Abstract

Objective. To assess the impact of pharmacy students teaching a diabetes self-management education (DSME) class on their competence and confidence in providing diabetes education.

Design. Pharmacy students enrolled in a service-learning elective first observed pharmacy faculty members teaching a DSME class and then 4 weeks later organized and taught a DSME class to a different group of patients at a student-run free medical clinic.

Assessment. Student performance as assessed by faculty members using a rubric was above average, with a mean score of 3.3 on a 4.0 scale. Overall, student confidence after teaching the group DSME class was significantly higher than before teaching the class.

Conclusion. Organizing and teaching a DSME class improved third-year pharmacy students’ confidence and diabetes knowledge and skills, as well as provided a valuable service to patients at a free medical clinic.

Keywords: diabetes education, diabetes, pharmacy students, service-learning

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes self-management education (DSME) is an ongoing process of teaching patients the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary for diabetes self-care.1 The clinical practice recommendations of the American Diabetes Association state that all clinical practitioners should recommend DSME to their patients with diabetes.2 Currently, there is no required format for providing DSME. However, approaches to diabetes education that are interactive and patient-centered have been associated with positive patient outcomes. Many educational tools and curricula exist such as the US Diabetes Conversation Map Program.3 Conversation maps are interactive educational tools used to guide provider-patient conversations. One or more of the instructors who facilitate DSME should be a registered nurse, dietician, or pharmacist.1 Pharmacists can have an integral role in diabetes education, and exposing pharmacy students to opportunities to educate diabetes patients and use educational tools within the pharmacy curriculum may prepare students to provide DSME to patients.

A variety of active-learning educational techniques such as use of diabetes simulations, as well as elective courses and certificate programs, have been used to improve pharmacy students’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills related to diabetes.4-8 However, there are no published reports of group DSME classes facilitated by pharmacy students. A review of the literature revealed a single study that involved nursing student-facilitated DSME group classes using diabetes conversation maps. However, the study did not incorporate actual patients; rather some students role-played patients with diabetes while other students taught the DSME class. Participation in this exercise increased nursing student knowledge about diabetes and patient education techniques.9

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) encourages the use of actual patients in active-learning exercises according to Standard 11.10 In addition, the Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) outcomes highlight the importance of using actual patients when pharmacy students provide pharmaceutical care.11 Group DSME classes for actual patients taught by pharmacy students fulfill these curricular standards and outcomes for active learning.

An assignment that involved organizing and teaching a group DSME class to patients at a free medical clinic was developed for third-year students at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) campus of the South Carolina College of Pharmacy and integrated into the curriculum of an elective service-learning course offered to health professions students at MUSC. The objectives of the study were to (1) determine the effect of organizing and teaching a group DSME class on pharmacy student confidence regarding DSME knowledge and skills and (2) assess pharmacy students’ abilities to provide group DSME classes.

DESIGN

An interprofessional service-learning elective was offered to medical, physician assistant, physical therapy, and pharmacy students at MUSC in the fall and spring semesters. The course was team-taught by faculty members in the colleges of medicine and pharmacy. During the elective, students provided care to patients at a student-run free medical clinic and attended weekly class lectures. All students were provided grades for the elective course on a pass/fail scale. Teaching the group DSME classes for patients at the clinic was an additional assignment specifically for third-year pharmacy students enrolled in the elective.12

Incorporation of a group DSME class in the curriculum of a service-learning elective required the integration of diabetes and DSME knowledge, patient communication, and problem-solving skills. Organizing and teaching the DSME classes fulfilled specific ACPE accreditation standards and CAPE outcomes, while incorporating active learning into the curriculum through use of actual patients and emphasis on andragogy (adult-learning techniques). Specific learning objectives for the group DSME class assignment included: (1) provide DSME to patients; (2) demonstrate appropriate patient education and counseling skills; (3) demonstrate appropriate education, facilitation, and communication skills when working with groups of patients; (4) increase student confidence in diabetes knowledge, DSME, and group patient education and facilitation skills.

The 23 third-year pharmacy students who completed the course had previously completed diabetes modules in the pharmacotherapy course, clinical assessment, and community practice laboratory courses. The students were asked to prepare for teaching the DSME class on their own time. Preparation time for each student varied depending on their comfort level and knowledge base; on average, students prepared for 1 hour prior to the class. The 2-hour DSME class was offered twice per semester to patients at the student-run free medical clinic. Patients were referred to the class by the students who saw them in the free medical clinic. Approximately 5 to 10 patients attended each class. The US Diabetes Conversation Map titled “Overview of Diabetes” was used in the class.

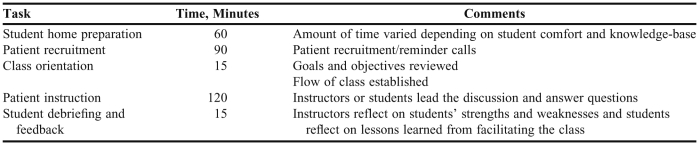

The first DSME class each semester was taught by 2 pharmacy faculty members who were certified diabetes educators, while the second class was taught by the students (Table1). An hour prior to the first DSME class, the 2 pharmacy faculty members held an informal educational session in which the pharmacy students were given information on the benefits of DSME and a copy of the conversation map and then helped faculty members set up for the class. The faculty members then taught the DSME class to patients while the pharmacy students observed. After the class, the pharmacy students and faculty members discussed observations and highlighted important DSME knowledge, patient education, and group facilitation skills.

Table 1.

Logistics and Delivery of a Diabetes Self-Management Education Class Taught by Third-Year Pharmacy Students

For the second DSME class, each pharmacy student was assigned a specific section of the conversation map to lead, but they were expected to know how to facilitate all of the DSME concepts and help with the entire class. The second class of the semester was held 1 month after the first. Faculty members were available to clarify points missed by the students, but their main role was support and student evaluation. After the second class was completed, the faculty members engaged the students in a discussion, including self-reflection on their performance and important lessons learned.

Establishment of the group DSME class at the student-run free medical clinic initially required a large time commitment of the 2 pharmacy faculty members. The medical students operating the clinic had to be educated about the benefits of DSME and the ability of pharmacists and pharmacy students to provide this education. Once the diabetes classes were established, required faculty time decreased to 8 hours per semester. The majority of faculty time was allocated to attending the classes, educating the students, and providing feedback and formal evaluation.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

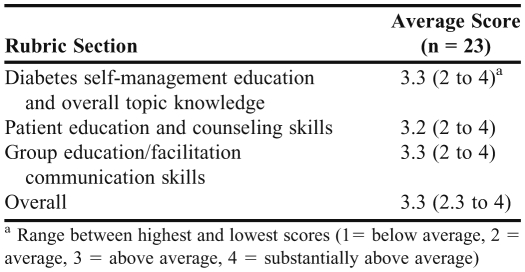

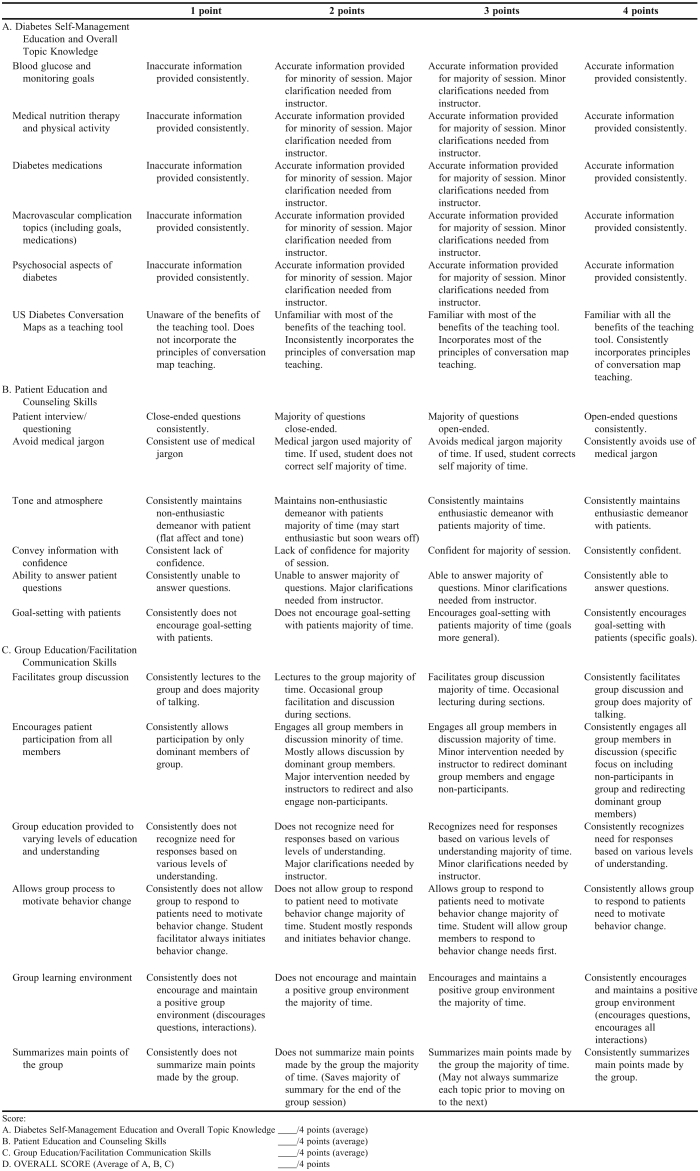

The group DSME class organized and taught by pharmacy students was evaluated using 2 methods, a rubric and a questionnaire to assess the specific learning objectives for the assignment. Because a rubric that could be adapted for assessing student-performance in teaching a DSME class could not be found in the literature, the authors developed their own. Feedback on the rubric was provided by other certified diabetes educators and incorporated into the final version. The rubric evaluated 3 principles: (1) overall DSME topic knowledge (eg, blood glucose monitoring, diabetes medication, and medical nutrition therapy), (2) patient education and counseling skills, and (3) group facilitation and communication skills. The rubric was based on a 4-point evaluation system (with 1 point being the low score and 4 points being the high score); each students’ performance was assessed using each section of the rubric and then an overall score was determined.

Twenty-three pharmacy students taught the group DSME classes over the course of 5 semesters. The students’ mean score was 3.3 points out of 4 points (range 2.3 to 4.0) (Table 2). The evaluations were provided to each student for learning purposes but were not used in determining the students’ course grade (Appendix 1).

Table 2.

Evaluation of Pharmacy Students Teaching a Diabetes Self-Management Education Class

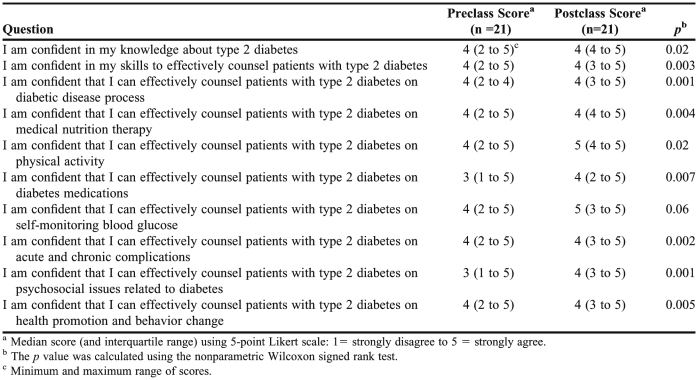

In addition to the evaluation using the rubric, students’ confidence in their DSME knowledge and skills was assessed before and after facilitating the class using a 10-question survey instrument that was developed by the authors, reviewed by other certified diabetes educators, and revised based on their feedback. Item responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Students completed the voluntary and anonymous survey instrument via SurveyMonkey, Inc. (Palo Alto, CA). The survey instrument was administered during the first week of the elective prior to any patient care experience at the clinic and again 1 week after the students taught the group DSME class. The students were provided an anonymous code to enter on the survey instrument so the responses collected before and after teaching the DSME class could be paired.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.2 (Cary, NC). Student performance based on rubric scores was analyzed using descriptive statistics. Student confidence comparing results before and after teaching the DSME class was analyzed using the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. This study was approved as exempt research by the university's institutional review board.

Twenty-one students (91%) completed the survey instrument. Student confidence significantly increased in 9 out of 10 of the areas surveyed: diabetes knowledge, counseling skills, diabetes disease process, medical nutrition therapy, physical activity, diabetes medications, acute and chronic diabetes complications, psychosocial diabetes issues, health promotion, and behavior change.

DISCUSSION

The value of incorporating diabetes simulations into the pharmacy curriculum has been demonstrated, but we present the first description and evaluation of pharmacy student-taught DSME classes.7,8 The incorporation of the DSME classes into the service-learning elective had a significant impact on student confidence in their DSME knowledge and skills. In addition, student performance in organizing and teaching the DSME classes was above average.

This description of pharmacy students teaching DSME classes at a student-run free medical clinic adds to the current literature as it is a novel educational approach that incorporates active-learning using actual patients rather than just providing descriptions of patient cases. This study evaluated student performance in teaching DSME classes and assessed student confidence before and after the exercise. The educational design fulfilled ACPE educational standards and CAPE outcomes for active learning. This experience allowed the students to apply what they have learned about diabetes in the classroom setting to real patients at the clinic. The small group setting allowed numerous opportunities for communication between students and patients. This experience also was beneficial as it added a pharmacy-specific role for the students at the clinic and allowed the students to be more involved in patient care.

Through this experience, student confidence improved in 9 out of the 10 areas examined. Specific areas, such as confidence in patient counseling, significantly benefited from this exercise; students developed skills in providing patient education to a group of patients, which can be challenging. Another area that improved dramatically was students’ confidence in their knowledge of type 2 diabetes. Requiring students to prepare to teach a diabetes education class encouraged them to become knowledgeable in all areas of diabetes. This approach to learning is based on the theory that to effectively teach another, one must first become competent in the topic themselves. We feel that this experience was valuable to all involved and allowed the students to have more direct patient care experience prior to beginning their fourth-year advanced pharmacy practice experiences.

While our study adds to the literature, it is not without limitations. This study assessed student confidence and performance in organizing and teaching DSME classes; however, one area that was not assessed was knowledge. Having the students complete a quiz before and after teaching the DSME class would have improved the assessment methods. In addition, when assessing changes in student confidence, there were not significant changes in certain areas (Table 3). This may limit the academic significance of the results.

Table 3.

Pharmacy Students Confidence Regarding Knowledge and Delivery of Diabetes Self-Management Education

Another potential limitation was the lack of standardization of the DSME classes. While the same conversation map was used for all classes, the focus of the discussion varied depending on the needs of the patients involved. Some classes may have concentrated more heavily on one area, such as nutrition and less in another, such as medication education. This lack of standardization did provide external validity, as it is difficult to control patient attendance and interest in participation in a DSME class regardless of who is teaching it. Surveying patient satisfaction with the student-facilitated classes would have added to the experience. A patient survey could have provided vital feedback to improve the quality of the classes.

Another limitation included the amount of faculty time necessary to provide this experience to the students. The classes were only offered twice a semester, however, a significant amount of time was spent on patient recruitment, set-up, and class planning. Because there were other health professions students at the clinic, it would have been beneficial to incorporate them into this experience. Facilitating the classes at a student-run free medical clinic and through an elective course posed challenges. It was difficult for some patients to get transportation to and from the clinic and the elective was not offered during the summer. These factors limited the number of DSME classes that could be offered each year.

SUMMARY

A diabetes self-management education class taught by third-year pharmacy students at a student-run free medical clinic was incorporated into an existing service-learning elective as an active-learning activity. Student self-assessed confidence regarding DSME knowledge and skills increased significantly and student performance as assessed using a rubric evaluation tool was satisfactory. The course proved beneficial to patients at the clinic as well as pharmacy students. Pharmacy educators at other colleges and schools could offer a similar DSME experience.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This project was supported by the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute, Medical University of South Carolina's CTSA, NIH/NCRR Grant Number UL1RR029882. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NCRR.

Appendix 1. Group Diabetes Education Class Facilitation Evaluation Rubric

Student Name: Date:

REFERENCES

- 1.Funnell MM, Brown TL, Childs BP, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S89–S96. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes- 2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S11–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The US Diabetes Conversation Map Program. http://www.healthyinteractions.com/conversation-map-programs/conversation-map-experience/current-programs/usdiabetes. Accessed January 5, 2012.

- 4.Johnson JF, Chesnut RJ, Tice BP. An advanced diabetes care course as a component of a diabetes concentration. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(1):Article 21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odegard PS, LaVigne LL, Ellsworth A. A diabetes education program for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66(4):391–395. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan GJ, Foster KT, Unterwagner W, Jia H. Impact of a diabetes certificate program on PharmD students’ knowledge and skills. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(5):Article 88. doi: 10.5688/aj710584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westburg SM, Bumgardner MA, Brown MC, Frueh J. Impact of an elective diabetes course on student pharmacists’ skills and attitudes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(3):Article 49. doi: 10.5688/aj740349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delea D, Shrader S, Phillips C. A week-long diabetes simulation for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(7):Article 130. doi: 10.5688/aj7407130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strang SL, Bagnardi M, Williams Utz S. Tailoring a diabetes nursing elective course to millennial students. J Nurs Educ. 2010;49(12):684–686. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20100831-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2012.

- 11.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Documents/CAPE2004.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2012.

- 12.Shrader S, Thompson A, Gonsalves W. Assessing student attitudes as a result of participating in an interprofessional healthcare elective associated with a student-run free clinic. J Res Interprofessional Pract Educ. 2010;1(3):218–230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]