Abstract

This paper describes the faculty enrichment activities and outcomes of a faculty orientation and development committee at a college of pharmacy. The committee used a continuous quality improvement (CQI) framework that included needs assessment, planning and implementation of programs and workshops, assessment of activities, and evaluation of feedback to improve future programming. Some of the programs established by the committee include a 3-month orientation process for new hires and development workshops on a broad range of topics including scholarship (eg, research methods), teaching (eg, test-item writing), and general development (mentorship). Evidence of the committee's success is reflected by high levels of faculty attendance at workshops, positive feedback on workshop evaluations, and overall high levels of satisfaction with activities. The committee has served as a role model for improving faculty orientation and retention.

Keywords: faculty, faculty retention, faculty orientation, faculty development

INTRODUCTION

Faculty recruitment and retention in colleges and schools of pharmacy have received significant attention in the last decade.1 Three hundred ninety-six faculty positions were vacant or lost from 101 colleges and schools of pharmacy in 2008-2009, with the top 3 reasons cited as: “individual in position moved to a faculty position at another pharmacy college or school (20.1%); individual moved to a practice position in the health care private sector (15.4%); and individual in the position retired (12.6%).”2

Pharmacists are in great demand in multiple practice settings, and this has created a direct challenge in attracting faculty members who are persistently courted by pharmacy chain store corporations, independent pharmacies, and the pharmaceutical industry, all of which offer better compensation packets.3 Similarly, attempts to enlist postdoctoral residents and fellows or graduate students into academia are not always met with success because of competing recruitment from high-compensating clinical or industry positions. Another challenge to recruitment is the multifaceted demands of academia, ie, teaching, scholarship, and service. Moreover, in the area of pharmacy practice, in which there is a greater number of vacancies, there is the additional burden for faculty members to balance provision of clinical service with academic responsibilities.2

In addition to competition from recruiters outside of academia, competition for faculty members among institutions also has intensified as a result of the increase in the number of colleges and schools of pharmacy in the last decade.4,5 These challenges have resulted in colleges and schools hiring faculty members who recently completed their postdoctoral training and have minimal academic experience. These trends makes it imperative to have faculty development and mentorship programs that can help maintain the quality of educational programs and retain these junior faculty members.6,7 Moreover, faculty members at existing colleges and schools of pharmacy are often recruited by newer colleges and schools to fill faculty or administrative positions, sometimes at a level incongruent with their academic experience.

The loss of a faculty member has multiplicative negative effects. The economic cost of losing one faculty member equates to approximately 1.5 times the faculty member's salary when the time and effort spent in hiring, training, and mentoring a replacement are calculated. Other adverse effects are the loss of the professional networks developed by an experienced faculty member and the loss of university revenue streams via grants transferred. Conversely large dividends may be realized if colleges and schools of pharmacy invest resources into faculty recruitment, enrichment, and retention.

In an attempt to standardize faculty orientation, enhance faculty development, and ultimately influence recruitment and retention, the College of Pharmacy at Western University of Health Sciences established a committee to focus on these issues. In 1998, after the college had been in existence for 2 years, the Faculty Orientation, Evaluation, and Development Committee was instituted to address development of faculty members. However, with the maturation of the college over the years and the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education's requirement that pharmacy institutions conduct assessment activities, the college shifted assessment and evaluation functions to a separate committee. Thus, in 2006, the Faculty Orientation, Evaluation, and Development Committee was renamed the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee and began focusing its effort strictly on orientation and development.

The purpose of this article is to describe the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee and the faculty development programs that it has successfully implemented at our institution. We present a simple continuous quality improvement (CQI) model that can be replicated and transferred to other settings.

Committee Design and Function

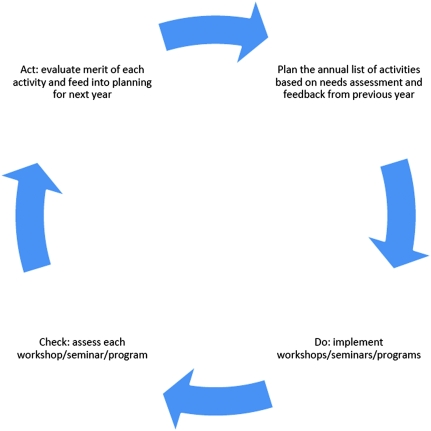

The purpose of the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee is to conduct the orientation process for new faculty members and coordinate all aspects of faculty development programs, including their identification, design, and execution. To ensure their effectiveness, the committee also assesses and evaluates these programs via participant feedback, using the CQI model Plan, Do, Check, Act (Figure 1).8 The committee is substantially integrated with the college's curriculum and assessment committees to synergize the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee's purpose and programs. For example, ideas related to faculty development that are generated through discussions at curriculum committee meetings can be proposed to the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee and result in the offering/creation of workshops, such as writing effective test questions, evidence-based medicine, and implementation of active-learning methods. The committee also collaborates with the assessment committee to develop program evaluations and CQI processes. Representation of the curriculum and assessment committees (ie, ex officio members) on the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee ensures optimal communication and efficient functioning.

Figure 1.

The continuous quality improvement model Plan, Do, Check, Act used by the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee.

As directed by the bylaws of the college, the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee consists of a minimum of 5 faculty members with at least 2 members from the Pharmaceutical Sciences department and 2 from the Pharmacy Practice & Administration department. The Associate Dean for Academic and Student Affairs and department chairs serve as ex officio members as faculty development is one of their key functions. In addition, there is representation from the Center for Academic Performance and Enhancement, which is the university body that oversees faculty development. Faculty members’ usually serve on the committee for 2 years with staggered terms to ensure continuity. A chair and vice chair for the committee are annually elected from among the faculty members serving on the committee. The vice chair presides in the absence of the chair and in most cases, is elected to chair the subsequent year.

Each committee initiative is based on a CQI process model, as mentioned above.8,9 Ideas are generated through a needs assessment survey of faculty members conducted every 2 years by the Center for Academic Performance and Enhancement as well as from college administration and other committees in the college. In the plan stage of the Plan, Do, Check, Act model, the committee discusses the relevance of each idea and possible programs that could be pursued and their priority, as well as possible dates and availability of presenters. Participation in programs and workshops is extended to all faculty members in the college. Programs and workshops are usually conducted during breakfast or lunch hours, with a meal provided to optimize attendance and encourage professional socialization. The Faculty Oritentation and Development Committee either develops assessment tools and outcome evaluation processes itself or does so in conjunction with the assessment committee. As part of the check stage of CQI, anonymous survey instruments are administered at the end of each workshop session to assess program content and speakers, and to obtain constructive feedback. Results are collated by the committee and used to improve future programs. An overall survey of faculty satisfaction with the committee's activities is also conducted periodically.10,11

Faculty Oritentation and Development Committee Programs

The primary function of the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee is to develop programs that fit in 1 of 3 main categories: faculty orientation, faculty development, and longitudinal faculty development.

Faculty Orientation. Activities related to faculty orientation begin even before a faculty member starts work at the college. The committee's philosophy of orientation is based on the understanding that a meaningful, well-planned orientation ensures a smooth transition into the college for new hires, helps engage them more quickly in their work responsibilities and the affairs of the college, and prevents frustrations that may occur from lack of understanding about the culture of the organization, including its processes and expectations.10

The initial orientation program evolved from a logistics-based approach to one based on a framework of the needs required to be addressed in any transition (ie, personnel, procedures, and policies). The major component of the current orientation program involves meeting with all administrators within the college and relevant university departments (Office of Grants and Contracts, Information Technology, etc). The process ensures that each new faculty member receives essential information (such as organizational issues and teaching modalities), crucial documents (promotion and tenure, committees), and curriculum-relevant materials (Blackboard and teaching technology training).

As initiating employment can be a stressful time in which the faculty member is inundated with new information, the committee created an orientation flowchart (FOD Orientation Flowchart) and orientation booklet that each new faculty member receives. These tools provide a structured framework for the orientation process and facilitate retention of important information across changing committee membership. The booklet details key points for discussion, lists meeting names and dates, and provides a space for the orientation coordinator to sign indicating the meeting has been held. Each new faculty member is also assigned to a point person or “go-to” faculty member from the same department who arranges a lunch meeting with new faculty colleagues and works to facilitate the socialization of the new hire within the department. New faculty members are also assigned a staff support person who helps with scheduling orientation meetings and addresses the new faculty member's questions and concerns. (Each year, the support staff members in the college undergo a 1-hour refresher training course on the faculty orientation process.) After completion of the orientation process, which generally takes a month, the faculty member completes a survey instrument that assesses the entire process and its value to the individual faculty member.

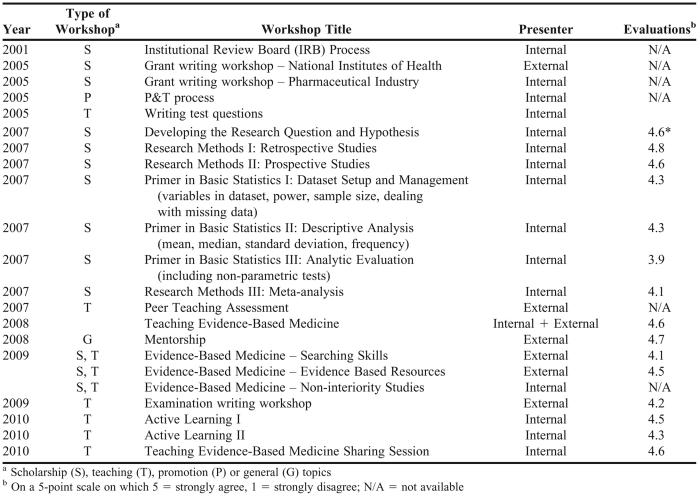

Faculty Development. Facilitating faculty development programs is a key component of the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee's activities. There are 4 main sources of input on faculty development needs: the needs assessment of faculty members conducted every 2 years by the Center for Academic Performance and Enhancement; input from college administrators; feedback from other college committees; and ideas gained through attendance at professional meetings, such as the AACP Institutes. Based on this input, the committee prioritizes areas for workshop development. To successfully execute these development programs, a small budget is allocated for management by the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee at the beginning of each academic year. Workshops have included diverse topics and featured internal speakers from the college as well as external presenters, including those from other universities and agencies such as the National Institutes of Health (Table 3). Because the vast majority of the faculty development workshops have been designed in response to needs expressed by faculty members, the programs have been well received and evaluations have been positive. However, faculty “buy-in” on some programs (eg, peer assessment of teaching) that were developed based on topics gleaned from attendance at AACP institutes and/or information from the literature have required considerable effort.

Longitudinal Faculty Development. Two longitudinal faculty development programs that were created in 2009 and have been in place for 3 years are undergoing CQI following assessment. One of the programs is the peer assessment of teaching process that was adapted from the University of Colorado.11 Since implementation, 14 faculty members have been formatively assessed. These faculty members have reported that the process has helped them reflect on and improve their teaching. The other longitudinal program is the mentorship program that was initiated in response to requests from new and/or junior faculty members. Committee development of the mentorship program involved conducting an extensive literature review, hosting a seminar by an invited expert, and creating forms for identifying protege needs, assessing the mentorship program, etc. Approximately 15 mentor-protégé pairs have participated in the mentorship program and have provided positive feedback and valuable insights for improvement.

Evaluation. The evaluation process was a Faculty Orientation and Development Committee function until the College of Pharmacy Assessment Committee was formed in 2006. The process designed by the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee was based on a comprehensive “360o” assessment and included student evaluations of the course, the course coordinator or facilitator, and participating instructors; faculty evaluation of administrators; and performance evaluation documents for faculty members by department chairs. Each of these components was developed using a combination of information from the literature, faculty input, and implementation followed by feedback and CQI.

Only the faculty member evaluation of administrators is under the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee's purview. Administrators are evaluated according to the following categories: leadership, management, and communication. Approximately 5 administrators (dean, associate deans, assistant deans, department chairs, and directors in direct contact with faculty members) have been evaluated each year using this process. Administrators who have been assessed find these annual evaluations helpful in understanding how they are perceived, planning for the short and long term, and in improving their communication and management styles.

Outcomes

Each Faculty Orientation and Development Committee program is evaluated at the end of the program using survey tools as well as annually by the committee to determine its value and whether it should continue to be offered.

Faculty Orientation. The average score given by the 19 faculty members who underwent the orientation process from 2001 to 2010 was 3.4 on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree). The faculty members’ responses indicated that the program helped them to ease into their work at the university, understand what was expected of a new faculty member, and feel welcomed by faculty and staff members. As part of the annual CQI process, feedback from new faculty members has led to changes that have improved the program such as: adding individuals in different roles who new hires need to meet, providing more time for the orientation process, regularly training support staff members in the orientation process, and placing key documents and workshop materials on a server for easy future access.

Faculty Development. From 2001 to 2010, 19 faculty development workshops were conducted, ranging from 1 in 2001 to 8 in 2007. Attendance at these workshops was about 20% in the early years but gradually increased and has remained at 66% to 75% for the past 3 years (Table 1). On a 5-point scale (5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree), the average assessment score was 4.4 (range 3.9 to 4.8), indicating high faculty satisfaction with the individual workshop sessions.

Table 1.

Faculty Development Workshops Sponsored by the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee From 2001-2010

The AACP Faculty Survey conducted in 2010 demonstrated that nearly 95% of faculty members at our college of pharmacy report that programs are available to help improve teaching skills, which was 10% higher than peer comparison schools. In addition, over 80% of faculty members at our college of pharmacy reported that programs were available to help develop research and scholarship, a rate 25% higher than peer comparison schools. The trend was similar based on results from earlier AACP surveys (2008).

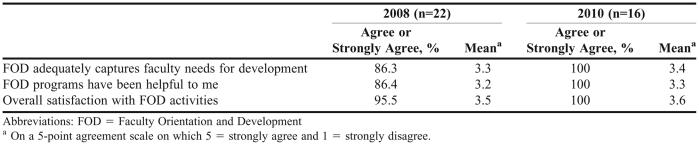

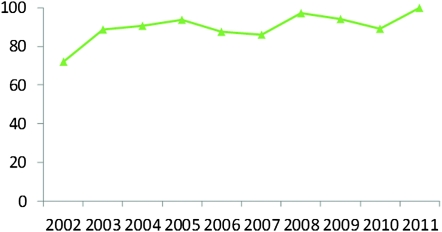

Satisfaction with FOD Activities. The overall satisfaction with committee activities has been consistently near 100% (Table 2). Over 85% of faculty members routinely report that the committee adequately addresses faculty development needs and is helpful. There has also been an upward trend in faculty retention data since the committee was established (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Faculty Satisfaction with Faculty Orientation and Development Committee Activities, N = 35

Figure 2.

Percentage faculty retention 2002 (n = 25) to 2011 (n = 40).

DISCUSSION

The Faculty Orientation and Development Committee was conceived based on the need and desire of the college to assist faculty members in achieving success with a broad perspective from orientation to faculty development. The committee has always attempted to tailor programs to meet faculty needs. Identifying and addressing these needs in a structured format is especially vital for new faculty members with no or limited academic experience. Evidence from our program evaluations indicate that programs are well-received by faculty members, as might be expected when the program development and testing process is responsive to faculty needs. The success of the committee in our college has resulted in it becoming the role model for other colleges at our university who wish to develop their own faculty development programs.

Of the many factors that have contributed to the success of the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee and its programs, the following are the most noteworthy:

Well-defined policies and procedures (eg, staggering faculty terms and maintaining ex officio membership), as well as objective criteria and tools (eg, needs assessment and Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle) have been essential in maintaining the committee's effectiveness while reducing a “reinventing the wheel” syndrome each time FOD Committee membership changes.

Continuous support, with above-the line budgetary assistance, from college administration has facilitated autonomy in committee activities and program implementation.

Oversight by and feedback from the College of Pharmacy Dean's Council and Assessment Committee have ensured that the committee has remained relevant and valued by the college. The contributions of a core group of faculty members who have sustained the committee's growth across a decade and been invaluable to its continued progress and success.

Development of a stimulating, supportive work environment that facilitated good relationships among faculty within departments as well as between faculty members and administrators may increase job satisfaction and facilitate faculty retention.12,13 The Faculty Orientation and Development Committee within our college has evolved over the last decade as a core faculty-led initiative that provides a foundational culture of support within the college. While it would be challenging to definitively prove that the contributions of the committee directly enhanced faculty recruitment or improved faculty retention, there has been a corresponding increase in attendance at workshops, higher evaluation scores at workshops, and continued high levels of satisfaction with the committee's activities. The culture of an institution often plays a large role in faculty retention, and a culture of faculty support and development may be the byproduct of the Faculty Orientation and Development Committee's activities in the long term. Our data and experience indicate that a strong, organized faculty orientation and development program focused on faculty needs may facilitate faculty recruitment and improve faculty satisfaction, which is a precedent to faculty retention.

Appendix 1. A bibliography is provided for further reading on faculty orientation and development.

Bibliography for Further Reading

Latif DA, Grillo JA. Satisfaction of junior faculty with academic role functions. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65:137–44.

MacKinnon GE. An investigation of pharmacy faculty attitudes toward faculty development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(1)Article 11.

The Report of the 1991-92 Council of Deans/Council of Faculties Joint Committee on Faculty Recruitment and Retention: Contemporary Issues Surrounding the Recruitment and Retention of Pharmacy Faculty Members. Am J Pharm Educ. 1993;57:43-50S.

Report of the Teachers of Pharmacy Practice Task Force on Faculty Resource Development and Renewal. Am J Pharm Educ. 1994;58:228-235.

Report of the Task Force on the Recruitment and Retention of Pharmacy Practice Faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 1995;59:28-33S.

AACP Leadership: The Nexus between Challenge and Opportunity: Reports of the 2002-03 Academic Affairs, Professional Affairs, and Research and Graduate Affairs Committees. July 2003. Available at: http://www.aacp.org/site/tertiary.asp?TRACKID=Y2YZ8FXTFE5LU6LZP8EYD9PECR52W3QP&VID=2&CID=842&DID=5639 Accessed January 2, 2007.

AACP COD-COF Faculty Recruitment and Retention Committee Final Report. June 14, 2004. Available at: http://www.aacp.org/ Docs/AACPFunctions/Governance/6177_AACPCommitteeonRetentionFinalReport.pdf Accessed January 2, 2007

Penna RP. Academic pharmacy's own workforce crisis. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65:26–31S.

Carter R. Planting faculty seed. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69((1))Article 94.

Leslie S. Pharmacy faculty workforce: increasing the numbers and holding to high standards of excellence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69((1))Article 93.

Patry RA, Eiland LS. Addressing the shortage of pharmacy faculty and clinicians: The impact of demographic changes. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2007;64:773–775.

American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. June 2007 Profile of Faculty. Available at: http://www.aacp.org/Docs/ MainNavigation/InstitutionalData/7813_SCANNER94_1015_000.pdf Accessed June 12, 2007.

American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Vacant Budgeted and Lost Faculty Positions. Available at: http://www.aacp.org/ Docs/MainNavigation/InstitutionalData/8087_IRBNo7-Facultyvacancies.pdf Accessed June 12, 2007.

American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy 2006 Profile of Students. Available at: http://www.aacp.org/site/page.asp? TRACKID=Y2YZ8FXTFE5LU6LZP8EYD9PECR52W3QP&VID=1&CID=1420&DID=8230 Accessed June 12, 2007.

American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Bethesda, MD, 2007.

American College of Clinical Pharmacy, Lenexa, KS, 2007.

Report of the 2006/2007 COF/COD Task Force on Faculty Workforce, June 15, 2007, pages 11-18. http://www.aacp.org/Docs/ AACPFunctions/Governance/8296_FinalFullFacultyWorkforceReport2007.pdf Accessed August 6, 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cline RR. Disequilibrium and human capital in pharmacy labor markets: evidence from four states. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(6):702–709. doi: 10.1331/154434503322642633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Vacant budgeted and lost faculty positions – academic year 2008-09. http://www.aacp.org/resources/research/institutionalresearch/Documents/IRB%20No%2010%20-%20Faculty%20vacancies.pdf Accessed December 14, 2011.

- 3.Sheaffer EA, Brown BK, Byrd DC, et al. Variables impacting an academic pharmacy career choice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(3):49. doi: 10.5688/aj720349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Academic Pharmacy's Vital Statistics. Institutions and programs. http://www.aacp.org/about/Pages/Vitalstats.aspx. Accessed December 14, 2011.

- 5.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Joint Commission on Community Pharmacy Practice (JCCP) Future Vision of Pharmacy Practice. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark CA, Mehta BH, Rodis JL, Pruchnicki MC, Pedersen CA. Assessment of factors influencing community pharmacy residents' pursuit of academic positions. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1):Article 3. doi: 10.5688/aj720103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raehl CL. Changes in pharmacy practice faculty 1995-2001: implication for junior faculty development. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(4):445–462. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.7.445.33678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deming WE. The New Economics. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 1993. Center for Advanced Engineering Study. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Draugalis JR, Slack MK. A continuous quality improvement model for developing innovative instructional strategies. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63(3):354–358. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boucher BA, Chyka PA, Fitzgerald WL, et al. A comprehensive approach to faculty development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;(2):70. Article 27. doi: 10.5688/aj700227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor CT, Berry TM. A pharmacy faculty academy to foster professional growth and long-term retention of junior faculty members. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):Article 32. doi: 10.5688/aj720232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kehrer JP, Kradjan W, Beardsley R, Zavod R. New pharmacy faculty enculturation to facilitate the integration of pharmacy disciplines and faculty retention. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1):Article 18. doi: 10.5688/aj720118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen LB, McCollum M, Paulsen SM, et al. Evaluation of an evidence-based peer teaching assessment program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(3):Article 45. doi: 10.5688/aj710345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beardsley R, Matzke GR, Rospond R, et al. Factors influencing the pharmacy faculty workforce. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;(2):70. Article 34. doi: 10.5688/aj720234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spivey CA, Chisholm-Burns MA, Murphy JE, Rice L, Morelli C. Assessment of and recommendations to improve pharmacy faculty satisfaction and retention. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2009;66(1):54–64. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]