Abstract

Background

Currently, limited mouse models that mimic the clinical course of castrate resistant prostate development currently exist. Such mouse models are urgently required to conduct pre-clinical studies to assist in the understanding of disease progression and the development of rational therapeutic strategies to treat castrate resistant prostate cancer.

Methods

Wild type intact FVB male mice were injected by subcutaneous injection with Myc-CaP cells to establish androgen sensitive Myc-CaP tumors. Tumor bearing mice were castrated and resulting tumors serially passaged in pre-castrated FVB male mice to produce a bone fide Myc-CaP castrate resistant tumor.

Results

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that initial androgen sensitive Myc-CaP tumors had strong nuclear transcriptional active androgen receptor expression, as indicated by marked c-MYC staining and were highly proliferative. Castration of tumor bearing animals resulted in cytoplasmic relocation of androgen receptor concurrent with loss of transcriptional activity and tumor proliferation. Serial passaging of castrate refractory Myc-CaP in pre-castrated male FVB mice resulted in the development of a bona fide castrate resistant Myc-CaP tumor which pheno-copied the original androgen sensitive parental Myc-CaP tumor.

Conclusions

Developing a murine castrate transplant resistant tumor model that mimics the clinical course of human castrate resistant prostate cancer will create better opportunities to understand the development of castrate resistant prostate cancer and also allow for more rapid pre-clinical studies to stratify rational novel therapies for this lethal form of prostate cancer.

Keywords: mouse models, prostate cancer, MYC, castrate resistant prostate cancer

Introduction

A major cause of mortality and morbidity in men world wide is prostate cancer, or more specifically, the lethal form castrate resistant prostate cancer. The research field, in this case prostate cancer, relies on the use of pre-clinical animal models to understand disease development and progression, and to also strategize novel rational therapeutic interventions. Over the years, multiple xenograft and genetically engineered mouse models of prostate cancer have been generated to attempt to bridge our success of bench to bedside medicine. The Prostate Cancer Foundation, in 2007, held a Prostate Cancer Models Working Group to discuss relevant issues in prostate cancer animal models [1].

Within the last decade two transgenic mouse models were reported which had specific genetic manipulation highly relevant to the development and progression of human prostate cancer, the PtenL/L;C+ model [2], and myc model [3] of prostate cancer. These two mouse models give rise to mPIN at approximately 6 weeks and 2 weeks of age, respectively and progress to invasive adenocarcinoma at approximately >6 months of age. Array data collected from both models revealed a molecular signature that closely mimics human prostate cancer [2,3]. A further advantage was the generation of cell lines from these mouse models, Pten-CaP [4] and Myc-CaP [5], allowing for the generation of transplant tumor models in an immunocompetent host. This approach has been greatly utilized in the Eμ-myc model of B cell lymphoma [6,7] and allows for rapid pre-clinical studies. The PtenL/L;C+ model was reported to develop castrate resistant disease post surgical castration [2] and consequent cell lines had been developed and reported [8]. Currently to our knowledge, no further development of an in vivo castrate resistant tumor model from the myc mouse model has been reported. The original report from Ellwood-Yen et al. [3] demonstrated that castration of myc mice with developed PIN reverted progression to cancer, but castration of mice with prostate cancer resulted in residual quiescent tumor burden that was non-proliferating and lacked nuclear androgen receptor staining and myc transgene expression, though no evidence of progression to castrate resistant prostate cancer was documented [3]. Further work with the Myc-CaP cell line found that expressing an androgen-independent myc was sufficient to rescue in vitro, but not in vivo androgen independent growth [5], though knockdown of Pten could rescue androgen independent Myc-CaP tumor growth in vivo [4]. Interestingly, it was observed that Myc-CaP tumor growth >500 mm3 did posses the potential to regain proliferation post castration. Further, when tumors that increased in size were harvested and placed in short term culture without androgen they were found to express c-Myc mRNA levels similar to the parental androgen dependent Myc-CaP cells [5].

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Reagents

The Myc-CaP cell line [5] was a generous gift from Dr. Charles Sawyers and were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Bicalutamide (casodex) for in vivo experiments was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Ontario, Canada). Stock solution was made in distilled water (2.5 mg/ml) and stored at 4°C until used in experiments.

Development of Myc-CaP Transplant Models of Prostate Cancer

The Institute Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) approved all mouse protocols used in this study. All mice were purchased from NCI Frederick (MD, USA).

Development of Myc-CaP/AS (Androgen Sensitive) and Myc-CaP/CR (Castrate Resistant) Tumor Banks

Wild-type FVB mice were injected subcutaneous with Myc-CaP cell lines (1 × 106 cells/mouse). Tumor bearing mice were sacrificed and Myc-CaP/AS tumors from non-castrated mice were collected, or mice were surgically castrated to produce castrate resistant tumors. Myc-CaP/CR tumors were passaged through four rounds of surgically castrated wild-type FVB male mice before they were believed to be bona fide castrate resistant tumors. Tumor proliferation was monitored by serial caliper measurement.

In vivo therapy experiments

Six-week old male FVB mice were anesthetized using isoflourane and surgically castrated. Ten-days post castration, Myc-CaP castrate resistant tumor pieces (∼20–30 mm2) were subcutaneously grafted to these mice and left for an additional 10 days before being treated with bicalutamide at a dose of 25 mg/kg/day or 50 mg/kg/day by oral gavage. Control mice were treated with a corresponding volume of distilled water.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue (4 μm) were stained with primary antibodies to detect androgen receptor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Ki67 (Thermo Scientific), c-MYC (Epitomics). All sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C and then incubated with ImmPRESS™ reagent kit HRP anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Vector Laboratories). Staining was developed by incubation with 3,3′-diaminobenzide (Dako), and counterstained with hematoxylin. Images were captured using a Scanscope XT system (Aperio Imaging) and analyzed using Imagescope software (Aperio).

Staining Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Ki-67 immuno-staining quantitation was performed using Image J software. Myc-Cap tumor doubling times were calculated by non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism software. Statistical significance between treatment groups was determined using a Student's t test. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results and Discussion

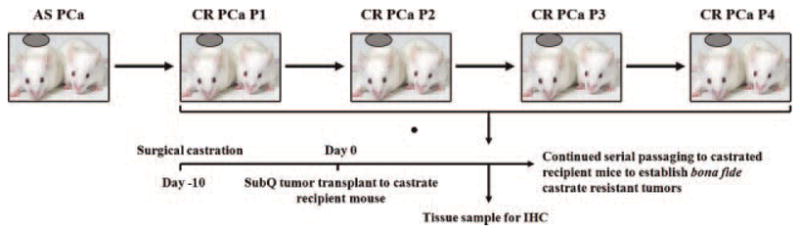

In this present study, we wanted to identify if indeed androgen sensitive Myc-CaP tumors developed in intact mice did progress to a bona fide castrate resistant phenotype, and if so does the development/progression to castrate resistance reflect the clinical course of castrate resistant prostate cancer development. We initially examined the ability of Myc-CaP cells to develop androgen sensitive tumors within the major graft sites utilized with in vivo mouse models. Figure 1 demonstrates the schema used to develop a bona fide castrate resistant Myc-CaP tumor in vivo. Mice bearing ≥500 mm2 established subcutaneous androgen sensitive Myc-CaP tumors were castrated and monitored over 1 month at which time proliferating tumors where excised and viable tissue was transplanted to pre-castrated male mice for a serious of four passages.

Fig. 1.

Schema for the generation of an in vivo Myc-CaP castrate resistant tumor model of prostate model. Intact FVB male mice were grafted with 1 × 106 Myc-CaP cells subcutaneous and grown to ≥500 mm2 determined by serial caliper measurement. Once tumors were ≥500 mm2, mice were surgically castrated and monitored for 1-month post castration. Tumors that demonstrated proliferation as determined by caliper measurements were surgically excised and transplanted to castrated FVB male mice for a total of four serial passages. At the time of transplant, tumor tissue was also fixed in 10% normal buffered formalin for immunhistochemical analysis.

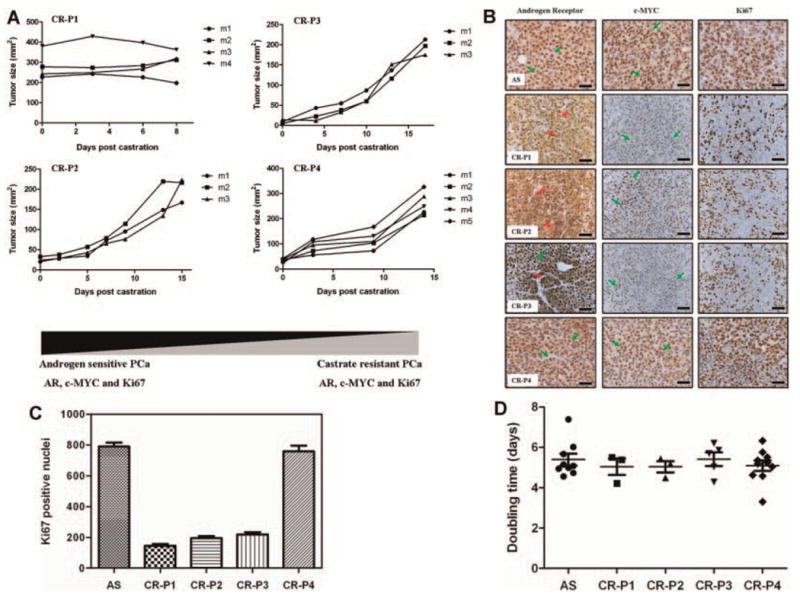

Figure 2A demonstrates that Myc-CaP tumors are capable of proliferating in castrated mice post engraftment (Fig. 2A, CR-P1) and further, gain the ability to be successfully grafted and proliferate in pre-castrated mice (Fig. 2A, CR-P2-P4). As previously shown [5], we established Myc-CaP androgen sensitive tumors by subcutaneous injection of 1 × 106 Myc-CaP cells to intact male mice (Fig. 2B, top panel). Myc-CaP androgen sensitive tumors displayed abundant nuclear expression of androgen receptor that was transcriptionally active as indicated by the increased expression of the androgen dependent transgene c-MYC. Myc-CaP tumors were also highly proliferative as indicated by IHC staining for the proliferation marker Ki67 (Fig. 2B and C). Figure 2B further demonstrates that castration of tumor bearing mice and subsequent passaging of tumor to pre-castrated mice as indicated by IHC staining, highly mimics the clinical progression of androgen sensitive prostate to castrate resistant prostate cancer. That is, as shown in panels CR-P1 and CR-P2 following castration, AR is located to the cytoplasm (red arrows). Further, because of AR translocation to the cytoplasm, lesser transcriptional activity occurs as indicated by loss of c-MYC staining concurrent with a decrease in proliferation as indicated by less Ki67 staining and over all tumor size (Fig. 2C). At passage 3 (Fig. 2B panel CR-P3) a heterogeneous phenotype is indicated by nuclear recapture of AR (green arrow) while other tumor cells still have greater AR cytoplasmic staining (red arrow). Tumor cells started to display nuclear staining for c-MYC (green arrows) indicating AR transcriptional activity though tumor proliferation was still decreased as shown by Ki67 staining and tumor size (Fig. 2B panel CR-P3, Fig. 2C). Excitingly, by passage 4 of these tumors to castrated mice it was evident that these Myc-CaP tumors indeed phenocopy the IHC staining of Myc-CaP tumors in their intact mice counterparts. Figure 2B (panel CR-P4) clearly demonstrates that these tumors have progressed to a castrate resistant phenotype as indicated by recapturing AR nuclear localization (green arrows) as well as its down stream transcriptional target, c-MYC (green arrows) and increases in tumor proliferation (Ki67 IHC) and tumor size (Fig. 2B CR-P4, Fig. 2C). Non-linear regression analysis revealed that tumor doubling time was similar between each passage (Fig. 2D) and raises and interesting question of signaling pathway compensation in the absence of AR transactivation.

Fig. 2.

A: Myc-CaP tumor growth curves. Each line represents an individual tumor bearing mouse. B: Immunohistochemical staining of 4 μM paraffin embedded Myc-CaP tumor tissue samples pre- and post-castration. Antigen retrieval was performed in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer under microwave-heated conditions. Primary antibodies used were androgen receptor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Ki67 (Thermo Scientific), c-MYC (Epitomics). All sections were initially blocked with horse serum (Vector Laboratories) before incubation overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C and then incubated with ImmPRESS™ reagent kit HRP secondary IgG antibodies (Vector Laboratories). Staining was developed by incubation with 3,3′ -diaminobenzide (Dako), and counterstained with hematoxylin. Images were captured using a Scanscope XT system (Aperio Imaging) and analyzed using Imagescope software (Aperio). AS, androgen sensitive; CR-P, castrate resistant passage number. Magnification (40×); Scale bar = 50 μM. C: Quantitation of Ki-67 IHC staining from Figure 2A using image J software. D: Non-linear regression analysis of Myc-CaP tumor doubling time for each individual passage from Figure 2A using GraphPad Prism software. Sample number for Figure 2C and D were; AS n = 9, CR-P1 n = 3, CR-P2 n = 3, CR-P3 n = 5, CR-P4 n = 10.

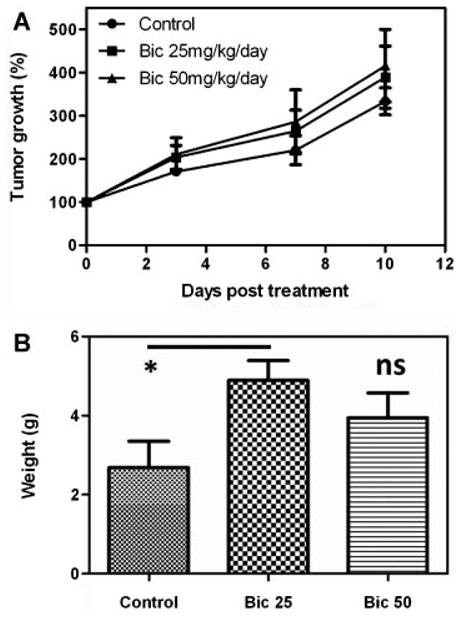

We next investigated the sensitivity of Myc-CaP/CR tumors to the AR antagonist, bicalutamide (casodex). We treated castrated FVB male mice bearing subcutaneous Myc-CaP/CR tumors by oral gavage with a daily dosing schedule of 25 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg. Surprisingly, tumor growth was not inhibited by bicalutamide treatment (Fig. 3A). Conversely, bicalutamide treatment with 25 mg/kg/day significantly increased endpoint tumor weights (P = 0.027), whereas bicalutamide treatment with 50 mg/kg/day increased tumor weight, though was not significant (P = 0.215) compared to control treated mice (Fig. 3B). This resistance to bicalutamide is attributed to the amplification of AR in the Myc-CaP cell line, which was previously documented [5]. Increased expression of AR primarily through gene amplification [9] is common in castrate resistant prostate cancer and is sufficient to mediate resistance to bicalutamide therapy in mouse xenograft models [10,11].

Fig. 3.

Surgically castrated male FVB mice were grafted subcutaneously with Myc-CaP/CR tumor pieces (∼20–30 mm2). Tumor bearing mice were treated daily with control (distilled water) (n = 4), 25 mg/kg bicalutamide (n = 6) or 50 mg/kg bicalutamide (n = 5) by oral gavage. A: Tumor growth was monitored by serial caliper measurements. B: At the experiments conclusion all tumors were excised and weighed to determine final tumor weights. *P = 0.027, ns = not significant.

Overall, we demonstrate the development of a novel murine transplant model of castrate resistant prostate cancer that initially undergoes a latency period (possibly quiescent low proliferating tumors as documented in the transgenic myc model [3]) before progressing to a hormone refractory state, as indicated by these tumors ability to proliferate in low androgen levels, and finally progressing to a castrate resistant phenotype. This transition closely follows the course of progression to castrate resistant prostate cancer in the clinic.

Development of castrate resistant tumor models in immunocompentent mice will allow for a closer understanding of not only the development and progression of prostate cancer to its most lethal castrate resistant form, but also impact design strategies for novel therapeutic interventions that will have the greatest implications in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This study was in part supported by the Department of Defense-PC040800 (L.E.) and the National Cancer Institute- P50 CA58236 (R.P.). The Institute Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) approved all mouse protocols used in this study. We would also like to thank the histology department at RPCI for assistance with our IHC staining.

Footnotes

Authors' contributions: LE performed research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. KL performed research. SR analyzed data. RA performed research. RP analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Pienta KJ, Abate-Shen C, Agus DB, Attar RM, Chung LW, Greenberg NM, Hahn WC, Isaacs JT, Navone NM, Peehl DM, Simons JW, Solit DB, Soule HR, VanDyke TA, Weber MJ, Wu L, Vessella RL. The current state of preclinical prostate cancer animal models. Prostate. 2008;68(6):629–639. doi: 10.1002/pros.20726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang S, Gao J, Lei Q, Rozengurt N, Pritchard C, Jiao J, Thomas GV, Li G, Roy-Burman P, Nelson PS, Liu X, Wu H. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(3):209–221. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellwood-Yen K, Graeber TG, Wongvipat J, Iruela-Arispe ML, Zhang J, Matusik R, Thomas GV, Sawyers CL. Myc-driven murine prostate cancer shares molecular features with human prostate tumors. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(3):223–238. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiao J, Wang S, Qiao R, Vivanco I, Watson PA, Sawyers CL, Wu H. Murine cell lines derived from Pten null prostate cancer show the critical role of PTEN in hormone refractory prostate cancer development. Cancer Res. 2007;67(13):6083–6091. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson PA, Ellwood-Yen K, King JC, Wongvipat J, Lebeau MM, Sawyers CL. Context-dependent hormone-refractory progression revealed through characterization of a novel murine prostate cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 2005;65(24):11565–11571. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis L, Bots M, Lindemann RK, Bolden JE, Newbold A, Cluse LA, Scott CL, Strasser A, Atadja P, Lowe SW, Johnstone RW. The histone deacetylase inhibitors LAQ824 and LBH589 do not require death receptor signaling or a functional apoptosome to mediate tumor cell death or therapeutic efficacy. Blood. 2009;114(2):380–393. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-182758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindemann RK, Newbold A, Whitecross KF, Cluse LA, Frew AJ, Ellis L, Williams S, Wiegmans AP, Dear AE, Scott CL, Pellegrini M, Wei A, Richon VM, Marks PA, Lowe SW, Smyth MJ, Johnstone RW. Analysis of the apoptotic and therapeutic activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors by using a mouse model of B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(19):8071–8076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702294104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao CP, Liang M, Cohen MB, Flesken-Nikitin A, Jeong JH, Nikitin AY, Roy-Burman P. Mouse prostate cancer cell lines established from primary and post-castration recurrent tumors. Horm Cancer. 2010;1(1):44–54. doi: 10.1007/s12672-009-0005-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scher HI, Sawyers CL. Biology of progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: Directed therapies targeting the androgen-receptor signaling axis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(32):8253–8261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, Rosenfeld MG, Sawyers CL. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, Chen Y, Watson PA, Arora V, Wongvipat J, Smith-Jones PM, Yoo D, Kwon A, Wasielewska T, Welsbie D, Chen CD, Higano CS, Beer TM, Hung DT, Scher HI, Jung ME, Sawyers CL. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324(5928):787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]