Abstract

Protein folding into tertiary structures is controlled by an interplay of attractive contact interactions and steric effects. We investigate the balance between these contributions using structure-based models using an all-atom representation of the structure combined with a coarse-grained contact potential. Tertiary contact interactions between atoms are collected into a single broad attractive well between the Cβ atoms between each residue pair in a native contact. Through the width of these contact potentials we control their tolerance for deviations from the ideal structure and the spatial range of attractive interactions. In the compact native state dominant packing constraints limit the effects of a coarse-grained contact potential. During folding however the broad attractive potentials allow an early collapse that starts before the native local structure is completely adopted. As a consequence the folding transition is broadened and the free energy barrier is decreased. Eventually two-state folding behavior is lost completely for systems with very broad attractive potentials. The stabilization of native-like residue interactions in non-perfect geometries early in the folding process frequently leads to structural traps. Global mirror images are a notable example. These traps are penalized by the details of the repulsive interactions only after further collapse. Successful folding to the native state requires simultaneous guidance from both attractive and repulsive interactions.

Keywords: energy landscape, principle of minimal frustration, structure-based model, all-atom representation, coarse grained contact map, cooperativity, misfolding, mirror image

Introduction

What are the relative roles of steric repulsion and attractive forces in protein folding?

Globular proteins, at the atomic level, are clearly dense objects. X-ray crystallographic images suggest there is very little free volume in protein interiors. Yet the rapid penetration of small molecule ligands such as O2 into proteins, at often very high rates, suggests that fluctuations making room for ligand transport are not too costly in free energy 1,2,3. Diffuse X-ray backgrounds4 and sophisticated multi-configuration fits to X-ray data5,6,7 also suggest there is at least a moderate level of structural disorder (~10%) at the side-chain level in the typical globular protein.

The importance of steric effects is evidenced by the observation that accommodating mutations with increased volume in evolved native protein structures is more difficult than accommodating mutations to smaller amino acid residues. Nevertheless protein interiors have been reconstructed with side chains very different from those constructed by evolution, with some success8,9,10,11,12. Another observation suggesting a limited role of detailed sterics in folding is that coarse grained simulations with unified residue potentials often predict protein structures reasonably well. We see that steric forces are important at the atomic level resolution but that their effects are buffered in some way by the flexibility of the folded protein structure. In this paper we explore the physics of the interplay between side chain degrees of freedom and the establishment of overall chain topology and how this interplay depends on the range of the inter-residue attractive forces.

One way of discussing this question is to use the language of macroscopic phase transitions. The final folded protein structure which is of rather low entropy can be regarded as a crystal. Should we think of the native states as nearly perfectly defined (with a few vacancies) or should we think of the native ensemble as a plastic crystal phase in which considerable side chain motion occurs? In laboratory studies near the folding midpoint, the process of folding often commences from a high entropy random coil ensemble of conformations with very sparse configurations. This ensemble is pretty clearly analogous to a gas. Many studies under more strongly nativizing conditions have revealed other dense phases of globular proteins which are only partially ordered. The term “molten globules” has long been associated with such phases, since Ptitsyn attracted attention to them and pointed out their importance.13

Many ways of characterizing both residual order and the disorder in molten globule phases have been developed. Many experiments show that some degree of native topology is already present in molten globules14,15,16,17,18 and other denatured states. One extreme view, in fact, is that the native topology is nearly perfect in the molten globule, like that seen in the X-ray structure but that side chains are mobile (like the plastic crystal phase idea for the folded ensemble mooted earlier). Another minimal view is that the molten globule is more disordered, a liquid crystalline assembly of secondary structure elements. This picture was first championed by Ptitsyn13 and later quantitatively analyzed by Ramirez, Luthey-Schulten and Wolynes19. The role of local secondary structure signals in further organizing the liquid crystalline globule giving rise to some native structure in the MG ensemble was highlighted by Saven and Wolynes20.

A liquid crystalline phase has ample opportunities for non-native contacts to form and thus has the dynamics typical of glass-forming liquids owing to escape from local free energy minima21,22,23. The latter, glassy, liquid crystalline view underpins many quantitative treatments of the folding free energy landscape of helical proteins24,20.

The plethora of possible partially ordered phases of globular protein matter opens up a large number of scenarios for protein folding under different thermodynamic conditions. A very common scenario (near the folding midpoint) is a more or less direct transition from the gas-like random coil state directly to a fully ordered (nearly fully) internal crystalline native structure. This process resembles inverse sublimation going directly from a gas-like phase to a crystalline solid-like phase. In the transition state ensemble, partially ordered phases may still play a role25,26.

In all-atom computer simulations even near TF often a significantly populated molten-globule like phase with a large amount of non-native structure usually is seen. The large amount of non-native structure strongly suggests that even the better computer simulations carried out today at an atomistic level are based on energy landscapes more rugged than the real one27, although we must acknowledge this conclusion certainly encounters controversy28.

In this paper we examine another aspect of the “sublimation” versus “condensation-freezing scenarios” which hinges on the nature of the inter-residue forces. We show that very short range attractions lead to the direct scenario while broader attractive wells lead to the liquid condensation-freezing/crystallization scenario. This dichotomy depending on the range of attractions resembles what is known about the phase transformations of simple substances where very short range interactions lead to sublimation without the possibility of a liquid phase.

While we regard the present study as largely conceptual, the lessons it holds may have practical consequences. While fully accurate protein structures can be used to predict folding kinetics quite well29, do lower resolution models like those obtained by homology modeling30,31,32 or ab initio structure prediction33,34,35 suffice for kinetic modeling? Here we show that if sufficient predictive accuracy is available short range attractive models can be used and direct transit to the folded state (like that usually found experimentally near TF) will occur in the simulation and mechanisms near the folding midpoint properly delineated. With lower precision models, where greater tolerances must be allowed, simulations may predict additional intermediates which actually are never populated.

Constructing Structure-Based Models with Variable Resolution

To quantify the interplay between side-chain steric effects and different ranges of attractive interactions between amino acids we investigate model systems that are derived from a structure-based model(SBM)36,25,37 with explicit representation of all heavy atoms38, which contains exclusively native-centered backbone potentials and tertiary contact interactions. For the tertiary contacts we have introduced a potential based on Gaussian functions39, much in the spirit of the sums of Gaussians in the associative memory hamiltonian40. The models presented here are variations of our standard all-atom SBM41,42,43, with the main difference that a single Cβ – Cβ interaction replaces several atom contacts while the excluded volume remains the same. Effectively the models combine a detailed representation of the atomic level structure with a coarse grained potential for tertiary contacts. The loss of structural information encoded in the attractive contact potential shifts the balance of control over the folding process towards the steric repulsive interactions.

We assume that attractive potentials and unspecific interactions will be relevant only for residue pairs with long sequence separations. Experience with predictive protein models shows that local structures can be determined with reasonable confidence from structural databases. Additional information may be necessary for pairs that are distant in sequence, because the available information becomes increasingly reduced and ambiguous with growing sequence distance. This information may come from different sources and may have limited structural resolution, leading to the introduction in the model of spatially broad attractive interactions. Limited spatial resolution is a trade off to limit energetic frustration, which is unavoidable because a predictive model will not be perfectly accurate.

Specifically we replace all the native attractive interactions between the atoms of any pair of residues p,q with a long sequence separation of Δp,q = |p−q| > 8 by a single interaction between their Cβ atoms. The width of the attractive well of the potential for this residue contact is varied for the different realizations of the model, allowing us to investigate how different levels of resolution lead to different outcomes. A sketch of this procedure is shown in Fig. 1. Atom contacts between residues with a short sequence separation of Δp,q = |p−q| ≤ 8 are retained as in the full all-atom structure-based model. Fragments of similar length are also frequently used in several structure prediction schemes34,44. Backbone interactions, which apply to covalently bound atoms, are also maintained unmodified from the all-atom structure-based model.

Fig. 1.

All-atom models with coarse-grained contact maps: Starting from a structure-based model with all-atom representation, atom contacts between pairs of residues with long sequence separations |p−q| > 8 are replaced by single residue contacts acting on the Cβ atoms. Pairs of residues with short sequence separations |p−q| ≤ 8 retain the individual atom contacts that are also present in the full structure-based all-atom model. Multiple atom contacts between a pair of residues can fully determine the relative position of their side chains. A given single contact between their Cβ atoms may be compatible with multiple configurations. Packing restrictions imposed by repulsive interactions between the side chain atoms gain in relevance.

Despite the coarse-graining of the contact interactions for residue pairs with long sequence separations, the models are still completely structure-based. All the minima of attractive contact potentials continue to be placed at the exact distances obtained from the crystal structure. Only the range (tolerance) of the geometrical deviations of tertiary contacts is increased. In the all-atom SBM multiple interactions between individual atoms of a residue pair forming a native contact can determine the distance and the relative orientations of their side chains. Within the coarse-grained contact interactions the single remaining potential between the Cβ atoms of a residue pair only depends on their separating distance. The relative orientation of the side chains is not controlled by the contact potential. Modifications to the width for the single potential between their Cβ atoms allow one further to control the tolerance for deviations in the contact distance adopted by the residues39.

While the tertiary interactions between residues with long sequence separations are thus coarse-grained, the structure is however still represented in atomic detail. Repulsive interactions between side chains and their packing constraints therefore remain fully effective in the models. To analyze also the effects of repulsive interactions we use variants of our models that additionally replace the term for the unspecific repulsion by Weeks-Chandler-Andersen(WCA) potentials45 with even shorter range.

In this way we can vary the range and the effectiveness of both the unspecific repulsive interactions and of the specific attraction between tertiary contact pairs to observe their respective influence on the formation of native protein structure.

All-atom structure-based model

The Hamiltonian for our structure-based model consists of bonded and non-bonded interactions.

| (1) |

Bonded interactions serve to determine the geometry of the protein chain and establish a local bias towards the native configuration. Non-bonded interactions provide excluded volume to the chain and provide additional stabilizing interactions between atoms that are separated in sequence but close in space in the native structure. All non-hydrogen atoms are individually represented in the model. The bonded interactions include harmonic potentials for bond lengths and bond angles. Further harmonic terms constrain peptide bonds and aromatic rings to planar geometries and maintain proper chirality.

| (2) |

Dihedral potentials V BB and V BB for backbone and side chain torsional angles use the same cosine potential

| (3) |

with different amplitudes εBB and εSC selected according to the scaling rules described in Ref. 38.

The non-bonded interaction between any pair of atoms i, j is selected by the corresponding element of the atom contact matrix CA, which is 1 if the atoms i, j are in contact in the native structure and 0 otherwise.

| (4) |

The determination is made according to the “shadow” algorithm, which generates possible contacts based on a distance cutoff, and then eliminates contacts as redundant if they are separated by interposed atoms.46 Contacts between atoms that belong to residues p,q with a sequence separation |p−q| ≤ 3 are also excluded.

Atom pairs that do not form native contacts interact by a purely repulsive potential

| (5) |

For simplicity a constant value of d is used for all the heavy atoms that are represented in the model. To create an alternative set of models with shorter range for the unspecific repulsion we replace V R by a WCA potential45. The WCA potential is derived from a Lennard-Jones potential that is shifted up to become zero at the location of its minimum. At shorter distances than the minimum distance the WCA potential is equal to this shifted Lennard-Jones potential, at longer distances it is set to zero.

| (6) |

Native contacts are stabilized by a potential V C with a minimum at the native distance and repulsive interaction at shorter distances. Typically modified Lennard-Jones potentials have been used for V C. For our purposes this choice is problematic because the shape of a Lennard-Jones potential is completely determined by the placement of the native minimum. We have recently introduced an alternative contact potential that offers more flexibility39:

| (7) |

| (8) |

It combines the repulsion V R with an attractive Gaussian function V G. The additional product term places the minimum of the total V C at the native distance at (ri, j,− Ai, j). In addition to the native distance the depth of the minimum, the width of the Gaussian, and also the atom diameter for the repulsive term remain as adjustable parameters, i.e. . All three values are relevant for the construction of models with coarse-grained contact maps.

Models with reduced native information

To support the introduction of a coarse-grained contact map at the residue level instead of contacts between individual atoms, the contact potential from Eq. (4) can be rewritten in terms of residues p,q and their constituent atoms A(p) and B(q) as

| (9) |

There is a unique correspondence between each atom A(p) and its index i used in Eq. (4).

From the atom contact map CA we can count the number of atom contacts between a pair of residues:

| (10) |

We use this count to define a residue contact map CR with elements

| (11) |

Contacts between residues with |p−q| ≤ 3 are not part of CA and remain excluded in CR. As residue contacts act on the Cβ atoms we further exclude contacts between glycine residues.

We now distinguish contacts between residues with short sequence separation |p−q| ≤ 8 from contacts between residues with long sequence separation |p−q| > 8and assign different contact potentials to them,

| (12) |

Short contacts retain the detailed contact interactions from the all-atom structure-based model,

| (13) |

Long contacts use the coarse-grained residue contact map, with interactions acting on the Cβ atoms,

| (14) |

The parameter di, j for the effective atom diameter in the repulsive part of the contact potential is kept identical in all cases to the value used in the purely repulsive potential for non-contacts. Especially for the residue contacts this possibility is crucial. With a Lennard-Jones contact potential between the Cβ atoms the interaction would soon become repulsive at distances below the native separation. This behavior is however only desirable in a fully coarse-grained model, when the amino acid structure is not directly represented in the model. The contact repulsion then reflects the approximate sizes of the whole side chains. Our models include the all-atom structure of the residues explicitly. This detailed treatment of side chain volume and packing would only be diluted by an averaged repulsive interaction. Contact amplitudes Ai, j are equal for all contacts in V short to the value εC that is determined according to the procedure from Ref. 38. In V long we set all Ai, j to a new constant value that is scaled by the numbers of replaced long atom contacts and of residue contacts to conserve the total contact energy in the native configuration, . Energetic information about the differing numbers of atom contacts between different residue pairs is thus dropped from the model together with the geometrical information contained in the atom contact distances.

The width of the Gaussian in V short is set proportional to the native distance, as it is done in the all-atom structure-based model to mimic the behavior of the conventional Lennard-Jones potentials: . In V long we use a constant width σi, j = σβ in the Gaussian term in the residue contacts in each model. Different values for σβ in different variants of the model represent varying degrees of assumed uncertainty in the structural input information. The values for σβ used in this study are 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 Å.

Results

We have investigated the impact of the described coarse-grained contact maps on the folding behavior of five small proteins with different folds and structural complexity, namely the helix bundles Protein A (PrA) and 434 Repressor (434rp), an SH3 domain, and the mixed alpha-beta proteins CI2 and FtsA. They range in size from 46 amino acids for PrA to 81 for FtsA. The full structure based models contain between 311 and 714 atom contacts. In the relatively simpler helix bundles, half of the contacts are formed between residues with sequence separations up to 8 residues and half between more distant pairs. In the three proteins that contain beta structures, the fraction of contacts between residue pairs with sequence separations larger than 8 residues is between 75% and 84%, with the highest value for FtsA. FtsA also has the most complex structure according to the mean sequence separation of residue contacts, 〈δ〉 = 32. The lowest complexities according to this measure are found again for the helix bundles, with 〈δ〉 =14 for PrA. This information is collected for all treated proteins in Table I.

Table I.

List of treated proteins

| Protein | PDB | N res | N A |

|

|

〈σ〉 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PrA | 1BDD | 46 | 311 | 153 | 158 | 14 | ||

| 434rp | 1R69 | 63 | 523 | 261 | 262 | 18 | ||

| SH3 | 1FMK | 57 | 481 | 79 | 402 | 23 | ||

| CI2 | 2CI2 | 64 | 481 | 118 | 363 | 22 | ||

| FtsA | 1E4F | 81 | 714 | 149 | 565 | 32 |

To describe the folding behavior of these proteins in our models, native-like atom contact distances are used as the main geometrical criterion for determining nativeness. The fraction of formed native contacts is a natural reaction coordinate for a structure-based energy model, because it also reflects the degree of energetic stabilization through the corresponding contact potentials. For the systems with coarse grained contact maps the geometrical criterion still describes native-like local structure. For contacts between residues pairs with short sequence separations, where the atom contact potential from the full structure-based model is retained, the direct correspondence to energetic stabilization also remains. The precise correspondence to energetic stabilization is lost for residue pairs with long sequence separations, whose atom contact potentials have been replaced by a single residue contact potential. The fraction of formed contacts in both groups is plotted separately as and in Fig. 2 A for the case of 434rp. In the full structure-based model, where both groups of contacts are treated in the same way, the behavior of the two groups is similar. Both are mostly unformed at higher temperatures, and the majority of contacts from both groups are formed cooperatively at the same transition temperature. The temperature dependence for the formation of the remaining contacts at lower temperatures is also identical for both groups. Only the fraction of contacts that is already randomly formed in the unfolded state above the transition temperature differs with sequence separation. As expected the fraction of formed contacts is higher for pairs separated by shorter loops.

Fig. 2.

Structure formation and stabilization: The transition between folded and unfolded states in all-atom models with coarse-grained contact maps is characterized through the temperature-dependent fraction Q of formed contacts. A: Fractions QAA of atom contacts for 434 repressor: Atom contacts between pairs of residues with sequence separation |p−q| ≤ 8 are directly included in all models. Their fraction in labeled and shown by black curves. Data for a model with the complete all-atom contact map are labeled AA. In the coarse-grained contact maps atom contacts between residue pairs with longer sequence separations |p−q| < 8 are replaced by single contacts between the Cβ atoms. The width parameter σβ of the attractive Gaussian contact well varies between models from 0.5 to 2.0 Å. The fraction of the replaced atom contacts that are geometrically formed is labeled and shown in red. In the coarse-grained models QAA is only a measure of structure, and not of direct energetic stabilization as it is in the full structure-based model where potentials for these contacts are included. Curves for the coarse-grained models are therefore dashed. Wider curves correspond to models with broader potentials for the Cβ contacts. B: Formation of the Cβ contacts used in coarse-grained contact maps, for 434 repressor: Black curves for from panel A are repeated for reference. Green curves give the fraction of formed Cβ contacts between residue pairs with sequence separations |p−q| > 8. Cβ contacts are defined as formed when the pair distance is within 2 σβ from the native value. The blue dashed curves use a stricter geometrical criterion: A native Cβ contact is considered to be formed when the distance between the Cβ atoms is within 1.0 Å of the native value.

In the models that employ coarse grained interactions for residue pairs that are distant in sequence, the transition temperatures for and still coincide in each system. The common transition temperature is higher for systems with broader potentials for the residue contacts between contact pairs with long sequence separations. For both and the fraction of atom contacts that is formed cooperatively at this transition temperature shrinks as the residue potentials used for contacts with long sequence separations are broadened. Below the transition temperature different temperature dependences of and arise from the different treatment of residue contact pairs that are close or distant in sequence. The group of atom contacts between pairs with short sequence separations, which are still stabilized by individual contact potentials, proceeds to completion with the same temperature dependence as in the full structure-based model. The fraction of formed atom contacts between residue pairs with long sequence distances, which are only stabilized indirectly via the coarse-grained contact potentials between the residues’ Cβ atoms, increases more slowly below the main transition temperature, so that the transition for these contacts becomes broadened. Further broadening of the transition occurs above the transition temperature for both groups of contacts. Broader potentials for the contacts between the Cβ atoms of residue pairs with long sequence separations move the onset of native-like structure formation to increasingly higher temperatures for both and .

The temperature dependent formation of the residue contacts defined between Cβ atoms of residue pairs with long sequence separations is plotted in Fig. 2B, again for 434rp. Their transition from low to high degrees of formation coincides with the transition monitored by the atom contacts in each system. Compared to the atom contacts, the transition for the residue contacts is more complete, when the distance cutoff for their formation is chosen to correspond to the actual width of the contact potential between the Cβ atoms in each system. When a stricter constant distance cutoff is chosen for the formation of the residue contacts, monitoring more precisely the adoption of closely native-like distances instead of the onset of energetic stabilization, the formation of residue contacts goes to completion more gradually below the transition temperature, in a manner more similar to the atom contacts.

Above the transition temperature an early onset of contact formation broadens the transition for the residue contacts to an even greater extent than for the atom contacts. The broadening effect is again strongest for those models using the widest attractive contact potentials, and it is most notable when the distance cutoff used to recognize contact formation matches the width of the potentials.

Fig. 3 summarizes the behavior of the atom contacts for the set of five investigated proteins. In models with coarse grained contact maps, all five proteins show the same broadening of the folding transition that is dominated by an early onset of structure formation above the cooperative folding temperature for both the groups of contacts with short and long sequence separations. All the proteins we studied also share the separation in behavior between these groups of contacts below the folding transition, where the complete formation of atom contacts with long sequence separations is delayed in models with coarse grained contact maps.

Fig. 3.

Broadening of folding transitions for different proteins: Characteristic temperatures Tv are used to summarize the behavior of and shown in panel A for the set of five tested proteins. is e.g. defined as the temperature where equals 0.25 (see markings in panel A). Temperatures for are plotted against the corresponding temperatures for to compare the relative progress of both groups of contacts. T0.25 and T0.75, marked by circles and diamonds respectively, are used to describe early and advanced contact formation. Data for models with complete atom contact maps are shown in the inset. Placement of the symbols for T0.25 close to the diagonal indicates that and reach the value 0.25 at similar temperatures. The same holds for T0.75. Folding progresses simultaneously for both groups of contacts. Small differences between T0.25 and T0.75 indicate that the transition occurs cooperatively over a narrow temperature range. Data in the main plot show the behavior of models with coarse-grained contact maps for contacts between residues with long sequence separations |p−q| > 8. The relative placement of data points for models with increasingly broader potentials for the residue contacts is indicated by the black arrows. Corresponding symbols showing T0.25 and T0.75 for each model of SH3 are in addition indicated by blue arrows. For the systems with coarse-grained contact maps only symbols for T0.25 are placed close to the diagonal, while those for T0.75 are displaced from it. Both and reach the value 0.25 at similar temperatures, but progress to 0.75 occurs at lower temperatures for . For both groups of contacts separately the difference between T0.25 and T0.75 is increased compared to that for the complete all-atom structure-based models. The broad and gradual character of the transition indicated by this difference grows for each tested protein with increasing width of the contact potential for the Cβ contacts in the coarse-grained contact map.

The relationship between formation of native-like local structure and collapse is exhibited in Fig. 4 for 434rp. Structure formation is here quantified by the fraction of all native-like atom contacts QAA, without the distinction by sequence separation made above. The behavior of contact formation is compared to the temperature dependence of the radius of gyration as a measure of compactness. Protein folding is monitored by Rg as a transition from high values for extended unfolded conformations at high temperatures to a low value for the compact folded structure. For the full structure-based model this transition temperature coincides with the transition temperature for forming native contacts, and both transitions are equally sharp. For models with coarse grained contact maps, the transition in Rg becomes more gradual as the width of the contact potential is increased for residue contacts between pairs with long sequence separations. The transition is also somewhat shifted, so that native-like values of Rg are reached at higher temperatures in these models, but the onset of collapse occurs at even higher temperatures. Both effects together lead to a growing separation between contact formation and collapse. The same qualitative behavior is also seen in models with WCA potentials for the unspecific repulsive interactions between atoms. With its shorter range, the WCA potential leads to even earlier collapse, while the temperature dependence of contact formation doesn’t change.

Fig. 4.

Collapse: The transition between extended and compact states in all-atom structure-based models of 434 repressor with coarse-grained contact maps is characterized through the temperature dependence of the radius of gyration, shown in red. Black curves give the fraction QAA of formed atom contacts for reference. Data for a model with the complete all-atom contact map is labeled AA. In the coarse-grained contact maps atom contacts between residue pairs with sequence separations |p−q| > 8 are replaced by single contacts between their Cβ atoms. The width parameter σβ of the attractive Gaussian contact well varies between models from 0.5 to 2.0 Å. Open circles add data for models where additionally a WCA potential is substituted for the 12th power term for the unspecific repulsive interaction between atom pairs that form no native contact.

Fig. 5 summarizes the relationship between collapse and structure formation for all five investigated proteins. The described behavior is confirmed in all cases. When the width of the attractive potentials is increased in these models, the separation in temperature between collapse and formation of native-like atom contacts increases. While the strength of the effect differs between proteins for identical models, the different models for each protein all follow a similar trend. With the coarse grained contact maps, collapse is increasingly further advanced before local structure formation even begins.

Fig. 5.

Separation of the collapse and structure formation for different proteins: Characteristic Temperatures T0.25 are used to summarize the relationship between Rg and QAA, shown in Fig. 4, for all tested proteins. T0.25 (QAA) is the temperature, where QAA equals 0.25. Similarly the normalized radius of gyration equals 0.25 at T0.25 (Rg). Solid symbols compare T0.25 (Rg) and T0.25 (QAA) for models with complete atom contact maps. Their placement close to the diagonal indicates that compaction and formation of native structure happen together. Open symbols correspond to models with coarse-grained contact maps for residue pairs with long sequence separations |p−q| > 8. A single contact between their Cβ atoms replaces all atom contacts between such pairs. The width parameter σβ of the attractive Gaussian contact well increases between models from 0.5 to 2.0 Å. For each protein separately T0.25 (Rg) is increasingly higher than T0.25 (QAA) for models with broader potentials for the Cβ contacts. Formation of native atom contacts proceeds only after collapse is already advanced.

Free energy profiles as functions of Q and Rg display a qualitative change in behavior underlying this trend. As shown for 434Rp in Fig. 6A, the profiles for the full structure-based model at the folding temperature shows two coexisting minima corresponding to the folded and unfolded states. In simple two state folders like 434Rp they are connected by a single barrier, which here measures about 5 kBT. The folded state is restricted to a narrow range of values around the native Rg, but it covers a larger range of high values in Q. The unfolded state is located at low Q and consists of a basin that extends towards larger radii Rg. Upon the change to coarse-grained contact maps with increasingly wide residue contacts between the Cβ atoms of residue pairs with sequence separations Δp,q > 8 both minima shift towards the barrier in the profile, and the height of the barrier is reduced. For 434Rp the barrier has shrunk to about 1 kBT for the model using σβ=1.0 Å for the width of the residue contacts. With still wider contacts the barrier eventually vanishes completely. Folded and unfolded states merge into a single basin that shifts along the landscape with decreasing temperature from extended unfolded states to compact native-like configurations. Compact states with low Q are adopted in between, and two destabilized branches of the basin extend towards folded and unfolded regions. For 434Rp this single state “downhill” behavior is first encountered in the model with σβ =2.0 Å. For FtsA, where the fraction of contacts with sequence separations Δp,q > 8 is higher, single-state behavior is already reached at σβ =1.0 Å. For both proteins the remaining barrier in any given model is lowered further when WCA repulsion is introduced.

Fig. 6.

Loss of two-state behavior, in two dimensional free energy-landscapes as functions on Rg and QAA. A: The structure-based model of 434 repressor using the complete atom contact map shows folded and unfolded basins in equilibrium separated by a barrier of 5 – 6 kBT. In the inset, the corresponding landscape is shown for a model with a coarse grained contact map that replaces atom contacts between residue pairs with long sequence separations |p−q| > 8 by a single contact between their Cβ atoms. The width parameter for the contact potential is σβ = 2.0 Å. Here the barrier between the folded and unfolded basins is reduced to 1 – 2 kBT. B: For FtsA two state-behavior is already replaced by a shifting single basin in the model using residue contacts with σβ = 1.0 Å between Cβ atoms. The main plot shows the situation at T=1.625, between the folded and unfolded parameter regions. The alternative landscapes for T = 1.2 and T = 2.0, given as insets, show the folded and unfolded regimes.

The loss of two-state folding behavior in our systems with unspecific interactions poses practical challenges for the application of such models. A clear transition from unfolded to native-like configurations can no longer be observed at constant temperature. For our systems folding trials were performed instead with a minimal annealing routine using linear temperature ramps. In order to emphasize possible kinetic traps a fast cooling rate has been chosen. It was adjusted to produce a small fraction of misfolded outcomes also for the simple helix bundles in the full structure-based models with all-atom contact maps. Results from 50 folding attempts for each protein indicate that using the coarse-grained contact maps also increases the likelihood for certain scenarios of misfolding. Especially with those potentials having the broadest attractive contacts, global mirror images of the native structure arise as an extreme outcome. These structures are approximate mirror images at the coarse grained level that describes the relative positions of elements of secondary structure and their connecting loops. Local constraints with chemical motivation, like the planarity of peptide bonds or of aromatic rings, which are enforced by the harmonic potentials of improper dihedral interactions, remain satisfied. Other local structures like individual helices may also be formed with the correct native-like orientation, or they may be disrupted to comply with the inverted global geometry. Such distortions are only opposed by the softer proper dihedrals. While part of the local structure is thus disrupted, such mirror images apparently satisfy nearly all constraints encoded in the broad contact potentials that form the coarse-grained contact maps of these models.

These unspecific residue contacts are able to lock in mirror images and other misfolded chain geometries through their high stabilization and their observed tendency to form early during the folding process, in spite of high energetic penalties for the completed structure from other parts of the potential.

Repulsive interactions contribute significantly to the energetic penalties that are realized in such final misfolded structures. Mostly this contribution is however indirect, apparently the excluded volume interactions distort other degrees of freedom with less steep potentials, like dihedral angles. Repulsive interactions can also not prevent the falling into such traps because of their short range, especially compared to the unspecific residue contacts that form during the early collapse.

Early collapse alone has long been identified as a cause of slow folding, since trapping is increased in compact structures.47 Broadened contact potentials would be likely to strengthen this effect through their capacity to stabilize competing non-native topologies. This effect of the broadened contact potentials would apply to proteins that fold natively through compact intermediates with reduced native structure even without any nonspecific tendencies to induce early collapse as well.

Some of the misfolded results encountered in our folding trials could probably have been avoided by a more elaborate annealing procedure. But with the minimal annealing scheme used here to emphasize misfolding behavior, broad potentials also show some advantages. As the pie charts in Fig. 7b indicate, the fraction of native outcomes, shown in green, is highest for 434Rp with the full all-atom structure-based model. A success rate of 90% suggests that the annealing is only slightly faster than optimal. Coarse grained contact maps with increasing width of the attractive potentials decrease the number of correctly folded results found. For the structurally most complex test protein FtsA, the same annealing schedule produced only 20% native outcomes with the full structure-based all-atom model. With narrow residue potentials between the Cβ atoms of residue pairs with long sequence separations only few native-like results remain. But by using the large value of σβ =2.0 Å for the width parameter of these residue contacts, 20% native outcomes are recovered. Similar behavior is observed for SH3, where Cβ contacts with σβ = 2.0 Å again produce a higher fraction of native-like outcomes than the same coarse-grained contact map with more narrow contacts. The unspecific long contacts here confer some tolerance against kinetic traps as well as possibilities for misfolding.

Fig. 7.

Refolding outcomes: Global mirror images, shown for FtsA, arise as a telling misfolding scenario in models that use broad contact potentials between Cβ atoms in coarse-grained contact maps for residue pairs with long sequence separations |p−q| > 8. A simple annealing schedule was adopted to compensate the loss of folding ability at constant T in these models. The pie charts give the number of native outcomes, of structures closer to the mirror image, of clear mirror images, and of other misfolded structures in a set of 50 folding attempts for each tested protein.

When native-like topologies are reached during the annealing procedure, the final structures that are adopted by these models at low temperature turn out to be very close to the crystal structure that is encoded in the potentials. For the native-like outcomes counted in Fig. 7 the root mean square deviation of the backbone to the native configuration is generally smaller than 0.5 Å. Within these limits the deviations are larger in models with coarse-grained contact maps, where single contact potentials between Cβ atoms are used for residue pairs with sequence separations Δp,q > 8. Among these models the deviations furthermore increase with growing width of the potentials used for the Cβ contacts that constitute the coarse-grained part of the contact maps. But the loss of precision is limited. Notably the deviations do not grow in proportion with the width of individual residue contact potentials. For practical purposes when native-like topologies are produced the low temperature minima of all tested models can be considered as identical to the crystal structure. The broad attractive interactions do not impede the realization of the encoded precise native bias.

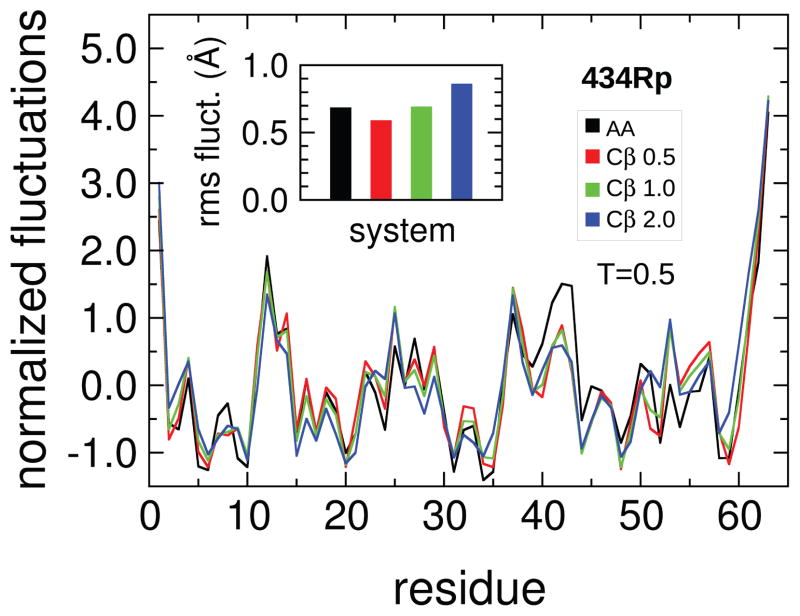

To further assess how well the native state is represented in these models we consider the root mean square fluctuations around the native configuration as a practically relevant property. It is presented in Fig. 8 for 434Rp. Fluctuation profiles are shifted to zero mean and normalized to a variance of one for easier comparison of their shapes. The data for the full structure-based model are given by the black trace. Results for the models coarse grained contact maps are shown in red, green and blue for values of σβ = 0.5,1.0,2.0 Å respectively.

Fig. 8.

Native dynamics: RMS fluctuations around the native configuration for 434 repressor. Fluctuations of the Cβ atoms at T = 0.5 are shown. Data are shifted and normalized to have zero mean and unit variance for comparison between systems. Actual RMS fluctuation amplitudes are given in the inset. The behavior of a model with the complete atom contact map is shown in black. Results for models with coarse-grained contact maps, using single contacts between the Cβ atoms of residue pairs with long sequence separations |p−q| > 8, are given by the colored lines. The width parameter σβ of the attractive Gaussian contact well for the residue contacts varies between models from 0.5 to 2.0 Å.

The unscaled amplitudes are shown in the inset as root mean square averages over all residues. Here the influence of the width chosen for the Cβ contacts is apparent. Narrow contacts, with σβ = 0.5 Å, lead to a reduced level of fluctuations. Amplitudes grow with increasing width of the contact potential. The level for σβ =1.0 Å is very similar to that in the full structure-based model, and fluctuations are clearly larger in the model with σβ =2.0 Å.

Meanwhile the general features of the fluctuation profile are preserved in the models with coarse grained contact maps, as for example the high peak at residue 12, the double peak around residue 40, and other features down to small maxima like the peaks around residues 8 or 32. Quantitative differences occur, most notably in the double peak around residue 40, where one of the two peaks is strongly reduced in all the models with coarse-grained contact maps. There is however no strong dependence of these quantitative changes upon the width of the residue potentials. Most of the effect seems related to the introduction of residue level contacts themselves, and not to their broadening.

Conclusions

The interplay between steric interactions and attractive contact potentials is clearly governed by the different reach of both types of interactions. Increasing the width of the attractive potential wells gives an extended range to contact interactions. This broadening of the attractive wells results in less cooperative transitions since residues start to feel each other even in the more extended structures. In its early stages the collapse, which is driven by the formation of these residue contacts, proceeds without the perfect formation of native-like local structure. Since detailed attractive interactions have been replaced by an average residue-residue interaction, less precise structures are formed. Native-like local configurations, signaled by a high fraction of native atom contact distances, only appear at the later stages of folding. The short-range attractive interactions for contacts close in chain and the repulsive interactions only influence the process once the structure is sufficiently compact.

We can conclude from the partially misfolded outcomes observed with the coarse-grained contact maps that steric effects and local contacts play significant cooperating roles in guiding the folding process in the fully detailed model. The coarse grained contacts with very broad attractive potentials are able to lock the system into partially folded global structures since they are formed at early stages of the folding process when conflicting interactions are not yet effective. Energetic penalties are imposed only at later stages of folding by steric repulsion and unsatisfied short-range attractive contacts. Under the annealing conditions chosen in this study, these penalties can not correct some folding mistakes that have already been stabilized by the broad residue contacts. But narrower long-range contacts produce less of these misfolded outcomes although on their own they would be equally suited geometrically to stabilize them. Observations with the WCA potential confirm the relevance of the relative ranges of repulsive and attractive interactions. It is interesting to notice that the repulsive WCA potential strengthens both the broadening of the collapse transition and the loss of cooperativity during folding.

Attractive contact potentials and of repulsive steric interactions both act simultaneously to control protein folding in realistic models. By modulating the range of these long-range attractive interactions we were able to identify the different roles of these two contributions. Attractive interactions provide the driving force for collapse, while steric effects exclude many unproductive folding routes. A detailed representation of the protein structure can improve the precision in the attractive contact potentials in a protein model. Naturally packing constraints are most effective in dense configurations. The compact native state is thus most tolerant against imprecise contact potentials. In extended states earlier during the folding process, the early stabilization of incorrect structures can limit access to the correct native one and therefore limit the corrective effect of steric penalties.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics (NSF PHY-0822283) and also by NSF Grant MCB-1051438 and by Grant R01 GM44557 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Lakowicz JR, Weber G. Quenching of Protein Fluorescence by Oxygen. Detection of Structural Fluctuations in Proteins on the Nanosecond Time Scale. Biochemistry. 1973;12(21):4171–4179. doi: 10.1021/bi00745a021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinbach PJ, Ansari A, Berendzen J, Braunstein D, Chu K, Cowen BR, Ehrenstein D, Frauenfelder H, Johnson JB, Lamb DC, Luck S, Mourant JR, Nienhaus GU, Ormos P, Philipp R, Xie A, Young RD. Ligand Binding to Heme Proteins: Connection between Dynamics and Function. Biochemistry. 1991;30(16):3988–4001. doi: 10.1021/bi00230a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strambini GB, Gonnelli M. Amplitude Spectrum of Structural Fluctuations in Proteins from the Internal Diffusion of Solutes of Increasing Molecular Size: A Trp Phosphorescence Quenching Study. Biochemistry. 2011;50(6):970–980. doi: 10.1021/bi101738w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarage JB, Clarage MS, Phillips WC, Sweet RM, Caspar DLD. Correlations of atomic movements in lysozyme crystals. Proteins: Struc Func Bioinf. 1992;12(2):145–157. doi: 10.1002/prot.340120208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacArthur MW, Thornton JM. Protein side-chain conformation: a systematic variation of chi one mean values with resolution - a consequence of multiple rotameric states? Acta Cryst D. 1999;55 (5):994–1004. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapovalov MV, Dunbrack RL. Statistical and conformational analysis of the electron density of protein side chains. Proteins: Struc Func Bioinf. 2007;66:279–303. doi: 10.1002/prot.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang PT, Ng HL, Fraser JS, Corn JE, Echols N, Sales M, Holton JM, Alber T. Automated electron-density sampling reveals widespread conformational polymorphism in proteins. Protein Sci. 2010;19:1420–1431. doi: 10.1002/pro.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gassner NC, Baase WA, Matthews BW. A test of the “jigsaw puzzle” model for protein folding by multiple methionine substitutions within the core of T4 lysozyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93 (22):12155–12158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mollah AKMM, Aleman MA, Albright RA, Mossing MC. Core Packing Defects in an Engineered Cro Monomer Corrected by Combinatorial Mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1996;35(3):743–748. doi: 10.1021/bi951959f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahiyat BI, Mayo SL. Probing the role of packing specificity in protein design. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10172–10177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazar GA, Desjarlais JR, Handel TM. De novo design of the hydrophobic core of ubiquitin. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1167–1178. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mooers BHM, Datta D, Baase WA, Zollars ES, Mayo SL, Matthews BW. Repacking the Core of T4 Lysozyme by Automated Design. J Mol Biol. 2003;332(3):741–756. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00856-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolgikh DA, Gilmanshin RI, Brazhnikov EV, Bychkova VE, Semisotnov GV, Venyaminov SY, Ptitsyn OB. α-lactalbumin: compact state with fluctuating tertiary structure? FEBS Lett. 1981;136(2):311–315. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baum J, Dobson CM, Evans PA, Hanley C. Characterization of partly folded protein by NMR methods – studies on the molten globule state of guinea-pig alpha-lactalbumin. Biochemistry. 1989;28 (1):7–13. doi: 10.1021/bi00427a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jennings PA, Wright PE. Formation of a molten globule intermediate early in the kinetic folding pathway of apomyoglobin. Science. 1993;262:892–896. doi: 10.1126/science.8235610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onuchic JN. Contacting the protein folding funnel with NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94 (14):7129–7131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raschke TM, Marqusee S. The kinetic folding intermediate of ribonuclease H resembles the acid molten globule and partially unfolded molecules detected under native conditions. Nature Stru Biol. 1997;4(4):298–304. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu LC, Kim PS. A specific hydrophobic core in the α-lactalbumin molten globule. J Mol Biol. 1998;280(1):175–182. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luthey-Schulten Z, Ramirez BE, Wolynes PG. Helic-coil, liquid crystal, and spin-glass transitions of a collapsed heteropolymer. J Phys Chem. 1995;99(7):2177–2185. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saven JG, Wolynes PG. Local Conformational Signals and the Statistical Thermodynamics of Collapsed Helical Proteins. J Mol Biol. 1996;257(1):199–216. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryngelson JD, Wolynes PG. Spin Glasses and the statistical mechanics of protein folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7524–7528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryngelson JD, Wolynes PG. Intermediates and barrier crossing in a random energy model (with applications to protein folding) J Phys Chem. 1989;93(19):6902–6915. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG, Luthey-Schulten Z, Socci ND. Toward an outline of the topography of a realistic protein-folding funnel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3626–3630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leopold PE, Montal M, Onuchic JN. Protein folding funnels – a kinetic approach to the sequence structure relationship. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(18):8721–8725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryngelson JD, Onuchic JN, Socci ND, Wolynes PG. Funnels, Pathways, and the Energy Landscape of Protein Folding: A Synthesis. Proteins Stru Func Bioinf. 1995;21:167–195. doi: 10.1002/prot.340210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolynes PG. Folding funnels and energy landscapes of larger proteins within the capillarity approximation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(12):6170–6175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia AE, Onuchic JN. Folding a protein in a computer: An atomic description of the folding/unfolding of protein A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(24):13898–13903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335541100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowman GR, Pande VS. Protein folded states are kinetic hubs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(24):10890–10895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003962107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chavez LL, Onuchic JN, Clementi C. Quantifying the roughness on the free energy landscape: Entropic bottlenecks and protein folding rates. J Amer Chem Soc. 2004;126:8426–8432. doi: 10.1021/ja049510+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bino J, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling by iterative alignment, model building and model assessment. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31(4):3982–3992. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Skolnick J. The protein structure prediction problem could be solved using the current PDB library. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(4):1029–1034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407152101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Misura KMS, Chivian D, Rohl CA, Kim DE, Baker D. Physically realistic homology models built with rosetta can be more accurate than their templates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(14):5361–5366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509355103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardin C, Eastwood MP, Prentiss MC, Luthey-Schulten Z, Wolynes PG. Associative memory Hamiltonians for structure prediction without homology: Alpha/Beta proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1679–1684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252753899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hegler JA, Lätzer J, Shehu A, Clementi C, Wolynes PG. Restriction versus guidance in protein structure prediction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(36):15302–15307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907002106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helles G. A comparative study of the reported performance of ab initio protein structure prediction algorithms. J R Soc Interface. 2008;5:387–396. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2007.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ueda Y, Taketomi H, Go N. Studies on protein folding, unfolding, and fluctuations by computer simulation. ii a three-dimensional lattice model of lysozyme. Biopolymers. 1978;17:1531–1548. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitford PC, Noel JK, Gosavi S, Schug A, Sanbonmatsu KY, Onuchic JN. An All-Atom Structure-Based Potential for Proteins: Bridging Minimal Models with Empirical Forcefields. Proteins: Stru Func Bioinf. 2009;75:430–441. doi: 10.1002/prot.22253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lammert H, Schug A, Onuchic JN. Robustness and generalization of structure-based models for protein folding and function. Proteins: Stru Func Bioinf. 2009;77:881–891. doi: 10.1002/prot.22511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedrichs MS, Wolynes PG. Toward Protein Tertiary Structure Recognition by Means of Associative Memory Hamiltonians. Science. 1989;246:371–373. doi: 10.1126/science.246.4928.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noel JK, Sulkowska JI, Onuchic JN. Slipknotting upon native-like loop formation in a trefoil knot protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(35):15403–15408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009522107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jamros MA, Oliveira LC, Whitford PC, Onuchic JN, Adams JA, Blumenthal DK, Jennings PA. Proteins at Work A combined small-angle X-ray scattering and theoretical determination of the multiple structures involved in the protein kinase functional landscape. J Bio Chem. 2010;285(46):36121–36128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nechushtai R, Lammert H, Michaeli D, et al. Allostery in the ferredoxin protein motif does not involve a conformational switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(6):2240–2245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019502108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bujnicki JM. Protein-Structure Prediction by Recombination of Fragments. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:19–27. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weeks JD, Chandler D, Andersen HC. Role of Repulsive Forces in Determining the Equilibrium Structure of Simple Liquids. J Chem Phys. 1971;54(12):5237–5247. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noel JK, Whitford PC, Sanbonmatsu KY, Onuchic JN. SMOG@ctbp: simplified deployment of structure-based models in GROMACS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo Z, Thirumalai D. Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Folding of a de Novo Designed Four-helix Bundle Protein. J Mol Biol. 1996;263(2):323–343. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]