Abstract

Homo-oligomeric protein assemblies are known to participate in dynamic association/disassociation equilibria under native conditions, thus creating an equilibrium of assembly states. Such quaternary structure equilibria may be influenced in a physiologically significant manner either by covalent modification or by the non-covalent binding of ligands. This review follows the evolution of ideas about homo-oligomeric equilibria through the 20th and into the 21st centuries and the relationship of these equilibria to allosteric regulation by the non-covalent binding of ligands. A dynamic quaternary structure equilibria is described where the dissociated state can have alternate conformations that cannot reassociate to the original multimer; the alternate conformations dictate assembly to functionally distinct alternate multimers of finite stoichiometry. The functional distinction between different assemblies provides a mechanism for allostery. The requirement for dissociation distinguishes this morpheein model of allosteric regulation from the classical MWC concerted and KNF sequential models. These models are described alongside earlier dissociating allosteric models. The identification of proteins that exist as an equilibrium of diverse native quaternary structure assemblies has the potential to define new targets for allosteric modulation with significant consequences for further understanding and/or controlling protein structure and function. Thus, a rationale for identifying proteins that may use the morpheein model of allostery is presented and a selection of proteins for which published data suggests this mechanism may be operative are listed.

Keywords: Allostery, protein multimer, morpheein, moonlighting

Introduction

Modern biophysical methods yield an enhanced appreciation of protein dynamics and the vital role these dynamics play in biochemical processes [1–4]. This commentary focuses on quaternary structure dynamics and strives to provide a historical perspective on the evolution of concepts and hypotheses related to quaternary structure equilibria in relation to allosteric control of protein function. It includes a historical review of protein structure dynamics, leading up to and beyond the introduction of the concept of allostery by Monod and coworkers [5, 6]. Previously established and proposed models of allostery are presented with an emphasis on the role of subunit dissociation in the allosteric process. In particular, consideration is given to the functional control of homo-oligomeric proteins that can dissociate and potentially rearrange, reversibly, under native conditions. Only proteins that change quaternary structure without covalent modification and whose quaternary structure equilibria respond to ligand binding are considered. For clarity, a glossary of important terms used in this review is included (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions of Terms Used.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Conformational change | A change in secondary or tertiary structure that is distinct from any small structural variations in protein structure and any dynamic conformational equilibria that are widely appreciated as essential to protein function |

| Dissociation/association | While there are conditions where virtually any protein can be made to change its quaternary structure, for the purposes of this review dissociation/association refers only to a change in oligomeric state under physiologically relevant native conditions |

| Dynamic equilibria | A protein in dynamic equilbria describes a situation in which all of the conformational states of the protein are readily accessible such that binding of ligand stabilizes a conformation |

| Induced fit | Induced fit will be used to describe a situation where binding of a ligand to a low affinity site induces a conformational change in the protein that is not accessible in the absence of ligand binding. The induced conformation of the protein has a high affinity for the ligand |

| Morpheein | A homo-oligomeric protein that exists as an ensemble of quaternary structural forms with different functionality. The defining characteristic is that interconversion between higher order multimers requires a mandatory dissociation to a lower order multimer and a conformational change in the lower order state prior to assembly to the alternate higher order multimer. |

Special emphasis is given to homo-oligomeric proteins that can reversibly come apart and change conformation in the dissociated state. The altered conformation of the dissociated state may then reassemble to a structurally and functionally distinct oligomer as illustrated in Figure 1 (a and b). We have called such proteins morpheeins and the individual oligomeric assemblies are called alternate morpheein forms [7, 8]. The unique and defining characteristics of morpheeins are 1) that different assemblies have different functions and 2) that the interchange of morpheein forms requires dissociation of higher order oligomers to allow conformational change in the dissociated state. The prototype morpheein is the enzyme porphobilinogen synthase, whose quaternary structure equilibrium includes a high activity octamer, a low activity hexamer, and a dimer whose conformation dictates assembly to one or another higher order oligomer (Figure 1c). The identification of proteins that can undergo reversible quaternary structure rearrangements has the potential to define new allosteric targets for the modulation of biologic activity with significant consequence for human health and disease. This article provides suggestions for the identification of proteins whose functional control may involve an equilibrium of morpheein forms. Based predominantly on the literature a large number of putative morpheeins, most of which remain to be verified experimentally, are listed in Table 2 along with their characteristics that are consistent with but not confirmatory that the protein is a morpheein.

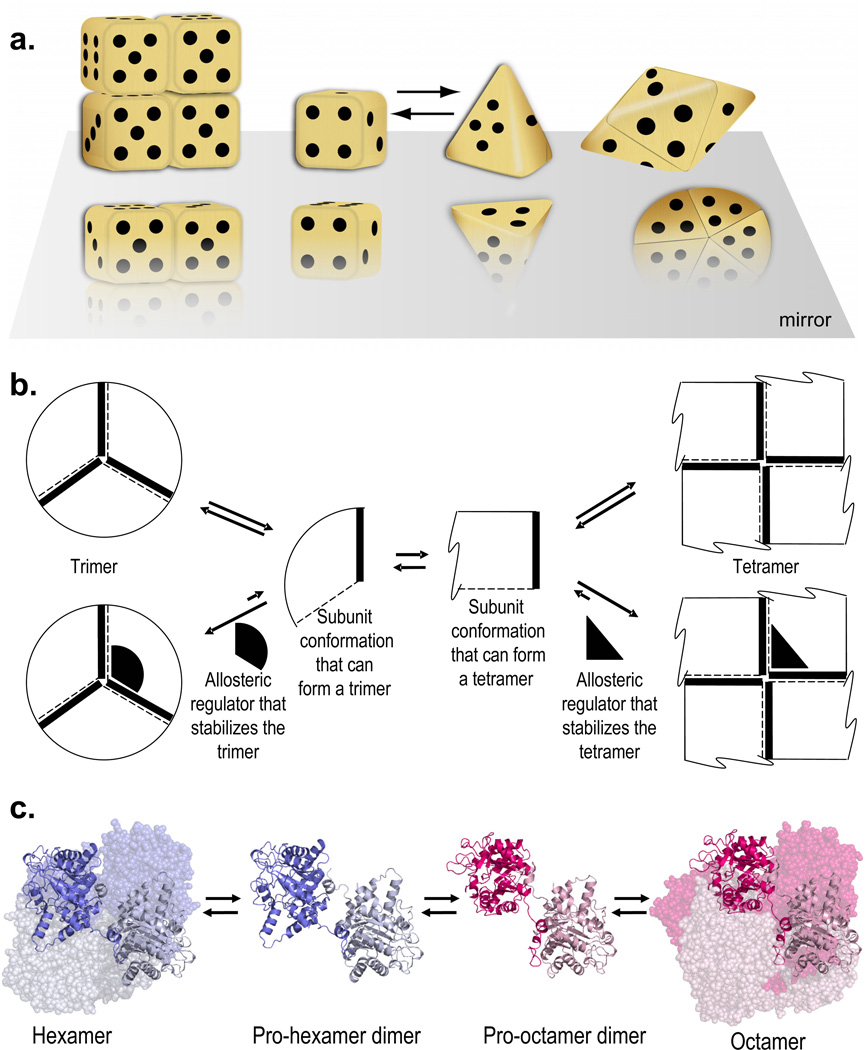

Figure 1. The morpheein model of allostery.

The quaternary structure dynamic characteristic of morpheeins includes the interchange of alternate oligomers mediated by a conformational change in the dissociated state. The required conformational change involves a limited number of backbone changes such that some domain surfaces remain unchanged. The required conformational changes do not reflect a major unfolding or refolding event. a) A three dimensional morphing dice model is illustrated. Oligomer assembly associates a die face with one dot with a die face with four dots such that a six-sided cubic die assembles to a tetramer while a four-sided pyramidal die assembles to a pentamer. The cubes-to-pyramids conformational change involves the coming together of 5-dot surfaces with 6-dot surfaces in each individual subunit. Such a conformational change likely reflects the reorientation of individual domains of each subunit by rotation around a hinge. In the morpheein model, this change must occur in the dissociated state; it cannot occur while the subunit is in either of the higher order multimers. b) A two dimensional geometric illustration includes a representation of the effect of allosteric regulators on the position of the equilibrium. The conformational change in the dissociated state is the interconversion of a pie wedge and a rectangle. Oligomer assembly associates the dashed lines with the solid lines such that the pie wedge assembles into a trimer and the rectangle assembles into a tetramer. Allosteric effectors (solid black shapes) that are suited to bind to components of either the trimer or the tetramer are shown to draw the equilibrium in the direction of the ligand-bound oligomer. c) The PBGS quaternary structure equilibrium. A low activity hexamer does not have subunit interactions necessary for an ordered active site lid. Dissociation to the pro-hexamer dimer can be followed by a conformational change that reorients the two αβ-barrel domains to form the pro-octamer dimer. Association to the octamer occurs forming subunit interfaces that support order in the active site lid [33].

Table 2.

Proteins with characteristics consistent with a morpheein model of allosteric regulation

| Protein | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase-1 Gallus Domesticus E.C. 6.4.1.2 CAS 9023-93-2 |

This is a multifunctional protein that exists in equilibrium between active and inactive dimers with active dimers in equilibrium with larger oligomers [108]. The equilibria are allosterically controlled. An inhibitor of the biotin carboxylase domain functions by impairing oligomerization [109]. |

| α-Acetylgalactosaminidase Bos taurus E.C. 4.3.2.2 CAS 9027-81-0 |

The activity is protein concentration dependent [110]. There are active tetramers and inactive monomers with substrate turnover favoring the tetramer [111]. By implication, there is one subunit conformation that does not bind substrate and cannot oligomerize and one that does bind substrate and can associate to tetramer. |

| Adenylosuccinate lyase Bacillus subtilis E.C. 4.3.2.2 CAS 9027-81-0 |

Tetramer dissociation produces monomer, dimer, trimer, tetramer mixture [112]. Various mutations produce trimers with smaller forms. The tetramer has high a Vmax and a low Km, while all other forms have low Vmax and high Km values. In the tetramer each active site is comprised of elements of three subunits. Removal of one subunit does not result in the retention of one competent active site suggesting major structural rearrangements that compromise all remaining active sites. Secondary structural changes parallel changes in quaternary structure and activity [113]. |

| Aristolochene synthase Penicillium requeforti E.C. 4.2.3.9 CAS 94185-89-4 |

SEC elution profiles are variable showing monomer and larger species [114]. Activity is lost at higher protein concentration [115]. |

| L-Asparaginase Leptosphaeria michotii E.C. 3.5.1.1 CAS 9015-68-3 |

The protein is observed as a dimer, tetramer and inactive octamer. The rate-limiting step of catalysis was related to enzyme structural changes [116]. Type I asparaginase, shows an allosteric reorganization of the tetramer upon binding asparagines [117]. |

| Aspartokinase Escherichia coli E.C. 2.7.2.4 & 1.1.1.3 CAS 9012-50-4 |

Isoforms I and II are bifunctional having both aspartokinase and homoserine dehyrogenase activities. Isoform I has been shown to be a dissociating enzyme [118]. In a refolding study, the monomer was shown to have only aspartokinase activity. The dimer had apartokinase and homoserine dehydrogenase activity and the dehydrogenase activity was allosterically controlled. In the tetramer, both activities are present and are both allosterically controlled [119]. Isoform III is mono-functional but exists in dimer tetramer equilibrium with different subunit conformations in the two quaternary structural forms [120]. |

| ATPase of the ABCA1 transporter Homo sapiens E.C. 3.6.1.3 CAS 9000-83-3 |

Exists in equilibrium between dimers and functional tetramers. The binding of ATP favors tetramers [121]. |

| Biotin holoenzyme synthetase Escherichia coli E.C. 6.3.4.15 CAS 37340-95-7 |

A monomer-dimer equilibrium has been characterized. The monomer functions as a ligase while the dimer functions as a repressor of the biotin biosynthesis operon [122]. There is no evidence for monomer binding to DNA [123] suggesting that one conformation of the monomer functions as ligase and another dimerizes to form the repressor. Biotinyl-5’-adenylate allosterically regulates dimer formation. |

| Chorismate mutase Escherichia coli E.C. 5.4.99.5 CAS 9068-30-8 |

The WT enzyme is a dimer but variants exist as monomers, hexamers and as a trimer-hexamer equilibrium. The trimer and hexamer apprear to be structurally similar but the dimer is structurally distinct [124]. |

| Citrate synthase Escherichia coli E.C. 2.3.3.1 CAS 9027-96-7 |

Monomer, dimer, trimer, tetramer, pentamer, hexamer and dodecamer forms have been identified [125]. The E. coli enzyme exists in a dimer-hexamer equilibrium that is pH and protein concentration dependent and NADH binds strongly to the hexamer and draws the equilibrium away from the dimer. |

| Cyanovirin-N Nostoc ellipsosporum CAS 918555-82-5 |

A cyanobacterial lectin whose structures reveal a tightly packed monomer [126] and a domain-swapped dimer [127] comprised of monomers with a more open structure. The monomer and dimer exist in equilibrium in solution along with a small amount of higher order aggregates [128, 129]. Thus there appears to be a tightly packed monomer conformation that cannot oligomerize and a looser monomer conformation that can oligomerize. |

| Coenzyme A transferase Sus scrofa domestica E.C. 2.8.3.5 CAS 9027-43-4 |

The protein has been characterized as a dimer and a tetramer which are separated by a ‘large kinetic barrier’ [130]. The oligomers are chromatographically separable and physiologically relevant [130]. The homodimer and homotetramer are reported to be catalytically indistinguishable, which raises the question of whether or not addition of substrate preferentially stabilizes one of the forms [81]. |

| Cystathionine β-synthase Homo sapiens E.C. 4.2.1.22 CAS 9023-99-8 |

The enzyme exists in an equilibrium of multiple oligomeric states ranging from dimer to a 16-mer [131]. Removal of the C-terminal regulatory domain produces dimers [132] suggesting that higher order oligomerization depends on the conformation of this domain. The dimer is the high activity form of the enzyme and is allosterically favored by binding of the effector AdoMet to the regulatory domain. Thus AdoMet favors a dimer conformation that cannot oligomerize while in the absence of AdoMet other dimer conformations may dictate assembly to the various oligomerization states that have been observed. Experts on the enzyme have suggested that it may be a morpheein [133]. Many disease causing mutations are found distant from the active site [134]. |

| d-Amino acid oxidase E.C. 1.4.3.3 CAS 9000-88-8 |

Exists as an equilibrium of monomers, dimers and higher order polymers that is dependent on temperature. A break in an Arrhenius plot is associated with change in quaternary structure that changes functionality [135, 136]. |

| Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase Sus scrofa domestica E.C. EC 1.8.1.4 CAS 9001-18-7 |

Exists in an equilibrium of tetramer, dimer, and monomer that is pH dependent. It has been reported to function as a dehydrogenase, a diaphorase and a protease. The dehydrogenase activity is associated with dimer and tetramer, the diaphorase activity is reported for all three oligomeric states and the protease activity is found in the monomer only [137]. Two forms of the dimer have been reported[138, 139] and conformational changes have been observed upon dissociation to monomer [140]. |

| Dopamine β-monooxygenase Bos Taurus E.C. 1.14.17.1 CAS 9013-38-1 |

This enzyme has been reported to exist in an equilibrium between dimers and tetramers. The two forms display different Km values with the dimer being the low Km form. Ascorbate, fumarate and chloride ions are allosteric effectors [141–143]. |

| Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase Homo sapiens E.C. 2.5.1.29 CAS 9032-58-0 |

Similar to PBGS this enzyme has been characterized as an octamer [144], a hexamer [145] and as a mixture of the two quaternary structural forms [146]. |

| GDP-mannose dehydrogenase Pseudomonas aeruginosa E.C. 1.1.1.132 CAS 37250-63-8 |

This enzyme displays complex kinetic behavior [95] that is characterized by enzyme concentration dependent specific activity. The specific activity is also dependent on the order of addition of reaction components. Assays initiated by the addition of substrate show marked hysteresis. Sizing studies indicate a trimer-hexamer equilibrium [147] while a crystal structure shows tetramer [148]. There may be a low activity tetramer and a high activity hexamer, which differ in the orientation of subunit domains such as to accommodate different quaternary structures. |

| Glutamate dehydrogenase Bos taurus E.C. 1.4.1.2 CAS 9001-46-1 |

An inactive hexamer has been characterized to be in equilibrium with polymeric forms with molecular weights of up to 2 × 106 Da [149]. This suggests that at minimum there must be an inactive conformation of the hexamer that cannot polymerize and an active conformation of the hexamer that can polymerize. GDP and GTP are allosteric inhibitors [150] and appear to stabilize the inactive hexamer. |

| Glutamate racemase Mycobacterium tuberculosis Escherichia coli Bacillus subtilis Aquifex pyrophilus E.C. 5.1.1.3 CAS 9024-08-02 |

Enzymes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis have been shown to moonlight as DNA gyrase inhibitors as well as racemases [151–153]. Alternate dimer structures have been crystallized [154–156] and a dimer-monomer equilibrium has been observed for the Bacillus subtilis enzyme [157]. For the Aquifex pyrophilus enzyme a monomer-dimer equilibrium was identified by SEC and a dimer-tetramer equilibrium was supported by dynamic light scattering [158]. |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Oryctolagus cuniculas Sus scrofa domestica E.C. 1.2.1.12 CAS 9001-50-7 |

An equilibrium between monomer, dimer, and tetramer has been characterized [159]. A myriad of moonlighting functions of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) such as endocytosis, microtubule bundling, phosphotransferase activity, translational regulation, nuclear export, DNA replication DNA repair have been reported [160]. Some of the functions of GAPDH are reported to be carried out by specific quaternary forms, for example, the monomeric form performs microtubule bundling but does not possess dehydrogenase activity [161]. |

| Glycerol kinase Escherichia coli E.C. 2.7.1.30 CAS 9030-66-4 |

This enzyme has been characterized as active dimer ⇔ active tetramer ⇔ inactive tetramer [162–164]. Fructose 1,6 bisphosphate (FPB) binds allosterically to the inactive tetramer. However, a system such as active tetramer ⇔ active dimer ⇔ inactive dimer ⇔ inactive tetramer may also explain the data. Favoring the latter model crystal structures of two different tetramers have been observed [165] in which the conformations of the dimers is slightly different. It has been suggested that FBP inhibits by preventing domain motion [166]. |

| HIV-Integrase Human immunodeficiency virus-1 E.C. 2.7.7.- CAS 52350-85-3 |

HIV-Integrase performs two functions; 3’ end processing and integration of the viral DNA in to the host DNA. It exists in equilibrium between monomer, dimer, tetramer and higher order states [167–169]. The dimer performs 3’ end processing [170] and tetramer performs the integration [169]. “Shiftides” that stabilize the dimer conformation prevent integration [92] suggesting that the subunits are in a different conformation in the tetramer. Thus the formation of at least the dimer and the tetramer may be dictated by the conformation of the monomer. |

| HPr-Kinase/phosphatase Bacillus subtilis Lactobacillus casei Mycoplasma pneumoniae Staphylococcus xylosus E.C. 2.7.1.-/3.1.3.- CAS 9026-43-1 |

This is bifunctional enzyme with kinase and phosphatase activity. It displays complex kinetics including cooperativity that varies with reaction conditions. The crystal structures of HPrK/P from Lactobacillus casei [171], Staphylococcus xylosus [172] and Mycoplasma p neumoniae [173] all show a hexameric assembly composed of two trimers. These structures show that nucleotide binding would likely require the protein to change its quaternary structure [174]. A detailed analysis of Bacillus subtilis enzyme suggests a pH-dependent structural equilibrium of monomers, dimers and hexamers [175]. Allosteric activators and substrates affect the equilibrium; the study concluded that the oligomerization state might be an important factor in the switch between kinase and phosphatase activity [175]. A fluorescence study also concluded that the B. subtilis enzyme exists as a heterogeneous population of oligomers [176]. |

| Lactate dehydrogenase Bacillus stearothermophilus E.C. 1.1.1.27 CAS 9001-60-9 |

There is an equilibrium between dimer and tetramer: the tetramer is favored by increased protein concentration and fructose 1,6 bisphosphate [177, 178]. The dimer has a high Km and the teramer has a low Km. A crystal structure of the dimer revealed that there are rearrangements that preclude formation of the tetramer suggesting that there is one conformation of the dimer that cannot oligomerize and one that can [179]. A single mutation at the allosteric site stabilizes the tetramer [180]. |

| Lon protease Escherichia coli Mycobacterium smematis E.C. 3.4.21.53 CAS 79818-35-2 |

The E. coli enzyme has multiple oligomeric forms, that are characterized by allostrey, hysteresis and enzyme concentration dependent activity [181]. The M. smegmartis enzyme, displays oligomeriztion that is induced by Mg2+ and/or substrate. Monomer, dimer, trimer and tetramer have been observed by SEC, and hexamer was observed by ultracentrifugation [182, 183]. |

| Mitochondrial NAD(P)+ Malic enzyme Homo sapiens E.C. 1.1.1.40 CAS 9028-47-1 |

Mutations distant from the active site cause changes in aggregation state and activity [184]. The major oligomeric forms are dimers and tetramers with some monomer present. The tetramer appears to be the fully functional form and is a dimer of dimers. The allosteric activator fumarate binds at the dimer interface [185] and thus may activate by influencing an equilibrium between a dimer that cannot bind fumarate or tetra,merize and a dimer that can bind fumarate and dictates assembly to the active tetramer. Similarly, NAD(P)+ malic enzymes in plants that function in the chloroplast or the cytosol undergo changes in oligomerization and exhibit hysteresis [186]. |

| Peroxiredoxins Salmonella typhimurium E.C. 1.6.4.-1.11.1.15 207137-51-7 |

These enzymes appear to exist in an equilibrium of dimeric and decameric forms, which for some peroxiredoxins is redox sensitive [187]. Poole [188] has modeled an alternative form of the crystallographic dimer, a form that should better support catalysis, and this form cannot oligomerize to the decamer. Sedimentation velocity results for the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase of Salmonella typhimurium are dependent both on protein concentration and oxidation state. In the oxidized form of the protein, an obligate dimer is in equilibrium with a donut-shaped decamer and an increase in the concentration of the protein favors formation of the decamer [187]. The data are consistent with the dimer existing in two alternative conformations, one that can oligomerize to the decamer and one that cannot [188]. Peroredoxin have been suggested to be morpheeins [189]. |

| Phenylalanine hydroxylase Homo sapiens E.C. 1.14.16.1 CAS 9029-73-6 |

The data are consistent with an equilibrium between high activity tetramer and low activity tetramer that is mediated by dissociation to dimer. The wild type enzyme displays a mixture of dimers and tetramers plus some higher order oligomers upon gel filtration chromatography [190]. The substrate, L-phenylalanine, is an allosteric activator and incubation of isolated dimer with the substrate favors tetramer [191, 192]. The low activity tetramer was observed for the T427P variant which exists in equilibrium between the low activity dimer and the low activity tetramer [192]. Residue 427 lies in a flexible hinge region in the tetramerization domain that allows domain swapping at the C-terminal to form the tetramer [193]. Spectroscopic changes upon activation are observed due to conformational changes [194]. |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase Escherichia coli Zea mays E.C. 4.1.1.31 CAS 9067-77-0 |

Inactive dimer and active tetramer have been shown to be in equilibrium that is influenced by allosteric effectors. The transition between forms is slow enough to produce hysteresis in kinetics [195]. Crystal structures of the allosterically inactivated E. coli enzyme and active Zea mays enzyme are both dimers of dimers but the orientation of the subunits to each other in the two dimers is different [196]. It appears that the enzyme may dissociate to dimers to allow realignment of the subunits. Thus at minimum the enzyme may exist as an active tetramer, a dimer with subunits oriented as in the active tetramer and an inactive dimer in which the orientation of the subunits differs from that in the other dimer. |

| Phosphofructokinase Bacillus stearothermophilus Thermus thermophilus E.C. 2.7.1.11 CAS 9001-80-3 |

Interchanage of inactive dimers and active tetramers has been demonstrated for the Bacillus stearothermophilus enzyme [197]. The enzyme is allosterically inhibited by phosphenolpyruvate (PEP) and allosterically activated by ADP. Formation of tetramers from dimers is a double exponential process which may reflect changes from a dimer that cannot oligomerize but binds PEP to a dimer that can oligomerize and binds ADP and the association of the dimer. Similarly, the Thermus thermophilus enzyme has been shown to exist in a tetramer-dimer equilibrium that is modulated by allosteric effectors [198]. |

| Polyphenol oxidase Agaricus bisporus Malus domestica Lactuca sativa L. E.C. 1.10.3.1 CAS 9002-10-2 |

The Agaricus bisporus enzyme exists as monomer, trimer, tetramer, octamer and dodecamer and these forms are able to interconvert [199, 200]. The enzyme possess cresolase and catecholase activities and the ratios of these activities depends on the method of purification [201]. The Malus domestica chloroplast enzyme exists in at least three interconverting aggregation states as measured by activity [202]. Although not ascribed to by the authors the hysteretic kinetic behavior of the Lactuca sativa L. enzyme may also be the result of a change in the aggregation state to produce a more active enzyme following the addition of substrate [203]. |

| Purine nucleoside phosphorylase Bos Taurus Escherichia coli E.C. 2.4.2.1 CAS 9030-21-1 |

The enzyme has a variety of oligomeric stoichiometries [204]. Crystal structures show both trimers [205] and hexamers; the arrangement of subunits in the calf spleen PNP trimer [206], which is reported as half of a hexamer, is different from the arrangement of Escherichia coli PNP subunits, which is a hexamer consisting of three dimers. There are many examples non-traditional-Michaelis-Menten kinetics consistent with high and low Km forms [204, 207, 208]. |

| Pyruvate kinase Homo sapiens E.C. 2.7.1.40 CAS 9001-59-6 |

The reported forms in one study are an active tetramer, an active dimer and an inactive dimer [209]. The inactive dimer does not associate while the active dimer is able to associate to tetramer. Dimers are able to interconvert. Ibsen et al. found monomers, dimers, trimers, tetramers and pentamers [210]. |

| Ribonuclease A Bos taurus E.C. 3.1.27.5 CAS 9901-99-4 |

Multiple oligomers are formed via domain swapping at both the N- and C-termini [211]. Monomers, dimers, trimers, tetramers, pentamers, hexamers and higher order oligomers have been identified and each multimeric form appears to have at least two conformations [212–215]. Different functionalities are associated with the different oligomerization states [216–218]. |

| Ribonucleotide reductase Mus musculus E.C. 1.17.4.1 CAS 9047-64-7 |

A model for the allosteric regulation of mammalian ribonucleotide reductase (based on studies of the Mus musculus enzyme) involves two different structures for the subunit, one that can assemble into a hexamer and one that can assemble into a tetramer [219, 220]. There is a crystal structure for the homologous E. coli ribonucleotide reductase, which shows a hexameric assembly [221], but a crystal structure does not yet exist for a tetrameric assembly. More recently a crystal structure for the human hexamer has appeared [222]. |

| S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase Dictyostelium discoideum E.C. 3.3.1.1 CAS 9025-54-1 |

The active form of the enzyme from Dictyostelium discoideum is a tetramer that is favored by the binding of NAD+ [223]. The enzyme is inactivated in the presence of cAMP. In the absence of NAD+ a mixture of dissociated forms is observed by native PAGE. Multiple oligomeric states have also been observed for the enzyme from Lupinus luteus [224] and Rattus norvegicus [225]. |

| Biodegrative threonine dehydratase (threonine deaminase) Escherichia coli E.C. 4.3.1.19 CAS 774231-81-1 |

The enzyme has been characterized as an active tetramer that is equilibrium with inactive monomer [226, 227]. AMP is an allosteric activator that promotes tetramer formation. There is also evidence for a low activity tetramer-inactive monomer equilibrium and binding of AMP to a monomer form [228]. The data appear consistent with; active tetramer that can bind AMP ⇔ monomer that can bind AMP ⇔ monomer that cannot bind AMP ⇔ low activity tetramer that cannot bind AMP. |

| Tryptase-β Homo sapiens E.C. 3.4.21.59 CAS 97501-93-4 |

The quaternary structural forms of β-tryptase are an active tetramer, an active monomer, an inactive monomer and an inactive tetramer [229–238]. Morpheein character is suggested by a high performance size exclusion chromatography study which showed that upon diluting β-tryptase from conditions that stabilized the active tetramer to those approximating physiological there was a rapid dissociation to monomer followed by a slow formation of tetramer [239]. The re-association to tetramer is consistent with two monomer conformations. |

| Tumor necrosis factor α Homo sapiens CAS 94948-61-5 |

The quaternary structural forms exist in a solution equilibrium of monomers, dimers, and trimers [240, 241]. The active form of TNFα is a globular trimer and the interconversion between monomers and trimers involves the accumulation of dimers [242]. |

| Uracil phosphoribosyl-transferase Esherichia Coli E.C. 2.4.2.9 CAS 9030-24-4 |

Non-additive quaternary structures have been observed. Sedimentation and gel filtration analyses suggest a trimer-pentamer equilibrium [243]. The pentamer is active and the trimer is not. Allosteri activation by GTP and substrate activation both favor the pentamer. |

A Historical Perspective – One Hundred Years of Thought on Quaternary Structure Dynamics and the Control of Protein Function

Early studies of hemoglobin

Starting in 1904, when Bohr discovered the cooperative binding of oxygen to hemoglobin [9], the behavior of hemoglobin became the inspiration for hypotheses about how protein subunits communicate. Bohr’s sigmoidal curve for oxygen binding to hemoglobin suggested that the binding of one oxygen molecule increased the affinity for another. Quantification of oxygen binding to hemoglobin by Hill in 1910 was based on the premise that hemoglobin was a heterogeneous system of oligomers of different stoichiometry [10, 11]. Hill’s equation (Eqn. 1) described the sigmoidal oxygen binding curve.

| Eqn. 1 |

The term n represents the average stoichiometry of the oligomers; y represents the percentage saturation with O2; K is the equilibrium constant for O2 binding; and × is the O2 partial pressure. The Hill equation is valid regardless of whether the alternate oligomers are in equilibrium or if they constitute a simple non-equilibrating mixture. Hill’s “cooperativity factor” n, now known as the Hill coefficient, is most often currently interpreted to define the cooperativity that exists between subunits of a non-dissociating oligomer of fixed stoichiometry. However, the view of hemoglobin as a mixture or equilibrium of oligomers remained popular for two decades [12–17].

In 1925 the pendulum swung towards a more homogeneous view of the oligomerization state of hemoglobin when Adair determined that hemoglobin was predominantly a tetramer [18]. The sigmoidal behavior was then interpreted as O2 binding to subunits of the tetramer progressively increasing the affinity of the unoccupied site(s) for O2. The homogeneous tetramer model promoted a view of hemoglobin as a protein whose function did not require dissociation. In 1936 Pauling proposed a similar model in which the heme groups were arranged in a square and that binding of O2 at one corner of the square would assist binding at adjacent corners [19]. Regardless of the details of the early models of hemoglobin function, to this day hemoglobin function is generally considered in terms of a tetrameric structure for which dissociation is not physiologically relevant [20]. With the exception of Lamprey hemoglobin, which is known to form monomers when carrying oxygen [21], there is little evidence to refute the stable tetrameric view of hemoglobin, particularly in light of the high concentration of hemoglobin in blood.

Although the function of hemoglobin was integral to the development of ideas about subunit communication (and allosteric regulation), the behavior of hemoglobin need not represent the behavior of all oligomeric allosteric proteins. Consider that hemoglobin was long believed to be a homo-oligomer, made up of one kind of subunit. It wasn’t until 1959, more than fifty years after Bohr’s first observations, that hemoglobin was established to be comprised of two different protein chains [22]. These details about the molecular heterogeneity of tetrameric hemoglobin are often downplayed when describing hemoglobin as the quintessential model for cooperativity and/or allostery. For simplicity, with the exception of hemoglobin, the focus of this review is on homo-oligomeric proteins containing subunits with one primary amino acid sequence.

Quaternary structure

The studies of Svedberg (1912–1940) [23–27] suggested that many proteins are comprised of subunits. Nevertheless, Linderstrom-Lang and Schellman’s classic 1959 chapter entitled “Protein Structure and Enzyme Activity,” [28] discusses only primary, secondary, and tertiary structure. The chapter addresses molecular dynamics, but does not mention quaternary structure in either a static nor a dynamic sense. More than ten years later, in a comprehensive review of protein quaternary structure by Klotz et al., [29] the inherent symmetry of homo-oligomeric proteins is introduced with an appreciation that “all subunits in an oligomeric protein are in equivalent (or pseudo identical) environments” and that all of the interacting interfaces are saturated (or involved in a subunit interaction). This dictates that the geometries must be closed, such that if a “protein is composed of four subunits their final arrangement should be such as to make the formation of a hexamer or octamer unlikely”. When dissociation is suggested, it is uniformly seen as additive (two hexamers associating to make a dodecamer; or two tetramers associating to make an octamer). The state-of-the-art in 1970 did not consider that there might be a dissociated state with different conformations that have distinct oligomerization properties; it had not been seen and was not imagined. This additive view of homo-oligomerization has remained the common view and is implied in the most modern of works on protein subunit assembly [30–32]. Thus the observation of an equilibrium of the non-additive alternate oligomers of porphobilinogen synthase as illustrated in Figure 1c and described in an accompanying article [33], was surprising, but it need not be unique [34].

Protein dynamics

Separate from hypotheses about communication between subunits of protein oligomers was the evolution of general notions about protein structure dynamics. The history of this intellectual inquiry is described from the time it was established that the chemical structure of a protein is a linear polypeptide chain and when it was generally accepted that each protein had a fixed amino acid sequence (circa 1940). Words like conformation and configuration as used in mid-twentieth century publications predated our current understanding of the protein folding process or of concepts such as a particular protein fold (e.g. the αβ-barrel). The evolution of language in a relatively rapidly changing field yields a lack of clarity as to whether the envisioned alternate configurations mentioned in mid twentieth century documents were meant to represent what are now called different protein folds (big changes), different side chain rotomer conformations (small changes), or the diverse continuum between. Early notions on the structure of proteins, particularly antibodies, included the hypothesis that at least some protein sequences can exist in many configurations with nearly the same energy [35, 36]. This hypothesis was put forth to explain how a relatively small number of antibodies could protect against the much greater number of antigens. Notable early contributions to a dynamic view of protein structure were from Linderstrom-Lang and coworkers [28]. However, during the 1950’s and 1960’s when much effort was directed at determining the one correct sequence of several proteins (e.g.) [37] and protein crystallography generated the first protein crystal structures [38, 39], the dynamic view of protein structure was undersold in favor of a more rigid view of a single, most stable conformation for a given protein sequence. The appearance of protein crystal structures, which by their very nature provide a snapshot of a single conformation of a protein, fueled static views and the bulk of the current literature continues to interpret data in terms of a single native state. Deviations from this state are often referred to as partially unfolded or misfolded. The field continues to struggle to consistently consider an equilibrium ensemble of native states as has been put forth in the concept of proteostatis [40], a modern concept that does not yet address quaternary structure dynamics.

Historical models for ligand binding also reflect the static views that derived from the first few decades of protein crystal structure determination. The lock and key hypothesis [41] illustrates a ligand binding to a rigid protein structure. The related induced fit hypothesis [42], which promoted a view of at least two distinct protein conformations, did not address alterations in terms of quaternary structure dynamics. Even by 1979, twenty years after the first solution of an X-ray crystal structure of a protein, there were crystal structures of only about fifty protein molecules [38]. Thus, although small fluctuations in protein structure were generally understood to occur, the notion of relatively fixed protein structures was generally accepted by the mid 1960’s when the classic theories of allosteric regulation of protein function were first introduced (see below).

There is an intrinsic relationship between stable protein assembly states and the probability of obtaining protein crystals that diffract to a high atomic resolution. Because the existence of a dynamic equilibrium of quaternary structure assemblies is predicted to be detrimental to the solution of a protein crystal structure, the Protein Structure Initiative avoided proteins that chromatographed as multiple peaks on a size exclusion column and focused on proteins whose size appears to be more uniform. Up until about a decade ago the Protein Data Bank provided little information on the quaternary structure of the biologically relevant assembly. Now the Protein Data Bank and related online services such as PISA, PQS, and ProtBuD provide considerable analysis of potential quaternary structure assemblies [43–45]. Although determination of protein domain flexibility is a strength of NMR protein structure determination, molecular size limitations have largely prevented NMR determined structures from addressing quaternary structure. Nevertheless, Gronenborn and coworkers have recently seen evidence for alternate quaternary structure assemblies using the NMR method [46–48].

As crystal structures began to appear, other studies were emerging that supported the rigid protein view. Based on work started in the 1950’s [49], Anfinsen and coworkers had established by the early 1970’s that protein sequence alone can provide all the information necessary to specify the native three-dimensional structure of at least some proteins [50, 51]. Implicit in Anfinsen’s principle is the assumption that there is only one physiologically relevant native structure, and presumably one native quaternary assembly. Despite Anfinson’s demonstration that denatured ribonuclease refolded to only one structure [50, 51], not all proteins were found to be so well behaved. The molecular chaperones later (1980s and beyond) found to assist protein folding had not yet been described. Thus, in the late 1960’s several groups considered metastable structural states. Nickerson and Day proposed metastable structures of a given protein with alternate functions [52]. Epstein and Schechter considered the possibility of “conformational isozymes” as one protein with more than one structure, each structure having different kinetic properties [53]. Recently revealed interdomain chain swapping is one example of such a conformational variant whose physiologic significance has yet to be addressed [54]. Leventhal considered the problem of multiple structures for one protein in the context of computational structure prediction [55]. These, and related papers on multistable proteins [56], protein conformers [57], and conformational isomers [58] were largely overlooked in favor of a one amino acid sequence, one structure paradigm. Conformational drift, introduced by Weber in 1986 to describe the slow recovery of homo-oligomeric proteins following high pressure treatment [59], was the first consideration of alternate oligomers in equilibrium through alternate conformations of a dissociated state (two different dimers interconverting through alternate monomer conformations). The recent NMR studies of Gronenborn and coworkers have indeed revealed alternate quaternary structure assemblies for what was originally considered a small monomeric protein [46]. The potential for physiologically relevant interchange of these forms is not yet documented.

The overwhelming data in favor of a dynamic protein structure is reflected by the “new view” of protein dynamics [60] in which proteins exist as an ensemble of conformations. Concepts such as conformational diversity [3] and intrinsically disordered (or naturally unfolded) proteins [2, 4, 61] are now readily accepted. Intrinsically disordered proteins which are thought to be unfolded in the absence of a ligand template are a prime example of the dynamics of proteins in solution.

The evolution of models for allostery

The focus of this section is to discuss the evolution of allostery in the context of the evolving views of protein quaternary structure dynamics. While it is not a requirement, most allosteric proteins are oligomeric and the significance of their dissociation/association to allosteric control is a focus of this review. Key observations revealing allostery were made in the 1950’s; metabolic products, chemically distinct from an enzyme substrate, were found to modulate enzyme activity [62, 63]. Thus arose the idea that protein function could be governed by binding of a ligand at a site other than the active site, and that such functional control could be physiologically significant [62, 64–66]. In 1963 the word allostery was introduced to describe the modulation of enzyme activity by effector molecules that were not sterically analogous to the substrate [6]. Monod and coworkers considered the complication of dissociating oligomers in the formulation of their model of allostery [32] and the 1965 introduction of the MWC concerted model for allostery explicitly made the simplifying assumption that the two distinct allosteric states of the protein (R and T) had the same fixed quaternary structure (e.g. both were tetrameric [5]). This assumption rapidly became an established view of allosteric oligomers, which has been perpetuated in texts for decades. In the concerted or “two state” model (Figure 2a) there are two conformations of the subunits. To maintain symmetry, all four subunits transform concertedly from one conformation to another. Both conformations were postulated to be accessible in the absence of allosteric effectors; with effectors stabilizing one form over the other. In this model, subunit dissociation was not considered essential to the interconversion between states. The KNF sequential model of allostery, introduced by Koshland, Nemanthy, and Filmer continued the assumption of a fixed oligomer [67]. The sequential model (Figure 2b) proposed that individual subunits in the oligomer were able to change conformation independent of their partner subunits. In this case the conformational change was mediated by an induced fit of the ligand. The introduction of the classic MWC or KNF model downplayed the possibility that quaternary structure assembly could be a dynamic component of the allosteric phenomenon. Oligomer dissociation was not promoted as part of the equation.

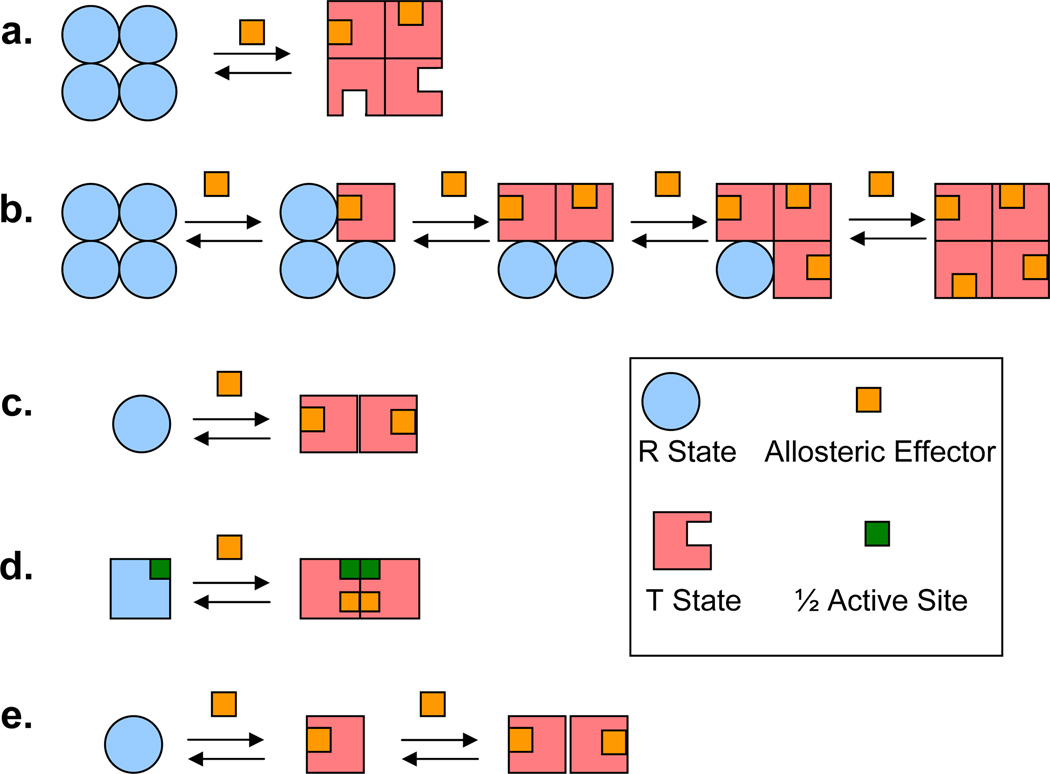

Figure 2. Models of allostery.

(a) The concerted model of Monod-Wyman-Changeux [5]. (b) The sequential model of Koshland-Nemethy-Filmer [67]. (c) Frieden’s model that adapts the Monod-Wyman-Changeux model to include dissociation [68]. (d) Allostery without conformational change in the subunits [71, 72]. (e) A model proposed by Koshland that incorporates dissociation in an allosteric model [73].

Immediately after the concerted and sequential models were formulated others invoked subunit dissociation as part of allosteric control. In 1967 Frieden’s study of glutamate dehydrogenase led him to extend the concerted model to account for a dissociating/associating system (Figure 2c), i.e., the two conformations of the model have different quaternary structures and each conformation is limited to only one quaternary structure [68]. In the same year, Kurganov [69, 70] and Nichol, Jackson and Winzor [71] also proposed mathematical models for the allosteric control of a dissociating/associating oligomer whose different quaternary forms have different functionality. One model proposed by Nichol, Jackson and Winzor [71] and later extended by Drozdov-Tikhomirov [72] accounted for allostery without invoking conformational change in a subunit (Figure 2d). Notably, in 1970 Koshland described dissociation in an allosteric system as means to attenuate the allosteric response [73]. One of the theoretical models proposed therein is shown in Figure 2e. This model represents the phenomenon that has come to be known as auto-inhibition, as in the action of the epidermal growth factor receptor [74], and is prescient of the minimal description of a morpheein, described below.

The Morpheein Model of Allostery

The original concerted and sequential models of allostery, promoting the view of stable oligomers, remain the most often considered. Since 1970, the relationship between dissociation/association and allostery has been rarely invoked; there have been only five reviews [75–78], the most recent of which was more than fifteen years ago, and two books [79, 80], which consider this relationship. However, throughout the past decade we have characterized a protein for which allostery involves oligomer dissociation, conformational change in the dissociated state, and reassembly to a structurally and functionally distinct oligomer [7, 8, 34, 81–89]. Our initial unwillingness to embrace the possibility for this particular type of quaternary structure dynamic was seated in our general appreciation for the one sequence → one structure paradigm, which we, like most, considered to be applicable on the level of quaternary structure. This enlightening system, which is described in detail in an accompanying article [33], is introduced below along with consideration of whether other proteins may behave in a similar fashion. The homooligomeric protein is porphobilinogen synthase (PBGS), which catalyzes the first common step in the synthesis of the tetrapyrrole pigments (heme, chlorophyll, vitamin B12). PBGS can exist as a high activity octamer that can dissociate to dimers; the dimers can populate alternate conformations; and one alternate dimer conformation can assemble into a low activity hexamer (Figure 1c) [34, 81–85]. In some species there is an allosteric activator that stabilizes a subunit interface present in the octamer and absent in the hexamer [34]. These findings led to a new dissociating model for allosteric regulation termed the morpheein model [7, 8, 81]; this is described in more detail below.

Morpheein model of allosteric regulation

The morpheein model of allosteric regulation [7] marries conformational diversity with quaternary structure dynamics and establishes a physiological relevance to the pressure induced quaternary structure rearrangements described as conformational drift. In the context of the morpheein model, homo-oligomer assemblies readily associate and dissociate under physiologic conditions and there is sufficient conformational flexibility in the dissociated state to dictate formation of more than one kind of oligomeric assembly. A morpheein is defined to be a protein that exists as an equilibrium of quaternary structure assemblies such as is illustrated in Figure 1 by both a three-dimensional dice analogy (Figure 1a) and a two-dimensional geometric (Figure 1b) analogy. The assembled higher order oligomers are of finite multiplicity and different functionality. The individual states (morpheein forms) are linked by dynamic equilibria such that interchange between higher order oligomers must involve dissociation. The dissociated form has conformational flexibility and the specific conformation of this form determines which higher order oligomer is assembled. The change in conformation involves a small number of peptide backbone angles, such as hinge motion between domains; it does not involve protein unfolding/refolding. Assembly of oligomers is such that symmetrical contacts are maintained between the subunits in each oligomer (one dot to four dots for the dice; dashed line to thick line for the geometric shapes). The morpheein forms are all relatively close in energy, e.g. the low population states are present at some, albeit small, mole fraction. In this way the interconversion of morpheein forms can be accomplished under normal physiologic (native) conditions. The equilibrium can be drawn in one direction or the other through non-covalent ligand binding (Figure 1b); such allosteric ligands exert their effect on protein function by stabilizing one or another of the functionally distinct morpheein forms.

In the morpheein allosteric model, all forms are accessible in the presence and absence of allosteric effector molecules; the dynamic equilibria are merely shifted through binding of effectors. This is emphasized in Figure 1b by the position of the equilibria in the presence or absence of appropriately shaped allosteric effector molecules. While stable alternate conformations (or quaternary assemblies) are often associated with post-translational modifications, interchange between morpheein forms occurs without such modification. Without chemical modification, the ready interchange of morpheein forms demands that they be of similar energy, as has been demonstrated for the morpheein forms of PBGS [34, 81–85]. There may however be a substantial kinetic barrier to the interconversion process.

What rules might dictate how identical subunits can rearrange?

In general, protein subunits assemble with themselves (homomeric assembly) such that they retain an element of symmetry wherein equivalent surfaces of equivalent monomers are in equivalent environments (see Figure 1). If one monomer has, for instance, residue X in a hydrogen bond with residue Y of another subunit, then it is preferred that all residues X of each subunit are in a hydrogen bond with all residues Y of a neighboring subunit. Complete dissociation of an oligomer (Figure 1) releases all these interactions simultaneously, retaining the equivalence of the protein surfaces, one subunit to the next. But removal of one subunit from the trimer or tetramer would result in a loss of this equivalence and establish an asymmetric structure. In a given environment (pH, temperature, ionic strength), the physical chemical forces governing association of the subunits are equivalent for all subunits and the system will strive to retain symmetry. Thus, there are many oligomeric assemblies larger than a dimer where partial dissociation creates asymmetry. For the PBGS octameric assembly, illustrated in Figure 3, loss of one subunit or one dimer would result in such asymmetry; splitting the octamer in half by removing two pro-octamer dimers also results in asymmetry. However, separating the octamer into two halves in a process that cleaves each pro-octamer dimer (along the barrel-to-barrel interface) would retain symmetry. The resulting tetramers would each contain four dangling N-terminal arms. Although there are valid arguments against this latter example, such as the significance of the pulled apart arms to the structural integrity barrel-barrel contacts, symmetry is retained. However, one way that PBGS could dissociate and still retain both symmetry and two out of the three surface-to-surface contacts would be to simultaneously dissociate to four dimmers (Figure 1c). As described above, it is the need to maintain symmetry and the orientation of the Nterminal arm that drives formation of the hexamer and/or octamer of PBGS. For an in depth discussion of oligomeric assembly, the reader is referred to a review article by Goodsell and Olson [90].

Figure 3. Generation of protein asymmetry during multimer disassembly.

Using octameric PBGS as an example. A top and side view of the protein where the αβ-barrel domains are dark blue and the N-terminal arm is red. Similar views of the asymmetry generated upon removal of b) one subunit, c) one pro-octamer dimer, and d) two adjacent pro-octamer dimers, e) a symmetric disassembly results from removal of all four subunits on one hemisphere of the octamer.

Morpheeins expand our understanding of disease and drug action

Inborn errors of metabolism often result from mutations that alter the function of essential proteins. If the natural function of a particular protein relies on its ability to equilibrate between morpheein forms, then single amino acid variations that alter the equilibrium of such forms can result in a disregulation of said protein function and cause or contribute to a disease state. This is indeed the case for human PBGS in relation to the disease of ALAD porphyria; all of the naturally occurring mutations of human PBGS that are associated with the disease ALAD porphyria have been shown to shift the quaternary structural equlibria toward the low activity hexameric assembly [83]. Such diseases can be considered among the conformational diseases. Hence, identification of proteins that function as morpheeins can improve our understanding of the structural basis of human diseases associated with the function of these protein and/or variations in disease susceptibility. Several of the putative morpheeins in Table 2 are associated with inborn errors of metabolism. These are 1) alpha-galactosidaseA, which is associated with Fabry disease, 2) the ATPase of the ABCA1 transporter, which is mutated in Tangier’s disease and familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency, 3) cystathionine-β-synthase, for which some mutations cause a form of homocystinuria, 4) dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase, associated with E3-deficient maple syrup urine disease and lipoamide dehydrogenase deficiency, 5) NAD(+)-dependent mitochondrial malic enzyme, where mutations are related to certain hereditary forms of epilepsy, 6) phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency, which causes phenylketonuria, and 7) pyruvate kinase, whose deficiency is the most common cause of hemolytic anemia. For each of these proteins, there are one or more publications that justify a model of functional control via equilibrium of alternate protein assemblies (see Table 2).

Just as understanding disease mechanism may be improved by considering that certain proteins function as morpheeins, so too can our understanding of the mechanism of action of effective therapeutics whose mechanism is not otherwise explained. In proof of this concept small molecule allosteric inhibitors of PBGS, which function by stabilizing the inactive hexameric assembly, have been identified [84, 88, 89]. Following the identification of the morpheein character of medically relevant proteins, comes the possibility of designing or discovering allosteric inhibitors or activators of these proteins. The literature suggests that small molecule allosteric stabilization of alternative quaternary structures may be the an effective approach to finding inhibitors directed against prominent drug targets such as tumor necrosis factor α [91] or HIV integrase [92]. To this end the characteristics of a morpheein as these may aid in the identification of such proteins are discussed.

Characteristics that suggest a protein functions as a morpheein

There are myriad characteristics that suggest, but do not prove, that a particular protein may function as a morpheein. Table 2 provides a list of proteins that exhibit one or more of these characteristics and are thus suspect of being able to exist as an equilibrium of functionally distinct, non-additive quaternary structure assemblies or morpheein forms. Each entry in Table 2 includes at least one reference which the reader can use to begin exploring the putative morpheein nature of this protein. Some suggestive characteristics are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Some characteristics of a morpheein ensemble.

a. Due to the law of mass action the specific activity of a morpheein protein may vary with concentration of the protein. The example shows a lower activity smaller multimer in equilibrium with a higher activity larger multimer (e.g. [244]). The protein concentration axis covers three orders of magnitude. b. Hysteresis in the accumulation of product as a function of time. The example shown is of a situation where a more active morpheein form accumulates upon transfer of protein to assay conditions with the consequence that the rate of product production increases with time (e.g. [81]). In a contrasting situation where a less active morpheein form accumulates upon transfer of protein assay conditions a slowing in the rate of product production would be observed. c. A non-Michaelis Menten relationship of activity versus substrate concentration can result if more than one morpheein form is present [83]. Shown is an example in which two morpheein forms with vastly different affinities for the substrate co-exist. To see this, substrate concentration must be varied 3–5 log units. d. The order of addition of reaction components. GDP-mannose dehydrogenase (GMD) provides a striking example of order of addition effects where GDP-mannose and NAD+ are substrates while phosphate and GMP are allosteric regulators [95]. In Tris, initiated by GMD (○); in Tris, initiated by NAD+ (●); in Tris, initiated by GDP-mannose (■); in Tris + 100 mM GMP, initiated by GMD (□); in potassium phosphate, initiated by GMD (♦).

Protein concentration dependent specific activity (Figure 4a)

Specific activity (units of enzyme activity per protein mass) is a value often used during protein purification to assess protein purity. In the case of monomeric enzymes, or stable enzyme oligomers, specific activity is expected to be independent of the concentration of the enzyme used in the assay. However, for an equilibrium of morpheeins forms, if rapid interchange of oligomeric assemblies is occurring during the assay, the observed specific activity may be dependent upon the concentration of the enzyme in the assay mixture. This relationship derives from the law of mass action, which favors the largest oligomer as the protein concentration is increased in the range of its inherent dissociation constant. The illustration in Figure 4a refers to a situation where the largest oligomer is the most active. In the case where a smaller oligomer is most active, there will be an inverse relationship between protein concentration and specific activity, as has been reported for purine nucleoside phosphorylase [93]. However, it is important to note that one may only recognize such a protein concentration dependent specific activity if one is varying the protein concentration within the range (+/− one order of magnitude) of the apparent K0.5. Outside that range the effect will be too small to discriminate from experimental error.

Kinetic hysteresis

One is classically taught that initial rates of enzyme catalyzed reactions should display a linear increase in the concentration of product. However, in the case of an enzyme that functions as a morpheein, this may not be so. Upon dilution into assay buffer, a lag (shown in Figure 4b) or a burst in activity may be apparent as the equilibrium of morpheein forms adjusts to assay conditions. In the example in Figure 4b the assay conditions promote a shift to a more active morpheein form and the rate of product production increases with time. A shift to a less active form would have the opposite with a decrease in the rate of product production occurring with time. The term hysteresis was coined by Frieden in 1970 to describe non-linear kinetics [94]. Subsequently Kurganov presented mathematical models to explain various hysteretic behavior [79]. While the early work on kinetic hysteresis did not have the luxury of the structural insight gained from a decade of work on the PBGS quaternary structure equilibrium, one explanation for hysteretic behavior is a switch in the distribution of morpheein forms. The work of Frieden and Kurganov also points to the fact that kinetic hysteresis is a possible characteristic of an enzyme that functions as a morpheein, but it is not a diagnostic tool by itself.

Non-traditional Michaelis Menten kinetics

The existence of multiple forms of an enzyme may be reflected by non-traditional Michaelis-Menten plots. Generally it is expected that a Michaelis-Menten plot will be hyperbolic unless there is some phenomenon such as product inhibition to perturb this trend. In the case of a morpheein it is possible that two or more catalytically active forms may be present. Provided that the affinities of the various forms for the substrate are sufficiently different, a nontraditional Michaelis-Menten plot will be produced that consists of more than one hyperbola, the number of which corresponds to the number of active forms present in the assay. For example, the predominant forms of human PBGS are the octamer and the hexamer. These two forms have vastly different Km values and the result is a double hyperbolic relationship between substrate concentration and activity. However, to see this relationship, it is necessary that experimental substrate concentrations cover the range of the two Km values [85].

Multiple quaternary structures

Often multiple quaternary structural forms that are visualized by gel filtration chromatography or native-PAGE are viewed as representing an impure sample. This is especially true if one or more of the separated forms are found to be inactive. However, if a protein functions as a morpheein, the multiple quaternary structures may be functionally distinct forms of the same protein. Rechromatography under different conditions may produce a different distribution of quaternary structural forms and even more confounding is the fact that these forms may have vastly different functions (see moonlighting proteins below). In addition to separation by traditional sizing methods the surface charge differences between the different quaternary structural forms may allow separation by ion-exchange chromatography. For example, the octameric, hexameric, and dimeric forms of PBGS can be separated by anion exchange chromatography [34, 81, 85].

pH profile effects

pH profiles also may depend on the conditions under which they are obtained. For example, the alkaline limb of the human PBGS pH-activity profile is due at least in part to the pH dependence of the quaternary structure equilibrium. High pH favors the less active hexamer compared to the more active octamer [85].

Order of addition effects

Incubation conditions prior to addition of the reaction initiating compound can influence the distribution of morpheein forms of a protein. GDP-mannose dehydrogenase (GMD) provides a striking example of order of addition effects [95]. The substrates for GMD are GDP-mannose and NAD+, and both phosphate and GMP act as allosteric effectors [95]. As shown in Figure 4d the four very different reaction rate curves are produced when the assays were carried out using four different orders of addition of reactants and/or allosteric effectors. Similar phenomena have also been referred to as enzyme memory [96].

Moonlighting proteins

It has become common to find that one protein has multiple unrelated functions; these proteins are said to moonlight [97]. One notable example is the glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase which has been reported to have many activities unrelated to glycolysis [98–104]. It is possible that proteins that moonlight may not always do so as the same quaternary structure assembly. It is not clear if glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) performs all of its activities as the tetramer believed to be functional in glycolysis. It may be possible to modulate a preferred function of multimeric moonlighting proteins with small molecules that modulate an equilibrium of morpheein forms.

Morpheeins in relation to other oligomerizing proteins

Morpheeins represent a subset of oligomerizing proteins. The features that distinguish morpheeins from other oligomerizing proteins are that they are homo-oligomeric, of finite stoichiometry, must dissociate/associate to interchange between functionally distinct multimers, and assembly of oligomers is autonomous, i.e., that is oligomer assembly occurs without the need for covalent modification or the presence of a template/scaffold. We have chosen to limit the definition of morpheeins to homo-oligomeric proteins because the archetypical morpheein PBGS is such a protein. There is no direct evidence for or against hetero-oligomers existing in dynamic equilibria such that they dissociate, change shape and come back together differently to regulate function. However, on the simplest level hetero-oligomers can be viewed as one protein being regulated by interaction with another; a scenario that does not require morpheein-like behavior.

Among homo-oligomeric proteins, morpheeins represent a distinct category. Conformational flexibility is evident in many homo-oligomers that do not follow the morpheein model. For example, prions adopt at least two conformations; one that does not oligomerize and one that does [105]. In terms of the morpheein model these could be viewed as conformations of a fundamental unit. However, oligomerization of prions differs markedly from that of morpheeins. The symmetry of oligomerization does not dictate a size limit for the oligomer such that large fibrils may be formed. Furthermore the thermodynamics of fibril formation is generally not amenable to a physiologically relevant and readily reversible mechanism for allostery.

Virus coat proteins also bear similarities to, but are not, morpheeins. These proteins must assemble to form a capsid around the virus genome to protect it from damage but upon invading a cell the coat must disassemble to allow infection by release of the genome. These properties imply that there are two conformations of the protein only one of which is capable of oligomerization. To form the capsid the proteins assemble with either a helical or an icosahedral symmetry in which the subunits may lie in quasi-equivalent environments [106, 107]. However, the requirement to form a stable barrier necessitates that the oligomer is not in dynamic equilibrium, but that the oligomer forming conformation is a metastable state that remains until some trigger removes a barrier to a conformational change that favors dissociation. Further distinctions are that, this conformational change must occur in the oligomer, not all capsids are homo-oligomeric, and the genome or some scaffold protein generally forms a template for the capsid.

Summary

Herein the morpheein model of allosteric regulation (Figure 1) and the history of thought on protein quaternary structure, dynamics and allostery that preceded it are detailed. In this model, subunits of an oligomer must dissociate to allow conformational change. The conformation of the dissociated protein dictates the symmetry of assembly of higher order oligomers. Consideration that a homo-oligomeric protein may be a morpheein opens up many new avenues for the understanding of protein function and the basis for and the treatment of disease. The insight gained into these facets of PBGS that are detailed in an accompanying review testify to this.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sarah Lawrence for useful discussion.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01E5003654 (EKJ) and CA06927 and an Appropriation from the Commonwealth of PA

Abbreviations used

- PBGS

Porphobilinogen synthase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Murzin AG. Science. 2008;320:1725–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.1158868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fink AL. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005;15:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James LC, Tawfik DS. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:361–368. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00135-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tompa P. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27:527–533. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux JP. J. Mol. Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monod J, Changeux JP, Jacob F. J. Mol. Biol. 1963;6:306–329. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(63)80091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaffe EK. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence SH, Jaffe EK. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2008;36:274–283. doi: 10.1002/bmb.20211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohr C, Hasselbach KA, Krogh A. Skand. Arch. Physiol. 1904;16:402–412. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill AV. J. Physiol. Proc. 1910;40:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barcroft J, Hill AV. J. Physiol. 1910;39:411–428. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1910.sp001350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill AV. J. Biol. Chem. 1922;51:359–365. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douglas CG, Haldane JS, Haldane JB. J. Physiol. 1912;44:275–304. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1912.sp001517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill AV. Biochem. J. 1913;7:471–480. doi: 10.1042/bj0070471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill AV. Biochem. J. 1921;15:577–586. doi: 10.1042/bj0150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barcroft J, Bock AV, Hill AV, Parsons TR, Parsons W, Shoji R. J. Physiol. 1922;56:157–178. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1922.sp001999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown WEL, Hill AV. Proc. R. Soc. London Series B. 1923;94:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adair GS. Proc. Roy. Soc A. 1925;109:292–300. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pauling L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1935;21:186–191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.21.4.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackers GK, Holt JM. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:11441–11443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiu Y, Maillett DH, Knapp J, Olson JS, Riggs AF. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:13517–13528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singer SJ, Itano HA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1959;45:174–184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.45.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Svedberg T. Proc. R. Soc. London. 1939;127:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Svedberg T. Nature (London, U. K.) 1931;128:999–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sjogren B, Svedberg T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1930;52:3650–3654. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svedberg T. Nature (London, U. K.) 1929;123:871. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svedburg T, Estrup K, Chem Z. Ind. Kolloide. 1912;9:259–261. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linderstrom-Lang K, Schellman JA. Protein structure and enzyme activity. In: Boyer PD, Lardy H, Myrback K, editors. The Enzymes. Vol. 1. 1959. pp. 443–510. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klotz IM, Langerman NR, Darnall DW. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1970;39:25–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.39.070170.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levy ED, Boeri Erba E, Robinson CV, Teichmann SA. Nature. 2008;453:1262–1265. doi: 10.1038/nature06942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grueninger D, Treiber N, Ziegler MO, Koetter JW, Schulze MS, Schulz GE. Science. 2008;319:206–209. doi: 10.1126/science.1150421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janin J. Science. 2008;319:165–166. doi: 10.1126/science.1152930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaffe EK, Lawrence SH. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011 Oct 19; In press, Available online. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breinig S, Kervinen J, Stith L, Wasson AS, Fairman R, Wlodawer A, Zdanov A, Jaffe EK. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:757–763. doi: 10.1038/nsb963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauling L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940;62:2643–2657. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landsteiner K. The specificity of serological reactions. Dover Publications; 1936. reprinted 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanger F. Adv. Protein Chem. 1952;7:1–67. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodgkin DC. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1979;325:120–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1979.tb14132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perutz MF. Brookhaven Symp. Biol. 1960;13:165–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischer E. Ber. Dt. Chem. Ges. 1894;27:2985–2993. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koshland DE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1958;44:98–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krissinel E, Henrick K. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dutta S, Burkhardt K, Young J, Swaminathan GJ, Matsuura T, Henrick K, Nakamura H, Berman HM. Mol. Biotechnol. 2009;42:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12033-008-9127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu Q, Canutescu AA, Wang G, Shapovalov M, Obradovic Z, Dunbrack RL., Jr J. Mol. Biol. 2008;381:487–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byeon IJ, Louis JM, Gronenborn AM. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;333:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00928-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirsten Frank M, Dyda F, Dobrodumov A, Gronenborn AM. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:877–885. doi: 10.1038/nsb854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gronenborn AM. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sela M, White FH, Jr, Anfinsen CB. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1959;31:417–426. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(59)90016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anfinsen CB. Science. 1973;181:223–230. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldberger RF, Epstein CJ, Anfinsen CB. J. Biol. Chem. 1963;238:628–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nickerson KW, Day RA. Curr. Mod. Biol. 1969;2:303–306. doi: 10.1016/0303-2647(69)90016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Epstein C, Schechter AN. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1968;151:85–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb11880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borgia MB, Borgia A, Best RB, Steward A, Nettels D, Wunderlich B, Schuler B, Clarke J. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levinthal C. Sci. Am. 1966;214(6):42–52. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0666-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nickerson KW. J. Theor. Biol. 1973;40:507–515. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(73)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kitto GB, Wassarman PM, Kaplan NO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1966;56:578–585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.2.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hotchkiss RD. Brookhaven Symp. Biol. 1964;17:174–183. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weber G. Biochemistry. 1986;25:3626–3631. doi: 10.1021/bi00360a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dill KA, Chan HS. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 1997;4:10–19. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frieden C. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2334–2344. doi: 10.1110/ps.073164107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adelberg EA, Umbarger HE. J. Biol. Chem. 1953;205:475–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Umbarger HE. Science. 1956;123:848. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3202.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yates RA, Pardee AB. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;227:677–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gerhart JC, Pardee AB. J. Biol. Chem. 1962;237:891–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Changeux JP. J. Mol. Biol. 1962;4:220–225. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(62)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koshland DE, Jr, Nemethy G, Filmer D. Biochemistry. 1966;5:365–385. doi: 10.1021/bi00865a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frieden C. J. Biol. Chem. 1967;242:4045–4052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kurganov BI. Molekulyarnaya Biologiya (Moscow) 1968;2:430–447. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kurganov BI. Molekulyarnaya Biologiya (Moscow) 1967;1:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nichol LW, Jackson WJH, Winzor DJ. Biochemistry. 1967;6:2449–2456. doi: 10.1021/bi00860a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]