Abstract

Depressed individuals are frequently excluded from weight loss trials because of fears that weight reduction may precipitate mood disorders, as well as concerns that depressed participants will not lose weight satisfactorily. The present study examined participants in the Look AHEAD study to determine whether moderate weight loss would be associated with incident symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation, and whether symptoms of depression at baseline would limit weight loss at 1 year. Overweight/obese adults with type 2 diabetes (n=5145) were randomly assigned to an Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) or a usual care group, Diabetes Support and Education (DSE). Of these, 5129 participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and had their weight measured at baseline and 1 year. Potentially significant symptoms of depression were defined by a BDI score ≥10. Participants in ILI lost 8.6±6.9% of initial weight at 1 year, compared to 0.7±4.8% for DSE (P<0.001, effectsize=−1.33), and had a reduction of 1.4±4.7 points on the BDI, compared to 0.4±4.5 for DSE (P<0.001, effectsize=0.23). At 1 year, the incidence of potentially significant symptoms of depression was significantly (RR=0.66, 95%CI=0.5,0.8; P<0.001) lower in the ILI than DSE group (6.3% vs. 9.6%). In the ILI group, participants with and without symptoms of depression lost 7.8±6.7% and 8.7±6.9%, respectively, a difference not considered clinically meaningful. Intentional weight loss was not associated with the precipitation of symptoms of depression, but instead appeared to protect against this occurrence. Mild (or greater) symptoms of depression at baseline did not prevent overweight/obese individuals with type 2 diabetes from achieving significant weight loss.

Two questions frequently arise when considering whether depressed, obese individuals should undertake weight reduction. The first is whether dieting and weight reduction precipitate (or exacerbate) symptoms of depression (1–3). The second question is whether individuals with mild or greater symptoms of depression can achieve the same magnitude of weight loss as obese individuals without any symptoms of depression (4,5).

The concern that weight loss may precipitate symptoms of depression arose from a study of normal weight volunteers who lost nearly 25% of their body weight and subsequently experienced adverse emotional reactions, including clinically significant depression (1). Some investigators believe that dieting and weight loss have similar ill effects in overweight/obese individuals (6,7), although studies of weight loss achieved with behavioral treatments have revealed reductions, rather than increases, in symptoms of depression (8–10). With one exception (11), previous studies have been limited by small samples and by the failure to examine the incidence (and resolution) of symptoms of depression. In addition, prior studies typically have not included a control group of non-dieting individuals against which to judge changes in mood observed in individuals assigned to lose weight.

Lack of motivation and concentration, two cardinal features of depression, could undermine efforts to adhere to rigorous diet and activity recommendations, and several studies have shown depression to be a predictor of attrition from weight loss programs (12,13). Studies of whether pretreatment symptoms of depression impede weight loss have yielded mixed results. Several investigations found no relationship between these two variables (5,13,14), while others observed smaller weight losses in patients with greater pretreatment symptoms of depression (4,15,16). All of these studies were limited by small sample sizes and by relatively low levels of baseline depression, the latter occurrence resulting from investigators’ tendency to exclude depressed individuals from weight loss trials (17–21).

In the present investigation, we used data from the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study to: 1) assess the effects of dieting and weight loss on the precipitation (and possible resolution) of symptoms of depression; and 2) examine whether individuals with symptoms of depression at baseline would lose less weight than individuals with no symptoms of depression. Look AHEAD is examining the long-term effects on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality of an Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI), compared with a usual care group, referred to as Diabetes Support and Education (DSE), in 5145 overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. The fact that overweight individuals with type 2 diabetes are known to be at increased risk of depression (22,23) makes this an excellent sample with which to address the questions outlined above. At the end of the first year of treatment, weight losses for the ILI and DSE groups were 8.6% and 0.7%, respectively (24). In addition, health-related quality of life (which included assessment of symptoms of depression) improved more in the ILI than DSE groups (25). Using this data set, we compared the incidence (as well as resolution) of symptoms of depression in the ILI and DSE groups. Given the generally favorable effects of weight loss on mood, we hypothesized that the ILI group would show a smaller incidence of symptoms of depression than those in DSE. We included an examination of suicidal ideation, given recent concerns that weight loss achieved with weight loss medications (e.g., rimonabant) may precipitate suicidal behavior (26,27). Finally, we hypothesized that individuals in the ILI and DSE groups, who reported symptoms of depression at baseline, would achieve smaller weight losses at 1 year than would those who were free of such symptoms.

Methods

Participants

The Look AHEAD study design and participants have been described in detail previously (28). In summary, overweight/obese individuals with type 2 diabetes were recruited from 16 clinical centers in the United States. Participants were 45–76 years old and had a body mass index (BMI) ≥27 kg/m2 (or ≥25 kg/m2 if on insulin). Individuals with inadequate diabetes control (i.e., HbA1c >11%), or with conditions likely to affect treatment adherence, safety, or retention, were excluded from the trial. Individuals diagnosed with psychosis or bipolar disorder, or who had been hospitalized for depression in the past 6 months, also were excluded. All participants provided informed consent, as approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board.

The present analysis was based on 5129 participants who enrolled in the study and completed baseline assessments of weight and mood. Baseline demographic information is provided in Table 1. Sixty-three percent of the sample was self-identified as non-Hispanic White, 16% as African American, 13% Hispanic, 5% American Indian, and 1% as Asian/Pacific Islander. Forty percent of participants were male.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all participants (N = 5129), and by depression status at baseline (as determined by BDI score).

| Variable | Overall | BDI < 10 | BDI ≥ 10 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | N=5129 | N=4244 | N=885 | 0.022 |

| 45 – 55 | 1620 (31.6) | 1302 (30.7) | 318 (35.9) | |

| 56 – 65 | 2638 (51.4) | 2187 (51.5) | 451 (51.0) | |

| 66 – 76 | 871 (17.0) | 755 (17.8) | 116 (13.1) | |

| Gender | N=5129 | N=4244 | N=885 | <.001 |

| Female | 3050 (59.5) | 2433 (57.3) | 617 (69.7) | |

| Male | 2079 (40.5) | 1811 (42.7) | 268 (30.3) | |

| Race | N=5128 | N=4243 | N=885 | 0.014 |

| African American / Black (not Hispanic) | 800 (15.6) | 645 (15.2) | 155 (17.5) | |

| American Indian / Native American / Alaskan Native | 257 (5.0) | 180 (4.2) | 77 (8.7) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 50 (1.0) | 40 (0.9) | 10 (1.1) | |

| Hispanic | 680 (13.3) | 523 (12.3) | 157 (17.7) | |

| Other/Mixed | 100 (2.0) | 83 (2.0) | 17 (1.9) | |

| White | 3241 (63.2) | 2772 (65.3) | 469 (53.0) | |

| Years of education | N=5018 | N=4155 | N=863 | <.001 |

| 13 – 16 years | 1911 (38.1) | 1540 (37.1) | 371 (43.0) | |

| < 13 years | 1021 (20.3) | 783 (18.8) | 238 (27.6) | |

| > 16 years | 2086 (41.6) | 1832 (44.1) | 254 (29.4) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | N=5129 | N=4244 | N=885 | <.001 |

| 25 – 27 | 118 (2.3) | 93 (2.2) | 25 (2.8) | |

| 27 – 30 | 645 (12.6) | 564 (13.3) | 81 (9.2) | |

| 30 – 35 | 1811 (35.3) | 1543 (36.4) | 268 (30.3) | |

| 35 – 40 | 1408 (27.5) | 1139 (26.8) | 269 (30.4) | |

| >= 40 | 1147 (22.4) | 905 (21.3) | 242 (27.3) | |

| BED status | N=5105 | N=4231 | N=874 | <.001 |

| No | 4453 (87.2) | 3787 (89.5) | 666 (76.2) | |

| Yes | 652 (12.8) | 444 (10.5) | 208 (23.8) | |

| General health score | 47.2±8.9 | 48.5±8.2 | 40.6±9.2 | <.001 |

| Diabetes duration | 6.8±6.5 | 6.7±6.5 | 7.2±6.8 | 0.138 |

Numbers (and percentages within each category) of participants are presented. For general health score and diabetes duration variables, means (± SD) are presented. P values indicate whether there were significant differences between participants with a BDI score <10, compared with ≥10. BED = binge eating disorder; BMI = body mass index.

Intervention

Participants were randomly assigned to ILI or DSE, both of which have been described previously (24,29). The ILI, modeled after the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP)’s Lifestyle Balance intervention (30), sought to induce a mean weight loss ≥7% of initial weight and to increase physical activity to ≥175 minutes a week. Participants received intensive behaviorally-oriented diet and physical activity counseling during the first year. They were provided three group and one individual meeting(s) each month during months 1–6, and two group and one individual session(s) per month during months 7–12. Participants were instructed to consume a diet of 1200–1800 kcal/d (based on body weight) which, during the first 4 months, included replacing two meals and one snack per day with liquid shakes and meal bars. Participants in the DSE group were offered three group meetings during the year and were given educational information on nutrition, physical activity, and social support.

Dependent Measures

Demographics and anthropometric characteristics

Weight was measured at baseline and 1 year (by assessors masked to treatment condition) using a digital scale (Tanita, Willowbrook, IL, model BWB-800). Height was measured at baseline using a wall-mounted stadiometer.

Mood and suicidal ideation

Symptoms of depression were assessed at baseline and 1 year using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (31), a 21-item questionnaire that assesses mood over the previous 2 weeks. This instrument is an effective screening tool for major depression in diabetic patients (32). Total scores range from 0–63, with higher values indicating greater symptoms of depression. In the present study, however, item # 19, which assesses recent weight loss, was excluded from analysis because participants were overweight/obese and were required to be weight stable at entry. Thus, our use of the inventory yielded scores of 0–60. Scores of 0–9 reflect minimal (i.e., subclinical) symptoms, whereas values of 10–18, 19–29, and ≥30 indicate mild, moderate, and severe symptoms of depression, respectively (33). Participants who endorsed current symptoms of depression (i.e., scores ≥10 on the BDI) were classified as reporting mild or greater symptoms of depression, regardless of whether they were taking anti-depressant medication.

Item #9 on the BDI assesses suicidal ideation, as judged by the following responses: (a) “I do not have any thoughts of killing myself;" (b) "I have thoughts of killing myself, but I would not carry them out;" (c) "I would like to kill myself;" and, (d) "I would kill myself if I had the chance.” For the purpose of this study, respondents who endorsed options b, c, or d were deemed to have suicidal ideation.

Binge eating

Binge eating behavior was assessed by self-report using items from the Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns (34). Participants were classified as having binge eating behavior if in the past 6 months they reported one or more episodes of eating a large amount of food in a discrete period of time, experienced a sense of loss of control during that eating episode, and denied use of any compensatory behaviors (such as purging or excessive exercise).

General health and diabetes duration

The Medical Outcomes Study, 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36), version 2, was used at baseline to assess general health. The SF-36 is a well-validated measure of health-related quality of life (35). At baseline, participants also indicated the number of years since being diagnosed with diabetes.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Mean values (± standard deviation) are reported. Differences in demographic variables between participants with symptoms of depression (BDI ≥10) and those without symptoms were compared using linear regression models (with gender and clinical site as covariates) for continuous variables. Generalized linear models with a multivariate distribution were used for categorical variables.

In order to examine incidence and resolution of symptoms of depression after 1 year of treatment, we classified each of the ILI and DSE participants into the following four categories based on a BDI score of 10 or above: 1) participants with minimal symptoms of depression at baseline and also minimal symptoms at 1 year; 2) individuals with minimal symptoms at baseline but who endorsed mild or greater symptoms of depression at 1 year; 3) participants who reported mild or greater symptoms of depression at baseline but denied symptoms at 1 year; and 4) individuals who reported mild or greater symptoms of depression at baseline and also at 1 year. The percentages of participants in each group who met criteria for inclusion in each category were compared using chi-squared tests.

Differences in changes in symptoms of depression (continuous scores on the BDI) between participants with and without symptoms of depression at baseline, and between ILI and DSE groups, were compared using a 2-way ANOVA, controlling for the baseline weight, BDI score, gender, age, race, years of education, BED status, general health score and clinical site. In order to determine the effects of baseline symptoms of depression, 1-year symptoms of depression, and treatment group on weight loss at 1 year, a 2 × 2 × 2 (baseline symptoms of depression by 1-year symptoms of depression by treatment group) ANOVA was conducted.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Demographic characteristics for participants with and without symptoms of depression are presented in Table 1. Participants with BDI scores ≥10 at baseline were significantly younger, reported fewer years of education, and were more likely to be female and to be non-White than those with scores < 10. They also had a significantly higher BMI, were more likely to report bingeing behavior, and reported poorer general health scores than participants without symptoms of depression. No differences in diabetes duration were found between participants with and without symptoms of depression.

Mean BDI scores for participants by treatment group and depression status are presented in Table 2. The numbers (and percentages) of participants reporting minimal, mild, moderate and severe symptoms of depression at baseline and 1 year are depicted in Table 3. There were no significant differences between ILI and DSE in the percentages of participants with symptoms of depression at baseline (17.9% vs. 16.6%) or in the number of cases of suicidal ideation (SI: 2.9% vs. 2.1%, respectively). All participants with SI endorsed the statement, "I have thoughts of killing myself, but I would not carry them out." No one reported the more serious options, indicating desire or intent to kill themselves. Across the whole sample, significantly more participants with a BDI score ≥10 (i.e., with mild or greater symptoms of depression) endorsed suicidal ideation at baseline than among those with a score <10 (i.e., minimal symptoms of depression) (11.1% vs. 0.7%, RR = 15.8, 95% CI = 10.6, 23.1; P<0.001).

Table 2.

Mean (± SD) baseline Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores for participants in the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) and Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) groups.

| N | Mean (± SD) BDI Score |

Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILI | All | 2563 | 5.5 ± 5.2 | 0–35 |

| With symptoms of depression | 459 | 14.4 ± 4.5 | 10–35 | |

| No symptoms of depression | 2104 | 3.6 ± 2.7 | 0–9 | |

| DSE | All | 2566 | 5.4 ± 4.7 | 0–29 |

| With symptoms of depression | 426 | 13.5 ± 3.7 | 10–29 | |

| No symptoms of depression | 2140 | 3.8 ± 2.8 | 0–9 | |

| All | With symptoms of depression | 885 | 14.0 ± 4.1 | 10–35 |

| No symptoms of depression | 4244 | 3.7 ± 2.8 | 0–9 |

Table 3.

Numbers (and percentages) of participants with Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores indicating minimal, mild, moderate, and severe symptoms of depression, respectively, at baseline and 1 year in the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) and Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) groups.

| Baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI category (score range) | ILI | DSE | Overall | ||||

| Minimal | (0–9) | 2104 | (82.1%) | 2140 | (83.4%) | 4244 | (82.8%) |

| Mild | (10–18) | 387 | (15.1%) | 386 | (15.0%) | 773 | (15.1%) |

| Moderate | (19–29) | 67 | (2.6%) | 40 | (1.6%) | 107 | (2.1%) |

| Severe | (30+) | 5 | (0.2%) | 0 | (0.0%) | 5 | (0.1%) |

| Overall | 2563 | (100%) | 2566 | (100%) | 5129 | (100%) | |

| Year 1 | |||||||

| BDI category (score range) | ILI | DSE | Overall | ||||

| Minimal | (0–9) | 2139 | (83.5%) | 2012 | (78.4%) | 4151 | (80.9%) |

| Mild | (10–18) | 246 | (9.6%) | 303 | (11.8%) | 549 | (10.7%) |

| Moderate | (19–29) | 36 | (1.4%) | 54 | (2.1%) | 90 | (1.8%) |

| Severe | (30+) | 9 | (0.4%) | 3 | (0.1%) | 12 | (0.2%) |

| Overall* | 2563 | (100%) | 2566 | (100%) | 5129 | (100%) | |

At 1 year, 133 participants in the ILI group, and 194 participants in the DSE group (327 total), had missing BDI values.

Non-completers

Of the 5129 participants, 327 did not complete BDIs at 1 year, yielding a sample of 4802 for the incidence study. Non-completers had a higher baseline BDI score than participants who completed the 1-year assessment (6.6±5.8 vs. 5.4±4.8, respectively, (P<0.001, effect size = 0.24), with mean scores for both groups indicating minimal symptoms of depression. Within the ILI, 30.8% (41/133) of non-completers reported mild or greater symptoms of depression, compared with 22.2% (43/194) in DSE (ns). Among participants who completed the 1-year assessment, 16.7% (801/4802) reported symptoms of depression at baseline, compared to 83.3% (4001/4802) who reported no symptoms (P<0.001). No other baseline differences were observed between participants who did and did not complete the 1 year assessment.

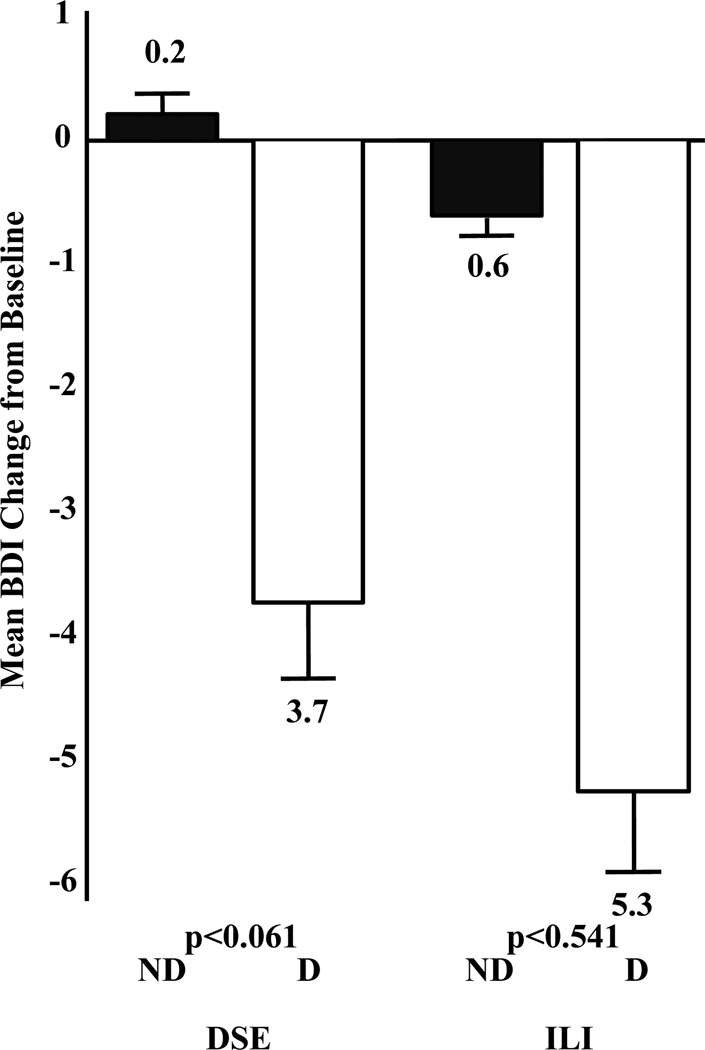

Changes in BDI Scores at 1 Year

Changes in BDI scores for participants in ILI and DSE who did and did not report symptoms of depression at baseline are shown in Figure 1. Participants in ILI showed a mean reduction in BDI score of 1.4±4.7 vs. 0.4±4.5 points for the DSE group. The ANOVA showed significant main effects on BDI score change of treatment group (P<0.001, effect size = 0.27) and baseline depression (P<0.001, effect size = 0.99), as well as a significant interaction (P<0.035). As shown in Figure 1, participants within the ILI who reported baseline symptoms of depression showed a decline of 5.3±6.8 points on the BDI at 1 year, compared with a decline of 0.6±3.7 points for individuals reporting no symptoms of depression. Participants with mild or greater symptoms of depression in DSE showed a reduction of 3.7±6.2 points on the BDI, compared to an increase of 0.2±3.8 points on the BDI for participants with minimal symptoms.

Figure 1.

Change in Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score (± SEM) at 1 Year in Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) and Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) groups by depression status at baseline. D = participants who reported symptoms of depression at baseline; ND = participants with no/minimal symptoms reported at baseline. Mean (±SD) baseline BDI scores were as follows: ILI-ND 3.6 ± 2.7; ILI-D 14.4 ± 4.5; DSE-ND: 3.8 ± 2.8; DSE-D: 13.5 ± 3.7. Symptoms of depression declined significantly more (P<0.001) in the ILI than DSE group, and there was a significant (P<0.035) depression status by treatment group interaction.

Incidence and Resolution of Depression at 1 Year

Table 4 shows frequencies of participants who acknowledged mild or greater symptoms of depression (BDI≥10) at baseline and 1-year. At the end of the year, 6.3% of ILI participants who did not report symptoms at baseline reported the onset of symptoms of depression (i.e., incident depression), which was significantly (RR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.5, 0.8; P<0.001) lower than the 9.6% observed in the DSE group. (The lower incidence of symptoms of depression in the ILI group remained statistically significant when the incidence of antidepressant medication use in ILI and DSE [4.3% vs. 2.7%, respectively] was controlled for (RR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.5, 0.8, p<0.001).) A logistic regression analysis showed that being assigned to DSE significantly increased the odds of reporting symptoms of depression at 1 year (OR = 1.62, 95% CI =1.3, 2.1; P<0.001). There were no significant differences between ILI and DSE groups, however, in the numbers of participants who showed resolution of their symptoms of depression; 60.8% and 55.6% of ILI and DSE participants, respectively, reported symptoms of depression at baseline but not at 1 year (P=0.140).

Table 4.

Changes in depression status at 1 year, and corresponding changes in weight and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score, for participants in the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) and Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) groups.

| ILI | DSE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | % Weight Loss at 1 Yr |

BDI change at 1 Yr |

N (%) | % Weight Loss at 1 Yr |

BDI change at 1 Yr |

|

| No symptoms of depression at baseline | 2012 (100) | 1989 (100) | ||||

| Symptoms at 1 year (Incident) |

127 (6.3) | −4.6 ± 6.5 | +7.5 ± 5.0 | 190 (9.6) | −0.7 ± 5.2 | +7.3 ± 5.2 |

| No symptoms at 1 year (No symptoms at either time) |

1885 (93.7) | −9.0 ± 6.8 | −1.2 ± 2.8 | 1799 (90.4) | −0.7 ± 4.6 | −0.5 ± 2.8 |

| Symptoms of depression at baseline | 418 (100) | 383 (100) | ||||

| Symptoms of depression at 1 year (Maintenance) |

164 (39.2) | −6.2 ± 6.0 | −0.2 ± 7.0 | 170 (44.4) | +0.4 ± 4.7 | +0.7 ± 5.1 |

| No symptoms at 1 year (Resolution) |

254 (60.8) | −9.0 ± 6.9 | −8.5 ± 4.2 | 213 (55.6) | −1.0 ± 5.1 | −7.3 ± 4.4 |

Note: Incident depression is shown by persons who reported minimal symptoms of depression at baseline but reported mild or greater symptoms by 1 year. Resolution of depression is shown by persons who reported mild or greater symptoms of depression at baseline but reported minimal symptoms at 1 year. Negative numbers indicate decreases in weight or BDI score.

The mean BDI score for individuals who reported incident symptoms of depression was 5.8 ± 2.6 at baseline, compared to 13.2 ± 4.4 at 1 year, yielding a mean increase of 7.4 points on the BDI.

Incidence and Resolution of Suicidal Ideation

Incident suicidal ideation was observed in approximately 1.4% of participants in the ILI group and 1.9% of participants in the DSE group; these participants denied thoughts of suicide at baseline but endorsed their occurrence at 1 year (P=0.266, Table 4). There were no significant differences in the number of participants in ILI and DSE who showed resolution of suicidal ideation at 1 year (68.2% vs. 72.0%, P=0.657).

Baseline Depression and Changes in Weight at 1 Year

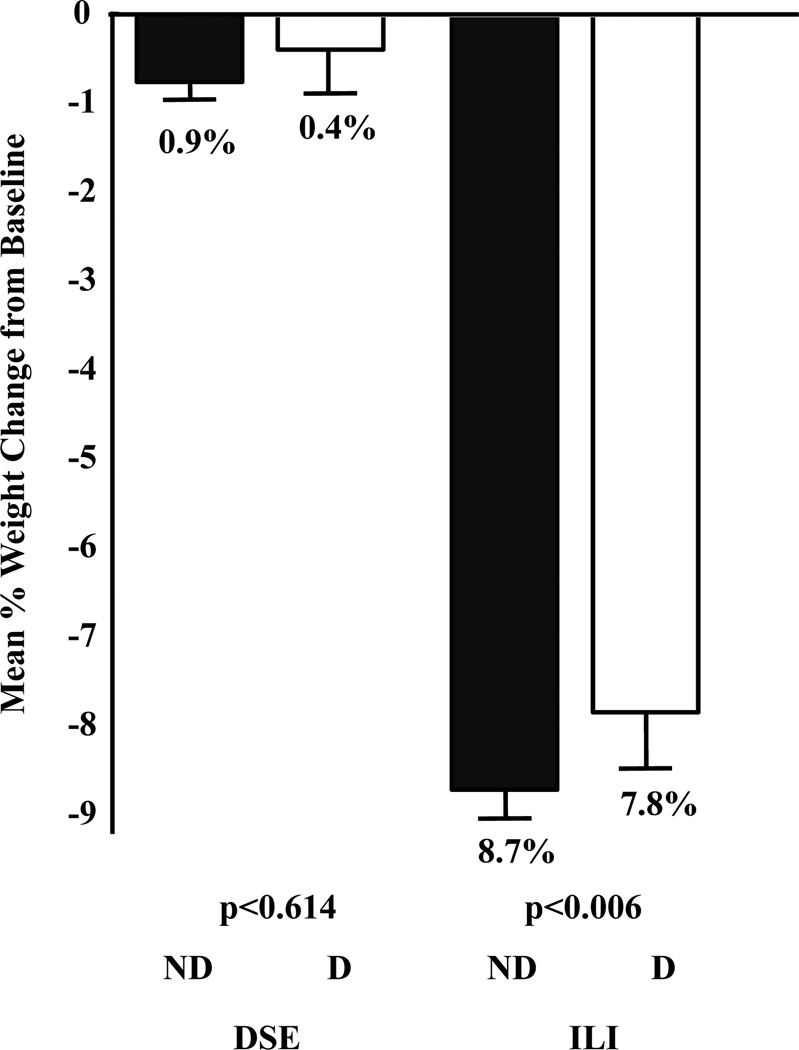

As reported previously, the ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of weight loss on treatment group (P<0.001, effect size = −1.23), with mean losses of 8.6±6.9 and 0.7±4.8% for ILI and DSE, respectively. A significant main effect of baseline symptoms of depression also was observed (P=0.009, effect size = 0.10); participants with mild or greater symptoms of depression lost 4.3±7.0%, compared with 4.8±7.1% for those with minimal symptoms. The treatment group by depression status interaction was not significant (P=0.110). As shown in Figure 2, within the ILI group, participants with minimal vs. mild or greater symptoms of depression lost 7.8±6.7% and 8.7±6.9%, respectively, with corresponding losses in the DSE group of 0.4±5.0% and 0.7±4.7%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Mean percent (± SEM) of initial weight lost at 1 Year in Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) and Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) groups by depression status at baseline. D = participants who reported mild or greater symptoms of depression at baseline; ND = participants with no/minimal symptoms reported at baseline. A 2 × 2 ANOVA (i.e., treatment-group by depression-status) revealed that ILI participants lost significantly (P<0.001) more weight than DSE participants and that participants considered free of symptoms of depression at baseline lost significantly (P<0.009) more weight than those who reported mild or greater symptoms of depression. The treatment group by depression status interaction was not significant (P=0.110).

Changes in Mood Category and Weight at 1 Year

Changes in weight for participants who showed incidence, resolution or maintenance of symptoms of depression are shown in Table 4. The ANOVA revealed a significant (P=0.006) 3-way interaction between baseline depression status, 1 year depression status, and treatment group. Participants in ILI (n=127) without symptoms of depression at baseline, but who developed mild or greater symptoms of depression during the year (i.e., incident), lost 4.6±6.4% of initial body weight. This was significantly (P<0.001, effect size = 0.65) less than the 9.0±6.9% lost by participants who showed resolution of their symptoms of depression (n=254) and less than (P<0.001, effect size = 0.65) the 9.0±6.8% lost by those who reported minimal symptoms of depression at either baseline or at 1 year (i.e., no symptoms of depression at either time point, n=1885). ILI participants who both started and ended the study with a BDI score ≥10 (i.e., maintained symptoms of depression, n=164) lost 6.2±6.0% of initial weight, which was significantly less than the weight lost by participants who showed resolution (p<0.001, effect size = 0.42), or who reported no symptoms of depression at either time point (P<0.001, effect size = 0.42), but was not significantly different from participants who showed incident symptoms of depression (P>0.05).

Participants in the DSE group who showed incident symptoms of depression (n=190) lost 0.7±5.2% of initial weight, while those who showed no symptoms of depression at either baseline or at 1 year (n=1799) lost 0.7±4.6%, and those who showed resolution of their depression (n=213) lost 1.0±5.1%. Participants who both started and ended the study with a BDI score ≥10 (i.e., maintained, n=170) gained 0.4±4.7% of their initial weight. Participants in DSE who maintained symptoms of depression lost significantly less weight than those who showed resolution of their symptoms of depression (P=0.003, effect size = 0.31), those who showed no symptoms of depression at either baseline or at 1 year (P=0.002, effect size = 0.25), and participants who showed incident symptoms of depression at year 1 (P=0.017, effect size = 0.25). There were no other statistically significant differences among the other three groups.

Psychiatric Adverse Events

Adverse psychiatric events were reported on an ad hoc basis. During the year, five participants reported an adverse event involving depression; three of these cases were in the ILI group and two were in the DSE group. None of these events involved suicidal behavior. Of these five participants, none reported symptoms of depression at baseline (defined by BDI ≥10), but three participants reported use of anti-depressant medication at baseline.

Discussion

This is the first randomized controlled trial of which we are aware to examine precipitation and resolution of symptoms of depression in individuals who received a lifestyle modification weight loss intervention, compared with participants in a non-dieting control group. At 1 year, participants in the ILI lost a mean of 8.6% of their initial weight, compared to 0.7% for those in DSE (24), and reported significantly greater improvements in symptoms of depression compared with DSE participants (1.4 vs. 0.4 points) (25). Participants in ILI with baseline BDI scores ≥10 showed an even larger reduction of 5.3 points, compared to 0.6 for those without baseline symptoms of depression. These findings suggest that moderate weight loss in patients with mild to moderate symptoms of depression is associated with improvements, not worsening, in mood.

In the current study, we observed a significantly lower number of incident cases of symptoms of depression in the ILI group at 1 year than in the DSE group (6.3% vs. 9.6%), which remained significant after controlling for incident use of anti-depressant medications in the two groups. Individuals who reported incident symptoms of depression reported a mean increase of >7 points on the BDI, which is regarded as a clinically significant change by experts (36). These results counter the notion that intentional dieting, with its resulting weight loss, precipitates depression in overweight or obese individuals. Furthermore, the incidence of suicidal ideation at 1 year was not significantly different between participants in the ILI and DSE groups (1.4% vs. 1.9%), suggesting that moderate weight loss resulting from lifestyle change does not precipitate suicidal thoughts in this population.

The DSE group provides useful information about changes in mood that can be expected in overweight persons (with type 2 diabetes) who are not in a weight loss program. As a group, DSE participants who reported mild or greater symptoms of depression at baseline showed improvements in mood at 1 year (as indicated by a 3.7 point decline on the BDI). As noted, 9.6% of participants reported the onset of clinically significant symptoms of depression during the year, whereas 55.6% of those with symptoms of depression at baseline experienced remission of this condition (i.e., BDI <10). These results indicate that mood was subject to fluctuation over the course of a year in a sample of overweight individuals who were not instructed to lose weight and who remained relatively weight stable. Similar fluctuations in symptoms of depression, as well as in the use of anti-depressant medications, were reported over time in participants in the Diabetes Prevention Program (11). Such results set the bar by which to compare changes in mood associated with various weight loss interventions, including behavioral and pharmacologic approaches. The greater reduction in BDI scores observed in individuals reporting symptoms of depression at baseline in the ILI group (−5.3) versus the DSE group (−3.7) suggests that the behavioral weight loss program augmented the spontaneous improvements in mood that were observed in the DSE group at 1 year.

The second aim of our study was to examine whether individuals who reported symptoms of depression at baseline would lose less weight than those without such symptoms. Collapsing across the ILI and DSE groups, participants with mild or greater symptoms of depression at baseline lost significantly less weight than individuals with no symptoms of depression (4.3% vs 4.8%), but the difference cannot be considered clinically meaningful. Similarly, the difference in mean weight loss between participants with and without symptoms of depression in the ILI (7.8% vs 8.7%) is not clinically meaningful. Thus, our results do not support the routine exclusion of participants with symptoms of depression from weight loss trials (17,18,37–39) based on the belief that they may lose less weight than non-depressed individuals. Rather, these findings indicate that individuals with mild or greater symptoms of depression who enroll in a supervised weight reduction program are able to lose clinically significant amounts of weight and achieve improvements (rather than worsening) in mood. We tentatively conclude that such individuals can be safely encouraged to lose weight and should not be routinely excluded from weight loss trials, as currently practiced.

While the presence of pre-treatment symptoms of depression does not appear to substantially hamper weight loss, the onset of symptoms of depression may impede weight loss. ILI individuals who developed symptoms of depression during the year (i.e., cases of incident symptoms of depression) lost significantly less weight (4.6%) than those who resolved (9.0%), or did not report symptoms of depression at either time point (9.0%), and nominally less than those who maintained symptoms of depression (6.2%). Thus, it appears that the presence of mild or greater symptoms of depression at baseline is not a good predictor of weight loss in a clinical trial; rather the presence of symptoms of depression at the end of treatment (regardless of whether they were present at baseline) may indicate poorer outcomes, with the poorest for those who show incident symptoms of depression. This finding is similar to that obtained recently by Gorin et al. (40), who determined that the presence of binge-eating behavior in Look AHEAD participants at baseline alone did not predict poor weight loss outcomes. Instead, weight loss was poorest in those participants who either developed bingeing behavior during the study or did not resolve their pre-existing binge-eating behavior. The present study was not designed to assess causality; thus, we cannot determine definitively whether individuals who reported incident symptoms of depression lost less weight because they developed symptoms of depression, or whether symptoms of depression developed in response to achieving a smaller-than-desired weight loss (or even partial regain of initial weight loss in year 1). Further studies that include more frequent assessment of both mood and weight are needed to identify the nature of the relationship between these two variables.

We observed comparable attrition rates between individuals with and without symptoms of depression, contrary to suggestions that depressed individuals are less likely to complete weight loss trials than their non-depressed counterparts. Across the sample, of the 4802 individuals who completed the 1-year assessment, only 16.7% reported symptoms of depression at baseline, compared to 83.3% who reported no symptoms. There was no significant difference in the number of non-completers who reported mild or greater symptoms of depression at baseline in the ILI vs. DSE groups (30.8% vs. 22.2%, ns), indicating that the intensive lifestyle intervention did not increase the likelihood of individuals with baseline symptoms of depression dropping out of the study.

The prevalence of suicidal ideation, as assessed by a single item on the BDI, was very low at baseline; only 129 of 5129 participants (2.5%) endorsed passive suicidal thoughts. These individuals were more likely to report mild or greater symptoms of depression at baseline; one of every 10 participants with symptoms of depression at baseline acknowledged SI at baseline. The incident rate of suicidal ideation was very low and was independent of treatment group (1.4% vs. 1.9% for ILI and DSE, respectively). Some have argued that the higher rates of SI (and symptoms of depression) associated with some weight loss medications may be attributable to the effects of the greater weight loss induced by the medication (as compared with placebo), rather than to a possible direct effect of the medication on psychiatric function. Our results suggest that greater weight loss alone, as achieved by the ILI vs. DSE, is not associated with increased SI or symptoms of depression.

Strengths of the present study include the large and ethnically diverse sample, and the inclusion of the DSE group that provided an estimate of spontaneous changes in mood over the course of the year in the absence of intentional dieting and weight loss. Significant limitations of the current study include its reliance on the Beck Depression Inventory (a self-report questionnaire) as the primary assessment of mood, as well as the low level of symptoms of depression in the sample, reflective of the extensive screening process in which those who were deemed unfit to complete the study were excluded from the trial. Future studies should incorporate structured clinical interviews and formal assessments of depression and suicidal ideation at baseline and at several times over the course of treatment. This is the Food and Drug Administration’s current requirement for the assessment of new weight loss medications that act upon the central nervous system (41). More frequent assessments of weight and mood would allow determination of whether improvements in symptoms of depression precede weight loss or are a consequence of weight reduction.

In summary, the present findings suggest that overweight and obese individuals with mild or greater symptoms of depression can successfully participate in a behavioral weight loss program and should be encouraged to do so. Further research is needed to assess the effect of such treatment in obese individuals who suffer from severe depression.

Acknowledgements

Michael Walkup, M.S. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding and Support

This study is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Office of Research on Women’s Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01066); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR0021140); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (M01RR000056 44) and NIH grant (DK 046204); and the University of Washington/VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346). The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: Federal Express; Health Management Resources; Johnson & Johnson, LifeScan Inc.; Optifast-Novartis Nutrition; Roche Pharmaceuticals; Ross Product Division of Abbott Laboratories; Slim-Fast Foods Company; and Unilever.

This report was prepared by the authors on behalf of the Look AHEAD Research Group. Members of the research group who participated in the recruitment, assessment, treatment, and retention of participants during the first year of the study are shown below:

Clinical Sites

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions: Frederick L. Brancati, MD, MHS (Principal Investigator); Jeff Honas, MS (Program Coordinator); Lawrence Cheskin, MD (Co-investigator); Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH (Co-investigator); Kerry Stewart, EdD (Co-investigator); Richard Rubin, PhD (Co-investigator); Jeanne Charleston, RN; Kathy Horak, RD.

Pennington Biomedical Research Center: George A. Bray, MD (Principal Investigator); Kristi Rau (Program Coordinator); Allison Strate, RN (Program Coordinator); Brandi Armand, LPN (Program Coordinator); Frank L. Greenway, MD (Co-investigator); Donna H. Ryan, MD (Co-investigator);

Donald Williamson, PhD (Co-investigator); Amy Bachand; Michelle Begnaud; Betsy Berhard; Elizabeth Caderette; Barbara Cerniauskas; David Creel; Diane Crow; Helen Guay; Nancy Kora; Kelly LaFleur; Kim Landry; Missy Lingle; Jennifer Perault; Mandy Shipp, RD; Marisa Smith; Elizabeth Tucker.

The University of Alabama at Birmingham: Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH (Principal Investigator); Sheikilya Thomas MPH (Program Coordinator); Monika Safford, MD (Co-investigator); Vicki DiLillo, PhD; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Amy Dobelstein; Stacey Gilbert, MPH; Stephen Glasser, MD; Sara Hannum, MA; Anne Hubbell, MS; Jennifer Jones, MA; DeLavallade Lee; Ruth Luketic, MA, MBA, MPH; Karen Marshall; L. Christie Oden; Janet Raines, MS; Cathy Roche, RN, BSN; Janet Truman; Nita Webb, MA; Audrey Wrenn, MAEd.

Harvard Center: Massachusetts General Hospital. David M. Nathan, MD (Principal Investigator); Heather Turgeon, RN, BS, CDE (Program Coordinator); Kristina Schumann, BA (Program Coordinator); Enrico Cagliero, MD (Co-investigator); Linda Delahanty, MS, RD (Co-investigator);

Kathryn Hayward, MD (Co-investigator); Ellen Anderson, MS, RD (Co-investigator); Laurie Bissett, MS, RD; Richard Ginsburg, PhD; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD; Virginia Harlan, MSW; Charles McKitrick, RN, BSN, CDE; Alan McNamara, BS; Theresa Michel, DPT, DSc CCS; Alexi Poulos, BA; Barbara Steiner, EdM; Joclyn Tosch, BA.

Joslin Diabetes Center. Edward S. Horton, MD (Principal Investigator); Sharon D. Jackson, MS, RD, CDE (Program Coordinator); Osama Hamdy, MD, PhD (Co-investigator); A. Enrique Caballero, MD (Co-investigator); Sarah Bain, BS; Elizabeth Bovaird, BSN, RN; Ann Goebel-Fabbri, PhD; Lori Lambert, MS, RD; Sarah Ledbury, MEd, RD; Maureen Malloy, BS; Kerry Ovalle, MS, RCEP, CDE.

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. George Blackburn, MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Christos Mantzoros, MD, DSc (Co-investigator); Kristinia Day, RD; Ann McNamara, RN.

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center: James O. Hill, PhD (Principal Investigator); Marsha Miller, MS, RD (Program Coordinator); JoAnn Phillipp, MS (Program Coordinator); Robert Schwartz, MD (Co-investigator); Brent Van Dorsten, PhD (Co-investigator); Judith Regensteiner, PhD (Co-investigator); Salma Benchekroun MS; Ligia Coelho, BS; Paulette Cohrs, RN, BSN; Elizabeth Daeninck, MS, RD; Amy Fields, MPH; Susan Green; April Hamilton, BS, CCRC; Jere Hamilton, BA; Eugene Leshchinskiy;Michael McDermott, MD; Lindsey Munkwitz, BS; Loretta Rome, TRS; Kristin Wallace, MPH; Terra Worley, BA.

Baylor College of Medicine: John P. Foreyt, PhD (Principal Investigator); Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD (Program Coordinator); Henry Pownall, PhD (Co-investigator); Ashok Balasubramanyam, MBBS (Co-investigator); Peter Jones, MD (Co-investigator); Michele Burrington, RD; Chu-Huang Chen, MD, PhD; Allyson Clark, RD; Molly Gee, MEd, RD; Sharon Griggs; Michelle Hamilton; Veronica Holley; Jayne Joseph, RD; Patricia Pace, RD: Julieta Palencia, RN; Olga Satterwhite, RD; Jennifer Schmidt; Devin Volding, LMSW; Carolyn White.

University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine: Mohammed F. Saad, MD (Principal Investigator); Siran Ghazarian Sengardi, MD (Program Coordinator); Ken C. Chiu, MD (Co-investigator); Medhat Botrous; Michelle Chan, BS; Kati Konersman, MA, RD, CDE; Magpuri Perpetua, RD.

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center: University of TennesseeEast. Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH (Principal Investigator); Carolyn Gresham, RN (Program Coordinator); Stephanie Connelly, MD, MPH (Co-investigator); Amy Brewer, RD, MS; Mace Coday, PhD; Lisa Jones, RN; Lynne Lichtermann, RN, BSN; Shirley Vosburg, RD, MPH; and J. Lee Taylor, MEd, MBA.

University of Tennessee Downtown. Abbas E. Kitabchi, PhD, MD (Principal Investigator); Helen Lambeth, RN, BSN (Program Coordinator); Debra Clark, LPN; Andrea Crisler, MT; Gracie Cunningham; Donna Green, RN; Debra Force, MS, RD, LDN; Robert Kores, PhD; Renate Rosenthal PhD; Elizabeth Smith, MS, RD, LDN; and Maria Sun, MS, RD, LDN; and Judith Soberman, MD (Co-investigator).

University of Minnesota: Robert W. Jeffery, PhD (Principal Investigator); Carolyn Thorson, CCRP (Program Coordinator); John P. Bantle, MD (Co-investigator); J. Bruce Redmon, MD (Co-investigator); Richard S. Crow, MD (Co-investigator); Scott Crow, MD (Co-investigator); Susan K Raatz, PhD, RD (Co-investigator); Kerrin Brelje, MPH, RD; Carolyne Campbell; Jeanne Carls, MEd; Tara Carmean-Mihm, BA; Emily Finch, MA; Anna Fox, MA; Elizabeth Hoelscher, MPH, RD, CHES; La Donna James; Vicki A. Maddy, BS, RD; Therese Ockenden, RN; Birgitta I. Rice, MS, RPh CHES; Tricia Skarphol, BS; Ann D. Tucker, BA; Mary Susan Voeller, BA; Cara Walcheck, BS, RD.

St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital Center: Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD (Principal Investigator); Jennifer Patricio, MS (Program Coordinator); Stanley Heshka, PhD (Co-investigator); Carmen Pal, MD (Co-investigator); Lynn Allen, MD; Diane Hirsch, RNC, MS, CDE; Mary Anne Holowaty, MS, CN.

University of Pennsylvania: Thomas A. Wadden, PhD (Principal Investigator); Barbara J. Maschak-Carey, MSN, CDE (Program Coordinator); Stanley Schwartz, MD (Co-investigator); Gary D. Foster, PhD (Co-investigator); Robert I. Berkowitz, MD (Co-investigator); Henry Glick, PhD (Co-investigator); Shiriki K. Kumanyika, PhD, RD, MPH (Co-investigator); Johanna Brock; Helen Chomentowski; Vicki Clark; Canice Crerand, PhD; Renee Davenport; Andrea Diamond, MS, RD; Anthony Fabricatore, PhD; Louise Hesson, MSN; Stephanie Krauthamer-Ewing, MPH; Robert Kuehnel, PhD; Patricia Lipschutz, MSN; Monica Mullen, MS, RD; Leslie Womble, PhD, MS; Nayyar Iqbal, MD.

University of Pittsburgh: David E. Kelley, MD (Principal Investigator); Jacqueline Wesche-Thobaben, RN, BSN, CDE (Program Coordinator); Lewis Kuller, MD, DrPH (Co-investigator); Andrea Kriska, PhD (Co-investigator); Janet Bonk, RN, MPH; Rebecca Danchenko, BS; Daniel Edmundowicz, MD (Co-investigator); Mary L. Klem, PhD, MLIS (Co-investigator); Monica E.Yamamoto, DrPH, RD, FADA (Co-investigator); Barb Elnyczky, MA; George A. Grove, MS; Pat Harper, MS, RD, LDN; Janet Krulia, RN, BSN, CDE; Juliet Mancino, MS, RD, CDE, LDN; Anne Mathews, MS, RD, LDN; Tracey Y. Murray, BS; Joan R. Ritchea; Jennifer Rush, MPH; Karen Vujevich, RN-BC, MSN, CRNP; Donna Wolf, MS.

The Miriam Hospital/Brown Medical School: Rena R. Wing, PhD (Principal Investigator); Renee Bright, MS (Program Coordinator); Vincent Pera, MD (Co-investigator); John Jakicic, PhD (Co-investigator); Deborah Tate, PhD (Co-investigator); Amy Gorin, PhD (Co-investigator); Kara Gallagher, PhD (Co-investigator); Amy Bach, PhD; Barbara Bancroft, RN, MS; Anna Bertorelli, MBA, RD; Richard Carey, BS; Tatum Charron, BS; Heather Chenot, MS; Kimberley Chula-Maguire, MS; Pamela Coward, MS, RD; Lisa Cronkite, BS; Julie Currin, MD; Maureen Daly, RN; Caitlin Egan, MS; Erica Ferguson, BS, RD; Linda Foss, MPH; Jennifer Gauvin, BS; Don Kieffer, PhD; Lauren Lessard, BS; Deborah Maier, MS; JP Massaro, BS; Tammy Monk, MS; Rob Nicholson, PhD; Erin Patterson, BS; Suzanne Phelan, PhD; Hollie Raynor, PhD, RD; Douglas Raynor, PhD; Natalie Robinson, MS, RD;Deborah Robles; Jane Tavares, BS.

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio: Steven M. Haffner, MD (Principal Investigator); Maria G. Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE (Program Coordinator); Carlos Lorenzo, MD (Co-investigator).

University of Washington/VA Puget Sound Health Care System: Steven Kahn MB, ChB (Principal Investigator); Brenda Montgomery, RN, MS, CDE (Program Coordinator); Robert Knopp, MD (Co-investigator); Edward Lipkin, MD (Co-investigator); Matthew L. Maciejewski, PhD (Co-investigator); Dace Trence, MD (Co-investigator); Terry Barrett, BS; Joli Bartell, BA; Diane Greenberg, PhD; Anne Murillo, BS; Betty Ann Richmond, MEd; April Thomas, MPH, RD.

Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix, Arizona and Shiprock, New Mexico: William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH (Principal Investigator); Paula Bolin, RN, MC (Program Coordinator); Tina Killean, BS (Program Coordinator); Cathy Manus, LPN (Co-investigator); Jonathan Krakoff, MD (Co-investigator); Jeffrey M. Curtis, MD, MPH (Co-investigator); Justin Glass, MD (Co-investigator); Sara Michaels, MD (Co-investigator); Peter H. Bennett, MB, FRCP (Co-investigator); Tina Morgan (Co-investigator); Shandiin Begay, MPH; Bernadita Fallis RN, RHIT, CCS; Jeanette Hermes, MS,RD; Diane F. Hollowbreast; Ruby Johnson; Maria Meacham, BSN, RN, CDE; Julie Nelson, RD; Carol Percy, RN; Patricia Poorthunder; Sandra Sangster; Nancy Scurlock, MSN, ANP-C, CDE; Leigh A. Shovestull, RD, CDE; Janelia Smiley; Katie Toledo, MS, LPC; Christina Tomchee, BA; Darryl Tonemah PhD.

University of Southern California: Anne Peters, MD (Principal Investigator); Valerie Ruelas, MSW, LCSW (Program Coordinator); Siran Ghazarian Sengardi, MD (Program Coordinator); Kathryn Graves, MPH, RD, CDE; Kati Konersman, MA, RD, CDE; Sara Serafin-Dokhan. Coordinating Center

Wake Forest University: Mark A. Espeland, PhD (Principal Investigator); Judy L. Bahnson, BA (Program Coordinator); Lynne Wagenknecht, DrPH (Co-investigator); David Reboussin, PhD (Co-investigator); W. Jack Rejeski, PhD (Co-investigator); Alain Bertoni, MD, MPH (Co-investigator); Wei Lang, PhD (Co-investigator); Gary Miller, PhD (Co-investigator); David Lefkowitz, MD (Co-investigator); Patrick S. Reynolds, MD (Co-investigator); Paul Ribisl, PhD (Co-investigator); Mara Vitolins, DrPH (Co-investigator); Michael Booth, MBA (Program Coordinator); Kathy M. Dotson, BA (Program Coordinator); Amelia Hodges, BS (Program Coordinator); Carrie C. Williams, BS (Program Coordinator); Jerry M. Barnes, MA; Patricia A. Feeney, MS; Jason Griffin, BS; Lea Harvin, BS; William Herman, MD, MPH; Patricia Hogan, MS; Sarah Jaramillo, MS; Mark King, BS; Kathy Lane, BS; Rebecca Neiberg, MS; Andrea Ruggiero, MS; Christian Speas, BS; Michael P. Walkup, MS; Karen Wall, AAS; Michelle Ward; Delia S. West, PhD; Terri Windham.

Federal Sponsors

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Barbara Harrison, MS; Van S. Hubbard, MD PhD; Susan Z. Yanovski, MD.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Lawton S. Cooper, MD, MPH;

Jeffrey Cutler, MD, MPH; Eva Obarzanek, PhD, MPH, RD.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Edward W. Gregg, PhD; David F. Williamson, PhD; Ping Zhang, PhD.

References

- 1.Keys A. Biology of human starvation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stunkard AJ. The dieting depression, incidence and clinical characteristics of untoward responses to weight reduction regimens. Am J Med. 1957;23:77–86. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(57)90359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaput JP, Arguin H, Gagnon C, Tremblay A. Increase in depression symptoms with weight loss: association with glucose homeostasis and thyroid function. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2008;33:86–92. doi: 10.1139/H07-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pagoto S, Bodenlos JS, Kantor L, Gitkind M, Curtin C, Ma Y. Association of major depression and binge eating disorder with weight loss in a clinical setting. Obesity. 2007;15:2557–2559. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludman E, Simon GE, Ichikawa LE, et al. Does depression reduce the effectiveness of behavioral weight loss treatment? Behav Med. 2010;35:126–134. doi: 10.1080/08964280903334527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McFarlane T, Polivy J, McCale RE. Help, not harm: psychological foundation for a nondieting approach toward health. J Soc Issues. 1999;55:261–276. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campos P. The Obesity Myth: Why America's Obsession with Weight is Hazardous to Your Health. New York: Gotham Books; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinkworth GD, Buckley JD, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Wilson CJ. Long-term effects of a very low-carbohydrate diet and a low-fat diet on mood and cognitive function. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1873–1880. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hainer V, Hlavata K, Gojova M, et al. Hormonal and psychobehavioral predictors of weight loss in response to a short-term weight reduction program in obese women. Physiol Res. 2008;57 Suppl 1:S17–S27. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadden TA, Foster GD, Letizia KA. One-year behavioral treatment of obesity: comparison of moderate and severe caloric restriction and the effects of weight maintenance therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:165–171. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubin RR, Knowler WC, Ma Y, et al. Depression symptoms and antidepressant medicine use in Diabetes Prevention Program participants. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:830–837. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark MM, Niaura R, King TK, Pera V. Depression, smoking, activity level, and health status: pretreatment predictors of attrition in obesity treatment. Addict Behav. 1996;21:509–513. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcus MD, Wing RR, Guare J, Blair EH, Jawad A. Lifetime prevalence of major depression and its effect on treatment outcome in obese type II diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:253–255. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faulconbridge LF, Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, et al. Changes in symptoms of depression with weight loss: results of a randomized trial. Obesity. 2009;17:1009–1016. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Levy RL, et al. Binge eating disorder, weight control self-efficacy, and depression in overweight men and women. Int J Obes. 2004;28:418–425. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeffery RW, Sherwood NE, Brelje K, et al. Mail and phone interventions for weight loss in a managed-care setting: Weigh-To-Be one-year outcomes. Int J Obes. 2003;27:1584–1592. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delahanty LM, Meigs JB, Hayden D, Williamson DA, Nathan DM. Psychological and behavioral correlates of baseline BMI in the diabetes prevention program (DPP) Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1992–1998. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.11.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finer N, James WP, Kopelman PG, Lean ME, Williams G. One-year treatment of obesity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study of orlistat, a gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor. Int J Obes. 2000;24:306–313. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tate DF, Wing RR, Winett RA. Using Internet technology to deliver a behavioral weight loss program. JAMA. 2001;285:1172–1177. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.9.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai AG, Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, et al. Metabolic syndrome and health-related quality of life in obese individuals seeking weight reduction. Obesity. 2008;16:59–63. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Sarwer DB, Prus-Wisniewski R, Steinberg C. Benefits of lifestyle modification in the pharmacologic treatment of obesity: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:218–227. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egede LE, Zheng D. Independent factors associated with major depressive disorder in a national sample of individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:104–111. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Look AHEAD Research Group. Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williamson DA, Rejeski J, Lang W, Van Dorsten B, Fabricatore AN, Toledo K. Impact of a weight management program on health-related quality of life in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:163–171. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Food and Drug Administration Advisory Committee. FDA Briefing Document: Zimulti (rimonabant) Tablets, 20mg. Rockville: FSA; 2007. [assessed Aug 6, 2007]. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen R, Kristensen PK, Bartels EM, Bliddal H, Astrup A. Efficacy and safety of the weight-loss drug rimonabant: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2007;370:1706–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD, et al. Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:610–628. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obesity. 2009;17:713–722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lustman PJ, Clouse RE, Griffith LS, Carney RM, Freedland KE. Screening for depression in diabetes using the Beck Depression Inventory. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:24–31. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199701000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck AT, Steer RA. In: Beck Depression Inventory Manual. Corporation TP, editor. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace & Company; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitzer RL, Yanovski S, Marcus MD. Binge Eating Disorder Clinical Interview. Pittsburgh, PA: Behavioral Measurement Database Services; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ. Sudden gains and critical sessions in cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:894–904. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rubin RR, Ma Y, Marrero DG, et al. Elevated depression symptoms, antidepressant medicine use risk of developing diabetes during the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:420–426. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, et al. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2111–2120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wirth A, Krause J. Long-term weight loss with sibutramine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286:1331–1339. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorin AA, Niemeier HM, Hogan P, et al. Binge eating and weight loss outcomes in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1447–1455. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Department of Health and Human Service; Public Health Service; Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Memorandum. Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). Appendix 2: Request to Sponsors - Advice for the pharmaceutical industry in exploring their placebo-controlled clinical trials databases for suicidality and preparing data sets for analysis by FDA. 2006 November 16; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/briefing/2006-4272b1-01-fda.pdf.