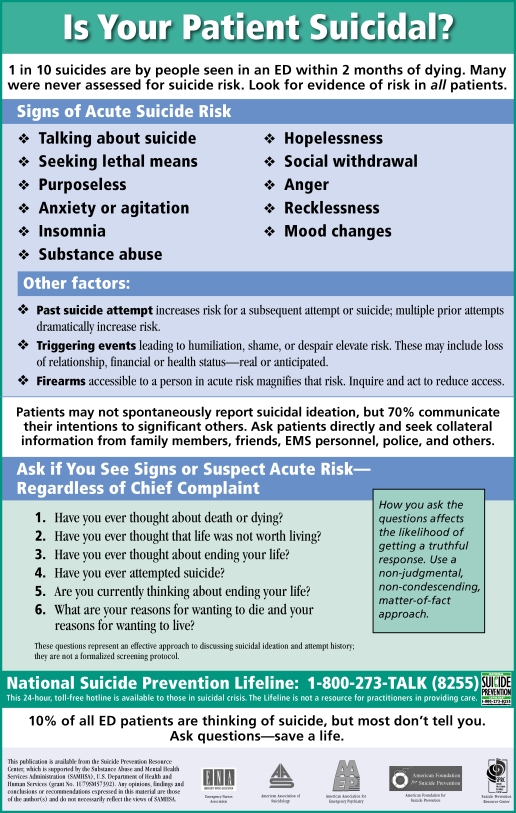

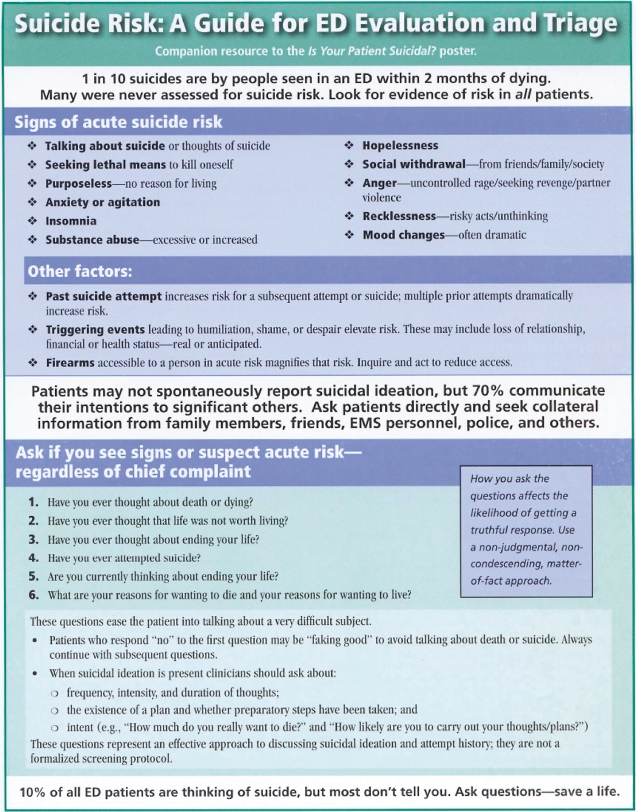

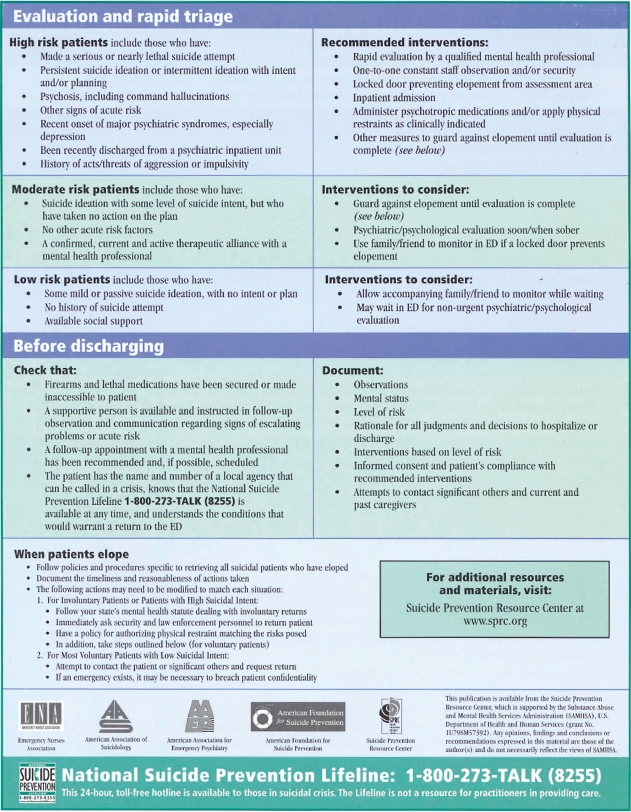

The intervention consisted of (1) a brightly colored, 11 × 17-inch poster mounted in the chart room or break room of each ED, and (2) distribution of an accompanying clinical guide to all ED providers. The “Is Your Patient Suicidal?” poster (Figure 1) provides suicide prevention information including signs of acute suicide risk, statistics, questions for use in detecting and discussing suicide ideation and prior attempts, and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number. The clinical guide, “Suicide Risk: A Guide for ED Evaluation and Triage,” (Figures 2 and 3) is a 1-page, double-sided companion resource to the poster that describes the poster content; additional questions for assessing suicidal ideation, plans, and intent; information on triage (high-risk patients, moderate-risk patients, low-risk patients, and recommended interventions); and discharge and documentation checklists. The posters were mounted for at least 4 weeks, the duration of phase 2.

Figure 1.

The “Is Your Patient Suicidal?” poster. ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical services.

Figure 2.

Front view of clinical guide for “Suicide Risk: A Guide for ED Evaluation and Triage”. ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical services.

Figure 3.

Back view of clinical guide for “Suicide Risk: A Guide for ED Evaluation and Triage”. ED, emergency department.

Inclusion Criteria

All physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and registered nurses at the ERNES ED sites were invited to participate in the baseline and follow-up surveys. Both male and female subjects were included in this study and all subjects were older than 18 years. Subjects' racial and ethnic origins reflected that of ED providers.

Exclusion Criteria

There were no exclusion criteria for this study.

Data Analysis

The results of each survey question were tabulated and reported in absolute numbers and proportions. Attending physicians were categorized as “physicians”; residents and fellows, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners were categorized as “supervised providers”; and nurses were categorized as “nurses.” Chi-square tests were used to compare differences in proportions for dichotomous categorical variables. To conserve sample size, in some instances 5-point Likert scales (1, strongly disagree–5, strongly agree) were dichotomized to agree (4, 5)/not agree (1, 2, 3) or disagree (1, 2)/not disagree (3, 4, 5). We further performed analyses of respondents who reported recalling exposure to the training materials (exposed) versus those who did not (unexposed). Postintervention responses were compared between participants at intervention sites and participants at the comparator site. All tests were 2-tailed and used a 0.05 significance level. Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

Five EDs participated in the study: AMC, ECMC, Guthrie Healthcare, Syracuse, and URMC.

A total of 362 subjects completed the baseline survey and 250 subjects (69.1%) completed the follow-up survey. The 5 participating ED sites had approximately 650 physician, midlevel, and nurse providers in total. The overall baseline response rate for the study was thus approximated to be 55.7% (362/650). Response rates per provider type were approximately 58.4% (73/125) for physicians, 61.4% (118/192) for mid-level providers, and 51.4% (171/333) for nurses. More than one half of baseline surveys (51.1%) and follow-up surveys (54.0%) were completed online. Combined totals for the baseline and follow-up surveys per site ranged from 203 at AMC to 49 at Syracuse, with URMC completing 166, ECMC completing 136, and Guthrie completing 58 surveys each.

Fewer than 1% of subjects reported specialty training in psychiatry. About 60% reported providing direct care primarily to adults, 8% primarily to children, and 32% to both children and adults.

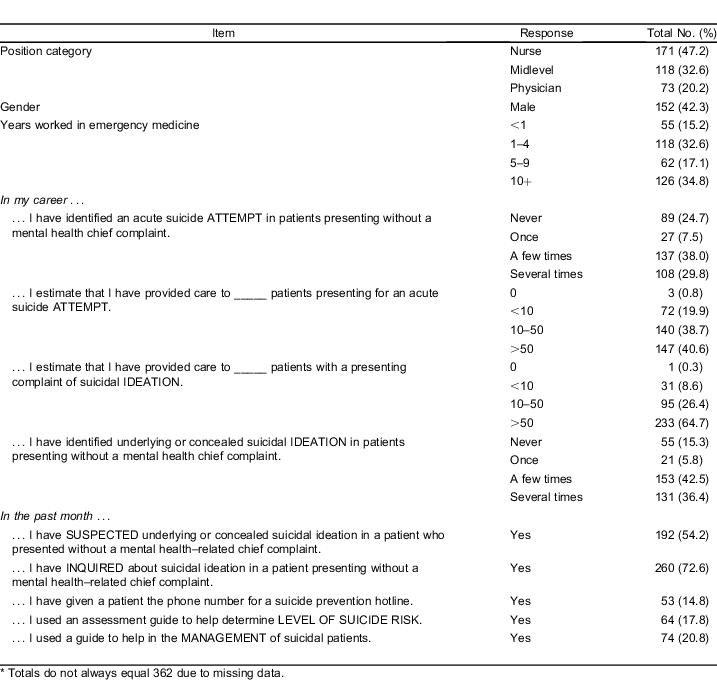

Other selected baseline provider characteristics and baseline provider experience variables are displayed in Table 1. Approximately 80% of providers reported that in their careers they had provided care to at least 10 “patients presenting for an acute suicide attempt.” At baseline, 36.4% of respondents endorsed having detected acute suicidal thoughts in several patients who presented to the ED for medical complaints. About one half of providers had 5 or more years of ED experience.

Table 1.

Baseline provider characteristics and experience.*

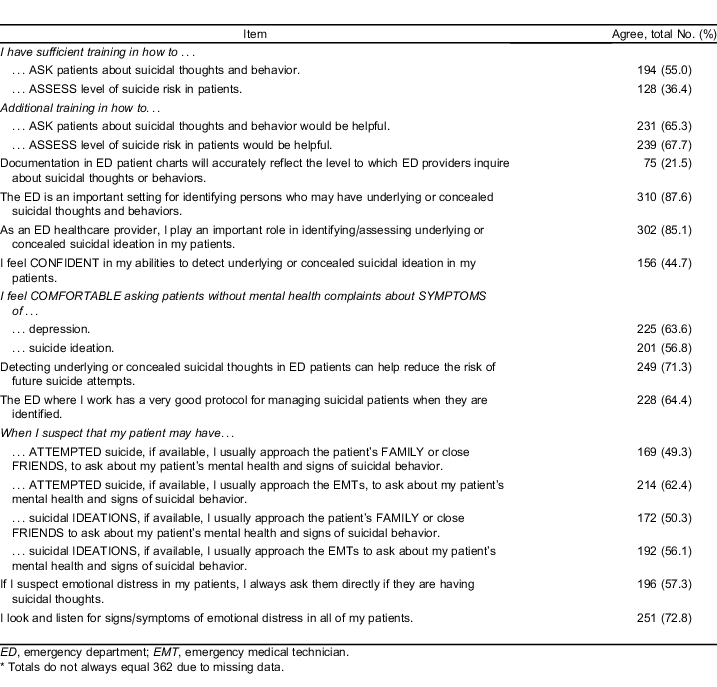

Table 2 shows totals of baseline data on provider training, attitudes, and beliefs about care of suicidal patients. Only 36% of providers reported that they had “sufficient training in how to assess level of suicide risk in patients.” Greater than two thirds of providers agreed that additional training “would be helpful” in assessing the level of patient suicide risk.

Table 2.

Baseline provider training/attitudes/beliefs.*

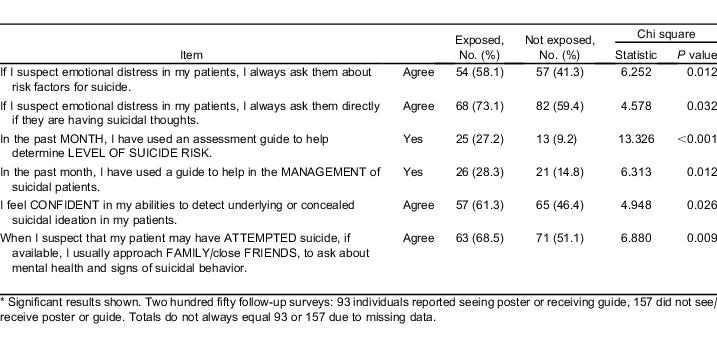

Of the 218 subjects at intervention sites that completed follow-up surveys, 93 recalled exposure to either the poster or the clinical guide (42.7%). Table 3 shows significant results for comparisons between exposed and unexposed (n = 157) follow-up subjects. Exposed subjects more readily endorsed that if they suspect emotional distress in their patient, they “always ask them about risk factors for suicide” (58.1% vs 41.3%; χ2 = 6.3, P = 0.012) and that they “always ask them directly if they are having suicidal thoughts” (73.1% vs 59.4%; χ2 = 4.6, P = 0.032). Approximately 10% of providers in both groups reported they had given a patient a suicide prevention hotline number. Significantly more exposed providers reported using an assessment guide to help determine level of suicide risk than unexposed providers (27.2% vs 9.2%; χ2 = 13.3, P < 0.001). Also, significantly more exposed providers reported using a guide to help manage suicidal patients than unexposed providers (28.3% vs 14.8%; χ2 = 6.3, P = 0.012).

Table 3.

Chi-square test comparison of follow-up provider surveys, exposed versus not exposed.*

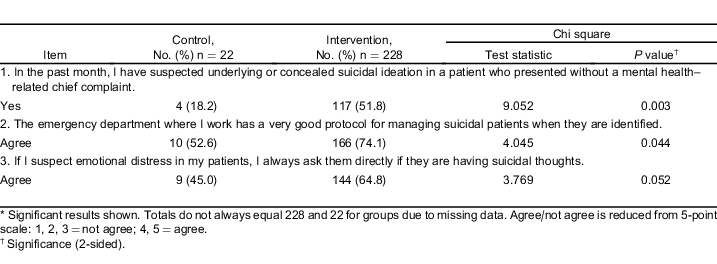

The comparator group (ED not provided education materials at phase 2) included 22 follow-up subjects. As shown in Table 4, slightly more than half of intervention site subjects reported they “suspected underlying or concealed suicidal ideation in a patient who presented without a mental health–related chief complaint” in the past month, compared to fewer than one fifth of clinicians in the comparator site (51.8% vs 18.2%; χ2 = 9.1, P = 0.003). Interestingly, a higher proportion of intervention site subjects relative to comparator subjects agreed with the statement, “The ED where I work has a very good protocol for managing suicidal patients when they are identified” (74.1% vs 52.6%; χ2 = 4.0, P = 0.044).

Table 4.

Chi-square test comparison of comparator site and intervention sites, follow-up survey responses.*

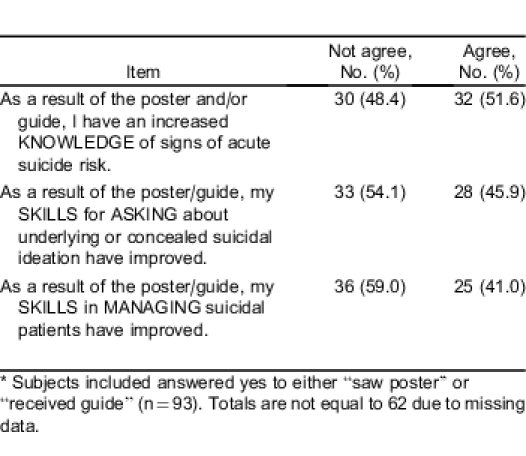

Table 5 shows the impact of the intervention on knowledge and skills for managing suicide for subjects who recalled exposure to the intervention. More than half of exposed follow-up subjects (51.6%) reported that, as a result of the intervention, they had “an increased knowledge of signs of acute suicide risk”; 45.9% reported that their “skills for asking about underlying or concealed suicidal ideation have improved”; and 41.0% reported that their “skills in managing suicidal patients have improved.” In response to the postintervention survey, no directors or study coordinators reported any changes or emphasis on protocols during the intervention.

Table 5.

Gaining knowledge and skill questions (subjects exposed to intervention).*

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that significant improvements in self-reported practice patterns can be achieved through the simple intervention of hanging a wall poster and distributing a 1-page clinical guide to ED clinicians. For instance, providers that were exposed to the educational materials in this intervention were more likely to report that they inquired about suicide risk and suicidal thoughts. Subjects at intervention sites compared to comparator sites more frequently reported suspecting concealed suicide ideation in their patients. Clinicians exposed to the educational material were also more likely to directly inquire about suicide thoughts in patients they suspected were in emotional distress and were more likely to use a guide in making risk assessments and managing suicidal patients. These differences were evident despite low reporting of exposure to the educational materials at intervention sites, suggesting that introducing an educational intervention on suicide in an ED can influence provider attitudes and behaviors for those not reporting direct exposure to the material. This could suggest informal augmentation of suicide prevention awareness and attention to identification among ED providers.

Survey responses generally underscore the importance of assessing and implementing suicide prevention in the ED. Clinicians generally indicated feeling comfortable asking patients about concealed symptoms of depression and suicidality. Yet, the responses also revealed that subjects felt ED providers may be unaware of potential mental health issues if the patient does not present with specific mental health complaints. More than 1 of 7 providers (15.3%) reported they had never identified underlying or concealed suicide ideation in patients who did not present to the ED with a chief mental health complaint. Providers did not feel the extent of suicidality assessments was accurately documented in ED records. Overall, most providers agreed that additional training in how to ask about and assess suicidal thoughts and risk would be helpful.

Of note, clinicians at intervention sites were more likely to report that their ED had good protocols in place for managing suicidal patients. The results of the postintervention survey indicated this was not due to any enhancements.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations to this study that may reduce generalizability of findings to other settings. We did not assess differences in preintervention management of suicidal patients across sites. The method used to link individual subject baseline and follow-up surveys, by subject-supplied unique identification codes, was variably effective by site. Many subjects entered different codes for the baseline and follow-up surveys, thus linking the surveys was not possible. Without linked data for preintervention and postintervention and without specific provider information in the follow-up survey, measurement of response bias also is limited. Furthermore, many providers at intervention sites did not report being exposed to the interventions. Providers that were originally more inclined to integrate suicide and mental health–related inquires in their ED assessments may have been more inclined to review the educational materials and subsequently report exposure to them. Other limitations include the fact that the study and results reflect the perceptions of ED providers regarding care for suicidal patients and did not measure patient outcomes and the fact that only 1 comparator site was used. Moreover, the ability to maintain the effects demonstrated in this study over time is unclear without a longer period of assessment.

CONCLUSION

Providers that individually received educational materials and providers at ED sites where the materials were available both indicated increased awareness of potential suicidality in ED patients. Overall, the intervention increased or improved provider perception of their knowledge and skills regarding identification and treatment of suicidality for approximately half of the providers receiving the guide or seeing the poster. ED providers generally feel that the ED is an important setting for identifying concealed suicidality in patients, that they can be a significant participant in this process, and that additional training in how to recognize patient suicidality is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Suicide Prevention Resource Center is supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Leslie Zun, MD

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding, sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

REFERENCES

- 1.Larkin GL, Claassen CA, Emond JA, et al. Trends in U.S. emergency department visits for mental health conditions, 1992 to 2001. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:671–677. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niska R, Bhuiya F, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 Emergency Department Summary: National Health Statistics Reports, No. 26. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics;; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baraff LJ, Janowicz N, Asarnow JR. Survey of California emergency departments about practices for management of suicidal patients and resources available for their care. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claassen CA, Larkin GL. Occult suicidality in an emergency department population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:352–353. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruz D, Pearson A, Saini P, et al. Emergency department contact prior to suicide in mental health patients. Emerg Med J. 2010;28:467–471. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.081869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Piacentini J, Cantwell C, et al. The 18-month impact of an emergency room intervention for adolescent female suicide attempters. J Consul Clin Psychol. 2000;68:1081–1093. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horwitz SM, Heinberg LJ, Storfer-Isser A, et al. Teaching physicians to assess suicidal youth presenting to the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:601–605. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31822255a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shim RS, Compton MT. Pilot testing and preliminary evaluation of a suicide prevention education program for emergency department personnel. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46:585–590. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein SL, Bernstein E, Boudreaux ED. et al. Public health considerations in knowledge translation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:1036–1041. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham ID. Tetroe J; KT Theories Research Group. Some theoretical underpinnings of knowledge translation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:936–941. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lang ES, Wyer PC, Haynes B. Knowledge translation: closing the evidence to practice gap. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Compton S, Lang E, Richardson TM, et al. Knowledge translation consensus conference: research methods. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:991–995. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]