Abstract

Brain injury begins early after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Although cell death via apoptosis and necrosis is known to be present in brain 24 hours after SAH, it is not known how soon after SAH cell death begins. We have previously described structural changes in rat brain microvessels 10 minutes after induction of SAH by endovascular puncture. This study examined brain for evidence of cell death beginning 10 minutes after induction of SAH. Cleaved caspase-3 (cl-caspase-3) staining was evident in vascular and parenchymal cells at 10 minutes after SAH and was significantly greater than in time-matched, sham-operated controls. The number of cl-caspase-3 positive cells was increased further at 24 hour after SAH. TUNEL assay revealed apoptotic cells present at 10 minutes, with substantially more at 24 hours after SAH. Scattered Fluoro-Jade positive neurons appeared at 1 hour after SAH and their number increased with time. At 1 hour Fluoro-Jade positive neurons were present in cortical and subcortical regions but not in hippocampus; at 24 hours they were also present in hippocampus and were significantly greater in the hemisphere ipsilateral to the vascular puncture. No Fluoro-Jade staining was present in shams. These data demonstrate an early activation of endothelial and parenchymal cells apoptosis and neuronal necrosis after SAH and identifies endpoints that can be targeted to reduce early brain injury after SAH.

Keywords: Subarachnoid hemorrhage, Early injury, Apoptosis, Necrosis, Caspase-3, Cleaved caspase-3, Non-apoptotic caspase-3

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) accounts for 5% of all stroke cases. Approximately 12% of patients die before receiving medical attention, 33% within 48 hours and 50% within 30 days of SAH [1, 11]. Brain injury begins at the rupture of aneurysm, evolves with time and plays an important role in the overall outcome [22].

Stress and death of brain cells, including necrosis, apoptosis, and autophagy, are known to be present at 24 hours after SAH [3, 14, 16, 25, 26]; however, it is not known how soon after SAH cell death begins. We have previously reported adhesion of platelet aggregates and initiation of microvascular damage as early as 10 minutes after SAH [6, 21]. The present study demonstrates that cell death has also begun at 10 minutes after SAH, increases subsequently, and includes both vascular and neuronal elements.

All experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mount Sinai Medical Center. SAH was induced in 3-month-old male Sprague-Dawley rats using endovascular suture [2]. Three month old male rats were anesthetized with single intra-peritoneal bolus ketamine-xylazine injection (80 +10 mg / kg), transorally intubated, and maintained on inspired isoflourane (0.5–1%). Body temperature was maintained at 37°C by homeothermic blanket. Blood pressure (BP) and blood gas were measured by cannulating the right femoral artery (ABL5, Radiometer America, USA). Intracranial pressure (ICP) was measured by implanting a cannula in the cistern magna, and cerebral blood flow (CBF) was measured with a Laser-Doppler probe (Vasamedics, Inc., USA) placed over the skull away from large pial vessels in the distribution of the middle cerebral artery.

To induce SAH, a suture was advanced retrogradely through the ligated right external carotid artery, and distally through the internal carotid artery (ICA) until the suture perforated the intracranial bifurcation of the right ICA. Animals were returned to their cages as they regained consciousness and sacrificed at 10 minutes, 1, 3, 6, or 24 hours after SAH.

Sham-operated animals were used as controls. Sham surgery included all steps described above for SAH induction, including the advance of a suture through the ligated external carotid artery; however the internal carotid artery was not perforated and no hemorrhage occurred. Sham animals were sacrificed at 10 minutes or 24 hours after surgery.

Animals were assigned randomly to SAH or sham groups (N= 5 per time interval per SAH and Sham surgery). ICP, CBF, and BP were recorded in real time before, during and after surgery to ensure that all animals had comparable SAH severity. The average baseline ICP was 5.5±0.5 mmHg; following SAH it peaked at 52.0±3.5 mmHg. The average CBF fell following SAH to 10.1±1.7% of baseline, with recovery at 60 minutes to 44.9±8.4% of baseline. BP increased at SAH and returned to the baseline within ten minutes. The ICP and CBF values indicate that rats experienced moderate SAH [2]. Four animals died within 24 hours after SAH induction; these were replaced in the study to keep the number of animals constant at 5 per group.

For sacrifice, anesthetized animals were perfused transcardially with chilled saline. Brains were rapidly removed, embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound, and frozen in 2-methylbutane cooled in dry ice. Coronal brain sections (8 μm thick) were cut on a cryostat and thaw-mounted onto gelatin-coated slides. Sections located at bregma +0.2 and − 3.6 mm [15] were used.

Primary antibodies included: rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175; Cell Signaling Technology Inc. USA); goat anti-collagen IV, a major protein of vascular basement membrane; Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc. USA); mouse monoclonal anti-rat endothelial cell antigen (RECA-1, an endothelial marker of blood-brain barrier; Serotec Inc. USA), and mouse monoclonal anti-neuronal nuclei (NeuN; Chemicon International, Inc. USA). Secondary antibodies were: species-specific donkey anti-goat Alexa 647 (Invitrogen Corp. USA), donkey anti-mouse Alexa 488 (Invitrogen Corp., USA), and donkey anti-rabbit Rhodamine Red X (Jackson Immuno. Research, USA).

For immunostaining, frozen brain sections were thawed and fixed for 15 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Sections were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), blocked in a solution of 3% normal donkey serum in PBS, and incubated overnight at 4°C in combinations primary antibodies diluted as follows in blocking solution: anti-cleaved caspase-3 (cl-caspase-3), 1:250; anti-NeuN, 1;200; anti-RECA-1, 1:100; and anti-collagen IV, 1:200. Sections were washed with PBS, incubated overnight at 4°C with species-specific secondary antibodies in blocking solution, washed with PBS, and coverslipped with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (stains nuclei; Vector labs, USA).

For TUNEL, the Roche In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit was used (POD; Roche Applied Science, USA). Briefly, PFA fixed sections were incubated in permeabilization solution for 10 minutes followed by TUNEL reaction mixture at 37°C for one hour. Some sections were subsequently immunostained for cl-caspase-3 as described above.

For Fluoro-Jade B staining, air dried sections were incubated in 100% ethanol for 3 minutes and 70% ethanol for 1 minute and then washed with demonized water. Sections were then incubated for 10 minutes in 0.06% potassium permanganate for 10 minutes followed by 30 minutes in Fluoro-Jade B solution (Histo-Chem, Inc., USA) with added DAPI (0.0004%). Sections were dried overnight at room temperature, cleared with xylene, and coverslipped using DPX (Electron Microscopy Sciences Inc.USA).

Basal, frontal and convexity cerebral cortex; caudate-putamen, thalamus and hippocampus [15] regions were analyzed for cl-caspase-3, TUNEL and Fluoro-Jade B staining using widefield (Zeiss AxioPlan 2ie) and confocal (Leica TCS-SP5) microscopes. Quantitative analysis was performed on widefield images recorded under constant illumination and exposure conditions using a 20X objective lens, yielding an image area of 8 × 104 um2 per field.

Quantitation used IPLab software (Scanalytic Inc, v3.63; USA) and was performed by an observer blinded to specimen identity. Signal-positive profiles were delineated in each fluorescence channel separately by intensity threshold segmentation with particle size gating, and numbers of profiles positive singly for each channel and for combinations of channels (depending on the fluorescent stain combination) were recorded.

Each parameter (numbers of cl-caspase-3, TUNEL or Fluoro-Jade positive cells) was analyzed by two-way ANOVA (StatView v. 5.0.1, SAS Institute Inc. USA) with factors survival time and treatment (sham control, SAH). Pairwise comparisons used Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc tests. Counts are expressed as average ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m)

Cl-caspase-3 immunostaining was present in brain at 10 minutes after SAH (Figure-1A; image). Cl-caspase-3 positive cells were scattered throughout cortical and subcortical regions excepthippocampus. Cl-caspase-3 positive cells could also be seen at 10 minutes survival within in the subarachnoid space, surrounding extravasated blood. At 24 hours, positive cells were also present in the hippocampus (Figure-1B).

The number of cl-caspase-3 positive cells increased progressively from 10 minutes to 6 and 24 hours after SAH. No hemispheric difference in cl-caspase-3 staining in SAH animals was found (F=1.25, P=0.26).

We also observed some cl-caspase-3 cells in sham-operated controls. This result is consistent with our previous finding of increased collagenase activity in sham-operated as compared to naïve animals [20] and likely reflects the effects of the major surgery which the sham-operated controls have undergone. Quantitative differences between sham-operated and SAH animals are, we believe, accurate measures of the effects of SAH independent of the experimental surgery.

We investigated the identity of cl-caspase-3 positive cells by immunostaining for cl-caspase-3, NeuN and collagen IV together. Of cl-caspase-3 positive cells, more than 50% were also positive for NeuN and are therefore identified as neurons. A further 20% were NeuN-negative but were positive for collagen IV and are identified as vascular cells (Figure-1A &B). A third population was stained for cl-caspase-3 but not for either NeuN or collagen IV (Figure-1A); those cells remain to be identified.

We counted the cl-caspase-3 positive cells that colocalized with RECA-1, an endothelial marker (Figure 1C). A significantly greater number of vascular cells contained cl-caspase-3 staining at 10 minutes after SAH compared to time matched sham cohorts (P<0.05). That cell number increased further from 6–24 hours after SAH and remained significantly greater than in sham animals (P<0.05; Figure 1C). TUNEL positive cells were evenly distributed across hemispheres at 10 minutes (P>0.05) but were significantly greater in the right hemisphere (ipsilateral to the hemorrhage) at 24 hours post SAH (P=0.02).

Figure 1.

Caspase-3 activation after SAH. A: a typical field from cerebral cortex at 10 minutes after SAH, showing immonofluorescence for cl-caspase-3 (left panel), collagen IV (center panel) and NeuN (right panel). Thin arrows: profiles positive for collage IV and cl-caspase-3 but not for NeuN, showing caspase-3 activation in microvasculature. Thick arrows: profiles positive for cl-caspase-3 and NeuN and negative for collagen IV show caspase activation in neurons. Arrowheads: profiles positive for cl-caspase-3 but negative for both collagen IV and NeuN reveal cl-caspase-3 activation in nonneuronal, nonvascular cells. B: hippocampus at 24 hours after SAH, stained and marked as in panel A, showing the same three phenotypes as in A. C: number of vascular (collage IV-positive, left) and total (right) cells positive for cl-caspase-3 positive at different survival times. Both categories show progressive increases with time. Data are mean ± sem, N = 5 animals per time point. * significantly different from time-matched sham value (p<0.05); ! significantly different from the earliest SAH value (p<0.05).

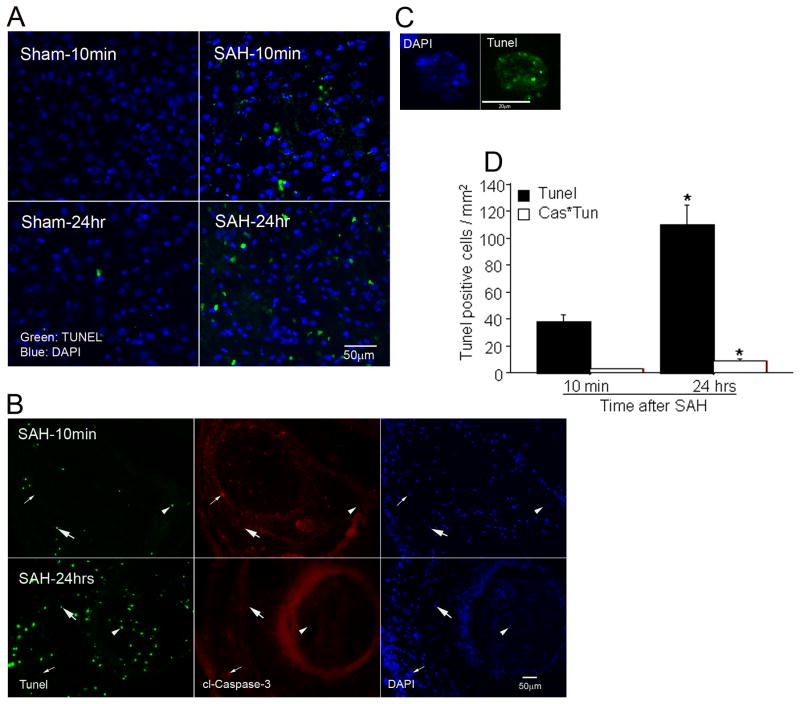

Recent studies indicate that cells positive for cl-caspase-3 are not always destined to die; non-apoptotic cl-caspase-3 also exists [19, 24]. We combined TUNEL stain with cl-caspase-3 immunostaining to determine the extent to which TUNEL stain colocalized with cl-caspase-3. At 10 minutes survival, we found TUNEL-stained cells scattered in brain parenchyma and also in subarachnoid space, adjacent to accumulations of blood (Figure-2A &B). The number of parenchymal TUNEL positive cells was significantly increased at 24 hours (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Cell death after SAH. A: TUNEL staining of cerebral cortex at 10 minutes and 24 hours after SAH. Marked TUNEL activity is visible in some cells at 10 minutes after SAH, with an increase in the number of positive cells at 24 hours. B: simultaneous TUNEL and anti-cl-caspase-3 staining of subarachnoid blood. Some TUNEL positive cells are positive for cl-caspase-3 as well (thick arrow) but many are not (arrowhead). In addition, many caspase-3 positive cells are not positive for TUNEL (thin arrow). The broad red ring reflects unspecific binding of primary antibody in regions of high serum protein concentration; specific cl-caspace-3 labeling displays as small dots in this figure. C: a typical apoptotic cell displaying chromatin clumping and foci of TUNEL labeling. D: numbers of total TUNEL positive cells (Tunel) and TUNEL positive, cl-caspase-3 positive cells (Cas*Tun). Cl-caspase-3 was present in only a small fraction of TUNEL positive cells. Data are mean ± sem of counts from the five regions studied; N = 5 animals per group. * p< 0.05.

Not all TUNEL positive cells were costained with cl-caspase-3 (Figure-2D). The number of cl-caspase-3 and TUNEL costained cells increased at 24 hours but remained significantly smaller than total caspase-3 or total TUNEL stained cells. The identity of TUNEL stained cells was established by combining TUNEL with collagen IV and NeuN immunostaining. The brain specimens from animals sacrificed at 10 minutes and 24 hour SAH were used. As expected most TUNEL positive cells were either vascular or neuronal. At 10 minutes after SAH, 4% of neurons and 10 % of collagen IV positive vessels contained TUNEL staining. By 24 hours after SAH, TUNEL staining had increased to 14 % of NeuN-postive cells and had decreased to 3% of collagen IV positive vessels.

Next we investigated whether neurodegeneration contributes to early cell death after SAH. Brain specimens from SAH and sham animals sacrificed at 10 minutes, 1, 3, or 24 hours after surgery were used and stained with Fluoro-Jade B, a marker of neurodegeneration. No Fluoro-Jade positive cells were present at 10 minutes after SAH. At one hour, Fluoro-Jade stained cell profiles were clearly visible in cortical regions except hippocampus and in subcortical regions; at three hours profiles were increased in number (Figure-3A). Fluoro-Jade positive neurons were present in hippocampus and the other regions at 24 hours. No Fluoro-Jade staining was present in sham operated animals. Quantitative analysis verified that Fluoro-Jade positive cells increased progressively with time after SAH (Figure-3B).

We further investigated whether cell death via apoptosis and degeneration occur together. Adjacent brain specimens from animals sacrificed 24 hour after SAH were stained for cl-caspase-3 and TUNEL or with Fluoro-Jade B. We found that Fluoro-Jade staining was present in the brain areas that were positive for cl-caspase-3 and TUNEL staining (Figure-4A and B). On average, Fluoro-Jade stained profiles were more numerous than were TUNEL positive profile in these brain regions.

Injury which contributes to early deaths and brain injury after SAH appears to be ischemic in nature. Experimental microdialysis studies demonstrate that ischemia develops within minutes after SAH [2, 18]. Ischemic changes are found in the brains of patients who died at various time intervals starting 10 minutes after SAH [8]. Experimental studies demonstrate that brain cells express stress signals such as the immediate early genes c-jun and c-fos, hemeoxygenase-1, and heat shock protein within minutes to hours after SAH [10, 12]. Cells expressing stress signals after SAH include neurons, glia and endothelium [10, 12]. Death of brain cells is found 24 hours after SAH and involves apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy [3, 14, 16, 26]. A variety of pathways are implicated in apoptotic cell death after SAH and their inhibition pre or 30–60 minutes post SAH is found to limit cell death and increase survival [4, 7, 9]. Our results, demonstrating that cell death is activated within 10 minutes after SAH provide an explanation as to why an early use is required to get most benefits from an anti-apoptotic agent.

Caspase-3 activation is a crucial step in the process of apoptosis. Caspase-3 is a member of the cysteine-aspartic acid protease family that is activated by proteolytic cleavage by caspases 8, 9, and 10 and cleaves and activates caspases 6 and 7. Activation of caspase-3 is essential for cell execution and occurs immediately (5 minutes or less) before the development of morphological changes consistent with apoptosis [23]. Hence, traditionally, a cell with activated caspase-3 is considered destined to die. Contrary to this concept are the recent findings showing that caspase-3 has several non-apoptotic functions in cells (such as proliferation, differentiation and cell cycle regulation, etc) and that caspase-3 does not always kill the cell that expresses it [19]. In the present study, we find that caspase-3 activates very early (within 10 minutes) after SAH. In addition we find that, although a large number of cells express cl-caspase-3 during the first 24 hours after SAH, only one third undergo apoptosis as revealed by TUNEL staining. Moreover, of the cells undergoing apoptosis less than 10% contain activated caspase-3. Hence, it appears that caspase-3 activation early after SAH does not necessarily mark a cell for death. Similar findings were reported recently in ischemic stroke [24] . In that study most of the cl-caspase-3 expressed two to four days after ischemic stroke did not colocalize with TUNEL. They concluded that caspase-3 expression was predominantly non-apoptotic and was associated with cellular responses to stroke such as reactive astrogliosis and the infiltration of macrophages. Non-apoptotic functions of cl-caspase-3 in SAH brains are yet to be identified.

In the present study we found cells containing cl-caspase-3 and TUNEL reactivity within 10 minutes after SAH; however it took at least one hour for profiles positive for Fluoro-Jade to appear. This pattern suggests that, of the two modes of cell death, apoptosis is the first to activate. Glutamate-induced excitotoxicity may be one mechanism of neurodegeneration after SAH. In this regard it is pertinent to note that the interstitial glutamate concentration increases minutes after SAH and peaks at 40 minutes [2].

Cell death by apoptosis and necrosis can be differentiated by morphological and biochemical differences. The present study finds that at least two modes of cell death are active at the same time after SAH. Previous studies have shown that, since apoptosis is energy dependent, cell death is changed from apoptosis to necrosis when cells are depleted of adenosine triphosphate; this results in a cell population in which death is occurring by apoptosis as well as necrosis [5, 13]. A number of studies suggest that energy depletion occurs early after SAH. Animal and human cerebral microdialysis studies show that glycolysis becomes anaerobic and lactate/pyruvate ratio increases early after SAH and associates with poor outcome [17, 18].

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that biochemical events associated with cell death in brain begins very early after SAH, and provides a rationale for exploring early intervention following SAH with agents that inhibit apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Neurodegeneration after SAH. A: Fluoro-Jade staining of caudate-putamen. Stained cell bodies are not seen at 10 minutes after SAH, are present but sparse at 1 hour, and increase in number thereafter. B: numbers Fluoro-Jade B positive neurons in right hemisphere. Data are mean ± sem of counts from the five regions studied; N = 5 animals per group. *p< 0.05.

Figure 4.

Apoptosis and neurodegenration 24 hours after SAH. A: TUNEL and cl-caspase-3 in cerebral cortex (left panel), and Fluoro-Jade B staining in the same region of an adjacent section (right panel) show that both apoptosis and neurodegeneration occur simultaneously. B: adjacent sections of hippocampus, prepared as in panel A. The TUNEL-positive locus is strongly stained by Fluoro-Jade B.

Highlights.

Caspase-3 activates and DNA fragmentation begins in endothelial cells and in neurons within ten minutes after SAH.

Only one third of cells positive for active caspease-3 undergo apoptosis.

Necrosis (Fluoro-Jade B staining) begins one hr after SAH.

Apoptosis and necrotic cell death occurs concurrently in brain after SAH.

These results emphasize the importance of early management to limit injury after SAH.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the American Heart Association (GRNT4570012, FAS) and the National Institutes of Health (RO1 NS050576; FAS). Microscopy was performed at the MSSM Microscopy Shared Resource Facility.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bederson JB, Connolly ES, Jr, Batjer HH, Dacey RG, Dion JE, Diringer MN, Duldner JE, Jr, Harbaugh RE, Patel AB, Rosenwasser RH. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40:994–1025. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.191395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bederson JB, Levy AL, Ding WH, Kahn R, DiPerna CA, Jenkins ALr, Vallabhajosyula P. Acute vasoconstriction after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:352–360. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199802000-00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cahill J, Calvert JW, Solaroglu I, Zhang JH. Vasospasm and p53-induced apoptosis in an experimental model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2006;37:1868–1874. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000226995.27230.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen G, Fang Q, Zhang J, Zhou D, Wang Z. Role of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in early brain injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:515–523. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eguchi Y, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y. Intracellular ATP levels determine cell death fate by apoptosis or necrosis. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1835–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedrich V, Flores R, Muller A, Sehba FA. Escape of intraluminal platelets into brain parenchyma after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neuroscience. 2010;165:968–975. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao C, Liu X, Liu W, Shi H, Zhao Z, Chen H, Zhao S. Anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective effects of Tetramethylpyrazine following subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Auton Neurosci. 2008;141:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammes EMJ. Reaction of the meninges to blood. Ach Neurol Psychiatry. 1944;52:505–514. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasegawa Y, Suzuki H, Altay O, Zhang JH. Preservation of tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB) signaling by sodium orthovanadate attenuates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Stroke. 2011;42:477–483. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ichimi K, Kuchiwaki H, Inao S, Shibayama M, Yoshida J. Responses of cerebral blood flow regulation to activation of the primary somatosensory cortex during electrical stimulation of the forearm. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1997;70:291–292. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6837-0_90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.le Roux AA, Wallace MC. Outcome and cost of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2010;21:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matz PG, Sundaresan S, Sharp FR, Weinstein PR. Induction of HSP70 in rat brain following subarachnoid hemorrhage produced by endovascular perforation [see comments] J Neurosurg. 1996;85:138–145. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.1.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagley P, Higgins GC, Atkin JD, Beart PM. Multifaceted deaths orchestrated by mitochondria in neurones. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1802:167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S, Yamaguchi M, Zhou C, Calvert JW, Tang J, Zhang JH. Neurovascular protection reduces early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35:2412–2417. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141162.29864.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press Inc; San Diego, California: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prunell GF, Svendgaard NA, Alkass K, Mathiesen T. Delayed cell death related to acute cerebral blood flow changes following subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat brain. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:1046–1054. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.6.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarrafzadeh A, Haux D, Sakowitz O, Benndorf G, Herzog H, Kuechler I, Unterberg A. Acute focal neurological deficits in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: relation of clinical course, CT findings, and metabolite abnormalities monitored with bedside microdialysis. Stroke. 2003;34:1382–1388. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000074036.97859.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schubert GA, Poli S, Mendelowitsch A, Schilling L, Thome C. Hypothermia reduces early hypoperfusion and metabolic alterations during the acute phase of massive subarachnoid hemorrhage: a laser-Doppler-flowmetry and microdialysis study in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:539–548. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwerk C, Schulze-Osthoff K. Non-apoptotic functions of caspases in cellular proliferation and differentiation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1453–1458. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sehba FA, Mostafa G, Knopman J, Friedrich V, Jr, Bederson JB. Acute alterations in microvascular basal lamina after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:633–640. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.4.0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sehba FA, Mustafa G, Friedrich V, Bederson JB. Acute microvascular platelet aggregation after Subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:1094–1100. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.6.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sehba FA, Pluta RM, Zhang JH. Metamorphosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage research: from delayed vasospasm to early brain injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2011;43:27–40. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8155-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tyas L, Brophy VA, Pope A, Rivett AJ, Tavare JM. Rapid caspase-3 activation during apoptosis revealed using fluorescence-resonance energy transfer. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:266–270. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner DC, Riegelsberger UM, Michalk S, Hartig W, Kranz A, Boltze J. Cleaved caspase-3 expression after experimental stroke exhibits different phenotypes and is predominantly non-apoptotic. Brain Res. 2011;1381:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Shi XY, Yin J, Zuo G, Zhang J, Chen G. Role of Autophagy in Early Brain Injury after Experimental Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J Mol Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9575-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zubkov AY, Tibbs RE, Clower B, Ogihara K, Aoki K, Zhang JH. Morphological changes of cerebral arteries in a canine double hemorrhage model. Neurosci Lett. 2002;326:137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]