Abstract

Acute exacerbations of interstitial lung disease present as clinical deteriorations, with progressive hypoxemia and parenchymal consolidation not related to infection, heart failure or thromboembolic disease. Following single lung transplantation, patients receive maintenance immunosuppression, which could mitigate the development of acute exacerbations in the native lung. A 66-year-old man with fibrotic, nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis presented with fever, hypoxemia and parenchymal consolidation limited to the native lung four years after single lung transplantation. Investigations were negative for infection, heart failure and thromboembolic disease. The patient worsened over the course of one week despite broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy, but subsequently improved promptly with augmentation of prednisone dosed to 50 mg daily and addition of N-acetylcysteine. Hence, the patient fulfilled the criteria for a diagnosis of an acute exacerbation of pulmonary fibrosis in his native lung. Clinicians should consider acute exacerbation of parenchymal lung disease of the native lung in the differential diagnosis of progressive respiratory deterioration following single lung transplantation for pulmonary fibrosis.

Keywords: Acute exacerbation, Lung transplantation, Nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis, Pulmonary fibrosis

Abstract

Les exacerbations aiguës des maladies pulmonaires interstitielles se présentent sous forme de détériorations cliniques, accompagnées d’une hypoxémie évolutive et d’une condensation parenchymateuse non liée à une infection, à une insuffisance cardiaque ou à une maladie thromboembolique. Après la greffe d’un seul poumon, les patients reçoivent une immunosuppression d’entretien, qui pourrait atténuer l’apparition d’exacerbations aiguës du poumon natif. Un homme de 66 ans ayant une pneumonite interstitielle fibreuse non spécifique a consulté à cause de fièvre, d’hypoxémie et de condensation parenchymateuse limitée au poumon natif quatre ans après la greffe d’un seul poumon. Les examens n’ont pas révélé d’infection, d’insuffisance cardiaque et de maladie thromboembolique. L’état du patient s’est aggravé en l’espace d’une semaine malgré une antibiothérapie à large spectre, mais s’est ensuite amélioré rapidement après l’augmentation de la dose de prednisoneà 50 mg par jour et l’ajout de N-acétylcystéine. Ainsi, le patient a respecté les critères diagnostiques d’exacerbation aiguë de la fibrose pulmonaire dans le poumon natif. Les cliniciens devraient envisager une exacerbation aiguë de la maladie pulmonaire parenchymateuse du poumon natif dans le diagnostic différentiel de la détérioration respiratoire évolutive après la greffe d’un poumon en traitement d’une fibrose pulmonaire.

Acute exacerbations of interstitial lung disease present with progressive hypoxemia and parenchymal opacification not related to infection, heart failure or thromboembolic disease. Following single lung transplantation, patients receive maintenance immunosuppression, which could prevent the development of acute exacerbations in the native lung.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 66-year-old man presented in April 2010 with three days of fever, cough, shortness of breath and malaise. He had undergone a right single lung transplant in 2006 for fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (fNSIP). He was on maintenance immunosuppression with tacrolimus 0.5 mg twice daily, mycophenolate 1.5 g twice daily and prednisone 5 mg daily. The post-transplant course was complicated by acute rejection in 2006, which was treated with pulse steroids. Two years before admission, he developed grade 3 bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (1). The patient had gastroesophageal reflux, which was treated with proton pump inhibitors and laparoscopic fundoplication one year before presentation.

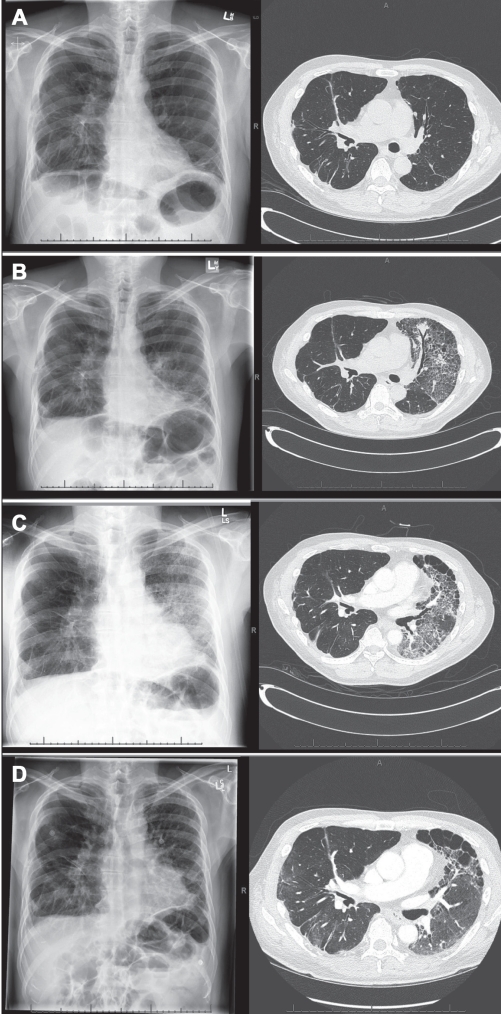

The patient had no recent sick contacts, no new medications, no travel within the previous year and no identifiable environmental exposures of concern. A chest radiograph showed patchy airspace opacification in the lower lung zone of the left (native) lung with stable (unchanged) findings in the right transplanted lung (Figure 1B). His temperature was 38.4°C, with a respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min and an oxygen saturation of 90% on room air. On chest examination, there were diminished breath sounds over the right transplanted lung and late-inspiratory crackles over the left lung base without bronchial breath sounds. The patient was admitted to hospital with presumed pneumonia and was started on intravenous meropenem, vancomycin and ganciclovir pending culture results.

Figure 1).

Chest radiographs and high-resolution computed tomography studies showing worsening diffuse ground-glass changes in the native left lung superimposed on stable findings of fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. The right lung allograft was unaffected. A Baseline three months prehospitalization. B Hospital admission. C Day 10, before prednisone pulse + N-acetylcysteine. The left lung opacification improved following institution of pulse prednisone and N-acetylcysteine (1D, day 60, following 45 days augmented prednisone + N-acetylcysteine

Arterial blood gas results revealed a PaO2 of 90mmHg on 3L/min by nasal prongs, his white blood cell count was 7.6 109/L, and his trough tacrolimus level was therapeutic. A high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan of his chest showed diffuse ground-glass opacification throughout the left native lung along with stable findings of NSIP (Figure 1B), and findings in the right lung allograft were unchanged when compared with a surveillance HRCT performed three months earlier (Figure 1A). Sputum cultures were negative for bacterial, fungal and mycobacterial pathogens. Bronchoscopy was performed, but transbronchial biopsies were not taken due to the patient’s compromised status. Minimal clear secretions were observed bilaterally. Bronchoalveolar lavage and bronchoscopic brush cultures were negative for bacterial, fungal, viral, and mycobacterial pathogens as well as for pneumocystis. There was no evidence of heart failure on transthoracic echocardiogram and no acute or chronic pulmonary embolism on contrast-enhanced computed tomography.

The fever and hypoxemia did not improve during the following week, and chest imaging showed progressive opacification of the left native lung (Figure 1C). In view of the negative cultures and parenchymal consolidation restricted to the native lung, a tentative diagnosis of acute exacerbation of fNSIP was made. Prednisone 1 mg/kg orally daily and N-acetylcysteine 600 mg orally three times/day were initiated. Over the next two weeks, the patient’s condition gradually improved and the chest radiograph returned to baseline (Figure 1D). He was discharged on prednisone, which was tapered gradually over the following four months to 20 mg daily. On discharge, he required oxygen at 4 L/min to 6 L/min by nasal prongs and, at three months postdischarge, his oxygen saturation was 93% on room air, but he continued to require supplemental oxygen with exercise.

DISCUSSION

This patient presented with fever, hypoxemia and parenchymal opacification exclusively affecting the native lung, with this unilaterality making infection and aspiration unlikely. He did not respond to broad-spectrum antibiotics, respiratory cultures were negative for pathogens, and he only improved once high dose prednisone and N-acetylcysteine (2) were initiated. Despite the absence of pathological confirmation, he fulfilled the criteria for an acute exacerbation of NSIP as described by Akira et al (3) including: subjective worsening of dyspnea within the previous month; new ground-glass opacities or consolidation on chest radiograph or HRCT; hypoxemia with decline ≥10 mmHg in PaO2 from the previous level; no evidence for infection with negative respiratory cultures and serological test results for respiratory pathogens; and no clinical evidence of pulmonary embolism, congestive heart failure, or pneumothorax as a cause of acute worsening.

Acute exacerbations have been reported in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (4), hypersensitivity pneumonitis (5), and NSIP with or without collagen vascular disease (6). The outcome of acute exacerbations in NSIP appears to be better than that in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (6).

The present case highlights that acute exacerbations can occur in the native lung even in the presence of the modest levels of immuno-suppression routinely provided for maintenance of lung allograft integrity. Clinicians should consider the possibility of an acute exacerbation of underlying pulmonary fibrosis in the differential diagnosis of progressive parenchymal opacification isolated to the native lung following single lung transplantation.

Acknowledgments

None of the authors had potential conflicts related to the topic of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Estenne M, Maurer JR, Boehler A, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome 2001: An update of the diagnostic criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:297–310. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demedts M, Behr J, Buhl R, et al. High-dose acetylcysteine in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2229–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akira M, Hamada H, Sakatani M, et al. CT findings during phase of accelerated deterioration in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:79–83. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.1.8976924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collard HR, Moore BB, Flaherty KR, et al. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:636–43. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-463PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson AL, Huie TJ, Groshong SD, et al. Acute exacerbations of fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest. 2008;134:844–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park IN, Kim DS, Shim TS, et al. Acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132:214–20. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]