Abstract

Background

Though patients who receive surgery from high-volume surgeons tend to have better outcomes, black patients are less likely to receive surgery from high-volume surgeons.

Objective

Among men with localized prostate cancer, we examined whether disparities in use of high-volume urologists resulted from racial differences in patients being diagnosed by high-volume urologists and/or changing to high-volume urologists for surgery.

Research Design

Retrospective cohort study from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare data

Subjects

26,058 black and white men in SEER-Medicare diagnosed with localized prostate cancer from 1995 to 2005 that underwent prostatectomy. Patients were linked to their diagnosing urologist and a treating urologist (who performed the surgery).

Measures

Diagnosis and receipt of prostatectomy by a high-volume urologist, and changing between diagnosing and treating urologist

Results

After adjustment for confounders, black men were as likely as white men to be diagnosed by a high-volume urologist; however, they were significantly less likely than white men to be treated by a high-volume urologist (Odds ratio 0.76, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.67, 0.87). For men diagnosed by a low-volume urologist, 46.0% changed urologists for their surgery. Black men were significantly less likely to change to a high-volume urologist (Relative Risk Ratio 0.61, 95%CI 0.47, 0.79). Racial differences appeared to reflect black and white patients being diagnosed by different urologists and having different rates of changing after being diagnosed by the same urologists.

Conclusions

Lower rates of changing to high-volume urologists for surgery among black men contribute to racial disparities in treatment by high-volume surgeons.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, Healthcare Disparities, High-volume, Provider Changing

Introduction

Receiving surgery from a high-volume surgeon has been associated with improved outcomes for a wide variety of procedures including lower rates of 30-day surgical complications, lower rates of mortality, and, for cancer surgery, lower rates of recurrence.1,2 However, access to high-volume surgeons remains unequal. Racial disparities in treatment by high-volume surgeons have been demonstrated for multiple cancer3-8 and non-cancer surgeries,5,6,9 and have persisted over time.8

Though racial disparities in treatment by high-volume surgeons have been widely documented, reasons underlying these disparities remain poorly understood. In general, there are two pathways through which a patient may be treated by a high-volume surgeon: (1) the patient may be diagnosed by a high-volume surgeon and remain with that surgeon or change to another high-volume surgeon for treatment; or (2) the patient may be diagnosed by a low-volume surgeon and then change to a high-volume surgeon for treatment. Understanding the relative contribution of each pathway to racial disparities in use of high-volume surgeons is an important step towards addressing these disparities.

We focus on access to racial disparities in use of high-volume urologists for men with prostate cancer. In 2010, an estimated 217,730 men were diagnosed with prostate cancer in the US, and radical prostatectomy is one of the primary treatment options.10 High-volume urologists tend to have lower rates of postoperative and urinary complications,11 shorter hospital lengths of stay,12 decreased likelihood of positive surgical margins,12 and improved recurrence-free survival.3 However, previous literature suggests that black men with localized prostate cancer are less likely to be operated on by high-volume urologists and at high-volume hospitals than white men.12

We examined the degree to which differences in treatment by a high-volume urologist between black and white men with localized prostate cancer is attributable to differences in rates of diagnosis by a high-volume urologist versus differences in rates of changing from a low-volume urologist at diagnosis to a high-volume urologist for treatment. We further examine to what extent racial differences in rates of changing from a low-volume to a high-volume urologist are attributable to black and white men being diagnosed by different low-volume urologists or having different rates of changing to high-volume urologists after being diagnosed by the same low-volume urologists.

Methods

Data Sources

The study was a retrospective, observational cohort study using registry and administrative claims data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database. The SEER-Medicare database links patient demographic and tumor-specific data collected by SEER cancer registries to longitudinal health care claims for Medicare enrollees.13 This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Boards.

Study Population

We identified men age 65 years or older who were diagnosed with prostate cancer from 1995 to 2005 in one of the SEER sites. Data on patients with incomplete Medicare records (i.e. those enrolled in health maintenance organizations or not enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare program) were excluded. The sample was limited to 29,751 men with localized or regional disease defined as American Joint Committee on Cancer Stage 1, 2 or 3 without nodal invasion or metastases who underwent prostatectomy. Prostatectomy was identified from Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and physician/supplier component files as described previously.14,15 These men were matched to a diagnosing (29,398; 98.8%) and treating urologist (27,274; 91.7%), see below. Patients of all race/ethnicity were included when classifying urologists’ prostatectomy volume. However, the sample was limited to white and black men for analyses to examine black/white disparities (N=26,058).

Assignment of patients to urologists

Diagnosing urologist

The urologist most likely to have diagnosed the patient's prostate cancer was defined as the urologist who billed for a prostate biopsy in the three months prior to the date of diagnosis. If no claim was identified, then the urologist was chosen based on the following order: (a) the urologist who billed for a claim on the date of diagnosis, (b) the urologist who billed for the greatest number of visits in the three month window prior to diagnosis, and (c) the urologist who billed for the greatest number of claims in the three months following diagnosis. Provider specialty was determined using codes from the Medicare Physician Identification and Eligibility Registry data. We focused on diagnosing urologist because of their potential role in treatment selection. Patients were matched to 2,538 unique diagnosing urologists.

Treating urologist

The urologist who billed for the patient's prostatectomy was defined as the treating urologist. Patients were matched to 2,000 treating urologists.

Urologist prostatectomy volume

Yearly volume was identified by summing the number of prostatectomies for which a urologist billed divided by the total number of years in which the urologist performed at least one prostatectomy. Urologists were classified into four volume categories based on quartiles of the patient cohort. The median patient volume for treating urologists in the lowest volume quartile was 1.8 patients (range 1.0 to 2.5) to 9.8 patients in the highest quartile (range 6.8 to 23.5). The same cut-points for patient volume were applied to the diagnosing urologist's surgical volume. Diagnosing urologists who did not bill for any prostatectomies during the study period (N=695) were given a volume of zero and placed in the lowest volume quartile. High-volume for diagnosing and treating urologists is defined as being in the top quartile of the sample distribution, and low-volume is defined as the bottom three quartiles.

Patient and tumor characteristics

Age was classified as 65 to 74 and 75 and over. Individuals were considered black if they were classified as black in either data source without a co-designation of Hispanic or Asian and white if they were classified as white in either data file without a classification of black. Patient comorbidities were identified by classifying all available inpatient and outpatient Medicare claims for the 90 day interval preceding prostate cancer diagnosis into 46 categories.16-19 For clarity, comorbidity is reported as the number (0, 1, ≥2) of the possible 46 comorbidity groups identified for each patient. Marital status was classified as married, single, or unknown. U.S. Census information was used as a proxy for individual measures of socioeconomic status. Men were linked to their census tract and, when not available, zip code to determine median income which was classified into four quartiles. Tumor grade corresponds to Gleason status and was categorized as well differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated and undifferentiated, and unknown.

Statistical Analyses

After presenting descriptive statistics by patient race, we estimate a multivariable logistic regression model where the dependent variable is the volume status (high/low) of the treating urologist. The model adjusts for sociodemographic factors, comorbidities, tumor grade and stage, SEER site, and year of diagnosis. We present a similar multivariable logistic regression model with the volume status of the diagnosing urologist as the dependent variable.

In the next series of models, we estimate multinomial logistic regression models for patients diagnosed by low and, separately, high-volume urologists. The dependent variable categorizes patients according to whether they: (a) did not change physicians (baseline category), (b) changed to a low-volume treating urologist, and (c) changed to a high-volume treating urologist. We clustered standard errors by patients’ diagnosing urologists.

For patients diagnosed by low-volume urologists, we then explore the extent to which overall racial differences in rates of changing may be attributable to systematic differences between urologists who care for patients of different races (between-doctor differences) versus variation in how urologists care for patients of different races (within-doctor differences). That is, black patients diagnosed by low-volume urologists might be more or less likely to change physicians than white patients also diagnosed by low-volume urologists because physicians who diagnose predominantly black patients may care for patients differently compared with those who diagnose predominantly white patients, or because physicians care for their black patients differently than their white patients. The explanations are not mutually exclusive. To accomplish this empirically, we specified a hybrid fixed effects model20,21 by adding to the above multinomial regression model covariates that specify, for each diagnosing urologist, the proportion of his/her patients belonging to each racial group. The coefficients on these variables capture between-doctor differences whereas the coefficients on the patient-level race/ethnicity variables identify the within-doctor differences.22 As a robustness check of the within-doctor differences, we estimate a conditional fixed effects logistic regression of the dichotomous outcome of change to a high-volume treating urologist. Analyses were conducted using Stata 11.1. Hypothesis tests were two-sided and used a Type I error rate of 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the patient population, stratified by patient race. With the exception of year and tumor grade, significant racial differences were noted with each sociodemographic and clinical characteristic. Similar to prior studies, black men were less likely to have had their surgery from a high-volume urologist and this difference persisted after adjustment for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (Odds Ratio [OR] 0.76, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.67, 0.87) (Table 2). In addition, men living in the highest income neighborhoods, patients with lower levels of comorbidity, and those with higher Gleason scores were significantly more likely to be treated by high-volume urologists.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients, by patient race

| White | Black | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 24,097 (100%) | 1,961 (100%) | |

| Age | |||

| <75 | 21,329 (88.5) | 1,794 (91.5) | |

| 75+ | 2,768 (11.5) | 167 (8.5) | <0.001 |

| comorbidity | |||

| 0 | 9,039 (37.5) | 461 (23.5) | |

| 1 | 8,048 (33.4) | 645 (32.9) | |

| 2+ | 7,010 (29.1) | 855 (43.6) | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 19,729 (81.9) | 1,284 (65.5) | |

| Unmarried | 3,395 (14.1) | 605 (30.9) | |

| Unknown | 973 (4.0) | 72 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Income | |||

| Lowest | 5,305 (22.0) | 1,154 (58.9) | |

| Mid-low | 6,165 (25.6) | 402 (20.5) | |

| Mid-high | 6,303 (26.2) | 246 (12.5) | |

| Highest | 6,324 (26.2) | 159 (8.1) | <0.001 |

| Grade | |||

| well-differentiated | 699 (2.9) | 44 (2.2) | |

| moderately differentiated | 15,827 (65.7) | 1,220 (62.2) | |

| poorly differentatied | 7,373 (30.6) | 666 (34.0) | |

| unknown | 198 (0.8) | 31 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Tumor stage | |||

| 1 | 7,442 (30.9) | 627 (32.0) | |

| 2 | 15,434 (64.1) | 1,235 (63.0) | |

| 3 | 1,221 (5.1) | 99 (5.1) | 0.6 |

| Volume status of diagnosing urologist | |||

| Low | 20,640 (85.6) | 1,780 (90.8) | |

| High | 3,457 (14.4) | 181 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Volume status of treating urologist | |||

| Low | 17828 (74.0) | 1620 (82.6) | |

| High | 6269 (26.0) | 341 (17.4) | <0.001 |

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression model for odds of diagnosis and treatment by a high volume urologist, respectively

| OR of Diagnosed by a High Volume Urologist * | OR of Treatment by a High Volume Urologist ^ | |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 0.86 (0.72-1.02) | 0.76 (0.67-0.87) |

| Age | ||

| <75 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 75+ | 1.46 (1.31-1.62) | 1.16 (1.06-1.27) |

| Comorbidity | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 1.01 (0.93-1.10) | 0.96 (0.89-1.03) |

| 2+ | 0.95 (0.86-1.04) | 0.83 (0.77-0.89) |

| Marital status | ||

| married | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| unmarried | 1.00 (0.90-1.12) | 0.90 (0.83-0.98) |

| unknown | 0.77 (0.63-0.95) | 0.72 (0.61-0.85) |

| Income | ||

| Lowest | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| mid-low | 1.50 (1.34-1.67) | 1.41 (1.29-1.54) |

| mid-high | 1.49 (1.33-1.67) | 1.54 (1.41-1.69) |

| highest | 1.67 (1.47-1.90) | 1.81 (1.64-2.00) |

| Tumor grade | ||

| well-differentiated | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| moderately differentiated | 1.00 (0.80-1.25) | 1.21 (1.00-1.47) |

| poorly differentiated | 0.93 (0.74-1.17) | 1.34 (1.10-1.63) |

| unknown | 0.98 (0.61-1.58) | 0.96 (0.64-1.43) |

| Tumor stage | ||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 0.89 (0.82-0.97) | 0.92 (0.86-0.99) |

| 3 | 0.78 (0.64-0.95) | 0.88 (0.76-1.02) |

Additionally adjusted for SEER site and year of diagnosis

>Hawaii, Atlanta, and rural Georgia dropped from analyses due to perfectly predicting the outcome

Rural Georgia dropped due to perfectly predicting the outcome

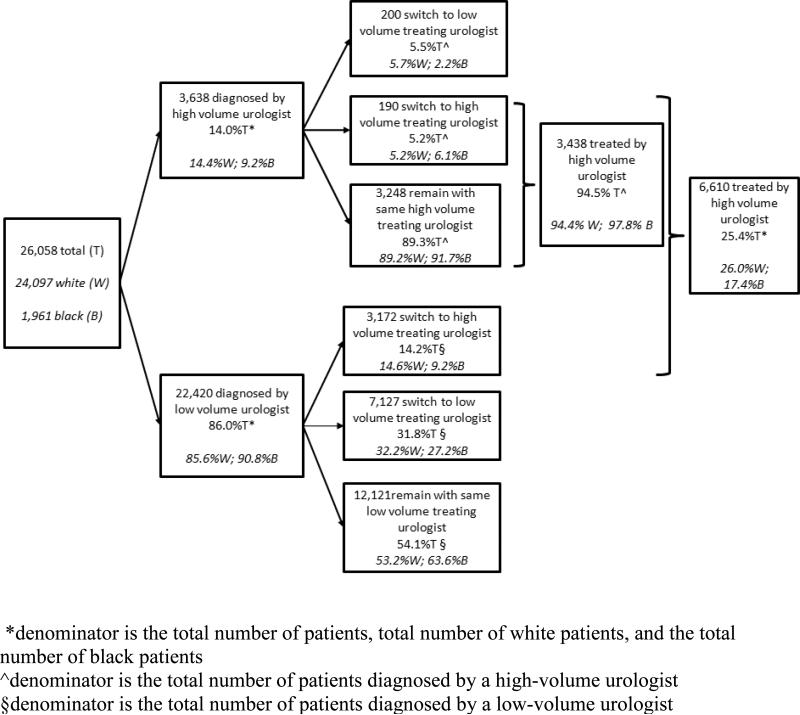

Figure 1 diagrams the flow of patients according to the volume of their diagnosing and treating urologist. In total, 14.0% of patients were diagnosed by a high-volume urologist and 86.0% were diagnosed by a low-volume urologist. A lower proportion of black patients were diagnosed by a high-volume urologist compared to white patients (9.2% versus 14.4%, p<0.001). However, this difference was no longer statistically significant after adjustment for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (Table 2). Being 75 years of age or older and residing in neighborhoods with higher incomes (compared to the lowest quartile) were significantly associated with higher likelihood of diagnosis by a high-volume urologist even after adjustment for other patient characteristics.

Figure 1.

Patient pathways according to volume of diagnosing and treating urologists, accounting for patient race and changing physicians

Among men diagnosed by a low-volume urologist, nearly half (46.0%) changed urologists for treatment: 14.2% to a high-volume urologist and 31.8% to a different low-volume urologist. Black men were less likely to change urologists (36.4% versus 46.8%) and less likely to change to a high-volume urologist than white men (9.2% versus 14.6%, p<0.001). In contrast, lower rates of changing urologists were observed among patients diagnosed by a high-volume urologist: only 10.7% changed urologists for treatment and approximately half of those patients (48.7%) changed to another high-volume urologist. There were no significant racial differences in changing urologists after being diagnosed by a high-volume urologist. Nearly all (94.5%) of patients diagnosed by a high-volume urologist received their prostatectomy from a high-volume urologist.

Separate multinomial logistic regression models were run among men diagnosed by low and high-volume urologists to examine the effect of multivariate adjustment on racial differences in changing urologists (Table 3). In both models, the outcome categories are not changing urologists (baseline), changing to a low-volume urologist, and changing to a high-volume urologist. Among men diagnosed by a low-volume urologist, black men remained significantly less likely to change to a high-volume urologist (RRR 0.61, 95%CI 0.47, 0.79) compared to white men. Black men were also significantly less likely to change to a different low-volume urologist (Relative Risk Ratio [RRR] 0.72, 95% CI 0.59, 0.87). Older age and higher number of comorbidities were associated with a lower likelihood of changing to either a high-volume or another low-volume urologist, whereas residing in higher income neighborhoods and a higher Gleason score were associated with an increased likelihood of changing to a high-volume urologist but not another low-volume urologist. Among men diagnosed by a high-volume urologist, racial differences in changing urologists were not statistically significant. However, men who resided in higher income neighborhoods were more likely to change to a different high-volume treating urologist (RRR 1.75, 95%CI 1.02, 2.98).

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression analyses among men diagnosed by low and high volume urologists, respectively showing patterns of remaining with same urologist and switching to low and volume treating urologists

| Low volume diagnosing urologist (N=22,420) | High-Volume Diagnosing Urologist (N-3638) ^ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change to low volume treating urologist* | Change to high volume treating urologist | Change to low volume treating urologist | Change to high volume treating urologist | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 0.72 (0.59-0.87) | 0.61 (0.47-0.79) | 0.35 (0.12-1.02) | 0.73 (0.30-1.76) |

| Age | ||||

| <75 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 75+ | 0.65 (0.58-0.74) | 0.76 (0.64-0.90) | 0.75 (0.48-1.18 ) | 0.91 (0.55-1.48) |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 0.94 (0.87-1.02) | 0.89 (0.81-0.97) | 0.79 (0.55-1.13) | 0.94 (0.69-1.28) |

| 2+ | 0.85 (0.78-0.92) | 0.70 (0.63-0.78) | 0.76 (0.52-1.09) | 0.83 (0.58-1.18) |

| Marital status | ||||

| married | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| unmarried | 1.06 (0.97-1.15) | 0.86 (0.75-0.97) | 1.18 (0.78-1.79) | 0.63 (0.33-1.21) |

| unknown | 1.57 (1.31-1.88) | 0.90 (0.68-1.18) | 2.13 (1.01-4.49) | 0.99 (0.38-2.61) |

| Income | ||||

| Lowest | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| mid-low | 1.06 (0.95-1.19) | 1.31 (1.10-1.55) | 1.08 (0.68-1.73) | 0.76 (0.48-1.20) |

| mid-high | 1.08 (0.95-1.23) | 1.58 (1.29-1.93) | 1.11 (0.70-1.76) | 1.16 (0.66-2.06) |

| highest | 1.25 (1.08-1.45) | 2.02 (1.64-2.47) | 1.45 (0.91-2.31) | 1.75 (1.02-2.98) |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| well-differentiated | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| moderately differentiated | 1.10 (0.89-1.34) | 1.57 (1.13-2.20) | 1.38 (0.44-4.32) | 1.77 (0.48-6.55) |

| poorly differentiated | 1.10 (0.89-1.35) | 1.95 (1.38-2.75) | 1.37 (0.42-4.42) | 2.33 (0.61-8.94) |

| unknown | 1.28 (0.88-1.87) | 1.10 (0.56-2.16) | 2.13 (0.36-12.74) | 1.57 (0.17-14.40) |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.00 (0.92-1.08) | 0.97 (0.86-1.10) | 1.01 (0.70-1.48) | 0.56 (0.36-0.88) |

| 3 | 1.12 (0.95-1.32) | 1.02 (0.82-1.28) | 0.75 (0.31-1.81) | 0.64 (0.27-1.50) |

Relative risk ratios, baseline category is men who did not Change

Additionally adjusted for SEER site and year of diagnosis

Hawaii, Atlanta, and rural Georgia dropped from high volume diagnosing urologist model due to no patients within categories

The last model examined whether rates of changing from a low-volume urologist could be attributed to black and white men being diagnosed by different low-volume urologists (between-doctor differences) versus black and white men having different rates of changing urologists after being diagnosed by the same low-volume urologists (within-doctor effects) (see Appendix Table 1). Among patients diagnosed by the same low-volume urologist, black patients were significantly less likely to change to a high-volume urologist compared to white patients (within-doctor effects, RRR 0.81, 95%CI 0.67, 0.97). Between-doctor effects were also significant with lower rate of changing to a high-volume urologist observed for all patients (regardless of race) who were diagnosed by urologists who had a greater proportion of black patients (RRR 0.36, 95%CI 0.17, 0.78). Using conditional logistic regression analyses led to qualitatively similar results for the within-doctor effects.

Discussion

In this analysis of prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer among elderly black and white men, we found that 40.1% of patients had a different diagnosing and treating urologist. Black men were less likely to undergo prostatectomy by a high-volume urologist than white men, and this disparity is largely attributable to lower rates of changing from a low-volume urologist at diagnosis to a high-volume urologist for treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that racial differences in treatment by a high-volume surgeon can be attributed to differences in the probability of changing surgeons. These results have important implications for efforts to address racial disparities in treatment by high-volume surgeons.

Currently very little is known about what drives the selection of a surgeon or movement from a low-volume to a high-volume surgeon for treatment. Prior research has tended to focus on why patients change their primary care providers.23-30 Trust and satisfaction have been shown to be important predictors of changing one's usual source of care,23-26,28-30 though these may have different meanings and be given different importance in the context of surgeon selection. Katz and colleagues found that women with breast cancer who chose their surgeon based on reputation were more likely to be treated by a high-volume surgeon compared to women who were referred or who chose based on proximity.31 Though surgeon volume may be correlated with reputation, it is uncertain whether patients and their referring doctors are directly aware of surgeon volume and how it factors into their decision-making relative to other attributes of the surgeon and his/her practice.32,33 Additionally, travel distance and the spatial distribution of high-volume urologists are likely important factors in surgeon selection.8,34,35 Evidence suggests that with the increasing centralization of prostate cancer surgery at high-volume hospitals, travel distances for patients have increased over time.35

While we did not directly assess the factors that determine racial differences in changing urologists, our results suggest that these differences arise both because of racial differences in which low-volume urologist black and white patients see at the time of diagnosis (between-doctor effects) and because of racial differences in changing from the same diagnosing urologist (within-doctor effects). The finding that black and white patients tended to be diagnosed by different low-volume urologists is not surprising given the considerable evidence supporting racial differences in providers in many other settings. High levels of segregation have been documented in the health care system, including primary and hospital care.36,37 Furthermore, providers who care for greater proportions of minority patients have been found to have different access to institutional resources and different quality and patient outcomes.38-40 Here, diagnosing urologists who treat a greater proportion of black patients are less likely to have their patients change to a high-volume urologist than diagnosing urologists who care for a smaller proportion of black patients. This difference occurs even though these urologists do not differ in surgical volume themselves and the patients all have the same insurance. While it is interesting to speculate that this pattern may be driven by factors such as practice structure (e.g. solo versus group), strength of hospital affiliation, or spatial distribution of providers with respect to where patients live, further research is needed to understand the factors underlying this variation.

Our results further suggest that black and white patients who are diagnosed by the same urologist have different rates of changing to high-volume surgeons. This pattern may relate to diagnosing urologists making different recommendations about referral for their black and white patients. Using clinical vignettes, Denberg and colleagues found that urologists gave different recommendations regarding prostate cancer treatment for patients of different races and social vulnerability.41 Differences in recommendations by patient race may stem from a variety of factors including physician-bias, heuristics or clinical uncertainty.42,43 Alternatively, patient decision-making and preferences may also drive the observed patterns of changing urologists.44 It is possible that differences in doctor-patient communication,45,46 trust,47,48 access to care,49 access to new technology (e.g. robotic prostatectomy),50 and ability to travel (e.g. financial, time, and psychological costs)34 may be important determinants of patient decisions to change urologists and may vary by race.

Black men were significantly less likely to be diagnosed by a high-volume urologist; however, this association was largely explained by other factors. In particular, diagnosis by a high-volume urologist was significantly associated with residing in a higher income areas. Higher area income was also strongly associated with changing from a low- to a high-volume urologist. Area-level income may correlate with the local availability of high-volume urologists and be a proxy for patient-level factors (e.g. economic resources, self-efficacy, and literacy) that may predispose individuals to receive their diagnosis and treatment from high-volume providers. It is possible that academic medical centers, which are frequently located in low-income, inner-city areas, may serve to mitigate these racial and socioeconomic disparities.51,52

The results of this study need to be considered in light of its limitations. First, prostatectomy volume is based on SEER-Medicare claims and has the potential for misclassification error. Medicare volume has been shown to accurately reflect total urologist prostatectomy volume, 2 but it is possible that patients traveling outside of a SEER site to receive treatment might lead to that treating urologist being inaccurately classified as low-volume as patients from outside of the SEER site are not captured. Second, our matching of patients to their diagnosing and treating physicians is incomplete. Third, the definition of the diagnosing urologist is based on claims data rather than patient-report and has the potential for misclassification error. Fourth, we are unable to account for practice structure that may affect both the rates of provider changing and decisions about which specific doctor to see. Fifth, though we use average patient volume over the years in practice in defining urologist volume, the number of cases a physician performs may vary year to year. Sensitivity analyses that defined high-volume providers as the top two quartiles of the sample distribution revealed qualitatively similar results (see Appendix Tables 2 and 3). Sixth, we exclude men who may have been referred to a high- or low-volume treating urologist but did not undergo surgery; this may lead to biased estimates of the association between race and changing urologists. Though we are unable to observe physician recommendations in claims data, we ran additional analyses examining rates of changing doctors among all men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer regardless of treatment (see Appendix 1 for a complete description). In adjusted analyses, black patients were significantly less likely to be diagnosed by a high-volume urologist (OR 0.85, 95%CI 0.78 – 0.93) and, among those diagnosed by a low-volume urologist, less likely to change to a high-volume urologist for their follow-up care. The results support our main findings. Finally, relying on urologist volume as the sole marker of quality has potential limitations, and disparities in recurrence-free survival and mortality persisted among black and white men who received their prostatectomy from medium and high-volume urologists and hospitals.3

The current study demonstrates high rates of changing urologists between diagnosis and surgical treatment. However, black men were significantly less likely to change overall and less likely to change to a high-volume urologist for their surgical treatment. The potential benefits of receiving care from high-volume urologists may be substantial—for example, compared to low-volume urologists, high-volume urologists tend to have fewer in-hospital (12% versus 22%)12 and late urinary complications (20 versus 28%),11 and longer time to recurrence (73 versus 60 months for the 25th percentile).3 However, in order to realize these benefits, interventions that attempt to reduce disparities in access to high-volume surgeons will require a deeper understanding of the specific pathways through which patients come to receive surgical care. Particular attention should be paid to disentangling the patient-, physician- and system-level factors that may impede black and low-income patients from changing urologists. To the extent that patient choice drives surgeon selection, then patients will need to be educated about the importance of asking about surgical volume. Awareness campaigns may also need to target referring physicians, and systemic-barriers (e.g. differential institutional resources, uneven spatial distribution of providers, barriers to patient-travel) may need to be addressed in order to mitigate these disparities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Pollack's salary was supported by the National Cancer Institute (5U54CA091409-10, Nelson (PI)) followed by a career development award from NCI and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (1K07CA151910-01A1). Dr. Ning's salary is supported by the P30 CA006927 Comprehensive Cancer Center Program at Fox Chase.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is Volume Related to Outcome in Health Care? A Systematic Review and Methodologic Critique of the Literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(6):511–520. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chowdhury MM, Dagash H, Pierro A. A systematic review of the impact of volume of surgery and specialization on patient outcome. Br J Surg. 2007;94(2):145–161. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gooden KM, Howard DL, Carpenter WR, et al. The Effect of Hospittal and Surgeon Colume on Racial Differences in Recurrence-Free Survival After Radical Prostatectomy. Med Care. 2008;46:1170–1176. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d696d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sosa JA, Mehta PJ, Wang TS, Yeo HL, Roman SA. Racial Disparities in Clinical and Economic Outcomes from Thyroidectomy. Ann Surg. 2007;246:1983–1991. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31812eecc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein AJ, Gray BH, Schlesinger M. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Use of High-Volume Hospitals and Surgeons. Arch Surg. 2010;145(2):179–186. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon Volume and Operative Mortality in the United States. New Engl J Med. 2003;349(22):2117–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neighbors CJ, Rogers ML, Shenassa ED, Sciamanna CN, Clark MA, Novak SP. Ethnic/Racial Dispariites in Hospital Procedure Volume for Lung Resection for Lung Cancer. Med Care. 2007;45:655–663. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180326110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stitzenberg KB, Meropol NJ. Trends in Centralization of Cancer Surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2824–2831. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothenberg BM, Pearson T, Zwanziger J, Mukamel D. Explaining disparities in access to high-quality cardiac surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(1):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer Statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010 doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Begg C, Riedel E, Bach P, et al. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy. New Engl J Med. 2002;347:693–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa011788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu JC, Gold KG, Pashos CL, Mehta SS, Litwin MS. Role of Surgeon Volume in Radical Prostatectomy Outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:401–405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potosky AL. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumre registry database. Med Care. 1993;31:732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang TL, Bekelman JE, Liu Y, et al. Physician Visits Prior to Treatment for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(5):440–450. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bekelman JE, Zelefsky MJ, Jang TL, Basch EM, Schrag D. Variation in Adherence to External Beam Radiotherapy Quality Measures Among Elderly Men with Localized Prostate Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1456–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris D, Coffey R. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silber J, Rosenbaum P, Trudeau M, et al. Multivariate matching and bias reduction in the surgical outcomes study. Med Care. 2001;39(10):1048–1064. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200110000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong YN, Mitra N, Hudes G, et al. Survival associated with treatment vs observation of localized prostate cancer in elderly men. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2683–2693. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris D, Coffey R. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allison PD. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Sage; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neuhaus JM, Kalbfleisch JD. Between- and within-cluster covariate effects int eh analysis of clustered data. Biometrics. 1998;54(2):638–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Begg MD, Parides MK. Separation of individual-level and cluster-level covariate effects in regression analysis of correlated data. Statist Med. 2003;22:2591–2602. doi: 10.1002/sim.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez HP, Wilson IP, Landon BE, Marsden PV, Cleary PD. Voluntary Physician Switching by Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Individuals. Med Care. 2007;45:189–198. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250252.14148.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marquis MS, Davies AR, Ware JE. Patient Satisfaction and Chnage in Medical Care Provider: A Longitudinal Survey. Med Care. 1983;21:821–829. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Federman AD, Cook EF, Phillips RS, et al. Intention to Discontinue Care Among Primary Care Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:668–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safran DG, J.E. M, Chang H, Murphy J, Rogers WH. Switching Doctors: Predictors of Voluntary Disenrollment from a Primary Physician's Practice. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorbero MES, Dick AW, Zwanziger J, Mukamel D, Weyl N. The Effect of Capitation on Switching Primary Care Physicians. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:191–209. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin HR, Gandek B, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, McHorney CA, Ware JE. Patients’ Ratings of Outpatient Visits in Different Practice Settings. JAMA. 1993;270(7):835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith MA, Bartell JM. Changes in Usual Sources of Care adn Perceptions of Health Care Access, Quality, and Use. Med Care. 2004;42:975–984. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keating NL, Green DC, Kao AC, Gazmararian JA, Wu VY, Cleary PD. How are patients’ specific ambulatory care experiences related to trust, satisfaction, and considering changing physicians? J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:29–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz SJ, Hofer TP, Hawley S, et al. Patterns and Correlates of Patient Referral to Surgeons for Treatment of Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:271–276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epstein AJ, Rosenquist JN. Tell Me Something New: Report cards and the referring physician. Am J Med. 2010;123:99–100. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinchen KS, Cooper LA, Levine D, Wang NY, Powe NR. Referral of Patients to Specialists: Factors Affecting Choice of Specialist by Primary Care Physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(3):245–252. doi: 10.1370/afm.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stitzenberg KB, Sigurdson ER, Egleston BL, Starkey RB, Meropol NJ. Centralization of Cancer Surgery: Implications for Patient Access to Optimal Care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4671–4678. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stitzenberg KB, Wong YN, Nielsen ME, Egleston BL, Uzzo RG. Trends in radical prostatectomy: centralization, robotics, and access to urologic cancer care. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith DB. The Racial Segregation of Hospital Care Revisted: Medicare discharge patterns and their implications. Am J Pub Health. 1998;88:461–463. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary Care Physicians Who Treat Blacks and Whites. New Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):575–584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. Concentration and Quality of Hospitals that Care for Elderly Black Patients. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1177–1182. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger D, Wennberg DE, Chandra A. Hospital-Level Racial Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Treatment and Outcomes. Med Care. 2005;43(4):308–319. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156848.62086.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trivedi AN, Sequist TD, Ayanian JZ. Impact of Hospital Volume on Racial Disparities in Cardiovascular Procedure Mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Denberg TD, Kim FJ, Flanigan RC, et al. The Influence of Patient Race and Social Vulnerability on Urologist Treatment Recommendations in Localized Prostate Carcinoma. Med Care. 2006;44:1137–1141. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000233684.27657.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The Effect of Race and Sex on Physicians’ Recommendations for Cardiac Catheterization. New Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):618–626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Health Services. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(2):146–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Armstrong K, Hughes-Halbert C, Asch DA. Patient Preferences Can Be Misleading as Explanations for Racial Disparities in Health Care. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):950–954. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-Centered Communication, Ratings of Care, and Concordance of Patient and Physician Race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–915. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, Gender, and Partnership in the Patient-Physician Relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Armstrong K, Ravenell KL, McMurphy S, Putt M. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Physician Distrust in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1283–1289. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Pub Health Report. 2003;118:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The Concept of Access: Definition and Relationship tp Consumer Satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127–140. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen PL, Gu X, Lipsitz SR, et al. Cost Implications of the Rapid Adoption of Newer Technologies for Treating Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1517–1524. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kahn K, Pearson M, Harrison M. Health Care for Black and Poor Hospitalized Medicare Patients. JAMA. 1994;271:1169–1174. al. e. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Armstrong K, Randall TC, Polsky D, Moye E, Silber JH. Racial Differences in Surgeons and Hospitals for Endometrial Cancer Treatment. Med Care. 2011;49:207–214. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182019123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.