Abstract

When locomoting in a physically challenging environment, the body draws upon available energy reserves to accommodate increased metabolic demand. Ingested glucose supplements the body’s energy resources, whereas non-caloric sweetener does not. Two experiments demonstrate that participants who had consumed a glucose-containing drink perceived a hills slant to be less steep than did participants who had consumed a drink containing non-caloric sweetener. The glucose manipulation influenced participants’ explicit awareness of hill slant but, as predicted, it did not affect a visually-guided action of orienting a tilting palmboard to be parallel to the hill. Measured individual differences in factors related to bioenergetic state such as fatigue, sleep quality, fitness, mood, and stress also affected perception such that lower energetic states were associated with steeper perceptions of hill slant. This research shows that the perception of the environment’s spatial layout is influenced by the energetic resources available for locomotion within it. Our findings are consistent with the view that spatial perceptions are influenced by bioenergetic factors.

Keywords: Hill Perception, Slant Perception, Visual Perception, Space Perception, Glucose, Sugar, Economy of Action, Bioenergetics

Everyday experience suggests that the phenomenal world reflects the geometrical properties of our environment. That is, people assume that their perceptions are accurate and reliable representations of the physical world around them. In contrast, a view of perception based on an economy of action (Proffitt, 2006) proposes that visual perception is malleable and that people perceive the geometry of spatial layout in relation to the bioenergetic cost of acting on the environment and the current bioenergetic state of their bodies. For example, after having exercised heavily, people perceive hills as steeper than when they are not fatigued (Proffitt, Bhalla, Gossweiler, & Midgett, 1995). Similarly, people wearing heavy backpacks perceive hills to be steeper than do perceivers who are unencumbered (Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999). Such studies have demonstrated a relationship between spatial perception and factors that affect energy expenditure: Because a hill would be harder to climb for fatigued or encumbered people, they perceive it be to steeper1. Thus, perception of the physical world is not simply a function of optically specified objective features of the environment such as slant or extent, but is constrained by the perceiver’s capacity to act on that given space, at a given time.

The economy of action account proposes that spatial perceptions are scaled by the amount of energy required to perform actions relative to the amount of energy that is currently available. For example, perceived hill steepness is scaled by the amount of energy required to ascend the incline relative to the amount of available metabolic energy. Underlying this account is the assumption that the metabolic energy available to perform physical actions fluctuates depending on such factors as (1) inherent individual differences, (2) how much energy has been recently consumed in the form of food and drink, and (3) how much energy has been expended in the form of physical activity. For example, strenuous exercise depletes the body’s available energy in the form of circulating glucose, thereby making less glucose immediately available for future actions. This reduction in energy reserves has been postulated as the reason for why people perceived hills to be steeper when they are fatigued relative to when they are well rested (Proffitt, et al., 1995). This theoretical inference, however, is indirect, because the physical substrates implied by the notion of “energy reserves” have never been experimentally manipulated or measured. Furthermore, being aware of the experimental manipulation, participants might have concluded they were “supposed to” find the hill steeper because they were wearing a backpack or were fatigued, though this could not have been the case for effects driven by individual differences such as fitness and health as demonstrated in Bhalla and Proffitt (1999).

The two experiments reported in this paper pursued three aims: First, by manipulating metabolic energy we directly tested whether people’s energetic state influences their spatial perception. Second, the studies employed manipulations of metabolic energy in a non-obvious manner such that participants were completely unaware of whether they were in the high energy or low energy condition. If differences in perception were to be obtained, it would further support the proposition that these effects, and similar effects reported in earlier papers (e.g., Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999; Proffitt, et al., 1995; Schnall, Harber, Stefanucci, & Proffitt, 2008), were not the result of experimental demand characteristics. Third, assessing individual bioenergetic differences permitted an assessment of bioenergetic state on perceived slant, independent of any experimental manipulations.

Both experiments varied blood glucose levels, with the expectation that high blood glucose would make hills appear less steep. Two lines of research have investigated the role of blood glucose in the following contexts: First, glucose has distinct physiological effects on the body, and second, glucose levels can influence cognitive functioning. These research findings will be reviewed in turn.

Glucose and Physiology

At a fundamental level, all organisms are living energy systems in which every cell requires energy to sustain its functions. Two broad categories of energy expenditure can be distinguished: energy expenditure at rest and energy expenditure during physical activity. A minimum amount of energy is required to maintain bodily functions such as respiration, digestion, blood circulation and a host of everyday cellular activities. The amount of energy used by such necessary functions is set and relatively unchangeable. In contrast, the amount of energy used for physical activity is largely under voluntary control and can vary greatly depending on the choice of action performed in a given environment.

Whenever energy is used, it must be replaced. As omnivores, humans ingest nutrients in three basic forms: carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids. Although proteins and lipids have important roles in maintaining the structural and functional integrity of cells, neither is readily converted into an immediately available energy source. Carbohydrates, in contrast, serve almost exclusively to supply energy and can do so as soon as the demand arises. When consumed, carbohydrates are broken down into glucose, which enters the bloodstream and raises blood glucose levels. If energy is needed immediately it can be taken directly from the blood stream. In contrast, if energy supplies are already adequate, the increased blood glucose will be stored in the form of glycogen in the liver or muscles (Coyle, 2004; Coyle, Coggan, Hemmert, & Ivy, 1986).

Glucose carried in the blood, and stored in the muscles and liver as glycogen, is the primary fuel for muscle contraction and other cellular work, and is the only fuel usable by the brain. Although homeostatic mechanisms attempt to maintain blood glucose at a fairly constant level, fluctuations above and below normal occur on a regular basis and have meaningful physiological consequences (Peters, et al., 2004). At low levels of blood glucose, glycogen stores are tapped to return blood glucose to a normal level to ensure adequate fuel for the brain, but the result is that less fuel is in reserve for physical activity. Once the stored glycogen has been depleted, the brain and active muscles continue to use what little glucose remains in the blood, causing blood glucose levels to drop. As the body enters a hypoglycaemic state, physical performance is impaired. For example, when glucose supplies are depleted following prolonged physical activity, exercise power output is reduced and athletes experience exhaustion (Coyle, 2004; Murray, et al., 1987; Murray, Paul, Seifert, Eddy, & Halaby, 1989). If levels continue to fall beyond a critical point, as can occur in certain disease populations such as patients with diabetes mellitus, unconsciousness will result, followed by brain damage, coma, and eventually death (Benton, Parker, & Donohoe, 1996).

On the other hand, increased blood glucose levels may indicate to the brain a state of energy surplus or recent addition of energy to the system. With regard to physical activity, elevated blood glucose levels entail a benefit because if energy is required for physical activity at that moment, a large proportion can be derived from glucose in the blood, thereby sparing glycogen stores in the muscle tissue. Indeed, the field of exercise physiology has established that physical performance is enhanced with carbohydrate supplementation before and during exercise. Participants given carbohydrate supplements show increased power output over extended durations and increased time to exhaustion under intense exercise conditions (Achten, et al., 2004; Coyle, 2004; Coyle, et al., 1986; Davis, Jackson, Broadwell, Queary, & Lambert, 1997; Utter, et al., 2004; Welsh, Davis, Burke, & Williams, 2002).

Any physical action requires energy, but the amount of energy required varies depending on the properties of the environment in which the action takes place. For instance, walking up a 20° hill requires more energy than walking up a 5° hill. Similarly, walking up a hill while carrying a heavy backpack requires more energy than when unencumbered. In order to make energy-economical decisions about action choices, information about the energetic cost of potential actions must be acquired. Thus, it would be highly adaptive to have a mechanism available that indicates whether exerting a certain amount of energy is worthwhile, given the potential energetic costs and current energy stores. Proffitt (2006) proposed that visual perception constitutes such a mechanism: Opportunities for action are related to their energetic costs, and people are directly (though unconsciously) informed about these contingencies through their visual perception, because it reflects whether given the current state of the body, how costly it would be to perform a given action in the environment. If the energetic requirements for an action are high or the available energy is low, then hills will appear steeper than they would otherwise, thereby discouraging an individual from performing energetically costly actions. By this account, the study of bioenergetics the flow and transformation of energy in and between living organisms and between living organisms and their environment is integral to the study of the perception of spatial layout.

Glucose and Enhanced Cognitive Functioning

In addition to being available in the body for uptake by the muscles and other organs, glucose is also available in the brain. Indeed, a sizable body of research has established that glucose levels critically influence cognitive processes. Compared to low levels of glucose, optimally high levels of glucose have been associated with better memory performance in rodents (Gold, 1986; McNay, McCarty, & Gold, 2001; Messier & White, 1987; Ragozzino, Unick, & Gold, 1996; Stone, Rudd, Ragozzino, & Gold, 1992), children (Benton, Maconie, & Williams, 2007; Benton & Stevens, in press), young adults (Benton & Owens, 1993; Benton, Owens, & Parker, 1994; Martin & Benton, 1999) and older adults (Manning, Hall, & Gold, 1990; Manning, Stone, Korol, & Gold, 1998; Parsons & Gold, 1992). Further, individual differences in people’s ability to metabolize glucose predict cognitive performance (Donohoe & Benton, 2000). These effects on a variety of cognitive functions, such as learning and memory, appear to be driven by changes in the transmitter activity of the cholinergic system (see Messier, 2004 for a review; Ragozzino, et al., 1996; Wenk, 1989).

Thus, glucose not only fuels physical activity, but also cognitive activity. In particular, cognitive tasks that are especially effortful and require self-regulatory resources can cause measureable drops in blood glucose (~6–10 mg/dL). Such tasks are impaired under conditions of low glucose, but performance declines are ameliorated after the consumption of glucose (for an excellent review, see Matthew T. Gailliot & Baumeister, 2007). The present experiments capitalized on this side-effect by incorporating a self-control task as one method of manipulating blood glucose levels.

Gailliot et al. (2007) argue that self-control is effortful, requiring a great amount of energy, and thus, when energy in the form of glucose is not available, self-control suffers. In contrast, in this paper we argue that a process that is relatively effortless and automatic, namely visual perception, is influenced by glucose levels, but for different reasons. To use Gailliot et al.’s metaphor, glucose serves as “fuel” in the context of an effortful process, namely self-control. In contrast, the effortless process of perception is scaled by the “fuel gauge” of the glucose available to perform intended actions in the environment.

Visual Slant Perception

Previous research involving the perception of the slant of hills has shown that people provide different estimates depending on whether the task relates to action planning, or action execution (Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999; Proffitt, et al., 1995; Schnall, et al., 2008). The action planning aspect of slant perception is captured by a verbal estimate, which involves stating the slant of a hill in geometric degrees, and by visual matching, which involves adjusting a disk that represents the cross-section of the hill. The verbal and visual measures assess people’s explicit awareness of slant, and on these measure people tend to dramatically overestimate hill slant. For example, research participants typically estimate a 5° hill to be 20°, or a 10° hill to be 30°. In contrast, action execution is captured by a haptic measure of hill slant, which involves placing the dominant hand on a palmboard that can be adjusted, without sight of the hand, to be parallel to the hill’s incline. This visually-guided action measure is generally accurate and uninfluenced by manipulations of physiological state (Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999). How can this apparent disconnect between the two types of measures be explained? Importantly, the haptic palmboard measure is assessed by asking participants to place their hand on the palmboard without looking, and adjust it to be equivalent to the inclination of the hill in front of them. Therefore, there is no visual feedback when performing this task. In contrast, the explicit verbal and visual reports are made by explicitly deciding on the magnitude of hill slant. The overestimation in explicit perception is useful, and is due to two dissociable mechanisms (Proffitt, 2006). First, slant overestimation is an instance of psychophysical response compression, which allows for greater sensitivity to small changes in slant for shallower slants (which, it should be noted, are the only slants we can walk on and consequently the only slants for which small differences are of any relevance; see Proffitt (2006) for further detail). Second, because these representations inform decisions about action (decisions which must take into consideration costs and benefits), anticipating what would be involved in ascending the hill, what resources would be required, and what resources are available and including this information in explicit perception is adaptive in terms of influencing animals to be cautious and “on the safe side” when planning future action and energy expenditure. Actual navigation and movement within the environment, on the other hand, needs to be precise, however actions do not require a representation of distal layout; they can follow visual control heuristics.

Experiment 1

Overview

The goal of the first experiment was to manipulate participants’ level of blood glucose, and then ask them to make perceptual estimates about a steep hill. Ostensibly as part of a “consumer taste test” study, participants were first asked to consume a blackcurrant flavoured juice drink available in two varieties: one containing glucose fructose syrup, the other containing non-caloric sweetener. We predicted that participants who consumed the sugar drink would have available more metabolic energy, and as a consequence, should perceive the hill to be less steep than participants with less available energy, namely those who consumed the artificially sweetened drink.

Pretesting of Juice

Because it was critical to rule out experimental demand effects, we first tested whether people would be able to taste whether the juice contained sugar or not. Ten participants who did not take part in the subsequent slant estimate experiment blindly sampled approximately 100 ml of juice, and guessed whether the juice contained sugar or sweetener2. Their performance was at chance: Of the five participants who received juice containing sugar, two participants identified it correctly; of the five participants who received juice containing non-caloric sweetener, three participants identified it correctly. In other words, half of the participants correctly guessed the ingredient of the juice, whereas the other half did not. Thus, we were confident that participants could unknowingly be assigned to the high vs. low glucose conditions, and we proceeded with the first experiment.

Method

Participants

Forty-three volunteers recruited from the University of Plymouth community (28 women; mean age: 24.49 years, SD = 5.33) received £4.50 for participating. Data from two participants were excluded because they did not follow instructions.

Stimulus

One grassy hill (29° inclination) on the campus of the University of Plymouth was used, viewed from its base. From the point of where the participant was standing the top of the hill was at a distance of 14.17m, with a straight line distance of 13.44m, and a height differential of 4.50m.

Materials

Drinks

The carbohydrate drink used was 250 ml of a blackcurrant flavoured juice drink (brand name: Ribena®) containing glucose fructose syrup3 with 30.3 grams of sugar and 127.5 calories. The placebo drink was 250 ml of Ribena® Light, which contains 1.3g of sugar and 7.5 calories.

Stroop task

Participants were first presented with a practice card with 20 ‘XXXX’s printed in different colours, and with one practice Stroop card with 20 colour words on it. They were instructed to name the colours of the words from top to bottom, and to do so as quickly as possible, without making any errors. Response times were measured by the experimenter using a stop watch. Subsequently the actual Stroop test with 120 colour words was administered in the same manner.

Weighted backpack

Overestimation of hill slopes is normative—it occurs among most people even when they are not burdened. However, as Bhalla and Proffitt (1999) showed, wearing a heavy backpack causes people to increase their overestimates beyond their normal tendencies to do so. In addition, we were interested in the effects of glucose within especially challenging physical contexts. Thus, all participants were asked to put on a heavy backpack while making their slant estimates. The backpack held exercise free weights approximating 20% of the participant’s weight. Filling the pack with this amount was based on previous research indicating that participants consider this to be a heavy burden, but it does not result in physical pain or back strain during the study (Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999; Proffitt, Stefanucci, Banton, & Epstein, 2003; Schnall, et al., 2008).

Procedure

All testing was done between 9:15 am and 1:00 pm. Participants were asked to refrain from eating for 3 hours prior to reporting for the study. Participants were tested individually and were met by the experimenter at the base of a hill on campus. They were informed that they would be doing several unrelated studies, one involving a consumer preference test, another involving a word reading task, and a third concerning people’s impressions of the environment. Participants each were asked to drink 250 ml of the juice drink, with half of the participants receiving the sugar drink, and the other half receiving the non-caloric sweetener drink, served in an unmarked cup. A chair and small desk where provided next to the hill for the participant for this part of the study.

It was critical that the participants’ blood sugar level was affected by the experimental manipulation at the time of the slant estimates. As stated above, previous research has demonstrated that cognitive activities involving self-control deplete blood glucose (e.g., Matthew T. Gailliot, et al., 2007). Thus, immediately after drinking the juice, participants were administered a Stroop colour naming task. Gailliot et al. (2007) demonstrated that sugar would reach the bloodstream and be available for metabolism by the brain about 10 minutes after ingestion. To ensure that sufficient time was allowed for glucose absorption, another unrelated survey was given, resulting in a delay between drink ingestion and slant estimate ranging from 11 to 16 minutes. In this way, following completion of the Stroop task and the survey participants receiving the sugar drink would be experiencing increased blood glucose levels, while those given the non-caloric drink would be experiencing glucose depletion.

For the next part, participants indicated their body weight on a form, the experimenter put the appropriate weights into the backpack, and then participants walked over to the hill and strapped on the backpack. Each participant then stood at the base of the hill and completed the three hill-slant estimates (verbal, visual and haptic) in a counterbalanced order. For the verbal estimates, participants orally reported hill slant in degrees. As reference, they were told that 0° represented a flat surface and 90° represented a vertical cliff. Visual matching estimates were obtained using a custom-designed metal disc with a moveable pie-shaped piece that can be adjusted to represent any angle between 0° and 90°. A protractor located on the back side of the disc, out of the participant’s sight, allowed the experimenter to determine the set angle of the moveable piece after the participant adjusted it to match the angle of the hill. Haptic estimates were obtained using a custom-designed “palm board”: a flat, hand-sized board mounted on a tripod at slightly above hip-level. The board swivels parallel to the sagittal plane of the participant, and is constrained to 0° in the forward pitch direction and 90° backward pitch. An attached protractor measures the angle set by the participant. The haptic measure required, per instruction, that participants adjust the palm board without looking down at their hand (the palmboard was placed immediately to their right, out of direct view).

After making their hill slant estimates, participants removed the backpack and completed follow-up questionnaires for which they rated their mood (happy, anxious, sad, angry and afraid) on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great degree), their general physical condition (1 = excellent to 6 = poor), their physical condition on that day (1 = excellent to 5 = very unwell), and how often they exercised per week. Before being debriefed and paid, participants were questioned regarding the objective of the experiment. None reported any awareness of the actual purpose.

Results and Discussion

Slant Estimates

Boxplots of all three slant measures were inspected for outliers, and five extreme observations (outside of three box lengths) were identified. Data from these participants were excluded from analyses.

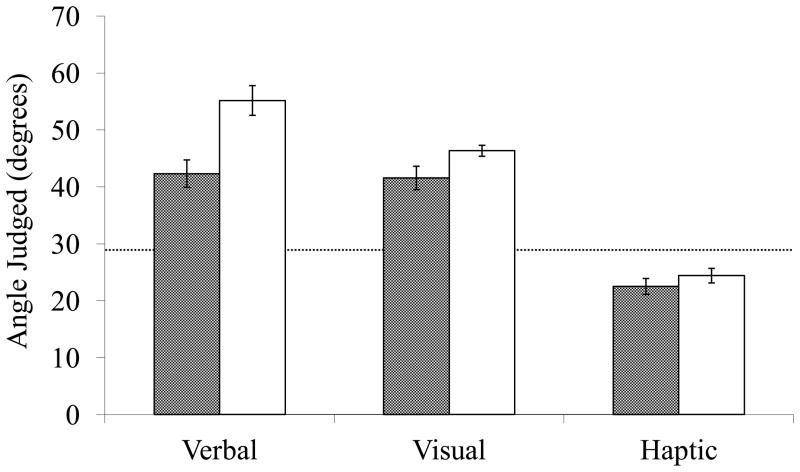

As expected, a between-subjects ANOVA with condition (sugar vs. sweetener) as factor showed that participants who drank juice containing sugar estimated the hill to be less steep on the verbal measure, F (1, 34) = 13.09, p < .001, η2 = .28, and on the visual measure F (1, 34) = 4.44, p < .04, η2 = .12, than did participants who drank juice containing non-caloric sweetener (see Figure 1). In contrast, and consistent with theories of dual visual systems, sugar consumption did not affect haptic estimates F (1, 34) = .99, p < .33.

Figure 1.

Slant estimates for participants consuming sugar-containing juice (grey bars) and non-caloric sweetener-containing juice (white bars). The horizontal dashed line represents the actual slant of the hill (29°). Error bars show ± s.e.m.

Mood

To ascertain that the findings were not due to differences in mood, following previous procedure (Schnall et al., 2008) we first computed a mood composite score by adding up ratings for all five mood items4. This composite score was then subjected to a one-way ANOVA with condition (sugar vs. sweetener) as factor. Participants in both conditions did not differ on self-reported mood, F (1, 34) = 2.38, p < .13. To further confirm that mood did not influence the slant estimates, we repeated the three ANOVAs reported above with the inclusion of self-reported affect as a covariate. There was still a significant effect of condition for the verbal estimates, F (1, 34) = 10.23, p < .003, η2 = .24 and the visual estimates, F (1, 34) = 4.21, p < .05, η2 = .11. In contrast, as in the initial analyses, there was no effect on the haptic estimates, F (1, 34) = .86, p < .36, η2 = .03. Thus, the findings of energetic state on slant estimates remained robust when controlling for differences in self-reported mood.

Physical fitness

Because earlier reports documented effects of physical ability on slant estimates (Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999), we compared the two conditions regarding their reported physical fitness. No differences across conditions were found regarding general physical condition, (p > .41), physical condition on that day (p > .12), or frequency of exercising (p > .25).

The results from Experiment 1 indicate that participants who had consumed a glucose-containing drink perceived a hill’s slant to be less steep than did participants who had consumed a drink containing non-caloric sweetener. Presumably, this is the case because on some level, visual perception reflects the economy of an action, and how easy or difficult it would be to engage with a particular environment, given one’s state of the body. Because climbing a hill while wearing a heavy backpack poses a metabolic challenge, explicit action planning benefits from the apparent slant of the hill being influenced by one’s potential to expend energy. In contrast, visual processes that control action execution, as measured by participants’ haptic estimates, were unaffected by differential energetic demands, because the biomechanics of climbing a hill remain the same regardless of current energetic state.

Experiment 2

The first experiment demonstrated that after performing a demanding cognitive task that might have depleted blood glucose, participants who had consumed a glucose drink perceived a hill to be less steep than participants who had consumed a glucose-free placebo drink. It was assumed that one of the primary consequences of the glucose drink was to raise participants’ blood glucose levels, which in turn influenced their perception of hill slant. However, this assumption was not tested explicitly, and the direct relationship between blood glucose and spatial perception remained unknown.

The aim of Experiment 2 was to replicate the findings of Experiment 1, with the addition of direct measures of blood glucose. Participants’ blood glucose levels were measured on two occasions: a baseline measure was obtained at the start of the experiment, followed by a second measure just before going outside to perform the hill slant estimates.

The results from Experiment 1 also brought to light a potential complication for any experiment in spatial perception. If glucose consumption can cause measurable changes in spatial perception, then individual differences affecting blood glucose levels, for instance dietary habits and the time since the last meal, may add a major source of variance to the data. For example, we would expect participants who happen to have consumed a Snickers bar and a 64-ounce Big Gulp of Mountain Dew (239.8 grams of sugar, combined) just before the experiment to behave differently from participants who skipped breakfast and had their most recent meal 14 hours ago at dinner time the night before.

Furthermore, blood glucose levels alone are by no means entirely synonymous with metabolic energy availability. Other bioenergetic factors are directly involved, as are many seemingly unrelated factors which can have indirect involvement by mediating the effects of glucose. Glucose tolerance, that is, how well the body manages glucose, and glucose usage economy, that is, how much glucose is used for a given task, are both dynamic. For example, a high level of fitness resulting from exercise is associated with superior glucose tolerance and usage economy (Heath, et al., 1983; Morgan, et al., 1995) Given that available metabolic energy influences spatial perception, any number of things that affect the storage, availability, or economical usage of metabolic energy could reasonably be expected to also influence spatial perception. For example, the effects of a poor night’s sleep, fatigue from exercising at the gym, cognitive exhaustion from taking a big exam, or stress from personal problems are but a few likely factors. Even if some influences are minor, the combined effect of many or all of these factors may cause unexplained variability in the data if they are unaccounted for. This variability from unmeasured individual differences will only serve to obscure the effects of interest. If this is indeed the case, it should be possible to eliminate such variance by assessing individual differences in theoretically plausible factors, such as sleep, fitness, and physical and mental fatigue and include these in the statistical model.

Thus in addition to recording blood glucose, for Experiment 2 a number of existing assessment tools that covered a wide range of possible bioenergetic factors were compiled, and these were combined with a series of custom-designed bioenergetically-relevant assessment questions to create one large test battery, which we hereafter refer to as the Bioenergetics Test Battery (BTB). The BTB covers sleep, fitness, exercise, nutrition, fatigue, stress, cognitive activity, and mood. We expected to replicate the effect demonstrated in Experiment 1, namely that high blood glucose would make a hill appear less steep compared to low blood glucose. Furthermore, we expected to be able to refine our findings by taking into account individual differences in bioenergetic responses.

Method

Participants

Fifty-six volunteers from the University of Virginia community (29 women, 1 unreported; mean age: 23.28 years, SD = 5.71) received $10 for participating. Participants were required to have normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and have no history of diabetes or cardiac problems, and were urged not to participate if they had any phobia of needles or the sight of blood. Four participants did not contribute any glucose data due to experimenter error or equipment failure, 5 participants failed to follow instructions, and 1 participant revealed advanced knowledge of slant perception during subsequent probing regarding the experiment’s purpose. Data of these 10 participants were excluded.

Stimulus

One paved hill (5.6° inclination) on the grounds of the University of Virginia was used, viewed from its base. From the point of where the participant was standing the top of the hill was at a distance of 47.30m, with a straight line distance of 47.07m, and a height differential of 4.62m.

Materials

Drinks

The carbohydrate drink was 12 fluid ounces (355 ml) of Coca-Cola® containing 39 grams of glucose. The placebo drink was 12 fluid ounces (355 ml) of Coke Zero®, which is sweetened with artificial sweetener and contains zero calories5.

Weighted backpack

As in Experiment 1, a backpack was used to hold exercise free weights approximating 20% of the participant’s self-reported weight.

Blood Glucose Meter

A Roche Accu-Chek Compact Plus blood glucose meter was used to record blood glucose levels.

Stroop task

In contrast to Experiment 1, the Stroop task was presented on a computer screen. On each trial, a target colour word was presented using either red, yellow, green, or blue coloured text in the centre of a black screen. Two possible response options were simultaneously presented for each trial in the bottom left and bottom right of the screen. Participants indicated their response by moving a joystick left or right to correspond to the screen position of the desired response option. Following a response, the screen remained blank for one second between trials. The task lasted for 10 minutes, with no fixed number of trials.

Bioenergetics Test Battery

A series of questionnaires was administered by computer and standard paper and pencil formats. These covered items relating to sleep, exercise, nutrition, fatigue, mood, and stress (see Appendix).

Procedure

Participants were asked not to eat or drink anything other than water for 3 hours before their appointment time. Upon arrival at the lab, participants were given a general description of the experiment, which emphasized that blood tests would be involved. Participants were discouraged from taking part if they were afraid of needles or the sight of blood, because a large anxiety response could cause unexpected changes in blood glucose levels or glucose tolerance (Surwit, Schneider, & Feinglos, 1992). After providing informed consent, participants’ baseline blood glucose levels were measured. Next, participants were served their drink, either Coke or Coke Zero, in an unmarked plastic cup and asked to drink it as quickly as possible without causing themselves any discomfort. While consuming the drink, participants indicated their weight range on the provided form. Participants then engaged in the Stroop task for 10 minutes. Upon completion of the task, participants’ blood glucose levels were measured a second time.

The experimenter next escorted participants outside to the base of a hill, where they put on the weighted backpack. The three hill slant measures were administered as in Experiment 1, in counterbalanced order. Participants then returned to the lab to complete the BTB. Finally, the experimenter assessed participants’ potential suspicions about the study’s purpose and any previous knowledge of hill perception. Once participants were debriefed and informed of the two possible drink conditions, they were asked to guess, given a 50/50 chance, whether they had been given regular Coke or Coke Zero.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses proceeded in three stages: First, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis on the BTB data with oblique rotation to identify factor structure describing which of the variables loaded on the same factor. Second, we aggregated the resulting grouped variables into predictor variables. Finally, for the main analyses, we used the predictor variables to account for inter-individual variation, together with variables defining drink condition and measure type in a linear mixed-effects model to predict slant estimates.

Results and Discussion

Manipulation check

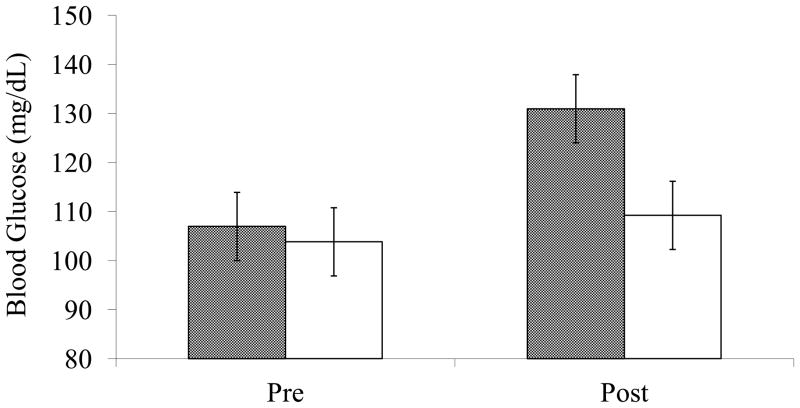

To demonstrate that relative to baseline, consuming a drink containing sugar raised blood glucose levels, whereas consuming a drink containing sweetener did not, a repeated-measures ANOVA with time (pre-test vs. post-test) as repeated factor, and drink condition (sugar vs. sweetener) as between-subjects factor was conducted on blood glucose measurements. As expected, there was a significant interaction of time and condition, F (1, 44) = 15.24, p < .001. Planned comparisons confirmed that although the sugar (M = 106.96, SD = 23.04) and sweetener (M = 103.83, SD = 16.60) conditions did not differ at the beginning of the study, F (1, 44) = .28, p > .60, participants in the sugar condition (M = 139.48, SD = 23.44) had significantly higher levels of blood glucose after having consumed the drink than participants in the sweetener condition (M = 109.22, SD = 21.45), F (1, 44) = 20.86, p < .001. Thus, as shown in Figure 2, we established that the drink manipulation indeed led to increased blood glucose levels in the sugar condition, relative to the sweetener condition.

Figure 2.

Blood glucose levels for participants before and after consuming the glucose drink (grey bars) and placebo drink (white bars). Error bars show ± s.e.m.

To test for the possibility of demand characteristics due to explicit or implicit awareness of the drink manipulation, participants guesses about which type of cola they had ingested were analyzed with regards to which drink they had actually ingested. Eleven participants had missing guess data and were excluded from the analysis. Of those participants remaining, 12 in the glucose condition and 10 in the placebo condition guessed correctly, while 4 in the glucose condition and 9 in the placebo condition guessed incorrectly6. A Fisher’s exact test indicated that participants were not able to guess reliably about which version of the drink they had been given (p = 0.293, two-tailed).

Factor analysis

In order to include data from the BTB to explain variance due to individual differences, a factor analysis was used to reduce the data to a small number of factors. Because we expected these factors to be correlated, Promax rotation was used. Although the current experiment included 46 participants, BTB data for 110 participants was available from related experiments and was used to increase the fit and accuracy of the factor analysis7. A series of factor analyses were run using eigenvalue analyses to determine the optimal number of factors to fit. Variables with higher uniqueness scores were scrutinized based on their theoretical bioenergetic effect, and several were removed. For the final set of data, eigenvalue analysis indicated that four factors were optimal. These factors were fitted from the questionnaire data to produce regression scores for each participant. The questionnaires and subscales included in the analysis are shown with their factor loadings in Table 1. The factor intercorrelation matrix is shown in Table 2. As can be seen from the factor loadings, Factor 1 was loaded heavily onto mood, cognitive fatigue, stress, and some sleep related indicators, Factor 2 for indicators involving physical fatigue and exercise/fitness, Factor 3 for indicators involving sleep, and Factor 4 for items relating to length of time since waking and amount and level of cognitive activity engaged in the hours prior to the experiment.

Table 1.

Factor Loadings

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CESD | ||||

| Fatigue | .924 | |||

| Sleep | .523 | −.103 | .381 | |

| Corrected Total | .915 | |||

| FSS | .519 | .235 | −.219 | .108 |

| MFI | ||||

| General | .633 | .257 | .124 | |

| Physical | .827 | .147 | ||

| Activity | .782 | .118 | −.128 | |

| Motivation | .450 | .380 | ||

| Mental | .472 | .323 | ||

| PSQI | ||||

| Sleep Quality | .194 | .894 | ||

| Sleep Latency | .512 | |||

| Sleep Duration | .254 | −.152 | .317 | |

| Habitual Sleep Efficiency | −.111 | .301 | .236 | |

| Sleep Disturbances | .249 | .189 | ||

| Daytime dysfunction | .729 | |||

| PSS | .631 | .145 | ||

| SEQ | .157 | −.610 | −.156 | |

| BQ | ||||

| Cognitive Activity | −.168 | .857 | ||

| Mental Fatigue | .129 | .848 | ||

| Anaerobic Exercise | −.204 | .107 | ||

| Aerobic Exercise | −.16 | −.379 | ||

| Exercise total per week | −.503 | −.123 | ||

| Sleep Quality (last night) | .373 | |||

| Sleep Quality (past 7) | −.149 | .121 | .749 | .135 |

| Time difference between usual vs. today’s wake-up times | .122 | −.221 | ||

| Time between normal bedtime and bedtime last night | −.101 | .111 | ||

| Time since waking at start of experiment | −.224 | .541 | ||

| Time difference between usual amount of sleep vs. last night | −.457 | .221 | −.180 | |

Note: refer to Appendix for acronyms and item descriptions. Numbers with absolute value greater than .500 are in bold.

Table 2.

Factor Intercorrelation Matrix

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 1.000 | |||

| Factor 2 | −.484 | 1.000 | ||

| Factor 3 | −.487 | .063 | 1.000 | |

| Factor 4 | −.282 | −.032 | .237 | 1.000 |

Main model

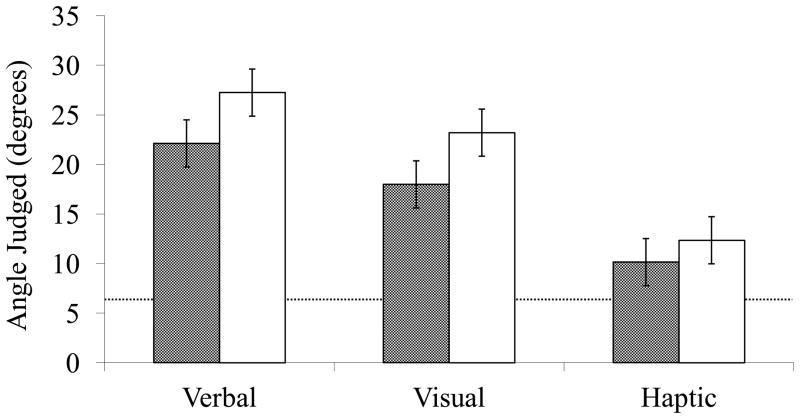

A linear mixed-effects model was used to investigate the possible predictors of slant estimates. Three grouping variables were dummy-coded for the 3 measure types, and 3 experimental variables were effect-coded for the 3 measure types (−0.5 = Placebo, +0.5 = Glucose). Slant estimates were predicted from the additive effects of these 6 terms and the 4 Factors, with a subject-level random intercept. As shown in Table 3, the analysis revealed statistically significant coefficients for the intercepts of all 3 measure types, the glucose manipulation for verbal and visual measures, and Factors 1, 2, and 4. As expected, participants who ingested a placebo drink without glucose perceived the hill to be steeper than participants who ingested a glucose drink, as reflected in verbal (β = 5.13, p < .05) and visual (β = 5.22, p < .05) estimates. Consistent with theories of dual visual systems, there was no statistically significant effect of the glucose manipulation on haptic slant estimates. In addition, individual differences also predicted differences in hill slant perception: higher values of Factor 1 were predictive of higher slant estimates (β = 1.44, p < .05) indicating that participants who had greater levels of fatigue, poorer sleep, higher stress levels, and higher levels of depression perceived the hill to be steeper; higher values of Factor 2 were also predictive of higher slant estimates (β = 2.10, p < .05), indicating that participants who were experiencing greater physical fatigue, and who exercised less often and for shorter durations perceived the hill to be steeper; higher values of Factor 4 again were predictive of higher slant estimates (β = 2.52, p < .05), indicating that participants who had been awake longer or had engaged in more hours of cognitive activity on the day of the experiment and were experiencing more mental fatigue perceived the hill to be steeper. There was a non-significant trend for Factor 3 (β = 1.44, p = .07) in the expected direction, suggesting again that participants with poorer sleep quality may have perceived the hill to be steeper. Across both drink conditions, verbal (β = 27.25, p < .05) and visual (β = 23.21, p < .05) estimates were significantly greater than haptic (β = 12.35, p < .05) estimates. The pattern and magnitude of this difference between measures was as expected based on previous experiments (Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999; Proffitt, et al., 1995). See Figure 3 for predicted slant estimates of all three measures when controlling for individual differences in bioenergetic factors.

Table 3.

Linear Mixed Effects Model Results for Predictors of Verbal and Visual Slant Estimates

| Value | Std. Error | df | t-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal Intercept | 27.25 | 1.88 | 87 | 22.93 | <.001 |

| Glucose (Verbal) | −5.13 | 2.38 | 87 | −2.16 | .034 |

| Visual Intercept | 23.21 | 1.88 | 87 | 19.53 | < .001 |

| Glucose (Visual) | −5.22 | 2.38 | 87 | −2.19 | .031 |

| Haptic Intercept | 12.35 | 1.19 | 87 | 10.39 | < .001 |

| Glucose (Haptic) | −2.21 | 2.38 | 87 | −.93 | .356 |

| Factor 1 | 1.44 | 0.71 | 41 | 2.02 | .049 |

| Factor 2 | 2.10 | 0.85 | 41 | 2.47 | .018 |

| Factor 3 | 1.44 | 0.77 | 41 | 1.88 | .067 |

| Factor 4 | 2.52 | 0.92 | 41 | 2.75 | .009 |

Figure 3.

Predicted values for hill slant estimates for participants consuming the glucose drink (grey bars) and placebo drink (white bars) from an LME model incorporating individual differences from the BTB. The horizontal line represents the actual slant of the hill (5.6°). Error bars show ± s.e.m.

These results are consistent with those from Experiment 1, and support the original hypothesis that visual perception reflects the economy of an action and the resources available to the body for performing that action. The implication of Experiment 1 that blood glucose is one such resource was explicitly tested and supported by Experiment 2. Further, the hypothesis that individual differences regarding many additional bioenergetic factors should affect visual perception was strongly supported, with robust effects in the hypothesized direction on the order of two and three degrees change in perceived slant. As expected, individual differences on factors which would decrease participants’ ability to act on the hill, such as fatigue, physical fitness, and so on were associated with perception of the hill as being steeper. Importantly, it was only when also taking into account these individual differences that the effect of the glucose manipulation became apparent. One possibility, although speculative, is that because in Experiment 2 we tested participants at a much shallower hill (5.6°) than in Experiment 1 (29°), the effects of glucose were less pronounced. Because decreased levels of glucose would have more deleterious effects when faced with a steep hill compared to a shallow hill, detecting the influence of the glucose manipulation critically depended on partialing out systematic individual differences related to participants’ current physical state.

As with Experiment 1 and a multitude of previous perception research, unconscious visual perception for control of action was unaffected by blood glucose and other bioenergetic factors: Regardless of a perceiver’s ability to climb a hill as affected by body state and available energy resources, the mechanics of doing so remain unchanged.

General Discussion

Two experiments provided evidence that metabolic energy, manipulated in the form of blood glucose, influenced the visually perceived layout of the environment: A hill appeared shallower to participants who had previously consumed a drink containing sugar, compared to participants who had consumed a drink containing non-caloric sweetener. To our knowledge, the present research is the first direct demonstration that, in appropriate circumstances, visual perception relates spatial layout to the metabolic energy available to act in the environment. While, in a single instance, walking up a short hill or ingesting 40 g of glucose represents a small change compared to total bodily energy stores, it must be kept in mind that perception (in our proposal) supports decisions that result in actions such as these many, many times every day, and decisions that result in avoiding such actions a far larger number of times every day. Essentially, those negligible amounts add up (or could add up, were the actions not avoided) to quite significant amounts, which could negatively affect an animal’s chances for survival. Our results are consistent with previous research indicating that action-relevant resources moderate spatial perception: Being encumbered, fatigued, unfit, elderly or in declining health (Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999; Proffitt, et al., 1995). All of these studies manipulated variables thought to affect bioenergetic resources, and their obtained results were interpreted as showing that perception is constrained by the anticipated bioenergetic costs of acting on the environment (Proffitt, 2006). Glucose is a primary candidate for potential substrates to be included in this conceptualization of bioenergetic resources as it relates to action-specific perception. In fact, the manipulations in these studies can be explained theoretically by glucose: increased effort, such as that caused by being encumbered, can be identically explained as an increase in the amount of glucose required for an action; physical fatigue is defined in large part by diminished glucose stores in the muscles and liver (Coyle, et al., 1986); physical fitness affects glucose tolerance and glucose usage economy (Eriksson & Liridgärde, 1996; Kelley & Goodpaster, 1999; Richter, Turcotte, Hespel, & Kiens, 1992; Wareham, Wong, & Day, 2000); and glucose tolerance and usage economy decline in old age (Shimokata, et al., 1991; Stolk, et al., 1997; Unwin, Shaw, Zimmet, & Alberti, 2002). The current studies provide direct support for the notion that blood glucose is the underlying bioenergetic resource. Further, blood glucose is but one of many physiological factors that may be relevant to the study of action-specific perception: thus, there are a host of potential physiological measures (such as calorimetry, electrocardiography, respiratory rate and volume measurements, blood oxygenation, electromyography, and blood lactate levels) that can provide dynamic data to further refine experimental methods beyond standard tests of main effects.

Individual Differences in Perception of Spatial Layout

In addition to replicating Experiment 1’s effect of blood glucose levels on slant perception, Experiment 2 demonstrated that taking into account bioenergetically relevant individual differences such as fatigue, physical fitness, sleep quality and so on can refine the analyses. Thus, it may be advisable to assess these variables in future experiments in order to maximally account for potential error variance related to these factors. Further, it may be that including these individual differences might be especially critical when investigating less extreme physical environments, such as relatively shallow hills, or relatively easily walkable distances, because perceptual differences across conditions might be more easily obscured when dealing with effects of small magnitude. Analysis of the specific individual differences measured in Experiment 2 also supported the initial hypothesis that energetic costs and resources are reflected in visually perceived spatial layout.

Alternative Explanations

Although it was not possible in two experiments to address all possible alternative explanations, the present findings are inconsistent with the following candidate explanations:

Experimental Demand Characteristics

In contrast to earlier experiments, the two experiments reported in this paper manipulated an action-relevant variable while keeping participants unaware that this was taking place. First, participants did not know that the actual purpose of the study was to look at the relationship between consuming the drink and their estimates of hill slant. Therefore, participants were not primed with the notion that consuming a drink might affect physical performance (see Friedman & Elliot, 2008). Furthermore, participants were blind to their experimental conditions; both groups were treated exactly the same except for the presence or absence of glucose in their drink and participants were unable to reliably guess which drink they had ingested. Finally, individual differences as assessed by the bioenergetic test battery can predict perceived slant; this variability came in with participants—it was not manipulated and therefore was immune to any possible unintentional changes by the experimenter. Thus, it is very unlikely that our results were due to experimental demand characteristics, and our findings remained very similar to those obtained in earlier studies (Bhalla, Proffitt, Rossetti, & Revonsuo, 2000; Proffitt, et al., 1995; Proffitt, Creem, & Zosh, 2001). This accumulating body of evidence further increases the confidence in the conclusions derived from these studies, as well as in the underlying theoretical account (Proffitt, 2006).

Mood

Both experiments showed effects of blood glucose while statistically controlling for mood. In Experiment 1, we co-varied out mood differences and the previously obtained effects on the verbal and visual estimates remained intact as did the previous lack of effect on the haptic measure. In addition, considering individual differences in self-reported current mood accounted for unique individual variance, as demonstrated in Experiment 2. Thus, it seems likely that although when manipulated directly, mood can influence slant perception such that a sad mood leads to the hill appearing more steep than a happy mood (Riener, 2007), our experiments showed an effect of blood glucose that was independent of mood.

Perception Vs. Self-Regulation

An important consideration is whether the present findings might be interpreted differently from the perspective of self-regulation approaches (M. T. Gailliot, 2008; Matthew T. Gailliot & Baumeister, 2007; Matthew T. Gailliot, et al., 2007). It might be possible that our findings were due to the glucose influencing perception via the route of self-control, an effortful cognitive process, rather than via the route of participants’ bodily metabolic state. In other words, perhaps the effects were due to the influence of glucose on the brain and on cognitive processes, rather than the influence of glucose on peripheral metabolic energy. We cannot conclusively rule out that glucose might also have effects on the brain (e.g., M. T. Gailliot, 2008), however for several reasons, we believe that our effects are primarily due to peripheral effects of glucose. First, previous manipulations such as wearing a backpack, exercising heavily, and so on (Bhalla & Proffitt, 1999; Proffitt, et al., 1995) all demonstrated effects that are consistent with the findings reported in this paper. Second, according to recent evidence, as far as self-regulatory processes are concerned, relatively complex and effortful tasks are affected by low glucose levels, but not easy ones (Masicampo & Baumeister, 2008). Other researchers also observed that only complex and difficult cognitive processes involving self-control were impaired by low glucose levels, but not easy cognitive tasks (Benton, et al., 1994; Donohoe & Benton, 2000; Owens & Benton, 1994). In contrast, the perceptual estimates that we asked participants to provide were made quickly and with little effort. Our results do not speak to issues of effortful self-control; rather, they concern the anticipating of an effortful action, namely of climbing a hill while wearing a heavy backpack, which is then reflected in the relatively simple task of making slant estimates.

Conclusion

Previous research has demonstrated that manipulating the effort involved in performing an action influences the perception of the physical environment associated with that action. Although such studies have inferred that the manipulations involved changes in metabolic energy, the two experiments reported in this paper were the first to test this conjecture directly. Participants who had ingested a drink containing readily absorbable glucose estimated two different hills to be less steep than participants whose drink was sugar-free. By the economy of action account (Proffitt, 2006) perception relates the optically specified spatial layout of the environment to both the anticipated bioenergetic costs of performing an intended action and the bioenergetic resources available.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (BCS 0518835) to S. Schnall, G. Clore, and D. Proffitt. We thank Judy DeLoache for comments on an earlier version of the paper, Steve Boker for help with exploratory factor analysis, and Laura Lantz, Stephen Dewhurst, Blair Hopkins, Allison Brennan, and Amelia Swafford for assistance with data collection.

Appendix: The Bioenergetics Test Battery

A. Pre-existing Assessment Tools

-

CESD: Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Note: Extracted “Fatigue” and “Sleep” subscale scores from total score to allow separate loadings in factor analysis; “corrected total” score reflects total score without these subscales.

-

FSS: Fatigue Severity Scale

Krupp, L. B., LaRocca, N. G., Muir-Nash, J., Steinberg, A. D. (1989). The Fatigue Severity Scale. Aplication to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erthematosus. Archives of Neurology, 46, 1121–1123

-

MFI: Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory

Smets, E. M. A., Garssen, B., Bonke, B., & De Haes, J. C. J. M. (1995). The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 39, 315–325.

Subscales:

General fatigue

Physical fatigue

Activity dependent fatigue

Motivational fatigue

Mental fatigue

-

PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. I., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28, 193–213.

Subscales:

Subjective sleep quality

Sleep latency (time from getting in bed to falling asleep)

Sleep duration

Habitual sleep efficiency

Sleep disturbances

Use of sleeping medication

Daytime dysfunction

-

PSS: Perceived Stress Scale

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

-

SEQ: Spatial Experience Questionnaire

McDaniel, E., Guay, R., Ball, L., & Kolloff, M. (1978). A spatial experience questionnaire and some preliminary findings. Ann. Meet. Am. Psychol. Assoc., Toronto.

B. Custom Assessment Items

-

Physical

Age, gender, height, weight, vision.

-

Exercise, fitness, and fatigue

Normal workout frequency, normal workout duration, workout frequency and duration past 7 days, hours since most recent workout, duration of most recent workout (each assessed separately for anaerobic and aerobic exercise).

-

Cognitive

Self-rated current mental fatigue, hours of cognitive work today (time in class, time studying, etc.), number of exams today.

-

Sleep

Sleep quality, sleep duration (separately for both last night and past 7 days), bedtime last night, wakeup time this morning, sleep duration last night.

Footnotes

In a recent article, Durgin et al. (in press) presented an experiment, the results of which were interpreted as showing that the influence of wearing a heavy backpack on verbal reports of hill slant may be due to demand characteristics, not changes in perception. The experimental conditions in Durgin et al.’s study were so different from the original Bhalla and Proffitt (1999) study, that there are reasons doubt the generalizability of the former study (Proffitt, in press). The participants in the Durgin et al. study viewed a 2 m long ramp; those in Bhalla and Proffitt viewed expansive hills. When drawing generalizations from one study to another, equating experimental conditions is always important; moreover, from an embodied perspective on perception, equating the opportunities for action matters as well.

Each participant was shown the two drink bottles with clear indication of how they were sweetened, and was told that they would be asked to take a sip of drink from an unmarked cup. The experimenter then turned away from the participant, and out of the participant’s view, poured the drink from one of the two bottles. After tasting the drink the participant was asked which bottle the drink came from, that is, whether it was the regular or the “light” version of the juice.

According to information obtained from the drink’s manufacturer GlaxoSmithKline, the juice drink contains glucose to fructose at a ratio of 1.4 to 1.

Happiness was reverse-coded to create the composite score.

Both versions of cola contain the same amount of caffeine (34.5 mg). Because the focus of our work was on glucose, we did not investigate any potential effects of caffeine on spatial perception.

Caution needs to be used when interpreting these numbers because participants guessed their drink condition only after the debriefing. Therefore, it is possible that some participants might have guessed their drink condition based on whether they gave relatively high or low slant estimates. If this were the case, more participants than expected would end up correctly guessing their drink condition.

The additional 64 participants (50 women, mean age: 18.62 years, SD = 1.16) were tested in an unpublished study with similar experimental methods to Experiment 2, in which the caffeine content of the drink was a variable.

Contributor Information

Simone Schnall, University of Plymouth.

Jonathan R. Zadra, University of Virginia

Dennis R. Proffitt, University of Virginia

References

- Achten J, Halson SL, Moseley L, Rayson MP, Casey A, Jeukendrup AE. Higher dietary carbohydrate content during intensified running training results in better maintenance of performance and mood state. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2004;96(4):1331–1340. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00973.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton D, Maconie A, Williams C. The influence of the glycaemic load of breakfast on the behaviour of children in school. Physiology & Behavior. 2007;92(4):717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton D, Owens DS. Blood glucose and human memory. Psychopharmacology. 1993;113(1):83–88. doi: 10.1007/BF02244338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton D, Owens DS, Parker PY. Blood glucose influences memory and attention in young adults. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32(5):595–607. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton D, Parker PY, Donohoe RT. The supply of glucose to the brain and cognitive functioning. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1996;28(4):463–479. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000022537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton D, Stevens MK. The influences of a glucose containing drink on the behaviour of children in school. Biological Psychology. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.03.007. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla M, Proffitt DR. Visual-motor recalibration in geographical slant perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1999;25(4):1076–1096. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.25.4.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla M, Proffitt DR, Rossetti Y, Revonsuo A. Beyond Dissociation: Interaction Between Dissociated Implicit and Explicit Processing. John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2000. Geographical slant perception: Dissociation and coordination between explicit awareness and visually guided actions; pp. 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle EF. Fluid and fuel intake during exercise. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2004;22(1):39–55. doi: 10.1080/0264041031000140545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle EF, Coggan AR, Hemmert MK, Ivy JL. Muscle glycogen utilization during prolonged strenuous exercise when fed carbohydrate. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1986;61(1):165–172. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Jackson DA, Broadwell MS, Queary JL, Lambert CL. Carbohydrate drinks delay fatigue during intermittent, high-intensity cycling in active men and women. International Journal of Sport Nutrition. 1997;7:261–273. doi: 10.1123/ijsn.7.4.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe RT, Benton D. Glucose tolerance predicts performance on tests of memory and cognition. Physiology & Behavior. 2000;71(3–4):395–401. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgin FH, Baird JA, Greenburg M, Russell R, Shaughnessy K, Waymouth S. Who is being deceived? The experimental demands of wearing a backpack. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.5.964. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson KF, Liridgärde F. Poor physical fitness, and impaired early insulin response but late hyperinsulinaemia, as predictors of NIDDM in middle-aged Swedish men. Diabetologia. 1996;39(5):573–579. doi: 10.1007/BF00403304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman R, Elliot AJ. Exploring the influence of sports drink exposure on physical endurance. Psychology of Sport & Exercise 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Gailliot MT. Unlocking the Energy Dynamics of Executive Functioning: Linking Executive Functioning to Brain Glycogen. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(4):245–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gailliot MT, Baumeister RF. The Physiology of Willpower: Linking Blood Glucose to Self-Control. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2007;11(4):303–327. doi: 10.1177/1088868307303030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gailliot MT, Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Maner JK, Plant EA, Tice DM, et al. Self-Control Relies on Glucose as a Limited Energy Source: Willpower Is More Than a Metaphor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(2):325–336. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold PE. Glucose modulation of memory storage processing. Behavioral and neural biology. 1986;45(3):342–349. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(86)80022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath GW, Gavin JR, 3rd, Hinderliter JM, Hagberg JM, Bloomfield SA, Holloszy JO. Effects of exercise and lack of exercise on glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1983;55(2):512–517. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.2.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley DE, Goodpaster BH. Effects of physical activity on insulin action and glucose tolerance in obesity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1999;31(11):S619–S623. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning CA, Hall JL, Gold PE. Glucose effects on memory and other neuropsychological tests in elderly humans. Psychological Science. 1990;1(5):307–311. [Google Scholar]

- Manning CA, Stone WS, Korol DL, Gold PE. Glucose enhancement of 24-h memory retrieval in healthy elderly humans. Behavioural Brain Research. 1998;93(1–2):71–76. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PY, Benton D. The influence of a glucose drink on a demanding working memory task. Physiology & Behavior. 1999;67(1):69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masicampo EJ, Baumeister RF. Toward a Physiology of Dual-Process Reasoning and Judgment: Lemonade, Willpower, and Expensive Rule-Based Analysis. Psychological Science. 2008;19(3):255–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNay EC, McCarty RC, Gold PE. Fluctuations in Brain Glucose Concentration during Behavioral Testing: Dissociations between Brain Areas and between Brain and Blood. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2001;75(3):325–337. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2000.3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier C. Glucose improvement of memory: a review. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;490(1–3):33–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier C, White NM. Memory improvement by glucose, fructose, and two glucose analogs: a possible effect on peripheral glucose transport. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1987;48(1):104–127. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(87)90634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D, Bransford DR, Costill DL, Daniels JT, Howley ET, Krahenbuhl GS. Variation in the aerobic demand of running among trained and untrained subjects. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1995;27(3):404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray R, Eddy DE, Murray TW, Seifert JG, Paul GL, Halaby GA. The effect of fluid and carbohydrate feedings during intermittent cycling exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1987;19:597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray R, Paul G, Seifert J, Eddy D, Halaby G. The effects of glucose, fructose, and sucrose ingestion during exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1989;21:275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DS, Benton D. The impact of raising blood glucose on reaction time. Neuropsychobiology. 1994;30(2):106–113. doi: 10.1159/000119146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MW, Gold PE. Glucose enhancement of memory in elderly humans: An inverted-U dose-response curve. Neurobiology of Aging. 1992;13(3):401–404. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90114-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Schweiger U, Pellerin L, Hubold C, Oltmanns KM, Conrad M, et al. The selfish brain: competition for energy resources. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28(2):143–180. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt DR. Embodied Perception and the Economy of Action. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2006;1(2):110–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt DR. Affordances Matter in Geographical Slant Perception: Reply to Durgin, Baird, Greenburg, Russell, Shaughnessy, and Waymouth. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.5.970. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt DR, Bhalla M, Gossweiler R, Midgett J. Perceiving geographical slant. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1995;2(4):409–428. doi: 10.3758/BF03210980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt DR, Creem SH, Zosh WD. Seeing mountains in mole hills: Geographical-slant perceptions. Psychological Science. 2001;12(5):418–423. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt DR, Stefanucci J, Banton T, Epstein W. The role of effort in perceiving distance. Psychological Science. 2003;14(2):106–112. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino ME, Unick KE, Gold PE. Hippocampal acetylcholine release during memory testing in rats: Augmentation by glucose. Vol. 93. National Academy of Sciences; 1996. pp. 4693–4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter EA, Turcotte L, Hespel P, Kiens B. Metabolic responses to exercise. Effects of endurance training and implications for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1992;15(11):1767–1776. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.11.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riener C. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Virginia; Charlottesville, VA: 2007. An effect of mood on the perception of slant. [Google Scholar]

- Schnall S, Harber KD, Stefanucci JK, Proffitt DR. Social support and the perception of geographical slant. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:1246–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimokata H, Muller DC, Fleg JL, Sorkin J, Ziemba AW, Andres R. Age as independent determinant of glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 1991;40(1):44–51. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolk RP, Pols HAP, Lamberts SWJ, Jong PTVMd, Hofman A, Grobbee DE. Diabetes Mellitus, Impaired Glucose Tolerance, and Hyperinsulinemia in an Elderly Population The Rotterdam Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;145(1):24–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone WS, Rudd RJ, Ragozzino ME, Gold PE. Glucose attenuation of memory deficits after altered light-dark cycles in mice. Psychobiology. 1992;20:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Surwit RS, Schneider MS, Feinglos MN. Stress and diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1992;15(10):1413–1422. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.10.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N, Shaw J, Zimmet P, Alberti KGMM. Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycaemia: the current status on definition and intervention. Diabetic Medicine. 2002;19(9):708–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utter AC, Kang JIE, Nieman DC, Dumke CL, McAnulty SR, Vinci DM, et al. Carbohydrate Supplementation and Perceived Exertion during Prolonged Running. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2004;36(6):1036–1041. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000128164.19223.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wareham NJ, Wong MY, Day NE. Glucose Intolerance and Physical Inactivity: The Relative Importance of Low Habitual Energy Expenditure and Cardiorespiratory Fitness. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;152(2):132–139. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh RS, Davis JM, Burke JR, Williams HG. Carbohydrates and physical/mental performance during intermittent exercise to fatigue. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2002;34(4):723–731. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200204000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk GL. An hypothesis on the role of glucose in the mechanism of action of cognitive enhancers. Psychopharmacology. 1989;99(4):431–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00589888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]