Abstract

Gene delivery vectors based on recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) are powerful tools for studying myogenesis in normal and diseased conditions. Strategies have been developed to use AAV to increase, down-regulate, or modify expression of a particular muscle gene in a specific muscle, muscle group(s), or all muscles in the body. AAV-based muscle gene therapy has been shown to cure several inherited muscle diseases in animal models. Early clinical trials have also yielded promising results. In general, AAV vectors lead to robust, long-term in vivo transduction in rodents, dogs, and non-human primates. To meet specific research needs, investigators have developed numerous AAV variants by engineering viral capsid and/or genome. Here we outline a generic AAV production and purification protocol. Techniques described here are applicable to any AAV variant.

Keywords: AAV, Adeno-associated virus, Muscle, Gene therapy, Gene transfer/delivery, Serotype, Muscular dystrophy, Dystrophin, Alkaline phosphatase

1. Introduction

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a single-stranded DNA virus discovered in 1965 (1). It belongs to the Dependovirus genus of the Parvoviridae family. The 4.7 kb wild type AAV genome encodes two major open reading frames. The rep gene expresses viral replication proteins and the cap gene expresses viral capsid proteins. At the ends of the AAV genome are the inverted terminal repeats (ITRs). The ITR forms a T-shaped hairpin structure. It is essential for AAV replication and packaging. The mature virion is a ~20 nm nonenveloped icosahedral particle containing either a plus- or minus-strand genome. Although mature AAV virion is infectious in mammalian cells, the replicative AAV life cycle requires helper function from adenovirus or herpesvirus (2). In the absence of helper virus coinfection, AAV genome is either integrated in the host genome or maintained as double stranded circular episomes (3–5).

Recombinant AAV vector is generated by replacing the wild type AAV open reading frames with a target (therapeutic or marker) gene expression cassette. Since initial cloning of the AAV genome into a plasmid format in early 1980s (6, 7), tremendous progress has been made in developing AAV into a versatile and effective gene delivery vehicle (8). Recent clinical success in AAV gene therapy for inherited diseases further raises the enthusiasm of applying AAV technology in translational medicine (9–12).

AAV vector is one of the most attractive gene transfer tools in studying basic muscle biology and in developing novel genetic therapies for muscle diseases. Direct local muscle injection and systemic (intravascular or intraperitoneal) AAV administration have been used to achieve single muscle, muscle group, and even whole body muscle transduction. These preclinical studies have revealed robust and persistent (in months and years) transgene expression in normal and diseased muscles in various animal models including non-human primates. Besides gene addition/replacement/over-expression, AAV has also been used to down-regulate gene expression (e.g., via RNA interference) or to modulate RNA processing (e.g., via exon skipping). In many cases, AAV-mediated muscle gene transfer has helped investigators to obtain critical information that may otherwise take years to get if a conventional approach is used (such as transgenic modeling in mice).

Most of the earlier AAV gene transfer studies used AAV serotype-2 (AAV-2). To further improve the efficiency and specificity of AAV-mediated gene transfer, investigators have developed numerous AAV variants by viral genome engineering and/or capsid modification. The single-stranded nature of the AAV genome impedes immediate transcription. To circumvent this problem, self-complementary AAV (scAAV) vectors are developed by removing the terminal resolution site in one of the ITRs (13). By deleting the d-sequence in one of the ITRs, single polarity AAV vector can also be generated containing either the plus or the minus strand only (14, 15). A major limitation of AAV vector is its small packaging capacity. A series of dual vector strategies including cis-activation, trans-splicing, overlapping, and hybrid are now available to effectively overcome this constraint (16).

Several rate-limiting steps of AAV transduction (such as the uptake, intracellular processing, and uncoating) are determined by the capsid. Besides naturally occurring AAV serotypes, many creative strategies have been explored to generate novel viral particles with distinctive phenotypes. These include proviral sequence rescue from mammalian tissues, rational design based on known AAV structure/biology (such as peptide ligand insertion, mosaic capsid reconstitution, and tyrosine mutation), and direct evolution by error-prone PCR/DNA shuffling (reviewed in refs. (17–20)). Collectively, these newly engineered AAV vectors offer a broad range of selection to meet different experimental needs.

With the expansion of our knowledge on AAV transduction biology and AAV vector engineering, methods for AAV production and purification have also gone through revolutionary changes (reviewed in refs. (21–27)). The original method requires three components including a cis plasmid carrying an ITR-flanked target gene expression cassette, a trans plasmid supplying AAV replication and structural proteins, and a wild type adenovirus as the helper. A complicated procedure involving plasmid cotransfection and adenovirus coinfection is carried out to generate crude AAV lysate. AAV vector is then extracted from the crude lysate through one round of cesium chloride (CsCl) gradient banding. Besides being cumbersome and low yield, high level adenovirus carryover often skews experimental results. The newly developed transient plasmid cotransfection method has essentially solved the issue of adenovirus contamination. To meet the need of large animal study and clinical trial, new platforms have also been developed using producer cell lines, baculovirus system, and column chromatography purification for large-scale production.

In this protocol, we outline a procedure based on transient plasmid cotransfection and CsCl isopycnic ultracentrifugation. This method can be used to generate high quality vector stock of any AAV variant.

2. Materials

2.1. Recombinant AAV Vector Production

293 Cells (American Type Culture Collection). This is an adenovirus transformed human fetal kidney cell line (28). A 4.3 kb adenoviral DNA (nucleotide 1–4,344) is inserted in chromosome 19 in these cells. They constitutively express adenoviral E1a and E1b gene (29) (see Note 1; Fig. 1).

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing high glucose and l-glutamine. Store at 4°C.

Fetal bovine serum (FBS). Store at −20°C.

100× Penicillin G (10,000 Unit/mL) – Streptomycin (10 mg/ mL). Store at −20°C.

Adenoviral helper plasmid (pHelper) (Stratagene) (see Notes 2 and 3).

The cis plasmid carrying the vector genome (ITR-promoter-target gene-pA-ITR) (see Note 2).

2.5 M CaCl2. Sterilize by filtration and store at −20°C.

2× HBS buffer: 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM Na2HPO4, and 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.05 ± 0.05. Sterilize by filtration and store at −20°C (see Note 5).

150 mL Corning Pyrex fleaker.

Cell lifter (Corning).

150 mm Cell culture plates.

IEC Centra CL3R refrigerated table top centrifuge.

5, 10, and 25 mL Sterile Costar Stripette disposable pipettes.

250 mL Sterile polypropylene centrifuge bottle.

10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0).

15 mL Sterile polypropylene centrifuge tube.

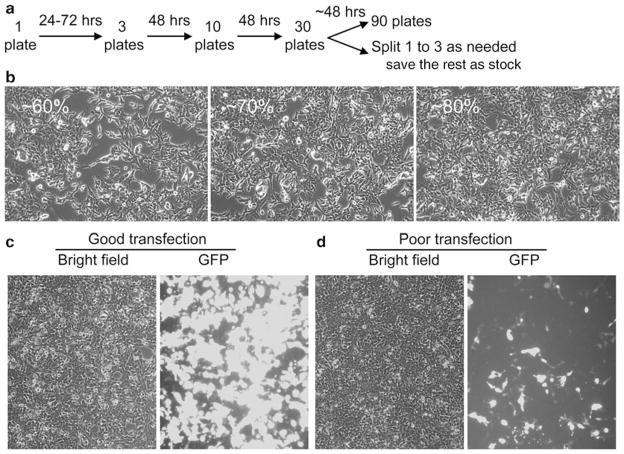

Fig. 1.

293 Cell propagation and transfection. (a) Schematic outline of 293 cell propagation. A freshly thawed stock vial may take up to 3 days to reach confluency. Split it 1:3. Forty-eight hours later, split again to 10 × 150 mm plates. After another 48 h, split to 30 × 150 mm plates. At this stage you may split 1:3 for the number of plates needed for your adeno-associated virus (AAV) preparation and freeze the remaining as stock. If you are doing a large preparation, you may split all 30 plates to 90 plates. Cells are usually ready for transfection at ~48 h after the last split. (b) Representative photomicrographs showing 293 cells at ~60% (left ), 70% (middle) and 80% (right ) confluency. Transfection at 70% confluency gives the highest AAV yield. (c, d) Representative photomicrographs showing transfection efficiency at 50 h after calcium phosphate transfection. (c) Shows a good transfection and (d) shows a poor transfection. In case of poor transfection, one should stop AAV preparation and re-start. The viral yield is usually several log folds lower from poorly transfected cells.

2.2. Recombinant AAV Purification

Dry ice/ethanol bath.

37°C Water bath.

15 and 50 mL Sterile polypropylene centrifuge tubes.

Misonic Sonicator S3000.

DNase I (11 mg protein/vial, total 33 K [kunitz] units) (see Note 6).

10% Sodium deoxycholate. Store at room temperature.

0.25% Trypsin-EDTA. Store at 4°C.

Optical grade CsCl.

Eppendorf 5810R bench-top refrigerated centrifuge.

Beckman-Coulter Optima XL-80 ultracentrifuge (see Note 7).

Beckman swinging bucket 55 titanium (SW55 Ti) rotor (see Note 7).

1 in. 20G Needle.

1.5 in. 25G Needle.

5.1 mL (13 × 51 mm) Beckman polyallomer ultracentrifuge tube (see Note 8).

10,000 Molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) Slide-A-Lyze dialysis cassette (Pierce) (see Note 9).

AAV Dialysis buffer: 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Autoclave. Cool to 4°C before use.

2.3. Titer Determination and Quality Control

AAV slot blot digestion buffer: 400 mM NaOH, 20 mM EDTA. Freshly made before use.

Slot blot hybridization solution: 5× SSC, 5× Denhardts’s solution, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 50% formamide, add 100 μg/mL denatured salmon sperm DNA just before use.

Bio-Dot SF manifold microfiltration apparatus (Bio-Rad).

Hybond-N plus membrane (GE Healthcare).

Techne HB-1D roller bottle hybridization oven.

AAV PCR alkaline digestion buffer: 25 mM NaOH, 0.2 mM EDTA.

AAV PCR neutralization buffer: 40 mM Tris–HCl, pH 5.0.

Primers for quantitative PCR determination of AAV titer (see Table 1).

ABI 7900HT fast real-time PCR system.

Fast SYBR green PCR master mixture.

MicroAmp optical 96-well reaction plate.

MicroAmp optical adhesive film.

AAV copy number controls (see Note 10).

JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope.

Holey carbon coated copper 200 mesh grid (Polysciences).

98% Uranyl acetate (see Note 11).

EndoSafe Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) gel clot test kit (Charles Rivers Laboratory).

Table 1.

Primers for quantitative PCR

| Target region | Primer sequence | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| RSV promoter | Forward (DL553): GGTTGTACGCGGTTAGGAGT Reverse (DL554): GGCATGTTGCTAACTCATCG |

127 |

| CMV/CAG enhancer | Forward (DL560): TTACGGTAAACTGCCCACTTG Reverse (DL561): CATAAGGTCATGTACTGGGCATAA |

119 |

| Human DMD ex 69/70 | Forward (DL1294): TTTTCTGGTCGAGTTGCAAAAG Reverse (DL1295): CCATGTTGTCCCCCTCTAAGAC |

196 |

3. Methods

3.1. Recombinant AAV Vector Production

Propagate 293 cells in high-glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1× penicillin G-streptomycin. Approximately 1½ week prior to viral production, thaw a vial of stock 293 cells in one 150 mm culture plate (see Fig. 1). When cells reach 70% confluency (24–72 h), split cells to three 150 mm culture plates. Forty-eight hours later, split cells to 10 × 150 mm plates. After another 48 h, split again to 30 × 150 mm plates. At this stage, either split cells to 90 × 150 mm plates and use them for AAV production, or split to the number of the plates as needed and save the remaining in −80°C (e.g., split 10 plates to 30 plates for AAV production and freeze 20 plates for future use) (see Fig. 1a). Usually, 48 h after the last split, cells should be ready for transfection. Change to fresh culture media about 1–2 h before transfection (see Note 12).

Prepare DNA-calcium-phosphate precipitate for cotransfection of the cis plasmid, AAV helper plasmid, and the adenoviral helper plasmid. For a 15 × 150 mm plate preparation, use 187.5 μg of the cis plasmid, 562.5 μg of the AAV helper plas-mid and 562.5 μg pHelper. Warm up 2.5 M CaCl2 and 2× HBS buffer at 37°C for 20 min. Mix all plasmids thoroughly in 15.2 mL H2O. Incubate at 37°C for 10 min. Add 1.68 mL of 2.5 M CaCl2 to the plasmid mixture (a final CaCl2 concentration of 250 mM). Mix well and incubate at 37°C for 5 min. Add 16.8 mL of 2× HBS to a 150 mL Corning fleaker. Slowly drop the DNA/CaCl2 mixture to 2× HBS to generate DNA-calcium-phosphate precipitate. Gently swirl the 2× HBS buffer while dropping the DNA/CaCl2 mixture. Incubate at room temperature for 15 min (see Notes 13 and 14).

Gently apply the DNA-calcium-phosphate precipitate (~2.2 mL/150 mm plate) to 293 cells drop-by-drop evenly to the entire plate while swirling the culture plate.

Around 60 h after transfection, scrape cells from 150 mm plates with a cell lifter. Split crude lysate to two 250 mL Corning centrifuge bottles. Carefully rinse off all cells from plates to the centrifuge bottles (see Note 15).

Spin at 1,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C in an IEC Centra CL3R centrifuge. Resuspend cell pellet into 10 mM Tris–HCl at 5 mL/centrifuge bottle. Rinse each centrifuge bottle with 2 mL of 10 mM Tris–HCl. Combine cell lysate into two 15 mL centrifuge tubes (7 mL/tube). Store the crude lysate in −80°C until purification.

3.2. Recombinant AAV Purification

Freeze/thaw the crude lysate (in 15 mL tubes) 8 times by rotating through a dry ice/ethanol bath (7 min/round) and a 37°C water bath (7 min/round).

Combine the crude lysate to a 50 mL tube and bring the final volume to ~21 mL with 10 mM Tris–HCl.

Sonicate the crude lysate on ice using the Misonic Sonicator at the power output of 2 for 7 min (see Note 16).

Add 2 mL of reconstituted DNase I and incubate at 37°C for 30 min (see Note 6).

Sonicate the crude lysate again under the same setting (power output 2 for 7 min).

Add 2.5 mL of 10% sodium deoxycholate and 2.1 mL of 0.25% trypsin-EDTA. Mix well. Incubate at 37°C for 30 min and then chill on ice for 20 min (see Note 17).

Add 16.9 g CsCl. Mix well. Incubate at 37°C for 20 min. Periodically shake the tube to assist CsCl dissolving (see Note 18).

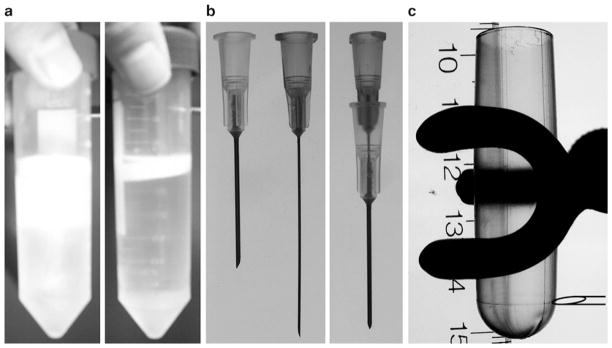

Centrifuge at 3,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C in an Eppendorf 5810R centrifuge. Carefully transfer the clear lysate to six 5.1 mL Beckman polyallomer ultracentrifuge tubes (~5 mL/ tube) (see Note 19) (see Fig. 2a).

Load the lysate to a SW55 Ti rotor and spin at 266,400 × g (53,000 rpm) for 30 h at 4°C in a Beckman-Coulter Optimal XL-80 ultracentrifuge (see Notes 7 and 20).

Assemble a self-made needle stylet by inserting a 1.5 in. 25G needle into the lumen of a 1 in. 20G needle (see Fig. 2b). Collect fractions from the bottom of the tube with the needle stylet (see Fig. 2c) (see Note 21). Identify the viral containing fractions by slot blot or quantitative PCR (see Subheading 3.3) (see Note 22).

Combine AAV-containing fractions into a new 5.1 mL Beckman polyallomer ultracentrifuge tube (see Note 21). Repeat ultracentrifugation under the same setting.

Combine fractions with the highest AAV titer from each Beckman ultracentrifuge tube and perform the third round of ultracentrifugation under the same setting (see Note 23).

Combine fractions with the highest AAV titer. Dialyze virus in three changes of AAV dialysis buffer at 4°C (4 L buffer/ change, 12–16 h/change) (see Note 24).

Fig. 2.

Self-made needle stylet and the position of needle penetration when collecting AAV fractions. (a) The solution appears turbid after CsCl is completely dissolved (left ). Cell debris forms a thin lipid-like layer at the top after spinning (right). (b) Left, a 1 in. 20G needle and a 1.5 in. 25G needle; Right, assembled needle stylet. (c) A horizontal line is visible at ~0.5 cm above the bottom of a 5.1 mL Beckman polyallomer ultracentrifuge tube. When pulling fractions, insert the needle stylet horizontally into the centrifuge tube at the level of this line. Stop when the needle tip reaches at the center. Face the needle tip opening upward. Start collecting fractions.

3.3. Titer Determination and Quality Control

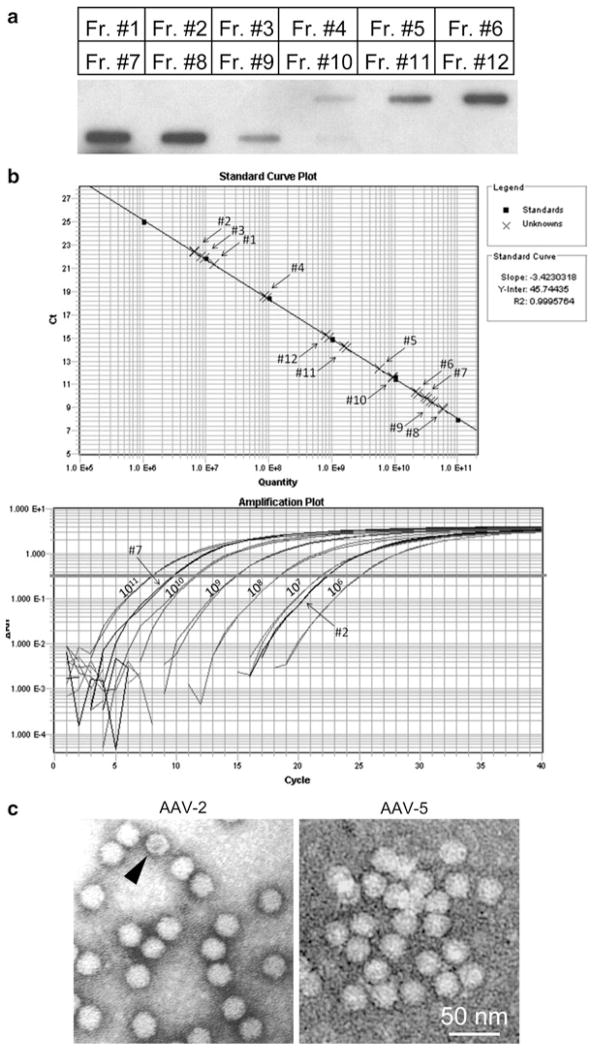

Determine AAV titer by slot blot. Denature samples (1, 5, and 10 μL in duplicates) and plasmid copy number controls (107–1011 copies) in 50 μL AAV digestion buffer at 100°C for 10 min. Immediately chill on ice and bring up volume to 400 μL with the digestion buffer. Load onto a Hybond-N plus membrane with a Bio-Dot SF manifold microfiltration apparatus. After blotting, crosslink DNA to the membrane with UV irradiation. Prehybridize the membrane in 10 mL slot blot hybridization solution in a Techne roller bottle hybridization oven at 37°C for 2 h. Hybridize the membrane with a 32P-labeled transgene-specific probe in the slot blot hybridization solution at 37°C for 5 h. Wash the membrane at 37°C in 2× SSC/1% SDS (2 × 15 min). Wash the membrane in 0.5× SSC/1% SDS (2 × 15 min). Wash the membrane in 0.1× SSC for 15 min. Expose the membrane in an X-ray film for 2 h (or overnight). Develop the film and determine the viral genome particle titer by comparing the intensity of the viral sample bands to those of the copy number controls.

Determine AAV titer by quantitative PCR. Denature viral samples (2 μL in triplicates) and plasmid copy number controls (106–1011 copies/μL) in 50 μL of AAV PCR alkaline digestion buffer at 100°C for 10 min. Immediately chill on ice and add 50 μL of AAV PCR neutralization buffer. Mix well and use as the PCR template. Prepare the PCR reaction mixture on ice in a 96-well reaction plate. Each reaction mixture (20 μL/well) contains 10 μL of Fast SYBR green PCR master mixture, 0.3 μL of 10 μM forward primer, 0.3 μL of 10 μM reverse primer (see Table 1), 1 μL of the PCR template, and 8.4 μL of PCR quality water. Warm up the ABI 7900HT real-time PCR machine for 5 min. Select absolute quantification for the study type and SYBR for the detector. Designate the sample, standard (copy number control), and control (no template) wells. Turn on the ROX passive reference. Set the thermal cycler condition (see Table 2). Load the 96-well plate. Start the run. Obtain the quantity mean from the on-screen result table and calculate the viral genome copy number titer (see Note 25).

Determine AAV quality by electron microscope. Place one drop of purified AAV on a 200 mesh carbon-coated copper grid for 5 min. Gently wash in ultra pure water for four times. Apply one drop of 1% uranyl acetate on the sample. Air dry for 5 min. Visualize viral particles using a JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope (see Fig. 3).

Determine the endotoxin level with the LAL assay. Reconstitute control standard endotoxin (CSE) with LAL reagent water provided with the EndoSafe LAL gel clot test kit. The reconstituted CSE is stable for 4 weeks at 4°C. Place 200 μL sample (or control) to each LAL gel clot reaction tube. Vortex briefly. Incubate at a 37°C water bath for 60 min. A positive result is defined as the formation of a clot that retains its integrity (either at the bottom or slide down to the side of the tube) when the tube is inverted 180°. The formation of a viscous solution which breaks apart and slides down the side of the tube is considered negative (see Note 26).

Table 2.

Conditions for quantitative PCR

| Stage 1 (initial denaturation) | Stage 2 (amplification reaction) | Stage 3 (dissociation curve; optional) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal profile | 95°C, 20 s | 95°C, 5 s → 60°C, 20 s; ×40 | 95°C, 15 s →60°C, 15 s → 95°C, 15 s |

| Autoincrement | +0, +0 | +0, +0 | +0, +0 |

| Ramp rate | 100% | 100% | Final 95°C is 2%; the others 100% |

| Data collection | None | At 60°C step | At slope between 60 and 95°C |

Fig. 3.

AAV vector genome titer determination and viral quality examination. (a) A representative slot blot from a first round CsCl ultracentrifugation. Fractions (Fr.) 5–8 usually contain most of the virus. (b) Representative results from quantitative PCR. The top is the quantification curve. The bottom is the amplification curve. Fractions are marked in numbers. (c) Representative electron microscopic images of AAV-2 (left) and AAV-5 (right). Scale bar applies to both images. Arrowhead indicates a partially packaged virus.

Acknowledgments

The protocols were developed with the grant support from the National Institutes of Health (AR-49419 and HL-91883 to DD), the Muscular Dystrophy Association (DD), and the Parent Project for Muscular Dystrophy. We thank Duan lab members for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Latent infection of 293 cells by wild type AAV may result in wild type AAV contamination in purified vector stocks (30). We suggest checking wild type AAV contamination periodically in 293 cells (31). Although 293 cells remain the mainstay for laboratory-scale AAV production, different producer cell lines have been developed for industrial-scale manufacturing. These cells contain integrated AAV rep and cap genes. Some also carry the vector genome. AAV production is initiated with a helper virus (such as adenovirus and herpes simplex virus) infection (reviewed in refs. (22–24, 26)).

All the plasmids (including adenovirus helper plasmid, AAV helper plasmid, and cis plasmid) are prepared by the triton-lysis/ CsCl-ethidium bromide density gradient centrifugation method. We have found that plasmids prepared this way give the highest AAV yield (32). The vast majority of AAV variants are based on the AAV-2 ITR. Because of the high recombination nature of the ITR, we strongly suggest to propagate the cis plasmid in the SURE cells (Stratagene) or Stbl2 cells (Gibco-Invitrogen).

Adenovirus contamination has been a major concern of AAV stock. This hurdle is now overcome with the development of helper virus-free AAV production system. In this system, a helper plasmid is used to express adenoviral virus-associated RNA (VA RNA), E2a, and E4 genes. Since 293 cells express adenoviral E1a and E1b genes, all adenoviral helper function is now reconstituted. This technology has completely eliminated the need of adenovirus coinfection in AAV preparation. We have used the Stratagene pHelper plasmid, which expresses adeno-viral E2a, E4, and VA RNA (33). Several similar adenoviral helper plasmids have also been published including pXX6 (available at the UNC Vector Core Facility, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC) and pDG (PlasmidFactory, Heidelberg, Germany) (34–36). Besides adenoviral helper genes, pDG also carries AAV-2 rep and cap genes (35).

For most serotypes (or AAV variants), a single AAV helper plasmid is used to express both cap and rep genes. The selection of the cap gene is determined by the intended serotype. However, most AAV helper plasmids express the AAV-2 rep gene (this is because the AAV-2 ITR is often used as the replication/packaging signal). Two exceptions are AAV-5 and 6. In these cases, two AAV helper plasmids are used. For AAV-5, one helper expresses the AAV-2 rep gene and the other expresses the AAV-5 rep and cap genes (37, 38). For AAV-6, one helper expresses the AAV-2 rep gene under the mouse metallothionein (MT) promoter and the other expresses AAV-6 cap gene under the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (39). The AAV-2 helper plasmid (pAAV-RC) can be purchased from Stratagene. The helper plasmids for AAV-1 to 8 can be purchased from PlasmidFactory. We have obtained AAV-5 helper plasmids (pAV5-Trans and pAV2-Rep) from Dr. John F. Engelhardt (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). We have obtained AAV-6 helper plasmids (pMT-Rep2 and pCMV-Cap6) from Dr. A. Dusty Miller (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Institute, Seattle, WA). We have obtained AAV-1, 7, 8, and 9 helper plasmids from Dr. James M. Wilson (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA).

Since pH affects transduction efficiency, it is highly suggested to double check pH of 2× HBS buffer before each usage. After thawing the buffer, make sure to mix well by inverting the tube several times.

DNase I (from the bovine pancrease) is used to release AAV particles from the nucleus. Reconstitute DNase I by adding 4 mL of double distilled water to one vial of lyophilized powder. Mix well before use. Besides DNase I, one can also use Benzonase (25,000 Unit). A recent study suggests that for AAV serotype-1, 8, and 9, mature viral particles are also released to the culture medium. For these serotypes, high quantity of biologically active AAV virions can be directly harvested from the culture medium (40).

We have also used the Beckman L-60, Beckman L8-70, and Sorvall Discovery SE100 ultracentrifuges and the Beckman SW50.1 and Sorvall AH650 rotors. It is important to match the centrifuge speed with the rotor.

Others have used the Beckman ultraclear ultracentrifuge tube. This type of tube may lead to better visualization of the virus band (e.g., during adenovirus preparation). However, we find the ultraclear ultracentrifuge tube is difficult to penetrate with a needle. Since the AAV band is often not detectable by eyeballing, we recommend use of the polyallomer tube.

Besides Pierce’s Slide-A-Lyze dialysis cassette, we have also obtained excellent results with self-prepared 12–14,000 MWCO dialysis tubing. Briefly, boil dialysis tubing (6.4 mm) in a solution containing 238 mM NaHCO3 and 1 μM EDTA for 1 h. Wash extensively with tap water until pH of the washout reaches that of tap water. Store the dialysis tubing at 4°C in a dark bottle containing 0.04% sodium azide.

We use 107–1011 copies and 106–1011 copy/μL of the vector genome in slot blot and quantitative PCR, respectively. The copy number control is made with the cis plasmid according to the length (in bp) and the concentration (in ng/μL) of the plasmid. The formula for calculating single-stranded AAV copy number is: [Plasmid concentration × 1.2 × 1015]/[(plasmid DNA length × 607.4) + 157.9]. Store the copy number control in −20°C in 50 μL aliquots. Avoid repeated freeze/thaw.

Uranyl acetate is highly toxic and radioactive. Handle with care. Dilute the stock with double-distilled water to 1% working solution and filter through a 0.45 μm filter. Store in dark at 4°C.

It is critical to double check cell confluency prior to plasmid transfection (see Fig. 1b). We perform transfection at 70% con-fluency. Differences in cell confluency (e.g., 60 or 80%) may result in suboptimal transfection and low AAV yield.

The type/number of the plasmids may vary. For AAV-1, 2, 7, 8 and 9, we use triple plasmid transfection (the cis plasmid at 12.5 μg/150 mm plate, the pHelper at 37.5 μg/150 mm plate, and a rep-cap containing AAV helper plasmid at 37.5 μg/150 mm plate). Four plasmids are used in AAV-5 and 6 preparations. For AAV-5, it includes the cis plasmid at 12.5 μg/150 mm plate, the pHelper at 37.5 μg/150 mm plate, an AAV-5 rep-cap plasmid at 37.5 μg/150 mm plate and an AAV-2 rep plasmid at 12.5 μg/150 mm plate. For AAV-6, it includes the cis plasmid at 12.5 μg/150 mm plate, the pHelper at 37.5 μg/150 mm plate, the pMT-Rep2 at 12.5 μg/150 mm plate and the pCMACap6 at 37.5 μg/150 mm plate. If adenoviral helper function and AAV helper function are combined in one plasmid (such as in pDG), only two plasmids will be needed (the pDG and a cis plasmid) for trans-fection (35). We have consistently observed similar transfection efficiency using either three or four plasmids.

Here, we described the calcium phosphate coprecipitation method. Under optimal condition, transfection efficiency reaches 90% (see Fig. 1c). However, depending on the conditions used (such as the pH of the solution, the size of the precipitates), transfection efficiency can be dramatically reduced (see Fig. 1d). We recommend routinely monitoring calcium phosphate precipitate on a coverslip using a phase contrast microscope. Under optimal condition, one should see uniform fine precipitates. Large aggregates often lead to poor transfection and low AAV yield. We also recommend monitoring the quality of the transfec- and 2× HBS) with a pilot test using tion reagents (such as CaCl2 a reporter gene plasmid. Alternatively, a separate 35 mm plate of 293 cells (from the same split of 150 mm plates) should be transfected with the same transfection cocktail and examined for transfection efficiency (e.g., by histochemical staining for the LacZ and AP genes, or by immunofluorescence staining for a particular target gene). Some investigators have also spiked one to 20–100th of a GFP plasmid that does not contain AAV ITR as internal control to monitor transfection efficiency. The protocol described here has been optimized for 15 × 150 mm plate transfection. Besides calcium phosphate coprecipitation method, others have also used polyethylenimine coprecipitation and cationic lipid transfection methods (reviewed in ref. (27)).

From 15 × 150 mm plates, we usually get ~350 mL crude lysate. Cells usually pellet at the bottom of the 250 mL Corning centrifuge bottle. We rinse off the remaining cells from the plates with the supernatant from the centrifuge bottle.

Clean the sonicator probe with 70% ethanol followed by rinse with 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) before each use. Make sure to submerge the probe into the crude lysate so that the tip of the probe is ~2.5 cm above the bottom of the 50 mL tube.

Final volume will be approximately 27.6 mL prior to the addition of CsCl.

The buoyant density of AAV is between 1.32 and 1.47 g/mL in CsCl gradient (41). The lighter particles (<1.39 g/mL) represent empty or partially packaged virions (42). The fully packaged AAV particles have a density of 1.39–1.42 g/mL. The most infectious AAV particles are found at the density of 1.41 g/mL. Heavy particles (>1.42 g/mL) seem to associate with an unknown high molecular weight protein and their infectivity is significantly reduced (43, 44). Adding 16.9 g CsCl to 27.6 mL crude lysate (0.613 g/mL) results in a final CsCl contraction of 1.41 g/mL prior to ultracentrifugation.

After centrifugation, cell debris forms a thin lipid-like layer at the top (see Fig. 2a). If not proceed to ultracentrifugation right away, the clear lysate can be stored at 4°C for up to 1 week.

For Beckman SW50.1 and Sorval AH650 rotors, we suggest spinning at 198,000 × g (46,000 rpm) for 40 h.

We usually insert the self-made needle stylet at the level of the horizontal line on the Beckman ultracentrifuge tube (see Fig. 2c). To get consistent results, it is important to always enter at the same level. Position the needle tip opening to face up. Remove the 25G needle. Discard the first 14 drops and then collect 12 drops (~750 μL) /fraction. From each 5.1 mL Beckman ultracentrifuge tube, we usually get 12 fractions. AAV often appears in fractions 5–8.

For the first and the second rounds of ultracentrifugation, it is not necessary to include the copy number controls in slot blot or quantitative PCR.

Prior to the third round of ultracentrifugation, we usually add 200 mg CsCl to 5 mL of combined viral fractions collected from the second round of ultracentrifugation. Addition of CsCl is necessary to maintain the isopycnic gradient during the third round of ultracentrifugation. From 15 to 150 mm plates, we get ~30 mL lysate for the first round of ultracentrifugation. From the first round of ultracentrifugation, we collect ~15 mL of AAV containing fraction (enough to fill three 5.1 mL Beckman ultracentrifuge tubes). After the second round of ultracentrifugation, we usually get ~3 mL of AAV containing fraction. To have enough volume for the third round of ultracentrifugation, we usually start with 150 × 150 mm plates AAV preparation. This will generate ~30 mL of AAV containing fraction after two rounds of ultracentrifugation. However, if the preparation started with 15 × 150 mm plates, the volume from the second round of ultracentrifugation will be less than 5 mL and not enough to fill up a single 5 mL ultracentrifuge tube. In this case, we suggest using CsCl/10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) (0.613 g/mL) to bring up the final volume to 5 mL.

Double check to make sure the dialysis tubing is not leaking. Remember to place a magnetic stir bar to gently agitate the dialysis buffer. We usually get a yield of 5 × 1012 to 1 × 1013 viral genome particles/mL of AAV vectors.

If PCR templates are not used immediately, they can be stored in 20 μL aliquots at −20°C. Each aliquot is only good for one use. Make sure to tightly seal the wells with an adhesive film applicator and do not taint the surface of the adhesive film. After running the PCR reaction, check the standard curve (the R2 should be higher than 0.95) and the dissociation curve (all reactions should point to a single peak). Ideally, the standard deviation of the viral samples should be less than one tenth of the titer.

It is critical to use depyronated pipette tips and dilution tubes provided with the EndoSafe LAL gel clot test kit. Prior to the use of each new lot of the kit, validate the endpoint control to confirm the listed sensitivity. For each new type of biological sample, perform a positive product inhibition control to determine whether there are proteins/chemicals in the sample that may inhibit the gel clot reaction. Always include a positive and a negative control. The LAL assay requires 200 μL sample volume for each sample. To avoid wasting AAV virus, viral stock can be diluted with the LAL reagent water prior to the assay. After removing the tube from the 37°C water bath, examine the clot formation immediately (within 2 min). Waiting too long will lead to false readings.

References

- 1.Atchison RW, Casto BC, Hammon WM. Adenovirus-Associated Defective Virus Particles. Science. 1965;149:754–6. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3685.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flotte TR, Berns KI. Adeno-associated virus: a ubiquitous commensal of mammals. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:401–7. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnepp BC, Jensen RL, Chen CL, Johnson PR, Clark KR. Characterization of adeno-associated virus genomes isolated from human tissues. J Virol. 2005;79:14793–803. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14793-14803.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duan D, Sharma P, Yang J, Yue Y, Dudus L, Zhang Y, Fisher KJ, Engelhardt JF. Circular Intermediates of Recombinant Adeno–Associated Virus have Defined Structural Characteristics Responsible for Long Term Episomal Persistence in Muscle. J Virol. 1998;72:8568–77. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8568-8577.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huser D, Gogol-Doring A, Lutter T, Weger S, Winter K, Hammer EM, Cathomen T, Reinert K, Heilbronn R. Integration preferences of wildtype AAV-2 for consensus rep-binding sites at numerous loci in the human genome. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000985. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senapathy P, Carter BJ. Molecular cloning of adeno-associated virus variant genomes and generation of infectious virus by recombination in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:4661–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samulski RJ, Srivastava A, Berns KI, Muzyczka N. Rescue of adeno-associated virus from recombinant plasmids: gene correction within the terminal repeats of AAV. Cell. 1983;33:135–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter BJ. Adeno-associated virus and the development of adeno-associated virus vectors: a historical perspective. Mol Ther. 2004;10:981–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendell JR, Rodino-Klapac LR, Rosales-Quintero X, Kota J, Coley BD, Galloway G, Craenen JM, Lewis S, Malik V, Shilling C, Byrne BJ, Conlon T, Campbell KJ, Bremer WG, Viollet L, Walker CM, Sahenk Z, Clark KR. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2D gene therapy restores alpha-sarcoglycan and associated proteins. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:290–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.21732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, Pugh EN, Jr, Mingozzi F, Bennicelli J, Banfi S, Marshall KA, Testa F, Surace EM, Rossi S, Lyubarsky A, Arruda VR, Konkle B, Stone E, Sun J, Jacobs J, Dell’Osso L, Hertle R, Ma JX, Redmond TM, Zhu X, Hauck B, Zelenaia O, Shindler KS, Maguire MG, Wright JF, Volpe NJ, McDonnell JW, Auricchio A, High KA, Bennett J. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2240–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cideciyan AV, Hauswirth WW, Aleman TS, Kaushal S, Schwartz SB, Boye SL, Windsor EA, Conlon TJ, Sumaroka A, Roman AJ, Byrne BJ, Jacobson SG. Vision 1 year after gene therapy for Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:725–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0903652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bainbridge JW, Smith AJ, Barker SS, Robbie S, Henderson R, Balaggan K, Viswanathan A, Holder GE, Stockman A, Tyler N, Petersen-Jones S, Bhattacharya SS, Thrasher AJ, Fitzke FW, Carter BJ, Rubin GS, Moore AT, Ali RR. Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2231–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarty DM. Self-complementary AAV vectors; advances and applications. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1648–56. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou X, Zeng X, Fan Z, Li C, McCown T, Samulski RJ, Xiao X. Adeno-associated virus of a single-polarity DNA genome is capable of transduction in vivo. Mol Ther. 2008;16:494–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong L, Zhou X, Li Y, Qing K, Xiao X, Samulski RJ, Srivastava A. Single-polarity Recombinant Adeno-associated Virus 2 Vector-mediated Transgene Expression In Vitro and In Vivo: Mechanism of Transduction. Mol Ther. 2008;16:290–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh A, Yue Y, Lai Y, Duan D. A hybrid vector system expands aden-associated viral vector packaging capacity in a transgene independent manner. Mol Ther. 2008;16:124–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon I, Schaffer DV. Designer gene delivery vectors: molecular engineering and evolution of adeno-associated viral vectors for enhanced gene transfer. Pharm Res. 2008;25:489–99. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9431-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandenberghe LH, Wilson JM, Gao G. Tailoring the AAV vector capsid for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2009;16:311–9. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Z, Asokan A, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated Virus Serotypes: Vector Toolkit for Human Gene Therapy. Mol Ther. 2006;14:316–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Wilson JM. New recombinant serotypes of AAV vectors. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:285–97. doi: 10.2174/1566523054065057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Virag T, Cecchini S, Kotin RM. Producing recombinant adeno-associated virus in foster cells: overcoming production limitations using a baculovirus-insect cell expression strategy. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:807–17. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clement N, Knop DR, Byrne BJ. Large-scale adeno-associated viral vector production using a herpesvirus-based system enables manufacturing for clinical studies. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:796–806. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Xie J, Xie Q, Wilson JM, Gao G. Adenovirus-adeno-associated virus hybrid for large-scale recombinant adeno-associated virus production. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:922–9. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zolotukhin S. Production of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:551–7. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cecchini S, Negrete A, Kotin RM. Toward exascale production of recombinant adeno-associated virus for gene transfer applications. Gene Ther. 2008;15:823–30. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorne BA, Takeya RK, Peluso RW. Manufacturing recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors from producer cell clones. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:707–14. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright JF. Transient transfection methods for clinical adeno-associated viral vector production. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:698–706. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham FL, Smiley J, Russell WC, Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human ade-novirus type 5. J Gen Virol. 1977;36:59–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Louis N, Evelegh C, Graham FL. Cloning and sequencing of the cellular-viral junctions from the human adenovirus type 5 transformed 293 cell line. Virology. 1997;233:423–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duan D, Fisher KJ, Burda JF, Engelhardt JF. Structural and functional heterogeneity of integrated recombinant AAV genomes. Virus Res. 1997;48:41–56. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(96)01425-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katano H, Afione S, Schmidt M, Chiorini JA. Identification of adeno-associated virus contamination in cell and virus stocks by PCR. Biotechniques. 2004;36:676–80. doi: 10.2144/04364DD01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heilig JS, Elbing KL, Brent R. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. Unit 1. Chapter 1. 2001. Large-scale preparation of plasmid DNA; p. 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsushita T, Elliger S, Elliger C, Podsakoff G, Villarreal L, Kurtzman GJ, Iwaki Y, Colosi P. Adeno-associated virus vectors can be efficiently produced without helper virus. Gene Ther. 1998;5:938–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimm D, Kay MA, Kleinschmidt JA. Helper virus-free, optically controllable, and two-plasmid-based production of adeno-associated virus vectors of serotypes 1 to 6. Mol Ther. 2003;7:839–50. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grimm D, Kern A, Rittner K, Kleinschmidt JA. Novel tools for production and purification of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2745–60. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.18-2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao X, Li J, Samulski RJ. Production of high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in the absence of helper adenovirus. J Virol. 1998;72:2224–32. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2224-2232.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan D, Yan Z, Yue Y, Ding W, Engelhardt JF. Enhancement Of Muscle Gene Delivery With Pseudotyped AAV-5 Correlates With Myoblast Differentiation. J Virol. 2001;75:7662–71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7662-7671.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan Z, Zak R, Luxton GW, Ritchie TC, Bantel-Schaal U, Engelhardt JF. Ubiquitination of both adeno-associated virus type 2 and 5 capsid proteins affects the trans-duction efficiency of recombinant vectors. J Virol. 2002;76:2043–53. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2043-2053.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen JM, Halbert CL, Miller AD. Improved adeno-associated virus vector production with transfection of a single helper adenovirus gene, E4orf6. Mol Ther. 2000;1:88–95. doi: 10.1006/mthe.1999.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vandenberghe LH, Xiao R, Lock M, Lin J, Korn M, Wilson JM. Efficient serotype-dependent release of functional vector into the culture medium during AAV manufacturing. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:1251–7. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de la Maza LM, Carter BJ. Molecular structure of adeno-associated virus variant DNA. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:3194–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torikai K, Ito M, Jordan LE, Mayor HD. Properties of light particles produced during growth of Type 4 adeno-associated satellite virus. J Virol. 1970;6:363–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.6.3.363-369.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipps BV, Mayor HD. Characterization of heavy particles of adeno-associated virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1982;58(Pt 1):63–72. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-58-1-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de la Maza LM, Carter BJ. Heavy and light particles of adeno-associated virus. J Virol. 1980;33:1129–37. doi: 10.1128/jvi.33.3.1129-1137.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]