Abstract

Introduction

In American Samoa, a US Territory in the South Pacific, over half of reported injuries are attributed to dog bites. Despite years of public outcry, little has been done to adequately address these preventable injuries that affect all age groups of both sexes.

Objective

To describe a serious public health hazard in American Samoa that may plague other jurisdictions that tolerate a significant free-roaming dog population.

Methods

A limited data set of outpatient records from 2004 through 2010 from the Territory's only emergency department listing an ICD-9-CM E-code of E906.0 (“dog bite”) in the primary E-code field provided a record of dog bite injuries. A survey of 437 adolescents documented their experiences regarding unprovoked dog attacks during the 2010/2011 school year.

Results

The sex/age group with the highest incidence for dog bite treatment was males 55 to 59 years of age (73.1 per 10,000 population per year) followed closely by males 10 to 14 years of age (71.8 per 10,000 population per year). Males aged 5 to 14 years accounted for 23% of all emergency department visits for dog bites. About one-third of adolescents reported having been bitten by a dog between September 2010 and May 2011. About 10% of males and 16% of females attributed the fear of being bitten as a factor preventing them from getting more physical activity.

Conclusions

Children, adolescents, and the elderly are the most vulnerable to dog bite injuries. Emergency room records may reflect only about a quarter of all such injuries.

Implications

Unprovoked attacks by aggressive, free-roaming dogs degrade quality of life by placing an untenable burden on the health care system and imposing physical and psychological barriers toward a more healthful lifestyle that includes walking, jogging, and bicycling.

Keywords: American Samoa, dog bite, obesity, physical activity

Introduction

American Samoa is a US-affiliated Territory in the South Pacific with a 2010 population estimated at 79,644.1 Each year since 1998 over half of reportable injuries were attributed to dog bites.1,2 This statistic most likely goes back much earlier. In a 1983 decision against the Government of American Samoa for failing to enforce its dog license law, the High Court Chief Justice described the Territory's dog population as “…scrawny, emaciated, mangy, in-bred, flea-bitten, diseased. Sophisticated world travelers usually refer to the dogs of Mexico and China as the worst looking dogs in the world. Compared to the dogs of American Samoa, the dogs of Mexico and China could qualify as best of their class at Madison Square Garden.”3 Furthermore, the number of reported dog bites may represent only a small proportion of all dog bites; published estimates of this proportion in the United States range from 10% to 50%.4

Although American Samoa is rabies-free, its free-roaming dogs impact human health in several ways. Their incessant barking and occasional fighting throughout the night interfere with restorative sleep. Infected dogs spread hookworm and roundworm in their feces and leptospirochetes in their urine. Worm larvae can penetrate the skin of barefooted children who may also inadvertently ingest worm eggs or larvae in dirt. Hungry dogs tip over garbage cans in their search for food, scattering trash which attracts rats—another vector of leptospirochetes—and littering the environment. In addition to inflicting pain, dog bites lead to a risk of infection and sometimes result in a permanently disfiguring wound. Perhaps most traumatizing of all is the risk of psychological scarring. The victim may develop a heightened fear while walking or may be deterred from walking at all. This is particularly disconcerting given the high prevalence of overweight and obesity and corresponding high incidences of obesity-related non-communicable diseases.5–9 Consequently, intervention strategies that call for increased outdoor physical activities such as walking, jogging, or bicycling may be challenging to implement.

Yet little official action against the large population of roaming dogs was taken until 2005 with the creation of a Task Force on Stray Animal Prevention and Remediation.10 Members of seven government departments, working with other departments and community organizations, were tasked with decreasing the stray dog population, dog-bite injuries, and spread of diseases—such as leptospirosis11 and intestinal worms—from dogs to humans. Moreover, they were to increase public awareness in regard to the responsible management and care of pets. But these objectives proved to be intractable. The Task Force leader responded to complaints of roaming stray and sick dogs, raised by businesses and organizers of a Pacific Arts Festival, in the 7 June 2008 issue of Samoa News, a local newspaper. He retorted that without the cooperation of village mayors to help identify strays from owned dogs, efforts to carry out the mandate were being met with resistance and even threats by residents. Although owners are required to provide their dog with a license—a $5 fee—few do. As a consequence, it is difficult to distinguish owned dogs from strays. An observational canine population study conducted at that time by the American Samoa Humane Society estimated the probable dog population on Tutuila Island at 2,025.12 Nearly nine of ten were freely roaming owned dogs and only about 9% strays.12 Of the owned dogs, only 3% were licensed.12

The local Department of Agriculture spays and neuters dogs each Wednesday for $25. On a typical day about eight to 10 females and four or five males are serviced and a half-dozen sick, aged dogs are euthanized at its veterinarian clinic (Leoleoga Leituala, telephone conversation with DV, 20 June 2011). Since 2005 clinic staff euthanized 1,925 dogs brought in by the owner, captured by the stray dog Task Force, brought in by the police because of their vicious behavior, or collected by staff (Leoleoga Leituala, telephone conversation with DV, 20 June 2011).

In February 2010, following a magnitude 8.1 earthquake and tsunami on 29 September 2009 that claimed 34 lives in American Samoa and another 149 in the independent nation of Samoa, a team of visiting veterinarians sterilized 432 cats and dogs on American Samoa and 584 on Samoa.13 They reported that stray dogs on both islands were generally not socialized to humans and had formed packs. Most were dehydrated and malnourished, many of them limping or with open wounds from fights. About 70% had severe sores caused by debilitating transmissible venereal tumors.13

A feature article in the 16 October 2010 Samoa News addressed the rising population of roaming canines. Residents in the port village of Fagatogo were especially concerned about the image the Territory was presenting to the thousands of cruise ship passengers who visit annually. Pedestrians had to step over or walk around sickly, mangy, disease-ridden dogs that sat in front of stores and along the road, most of which were actually “owned” dogs. The story was followed by a spate of articles attesting to people's fear of dogs and its deterrence to walking, jogging, and bicycling. One youngster mentioned his need to carry a stick in order to go to the bus stop. But perhaps the most aggrieved of all are meter readers for the local power and water utility. They often fall behind on their reading routes because they have to spend time combating dogs (Ryan Tuato'o, personal communication to DV, 20 November 2010).

Between January 2010 and February 2011, the American Samoa Community College conducted eight focus groups with Samoan adults in order to identify culturally acceptable supports for healthy living in the Territory.14 Among the many suggestions by the 74 participants was the need for local government to enforce a vicious dog law enacted in 1988.15 To that end, in May 2011 the first known case of a local resident to be prosecuted under the vicious animal law was sentenced to two years probation for an unprovoked attack on an 8-year-old boy in October 2007. At the time, the defendant owned 23 dogs.16

Methods

We obtained de-identified data from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Tropical Medical Center (LBJTMC) VistA Computerized Patient Record System of emergency room (ER) visits recorded between 7 January 2004 and 29 December 2010 having an International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) E-code of E906.0 (“dog bite”) in the primary E-code field. The limited data set comprised only the sex, age, village, and date of service of 1,873 patients, meeting specifications stipulated in Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Section 164.514(e).17 Coding was performed by uncertified Billing Department staff based on the diagnosis registered on an encounter form by the ER physician. We estimated incidences (that is, the number of ER visits per 10,000 population by sex and age group per year) using population projections for the year 2005.1

To understand what impact the fear of dogs may have on adolescents, we surveyed 220 males and 217 females aged 13 to 18 years between 23 May and 1 June 2011. This sample represented a population estimated at 6,000 adolescents in this age group,1 allowing for a 5% margin of error at the 95% confidence level. All were students from four widely dispersed public elementary schools and three public high schools on the Territory's main island of Tutuila. The survey was designed to measure knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding nutrition and exercise. It was conducted under the auspices of the American Samoa Department of Education for an Institutional Review Board-approved collaboration between the American Samoa Community College and Brown University, Providence, RI. Among 35 questions were four regarding dogs (Table 1). Space was allotted to allow students to explain their responses.

Table 1.

Dog bite-related questions on survey of American Samoan adolescents

| 1. Do any of the following keep you from exercising more than you currently do? |

| The cost of the activity Lack of time Lack of energy Lack of Transportation Fear of being bitten by a dog Fear of being teased or bullied Other: __________________________________________________________ |

| 2. Since school began last September, have you been bitten by a dog? |

| No Yes-by my family's dog Yes-by a dog whose owner I know Yes-by a dog whose owner I do not know or that may be a stray dog. |

| 3. If you answered YES to the above question… |

| I did not seek medical attention I or a family member treated the wound A traditional healer treated the wound A doctor treated the wound |

| If you answered YES to [Question 2], what happened to the dog(s)? |

| Nothing The owner confined the dog The owner destroyed the dog The police took the dog away Not sure/don't know |

Data from LBJTMC and the public schools were entered into and queried using Microsoft Access 97 database software. Chi-square tests were performed using SigmaStat 3.1. The curve smoothing algorithm, lowess, was from SigmaPlot 9.0. Both SigmaStat and SigmaPlot are from Systat Software, Inc.

Results

Emergency Room Visits

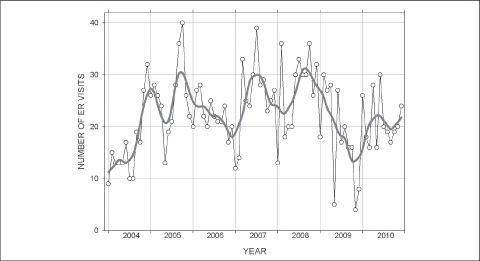

From 2004 through 2010, 1,873 visits to the ER were directly attributable to dog bites. Males accounted for 1,106, or 59%, of those visits. The number of visits varied significantly from month-to-month and year-to-year with no clear season when dog bite-related ER visits either peaked or plunged (Figure 1). But significantly less visits occurred on Sundays (138 visits) and significantly more on Mondays (310 visits) than during the rest of the week, which ranged from 224 to 248 visits (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Distribution of 1,873 ER visits to the LBJ Tropical Medical Center for dog bite injuries from 2004 through 2010 by year and month. The continuous curve is the result of smoothing the data using the lowess algorithm.

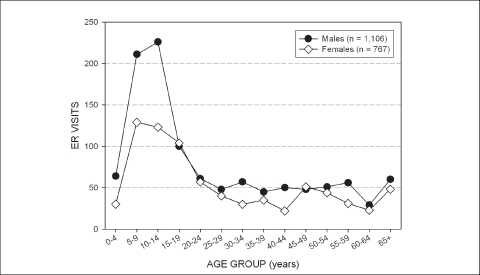

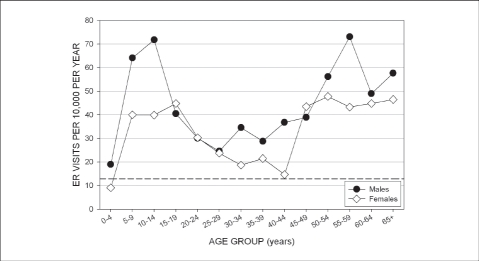

Males 5 to 14 years of age were most likely to be bitten, accounting for 23% of all visits for both sexes (Figure 2). Girls between the ages of 5 and 19 accounted for 46% of dog bite-related visits for females. But the highest incidence rate, 73.1 per 10,000 persons per year, was for males aged 55 to 59 followed closely at 71.8 per 10,000 males aged 10 to 14 (Figure 3). Average incidence rates per 10,000 were 44.7 for males, 33.5 for females, and 40.1 overall. Except for females below 5 years of age, incidence rates for all age groups of both genders exceeded the average incidence rate of 12.9 reported in the United States.18

Figure 2.

Distribution of 1,873 ER visits to the LBJ Tropical Medical Center for dog bite injuries from 2004 through 2010 by sex and age group.

Figure 3.

Incidences of dog bite-related injuries treated at the LBJ Tropical Medical Center ER based on 1,873 visits from 2004 through 2010, by sex and age group. Incidence is the average yearly number of ER visits per 10,000 individuals in each age group for each sex based on population estimates for 2005. The dashed line at 12.9 ER visits per 10,000 is the average incidence of annual dog bite-related injury visits to emergency departments in the United States from 1992 to 1994.18

Adolescent Survey

Of the 220 males who were asked what prevented them from getting more exercise, 23 (10.4%) responded that it was their fear of being bitten by a dog. For females, 36 (16.6%) selected this response. Only “lack of time” (195 responses) and “lack of energy” (109 responses) elicited a greater number of responses than did the fear of being bitten (Table 1). During the eight-month period on which the students were asked to report, 75 (34.1%) males and 68 (31.3%) females reported being bitten by a dog. One male reported being bitten three times. Family-owned dogs accounted for 40% of all bites while other-owned dogs and strays accounted for 34% and 26%, respectively. Several students wrote that the family dog belonged to a relative who lived in a different village, and that they were bitten while visiting. In most instances, nothing was done about the dog. But 11 students (8%) reported that the family-owned dog was either destroyed by the owner or taken away by the police. This same pattern was reported for dogs owned by others in the village and for strays, that is, generally nothing was done about the dog. Survey responses did not differ significantly by sex.

Only 25% of the students reported being treated by a doctor. This is in accord with an estimated 20% of dog bite victims in the United States that sought medical attention.19 Fully 30% of the bites were not treated at all, while 37% were treated by a family member (usually the mother) and 8% by a traditional herbal healer.

The 37 students who commented on their experiences generally related the circumstances surrounding the bites or they expressed their outrage toward the dog or its owner. Typical comments were:

“I was walking on the road and the dog bit me.” (Male, age 15)

“I was just walking and suddenly the dog bit me.” (Female, age 14)

“I stoned the stupid dog.” (Male, age 15)

“I want to kill that dog.” (Female, age 18)

“They never did anything about their dog and it is not right.” (Female, age 14)

“The owner of the dog just sat there doing nothing.” (Female, age 17)

“The cop said they were going to put it down, but I still see it around.” (Male, age 14)

Discussion

The disparity in the number of dog-bite-related visits to the ER between Sundays and Mondays, compared with the rest of the week, may be owing to the absence of public transportation on Sundays rather than to the actual number of injuries occurring on either day. Alternatively, in the Samoan culture, Sundays are devoted to church followed by a large family meal, or toanai'i, with sports and other noisy activity frowned upon. Therefore, the decreased number of ER visits on Sundays might also be owing to decreased contact with dogs. But this would not explain the increased number of ER visits on Mondays. Because the increased number of ER visits on Mondays is about equal to the decreased number of ER visits on Sundays, a significant proportion of dog bite victims bitten on Sunday appear to delay visiting the ER until Monday. Most residents cannot afford to own cars. Although taxi service is available at all times, it is much more expensive than privately owned buses that operate Monday through Saturday and serve as the chief means of public transportation.

The number of actual dog bite injuries may be four or five times greater, or more, than the number recorded by the hospital ER, since not all victims seek medical attention. Furthermore, patients who visit the ER for a dog-bite-related infection rather than for the dog bite per se may have the visit listed under a different ICD-9-CM E-code. In any case, the incidence of dog-bite injuries for nearly all age groups of both sexes far exceed the average annual incidence of 12.9 visits per 10,000 reported in the United States.18

Although dog bite injuries are the most frequent of reportable injuries in American Samoa and are largely preventable, efforts to address this perennial problem have had little impact. Unlike in the United States, where dog owners are usually covered by homeowners or renters insurance policies, most dog owners in American Samoa have no coverage for dog bite claims. Consequently, victims are rarely compensated for their injuries because dog owners are rarely held accountable for their pets. Besides pain and suffering directly attributable to the bite, victims may suffer life-altering emotional trauma that goes undiagnosed and untreated.

Medical attention is provided “free of cost” by the American Samoa Government to all citizens,20 with only a $10 user fee for each visit and each prescription filled. Funds for medical care are primarily from the US Medicaid program together with one-to-one matching funds from the American Samoa Government. For fiscal year 2011, federal Medicaid spending was capped at $11.5 million (Michael Gerstenberger, e-mail to DV, 22 July 2011). Yet the current economic recession makes it difficult for the American Samoa Government to meet its mandated contribution.21 Like other US-affiliated insular areas, the Territory has no individual eligibility process for Medicaid, so these funds are used to supplement the costs of services for all users, not just the genuinely poor or low income.22 Furthermore, the State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) allows children who have medical diagnoses to be treated as individuals regardless of parental income. American Samoa received only 1.2%, or $630,000, of available CHIP allotments to US insular areas in 2008.22 Consequently, U.S. and local taxpayers absorb the costs for treating dog-bite victims. American Samoa reports only aggregate spending for health care because its program is not designed to track spending by service.22 Therefore, the cost for treating victims of dog bite cannot be accurately determined. The public, uninformed of the financial impact of dog bite injuries, are thereby unaware of the extent this highly preventable injury diminishes the limited pool of health care resources for all.

Free medical service might, ostensibly, account for a proportionately greater number of people visiting the ER for dog bite treatment compared with the United States. But user fees and long waiting times to see a physician deter visits to the ER for trivial ailments, especially for over 61% of the population who live below the Federal Poverty Level 23 and rely upon dawn-to-dusk only public transportation.

But the negative impact of dog bites goes beyond physical injury and psychological distress. A 2007 report of non-communicable disease risk factors found that 93.5% of the American Samoan adult population aged 25 to 64 was overweight or obese, and 74.6% were obese.5 Moreover, 47.3% were diabetic—one of the highest rates in the world. Childhood obesity rates are equally alarming. In the early 1980s, 4% of boys and 8% of girls were obese.6 By 2005, the obesity rate for both sexes was about 33% with an additional 29% overweight.6 Because obesity is the driving force behind several non-communicable diseases that require extremely expensive long-term treatment, the health and financial wellbeing of individuals, families, and government will require that the obesity epidemic be brought under control.

Making communities safer for pedestrians, joggers, and bicyclists will not, of itself, reduce obesity. Opportunities for increased physical activity must coincide with prudent dietary habits by individuals who choose to follow a healthful lifestyle. Given that most students in our survey listed ‘lack of time’ and ‘lack of energy’ as the overriding reasons for not engaging in more physical activity, intervention must also focus on motivational strategies. Yet physical activity is an indispensible part of the solution. The current recommended minimum level of physical activity for adults 18 to 64 years old is 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity.24 Children and adolescents six to 17 years old should do 60 minutes or more of moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity daily.24 The simplest, quickest, and least expensive way to meet these guidelines is through brisk walking. Proven intervention strategies such as Safe Routes to School and Walkable Communities stand little chance of succeeding while aggressive dogs—owned or otherwise—are free to prowl. In an environment where aggressive dogs are the norm, residents may have become inured to the situation. In contrast, visitors to the Territory become acutely aware of the problem within a day or two. The problem might be summarized in the words of Thomas Paine who, in referring to another objectionable situation, stated: “A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong gives it a superficial appearance of being right.” We believe that dog-owners who are indifferent to the harm their animals inflict on people using the public right-of-way must be made to feel the full brunt of the law.15 Likewise, well-meaning individuals who feed and shelter abandoned dogs must also accept responsibility for neutering males that display dominance aggression, spaying females, and confining or euthanizing any dog involved in an unprovoked attack.

In his 1983 decision against the American Samoa Government cited at the beginning of this paper, the Chief Justice referred to the dog situation as a “disgrace” that was not always so. He noted that “During the Naval Administration [before July 1951] a dog license law was strictly enforced and any dog without a collar was quickly disposed of by the Fita Fita guard.”3 Dog bite prevention is an intangible quality of life issue that ultimately must be confronted by the community at large. An existing guide25 for achieving this goal might be modified to accommodate cultural sensitivities and economic constraints. Unless and until society is made fully aware of the costs associated with the problem—in terms of physical and mental health as well as in dollars—there will be little incentive for action.

Conclusions

The United States considers an annual incidence of 12.9 dog bite treatments per 10,000 individuals to be a major public health problem. During the seven year period from 2004 through 2010 the average annual incidence in American Samoa, 40.1 per 10,000 individuals, was over three times the US incidence, which underscores the necessity to address this issue. One-third of adolescents reported being bitten by a dog during the eightmonth period of the last school year. Of these, 10.4% of males and 16.6% of females cite a fear of dogs as the reason for not getting more physical activity. Unprovoked dog attacks can cause physical and emotional injury and may deter residents from engaging in outdoor exercise. Changing the social norm will require a broad based approach involving communities and government working together.

Acknowledgements

We thank staff of the LBJTMC MIS office for providing outpatient records of dog bite-treated injuries; American Samoa Department of Education for allowing us into their classrooms, and especially students who shared their experiences and opinions with us; Sharon Fanolua and Marie Chan Kau for their excellent technical assistance; Cheryl Morales Polataivao, Ashley M. Stokes, and two anonymous reviewers for critiquing the manuscript; and Eileen Herring for locating references unavailable to us. Financial support was provided by a US Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative grant, CRIS Accession No. 216929, administered by the American Samoa Community College.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.American Samoa Statistical Yearbook 2006. [December 6, 2011]. Department of Commerce, Statistical Division. Available at: http://www.spc.int/prism/country/as/stats/fnl06yrbkhome.pdf.

- 2.World Health Organization, author. Country Health Information Profiles, American Samoa. 2009. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/86F483F0-9367-416C-8237-C3F0BD117240/0/5finalAMSpro2010.pdf.

- 3.Savage Jason, et al., editors. Plaintiff, v. Government of American Samoa, et al., Defendants. CA No. 83-32. 7 June 1983. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.asbar.org/Cases/Second-Series/1ASR2d/1ASR2d102.htm.

- 4.Overall KL, Love M. Dog bites to humans—demography, epidemiology, injury, and risk. JAVMA. 2001;218:1923–1934. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.218.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization, author. American Samoa NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report, March 2007. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/Printed_STEPS_Report_American_Samoa.pdf.

- 6.Davison N, Fanolua S, Rosaine M, Vargo DL. Assessing overweight and obesity in American Samoan adolescents. Health Promot Pract. 2007;14(2):55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obesity Study Committee, author. Prevalence of overweight in American Samoan schoolchildren: Report to the Directors: Department of Health, Department of Education, August 2007. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/adap/ASCC_LandGrant/Dr_Brooks/TechRepNo47.pdf.

- 8.Obesity Study Committee, author. Prevalence of overweight in American Samoan schoolchildren: Report to the Directors: Department of Health, Department of Education, June 2008. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/adap/ASCC_LandGrant/Dr_Brooks/TechRepNo48.pdf.

- 9.Obesity Study Committee, author. Prevalence of overweight in American Samoan schoolchildren: Report to the Directors: Department of Health, Department of Education, May 2009. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/adap/ASCC_LandGrant/Dr_Brooks/TechRepNo56.pdf.

- 10.Governor's Stray Dog Control Task Force, author. General Memorandum No. 148-2005. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.ashumanesociety.org/straygov.pdf.

- 11.Simms JR. Animal leptospirosis in the Federated States of Micronesia. Pac Hlth Dialog. 1998;5(1):30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krosch S. Canine population study for Tutuila Island, American Samoa. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.ashumanesociety.org/popstudy.pdf.

- 13.Clifford E. American and Independent Samoa Island Campaign Report, April 2010. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.animalbalance.net/files/Samoa_Report_April_2010.pdf.

- 14.Identifying supports for and barriers to healthy living in American Samoa. USDA CSREES Award No. 2009-55215-05188, CRIS Accession No. 216929. Manuscript in preparation.

- 15.American Samoa Code Annotated 25.1610. Vicious animals prohibited - Penalty - Enforcement. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://asepa.gov/_library/documents/legal/ascatitle25ch16domesticanimalspiggeries.pdf.

- 16.Samoa News. Court News, Samoa News, 18 May 2011. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.samoanews.com/storyid=26562&edition=1305709200.

- 17.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, author. Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule, Health Information Privacy. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/summary/index.html.

- 18.Weiss HB, Friedman DI, Coben JH. Incidence of dog bite injuries treated in emergency departments. JAMA. 1998;279(1):51–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. Dog Bite Prevention. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/dog-bites/biteprevention.html.

- 20.American Samoa Code Annotated 13.0602. Persons entitled to free medical attention - Limitation - Extent. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.asbar.org/Newcode/Title%2013.htm#chapter6.

- 21.Radio New Zealand International, author. American Samoa government constraints mean no money for LBJ hospital, posted 21 July 2011. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.rnzi.com/pages/news.php?op=read&id=61950.

- 22.GAO-09-558R Federal Medicaid and CHIP Funding in the U.S. Insular Areas. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d09558r.pdf.

- 23.Bureau of the Census, author. Population and Housing Profile: 2000: American Samoa. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2000/island/ASprofile.pdf.

- 24.U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, author. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010. [December 6, 2011]. Available at: www.dietaryguidelines.gov.

- 25.Beaver BV, Baker MD, Gloster RC, et al. A community approach to dog bite prevention. JAVMA. 2001;218(11):1732–1749. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.218.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]