Abstract

Pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (PCASL) MRI is a relatively new ASL technique and has the potential to extend the CBF measurement to all tissue types, including the white matter. However, arterial transit time (δa) for the white matter is not well established and a limited number of reports using multi-delay methods have yielded inconsistent findings. In the present study, we took a different approach and measured white matter δa, 1541±173 ms (mean±SD), by determining arrival times of exogenous contrast agent in a bolus tracking experiment. The data also confirmed δa of the gray matter as 912±209 ms. In the second part of this study, we used these parameters in PCASL kinetic models and compared relative CBF (rCBF, with respect to the whole brain) maps to those measured using a SPECT technique. It was found that the use of tissue-specific δa in the PCASL model was helpful in improving the correspondence between the two modalities. On a regional level, the gray/white matter CBF ratios were 2.47±0.39 and 2.44±0.18 for PCASL and SPECT, respectively. On a single voxel level, the variance between the modalities was still considerable, with an average rCBF difference of 0.27.

Keywords: arterial spin labeling, cerebral blood flow, contrast agent, PCASL, perfusion, SPECT

Introduction

Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) MRI provides a non-invasive technique to assess cerebral blood flow (CBF) (1–10). In particular, recent advances in ASL technologies, including the pseudo-continuous ASL (PCASL) method, 3D acquisition, and background suppression, have facilitated a broader application of this technique in neurological and psychiatric disorders (11–16). It has also been shown that, once a relative CBF (rCBF) map is obtained, the calculation of absolute CBF value can be feasibly achieved by using phase-contrast velocity map as a whole-brain calibration factor (17,18). A remaining challenge in ASL methodology is then how to obtain accurate rCBF maps. The present study will focus on the measurement of rCBF with PCASL and compare the results to those of a radiotracer-based Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) method.

An important feature of the present study is that we pay special attention to the ability of PCASL in measuring white matter rCBF. Recent evidence suggested that PCASL may have sufficient sensitivity to reliably detect signal in the white matter, which would provide a new means to assess white matter physiology (19). However, proper quantification of ASL signal requires the knowledge of a number of parameters (e.g. T1, T2*, blood-brain partition coefficient), in particular arterial transit time (δa), which is the time it takes for the blood to travel from the labeling site to the imaging slice. δa in the gray matter has been studied extensively by fitting multi-delay ASL data to kinetic models (20–25). Such studies in the white matter, however, yielded less consistent results, presumably due to lower signal amplitude (25–28). The present study takes a different approach by using exogenous contrast agent to estimate δa in both gray and white matters.

This study contains two components. First, we used the time difference of Gd-DTPA bolus arrival in the labeling and imaging slices to calculate δa. Next, using the δa values obtained above, we compared the rCBF maps using a PCASL technique (3,4,29,30) to those obtained from a SPECT method. The SPECT method is insensitive to the time it takes for the tracer to reach the parenchyma, therefore can serve as a reference technique to study the transit time effect in PCASL. Spatial correspondence was assessed between the SPECT and PCASL CBF maps. The PCASL data were analyzed with two kinetic models, including a simplified model (31) and a one-compartment kinetic model (20).

Materials and Methods

General

All MRI scans were performed on a 3T MRI system (Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) using a body coil for transmission and an eight-channel array coil for reception. The two components of the study, which were the transit time study and the SPECT comparison study, were performed on separate cohorts. All subjects gave informed written consent before participating in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Transit time study

Five subjects (4 females, 1 male, 34.4±6.1 years old) without history of neurological disorders participated in a bolus tracking MRI experiment. The protocol was similar to a dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) scan, in which a sharp bolus (5 ml/s) of Gd-DTPA (0.1 mmol/kg Magnevist®, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany) was injected intravenously while T2*-weighted MR images were acquired rapidly in the brain. A special consideration for accurate determination of δa was that a higher temporal sampling rate was used. Typical DSC scan uses a TR on the order of 1 second, which is too coarse for arterial transit time of 1–2 seconds. We therefore used a TR of 100 ms which allowed the simultaneous acquisition of two slices. The lower slice was at 84 mm below the anterior-commissure (AC) posterior-commissure (PC) line which was the location of the labeling plane in PCASL and provided the optimal labeling efficiency (17). The upper slice was at 10 mm above AC-PC line corresponding to typical imaging slice (see Fig 1a). The scan duration was 200 s (yielding 2000 measurements) and Gd-DTPA injection took place at 1 min after the start of scan. Other imaging parameters were: Field-of-view (FOV) 205×205 mm2, matrix 64×64, voxel size 3.2×3.2×5 mm3, TE 25 ms, SENSE factor 2, and flip angle 40°.

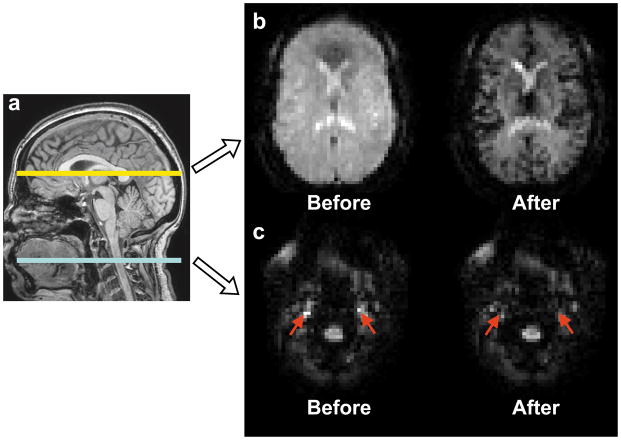

Figure 1.

Representative images from the transit time study. (a) An illustration of slice locations. Two slices were acquired during each measurement of 100 ms. The lower slice was located 84 mm below the AC-PC line, corresponding to the labeling plane in PCASL. The upper slice was located 10 mm above AC-PC line corresponding to a typical imaging slice in PCASL. (b) An example of images of the upper slice before and after the arrival of contrast agent bolus. (c) An example of images of the lower slice before and after the arrival of contrast agent bolus. Red arrows indicate the internal carotid arteries.

A high resolution T1 weighted image was acquired with the following parameters: Magnetization Prepared Rapid Acquisition of Gradient Echo (MPRAGE) sequence, TR/TE/TI=2100/3.8/1100 ms, flip angle=12°, 160 sagittal slices, voxel size=1×1×1 mm3, FOV=256×256×160 mm3, and duration 4 min. In addition, a PCASL scan with a short delay (w=200 ms) was acquired to delineate large vessels (24,32). Other PCASL parameters were identical to the ones used in the SPECT comparison study described below.

The raw signal time course of the bolus-tracking data is characterized by a signal drop from the baseline level upon the arrival of the Gd-DTPA bolus, followed by a gradual signal return (Fig. 2a). To estimate the bolus-arrival time, a second time course was calculated, in which the current time point together with seven points before and seven points after were used to calculate the slope of the signal change. Next, an automated algorithm was used to search for the time point at which the slope reaches 15% of the maximum slope (in this voxel) and this time point is expected to indicate the arrival of front edge of the bolus. The threshold value 15% was chosen to allow the bolus-related signal drop to be clearly distinguished from signal fluctuations associated with random noise. The algorithm was applied to each voxel in the image and a map of bolus arrival time (interpolated to 1ms temporal resolution) was obtained.

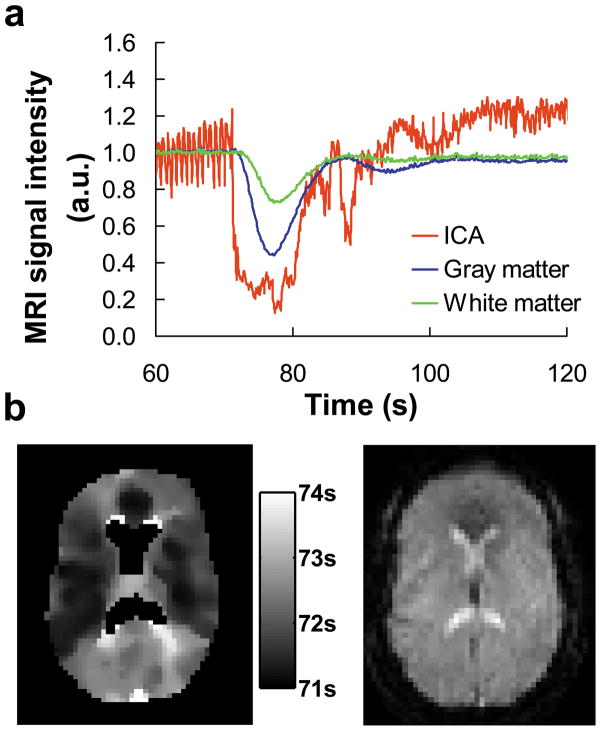

Figure 2.

Bolus arrival times obtained from the transit time study. (a) Signal time courses in the internal carotid arteries (ICA), gray and white matter in a representative subject. The injection of the contrast agent took place at time 60 s. The signals have been normalized to the pre-contrast levels for each ROI. Large fluctuations in the ICA are associated with cardiac pulsation effects. (b) Map of bolus arrival time. The arrival time was shown in reference to the start of the scan. The ventricle regions did not yield reliable fitting. Thus, the values in ventricles were excluded from the display. A pre-contrast image is shown on the right panel for anatomical reference.

ROI-based analysis was also conducted. For the lower slice, four ROIs corresponding to left/right internal carotid and vertebral arteries were manually delineated. For the upper slice, eighteen ROIs were delineated on each dataset, which included three major categories: large blood vessel, white and gray matter. The white and gray matter was each further divided into three sections corresponding to flow territories of anterior (ACA), middle (MCA) and posterior cerebral arteries (PCA) (33–35). Two deep gray matter ROIs corresponding to basal ganglia and thalamus were also included. The white and gray matter voxels were distinguished by tissue segmentation using a T1-weighted image resliced from the 3D MPRAGE based on angulation and translation parameters (SPM2, University College London, UK). The separation of anterior, middle and posterior sections was conducted manually based on a flow territory atlas (33). The ROIs for deep gray matter were manually delineated. The vessel ROIs in the upper slice were defined as voxels in which relative signal in the short-delay PCASL scan was greater than 7% of equilibrium magnetization, based on a previous study (24). As an exploratory analysis, ROIs were also manually placed in the sagittal sinus to assess how long it took for the blood to travel from major arteries to major vein, although these results had no utility in PCASL quantification.

For each ROI, an averaged time course was obtained and the bolus arrival time was determined as described above. δa was then calculated as the difference in bolus arrival times between the ROI in the upper slice and the feeding artery in the lower slice. Considering the flow territory of individual feeding artery, the posterior gray and white matter used the subtraction of bolus arrival time in the vertebral artery whereas all other ROIs used the internal carotid’s arrival time. δa values were compared across ROIs with Analysis-of-variance (ANOVA), followed by post-hoc pair-wise comparisons. A corrected P value of 0.05 or less is considered significant.

PCASL and SPECT comparison study

Ten subjects (7 females, 3 males, 39.3 ± 9.4 years old) without history of neurological disorders underwent both a PCASL MRI scan and a SPECT scan. The gap between the two sessions was 0–10 days with a mean value 3.2±3.4 days. Both PCASL and SPECT images covered the whole brain. The PCASL MRI scans used the following parameters: labeling duration 1650 ms, labeling RF flip angle 18°, RF interval 1ms, the labeling plane was located 84 mm below the AC-PC line as optimized previously (17), TR/TE=4151/14 ms, post-labeling delay time (w) = 1525 ms for the bottom slice with an increase of 35 ms for each additional slice, matrix size 80×80, in-plane resolution 3×3 mm2, 27 slices with the bottom slice at 55 mm below the AC-PC line, slice thickness 5 mm, no gap, 30 pairs of labeled and control images, duration 4.1 minutes. In addition, a T1-weighted MRPAGE scan was performed during the MRI session using sequence parameters identical to those described in the “Transit time study”.

For the SPECT study, a total of 20 mCi of CBF tracer Technetium-99m hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime (99mTc-HMPAO) (GE Healthcare, Princeton, New Jersey, USA) was administered over 30 s and followed by a 10 ml saline flush over 30 s. SPECT scans were obtained 90 min after 99mTc HMPAO administration to allow time for tracer activity to clear from blood and non-brain tissues. The SPECT image was acquired with a PRISM 3000S three-headed SPECT camera (Picker International, Cleveland) with ultra-high-resolution fanbeam collimators, positioned 13–13.5 cm from the axis of rotation (36). Projection data were acquired in a 128×128 matrix in 3° increments using a 20% wide centered energy window. The SPECT scan duration was 20 min. Image reconstruction were performed in the transverse domain by using filtered back-projection. The CBF-weighted images were filtered to a spatial resolution of 10×10×10 mm3. The images were corrected for incomplete extraction of the radio-tracer by using a permeability-surface-area (PS) model (37–39), in which CBFcorrected=CBFuncorrected/(1-exp(-PS/CBFcorrected)). PS for the 99mTc-HMPAO tracer was assumed to be 91 ml/100g/min according to the literature (37,39,40).

For data processing, PCASL image series were realigned to the first volume using SPM2. Pair-wise subtraction was conducted for the label and control images, and the difference images were averaged over multiple measurements. The PCASL and SPECT data of each subject were spatially transformed to a template CBF map available in SPM2, which is in the standard space established by Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI). To match the spatial resolution between the two modalities, the PCASL data were smoothed using a Gaussian kernel with full-width-half-maximum (FWHM) of 10 mm.

Two relative CBF maps were generated from the PCASL data for comparisons with the SPECT map: a simplified kinetic model of Chalela et al. assuming that the labeled spins stay inside blood compartment and do not enter tissue (31); and a one-compartment model of Alsop et al. (20). The calculation of CBF weighted signal in the simplified model used only one assumption that arterial blood T1a=1664 ms (41). The CBF signal was calculated as:

| [1] |

where w is the post-labeling delay time. The SPCASL of each voxel was then divided by the whole-brain-averaged SPCASL to obtain the rCBF map. In the one-compartment model, the CBF weighted signal was calculated as (20):

| [2] |

where τ is the labeling duration, λ is the blood-brain partition coefficient, T1 and T2* are the brain tissue relaxation times, and T1a is the T1 of arterial blood. Table 1 shows assumptions on gray and white matter model parameters. Note that the white matter δa value was previously not well established, and was one of the contributions of the present study. For each voxel, the actual model parameters were estimated based on its gray/white matter probability as:

| [3] |

where C is either T1, T2*, λ, or δa in Eq. [2] and P is the tissue probability. The tissue probability was obtained by performing tissue segmentation on the T1-weighted anatomic image using SPM2.

Table 1.

Parameter assumptions used in the one-compartment ASL model

Gray and white matter ROIs were manually placed on five representative axial slices, from which rCBF values were obtained. Caution was used in the ROI drawing to avoid voxels near gray/white boundary, so that partial volume effect could be minimized. The gray/white matter rCBF ratio was compared across modalities using a paired Student t test. Voxel-by-voxel comparison between PCASL and SPECT relative maps was conducted by assessing scatter plot between the two modalities. The scatter plot used a 10×10×10 mm3 voxel volume consistent with the image spatial resolution. To quantify the discrepancy between the two rCBF maps, a mean difference index, D, was calculated as (42):

| [4] |

where rCBFPCASL,i and rCBFSPECT,i are PCASL rCBF and SPECT rCBF values, respectively, for a voxel i, and N is the total number of voxels in the brain.

We further identified brain regions that showed significant differences between the two modalities by conducting a voxel-wise Student t test (SPM2) for the PCASL and SPECT rCBF maps. A threshold of P<0.001 and cluster size of >1.6 cm3 (200 voxels) was used to identify significant clusters.

Results

Figure 1 shows representative bolus-tracking images before and after the contrast agent injection, demonstrating sufficient signal and contrast even using a relatively short TR of 100 ms. Figure 2a shows time courses of MR signals in different ROIs. Voxels corresponding to large arteries showed an early and large bolus-associated signal drop due to high blood content, and they also manifested greater signal fluctuation due to cardiac pulsation. The signal decrease in the gray and white matter occurred at a later time with a smaller amplitude (Figure 2a). Figure 2b shows a representative map of bolus arrival time. No laterality in arrival times was observed. Thus, the left and right ROIs were combined. The Gd-DTPA bolus arrived at the internal carotid arteries slightly before vertebral arteries (by 297±233 ms, P=0.047). δa was then calculated from the arrival time differences. Table 2 listed the δa values by tissue types and ROIs. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in δa across vessel, gray and white matter. Post-hoc pair-wise comparisons also showed a pattern of increasing δa across these tissue types (corrected P<0.05). Within the gray matter, a significant difference was observed across sub-regions (P<0.001) with MCA territory having the shortest δa and thalamus having the longest δa. No differences in δa were observed across white matter sub-regions. The transit time from internal carotid artery to sagittal sinus was considerably longer, as expected (Table 2).

Table 2.

Arterial transit times (in ms) of different brain regions (mean ± standard deviation).

| Gray Matter | White Matter | Arterial Vessels | Venous Vessels | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 912±209 | 1541±173 | 425±119 | 4882±503 | ||||||

| ACA | MCA | PCA | Thalamus | Basal Ganglia | ACA | MCA | PCA | ||

| 959±206 | 805±190 | 1196±149 | 1685±277 | 953±295 | 1677±1022 | 1430±472 | 1634±347 | ||

ACA – anterior cerebral artery

MCA – middle cerebral artery

PCA – posterior cerebral artery

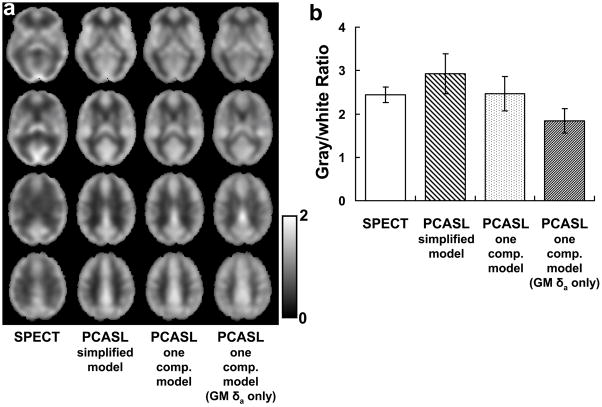

Figure 3a shows rCBF maps from SPECT and from PCASL using various models. Gray and white matter rCBF ratio from the ROIs is plotted in Figure 3b. The ratio using the simplified model was found to be significantly higher than that of SPECT (multiple-comparison-corrected P<0.005), suggesting a potential estimation bias using this model. The one-compartment model, on the other hand, yielded results relatively consistent with the SPECT (paired t test, P=0.7). Thus it seems that the use of the more comprehensive model is necessary for proper calculation of rCBF map. In addition, it was found that knowledge of δa in both gray and white matter is needed in order to avoid tissue-specific bias in the rCBF map. When identical δa was used for gray and white matter (assuming 912 ms for both tissue types), the gray/white CBF ratio was considerably under-estimated (P<0.001) (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Comparison between SPECT and PCASL results. (a) Relative CBF maps using SPECT, PCASL with a simplified model, PCASL with a one-compartment model, and PCASL with one-compartment model using gray matter δa only, respectively. The images have been averaged across subjects (N=10). (b) Gray matter to white matter CBF ratio. The gray/white ratio with the simplified model was significantly greater than SPECT (P<0.005). That of the one-compartment model using gray matter δa only was smaller than SPECT (P<0.001). The results using one-compartment model with tissue specific δa were not different from SPECT (P=0.74). Error bars indicate the standard deviations across subjects.

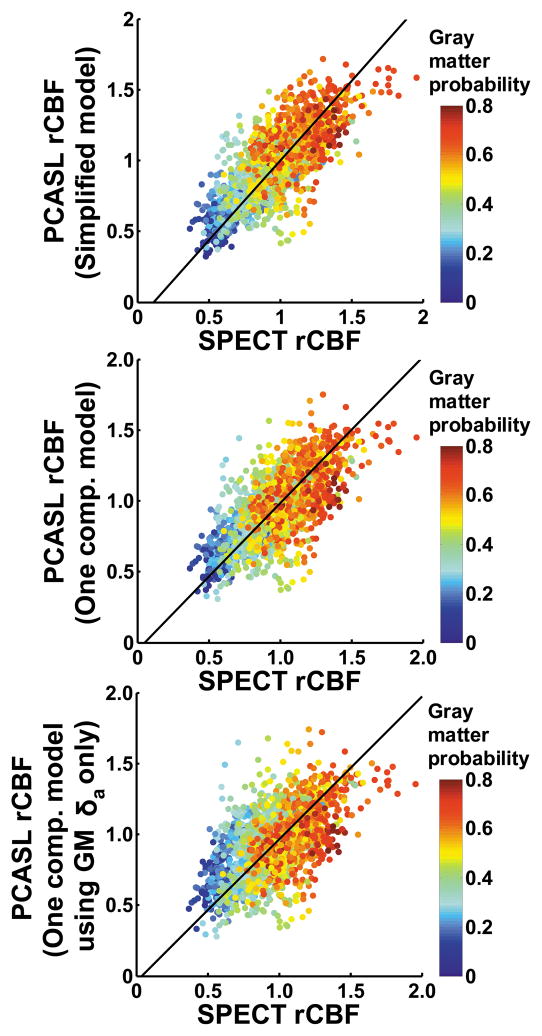

Scatter plots between SPECT and each of the PCASL rCBF maps are shown in Figure 4. The slopes for the fitting curves were 1.13, 1.04, and 1.01, respectively. The mean difference index, D, between SPECT and PCASL maps was 0.26, 0.27, and 0.29, respectively.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot between group-averaged SPECT and PCASL rCBF maps. The rCBF maps were down-sampled to a voxel size of 10×10×10 mm3 in accordance with their intrinsic spatial resolution. The color of the symbols represents the gray matter probability of individual voxel, demonstrating that the gray matter voxels are distributed in the upper right corner whereas the white matter voxels are clustered in the lower left corner. The black line indicates the fitted curve.

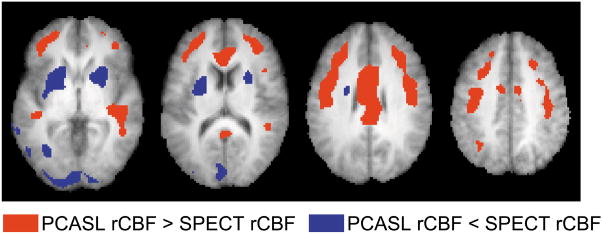

Figure 5 shows the results of voxel-wise statistical comparison between SPECT and one-compartment PCASL rCBF. It can be seen that, despite a general agreement between these two modalities, systematic differences are still present in certain brain regions.

Figure 5.

Brain regions showing significant differences between SPECT and PCASL rCBF maps. Voxels with P<0.001 and cluster size >1.6 cm3 are shown in color. Both positive and negative contrasts are shown.

Discussion

The present study aims to investigate model and parameter-related issues in PCASL quantification and to compare it to a radiotracer-based method. We first provided an estimation of an important kinetic parameter in ASL, the arterial transit time, for the white matter. Using these values for rCBF quantification, it was found that tissue-specific δa considerations can improve its correspondence to SPECT results and that the one-compartment model appears to provide a more accurate estimation of CBF compared to the simplified model. After accounting for these factors, the PCASL CBF maps were found to show good agreement with the SPECT method.

It is well known that arterial transit time is a key parameter in the calculation of CBF in ASL. Previous considerations on this topic have primarily focused on the gray matter, the transit time of which has been studied extensively with multi-delay continuous or pseudocontinuous ASL experiments and a range of values have been reported, e.g. Alsop et al. (~600 ms) (20), Ye et al. (~500 ms) (22), Gonzalez-At et al. (651–1200 ms) (21), Mildner et al. (~1600 ms) (23), Liu et al. (938±156 ms) (24). Other studies have measured transit time in Pulsed ASL methods (43–46). The gray matter transit time obtained in this study (912±209 ms) is in excellent agreement with a previous report using multiple delay times at similar slice locations (24).

For the white matter, our contrast agent approach estimated an averaged white matter transit time of 1541 ms, which is consistent with reports by van Gelderen et al. that the white matter transit time is 650 ms longer than that of the gray matter (47). Our values are longer than those measured with multi-delay methods, e.g. 350–1000 ms in Parkes and Toft. 2002, 700–1200 ms in Kimura et al. 2004, 1070–1490 ms in Qiu et al. 2010, and 990 ms in Kiziak et al. 2008. A possible reason for the discrepancy is that the gap between our labeling and imaging planes was 94 mm whereas the previous studies tended to use a smaller gap. Compared to previous contrast agent studies (47–49), we also used a higher temporal sampling rate (100 ms) which allowed the detection of small time differences across arteries and across sub-regions. For example, the Gd-DTPA bolus was found to arrive at the vertebral arteries later than internal carotid arteries, probably reflecting their differential vessel dimensions. The MCA perfusion territory was found to have an earlier bolus arrival compared to ACA and PCA regions, presumably again associated with the vessel sizes.

The simplified PCASL model assumes that T1 decay of the labeling follows the relaxation of the blood, while in reality the decay is faster due to the shorter tissue T1. Thus, the use of the simplified model generally results in an under-estimation of the CBF weighted signals. Furthermore, because white matter T1 is shorter than gray matter T1, the degree of under-estimation is greater for the white matter. Consequently, in terms of rCBF values, the gray matter is over-estimated while the white matter is under-estimated when the simplified model is used. In addition to the T1 differences among blood, gray and white matter, the time fraction in which the spins experience these T1’s is also an important factor, which is determined by δa. If the longer white matter δa is not accounted for, white matter CBF signal would be over-estimated. Then, in the rCBF map, white matter rCBF values will be over-estimated and the gray matter values will be under-estimated.

Several previous studies have compared earlier ASL methods to PET (26,50,51) and to SPECT (52). A recent report also compared the PCASL technique to a H215O PET method (53). While both the present study and the earlier study demonstrated a correlation between PCASL and radio-tracer methods, they are different in a number of aspects. First, the study of Xu et al. did not account for transit time differences between the gray and white matter. Instead, a simplified model of Chalela et al. (31) was used for quantification which assumed identical T1 values for blood and tissues. As shown in our results, the simplified model yielded less than optimal correspondence with the gold-standard method. Second, the sample size of the earlier study was relatively small and also included a mixture of patients and controls. Finally, the PET/PCASL comparison of Xu et al. was conducted in elderly subjects and the effect of brain atrophy on the validation results was not clear.

Our data suggest that PCASL quantification may benefit from using a more realistic model, in which the model parameters, e.g. T1, T2*, λ and δa, are varied on a voxel-by-voxel basis using assumed values for pure gray and white matter together with tissue probability from high-resolution T1-weighted image. One contribution of this work is the determination of δa in the white matter. However, we do not recommend the measurement of δa for each subject who undergoes ASL scan, because the procedure requires the use of exogenous contrast agent, which nullifies the advantage of the convenience of ASL. One can also divide the tissue into subregions (e.g. based on flow territory) and use region-specific (in addition to tissue-specific) δa values listed in Table 2. This strategy would, however, require additional assumptions on flow territory maps and would also be susceptible to errors associated with normal variations in cerebral arteries of the Circle of Willis (34). We also recognize that different slices may have different δa, thus the use of a single δa value for one tissue type cannot account for this variation. We note, however, that the across-slice differences (24) are expected to be smaller than the gray/white differences (47). In our opinion, a tradeoff strategy is to use model parameters based on tissue probability to achieve best possible estimation while acknowledging that systematic bias could still be present due to imperfection in model and parameter considerations (24,25,54–56).

The findings from the present study should be interpreted in view of a few limitations. First, the two components of the study were conducted on separate cohorts. Should the experiments be performed on the same subjects, the δa values obtained in the bolus-tracking study would have been more relevant for the PCASL quantification and an improved correspondence between PCASL and SPECT may be observed. The study will also benefit from a direct comparison between transit times determined with bolus-tracking and those from multi-delay ASL. Second, as the SPECT method used in the present study did not employ arterial sampling, it was not possible to obtain absolute CBF values. On the other hand, as stated at the beginning of this report, alternative methods are available for the relative-to-absolute conversion and the goal of the present study was to identify an optimal approach to estimate a relative CBF map. Another limitation is that our study has primarily focused on healthy control subjects, but no patient populations were included. Patients with cerebrovascular diseases may have longer arterial transit times (57). In these patients, a bolus-tracking transit time measurement is recommended for accurate CBF estimation. Alternatively, one can lengthen the post-labeling delay time (e.g. to 2.5–3 seconds) in ASL to ensure a full arrival of the labeled spins. This is, however, achieved at the cost of the SNR of the data. Finally, the calculation of rCBF used a number of assumptions based on relaxation parameters in the literature (42,58,59). We have also tested to use values in other reports (60,61), and found that the findings were qualitatively comparable.

Conclusions

The present study determined arterial transit time in brain tissue using a bolus-tracking approach. White matter transit time was found to be significantly greater than that of the gray matter. The use of tissue-specific model parameters was helpful in improving the correspondence between PCASL and SPECT results. One-compartment PCASL model yielded more accurate estimation of rCBF, compared to a simplified model. Despite the need for further improvement in its quantification, PCASL-derived rCBF after accounting for transit time offers an excellent choice for a fast, convenient, and noninvasive measurement of perfusion in the human brain.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Jacquelyn Braud, Thomas Harris, and Rani Varghese for assistance with the experiments, and to Matthias van Osch for providing the PCASL pulse sequence.

Grant sponsors: NIH R01 DA023203 (to BA), NIH R01 MH084021 (to HL), NIH R01 NS067015 (to HL), NIH R21 EB007821 (to HL), and American Heart Association 0865003F (to HL).

Abbreviations used

- PCASL

Pseudo-continuous arterial spin labelin

- SPECT

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- rCBF

relative cerebral blood flow

- DSC

dynamic susceptibility contrast

- ACA

anterior cerebral arteries

- MCA

middle cerebral arteries

- PCA

posterior cerebral arteries

- ICA

internal carotid arteries

References

- 1.Luh WM, Wong EC, Bandettini PA, Hyde JS. QUIPSS II with thin-slice TI1 periodic saturation: a method for improving accuracy of quantitative perfusion imaging using pulsed arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:1246–1254. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199906)41:6<1246::aid-mrm22>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsop DC, Detre JA. Multisection cerebral blood flow MR imaging with continuous arterial spin labeling. Radiology. 1998;208:410–416. doi: 10.1148/radiology.208.2.9680569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai W, Garcia D, de Bazelaire C, Alsop DC. Continuous flow-driven inversion for arterial spin labeling using pulsed radio frequency and gradient fields. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:1488–1497. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong EC. Vessel-encoded arterial spin-labeling using pseudocontinuous tagging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1086–1091. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detre JA, Leigh JS, Williams DS, Koretsky AP. Perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1992;23:37–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910230106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SG. Quantification of relative cerebral blood flow change by flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery (FAIR) technique: application to functional mapping. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:293–301. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams DS, Detre JA, Leigh JS, Koretsky AP. Magnetic resonance imaging of perfusion using spin inversion of arterial water. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:212–216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong EC, Buxton RB, Frank LR. Implementation of quantitative perfusion imaging techniques for functional brain mapping using pulsed arterial spin labeling. NMR Biomed. 1997;10:237–249. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199706/08)10:4/5<237::aid-nbm475>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong EC, Buxton RB, Frank LR. Quantitative imaging of perfusion using a single subtraction (QUIPSS and QUIPSS II) Magn Reson Med. 1998;39:702–708. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trampel R, Mildner T, Goerke U, Schaefer A, Driesel W, Norris DG. Continuous arterial spin labeling using a local magnetic field gradient coil. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:543–546. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez-Seara MA, Aznarez-Sanado M, Mengual E, Loayza FR, Pastor MA. Continuous performance of a novel motor sequence leads to highly correlated striatal and hippocampal perfusion increases. Neuroimage. 2009;47:1797–1808. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim J, Wu WC, Wang J, Detre JA, Dinges DF, Rao H. Imaging brain fatigue from sustained mental workload: an ASL perfusion study of the time-on-task effect. Neuroimage. 2010;49:3426–3435. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarnum H, Steffensen EG, Knutsson L, Frund ET, Simonsen CW, Lundbye-Christensen S, Shankaranarayanan A, Alsop DC, Jensen FT, Larsson EM. Perfusion MRI of brain tumours: a comparative study of pseudo-continuous arterial spin labelling and dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging. Neuroradiology. 2010;52:307–317. doi: 10.1007/s00234-009-0616-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson NA, Jahng GH, Weiner MW, Miller BL, Chui HC, Jagust WJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Schuff N. Pattern of cerebral hypoperfusion in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment measured with arterial spin-labeling MR imaging: initial experience. Radiology. 2005;234:851–859. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2343040197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfefferbaum A, Chanraud S, Pitel AL, Muller-Oehring E, Shankaranarayanan A, Alsop DC, Rohlfing T, Sullivan EV. Cerebral Blood Flow in Posterior Cortical Nodes of the Default Mode Network Decreases with Task Engagement but Remains Higher than in Most Brain Regions. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:233–244. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yezhuvath US, Uh J, Cheng Y, Martin-Cook K, Weiner M, Diaz-Arrastia R, van Osch M, Lu H. Forebrain-dominant deficit in cerebrovascular reactivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.1002.1005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aslan S, Xu F, Wang PL, Uh J, Yezhuvath US, van Osch M, Lu H. Estimation of labeling efficiency in pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:765–771. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonekamp D, Degaonkar M, Barker PB. Quantitative cerebral blood flow in dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI using total cerebral flow from phase contrast magnetic resonance angiography. Magn Reson Med. 2011 doi: 10.1002/mrm.22776. In-press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Osch MJ, Teeuwisse WM, van Walderveen MA, Hendrikse J, Kies DA, van Buchem MA. Can arterial spin labeling detect white matter perfusion signal? Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:165–173. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alsop DC, Detre JA. Reduced transit-time sensitivity in noninvasive magnetic resonance imaging of human cerebral blood flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:1236–1249. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199611000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez-At JB, Alsop DC, Detre JA. Cerebral perfusion and arterial transit time changes during task activation determined with continuous arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43:739–746. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200005)43:5<739::aid-mrm17>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye FQ, Mattay VS, Jezzard P, Frank JA, Weinberger DR, McLaughlin AC. Correction for vascular artifacts in cerebral blood flow values measured by using arterial spin tagging techniques. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37:226–235. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mildner T, Moller HE, Driesel W, Norris DG, Trampel R. Continuous arterial spin labeling at the human common carotid artery: the influence of transit times. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:19–23. doi: 10.1002/nbm.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu P, Uh J, Lu H. Determination of spin compartment in arterial spin labeling MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:120–127. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parkes LM, Tofts PS. Improved accuracy of human cerebral blood perfusion measurements using arterial spin labeling: accounting for capillary water permeability. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:27–41. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu M, Paul Maguire R, Arora J, Planeta-Wilson B, Weinzimmer D, Wang J, Wang Y, Kim H, Rajeevan N, Huang Y, Carson RE, Constable RT. Arterial transit time effects in pulsed arterial spin labeling CBF mapping: insight from a PET and MR study in normal human subjects. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:374–384. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koziak AM, Winter J, Lee TY, Thompson RT, St Lawrence KS. Validation study of a pulsed arterial spin labeling technique by comparison to perfusion computed tomography. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26:543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura H, Kabasawa H, Yonekura Y, Itoh H. Cerebral perfusion measurements using continuous arterial spin labeling: accuracy and limits of a quantitative approach. International Congress Series. 2004;1265:238–247. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu WC, Fernandez-Seara M, Detre JA, Wehrli FW, Wang J. A theoretical and experimental investigation of the tagging efficiency of pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1020–1027. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luh WM, Wong EC, Bandettini PA. How Long to Tag? Optimal Tag Duration for Arterial Spin Labeling at 1.5T, 3T, and 7T. Proceedings of the ISMRM 17th Annual Meeting; Toronto, ON, Canada. 2008. p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chalela JA, Alsop DC, Gonzalez-Atavales JB, Maldjian JA, Kasner SE, Detre JA. Magnetic resonance perfusion imaging in acute ischemic stroke using continuous arterial spin labeling. Stroke. 2000;31:680–687. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okell TW, Chappell MA, Woolrich MW, Gunther M, Feinberg DA, Jezzard P. Vessel-encoded dynamic magnetic resonance angiography using arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:698–706. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woolsey TA, Hanaway J, Gado MH. The Brain Atlas: A Visual Guide to the Human Central Nervous System. 2. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Laar PJ, Hendrikse J, Golay X, Lu H, van Osch MJ, van der Grond J. In vivo flow territory mapping of major brain feeding arteries. Neuroimage. 2006;29:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendrikse J, van der Grond J, Lu H, van Zijl PC, Golay X. Flow territory mapping of the cerebral arteries with regional perfusion MRI. Stroke. 2004;35:882–887. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000120312.26163.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adinoff B, Devous MD, Sr, Williams MJ, Best SE, Harris TS, Minhajuddin A, Zielinski T, Cullum M. Altered neural cholinergic receptor systems in cocaine-addicted subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1485–1499. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Rocco RJ, Silva DA, Kuczynski BL, Narra RK, Ramalingam K, Jurisson S, Nunn AD, Eckelman WC. The single-pass cerebral extraction and capillary permeability-surface area product of several putative cerebral blood flow imaging agents. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:641–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murase K, Tanada S, Inoue T, Ochi K, Fujita H, Sakaki S, Kimura Y, Hamamoto K. Measurement of the blood-brain barrier permeability of I-123 IMP, Tc-99m HMPAO and Tc-99m ECD in the human brain using compartment model analysis and dynamic SPECT. J Nucl Med. 1991;32:911. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuchida T, Yonekura Y, Nishizawa S, Sadato N, Tamaki N, Fujita T, Magata Y, Konishi J. Nonlinearity correction of brain perfusion SPECT based on permeability-surface area product model. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1237–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuikka JT, Lansimies E, Kuikka EO. Quantitative analysis of 99mTc-HMPAO kinetics in epilepsy. Eur J Nucl Med. 1990;16:275–283. doi: 10.1007/BF00842780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu H, Clingman C, Golay X, van Zijl PC. Determining the longitudinal relaxation time (T1) of blood at 3.0. Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:679–682. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uh J, Lin AL, Lee K, Liu P, Fox P, Lu H. Validation of VASO cerebral blood volume measurement with positron emission tomography. Magn Reson Med. 2010 doi: 10.1002/mrm.22667. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hendrikse J, Petersen ET, van Laar PJ, Golay X. Cerebral border zones between distal end branches of intracranial arteries: MR imaging. Radiology. 2008;246:572–580. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461062100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buxton RB, Frank LR, Wong EC, Siewert B, Warach S, Edelman RR. A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40:383–396. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Y, Engelien W, Xu S, Gu H, Silbersweig DA, Stern E. Transit time, trailing time, and cerebral blood flow during brain activation: measurement using multislice, pulsed spin-labeling perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:680–685. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200011)44:5<680::aid-mrm4>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hendrikse J, Lu H, van der Grond J, Van Zijl PC, Golay X. Measurements of cerebral perfusion and arterial hemodynamics during visual stimulation using TURBO-TILT. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:429–433. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Gelderen P, de Zwart JA, Duyn JH. Pittfalls of MRI measurement of white matter perfusion based on arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:788–795. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butman JA, Rebmann AJ, Talagala SL. Measurement of reginal cervical-cerebral transit time at high temporal resolution using dynamic susceptibility contrast. Proceedings of the ISMRM 10th Annual Meeting; 2002. p. 1076. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ibaraki M, Shimosegawa E, Toyoshima H, Ishigame K, Ito H, Takahashi K, Miura S, Kanno I. Effect of regional tracer delay on CBF in healthy subjects measured with dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MRI: comparison with 15O-PET. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2005;4:27–34. doi: 10.2463/mrms.4.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ye FQ, Berman KF, Ellmore T, Esposito G, van Horn JD, Yang Y, Duyn J, Smith AM, Frank JA, Weinberger DR, McLaughlin AC. H(2)(15)O PET validation of steady-state arterial spin tagging cerebral blood flow measurements in humans. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:450–456. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200009)44:3<450::aid-mrm16>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bokkers RP, Bremmer JP, van Berckel BN, Lammertsma AA, Hendrikse J, Pluim JP, Kappelle LJ, Boellaard R, Klijn CJ. Arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI at multiple delay times: a correlative study with H(2)(15)O positron emission tomography in patients with symptomatic carotid artery occlusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:222–229. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Noguchi T, Kawashima M, Irie H, Ootsuka T, Nishihara M, Matsushima T, Kudo S. Arterial spin-labeling MR imaging in moyamoya disease compared with SPECT imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.016. In-press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu G, Rowley HA, Wu G, Alsop DC, Shankaranarayanan A, Dowling M, Christian BT, Oakes TR, Johnson SC. Reliability and precision of pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI on 3.0 T and comparison with 15O-water PET in elderly subjects at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. NMR Biomed. 2010;23:286–293. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang J, Alsop DC, Li L, Listerud J, Gonzalez-At JB, Schnall MD, Detre JA. Comparison of quantitative perfusion imaging using arterial spin labeling at 1.5 and 4.0 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:242–254. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petersen ET, Lim T, Golay X. Model-free arterial spin labeling quantification approach for perfusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:219–232. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petersen ET, Mouridsen K, Golay X. The QUASAR reproducibility study, Part II: Results from a multi-center Arterial Spin Labeling test-retest study. Neuroimage. 2010;49:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaharchuk G, Straka M, Marks MP, Albers GW, Moseley ME, Bammer R. Combined arterial spin label and dynamic susceptibility contrast measurement of cerebral blood flow. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:1548–1556. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herscovitch P, Raichle ME. What is the correct value for the brain--blood partition coefficient for water? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985;5:65–69. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1985.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu H, Nagae-Poetscher LM, Golay X, Lin D, Pomper M, van Zijl PC. Routine clinical brain MRI sequences for use at 3.0 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:13–22. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wansapura JP, Holland SK, Dunn RS, Ball WS., Jr NMR relaxation times in the human brain at 3.0 tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9:531–538. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199904)9:4<531::aid-jmri4>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gelman N, Ewing JR, Gorell JM, Spickler EM, Solomon EG. Interregional variation of longitudinal relaxation rates in human brain at 3.0 T: relation to estimated iron and water contents. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45:71–79. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200101)45:1<71::aid-mrm1011>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]