Abstract

The dystrophin–glycoprotein complex connects myofibers with extracellular matrix laminin. In Duchenne muscular dystrophy, this linkage system is absent and the integrity of muscle fibers is compromised. One potential therapy for addressing muscular dystrophy is to augment the amount of α7β1 integrin, the major laminin-binding integrin in skeletal muscle. Whereas transgenic over-expression of α7 chain may alleviate development of muscular dystrophy and extend the lifespan of severely dystrophic mdx/utrn−/− mice, further enhancing levels of α7 chain provided little additional membrane integrin and negligible additional improvement in mdx mice. We demonstrate here that normal levels of β1 chain limit formation of integrin heterodimer and that increasing β1D chain in mdx mice results in more functional integrin at the sarcolemma, more matrix laminin and decreased damage of muscle fibers. Moreover, increasing the amount of β1D chain in vitro enhances transcription of α7 integrin and α2 laminin genes and the amounts of these proteins. Thus manipulation of β1D integrin expression offers a novel approach to enhance integrin-mediated therapy for muscular dystrophy.

INTRODUCTION

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is one of the most prevalent hereditary diseases of humans. It is caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene, the largest human gene (1). The dystrophin–glycoprotein complex is a transmembrane linkage system that connects the cell cytoskeleton to laminin in the basal membrane surrounding muscle fibers (2,3). In the absence of dystrophin and the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex, the integrity of the sarcolemma is compromised and muscle weakness and pathogenesis develop (for review, see 4).

Integrins are another family of molecules that connect the extracellular matrix and actin cytoskeleton (5,6). The α7β1 integrin is the major laminin-binding integrin in skeletal muscle (6,7). During skeletal muscle development, this integrin functions in myoblast adhesion, migration, proliferation and differentiation (7–11). Upon maturation of myofibers, the α7β1 integrin is localized along the sarcolemma and it is concentrated at costameres, myotendinous junctions (MTJs) and neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) (7,12). The integrin plays a pivotal role in maintaining stable connections at these specialized sites of contact between myofibers and the extracellular matrix that are needed to receive and transmit signals and withstand contractile forces. The α7β1 integrin also functions in signal transduction as a mechanoreceptor, and it protects muscle against exercise-induced damage (11,13). Thus, the α7β1 integrin is essential for maintaining muscle integrity and stabilizing connections between the sarcolemma and extracellular matrix.

The pivotal roles of α7β1 integrin in skeletal muscle are also manifest clinically. Mutations in the α7 integrin gene result in human congenital myopathies (14) and experimental disruption of the α7 gene in mice leads to progressive muscular dystrophy (14–16). Decreased amounts of the α7β1 integrin are often secondarily associated with muscular dystrophies/myopathies of unknown etiology (17,18). In both Duchenne patients and in mdx mice, elevated levels of the α7β1 integrin have been detected and are thought to compensate for the absence of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex (7,19,20). Indeed, transgenic enhancement of α7 chain levels can alleviate severe muscular dystrophy in mdx/utrn−/− mice (21,22). These mice lack both dystrophin and its homolog, utrophin, and they exhibit a severe dystrophic phenotype akin to that seen in Duchenne patients (23,24). As predicted, mdx/α7−/− mice, lacking both the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex and α7 integrin, exhibit an even more severe muscle wasting (25–27). These results suggest that the α7β1 integrin and the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex have complementary roles in maintaining the functional integrity of skeletal muscle.

The diverse functions of the α7β1 integrin are achieved by generation of multiple alternative spliced variants of both α7 and β1 mRNAs (for review, see 7). The α7 integrin has both alternative cytoplasmic tails (α7A and α7B) and extracellular domain isoforms (α7×1 and α7×2) (7,8,28–30). These cytoplasmic tails differ in their length, signaling potential and binding partners. α7B is expressed in both myoblasts and myofibers, and it has also been detected in the heart, vascular smooth muscle, neurons and Schwann cells. α7A is concentrated at the NMJ and MTJ of muscle fibers where it maintains membrane integrity (7,12,31). Similarly, the extracellular domain isoforms of α7 also differ in distribution and in their specificity and affinity for different isoforms of laminin (7,9). Like the α7 chain, the β1 subunit also has several cytoplasmic domain isoforms that result from alternative RNA splicing (32–34). During early muscle development, β1A integrin is the major isoform in myoblasts, whereas in adult muscle fibers β1D is the predominant form and mediates a stronger interaction with laminin (35,36). Experimental knockout of β1 integrin results in embryonic lethality and further demonstrates the essential role of β1 integrin in cell–extracellular matrix interactions during embryonic development (37,38).

The β1 subunit is the only integrin β chain known to form functional heterodimers with α7 chains (6,7,39). Normally, integrin heterodimers are formed in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and are targeted to the cell membrane after undergoing post-translational modifications in the Golgi (40–43). When one subunit is in excess, the extra subunits, associated with chaperon proteins, remain in the ER in a pre-mature form and await dimerization with other subunits (40,42). Therefore, maintaining the stoichiometry of the α and β subunits is key to the formation of appropriate amounts of integrin receptors on the cell surface.

We previously demonstrated that enhancing the amount of α7β1 integrin in mdx/utrn−/− mice expands their life span ∼3-fold and partially prevents the progression of the dystrophy (21,22). However, the highest level of increased α7 expression achieved in mdx/utrn−/− animals was only ∼2-fold and this suggested that the full beneficial effect of increasing the integrin-mediated trans-sarcolemma linkage was restricted. Moreover, little reduction of disease was seen when α7 chain was increased up to 6-fold in δ-sarcoglycan null mice that also have disrupted DGC complexes and display a milder dystrophy (44). In wild-type mice, expression of α7 integrin was enhanced up to 8-fold without any apparent overt negative effects, however staining of skeletal muscle fibers revealed sarcoplasmic retention of the excess α7 protein (45). This sarcoplasmic retention of excess α7 protein was also seen in α7 transgenic δ-sarcoglycan null mice (44). These results suggest that the amount of α7β1 integrin and its localization are limited in normal and dystrophic skeletal muscle. The most obvious potential limiting factor is the amount of β1 subunit.

In this study, we show that in α7 transgenic wild-type mice, the excess α7 chain is retained inside the muscle fibers due to the limiting amount of β1 protein. Increasing the availability of β1D chain by virus-mediated infection targeted the excess α7 chain to the muscle sarcolemma and more laminin was detected around the infected muscle fibers. Moreover, increasing the amount of β1D chain in mdx mice protected muscle fibers from developing membrane damage and simultaneous enhancement of α7 and β1D chain levels afforded even better protection. These results demonstrate the importance of targeting muscle membrane protein complexes to the sarcolemma in developing therapies to alleviate muscular dystrophy and suggest that increasing the levels of both the α7 and the β1 integrin chains is important to achieving the maximal beneficial effects of integrin-mediated alleviation of muscular dystrophy. In addition, cell culture studies indicate that increasing the amount of β1D chain in vitro enhances transcription of the α7 integrin and α2 laminin genes and the amounts of these proteins. Thus manipulation of β1D gene expression offers a novel approach to integrin-mediated therapy.

RESULTS

High levels of α7 integrin chain alone do not prevent muscular dystrophy in mdx mice

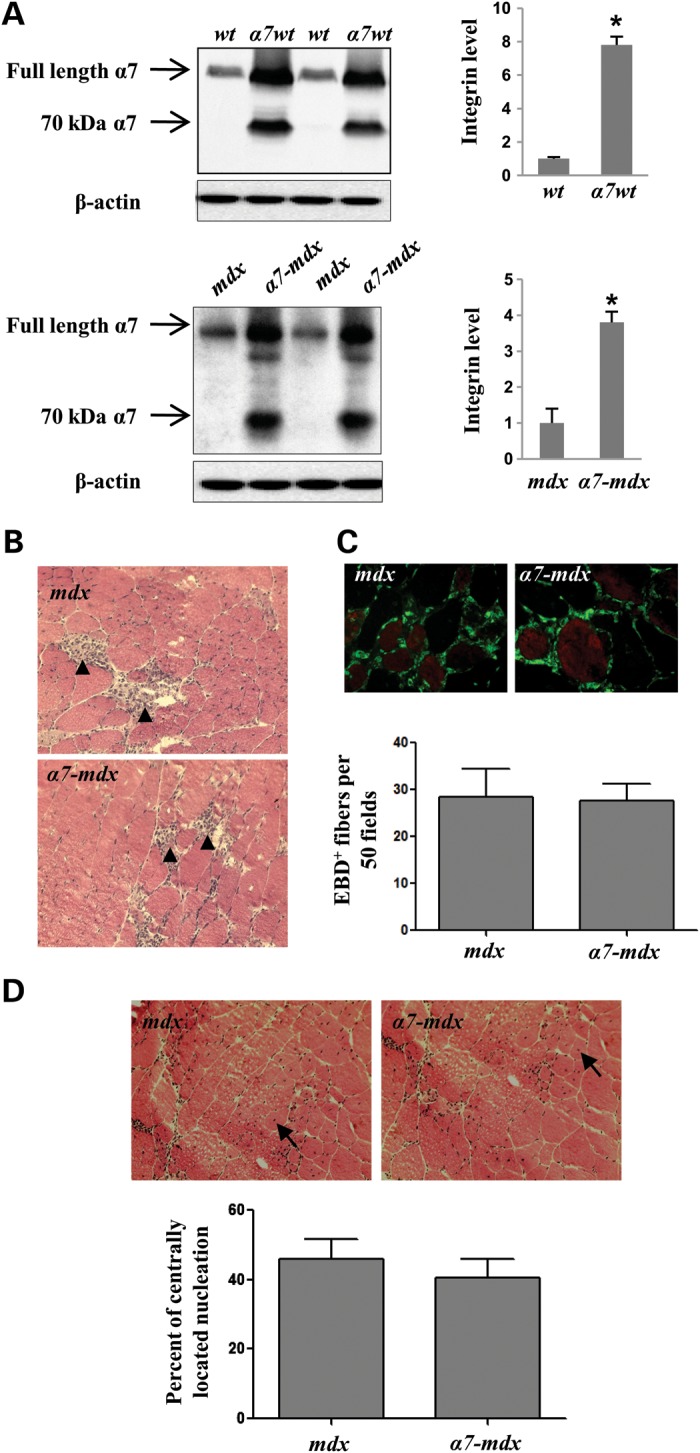

Previously we showed that 2-fold increases in α7 integrin levels can greatly alleviate development of the dystrophic phenotype in mdx/utrn−/− mice (21,22). Here we examined whether similar beneficial effects of increasing α7 chain could be observed in mdx mice. Wild-type α7 transgenic mice (α7wt) mice (11,45) expressing 8-fold more integrin were bred with mdx mice to obtain α7-mdx mice. Western blots revealed 4-fold more α7 integrin in α7-mdx mice compared with mdx mice (Fig. 1A). In contrast, attempts to further increase transgenic expression of the integrin >2-fold in mdx/utrn−/− mice were not successful (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1B), thus further enhancement of α7 integrin levels in these severely dystrophic mice appears to be limited. Therefore to develop an effective integrin-based therapy for Duchene muscular dystrophy, it would be beneficial to identify what may limit increasing the level of α7β1 integrin in the membrane of dystrophic muscle.

Figure 1.

Transgenic expression of α7 integrin in mdx mice does not prevent muscular dystrophy. (A) Western blots of protein extracts from gastrocnemius-soleus muscles of α7 transgenic wild-type (α7wt), α7 transgenic mdx (α7-mdx) and their control counterparts (n = 5 per genotype). As indicated by arrows, using a rabbit polyclonal antibody, both full length and a 70 kDa band (resulting from the proteolytic cleaved of the rat α7 integrin) were detected in α7wt and α7-mdx mice (73). β-Actin was used as loading control. An 8-fold increase of α7 was detected in α7wt compared with wild-type mice and a 4-fold increase was detected in α7-mdx compared with congenic mdx mice. *P < 0.001. (B) H&E staining of muscle fibers from mdx and α7-mdx mice reveals similar inflammation (arrowheads) in their gastrocnemius muscles. (C) Transgenic expression of α7 integrin does not protect sarcolemmal integrity of mdx mice. Immunofluorescence images of mdx and α7-mdx gastrocnemius muscles injected with EBD. Muscle fibers were delineated by FITC-WGA. Quantification of EBD-positive fibers reveals no significant differences between mdx and α7-mdx mice. The average numbers of EBD-positive fibers per 50 random fields, using the ×40 objective, are indicated. At least three sections for each animal were quantified. Five animals per group. (D) H&E staining of mdx and α7-mdx muscle shows the presence of similar levels of centrally located nuclei (arrows). Quantification demonstrates no significant differences in the percent of muscle fibers with centrally located nuclei in mdx and α7-mdx mice. At least three sections for each animal were quantified. Five animals per group.

Mdx mice exhibit significant muscle degeneration at 6 weeks of age (46), and enhancing their expression of α7 chain did not alter that (Fig. 1B–D). No significant differences in muscle histology were detected in mdx and α7-mdx mice and both had abundant regions of inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 1B). Likewise, the uptake of Evan's blue dye (EBD) to assess sarcolemmal damage indicated similar numbers of EBD-positive fibers in the mdx and α7-mdx muscle (Fig. 1C). Centrally located nuclei result from the degeneration and subsequent regeneration of dystrophic muscle, and their quantity is often used as an index of this process (47–52). Comparison of central nucleation in mdx and α7-mdx mice also revealed no significant differences (Fig. 1D). Thus increasing α7 chain up to 4-fold did not prevent the development of pathology or muscle fiber degeneration and regeneration in mdx mice.

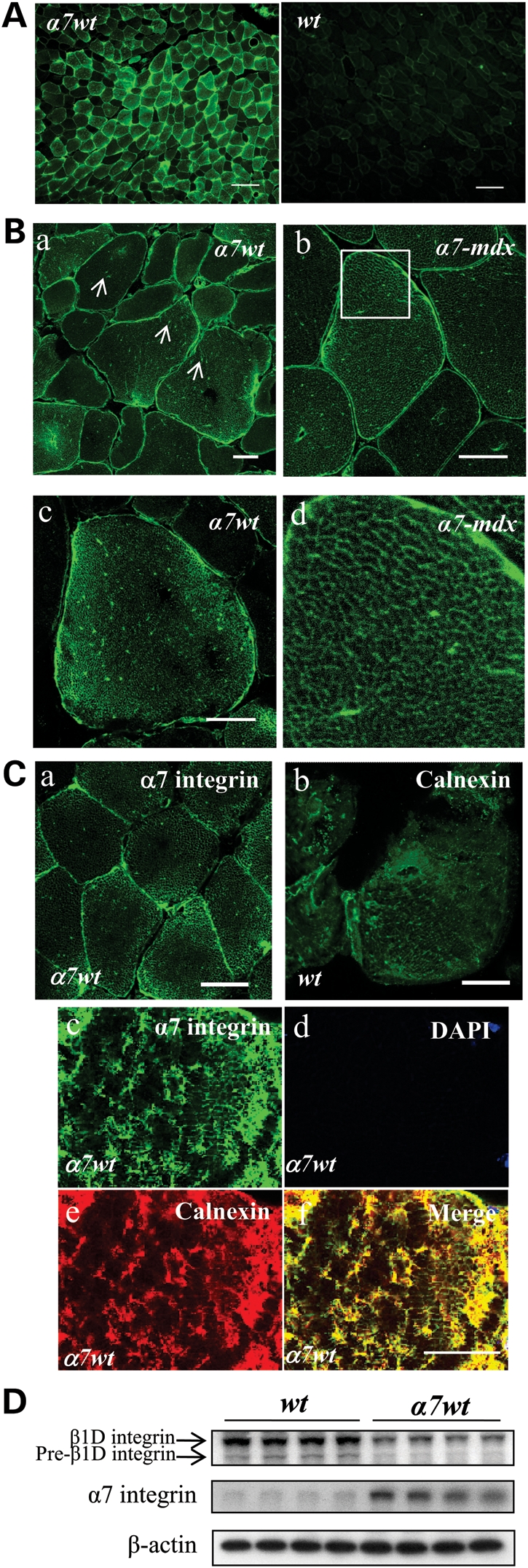

Excess α7 chain is retained in the ER of myofibers due to limited amounts of β1D

When α7 chain is over-expressed, increased levels of the integrin were detected at the sarcolemma (Fig. 2A) and at MTJs and NMJs (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). However, unlike non-transgenic controls, α7wt and α7-mdx transgenic skeletal muscle also exhibited punctate localization of α7 inside the myofibers (Fig. 2B). Higher magnification confocal images revealed a staining pattern of the α7 chain (Fig. 2Bc and Bd) similar to the ER which can be identified by calnexin (Fig. 2Cb), a marker for the ER (53). Confocal z-stack series images demonstrating α7 staining pattern in transgenic wild-type mice are available in Supplementary Material, Movie S1. In addition, double staining of α7 integrin and calnexin in α7 transgenic mice also reveals their co-localization inside the muscle fibers (Fig. 2Cc–f, and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1C). These results suggest that α7 protein is retained in the ER of the transgenic muscle fibers. Normally, integrin heterodimers form in the ER and are transported through Golgi to the cell membrane (40,42). Although β1 integrin chain is usually synthesized in excess and stored in the ER (40,42), the internal staining of α7 implies a relative shortage of β1 subunits in the α7 transgenic myofibers. Thus, in the absence of sufficient β1 subunits, excess α7 chains accumulate in the muscle ER. In addition, whereas the amount of both α7 integrin mRNA and protein are increased in Duchenne patients and in mdx mice (20), there is no parallel increase of the β1D chain (54,55). Nevertheless, in these cases, the normal reservoir of β1 chain appears to be sufficient to increase levels of the α7β1 integrin in the sarcolemma, albeit by only ∼2.0-fold, as reported in α7 transgenic mdx/utrn−/− mice (21).

Figure 2.

Excess α7 integrin chain is retained inside skeletal muscle fibers of transgenic mice. (A) Immunofluorescence images of gastrocnemius muscle of 5-week-old α7 transgenic mice (α7wt) and wild-type control mice (wt) using antibody recognizing both endogenous and transgenic rat α7 integrin. Bar = 100 µm. (B) Confocal images of α7 localization in the gastrocnemius muscles of 5-week-old α7 transgenic wild-type (α7wt) and α7 transgenic mdx (α7-mdx) mice. (a) Arrows indicate punctate α7 staining in α7wt skeletal muscle fibers. (b) Similar staining patterns were observed in transgenic α7-mdx mice. (c) High magnification confocal images of α7wt muscle fibers reveal a network-like staining of α7 integrin inside the muscle fiber. (d) Area in white box in (b) magnified to reveal detailed α7 staining in individual muscle fibers. (C) Confocal images of α7 localization in transgenic animals (a) are compared with the ER distribution of calnexin inside muscle fibers (b). (c–f) Co-localization of α7 integrin and calnexin in α7 transgenic mice was confirmed by double immunofluorescence staining, suggesting that excess α7 integrin chains are localized to the ER. Bar = 25 µm. (D) Western blots for total β1D chain (under reducing conditions) demonstrate reduced levels of β1D and the loss of the pre-mature form of β1 integrin in α7 transgenic mice. β-Actin was used as loading control. Four animals for each genotype.

In α7 transgenic wild-type mice that express 8-fold more α7 chain than their controls, both immunofluorescence and western blots demonstrate a slight decrease in β1 chain (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). Interestingly, western blots in reducing conditions demonstrated a lack of the premature form of β1D integrin (Fig. 2D). The limiting amounts of β1D chain appear to restrict the formation and localization of functional α7β1 integrin and resultantly limit the beneficial effects of enhanced α7 expression in dystrophic muscle. Therefore, increasing β1 chain levels may promote localization of more functional integrin at the sarcolemma and thereby better alleviate development of the dystrophic phenotype.

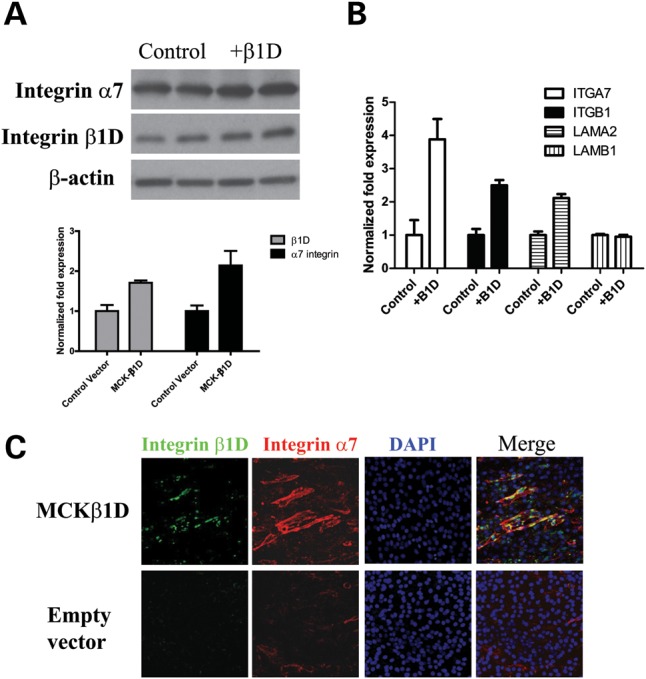

Increasing β1D chain in C2C12 cells selectively promotes expression of the ITGA7 and LAMA2

We therefore examined the effects of increasing β1D chain on the expression of α7 chain and laminin in normal C2C12 myoblasts. Because β1D integrin inhibits myogenic differentiation (56), we expressed it in C2C12 cells under the control of a modified muscle creatine kinase promoter (MHCK) that is utilized after differentiation. C2C12 cells were differentiated for 3 days after transfection. In addition to the increased level of β1D chain, quantification of western blots also demonstrates a corresponding increase in the amount of α7B chain (Fig. 3A). This increase of α7 chain is likely due to enhanced transcription as quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) indicates an ∼4-fold increase in α7 integrin mRNA (Fig. 3B). In addition, we observed an increase of laminin α2 but not laminin β1 mRNA. Both laminin α2 and laminin β1 are components of laminin 2, the major integrin ligand in the basal membrane of muscle fibers. Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that the increase of surface α7 integrin occurred only in cells over-expressing β1D (Fig. 3C). The effects of increasing β1D in C2C12 cells engineered to express rat α7BX2 integrin chain under the control of a MHCK promoter (BX2–C2C12 cells) (57,58) was also examined. Adenovirus containing human β1D cDNA (Ad-β1D), driven by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (59), was used to enhance expression of β1D chain in these cells. As before, an increase of rat α7 integrin was detected at the cell surface using an anti-rat α7 integrin specific antibody (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3B). These results suggest that expression of cell surface integrin is highly regulated in muscle cells and increasing the amount of β1D chain may promote a corresponding increase in the amounts of α7 and laminin subunits in skeletal muscle. In contrast, in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes, increasing expression of β1D chain does not promote an increase in α7 levels, thus the coordinate regulation of these two integrin subunit may be cell type specific (personal communication, R.S.R.).

Figure 3.

Enhanced β1D levels in C2C12 cells increases the amounts of α7 integrin and laminin α2 protein and transcripts. (A) Western blots of α7 and β1D chains in 3-day differentiated C2C12 cells transfected with α-MHCK-β1D plasmid. Quantification of western blots using Imagequant software demonstrates a 1.7-fold increase of β1D in myotubes and an ∼2-fold increase in α7B chain. (B) Quantitative RT–PCR analysis of 3-day differentiated C2C12 cells transfected with α-MHCK-β1D plasmid. Increasing the amount of β1D chain results in a 4-fold increase in α7 integrin transcripts and an ∼2-fold increase in laminin α2 transcripts. The mRNA level of laminin β1 was not altered. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of surface integrin (red) in α-MHCK-β1D (green) transfected C2C12 myotubes. More integrin was detected at the surface of mytotubes over-expressing β1D compared with control C2C12 myofibers.

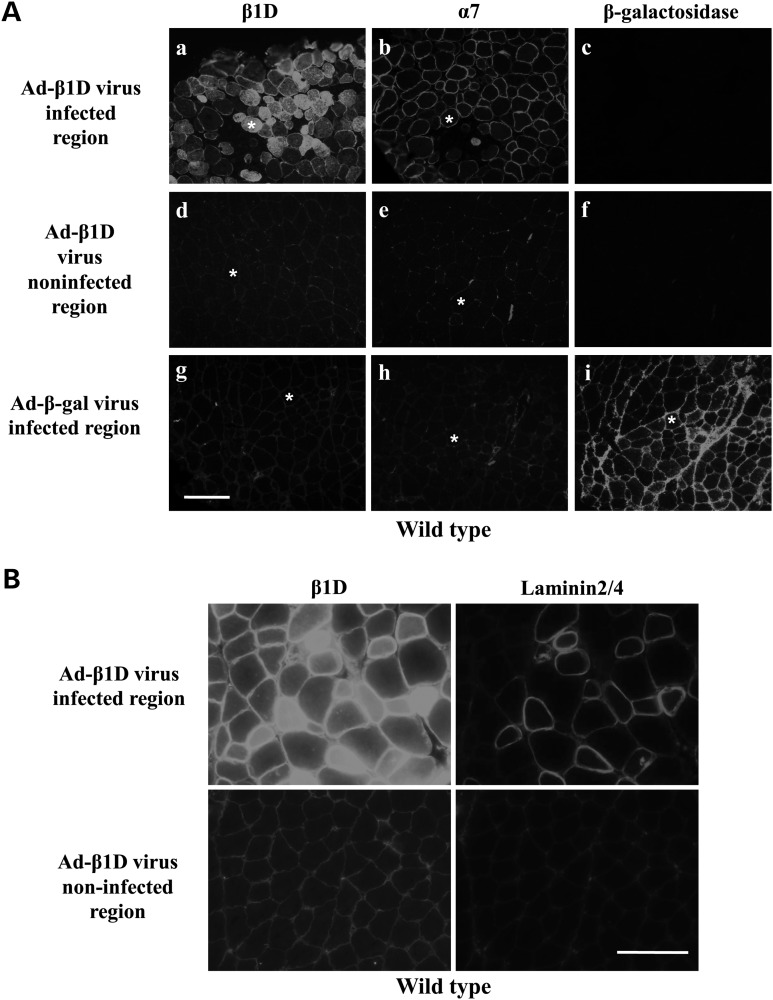

Increasing β1D chain results in more α7β1 integrin at the sarcolemma and laminin in the basal lamina, and in α7 transgenic mice it also decreases internal α7 chain

To test whether increasing the amount of β1 chain also promotes α7 chain and laminin localization at the sarcolemma in vivo, Ad-β1D adenovirus was also used to enhance expression of β1D chain in non-transgenic wild-type mice. Viruses have been widely used to deliver cDNAs into dystrophic skeletal muscle (60–62). The viruses were tittered and shown to promote expression of β1D in both NIH3T3 fibroblasts and C2C12 myoblasts (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3A). Immunofluorescence staining of serial sections of wild-type gastrocnemius muscles injected with Ad-β1D virus showed higher levels of β1D chain at the injection sites (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). Due to the high level of β1D chain in some infected fibers, internal staining of β1D was also observed (Fig. 4Aa). In contrast, in non-infected regions and in Ad-β-gal virus-injected muscle, the levels of β1D were not altered (Fig. 4Ad and g) confirming that higher β1D expression did not result from non-specific responses to virus. Consistent with our results in C2C12 cells, we observed a corresponding increase in the amount of α7 at the sarcolemma of fibers that had high levels of β1D chain (Fig. 4Ab), and this was not seen in non-infected regions (Fig. 4Ae and h) nor in muscle injected with Ad-β-gal virus (Fig. 4Ag and i). Similarly, in mdx mice injected with β1D viruses, increased amounts of α7 integrin were also detected at the sarcolemma in virus-infected areas compared with non-infected areas (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5A). Since more LAMA2 mRNA was detected in the C2C12 cells over-expressing β1D, we examined whether this increase of the integrin's ligand is also observed in vivo. Double staining of integrin β1D and laminin2/4 demonstrates increased laminin in the basal lamina around fibers infected with β1D virus (Fig. 4B). This increase of laminin2/4 was also detected in mdx mice injected with β1D virus (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5B). Thus, increasing β1D expression promotes more α7β1 integrin and laminin at the sarcolemma and enhances connections between muscle and its basal lamina.

Figure 4.

Ad-β1D virus increases sarcolemmal α7 integrin and laminin in wild-type mice. (A) Ad-β1D adenovirus (1 × 1010pfu) was injected into the gastrocnemius muscles of 5-day-old wild-type mice (n = 5). Immunofluorescence staining of serial sections was performed using anti-β1D antibody and antibody against the α7 chain. Contralateral legs were injected with Ad-β-gal virus. (a) High levels of β1D were detected in Ad-β1D virus-infected fibers compared with non-infected areas in the same section (d) or Ad-β-gal virus-infected muscle (g). α7 staining was also elevated in Ad-β1D virus-infected fibers (b) but not in non-infected fibers (e) or Ad-β-gal virus-infected fibers (h). Asterisk denotes same fibers in pairs of serial sections in (a and b), (d and e), (g, h and i). Bar = 100 µm. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of β1D integrin and laminin in wild-type mice injected with β1D adenovirus (n = 5). Levels of laminin correlate with the levels β1D in the infected muscle fibers. Bar = 50 µm.

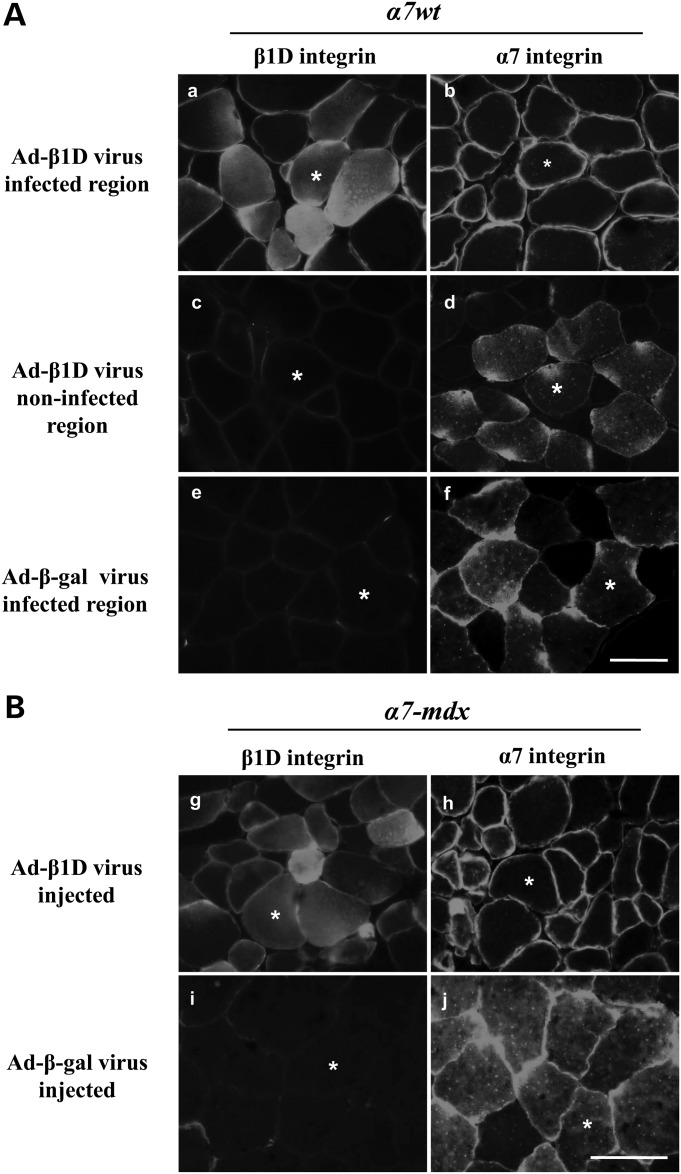

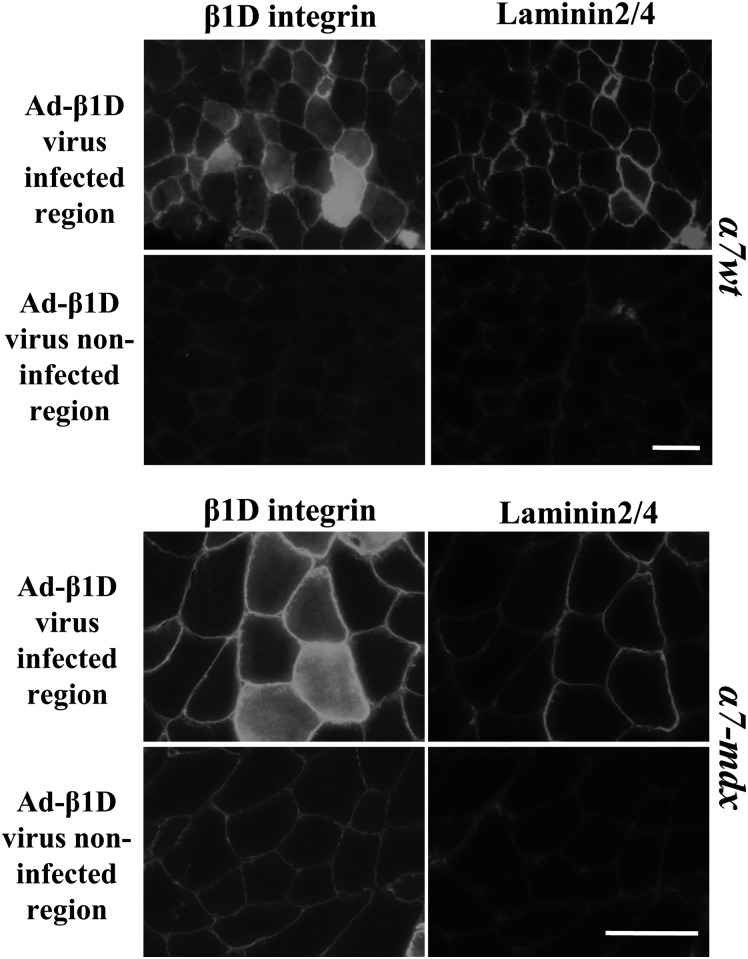

As described earlier, in skeletal muscle of transgenic mice expressing high levels of α7, integrin staining was detected inside myofibers (Fig. 2B). To confirm that β1D is the limiting factor underlying internal retention of α7 chain, Ad-β1D virus was injected into the gastrocnemius muscles of α7wt and α7-mdx mice. In both α7 transgenic wild-type and mdx mice, more β1D chain was detected in fibers injected with β1D virus (Fig. 5Aa and 5Bg), internal localization of α7 was diminished or totally absent and sarcolemmal staining of α7 was much brighter (Fig. 5Ab and 5Bh). In contrast, in regions of muscle in the same sections not infected with β1D virus, no increase of β1D was detected and internal staining of α7 remained abundant (Fig. 5Ac and 5Bd). In muscle injected with Ad-β-gal virus, internal staining of α7 chain was also still apparent (Fig. 5Af and 5Bj). We then examined whether increasing β1D in α7 transgenic wild-type and mdx mice promotes laminin–integrin connections at the sarcolemma. Staining of laminin2/4 and β1D integrin confirmed that there is also an increase of laminin around the β1D virus-infected muscle fibers of α7 integrin transgenic mice (Fig. 6). Therefore, we conclude that high levels of sarcolemma α7 integrin can be achieved by increasing the amount of β1D chain in both α7wt and α7-mdx mice and together the resulting α7β1D complex enhances integrin-basal lamina connections.

Figure 5.

Injection of β1D virus into α7 transgenic mice increased α7 integrin localization at the sarcolemma and reduced internal α7 chain. Immunofluorescence staining of serial sections of the gastrocnemius muscles from adenovirus injected (A) α7wt and (B) α7-mdx mice. Increased β1D was detected in β1D virus-infected fibers (a and g) compared with non-infected fibers (c and i) or β-galactosidase infected muscle fibers (e). Internal localization of α7, commonly seen in these transgenic mice was diminished in the β1D virus-infected fibers (b and h) but not in non-infected fibers (d and j) or β-galactosidase infected fibers (f). Asterisk denotes same fiber in pairs of serial sections in (a and b), (c and d), (e and f), (g and h) and (i and j). Six animals for each genotype. Bar = 50 µm.

Figure 6.

Injection of Ad-β1D virus increases laminin levels in α7 transgenic mice. Immunofluorescence staining of β1D integrin and laminin in α7wt and α7-mdx mice injected with β1D adenovirus. The increased levels of laminin coincide with the increased levels of β1D in the Ad-β1D virus-infected muscle fibers. Six animals for each genotype. Bar = 25 µm.

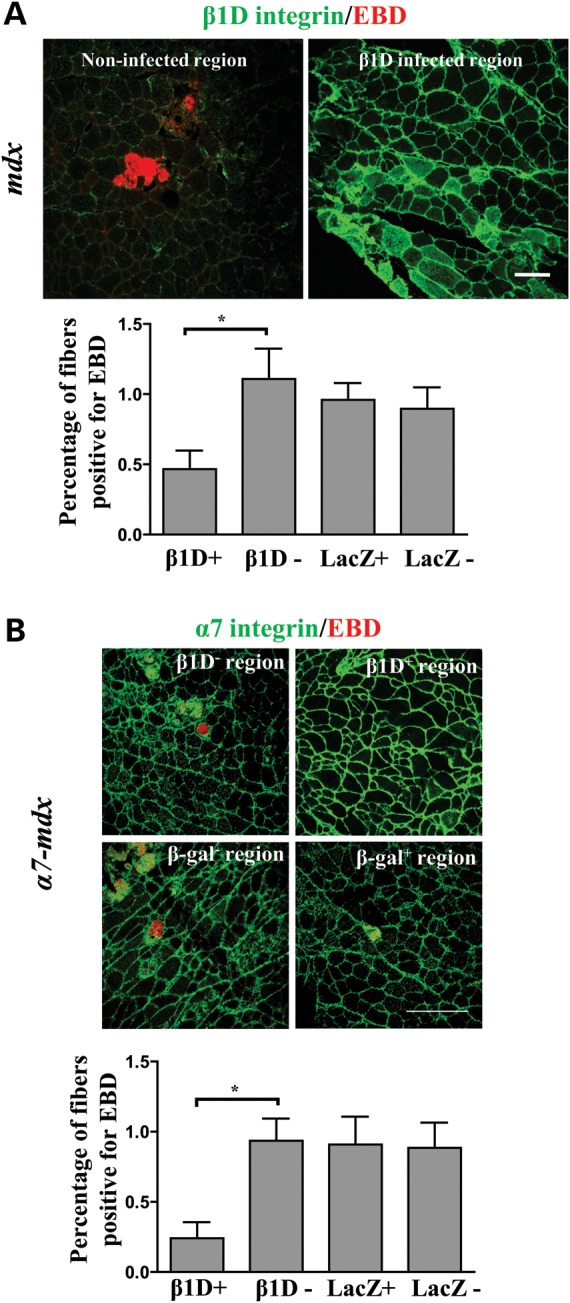

Increasing the amount of β1D chain protects against sarcolemma damage in mdx and α7 transgenic mdx mice

One of the hallmarks of dystrophic muscle is the compromised muscle fiber membrane that results from the diminished association of fibers with the extracellular matrix. Sarcolemmal damage is an indicator of degenerating muscle fibers and the uptake of EBD is commonly used to assess this damage (63). To determine whether the increased potential for integrin–laminin connections observed in the β1D virus-infected mice can protect against the development of muscle membrane damage, we quantified the EBD uptake in mdx and α7-mdx mice injected with β1D virus. Significantly fewer EBD-positive fibers were detected in the β1D virus-infected areas of the mdx mice than in non-infected areas (Fig. 7A). Similarly, virus-mediated enhancement of β1D levels also increased the amount of α7β1 in the sarcolemma and laminin in the basal membrane and reduced internal localization of α7 chain in α7-mdx mice. Increasing β1D levels also protected muscle fibers in α7-mdx mice from developing membrane damage (Fig. 7B). Quantification of EBD-positive fibers in Ad-β1D and Ad-β-gal virus-infected and non-infected muscle regions demonstrates a significant reduction of EBD-positive fibers in β1D virus-infected regions in both mdx and α7-mdx mice (Fig. 7). The protection afforded by simultaneously increasing β1D and α7 chains appears to be greater than that attained by solely increasing β1D chain as there were fewer β1D virus-infected fibers that were also EBD positive in α7-mdx mice compared with mdx mice. These results suggest that increasing β1D integrin levels in skeletal muscle promotes the formation of α7β1D complexes at the sarcolemma and this increase in membrane integrin promotes linkage of the muscle fiber with the extracellular matrix and protects against the development of membrane damage. These results also indicate that simultaneous enhancement of α7 and β1D chains may more effectively alleviate muscular dystrophy than increasing α7 chain alone. Finally, our results demonstrate the importance of balancing the levels of each component of the integrin focal adhesion complex if one is to develop an effective integrin-mediated therapy for muscular dystrophy.

Figure 7.

Increasing β1D chain increases α7β1 at the sarcolemma and protects membrane integrity in mdx and α7-mdx mice. (A) Sarcolemma integrity in virus-injected mdx mice (n = 5). Representative confocal images of muscle sections from adenovirus-injected mdx mice stained for β1D (green) and EBD (red). Bar = 100 µm. Quantification of EBD-positive fibers demonstrates protection of mdx muscle fibers from membrane damage in β1D virus-infected regions. This protection was not observed in non-infected regions or in β-galactosidase virus-infected regions. At least five sections from each animal were quantified; the data presented are from three animals. *P < 0.05. (B) Sarcolemma integrity in virus-injected α7-mdx mice (n = 5). Representative confocal images of β1D-infected (β1D+), β1D non-infected (β1D–), β-galactosidase-infected (β-galactosidase+) and β-galactosidase non-infected (β-galactosidase–) regions stained with anti-α7 antibody (green) and EBD (red). Bar = 250 µm. Quantification of the EBD-positive fibers demonstrates protection of α7-mdx muscle fiber from membrane damage by increasing β1D levels in these fibers. No muscle fibers expressing high levels of β1D showed the EBD uptake; the small percent of EBD-positive fibers are from non-infected fibers in the β1D virus-infected regions. At least five sections from each animal were quantified and data presented are from five animals. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

DMD is the most common X-linked hereditary human disease (1). It is characterized by progressive muscle degeneration, extensive inflammatory cell infiltration and large areas of fibrosis within skeletal muscle. Although more than two decades after mutations in the dystrophin gene were first identified as the primary defect causing DMD (64,65), there is still no cure or effective treatment for this disease. The mdx mouse has been the primary model used to study DMD pathogenesis and to explore potential therapies (46,66). In DMD patients, mutations in dystrophin result in a compromised association of the extracellular matrix with the muscle cytoskeleton and, subsequently, a severely weakened sarcolemma (3). Patients frequently develop cardiomyopathy, and usually die in their early 20s primarily from respiratory failure (67). In contrast, mdx mice also lack dystrophin, but they do not develop severe cardiomyopathy and have a relatively normal life span (68–70). More recently, mdx/utrn−/− mice, with a severe pathology more akin to DMD patients, have been developed and used to further test the effectiveness of various treatments for DMD (23,24).

Several therapeutic strategies have been shown to be effective in alleviating muscular dystrophy in these mouse models (1). These include stem cell base therapy, direct or compensatory gene therapy, anti-inflammation treatments, protease inhibitors, small molecule-based therapies (myostatin inhibitors, HDAC inhibitors, etc) and treatment with IGF. All have achieved certain levels of success in alleviating dystrophy (for review, see 1). Since both the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex and the α7β1 integrin are major laminin receptors in skeletal muscle, increasing α7β1 levels in dystrophic muscle represents another promising therapeutic method for treating Duchenne and other muscular dystrophies. We previously demonstrated that increasing the amount of α7 integrin chain in mdx/utrn−/− mice can partially alleviate muscular dystrophy and increase life span 3-fold by maintaining MTJ and NMJ structure, by preventing muscle fiber apoptosis, and by increasing the satellite cell pool and thereby promoting regeneration (21,22). However, solely increasing α7 protein in mdx mice did not yield apparent beneficial effects. Additionally, none of the lines of α7-mdx/utrn−/− mice generated had more than a 2-fold increase in α7 chain and this suggested that the expression and hence the benefit of enhancing α7 chain levels may be limited. A more detailed examination of those α7 transgenic wild-type and mdx mice revealed that some of the α7 chain was within muscle fibers and not at the sarcolemma where it is normally localized. This suggested that some factor may limit targeting of excess α7 integrin to the membrane and thereby limit its therapeutic effects. Microarray analysis has helped in identifying several such potential limiting factors (45). For example, the expression of genes encoding other components of focal adhesions was not increased when α7 levels were enhanced in the transgenic mice (45). Similarly, immunofluorescence staining demonstrated no corresponding increase of β1 integrin chain in the α7 transgenic wild-type and mdx mice. Moreover, western blots confirmed that in α7 integrin transgenic mice the total amount of β1 protein was slightly decreased and the pre-matured form of β1 chain was specifically depleted. These observations suggested that insufficient β1 chain may limit targeting of the α7β1 integrin to the muscle membrane. In support of this, over-expressing β1D integrin chain in C2C12 cells led to more α7 integrin and LAMA2 transcripts and their corresponding proteins at the myotube surface. Thus the amount of β1D integrin is important for membrane localization of the heterodimers and it may also regulate alpha chain and laminin gene expression.

To test this hypothesis in vivo adenovirus containing β1D cDNA was injected into α7 transgenic wild-type, α7 transgenic mdx mice, and their non-transgenic controls. In wild-type mice, injection of β1D virus resulted in muscle fibers with elevated levels of β1D. In some cases, internal staining of excess β1D was detected confirming that adenovirus-mediated expression can sustain high levels of β1D synthesis for at least 4 weeks after injection. Immunostaining of serial sections demonstrated higher levels of α7 at the sarcolemma of fibers infected with β1D virus compared with non-infected fibers in wild-type mice. Thus, increasing the amount of β1D can result in the localization of more α7β1 integrin at the sarcolemma and promote integrin function. Normally, cells synthesize α and β chains in specific ratios and excess non-dimerized chain is retained in the ER (40,42). When β1D expression was increased by virus, more β1D subunits were available to dimerize with α7 chain and the α7β1D complex was targeted to the sarcolemma. The increased detection of laminin in basal lamina and integrin at the sarcolemma of wild-type muscle injected with β1D virus is encouraging and suggests that increasing β1D levels in muscular dystrophy may also effectively alleviate the development of pathology. Our results indicate that the expression of both integrin and its substrate laminin are coordinately regulated and this conclusion is supported by the recent report that laminin111 administration into mice increased α7β1 at the sarcolemma and inhibited development of muscular dystrophy (71).

Over-expression of β1D in α7wt and α7-mdx transgenic mice also reduced internal localization of α7 chain, confirming that in the α7 transgenic mice, insufficient β1D chain was at least one of the factors limiting the targeting of α7 to the cell membrane. Increasing β1D in these fibers resulted in more α7β1D integrin at the membrane and more of its ligand, laminin, in the basal lamina around these muscle fibers. This enhancement of trans-sarcolemmal linkages results in better integrin-mediated compensation for defects in the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex. In the absence of dystrophin, membrane integrity in mdx muscle fibers is compromised. As a result, muscle fibers become damaged and permeable to interstitial fluid that contains albumin. This can be visualized microscopically by EBD–albumin complexes in those fibers. As shown in this study, increasing β1D in mdx and in α7 transgenic mdx mice effectively prevents sarcolemmal damage. Moreover, it appears that increasing the amount of both the α7 and β1 integrin subunits together can alleviate muscular dystrophy in mdx mice that cannot be achieved by solely increasing the amount of α7 chain. Similarly, other components of focal adhesions may need to be optimized to achieve the maximum beneficial effects of increasing integrin in skeletal muscle as an effective therapy for muscular dystrophy. In this regard, it is encouraging to note that increasing β1D levels enhances expression of both α7 and laminin genes and protein. Functional and physiological studies in transgenic animal are needed to definitively demonstrate the therapeutic potential of increasing integrin β1D or integrin α7 and β1D together.

In summary, increasing the amount of functional α7β1D complex has the potential to alleviate muscular dystrophy. Virus-mediated β1D expression in mdx and α7 transgenic mdx mice demonstrates that simultaneously increasing α7 and β1D in mdx mice may better alleviate dystrophy compared with solely increasing the amount of α7 chain. Together, these results support enhancement of α7β1 integrin as a therapy for muscular dystrophy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Mice used in this study include α7 integrin transgenic wild-type (α7wt) and α7 integrin transgenic mdx (α7-mdx) and mdx/utrn−/− (α7-mdx/utrn−/−) mice. Corresponding non-transgenic mice (wt, mdx and mdx/utrn−/−) were also used. Animals were housed and handled according to guidelines of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institutes of Health. Genotyping was performed as previously described (11,21,22,45).

Cell culture

AD293 cells and NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were maintained at 37°C, in 5% CO2, in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 4500 mg/l d-glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were infected with integrin β1D and β-galactosidase virus at 25 plaque-forming units (PFU)/cell. C2C12 mouse myoblasts were maintained as described previously (21). Transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's instructions. After transfection, C2C12 cells were switched to differentiation medium (DMEM, containing 2% horse serum) to induce myotube formation for 3 days.

Plasmids, primers and viral vectors

The adenovirus containing human integrin β1D cDNA used in these experiments was previously reported (59). A virus vector containing cDNA of β-galactosidase driven by CMV was used as a control. Integrin β1D cDNA was PCR amplified and cloned under the α-MHCK promote amplified from α-MHCKChCAT plasmid (a gift from Dr. Stephen Hauschka, University of Washington). Primers: forward primer: ATGCGGCCGCGTAATCATGGTCATAGCTGTTTCCT; reverse primer: TAGAATTCGCTGGCTGGCTCCTGAGT. Primers used in the real time PCR are as following: ITGA7: forward primer: GGCTGGGCTGTTAGTCCTG; reverse primer: ATGGGCTCGGTGATAGTTGGT; ITGB1: forward primer: ATGCCAAATCTTGCGGAGAAT; reverse primer: TTTGCTGCGATTGGTGACATT; LAMA2: forward primer: TCCCAAGCGCATCAACAGAG; reverse primer: CAGTACATCTCGGGTCCTTTTTC; LAMB1: forward primer: CTTAAGGAGGGAGCGAACCT; reverse primer: AAGCTCCAGCTGTTGGAAGA.

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibody against α7 integrin cytoplasmic domain B was used to detect both endogenous and transgenic α7 chain. Rabbit polyclonal antibody against integrin β1D was provided by Dr W. K. Song (Kwang-ju Institute of Technology). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against total β1 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit polyclonal antibody and mouse monoclonal antibody against calnexin, obtained from Stressmarq Biosciences and BD bioscience respectively, was used as an ER marker. Monoclonal antibody against laminin2/4 is a generous gift from Dr William D. Matthews (Duke University). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled wheat germ agglutinin (FITC-WGA) was obtained from Invitrogen. Fluorescein and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled donkey anti-mouse or rabbit secondary antibody were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory.

Histology

Ten micrometer cryostat sections of gastrocnemius muscle were fixed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin as described previously (45). For EBD quantification, mdx and α7-mdx mice were injected intraperitoneally with 10 mg/ml EBD at 0.1 ml per 10 g of bodyweight. To delineate muscle fibers, tissue sections were stained with either FITC-WGA (Invitrogen) diluted 1:1000 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min or with anti-α7 integrin antibody.

Western blots

Muscle tissues were powdered in liquid nitrogen. Proteins were extracted with 200 mm octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside in 50 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1:200 dilution of Protease Cocktail Set III (Calbiochem), 1 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm MgCl2 at 4°C, for 30 min. Supernatants were collected after centrifugation at 16 000g for 5 min at 4°C and protein concentrations were determined using Bradford assays (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of proteins were separated on 8% polyacrylamide-sodium dodecyl sulfate gels electrophoresed at 40 mA for 1 h. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for 1 h at 100 V. To ensure equal loading, after transfer the membranes were stained with Ponceau S (Sigma). Blocked membranes were incubated with primary antibodies in 2% non-fat milk for 1 h. HRP-linked secondary antibodies were used to detect bound primary antibodies. Immunoreactive protein bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham). Band intensities were quantified with ImageQuant software (Amersham).

Intramuscular injection of adenovirus

AD293 virus packaging cells were used to prepare concentrated virus and virus titer was determined as plaque-forming units per milliliter. 1 × 1010 PFU of β1D virus (in 10 μl saline) were injected into one of the gastrocnemius of 5 day old pups and same PFU of β-galactosidase virus were injected into the contralateral legs. Four weeks after injection, gastrocnemius muscles were dissected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane. For assessing muscle damage in virus-injected mice, sections were incubated with 0.001% of EBD for 5 min and then extensively rinsed with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS to visualize the EBD-positive muscle fibers as described previously (72).

Immunofluorescence and microcopy

C2C12 cells were fixed with 4% para-formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. α7 integrin chain was detected by immunofluorescence using 20 µg/ml mouse monoclonal antibody (O26) raised against rat α7. β1D integrin chain was detected using a rabbit polyclonal antibody. Virus-infected culture cells were stained first for surface α7 using monoclonal antibody (O26) and then fixed in ice-cold acetone for 1 min, rehydrated in PBS for 30 min, blocked with 5% BSA in PBS for 1 h at 4°C, and incubated sequentially with 1:500 primary anti-β1D antibody and secondary antibody for 1 h each. Coverslips were mounted using Vectorshield (Vector Laboratories). To detect α7 and β1D in muscle, sections were fixed in −20°C acetone for 1 min, rehydrated in PBS for 10 min and blocked in PBS containing 10% horse serum for 30 min. Rabbit polyclonal primary antibodies in PBS containing 1% horse serum were then applied for 1 h followed by extensive washing. Secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h. For negative controls, primary antibodies were omitted. Immunofluorescence images were acquired using a Leica DMRXA2 microscope equipped with an AxioCam digital camera (Carl Zeiss) and analyzed with Openlab software (Improvision). Confocal images were obtained using a Leica TCS SP2 RBB SP-2 laser scanning confocal microscope.

Statistics

All quantification data are represented as mean ± SEM. Two group comparisons were performed using unpaired Student's t-test. Differences were consider significant if P < 0.05.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-AG014632 to S.J.K., and PO1 HL46345, RO1 HL088390 and RO1 HL103566 to R.S.R.) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (to S.J.K., J.L. and D.J.M.). J.L. is also supported by an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Woo Keun Song for providing the anti-β1D integrin antibody, Dr William D. Matthew (Duke University) for the anti-laminin antibody and Dr. Stephen D. Hauschka (University of Washington) for the α-MHCKChCAT plasmid. We also thank Dr Stephen A. Boppart and the Beckman Institute Imaging Technology Group (ITG) for assistance with the confocal microscope.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davies K.E., Nowak K.J. Molecular mechanisms of muscular dystrophies: old and new players. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:762–773. doi: 10.1038/nrm2024. doi:10.1038/nrm2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsumura K., Ohlendieck K., Ionasescu V.V., Tome F.M., Nonaka I., Burghes A.H., Mora M., Kaplan J.C., Fardeau M., Campbell K.P. The role of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex in the molecular pathogenesis of muscular dystrophies. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1993;3:533–535. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(93)90110-6. doi:10.1016/0960-8966(93)90110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell K.P., Kahl S.D. Association of dystrophin and an integral membrane glycoprotein. Nature. 1989;338:259–262. doi: 10.1038/338259a0. doi:10.1038/338259a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blake D.J., Weir A., Newey S.E., Davies K.E. Function and genetics of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins in muscle. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:291–329. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von der Mark H., Durr J., Sonnenberg A., von der Mark K., Deutzmann R., Goodman S.L. Skeletal myoblasts utilize a novel beta 1-series integrin and not alpha 6 beta 1 for binding to the E8 and T8 fragments of laminin. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:23593–23601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song W.K., Wang W., Foster R.F., Bielser D.A., Kaufman S.J. H36-alpha 7 is a novel integrin alpha chain that is developmentally regulated during skeletal myogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 1992;117:643–657. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.3.643. doi:10.1083/jcb.117.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkin D.J., Kaufman S.J. The alpha7beta1 integrin in muscle development and disease. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;296:183–190. doi: 10.1007/s004410051279. doi:10.1007/s004410051279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song W.K., Wang W., Sato H., Bielser D.A., Kaufman S.J. Expression of alpha 7 integrin cytoplasmic domains during skeletal muscle development: alternate forms, conformational change, and homologies with serine/threonine kinases and tyrosine phosphatases. J. Cell Sci. 1993;106(Pt 4):1139–1152. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.4.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crawley S., Farrell E.M., Wang W., Gu M., Huang H.Y., Huynh V., Hodges B.L., Cooper D.N., Kaufman S.J. The alpha7beta1 integrin mediates adhesion and migration of skeletal myoblasts on laminin. Exp. Cell Res. 1997;235:274–286. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3671. doi:10.1006/excr.1997.3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bao Z.Z., Lakonishok M., Kaufman S., Horwitz A.F. Alpha 7 beta 1 integrin is a component of the myotendinous junction on skeletal muscle. J. Cell Sci. 1993;106(Pt 2):579–589. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.2.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boppart M.D., Burkin D.J., Kaufman S.J. Alpha7beta1-integrin regulates mechanotransduction and prevents skeletal muscle injury. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1660–C1665. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00317.2005. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00317.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin P.T., Kaufman S.J., Kramer R.H., Sanes J.R. Synaptic integrins in developing, adult, and mutant muscle: selective association of alpha1, alpha7A, and alpha7B integrins with the neuromuscular junction. Dev. Biol. 1996;174:125–139. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0057. doi:10.1006/dbio.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boppart M.D., Volker S.E., Alexander N., Burkin D.J., Kaufman S.J. Exercise promotes alpha7 integrin gene transcription and protection of skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2008;295:R1623–R1630. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00089.2008. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00089.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi Y.K., Chou F.L., Engvall E., Ogawa M., Matsuda C., Hirabayashi S., Yokochi K., Ziober B.L., Kramer R.H., Kaufman S.J., et al. Mutations in the integrin alpha7 gene cause congenital myopathy. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:94–97. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-94. doi:10.1038/ng0598-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer U., Saher G., Fassler R., Bornemann A., Echtermeyer F., von der Mark H., Miosge N., Poschl E., von der Mark K. Absence of integrin alpha 7 causes a novel form of muscular dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:318–323. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-318. doi:10.1038/ng1197-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flintoff-Dye N.L., Welser J., Rooney J., Scowen P., Tamowski S., Hatton W., Burkin D.J. Role for the alpha7beta1 integrin in vascular development and integrity. Dev. Dyn. 2005;234:11–21. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20462. doi:10.1002/dvdy.20462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pegoraro E., Cepollaro F., Prandini P., Marin A., Fanin M., Trevisan C.P., El-Messlemani A.H., Tarone G., Engvall E., Hoffman E.P., et al. Integrin alpha 7 beta 1 in muscular dystrophy/myopathy of unknown etiology. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;160:2135–2143. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61162-5. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61162-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peat R.A., Smith J.M., Compton A.G., Baker N.L., Pace R.A., Burkin D.J., Kaufman S.J., Lamande S.R., North K.N. Diagnosis and etiology of congenital muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2008;71:312–321. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000284605.27654.5a. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000284605.27654.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vachon P.H., Xu H., Liu L., Loechel F., Hayashi Y., Arahata K., Reed J.C., Wewer U.M., Engvall E. Integrins (alpha7beta1) in muscle function and survival. Disrupted expression in merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:1870–1881. doi: 10.1172/JCI119716. doi:10.1172/JCI119716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodges B.L., Hayashi Y.K., Nonaka I., Wang W., Arahata K., Kaufman S.J. Altered expression of the alpha7beta1 integrin in human and murine muscular dystrophies. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 22):2873–2881. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.22.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burkin D.J., Wallace G.Q., Nicol K.J., Kaufman D.J., Kaufman S.J. Enhanced expression of the alpha 7 beta 1 integrin reduces muscular dystrophy and restores viability in dystrophic mice. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:1207–1218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1207. doi:10.1083/jcb.152.6.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkin D.J., Wallace G.Q., Milner D.J., Chaney E.J., Mulligan J.A., Kaufman S.J. Transgenic expression of {alpha}7{beta}1 integrin maintains muscle integrity, increases regenerative capacity, promotes hypertrophy, and reduces cardiomyopathy in dystrophic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;166:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62249-3. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62249-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grady R.M., Teng H., Nichol M.C., Cunningham J.C., Wilkinson R.S., Sanes J.R. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90:729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80533-4. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deconinck A.E., Rafael J.A., Skinner J.A., Brown S.C., Potter A.C., Metzinger L., Watt D.J., Dickson J.G., Tinsley J.M., Davies K.E. Utrophin-dystrophin-deficient mice as a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80532-2. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rooney J.E., Welser J.V., Dechert M.A., Flintoff-Dye N.L., Kaufman S.J., Burkin D.J. Severe muscular dystrophy in mice that lack dystrophin and alpha7 integrin. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:2185–2195. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02952. doi:10.1242/jcs.02952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo C., Willem M., Werner A., Raivich G., Emerson M., Neyses L., Mayer U. Absence of alpha 7 integrin in dystrophin-deficient mice causes a myopathy similar to Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:989–998. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl018. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allikian M.J., Hack A.A., Mewborn S., Mayer U., McNally E.M. Genetic compensation for sarcoglycan loss by integrin alpha7beta1 in muscle. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:3821–3830. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01234. doi:10.1242/jcs.01234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziober B.L., Vu M.P., Waleh N., Crawford J., Lin C.S., Kramer R.H. Alternative extracellular and cytoplasmic domains of the integrin alpha 7 subunit are differentially expressed during development. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:26773–26783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vignier N., Moghadaszadeh B., Gary F., Beckmann J., Mayer U., Guicheney P. Structure, genetic localization, and identification of the cardiac and skeletal muscle transcripts of the human integrin alpha7 gene (ITGA7) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;260:357–364. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0916. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collo G., Starr L., Quaranta V. A new isoform of the laminin receptor integrin alpha 7 beta 1 is developmentally regulated in skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:19019–19024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chernousov M.A., Kaufman S.J., Stahl R.C., Rothblum K., Carey D.J. Alpha7beta1 integrin is a receptor for laminin-2 on Schwann cells. Glia. 2007;55:1134–1144. doi: 10.1002/glia.20536. doi:10.1002/glia.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armulik A. Splice variants of human beta 1 integrins: origin, biosynthesis and functions. Front. Biosci. 2002;7:d219–d227. doi: 10.2741/A721. doi:10.2741/armulik. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Melker A.A., Sonnenberg A. Integrins: alternative splicing as a mechanism to regulate ligand binding and integrin signaling events. Bioessays. 1999;21:499–509. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199906)21:6<499::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-D. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199906)21:6<499::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brakebusch C., Hirsch E., Potocnik A., Fassler R. Genetic analysis of beta1 integrin function: confirmed, new and revised roles for a crucial family of cell adhesion molecules. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 23):2895–2904. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.23.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belkin A.M., Retta S.F., Pletjushkina O.Y., Balzac F., Silengo L., Fassler R., Koteliansky V.E., Burridge K., Tarone G. Muscle beta1D integrin reinforces the cytoskeleton-matrix link: modulation of integrin adhesive function by alternative splicing. J. Cell Biol. 1997;139:1583–1595. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.6.1583. doi:10.1083/jcb.139.6.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belkin A.M., Zhidkova N.I., Balzac F., Altruda F., Tomatis D., Maier A., Tarone G., Koteliansky V.E., Burridge K. Beta 1D integrin displaces the beta 1A isoform in striated muscles: localization at junctional structures and signaling potential in nonmuscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 1996;132:211–226. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.1.211. doi:10.1083/jcb.132.1.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baudoin C., Goumans M.J., Mummery C., Sonnenberg A. Knockout and knockin of the beta1 exon D define distinct roles for integrin splice variants in heart function and embryonic development. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1202–1216. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.8.1202. doi:10.1101/gad.12.8.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stephens L.E., Sutherland A.E., Klimanskaya I.V., Andrieux A., Meneses J., Pedersen R.A., Damsky C.H. Deletion of beta 1 integrins in mice results in inner cell mass failure and peri-implantation lethality. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1883–1895. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1883. doi:10.1101/gad.9.15.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hynes R.O. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heino J., Ignotz R.A., Hemler M.E., Crouse C., Massague J. Regulation of cell adhesion receptors by transforming growth factor-beta. Concomitant regulation of integrins that share a common beta 1 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:380–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ignotz R.A., Heino J., Massague J. Regulation of cell adhesion receptors by transforming growth factor-beta. Regulation of vitronectin receptor and LFA-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lenter M., Vestweber D. The integrin chains beta 1 and alpha 6 associate with the chaperone calnexin prior to integrin assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:12263–12268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salicioni A.M., Gaultier A., Brownlee C., Cheezum M.K., Gonias S.L. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 promotes beta1 integrin maturation and transport to the cell surface. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:10005–10012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306625200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M306625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milner D.J., Kaufman S.J. α7β1 integrin does not alleviate disease in a mouse model of limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2F. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;170:609–619. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060686. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2007.060686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu J., Burkin D.J., Kaufman S.J. Increasing α7β1-integrin promotes muscle cell proliferation, adhesion, and resistance to apoptosis without changing gene expression. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C627–C640. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00329.2007. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00329.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bulfield G., Siller W.G., Wight P.A., Moore K.J. X chromosome-linked muscular dystrophy (mdx) in the mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:1189–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.4.1189. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.4.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bellet M., Whalen J.J., Bodin F., Serrurier D., Tanner K., Menard J. Use of crossover trials to obtain antihypertensive dose–response curves and to study combination therapy during the development of benazepril. J. Hypertens. Suppl. 1990;8:S43–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carlson B.M., Faulkner J.A. The regeneration of skeletal muscle fibers following injury: a review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1983;15:187–198. doi:10.1249/00005768-198315030-00002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DiMario J.X., Uzman A., Strohman R.C. Fiber regeneration is not persistent in dystrophic (MDX) mouse skeletal muscle. Dev. Biol. 1991;148:314–321. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90340-9. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(91)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karpati G., Carpenter S., Prescott S. Small-caliber skeletal muscle fibers do not suffer necrosis in mdx mouse dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11:795–803. doi: 10.1002/mus.880110802. doi:10.1002/mus.880110802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Webster C., Silberstein L., Hays A.P., Blau H.M. Fast muscle fibers are preferentially affected in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1988;52:503–513. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90463-1. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90463-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whalen R.G., Harris J.B., Butler-Browne G.S., Sesodia S. Expression of myosin isoforms during notexin-induced regeneration of rat soleus muscles. Dev. Biol. 1990;141:24–40. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90099-5. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(90)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajagopalan S., Xu Y., Brenner M.B. Retention of unassembled components of integral membrane proteins by calnexin. Science. 1994;263:387–390. doi: 10.1126/science.8278814. doi:10.1126/science.8278814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen Y.W., Zhao P., Borup R., Hoffman E.P. Expression profiling in the muscular dystrophies: identification of novel aspects of molecular pathophysiology. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:1321–1336. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1321. doi:10.1083/jcb.151.6.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bakay M., Zhao P., Chen J., Hoffman E.P. A web-accessible complete transcriptome of normal human and DMD muscle. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2002;12(Suppl. 1):S125–S141. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(02)00093-7. doi:10.1016/S0960-8966(02)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cachaco A.S., Chuva de Sousa Lopes S.M., Kuikman I., Bajanca F., Abe K., Baudoin C., Sonnenberg A., Mummery C.L., Thorsteinsdottir S. Knock-in of integrin beta 1D affects primary but not secondary myogenesis in mice. Development. 2003;130:1659–1671. doi: 10.1242/dev.00394. doi:10.1242/dev.00394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burkin D.J., Gu M., Hodges B.L., Campanelli J.T., Kaufman S.J. A functional role for specific spliced variants of the alpha7beta1 integrin in acetylcholine receptor clustering. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:1067–1075. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.1067. doi:10.1083/jcb.143.4.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burkin D.J., Kim J.E., Gu M., Kaufman S.J. Laminin and alpha7beta1 integrin regulate agrin-induced clustering of acetylcholine receptors. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 16):2877–2886. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.16.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pham C.G., Harpf A.E., Keller R.S., Vu H.T., Shai S.Y., Loftus J.C., Ross R.S. Striated muscle-specific beta(1D)-integrin and FAK are involved in cardiac myocyte hypertrophic response pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000;279:H2916–H2926. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Odom G.L., Gregorevic P., Chamberlain J.S. Viral-mediated gene therapy for the muscular dystrophies: successes, limitations and recent advances. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1772:243–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Judge L.M., Chamberlain J.S. Gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: AAV leads the way. Acta Myol. 2005;24:184–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duan D. Challenges and opportunities in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy gene therapy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15(Suppl. 2):R253–R261. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl180. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matsuda R., Nishikawa A., Tanaka H. Visualization of dystrophic muscle fibers in mdx mouse by vital staining with Evans blue: evidence of apoptosis in dystrophin-deficient muscle. J. Biochem. 1995;118:959–964. doi: 10.1093/jb/118.5.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoffman E.P., Brown R.H., Jr, Kunkel L.M. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987;51:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koenig M., Hoffman E.P., Bertelson C.J., Monaco A.P., Feener C., Kunkel L.M. Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell. 1987;50:509–517. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90504-6. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Allamand V., Campbell K.P. Animal models for muscular dystrophy: valuable tools for the development of therapies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:2459–2467. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.16.2459. doi:10.1093/hmg/9.16.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boland B.J., Silbert P.L., Groover R.V., Wollan P.C., Silverstein M.D. Skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle failure in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr. Neurol. 1996;14:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(95)00251-0. doi:10.1016/0887-8994(95)00251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lefaucheur J.P., Pastoret C., Sebille A. Phenotype of dystrophinopathy in old mdx mice. Anat. Rec. 1995;242:70–76. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092420109. doi:10.1002/ar.1092420109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pastoret C., Sebille A. Further aspects of muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1993;3:471–475. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(93)90099-6. doi:10.1016/0960-8966(93)90099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Torres L.F., Duchen L.W. The mutant mdx: inherited myopathy in the mouse. Morphological studies of nerves, muscles and end-plates. Brain. 1987;110(Pt 2):269–299. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.2.269. doi:10.1093/brain/110.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rooney J.E., Gurpur P.B., Burkin D.J. Laminin-111 protein therapy prevents muscle disease in the mdx mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:7991–7996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811599106. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811599106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berry S.E., Liu J., Chaney E.J., Kaufman S.J. Multipotential mesoangioblast stem cell therapy in the mdx/utrn−/− mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Regen. Med. 2007;2:275–288. doi: 10.2217/17460751.2.3.275. doi:10.2217/17460751.2.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu J., Gurpur P.B., Kaufman S.J. Genetically determined proteolytic cleavage modulates alpha7beta1 integrin function. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:35668–35678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804661200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M804661200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.