Abstract

Mutations in the TUBB3 gene, encoding β-tubulin isotype III, were recently shown to be associated with various neurological syndromes which all have in common the ocular motility disorder, congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscle type 3 (CFEOM3). Surprisingly and in contrast to previously described TUBA1A and TUBB2B phenotypes, no evidence of dysfunctional neuronal migration and cortical organization was reported. In our study, we report the discovery of six novel missense mutations in the TUBB3 gene, including one fetal case and one homozygous variation, in nine patients that all share cortical disorganization, axonal abnormalities associated with pontocerebellar hypoplasia, but with no ocular motility defects, CFEOM3. These new findings demonstrate that the spectrum of TUBB3-related phenotype is broader than previously described and includes malformations of cortical development (MCD) associated with neuronal migration and differentiation defects, axonal guidance and tract organization impairment. Complementary functional studies revealed that the mutated βIII-tubulin causing the MCD phenotype results in a reduction of heterodimer formation, yet produce correctly formed microtubules (MTs) in mammalian cells. Further to this, we investigated the properties of the MT network in patients' fibroblasts and revealed that MCD mutations can alter the resistance of MTs to depolymerization. Interestingly, this finding contrasts with the increased MT stability observed in the case of CFEOM3-related mutations. These results led us to hypothesize that either MT dynamics or their interactions with various MT-interacting proteins could be differently affected by TUBB3 variations, thus resulting in distinct alteration of downstream processes and therefore explaining the phenotypic diversity of the TUBB3-related spectrum.

INTRODUCTION

Malformations of cortical development (MCD) encompass various cortical disorders that include, but are not exclusive to, the agyria–pachygyria spectrum (absent or reduced number of cortical folds) and polymicrogyria (PMG) (excessive small gyri with abnormal cortical lamination), which result in moderate to severe encephalopathies. MCD are believed to result from the alteration of several stages of cortical development from proliferation and migration of neuronal cells, to organization of their final position within cortical layers. Over the last few years, evidence demonstrating the critical role of the cytoskeleton network in proper cortical development was reported. The importance of microtubules (MTs) was further emphasized due to its association to mutations in genes encoding for α-tubulin (TUBA1A, TUBA8) (MIM *602529 and *605742) and β-tubulin (TUBB2B) (MIM *612850) subunits in lissencephaly and PMG (1–5). Moreover, neuropathological studies of TUBA1A- and TUBB2B-mutated fetus showed neuronal migration defects and features of axonal guidance disorganization. This was confirmed by investigations of the Tuba1aS140G/+ mouse model and through in utero Tubb2b RNAi approaches. Tuba1aS140G/+ mutant mice displayed hippocampus lamination defects, and in vivo reduction of Tubb2b led to aberrant radial migration (1–3). Biochemical and cellular investigations revealed α-/β-tubulin heterodimer assembly defects, which strengthened the in vivo data, suggesting that haploinsufficiency and MT dysfunctions underlie these migration defects.

Recently, the importance of MTs in axonal guidance was further established by Tischfield et al. (6) through complementary genetic and functional investigations. They have indeed shown that heterozygous TUBB3 missense mutations (MIM *602661) are implicated in various neurological disorders encompassing either isolated congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscle type 3 (CFEOM3) (MIM no. 600638) or in association with early- to late-onset polyneuropathy and developmental delay. Neuroimaging data of patients with TUBB3 mutations revealed a spectrum of abnormalities that include hypoplasia of oculomotor nerves and dysgenesis of the corpus callosum and the internal capsule. In contrast to phenotypes related to TUBA1A, TUBB2B and TUBA8 mutations (5,6), no cortical dysgenesis and gyral abnormalities were observed in TUBB3-related phenotypes reported by Tischfield et al. (6).

However, in continuation with our previous findings (1–3), we tested TUBB3 in MCD patients with or without cerebellar defects because of its similar spatio-temporal expression to TUBA1A and TUBB2B, and showed that its implications in cortical dysgeneses are characterized by gyral abnormalities.

RESULTS

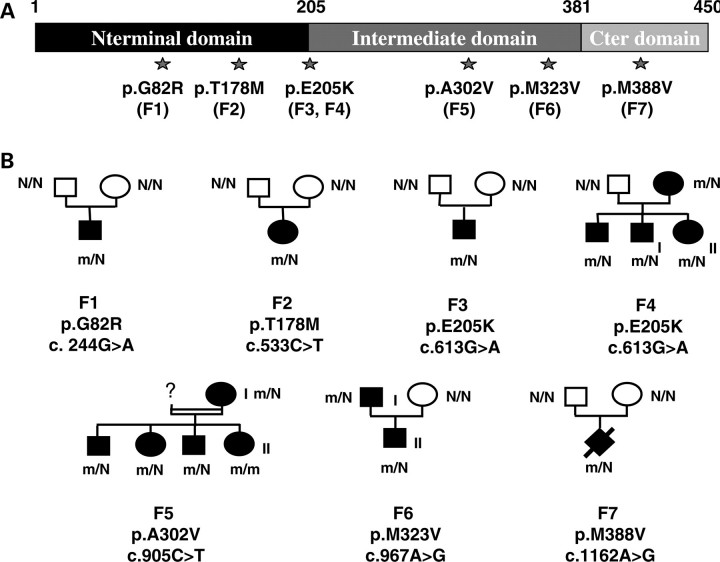

Mutations in TUBB3 are responsible for de novo and inherited neurological disorders

Following a previous study focused on a patient panel with the lissencephaly–pachygyria spectrum (2) and the implication of TUBB2B in PMG, we expanded the screening of the TUBB3 gene to a new cohort of 120 individuals with MCD, preferentially encompassing PMG, gyral disorganization and simplification syndromes with or without pontocerebellar defects. We identified six novel TUBB3 missense mutations (p.G82R, p.T178M, p.E205K (recurrent), p.A302V, p.M323V and p.M388V) in 12 patients from seven independent families (3 inherited familial forms and 4 sporadic cases, Fig. 1). One mutation resides in exon 3 and five in exon 4. All of them modify highly conserved amino acids and segregate with the phenotype in each family. In the particular case of family 5 native of the northwest region of France, we identified a p.A302V TUBB3 homozygous mutation in a young girl (F5-II) and the same heterozygous mutation in her less affected mother (F5-I). The father of the F5-II girl was not accessible for phenotypic testing and therefore his DNA was unavailable for analysis. The search for a loss of heterozygosity was performed by Illumina SNP array experiments and allowed the exclusion of the TUBB3 deletion and revealed a high level of homozygosity for the F5-II patient, who presented the first recessive form of a TUBB3 mutation (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1), suggesting that parents of this patient are consanguineous. For the other families, segregation analyses of TUBB3 mutations are coherent with de novo or familial dominant transmission of MCD. Furthermore, all variants were not detected in 360 normal controls of Caucasian origins.

Figure 1.

Mutations in the TUBB3 gene in cases of MCD. (A) Primary sequence of the βIII-tubulin protein showing the position of MCD-associated substitutions. (B) Pedigrees of families with TUBB3 mutations reported in this study. Square, male; round, female; diamond, fetus. Black colouring, affected individual; N, normal allele; m, mutated allele.

TUBB3 mutations result in cortical malformations associated with axon guidance defects

In order to better define the phenotype corresponding to TUBB3 mutations, nine mutated patients were retrospectively re-examined (Table 1). The large majority of patients with TUBB3 mutations were referred to paediatric neurology consultations for either delayed acquisition of developmental milestones or mental retardation at school age. On examination, all, except one (F5-1), presented axial hypotonia, and spastic diplegia or tetraplegia (three of nine, Table 1). All tested patients exhibit intermittent (three of seven) to permanent (four of seven) strabismus combined with either multidirectional (two of four) or horizontal (two of four) nystagmus. None presented ptosis or external ophthalmoplegia, and fundoscopy was normal in all cases.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical phenotypes and MRI features associated with TUBB3 mutations

| Patient (sex/age) mutation | OFC | Motor delay | Cognitive function | Epilepsy | Ophthalmological | Cortical dysgenesis |

Cerebellum |

Brainstem | Corpus callosum | Basal ganglia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of CD | Predominant location | Cerebellar vermis | Cerebellar Hemisphere | |||||||||

| F1 (M/3y) p.G82R | 50th p | Axial hypotonia | Moderate MR | Absent | Strabismus | Multifocal PMG / microgyria | Perisylvian and frontal | Dysplastic | N | Hypoplastic | Posterior agenesis | Fusion caudate/putamen hypertrophic |

| F2 (F/1y) p.T178M | <3rd p | Severe axial hypotonia, spastic tetraplegia | Not determined (ND) | Refractory neonatal epilepsy | Multidirectional nystagmus/intermittent strabismus | Gyral disorganization | Global gyral disorganization | Hypoplasia | Severely dysplastic | Hypoplastic | Complete agenesis | Fusion caudate/putamen/hypertrophic |

| F3 (M/8y) p.E205K | 3rd p | Mild spasticity, orofacial dyspraxia | Moderate MR | Absent | Strabismus | Multifocal PMG | Perisylvian and frontal | Dysplastic | N | Hypoplastic | Thick | Fusion caudate/putamen/hypertrophic |

| F4-I (M/10y) p.E205K | 10th p | Axial hypotonia | Severe MR | Prolonged febrile seizures | Normal | PMG | Perisylvian | Dysplastic | N | Hypoplastic | Thin | Fusion caudate/putamen |

| F4-II (F/14y) p.E205K | 10th p | Axial hypotonia | Severe MR | Absent | Normal | PMG | Perisylvian | Dysplastic | N | Hypoplastic | Thin | Fusion caudate/putamen |

| F5-II (F/1y) p.A302V | 3rd p | Axial hypotonia | Not evaluable | absent | Multidirectional nystagmus/intermittent strabismus | Gyral disorganization | Frontoparietal | Dysplastic | N | Hypoplastic | Thin | Fusion caudate/putamen |

| F5-I (F/37y) p.A302V | 10th p | Absent | Mild MR | Absent | Intermittent strabismus | Gyral disorganization | Frontoparietal | Dysplastic | N | N | N | N |

| F6-I (M/36y) p.M323V | 3rd p | Axial hypotonia, spastic diplegia | Severe MR | Absent | Strabismus/horizontal nystagmus | Gyral disorganization | Frontoparietal | Dysplastic | Dysplastic | Hypoplastic | Thin | Hypertrophic/mild fusion |

| F6-II (M/2y) p.M323V | 25th p | Axial hypotonia | Language delay | Absent | Strabismus/horizontal nystagmus | gyral disorganization | Frontoparietal | Dysplastic | N | Hypoplastic | Thin | hypertrophic/mild fusion |

p., percentile; ND, not determined; y, years; MR, mental retardation; OFC, occipitofrontal head circumference; Ht, heterozygous; Hm, homozygous; N, normal; PMG, polymicrogyria.

The severity of mental retardation ranged from mild to severe mental retardation. All, except patient F5-I, acquired with some delay the ability to walk before the age of 3 years, and were able to use words, although speech and language development were delayed in all cases. None presented behavioural disturbance. None presented facial weakness or congenital contractures of wrist and finger or signs of polyneuropathy. Epilepsy was reported in two cases, consisting of refractory and multifocal epilepsy in one case, and occasional prolonged febrile seizures in another patient.

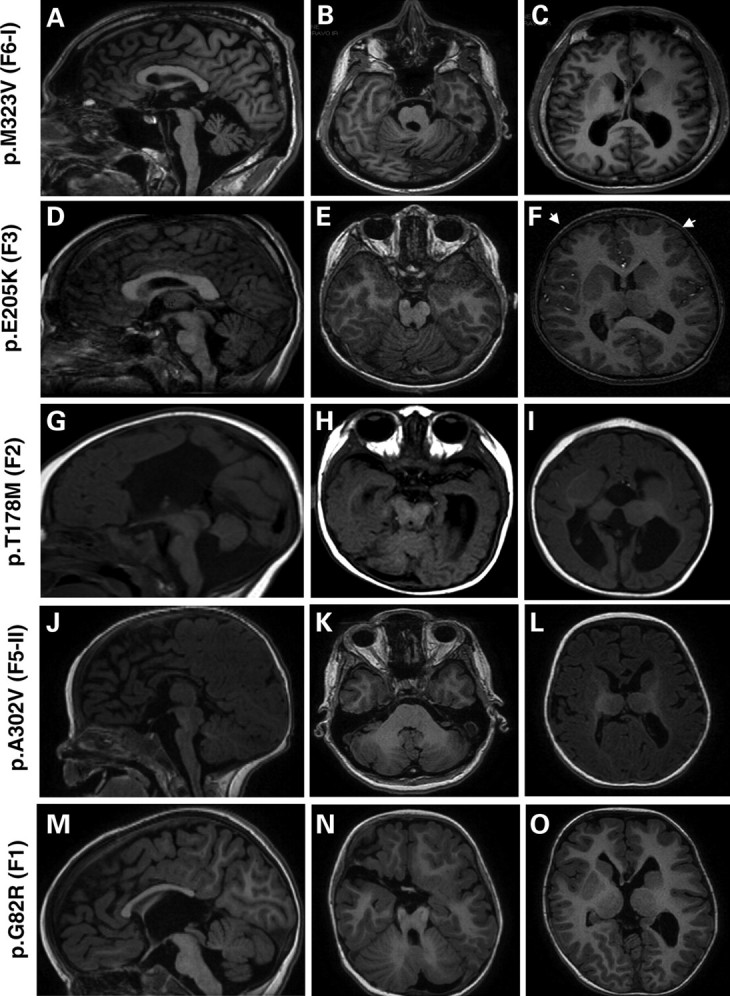

MRI of patients with mutations in TUBB3 (Fig. 2) showed a common complex cortical dysgenesis that combined frontally predominant microgyria (four of nine) (Fig. 2F) or gyral disorganization and simplification (five of nine) (Fig. 2C), dysmorphic and hypertrophic basal ganglia with fusion between putamen and caudate nucleus (eight of nine), cerebellar vermian dysplasia (nine of nine), hypoplastic brainstem (eight of nine) and hypoplastic corpus callosum (eight of nine) (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2.

MRI of patients with TUBB3 mutations (A–O). Midline sagittal MRI showing the spectrum of corpus callosum abnormalities in patients with TUBB3 mutation: it appears either thick (D), thin (A and J) with an agenesis of its posterior part (M) or with a total agenesis (G). At the brainstem level, TUBB3 mutations are associated with mild (D and M) to moderate (A, G and J) hypoplasia of the brainstem. Axial MRI at the level of cerebellar vermis shows a different degree of vermian dysplasia, severe dysplasia of the vermis and hemisphere (B and N), moderate vermian dysplasia (E) and mild vermian dysplasia (H and K) and hypoplasia of the vermis (H). Axial MRI at the level of basal ganglia shows frontally predominant microgyria (white arrows F), and gyral disorganization consisting of small gyri with parallel orientation mainly in the frontal region (C, I and O) and hypertrophic and dysmorphic basal ganglia in all cases (C, F, I and O).

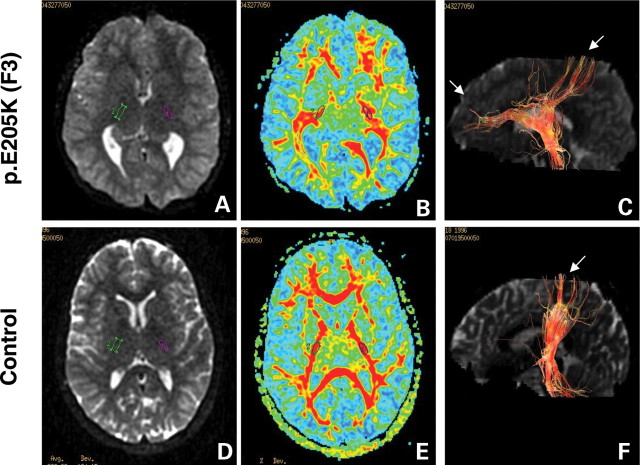

Tractography studies of the corticospinal tract at the level of the posterior arm of the internal capsule reveal progressively smaller tract size and misorientation of the pyramidal fibres (Fig. 3). This analysis also revealed the presence of aberrantly oriented fibre tracts and cortical projections. These diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies, together with the anatomic findings of dysmorphic and hypertrophic basal ganglia with fusion between putamen and caudate nucleus, further reinforce the hypothesis that a general defect in axonal guidance is associated with TUBB3 mutations.

Figure 3.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) of corticospinal tracts in TUBB3 mutation p.E205K (F3) and control individuals. Diffusion-weighted axial images (A and E) show dysmorphic basal ganglia with fusion between caudate and putamen, and virtually no visible anterior arm of the internal capsule, while the posterior arm appears hypertrophic in the patient with TUBB3 mutation (A) compared with control (D). Green and purple circles identify regions of interest (ROI 35 mm2) in the posterior arm of the internal capsule. DTI colour maps (B and E) show the dysmorphic internal capsule in patients with TUBB3 mutation (B) compared with control subjects (F). For all images, colour depicts the predominant fibre direction. The vector analysis of the colour maps is assigned to red (superoinferior), green (anteroposterior) and blue (left to right). The intensities of the colour map are scaled in proportion to the fractional anisotropy (FA). Three-dimensional reconstruction in the sagittal plane of the corticospinal tract at the level of the posterior arm of the internal capsule (C and F) shows progressively smaller tract size and misorientation of the pyramidal fibres, directed in both anteroposterior and superoinferior directions compared (C) with the control patient (F).

Notably, the most severely affected patient (F2), with severe microcephaly and virtually no development, showed the more complex cerebral malformation, combining global gyral disorganization, complete corpus callosum agenesis and cerebellum dysplasia that also affected the hemisphere with vermian hypoplasia.

On the other hand, the less severely affected F5-I patient with mild mental retardation showed frontoparietal gyral disorganization without basal ganglia and corpus callosum abnormalities (Table 1).

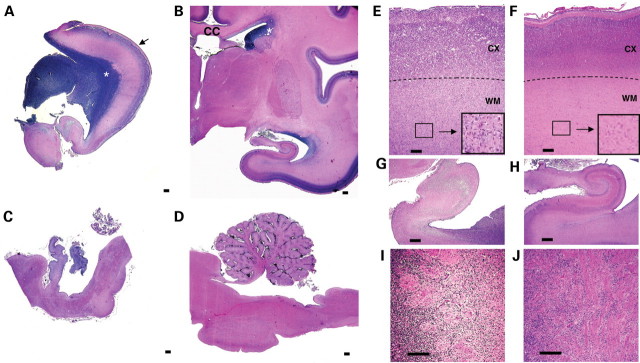

Neuropathological analyses of the fetus with p.M388V TUBB3 mutation

One of the mutations (p.M388V) was identified in a fetal case (F7) in which the pregnancy was terminated in accordance with French law at 27 weeks of gestation after a diagnosis of microcephaly and corpus callusom during an ultrasound examination. Macroscopic neuropathological analysis of the fetal brain showed micro-lissencephaly with severe brainstem and cerebellar hypoplasia (Fig. 4A–D), olfactory bulbs agenesis, optic nerve hypoplasia and dysmorphic basal ganglia. Detailed histopathological and immunostaining analysis further disclosed abnormally voluminous germinal zones, a severely disorganized cortical plate with a festooned-like pattern (Fig. 4C, D and Supplementary Material, Fig. S2), associated with a disturbed cortical cytoarchitecture and neuronal differentiation with no clear limitation between white and grey matter (Fig. 4E, F and Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). In addition, caudate nucleus, putamen and pallidum were absent, and thalami were hypoplastic and crudely shaped (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). Migration abnormalities were clearly suggested by abnormal cortical and hippocampal cytoarchitectony, aberrant cortical interneurons number and localization (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2E–H) and by heterotopic neurons in the white matter (Fig. 4E and F). Complementary histological examination confirmed a lack of callosal fibres and revealed the absence of corticospinal tracts. Aberrant fibre bundles were found in great quantities in the superficial cortical layer and in the periventricular regions, suggesting axonal guidance defects (Fig. 4I and J and Supplementary Material, Fig. S2I and J).

Figure 4.

Histopathological analysis of p.M388V fetal case. NissI-stained sections of the 27 GW fetus (A and C) showing microlissencephaly, corpus callosum agenesis, ‘wavy’ cortical layer 2 (black arrow), voluminous germinal zone (white asterisk), vermian and cerebellar hypoplasia compared with an age-matched control (B and D). The histological analysis of the p.M388V fetal case revealed (E, G and I) the presence of gyral abnormalities (festooned-like surface), unlayered cortex with no clear limitation between white and grey matter (E and F), heterotrophic neurons in the white matter (E and F, zoom in black boxes), disorganized hippocampal structures (G and H) and abnormal axonal bundles in the ventricular zone (I and J). CC, corpus callosum; CX, cortex; WM, white matter. Scale bar: 500 µm (A–D), 100 µm (E–J).

TUBB3 mutations impair the formation of α-/βIII-tubulin heterodimers

To explore the functional consequences of the mutations on TUBB3 functions, we first determined the localization of each mutation within the secondary structure of the βIII-tubulin polypeptide (7). All mutated residues (p.G82, p.T178, p.E205, p.A302 and p.M323) were localized in H–S loops (H2–B3, B5–H5, B6–H6, H9–B8 and B8–H10) and one (p.M388V) in the H11 helix (Fig. 5A–C). Interestingly, detailed analysis showed that three residues (p.G82, p.T178 and p.M323) (Fig. 5A and B) were located in the surface area of tubulin, on the opposite side of p.R262, p.E410 and p.D417 mutations reported by Tischfield et al. (6) (Fig. 5D and E). According to structural data, only one mutated residue (T178) is likely to influence GTP binding as it lies in proximity to the ribose of the nucleotide. Neither of the remaining mutations seems to affect the binding pocket of βIII-tubulin.

Figure 5.

Tubulin structure and positions of TUBB3 amino acid substitutions associated with MCD, in comparison with TUBB3 amino acid substitutions associated with CFEOM3. (A and B) Structural representation (face A) of the α-/β-heterodimer depicted with (A) or without surface delimitation (B), revealing relative positions of MCD TUBB3 amino acid substitutions either inside the monomer (p.E205K, p.A302V and p.M388V) or on the surface (p.G82R, p.T178M and p.M323V). α- and β-subunits are, respectively, represented in light and dark grey. Contrary to helices that are in grey, β-strands are visualized in dark blue. Localization of TUBB3 amino acid substitutions is summarized in (C). (D and E) Structural representation (face B) of the α-/β-heterodimer depicted with (D) or without surface delimitation (E), revealing relative positions of CFEOM3 TUBB3 amino acid substitutions either inside the heterodimer (p.R62, p.A302 and p.R380) or on the surface (p.R262, p.E410 and p.D417). These representations (A–E) show that amino acid substitutions localized on the surface are on opposite sides in case of CFEOM3 (Face B, in D and E) and MCD mutations (Face A, in A and B).

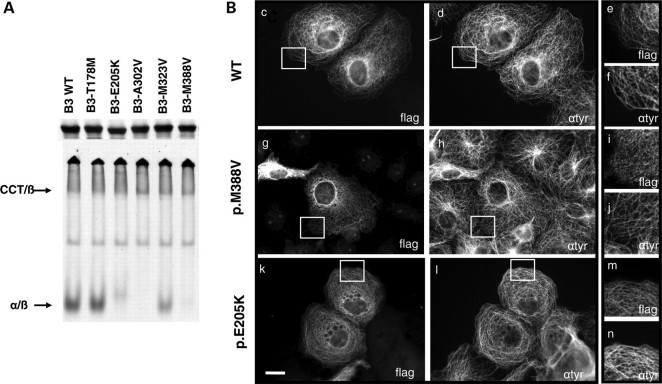

To further investigate functional consequences of the mutations, we expressed the β-tubulin mutants in rabbit reticulocyte lysate and studied its ability to assemble into α-/β-heterodimers in the presence of bovine brain tubulin (Fig. 6). First, we found that the five mutants (p.G82R was not tested) were translated as efficiently as the wild-type control (Fig. 6A). However, analysis of the same reaction products under native conditions revealed a range of heterodimer formation that in most cases differed both quantitatively and qualitatively from the wild-type control (Fig. 6A). Though mutant p.T178M generated heterodimers with efficiency comparable to the WT control, it was remarkable to note that p.E205K, p.A302V and p.M388V mutant polypeptides yielded no discernable amount of heterodimer (Fig. 6A). The remaining mutant p.M323V did generate heterodimers, but with a diminished yield. These results reveal the impairment of tubulin heterodimerization processes in four of the five tested mutants.

Figure 6.

In vitro and in vivo consequences of TUBB3 overexpression in WT and mutants concerning heterodimerization processes and MT incorporation. (A) Mutations in TUBB3 result in inefficient α-/β-tubulin heterodimer formation in vitro. Analysis by SDS–PAGE and non-denaturing gel of in vitro transcription/translation products conducted with 35S-methionine-labelled wild-type (WT) and five different TUBB3 mutants. The reaction products were further chased with bovine brain tubulin to generate α-/β-heterodimers. SDS–PAGE gel showed that the five mutants were translated as efficiently as the wild type control. Note that in non-denaturing gel condition, p.E205K, p.A302V and p.M388V mutants yielded no discernable amount of α-/β-heterodimers. The p.M323V mutant generated heterodimers comparable to WT control and the remaining mutant p.T178M in a diminished yield. (B) Expression of C-terminal FLAG-tagged TUBB3 wild-type (c–f) and mutants [p.M388V (g–i) and p.E205K (k–n)] in transfected COS7 cells revealed by anti-flag (c, g and k) and anti-tyrosinated α-tubulin (d, h and l) staining. Note the limited dotted pattern of the MT network associated with p.E205K and p.M388V mutants overexpression in some cells (i and m) compared with WT (e) and tyrosinated α-tubulin staining (f, j and n). Scale bar: 20 µm (i).

Subsequently, we analysed the localization of βIII-tubulin mutants upon overexpression in different cell types. The transfection of the flag-tagged TUBB3-mutated constructs in COS7 and HeLa cells revealed a similar incorporation of variant βIII-tubulin proteins into MTs compared with the control (Fig. 6B and data not shown). Two mutants, p.E205K and p.M388V, produced in some cells a dotted localization pattern, suggesting a subtle impairment of its ability to incorporate into the cytoskeleton (Fig. 6B). Moreover, complementary investigations of the MT network of p.T178M and p.E205K patients’ fibroblasts confirmed that no major alterations were observed in the MT network of the cells (data not shown). All biochemical and cellular results reveal that most of the mutations described in this study alter the efficiency of the tubulin heterodimerization process; this is most likely to be independent of GTP-binding mechanisms. It also suggests that the formed heterodimers are able to fully incorporate into MT networks.

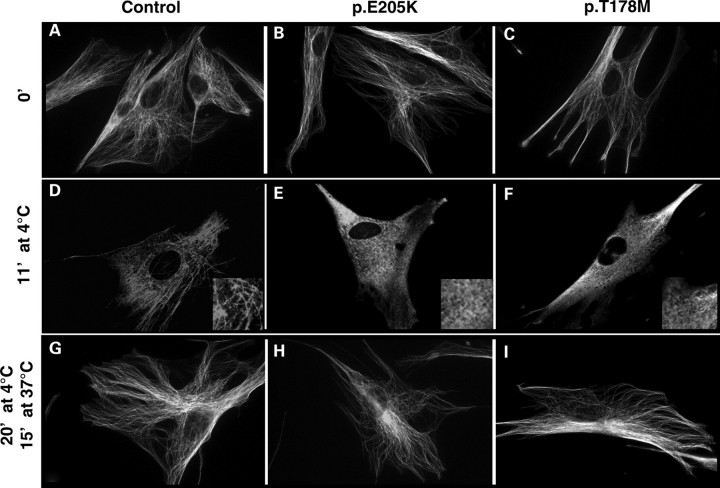

TUBB3 mutations associated with MCD impair MT stability

To further assess the effect of MCD-related TUBB3 mutations on MT dynamics, we explored MT behaviour in fibroblastic cells of two patients who, respectively, carry the p.T178M and p.E205K TUBB3 mutations. We first showed by RT–PCR, immunocytochemistry and western blotting using the monoclonal antibody tuj1 and primary cultures of neuronal cells (used as positive control), glial cells (used as a negative control) and fibroblasts that TUBB3 is significantly expressed in fibroblasts (data not shown). In order to assess the potential consequences of these mutations on MT dynamics, we analysed the response of the cytoskeleton of fibroblasts established from control and affected patients to cold-induced depolymerization treatment followed by a repolymerization step at 37°C. First, we examined by immunofluorescence staining of α-tubulin the cytoskeleton morphology and the pool of unincorporated tubulin in mutant cells at various times of cold treatment. Results corresponding to these experiments (Fig. 7) consistently showed that p.T178M and p.E205K mutations lead to decreased cytoskeleton resistance to cold treatment compared with that in control samples. We have found that complete MT depolymerization occurred after only 11 min of cold treatment for the p.T178M and p.E205K mutants in comparison with control cells which are depolymerized after 15 min at 4°C (Fig. 7). These data suggest that mutated MTs are less stable than normal ones.

Figure 7.

In vivo analysis of cytoskeleton behaviour and stability using patients’ fibroblasts carrying TUBB3 p.T178M and p.E205K mutations. Evaluation of the sensitivity of MTs to cold treatment was analysed in control fibroblasts (A, D and G) and patient fibroblasts with p.E205K (B, E and H), p.T178M (C, F and I) TUBB3 mutations before (A–C) and after 11 min of cold treatment at 4°C (D–E) to show the resistance of MT to depolymerization. Note the increased sensitivity of patient's fibroblasts to cold treatment. The capacity of the cytoskeleton to repolymerize was assessed after 20 min at 4°C and 15 min at 37°C (G–I).

DISCUSSION

One gene, several phenotypes

In this study, we provide evidence showing that missense mutations in the TUBB3 gene are causative of MCD associated with neuronal migration defects, white matter abnormalities and pontocerebellar hypoplasia. In addition to corpus callosum abnormalities, MRI and tensor diffusion analysis demonstrated that phenotypes resulting from TUBB3 mutations encompass cortical defects, such as gyral simplification or PMG associated with cerebellar dysgenesis, corticospinal tracts dysgenesis and fibre projection defects. In accordance with the gyral disorganization/simplification and cerebellar dysgenesis presented by all patients, detailed histological investigations showed the presence of unlayered cerebral and cerebellar cortices and heterotopic neurons in the white matter, demonstrating neuronal migration impairment.

Consequently, our findings expand the spectrum of TUBB3 phenotypes previously described to MCD associated with neuronal migration, organization and/or differentiation defects. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that fine oculomotor nerve defects could be the cause of strabismus in MCD patients described in this study, and the absence of additional ophthalmological impairment indicates that ocular motility disorder, CFEOM3, is not a constant feature of TUBB3 syndrome as previously described by Tischfield et al. (6). Though phenotypes described in this study are different from those reported by Tischfield et al. (6), it is worth mentioning this could be the consequence of a bias in patients recruitment due to the distinct ophthalmological and neurodevelopmental research field developed, respectively, by the two laboratories.

Segregation of phenotypes associated with mutations in TUBB3

In contrast with TUBA1A and TUBB2B mutations, we show that mutations in the TUBB3 gene are either inherited (three mutations) or de novo (four mutations). In all but one of the familial cases, the variations are found in a heterozygous state as they correctly segregate with the phenotype in an autosomal dominant manner and are effected with complete penetrance. The occurrence of familial dominant forms of mild developmental impairment and MCD associated with mutations in the TUBB3 gene contrasts with the systematic de novo occurrence of mutations in TUBA1A and TUBB2B in association with severe phenotypes.

However, in the case of family 5 which carries the p.A302V mutation, it is worth mentioning that the mother, who is heterozygous for the mutation, is mildly affected, whereas her homozygous daughter is severely affected. These results suggest that TUBB3 mutations could also exist in a homozygous state and that the severity of the related phenotype is likely to depend on the number of mutated alleles. Nevertheless, the severity of the phenotype presented by a given patient could not only be predicted based on its heterozygous or homozygous status since the de novo heterozygous p.T178M and p.M388V mutations are associated with phenotypes which are more severe than the one associated with the homozygote p.A302V mutation.

CFEOM3 and MCD mutations alter distinct amino acids

To date, all known variations of the TUBB3 gene are missense mutations. Neither nonsense mutations nor intragenic deletions have been identified independently from the associated phenotype. In this work, we described six novel TUBB3 alterations associated with MCD phenotypes, while previously reported mutations (6) are associated with CFEOM3 syndrome, with no cortical abnormalities. Interestingly, the mutations identified in the two studies affect distinct amino acids. However, in the specific case of the A302 amino acid residue, the nature of the variation seems to have a clear influence on the resulting phenotype. Indeed, p.A302T and p.A302V mutations result in CFEOM3 and MCD syndromes, respectively. Although TUBB3 mutations could lead to a wide range of clinical and imaging phenotypes, it is worth mentioning that recurrent mutations are associated with similar clinical and magnetic imaging features, suggesting that each variation could have a specific consequence on βIII-tubulin function.

Using the model of human β-tubulin developed by Nogales et al. (7), we determined the localization of each mutation implicated in MCD or CFEOM3 syndromes within the secondary structure of the βIII-tubulin polypeptide. Detailed analysis shows that three mutated residues in MCD disorders (p.G82, p.T178 and p.M323) were located at the surface of the tubulin, on the opposite side of p.R262, p.E410 and p.D417 mutations reported by Tischfield et al. (6), suggesting that these two groups of mutations could impair MTs and/or their interactions with MAPs critical for MT functions in different ways. Our results give evidence that mutations associated with different phenotypes (CFEMO3 versus MCD) might reside in different functional areas of the protein. Thus, in the context of tubulin genes, genotype/phenotype correlations must be assigned not only by considering the primary sequence of the protein, as is classically done, but also by considering the tertiary sequence and the three-dimensional arrangement of the protein. This approach might be more informative as protein interactions largely contribute to MT functions during neuronal migration and differentiation in the context of tubulins and tubulin polymers.

Molecular pathophysiology underlying CFEOM3 and MCD syndromes

One of the intriguing issues raised by TUBB3 mutations and their associated phenotypes is the allelic phenotypic heterogeneity, i.e. how missense mutations located in the TUBB3 gene lead either to CFEOM3 or MCD phenotypes. As none of the mutations is common to both studies, it appears at first sight that both the position and the nature of the resulting amino acid from TUBB3 mutations influence the clinical phenotype. Nevertheless, biochemical experiments show that most of the TUBB3 variations have the same negative effect on tubulin heterodimerization, independent of the associated phenotype. Indeed, we showed that four of our five tested mutants associated with cortical malformations have an impaired capacity to form αβ heterodimers, probably through GTP-binding-independent mechanisms as none of the mutations localizes in the GTP-binding pocket. These biochemical consequences were similar to those described by Tischfield et al. who reported the study of eight TUBB3 mutations implicated in oculomotor disorders. Moreover, cellular analysis demonstrates that in all cases, formed heterodimers are able to fully incorporate into MT networks, suggesting that neither the heterodimerization process nor the incorporation into MTs is a sufficient criterion to explain the phenotype variability observed in TUBB3 mutations. However, mutation-related specific phenotypes could potentially result from different consequences on MT dynamics and function, as well as their interacting proteins. This hypothesis is reinforced by the result of cold-treatment experiments suggesting a stability defect of the MT network in fibroblasts bearing p.T178M and p.E205K mutations, as well as by the tri-dimensional modelling discussed above. Interestingly, these findings contrast with those reported by Tischfield et al. (6) who pointed out that p.R262C substitution, a mutation shown to be associated with the CFEOM3 phenotype, leads to an increased MT stability demonstrated by two different approaches.

Though data reported in this study will contribute to the improvement of the diagnosis of MCDs, deciphering the consequences of TUBB3 mutation on MT and MAP dynamics and functions, as well as understanding of the phenotypic heterogeneity associated with these mutations, will require further investigations. Together, our findings with the recent data demonstrating the implication of TUBA8, TUBB2B and TUBA1A in cortical dysgenesis disorders should provide further insights to explore the role of MTs in brain development and into how tubulin isotypes dysfunction lead to cortical malformation disorders. Also, in view of the increasing number of tubulin genes shown to be involved in MCD and neurological syndromes, further studies to reveal the full spectrum of disorders associated with mutations in other family members of the tubulin genes will also be of interest.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic analysis of TUBB3 clinical assessment

As part of our lissencephaly research programme, we collected samples with diffuse cortical malformations, including the gyral simplification spectrum (n = 40), and PMG (n = 80) negative for DCX, LIS1, ARX, TUBA1A, GPR56 and TUBB2B mutational screening. We obtained informed consent from parents of affected individuals using protocols approved by local institutional review boards at L'Hôpital Cochin and INSERM (Medical Research Institute). For each patient, the complete TUBB3 coding sequence and splice sites were amplified, respectively, in five independent PCR reactions from genomic DNA and were sequenced using the BigDye dideoxy-terminator chemistry and ABI3700 DNA Analyser (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA). Primer sequences and PCR conditions are available upon request.

Clinical assessment and imaging analysis

Clinical data were provided by the physicians who are responsible for the medical welfare of the patients. All patients with mutations in TUBB3 were retrospectively re-examined after the identification of a TUBB3 mutation. Also, all brain-imaging data were reviewed in order to identify characteristic changes of cortical malformations associated with TUBB3 mutations. Tractography imaging was realized as previously described in Wahl et al. (8).

Neuropathological and immunohistochemical studies

The fetal neuropathological studies were performed after termination of pregnancy at 27 gestational weeks (GW) due to detected malformations, in accordance with French legislation. After removal from the skull, the fetal brain was fixed in a 10% formaldehyde solution containing NaCl (9 g/l) and ZnSO4 (3 g/l) for 3–6 weeks according to the volume of the brain. The brain was cut in a coronal plane and sections were embedded in paraffin. Paraffin blocks were cut at either 5 µm (brainstem and cerebellum) or 7–10 µm (hemispheres). Sections were stained with haemalun–phloxin or cresyl violet according to standard methods.

Immunohistochemical procedures were performed at the same time for the mutated patient and one control case of the same age. Paraffin sections were immunostained for glial fibrillary acidic protein with a polyclonal antibody (1:200–1:400, Dako, USA), vimentin, NeuN (1:500, MAB377, Chemicon), Reelin (1:1000, clone 142) (9), MAP2 (1:100, HM2, Sigma), Calbindin (1:500, Swant Laboratories, Switzerland), Calretinin (1:1000, Swant Laboratories), MIB1 (1:75, Dako) and Tuj1. The Universal Immunostaining System Streptavidin-Peroxydase Kit (Coulter) was used to reveal the reaction. Slides were labelled as previously described in Fallet-bianco et al. (10). After realization, haematoxylin was used to counterstain the brain sections.

All sections were examined under a light microscope (Eclipse 800 Nikon) and some were selected for photographic documentation.

Protein modelling

A model of human β-tubulin was built by homology modelling using available structures (Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics PDB code 1TUB) from Nogales et al. (7). The images in Figure 4 were rendered using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org).

Cloning and in vitro translation

The full-length cDNA encoding the human TUBB3 sequence was generated by PCR using a template from the human brain cDNA library (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The PCR product was cloned into the pcDNA 3.1-V5-His vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and checked by DNA sequencing. These products were cloned both into the cDNA3.1-V5-his-TOPO-TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) and pET vector. An in-frame tag encoding the FLAG epitope (DYKDDDDK) was incorporated by PCR along with the C-terminus of the TUBB3 wild-type sequence to allow the distinction of the transgene from other highly homologous endogenously expressed α-tubulin polypeptides. Various mutations corresponding to those associated with cortical dysgenesis were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange II kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Transcription/translation reactions were performed at 30°C for 90 min in 25 µl of rabbit reticulocyte lysate (TNT; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) containing 35S-methionine (specific activity, 1000 Ci/µmol; 10 µCi/µl). For the generation of labelled α-tubulin heterodimers, transcription/translation reactions were chased for a further 2 h at 30°C by the addition of 0.375 mg/ml of native bovine brain tubulin. Aliquots (2 µl) were withdrawn from the reaction, diluted into 10 µl of gel-loading buffer (gel running buffer supplemented with 10% glycerol and 0.1% bromophenol blue) and stored on ice prior to resolution on a non-denaturing gel (11,12). Labelled reaction products were detected by autoradiography after resolution on either SDS–PAGE or on native polyacrylamide gels as described (11,12).

Cell culture, transfections and immunofluorescence

Primary cultures of fibroblasts were derived from skin biopsies taken from patients with p.T178M and p.E205K mutations and also control patients. HELA and COS7 cells were transfected by variably mutated TUBB3 constructs using the Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and grown on glass cover slips in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics. The cells were fixed with ice-cold methanol, 24–48h after growth. In the depolymerization experiments used to determine the stability behaviour of MTs after 24 h of culture, fibroblasts were incubated for various brief intervals from 0 to 30 min on ice and fixed thereafter. Repolymerization experiments were performed by successively exposing cells at 4°C during 20 and 15 min at 37°C. Cells were then labelled with a polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody (1/500), a monoclonal Tuj1 antibody (1/1000) or a monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (1/1000) (DM1A, Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St Louis, MO, USA).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.C. supervised the design and follow-up of the study and the preparation of the manuscript. K.P. and Y.S. performed genetic and molecular investigations including analysis of mutation consequences on heterodimerization and polymerization, with the help of X.H.J. for biochemical experiments. K.P., Y.S., X.H.J. and J.C. discussed the results. N.L. helped in TUBB3 screening. N.B.-B. and K.P. recruited cases and controls. N.B.-B., A.R., I.D., C.B., T.A.-B., D.G. and R.N. helped in acquiring patients and parents. N.B.-B. and N.B. re-examined the patients’ MRIs and diffusion tensor images. F.E.-R. realized neuropathological analysis and C.F.-B. immunostaining experiments. F.E.-R. and C.F.-B. interpreted neurological analysis of the fetal case. L.C.-P. performed all DNA extractions from subject samples and coordinated interaction with clinicians. B.K. performed Illumina experiments. X.H.J. computed and analysed the structure. K.P. drafted the manuscript with the help of Y.S., N.B.-B., X.H.J. and J.C.

WEB RESOURCES

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/

University of California-Santa Cruz (UCSC) genome browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/

NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Pymol Molecular Viewer, http://pymol.org

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by funding from AP-HP, INSERM, FRM (funding within the frame of the Programme EQUIPE FRM 2007) and ANR (ANR Neuro 2005, ANR MNP 2008). K.P. is a post-doctoral researcher supported by FRM (Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Nick Cowan for his helpful comments about tubulin folding and heterodimerization investigations, Dr Cherif Beldjord for his regular advice and Franck Fourniol and Dr Anne Houdusse for their helpful comments on tubulin modelling and interpretation. We are grateful to the patients and their parents who contributed in this study, as well as all the colleagues who provided clinical and imaging information. We also thank all members of Cochin Institute genomic platform, Cochin Hospital Cell Bank and Cassini diagnostic members for their technical assistance.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Keays D.A., Tian G., Poirier K., Huang G.J., Siebold C., Cleak J., Oliver P.L., Fray M., Harvey R.J., Molnár Z., et al. Mutations in alpha-tubulin cause abnormal neuronal migration in mice and lissencephaly in humans. Cell. 2007;128:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.017. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poirier K., Keays D.A., Francis F., Saillour Y., Bahi-Buisson N., Manouvrier S., Fallet-Bianco C., Pasquier L., Toutain A., Tuy F.P., et al. Large spectrum of lissencephaly and pachygyria phenotypes resulting from de novo missense mutations in tubulin alpha 1A (TUBA1A) Hum. Mut. 2007;28:1055–1064. doi: 10.1002/humu.20572. doi:10.1002/humu.20572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaglin X.H., Poirier K., Saillour Y., Buhler E., Tian G., Bahi-Buisson N., Fallet-Bianco C., Phan-Dinh-Tuy F., Kong X.P., Bomont P., et al. Mutations in the beta-tubulin gene TUBB2B result in asymmetrical polymicrogyria. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:746–751. doi: 10.1038/ng.380. doi:10.1038/ng.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdollahi M.R., Morrison E., Sirey T., Molnar Z., Hayward B.E., Carr I.M., Springell K., Woods C.G., Ahmed M., Hattingh L., et al. Mutation of the variant alpha-tubulin TUBA8 results in polymicrogyria with optic nerve hypoplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.007. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaglin X.H., Chelly J. Tubulin-related cortical dysgeneses: microtubule dysfunction underlying neuronal migration defects. Trends Genet. 2009;25:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.10.003. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tischfield M.A., Baris H.N., Wu C., Rudolph G., Van Maldergem L., He W., Chan W.M., Andrews C., Demer J.L., Robertson R.L., et al. Human TUBB3 mutations perturb microtubule dynamics, kinesin interactions, and axon guidance. Cell. 2010;140:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.011. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nogales E., Wolf S.G., Downing K.H. Tubulin and FtsZ form a distinct family of GTPases. Nature. 1998;391:199–202. doi: 10.1038/nsb0698-451. doi:10.1038/34465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahl M., Barkovich A.J., Mukherjee P. Diffusion imaging and tractography of congenital brain malformations. Pediatr. Radiol. 2010;40:59–67. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1448-6. doi:10.1007/s00247-009-1448-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bergeyck V., Naerhuyzen B., Goffinet A.M., Lambert de Rouvroit C. A panel of monoclonal antibodies against reelin, the extracellular matrix protein defective in reeler mutant mice. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1998;82:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fallet-Bianco C., Loeuillet L., Poirier K., Loget P., Chapon F., Pasquier L., Saillour Y., Beldjord C., Chelly J., Francis F. Neuropathological phenotype of a distinct form of lissencephaly associated with mutations in TUBA1A. Brain. 2008;131:2304–2320. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian G., Huang Y., Rommelaere H., Vandekerckhove J., Ampe C., Cowan N.J. Pathway leading to correctly folded beta-tubulin. Cell. 1996;86:287–296. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80100-2. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian G., Lewis S.A., Feierbach B., Stearns T., Rommelaere H., Ampe C., Cowan N.J. Tubulin subunits exist in an activated conformational state generated and maintained by protein cofactors. J. Cell Biol. 1997;138:821–832. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.4.821. doi:10.1083/jcb.138.4.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.