Abstract

Objectives

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins regulate key cellular fate decisions including proliferation and apoptosis. Over-expression of STAT3 induces tumor growth. We hypothesized that a novel small molecule inhibitor derived from curcumin (FLLL32) that targets STAT3 would induce cytotoxicity in STAT3 dependent HNSCC cells and would sensitize tumors to cisplatin.

Design

Basic science. Two HNSCC cell lines, UM-SCC-29 and -74B, were characterized for cisplatin sensitivity. Baseline expression of STAT3 and other apoptosis proteins was determined. The FLLL32 IC50 dose was determined for each cell line and the effect of FLLL32 treatment on the expression of phosphorylated STAT3 and other key proteins was elucidated. The anti-tumor efficacy of cisplatin, FLLL32 and combination treatment was measured. The proportion of apoptotic cells after cisplatin, FLLL32 or combination therapy was determined.

Results

The UM-SCC-29 cell line is cisplatin resistant and the UM-SCC-74B cell line is sensitive. Both cell lines express STAT3, phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) and key apoptotic proteins. FLLL32 downregulates the active form of STAT3, pSTAT3, in HNSCC cells and induces a potent anti-tumor effect. FLLL32, alone or with cisplatin, increases the proportion of apoptotic cells. FLLL32 sensitized cisplatin resistant cancer cells, achieving an equivalent tumor kill with a four-fold lower dose of cisplatin.

Conclusions

FLLL32 monotherapy induces a potent anti-tumor effect and sensitizes cancer cells to cisplatin, permitting an equivalent or improved anti-tumor effect at lower doses of cisplatin. Our results suggest that FLLL32 acts by inhibiting STAT3 phosphorylation, reduced survival signaling, increased susceptibility to apoptosis, and sensitization to cisplatin.

INTRODUCTION

According to the American Cancer Society, there were approximately 48,000 new cases of head and neck cancer resulting in 11,000 deaths in the United States in 20091. The overall 5-year survival for head and neck cancer has remained unchanged over the past three decades. This has driven the search for novel therapeutic agents that may obviate the need for or, alternatively, enhance the effect of currently used treatment regimens.

Platinum-based agents such as cisplatin form the mainstay of currently used chemotherapeutic regimens for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HSNCC)2. However, head and neck cancers often demonstrate significant resistance to cisplatin, acquired through repeated treatment cycles or as an inherent characteristic of the cancer2–4. Cisplatin resistance is a major factor in disease relapse. The resulting locoregional spread of disease and later recurrence are considered the main obstacles to improving outcome in head and neck cancer4. Cisplatin resistance also has implications for ongoing treatment since relatively minor increases in resistance necessitate significant dose escalations which result in increased toxicity5. The anti-tumor function of cisplatin is mediated by the development of DNA-platinum monoadducts and cross-links that can lead to DNA double strand breaks during the process of replication. These, in turn, induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis5–6. Small molecule inhibitors of key pathways involved in apoptosis, differentiation and cell growth may potentially improve the prognosis of head and neck cancer by sensitizing cancer cells, at a molecular level, to the anti-tumor effects of cisplatin.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins are key cytoplasmic transcription factors. STAT proteins contain multiple domains including a DNA-binding site, Src homology-2 (SH2) domains and a critical tyrosine residue (Y705) situated in the C-terminal domain7. Cytokine and growth factor ligands bind to cell surface receptors resulting in receptor dimerization and transphosphorylation. STAT proteins are recruited to activated cell surface receptors via their SH2 domain and become activated through phosphorylation of the critical Y705 residue by upstream kinases8. In the case of cytokines, such as interleukin-6, whose receptors lack intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, the Janus kinase (JAK) family of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases perform the key STAT-activating phosphorylation step. Transmembrane growth factor receptors such as the epidermal growth factor receptor harbor intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity and are able to phosphorylate STAT independently. Once activated, STAT monomers are able to dimerize through their SH2 domains in a process initiated and stabilized by the key Y705 residue. The activated STAT dimers translocate to the nucleus and bind to specific DNA-response elements in target genes to modulate gene expression7, 9.

The role of STAT proteins in critical cell fate decisions such as cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis, as well as metastasis and immune evasion, makes them attractive targets for anti-tumor therapy7. STAT3 has been shown to be constitutively expressed in HNSCC both in vitro and in vivo10–11. Approximately 82% of HNSCC exhibit up-regulation of STAT3 expression12–13. These findings are likely secondary to the role of STAT3 in oncogenesis. Enhanced STAT3 expression has been correlated with increased anti-apoptotic Bcl-XL protein levels and decreased levels of the pro-apoptotic BAX protein, enhancing HNSCC survival14. STAT3 also induces VEGF expression and, thus, contributes to tumor angiogenesis in HNSCC15. Furthermore, overexpression of cell cycle regulators such as cyclin D1 is induced by STAT3 in HNSCC16–18. STAT3 is known to be constitutively activated in immortalized fibroblasts transformed by oncoproteins such as v-Src. In the absence of STAT3, v-Src is incapable of inducing neoplastic transformation19–20. Overexpression of STAT3 induces tumors in nude mice7.

Interruption of STAT3 signaling has been shown to impede cancer cell growth and to enhance apoptosis in HNSCC11, 21–22. STAT pathway disruption can be achieved at an upstream level through inhibition of JAK2, targeting SH2-mediated dimerization or targeting downstream DNA-binding7. Although significant literature exists regarding the use of STAT inhibitors as a monotherapy for HNSCC, relatively little has been published on the role of STAT inhibition in sensitizing HNSCC to standard treatment regimens. Recently, STAT3 expression has been correlated with cisplatin resistance in HNSCC23. The aim of this study is to determine the role of STAT3 inhibition on sensitization of cancer cells to cisplatin, potentially paving the way for the use of lower, less toxic doses of the drug to achieve an equivalent or enhanced tumor kill.

METHODS

Cell lines

The UMSCC-29 and UMSCC-74B cell lines were originally derived from human head and neck tumor explants, obtained from two patients with advanced HNSCC during surgical resection of the tumor. These patients gave written informed consent in studies reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board. These cell lines were maintained and propagated in our lab. Cell line identity was confirmed through genotyping using a panel of ten different short tandem repeat loci as previously described24. UM-SCC-29 was derived from a primary lesion of the alveolus treated with three courses of neoadjuvant cisplatin and methylglyoxalbisguanylhydrazone (MGBG) followed by surgical resection. UM-SCC-74B was derived from a patient with a persistent tumor of the tongue treated with three cycles of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil in addition to external beam radiotherapy followed by surgical resection. Residual disease resulted in additional treatment with 5-fluorouracil and carboplatin followed by a second surgical extirpation. The UM-SCC-74B cell line is derived from samples obtained at the second surgery. These cell lines have previously been characterized for cisplatin sensitivity25. UM-SCC-10B, UM-SCC-17B and UM-SCC-33 are derived from local recurrence of laryngeal carcinoma, primary laryngeal carcinoma that extended through the cartilage into the soft tissues of the neck, and a paranasal sinus carcinoma, respectively. The ME-180-R cell line is derived from human cervical carcinoma and was made resistant to cisplatin by in vitro selection. The UM-SCC-29 and 74B cell lines were screened for STAT3, phosphorylated STAT3, EGFR, Bcl-XL, survivin, AKT, phosphorylated AKT, SMAC, caspase-3 and p53 expression using Western blot. The cell lines were genotyped to confirm their unique identity. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (cDMEM, Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO) containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 10% fetal bovine serum in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cell lines were tested for mycoplasma using the MycoAlert Detection Kit (Cambrex, Rockland, ME) every 3 to 6 weeks to ensure that they were free of contamination.

Therapeutic reagents

Cisplatin (Cis-diammineplatinum(II) dichloride, DDP) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride to a stock concentration of 3.33mM. Curcumin, a plant-derived chemical, was used as the lead compound to develop a novel SH2(STAT3) inhibitor, termed FLLL3226. Curcumin is known to inhibit multiple molecular pathways including STAT3 but demonstrates poor bioavailability limiting its clinical potential27. FLLL32 is a small molecule inhibitor which specifically targets the SH2 residue of STAT3, and concurrently incorporates improvements in bioavailability for use in biological systems26. FLLL32 was reconstituted in DMSO to a stock concentration of 1 mM. FLLL32 was diluted in cDMEM for all experiments such that the final DMSO concentration in all experiments was less than 1%. Both FLLL32 and cisplatin were stored in dark conditions and experiments were conducted in low-light.

Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) determination

IC50 was derived for both cisplatin and FLLL32 in the UM-SCC-29 and UM-SCC-74B cell lines. For the cisplatin assays, cells were plated at a concentration of 5,000 cells per well in 96 well plates. The cells were incubated overnight in humidified air with 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were treated with serial dilutions of cisplatin (3.125–50μM) or vehicle control for two hours and then reincubated for 5 days. Cell proliferation was quantified using an MTT kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Plates were read using a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 570 nm. Data was analyzed using SigmaPlot 10.0 (SyStat Software, Chicago, IL) to determine IC50. IC50 concentration was also determined for FLLL32. Cells were seeded in 96 well plates at a concentration of 2000 cells/well for UM-SCC-74B and 2500 cells/well for UM-SCC-29 and allowed to incubate overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C. The media was then removed and replaced with cDMEM with 0.2% DMSO or media containing FLLL32 (0.3125 – 5 μM). Cells were incubated for 96 hours and MTT assays performed as above to determine IC50. Experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Western blot

Cells were divided into 4 groups for each cell line: untreated, cisplatin (6.25 μM) alone, FLL at IC50 dose, and FLLL32 at the IC50 dose with cisplatin (6.25μM). Protein was extracted 72 hours post-treatment. Primary antibodies were: rabbit anti-STAT3 monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling, Boston, MA), rabbit anti-Phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705) monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling), mouse anti-JAK2 monoclonal antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA), rabbit anti-phosphorylated JAK2 monoclonal antibody (Millipore), rabbit anti-Bcl-xL monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling) and rabbit anti-EGFR (Cell Signaling). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mouse monoclonal antibody was used as a loading control. The secondary antibody was either horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse antibody (Amersham Life Sciences, Arlington Heights, IL) or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Amersham). Protein bands were observed using the ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection System (Amersham) and visualized on Hyperfilm (Eastman Kodak, Boston, MA). All experiments were repeated in triplicate. ImageJ v. 1.43, a widely used image analysis program publicly available through the NIH, was used for densitometry analysis of protein bands as described in the software documentation.

In vitro FLLL32 effect on cell survival

Cells were divided into 12 groups for each cell line: untreated controls, cisplatin monotherapy (25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.125, 1.5625μM), FLLL32 monotherapy at IC50 dose, and FLLL32 at IC50 dose combined with cisplatin (25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.125, 1.5625μM). UM-SCC-29 and -74B cells were first incubated overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C at seed concentrations of 2500 and 2000 cells/well, respectively, in 96 well plates. FLLL32-containing media was then added into the appropriate treatment groups with all other groups receiving cDMEM with 0.2% DMSO. After a further 24 hours of incubation, cisplatin was added to the appropriate treatment groups at the aforementioned concentrations. Cell survival was then determined after a further 24 and 72 hours incubation by MTT assay as described above.

Apoptosis Assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 60,000 cells/well in 6 well plates for both cell lines and incubated overnight in humidified air with 5% CO2 at 37°C. Each well represented one of the following groups: untreated controls, FLLL32 monotherapy (IC50), Cisplatin monotherapy (1.5625 and 3.125 μM), or FLLL32 (IC50) with cisplatin (1.5625 and 3.125 μM). The FLLL32 was added after the first night of incubation and the cisplatin added the following day. After an additional 48 hours of incubation, cells were resuspended in Annexin V binding buffer (10mM HEPES with 140mM NaCl and 2.5mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) and stained with Annexin V-FITC (Invitrogen) and propidium iodide counterstain. Apoptotic and surviving fraction was then determined by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The two-tailed t-test for independent samples was used for the analysis of all data. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Half-maximal inhibitory concentration determination

A number of HNSCC cell lines were treated with a range of cisplatin doses to determine IC50, including the UM-SCC-29 and UM-SCC-74B cell lines (Figure 1). The UM-SCC-29 cell line demonstrated marked resistance to cisplatin relative to UM-SCC-74B, as evidenced by an IC50 of 12.5μM versus 4.8μM, respectively. These two cell lines were ultimately selected for further experimentation on the basis of their 2.6-fold difference in cisplatin sensitivity, and comparable oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma histology. The IC50 was also determined for FLLL32 in the selected UM-SCC-74B and UM-SCC-29 cell lines (Figure 2). FLLL32 IC50 for the UM-SCC-74B and UM-SCC-29 cell lines were 1.4 and 0.85 μM, respectively.

Figure 1.

MTT chemosensitivity assays were performed for a range of cell lines using a wide range of cisplatin doses. The UM-SCC-29 cell line demonstrates cisplatin resistance (IC50=12.5μM) relative to the cisplatin sensitive UM-SCC-74B cell line (IC50=4.8μM).

Figure 2.

The IC50 for FLLL32 was determined in the UM-SCC-29 and UM-SCC-74B through an MTT chemosensitivity assay. The IC50 for the UM-SCC-74B and UM-SCC-29 cell lines was 1.4 and 0.85 μM, respectively.

Molecular characterization of cell lines

Both UM-SCC-29 and UM-SCC-74B were characterized for the expression of multiple proteins involved in apoptosis (Figure 3). Of importance is the presence of both the wild-type STAT3 protein and the active, phosphorylated variant, pSTAT3, in both cell lines. The phosphorylated variant is though to serve as the target for FLLL32-mediated STAT3 inhibition. The UM-SCC-74B cell line demonstrates less EGFR expression than UM-SCC-29. Expression of p-AKT, the active form of the anti-apoptotic protein AKT1, is also reduced in UM-SCC-74B relative to UM-SCC-29. UM-SCC-74B does not express the tumor suppressor protein, p53, which is consistent with the wild-type p53 gene in this cell line. UM-SCC-29 does have mutant p53 and expresses p53 strongly as expected for the mutant protein. The anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-xL and survivin are expressed in both cell lines, as are the pro-apoptotic proteins SMAC and caspase 3. Beta actin control showed equal loading between cell lines.

Figure 3.

UM-SCC-74B and UM-SCC-29 cells were characterized for STAT3 and p-STAT3 expression, as well as anti-apoptotic proteins (AKT1, p-AKT1, Bcl-xL, survivin) and pro-apoptotic proteins (SMAC, caspase-3) involved in the JAK-STAT pathway. Expression of EGFR, an upstream STAT3 activator, and p53 was determined.

FLLL32 mediates down-regulation of phosphorylated STAT3 expression

Phosphorylated STAT3 is the active from of the STAT3 protein. To determine whether FLLL32 is effective in down-regulating phosphorylated STAT3 protein, a Western blot was performed incorporating cells subject to no treatment, cisplatin alone, cisplatin with FLLL32 and FLLL32 alone (Figure 4). Densitometry analysis demonstrated a significant down-regulation of pSTAT3 protein following treatment with FLLL32 versus non-treatment controls (p<0.05). This down-regulation was not observed in cells that were treated with cisplatin alone. FLLL32 had no effect on the expression of STAT3, JAK2, Bcl-xL, EGFR or GAPDH protein, the latter of which was used as an internal positive control. Phosphorylated JAK2 protein could not be detected in either cell line.

Figure 4.

Western blot demonstrates a down-regulation of phosphorylated STAT3 in the UM-SCC-29 and -74B cell lines following administration of FLLL32, with or without cisplatin. The expression level of non-phosphorylated, inactive STAT3 remains unchanged in both cell lines after the addition of FLLL32 or cisplatin, alone or in combination. JAK2 and non-phosphorylated STAT3 expression was stable across cell lines and treatment groups. Phosphorylated JAK2 protein (not shown) could not be isolated. FLLL32, with or without cisplatin, did not alter the expression of the pro-apoptotic proteins Bcl-xL or AKT or of the upstream signaling molecule EGFR. GAPDH was used as a positive loading control.

FLLL32 is cytotoxic to HNSCC cells as a monotherapy and enhances the cytotoxicity of cisplatin in vitro

MTT cell survival assays were performed to assess the cytotoxic effect of FLLL32, alone and in combination with a range of cisplatin doses, on HNSCC cells from both cell lines (Figure 5). In the UM-SCC-74B cell line, the percentage of viable cells relative to untreated control was 73, 56, 34, 22 and 16% for the cisplatin monotherapy groups at doses of 1.5625 – 12.5 μM. Combining FLLL32 at the IC50 dose with cisplatin at doses of 1.5625 – 12.5 μM resulted in a relative cell viability compared to controls of 35, 29, 23, 17 and 15%, respectively. Monotherapy with FLLL32 resulted in 39% cell survival versus untreated controls. Comparison between treatment groups was statistically significant (p<0.0001–0.05) for all groups except FLLL32 with cisplatin (25μM) versus cisplatin (25μM), FLLL32 with cisplatin (6.25μM) versus cisplatin (12.5μM), and FLL with cisplatin (1.56μM) versus cisplatin (6.25μM). FLLL32 with cisplatin (1.5625μM) induced a 38% reduction in cell viability versus cisplatin monotherapy (1.5625μM, p<0.001). In UM-SCC-74B cells, FLLL32 with cisplatin (1.5625μM) induced equivalent tumor cytotoxicity to cisplatin given alone at a four-fold higher dose (6.25μM).

Figure 5.

In UM-SCC-74B cells, which are relatively cisplatin sensitive, combination therapy with FLLL32 and cisplatin (1.5625μM) induced an equivalent cytotoxic effect to cisplatin monotherapy at a dose four times higher (6.25μM) and enhanced cytotoxicity versus cisplatin monotherapy at doses of 1.5625 – 3.25 μM (p<0.001). The same effect was observed in cisplatin resistant UM-SCC-29 cells. This suggests that FLLL32 can induce sensitivity in HNSCC cells and that this effect is not compromised by intrinsic resistance to cisplatin.

In the UM-SCC-29 cell line, cell viability relative to untreated controls was 84, 61, 41, 26 and 18% for the cisplatin monotherapy groups at doses of 1.5625 – 12.5 μM. Combination therapy with FLLL32 at the IC50 dose and cisplatin at doses of 1.5625 – 12.5 μM induced a relative cell survival of 40, 35, 26, 21 and 16%, respectively, versus control. Monotherapy with FLLL32 alone resulted in 48% cell survival versus control. Comparisons between treatment groups was statistically significant (p<0.0001–0.02) for all groups with the exception of FLLL32 with cisplatin (6.25μM) versus cisplatin (12.5μM), and FLLL32 with cisplatin (1.56μM) versus cisplatin (6.25μM). FLLL32 with cisplatin (1.5625μM) induces a 44% reduction in cell viability versus cisplatin monotherapy (1.5625μM, p<0.001). The key finding was that combination therapy with FLLL32 and cisplatin (1.5625μM) induced a suppressive effect comparable to cisplatin monotherapy at 6.25 μM and an enhanced cytotoxic effect versus cisplatin monotherapy at doses of 1.5625 – 3.25 μM (p<0.01) in cisplatin-resistant UM-SCC-29 cells.

These findings suggest that FLLL32 sensitizes both cisplatin sensitive cells and, critically, intrinsically cisplatin resistant UM-SCC-29 HNSCC cells to treatment with low concentrations of cisplatin. FLLL32 effectively permits the use of up to a four-fold lower dose of cisplatin than used in cisplatin monotherapy while achieving comparable or enhanced inhibition of tumor cell survival.

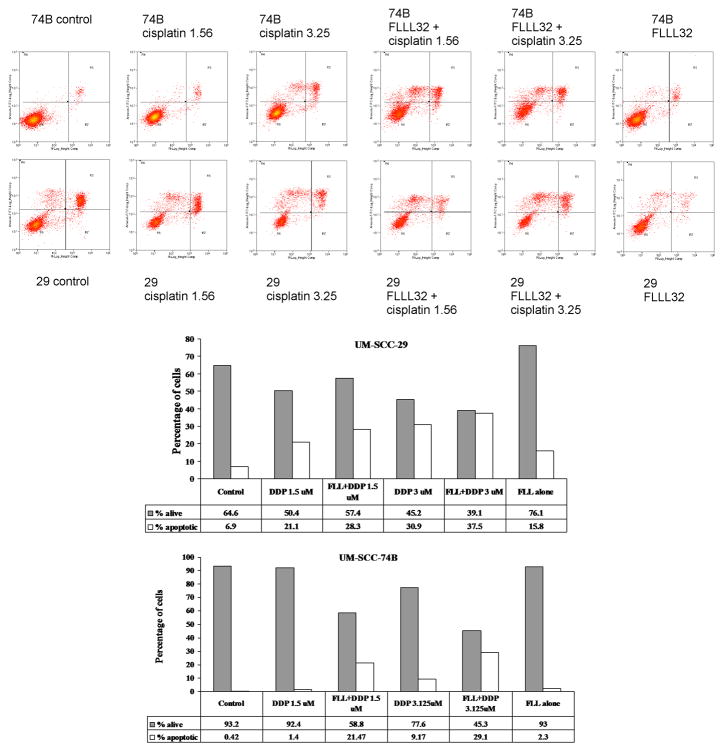

FLLL32 potentiates apoptosis in HNSCC cells

To further investigate the mechanism of FLLL32 cytotoxicity in HNSCC cells, as well as to elucidate potential underlying mechanisms for the enhancement of FLLL32 efficacy through combination therapy with cisplatin, apoptosis was evaluated using flow cytometry (Figure 6). As expected, untreated cells had low levels of apoptosis of 0.42% and 6.94% for the UM-SCC-74B and -29 cell lines, respectively. FLLL32 alone resulted in a modest increase in the proportion of apoptotic cells to 2.29% and 15.82% for the UM-SCC-74B and -29 cell lines, respectively. FLLL32 combination treatment with cisplatin (3.125μM) decreased the proportion of living cells to 45.34 and 39.06% and increased the percentage of apoptotic cells to 29.10 and 37.52% in UM-SCC-74B and -29, respectively. The effect was similar but reduced when FLLL32 was combined with a lower dose of cisplatin (1.5625μM). This represents a significant improvement over the extent of apoptosis induced by cisplatin monotherapy alone at either 1.5625 or 3.125 μM doses. These data indicate that FLLL32 can potentiate apoptosis induced by cisplatin in both cisplatin resistant and sensitive cell lines.

Figure 6.

FLLL32 alone induced an increase in apoptosis in UM-SCC-74B and -29. The combination of FLLL32 and cisplatin induces greater apoptosis than either agent alone. Interestingly, the cisplatin resistant UM-SCC-29 cell line exhibited greater increases in apoptosis than UM-SCC-74B in all treatment groups. Data is shown as apoptosis flow cytometry plots (y-axis: logarithmic quantification of annexin V-FITC positive cells; x-axis: logarithmic quantification of propidium iodide positive cells), and as bar graphs with data tables.

DISCUSSION

Platinum-based compounds are often used as first-line agents in the treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cisplatin exerts a dose-dependent effect such that higher doses induce apoptosis in a larger fraction of tumor cells28. The effectiveness of cisplatin is tempered by the development of enhanced DNA damage repair mechanisms in treated cancer cells such that they are able to escape apoptosis-inducing damage5. Clinically, this necessitates the use of increasing doses of cisplatin and a significant increase in treatment-limiting toxicity29. Those who survive treatment of their initial cancer often suffer long-term treatment-related morbidity and will often succumb to distant metastases. This is the underlying cause of the 5 year overall survival rate of approximately 50% and the lack of improvement in survival statistics over the past several decades.

Consequently, significant research efforts have been directed towards understanding the molecular changes which underlie HNSCC, targeting these mechanisms and either directly inducing cancer cell death or disrupting pathways that permit the survival of cancers subject to standard therapeutic approaches. One such molecular target is the JAK/STAT pathway which is overexpressed in 82% of HNSCC12–13. The JAK/STAT3 pathway has been shown to drive HNSCC independent of growth factors such as EGFR17. Disruption of STAT3 signaling has been shown to be effective in a range of solid tumors including HNSCC7, 10–11, 21, 26, 30–31.

The current study investigates the role of FLLL32, a curcumin-based STAT3 inhibitor, on HNSCC cells in vitro in terms of efficacy as a monotherapy and as a means of sensitizing cancer cells to cisplatin. FLLL32 is specifically designed to inhibit STAT3 through blockade of the SH2 dimerization site26. Consistent with a recently published report that used FLLL32 in breast and pancreatic cancer, we found that FLLL32 appears to be selective for the JAK/STAT pathway by downregulating activated STAT3 expression in HNSCC26.

FLLL32 is able to induce a significant anti-tumor effect when used as a monotherapy in both cisplatin sensitive and cisplatin resistant cell lines. More importantly, FLLL32 induces a potent chemosensitization effect even in cisplatin-resistant HNSCC cells, permitting the use of cisplatin doses several fold lower than used in cisplatin monotherapy while achieving an equivalent tumor inhibition. Our data indicate that this is partially attributable to an increase in the proportion of apoptotic cells and a decrease in surviving fraction in HNSCC cells treated with FLLL32 and cisplatin in combination.

Translating these findings to the clinical realm will require further investigation. In particular, further studies will need to elucidate whether the observed in vitro chemosensitization effect is translatable to animal models of HNSCC. Additionally, the absence of dose-limiting toxicity seen with curcumin, the compound on which FLLL32 is based, suggests that STAT3 inhibitors may have a clinical role in the future31–32. Continued investigation of the JAK/STAT pathway and the design of novel inhibitors, like FLLL32, that are capable of targeting this pathway may herald new therapeutic approaches that enhance or obviate the need for currently used chemotherapeutic agents.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH NIDCR 1 R01-DE019126, NIH NCI Head and Neck SPORE 1 P50 CA97248, NIH NCI through the University of Michigan’s Cancer Center Support Grant (5 P30 CA46592), NIH-NIDCD T32 DC05356, and NIH NIDCD P30 DC-05188. Additional funding was through an American Cancer Society grant (#IRG-67-003-44) to J.R.F.

WMA and TEC had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Presentations: This work was presented as a podium presentation at the American Head & Neck Society Annual Meeting 2010, Las Vegas, NV, on April 28th, 2010.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelland L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007 Aug;7(8):573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs C, Lyman G, Velez-Garcia E, et al. A phase III randomized study comparing cisplatin and fluorouracil as single agents and in combination for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(2):257–263. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vokes EE, Athanasiadis I. Chemotherapy of squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck: the future is now. Ann Oncol. 1996;7(1):15–29. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu G. Cellular responses to cisplatin. The roles of DNA-binding proteins and DNA repair. J Biol Chem. 1994 Jan 14;269(2):787–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez RP. Cellular and molecular determinants of cisplatin resistance. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(10):1535–1542. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jing N, Tweardy DJ. Targeting Stat3 in cancer therapy. Anticancer Drugs. 2005 Jul;16(6):601–607. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darnell JE., Jr STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997 Sep 12;277(5332):1630–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowman T, Garcia R, Turkson J, Jove R. STATs in oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2000 May 15;19(21):2474–2488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grandis JR, Drenning SD, Zeng Q, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 signaling abrogates apoptosis in squamous cell carcinogenesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Apr 11;97(8):4227–4232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song JI, Grandis JR. STAT signaling in head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 2000 May 15;19(21):2489–2495. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagpal JK, Mishra R, Das BR. Activation of Stat-3 as one of the early events in tobacco chewing-mediated oral carcinogenesis. Cancer. 2002 May 1;94(9):2393–2400. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu B, Ren Z, Shi Y, Guan C, Pan Z, Zong Z. Activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 and overexpression of its target gene CyclinD1 in laryngeal carcinomas. Laryngoscope. 2008 Nov;118(11):1976–1980. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817fd3fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee TL, Yeh J, Friedman J, et al. A signal network involving coactivated NF-kappaB and STAT3 and altered p53 modulates BAX/BCL-XL expression and promotes cell survival of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2008 May 1;122(9):1987–1998. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masuda M, Ruan HY, Ito A, et al. Signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 up-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor production and tumor angiogenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2007 Sep;43(8):785–790. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buettner R, Mora LB, Jove R. Activated STAT signaling in human tumors provides novel molecular targets for therapeutic intervention. Clin Cancer Res. 2002 Apr;8(4):945–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kijima T, Niwa H, Steinman RA, et al. STAT3 activation abrogates growth factor dependence and contributes to head and neck squamous cell carcinoma tumor growth in vivo. Cell Growth Differ. 2002 Aug;13(8):355–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masuda M, Suzui M, Yasumatu R, et al. Constitutive activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 correlates with cyclin D1 overexpression and may provide a novel prognostic marker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002 Jun 15;62(12):3351–3355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu CL, Meyer DJ, Campbell GS, et al. Enhanced DNA-binding activity of a Stat3-related protein in cells transformed by the Src oncoprotein. Science. 1995 Jul 7;269(5220):81–83. doi: 10.1126/science.7541555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bromberg JF, Horvath CM, Besser D, Lathem WW, Darnell JE., Jr Stat3 activation is required for cellular transformation by v-src. Mol Cell Biol. 1998 May;18(5):2553–2558. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leeman-Neill RJ, Wheeler SE, Singh SV, et al. Guggulsterone enhances head and neck cancer therapies via inhibition of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3. Carcinogenesis. 2009 Nov;30(11):1848–1856. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kupferman ME, Jayakumar A, Zhou G, et al. Therapeutic suppression of constitutive and inducible JAK\STAT activation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2009;8(2):117–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu F, Ma Y, Zhang Z, et al. Expression of Stat3 and Notch1 is associated with cisplatin resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2010 Mar;23(3):671–676. doi: 10.3892/or_00000683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenner JC, Graham MP, Kumar B, et al. Genotyping of 73 UM-SCC head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Head Neck. 2010 Apr;32(4):417–426. doi: 10.1002/hed.21198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradford CR, Zhu S, Ogawa H, et al. P53 mutation correlates with cisplatin sensitivity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma lines. Head Neck. 2003 Aug;25(8):654–661. doi: 10.1002/hed.10274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin L, Hutzen B, Zuo M, et al. Novel STAT3 phosphorylation inhibitors exhibit potent growth-suppressive activity in pancreatic and breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010 Mar 15;70(6):2445–2454. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aggarwal BB, Sung B. Pharmacological basis for the role of curcumin in chronic diseases: an age-old spicewith modern targets. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009 Feb;30(2):85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorenson CM, Eastman A. Mechanism of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)-induced cytotoxicity: role of G2 arrest and DNA double-strand breaks. Cancer Res. 1988 Aug 15;48(16):4484–4488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, et al. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004 May 6;350(19):1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darnell JE., Jr Transcription factors as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002 Oct;2(10):740–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chakravarti N, Myers JN, Aggarwal BB. Targeting constitutive and interleukin-6-inducible signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells by curcumin (diferuloylmethane) Int J Cancer. 2006 Sep 15;119(6):1268–1275. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatcher H, Planalp R, Cho J, Torti FM, Torti SV. Curcumin: from ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008 Jun;65(11):1631–1652. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]