There are three myths about the role that the public can play in determining their health, said Professor Marcus Longley, Director, Welsh Institute for Health and Social Care, and Professor of Applied Health Policy, University of Glamorgan: they cannot weigh risks and benefits; scientific uncertainty is dangerous for lay people; and most people would simply rather not know.

As with all myths there is an element of truth in these statements but modern thinking about public health is more nuanced. An independent report based on the latest evidence from behavioural economics and psychology concluded that ‘People do not smoke or drink too much because they are ignorant, stupid or perverse – rather, it is the combination of the enjoyment that they get from these things and wider social or other environmental factors that mean they find it hard to adopt healthier behaviours [1]’. People gain something from unhealthy behaviours and they make an implicit trade-off of risks and benefits in choosing to continue them. Government needs to take this into account when forming its public health messages, a second report found, and it should place greater weight on informed choice and individual capacity [2].

The goal of public health policy has long been to increase life expectancy but this has been pursued at the cost of quality of life in later years [3]. Recent years have shown that preaching to people does not persuade them to change their lifestyle, so why not take a medicine that achieves that end more easily? The combined oral contraceptive is a case in point. The counter argument, Professor Longley said, is that it is risky, usually does not work, it discourages people from trying to be healthy and it turns people into patients.

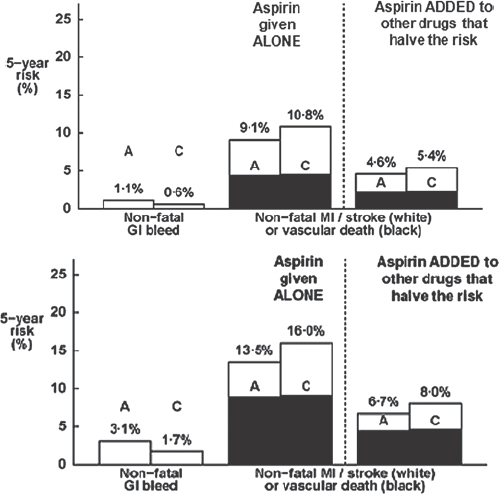

What do we understand by ‘risky’? The risk of fatality for a 50 year-old man taking aspirin to prevent a coronary event is 10 per 100,000 person-years of use. This is about the same risk as being a passenger in a car (11 per 100,000 person-yrs) and far lower than for a motor-cyclist (450 per 100,000 person-years [4]). The interpretation of risk varies between individuals and depends partly on what outcomes – death, disability, pain – are important to them.

Five years ago, before the association between aspirin and cancer risk reduction was publicised, Professor Longley and Professor Elwood convened a Citizens’ Jury to consider what information should be provided to the public and how it should be delivered [5]. Citizens’ Juries are not a new idea, he said, because they have been determining questions of guilt and innocence for over 800 years. In this case, they are based on the premise that ordinary people – if given the opportunity and enough time, support, resources – are capable of arriving at decisions about complex policy matters. Paid jurors consider, over 3–4 days, evidence from expert witnesses whom they cross-examine; after facilitated discussion, they jointly formulate policy recommendations.

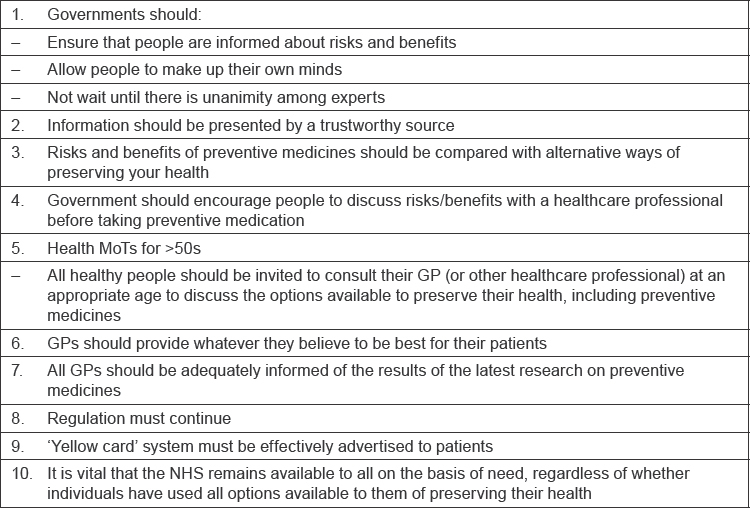

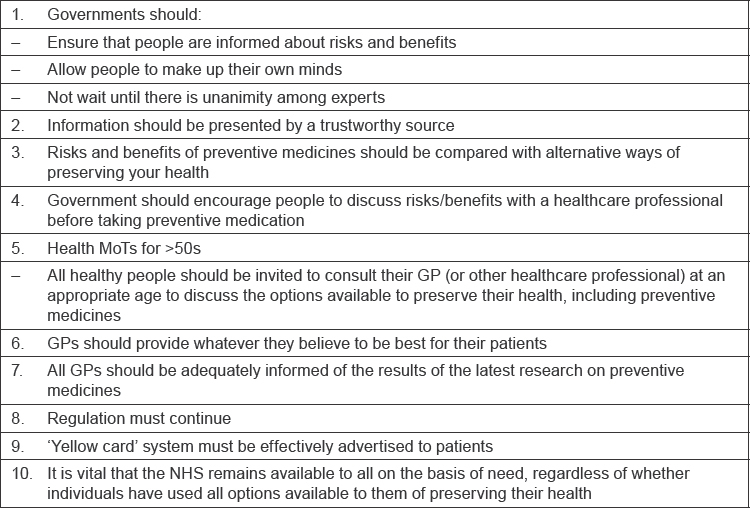

In this trial, the 16-member jury considered the case of cardioprevention with low dose aspirin. Jury members were a diverse group with contrasting views pre-trial views about aspirin but they collaborated effectively to develop 10 recommendations (Table 1). These show that jurors were less protective of themselves than is believed. It is possible to have an adult conversation about health with the general public, Professor Longley commented.

Table 1:

Citizen’s jury recommendations on the use of low-dose aspirin for cardioprevention [5].

Considering the three myths, Professor Longley said that the Citizen’s jury showed that the public can weigh scientific evidence, though they need a process and support to do so and this is resource-intensive. They can deal with uncertainty – jurors wanted to be informed even about issues that were controversial among scientists. It was less clear whether the jury refuted the assertion that people would rather not know.; Professor Longley suspected that health was not an important issue for some people.

Questions remain. How can the views of vulnerable people be represented? What are the resource implications for clinicians? Can this approach work for issues that are less clear than the aspirin debate? Do health professionals and the public share a common understanding about what constitutes ‘health’, and is it more important to some people than others?

![Figure 1[1]](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/669b/3298410/bf4d53613bc8/ecancer245fig5.jpg)

![Figure 2[1]](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/669b/3298410/ec5b6d152a09/ecancer245fig6.jpg)

![Figure 3[1]](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/669b/3298410/ddfad0e60473/ecancer245fig7.jpg)