Abstract

Background:

There is an alarming trend of injuries leading to poor outcome of victims in India.

Objective:

To study the profile of patients who died due to trauma and to identify factors involved in both pre-hospital and hospital care.

Materials and Methods:

A hospital-based study was performed at a trauma center in Puducherry from June 2009 to May 2010. Patients who had at least one sign of life on admission and later died were included. The demographic characteristics, injury mechanism, nature and site of injury, influence of alcohol, pre-hospital time and care, distance traveled, number of referrals, time spent in study hospital, cause of death, and missed injuries revealed at post mortem were noted.

Results:

Of the 204 fatal cases, most were between 25-65 years of age (77%); sustained injuries over weekends (36%) and between 4 pm and midnight (41%); had at least one halt in a medical facility before reaching definitive care (56%); and died within a week (63%). Adults (25-65 y) sustained most injuries (77%) on two wheelers. In those aged over 65 years, 79 percent were pedestrians. Road traffic injuries were responsible for 82 % of deaths; 16 percent were reportedly under the influence of alcohol at the time of injury. Mean delay from the time of accident to admission was 14.9 hours and median distance traveled was 30 kilometers. Head injury was the most common (66%) cause of death. Post mortem revealed skull fractures (37%), while missed injuries were noted in 8 percent, mostly involving the cervical spine and chest wall.

Conclusion:

The problem of trauma care needs to be addressed urgently in this part of southern India to reduce mortality and morbidity.

Keywords: Fatal injuries, pre-hospital care, trauma deaths

INTRODUCTION

In 2000, approximately 5 million people died from injuries globally, and 90 percent came from low or middle income countries.[1] India is also experiencing an increasing trend in injuries, particularly due to road traffic injuries (RTI) at an alarming annual rate of 3 percent.[2] The World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention indicates that by 2020, RTI will be a major killer accounting for half a million deaths and 15 million Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) lost.[3]

Evidence supports the fact that timely referral to trauma centers, equipped with proper facilities to deal with serious injuries, result in reduction of mortality among victims.[4] However, the trauma care system in India is at a nascent stage and is confined to cities and semi-urban areas.[2] Victims in India with serious injuries (ISS>9) are at six times increased risk of death compared to their counterparts from developed countries.[5]

We need to establish a comprehensive trauma care service that will ensure prompt referral of victims to definitive care centers to prevent death and disability. There is an urgent need for concerted efforts for effective and sustainable prevention and management of injuries in India. One of the essential components is development of trauma registries to monitor the system and provide state-wide cost and epidemiological statistics.[6]

Puducherry is a union territory (a sub-national administrative division of India, in the federal framework of governance) in southern India having a population of 946,600. Located on the East Coast, in the south, is a well-known tourist destination. The strategic geographical location also makes it an important junction for various commercial vehicular traffic to and from the surrounding districts of the neighboring state of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Kerala. It holds the highest accident rate in India with a fatal accident rate of 881 per million populations against the national average of 305 according to the National Crime Records Bureau report (NCRB) 2009.[7]

The information systems regarding trauma, in most places, are manual records and hence grossly inadequate. Clinical outcome of the trauma patients are available only in 40 percent of cases.[2] This severe paucity of information is the main stumbling block during planning of a policy on trauma care.

We therefore decided to study the profile of victims with fatal injuries at the Government General Hospital (headquarters hospital for the union territory) - a trauma center in Puducherry, in an attempt to identify various factors involved both in pre-hospital and hospital care in victims with a fatal outcome. This would enable us to improve the care to injured patients at various levels of the health system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used a cross-sectional study design to profile fatal trauma cases reporting to the trauma care center at Government General Hospital, Puducherry between June 2009 and May 2010. This center receives injury victims from Puducherry and the neighboring districts of adjoining states in southern India.

The government headquarters hospital at Puducherry was started by the French government nearly 150 years ago and has grown into a tertiary care level catering to a large volume of trauma cases, up to a radius of 150 km, to the tune of 1,500 seriously injured cases admitted per year. Seriously injured patients (Injury Severity Score >9) on reaching this facility are directly transported to the designated trauma room under care of general surgery. All blood investigations, imaging modalities (including CT and MRI) blood and component, services of general surgery, neurosurgery, plastic surgery, orthopedics, pediatric surgery, urological surgery, operation room, anesthesia and intensive care services are available 24 hours a day. It is a tertiary trauma care center as per Recommendations for Pre-hospital trauma care in India.[6]

All the victims who had at least one sign of life, at the time of admission to the trauma ward in the General Surgery (GS) Department, and later died during the hospital stay due to injuries were included in the study. All other cases not admitted to GS department like hanging and drowning (admitted in medicine), burns (admitted in plastic surgery), and those brought dead or only for post mortem were excluded as data collection was not possible from these subset of subjects.

For the purpose of the study we defined trauma as an injury (as a wound) to living tissue caused by an extrinsic agent,[8] examples include the consequences of motor vehicle accidents, falls, drowning, gunshots, fires and burns, and stabbing or other physical assaults. Data was recorded from the hospital records at the time of admission, directly from the patients whenever possible, their relatives, accompanying police, ambulance crew, and also from the postmortem records. Post mortem was conducted on every trauma victim who had a fatal outcome.

Clinical assessment and management was performed by various general surgery consultants including the first and second authors. The main data collection was undertaken by the first author who was the principal investigator and was assisted by postgraduate surgery trainees and nursing staff working in her team.

Interviewer-administered questionnaires were used by the investigators to gather information on various demographic characteristics of the victim, place, month and time of injury, mechanism, influence of alcohol, distance travelled to our center, number of referrals before admission to the study center and type of pre-hospital care received. Nature and site of injury, anatomical and physiological cause of death, missed injuries as per post mortem records were correlated with clinical notes. Influence of alcohol was ascertained by clinical clues/blood levels/ postmortem viscera analysis.

We classified causes of death into physiological and anatomical to avoid ambiguity in description. For example, a person with abdominal injury and ruptured spleen dies of hypovolemic shock but a person with abdominal injury and perforated viscus dies of sepsis. This should emphasize the relevance of physiological and anatomical cause of death. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) was utilized to code the cause of death.

Ethical considerations

Study permission was granted by the Medical Superintendent of the Indira Gandhi Government General Hospital, Puducherry and the Director of Health and Family welfare, Government of Puducherry. We had adhered to ethical principles while gathering the information. Confidentiality of the subjects was maintained in the department of general surgery.

Statistical methods

No formal sample size was calculated. It was decided to include all the cases that met the inclusion criteria during the study period, which covered all the seasons to discern any seasonal trend. Data was analyzed using means and proportions. F test was used as test of significance at P value < 0.05. Missing data were reported.

RESULTS

We had a total of 6,794 trauma cases (both fatal and non-fatal) that reported to our center during the study period. Of the 407 fatal cases, 204 cases (177 males, 87%) met the inclusion criteria.

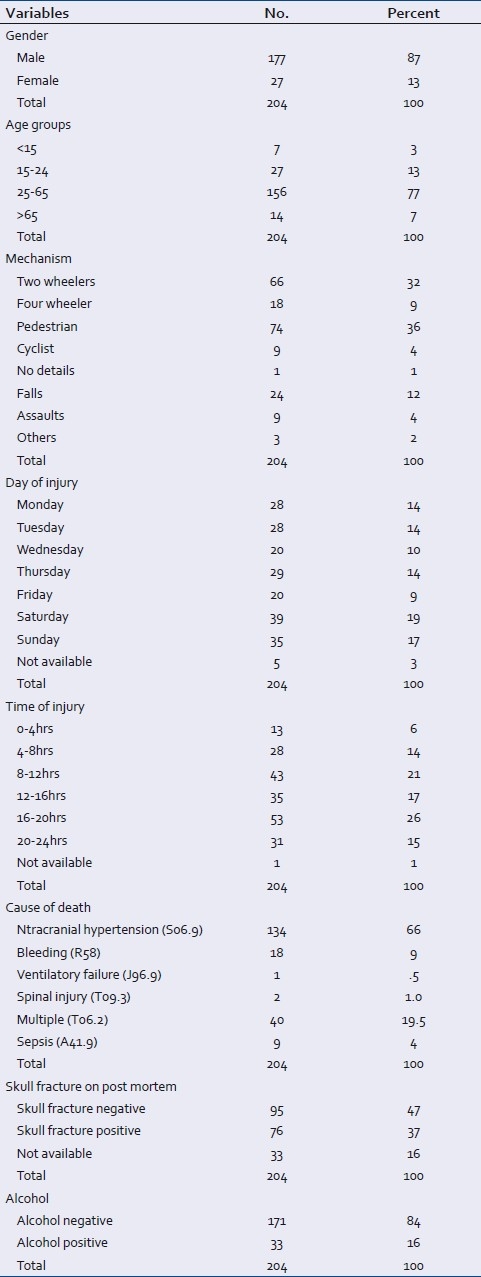

Most victims (77%) were between 25 and 65 years of age, followed by young adults between 15 and 24 y (13%); we also noted 7 percent cases above 65 y of age. In our study male: female ratio was 6.5:1. Most cases (36%) had sustained injuries over the weekends and a majority (41%) of the accidents occurred between 4 pm and 12 midnights [Table 1].

Table 1.

Clinico-demographic distribution of fatal trauma cases (n=204)

Road traffic accidents were responsible for 82 percent deaths, followed by fall from a height (12%). Most victims of road traffic accidents were either two wheel-riders or pedestrians. Among all the cases, 16 percent had evidence of being under the influence of alcohol at the time of injury [Table 1].

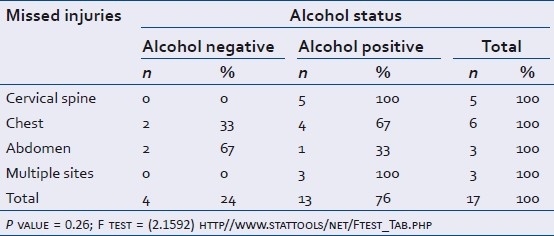

We have noted that all victims who had missed cervical spine injuries were under the influence of alcohol [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of missed injuries as per alcohol status

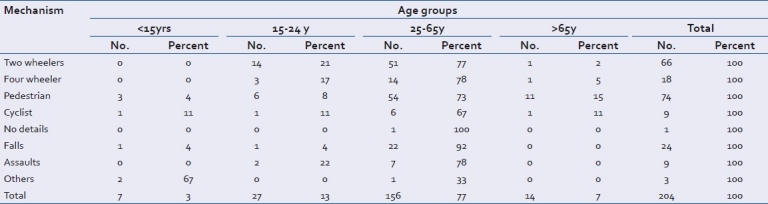

Adults between 25 and 65 y sustained most injuries (77%) while riding two wheelers, while most of those above 65 y of age (79%) sustained injuries as pedestrians [Table 3].

Table 3.

Distribution of injuries as per mechanism involved and age groups

While 44% cases reached our center directly from the site of injury, 49% cases were referred from the District headquarters/Taluk (sub districts catering to a population of 190,000) hospitals and private hospitals. Seven percent were transferred from other tertiary centers due to various reasons such as inability to afford cost of special services, or personal preference for treatment at the study hospital, etc.

Mean time interval from the time of accident to the time of admission in our center was 14.9 hours (median time being 2.5 hours). Median time to death from the time of occurrence of the event was 21.3 hours. Thirty seven percent cases had at least two changes of vehicle before arrivalto the trauma centre, thus adding to the delay. Median distance traveled from the site of injury was 30 kilometers. Extra distance traveled in and around to intermediate centers instead of coming directly to the study center ranged from 10 to 320 kilometers.

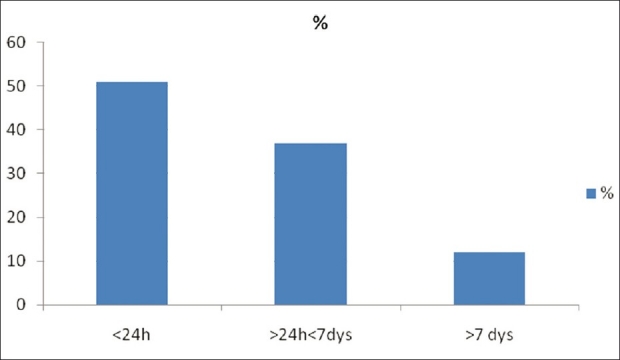

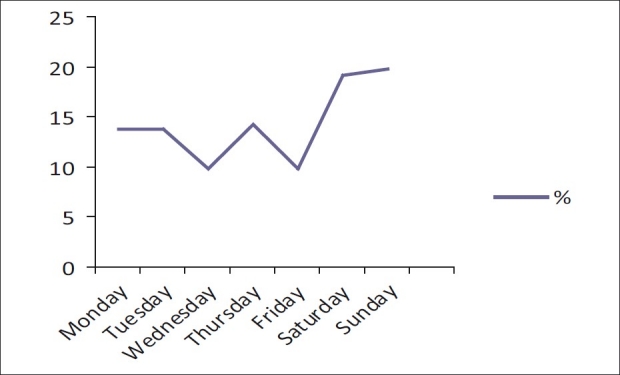

Intractable intracranial hypertension was the most (66%) common physiological cause of death. Among 76 (37%) cases that had skull fractures on post mortem, 53 were seen among two wheeler riders and pedestrians involved in a road traffic accident. Post mortem revealed missed injuries among 8 percent cases, with majority involving cervical spine and chest wall. Fifty percent of deaths occurred within 24 hours of sustaining the injury. [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Modal distribution of in-hospital deaths

DISCUSSION

In India, trauma is one of the leading causes of death and disability with 400,000 road crashes, 85,000 deaths, and 1.2 million seriously injured cases every year in India. The fatality rate is expected to escalate 5-fold by the year 2020 as projected by the World Bank.[9]

India and China that bear the maximum onslaught of this scourge, have published research of only 0.9% and 0.7%, respectively on road traffic accidents.[10] To the best of our knowledge only two papers have been presented from this high accident prone region of India.[11,12] and none on fatality. Epidemiology of trauma deaths is an important tool to assess the existing trauma care system, regardless of its maturity.

In our study male: female ratio was 6.5:1; a higher incidence ratio than 2:1 to 4:1 as reported previously.[13] Most vulnerable age groups were 25-45 y (38.24%) and 46-65 y (38.24%), the fifth and sixth decades were equally involved in our study as opposed to the 1994 study from our area.[11] We also had a significant proportion (7%) of cases above 65 y of age. This shift in age has been highlighted by Søreide in 2007.[13]

Of all the systems that people have to deal with on a daily basis, road transport is the most complex and dangerous. There were a total of 168 deaths out of 204, due to road traffic accidents in this study. The commonest mechanism was pedestrian being knocked down (44 %) and this was similar to a study in Africa, where pedestrians were most (29.5%) frequently involved.[14] Motorcyclists (39 %) were also at risk, which is higher than 32.91% reported from Jaipur.[15]

Road traffic injuries in low- and middle-income countries generally affect pedestrians, motorcyclists, and bicyclists, as opposed to four wheel drivers and occupants in high-income countries.[16] Pedestrians and cyclists are grouped as vulnerable road users. Vulnerable road users were the largest group (49 %) in our study, which is far higher than national average of 37.9% as of NCRB 2009.[7] This may be due to the fact that ours is a semi urban area where the density of non-motorized traffic would be higher. A very large proportion of deaths in the elderly above 65 y (79%) were due to trauma to pedestrians. This finding is supported in the study by Romero et al. who suggested that elderly do not have enough time to cross the roads;[17] a drawback more compounded on our chaotic roads. There are separate lanes for pedestrians and cyclists in some areas, which are invariably encroached upon by hawkers or used for parking. Lane separation for vulnerable road users should receive more emphasis by the authorities. None of the two wheeler riders wore helmets, as helmet use is not mandatory in Puducherry and the surrounding districts of state of Tamil Nadu. This result is similar to a study from Jaipur[15] and even way back to a 1994 study from our area by Jha et al.[11] Nothing has changed since then. It has been clearly proved that mandatory helmet use by motorcyclists can lead to two-thirds reduction in road trauma mortality, but has no consistent acceptance or enforcement in India.[18] Hence, helmet use needs more emphasis in the education and enforcement aspect of trauma prevention.

Different studies have showed different peak times for accidents. In our study there was steady rise of fatalities at the start of weekend [Figure 2]. There was a peak between 16 and 20 hours (26%) and a smaller peak between 8 and 12 hours (21%) comparable to National Crime Records Bureau report in 2009.[7] This is to be expected, as Puducherry is a popular weekend tourist destination especially for people from adjoining districts of state of Tamil Nadu and as far as Karnataka and Kerala. However, no significant difference was evident in incidence of vehicular accident on weekends and weekdays in the study by Kumar et al.[19] Our study finding will be helpful for traffic management, ambulance resource allocation, and to redistribute hospital personnel during weekends and peak hours during the day, to cater to the predictable increased work load in trauma. Thirty six out of two hundred and four (18%) fatalities were not due to road traffic accidents. They were mainly falls 24/36 (67%) followed by assaults 9/36 25%), blast (2/36), and work site injury (1/36).

Figure 2.

Trauma incidence on days of week

The important role of alcohol has to be highlighted in any trauma discussion. Sixteen percent were positive for alcohol, similar to a previous study from our area by Jha et al. in Pondicherry,[11] but far less than the study by Smith et al.[20] Our findings are not surprising given the fact that liquor is relatively cheap in Puducherry and there is an influx of people into the territory during weekends. This fact again calls for more education and enforcement regarding drinking and driving. Alcohol consumption not only predisposes to accidents, but we also discovered high association of alcohol positivity with missed injuries (76%). A very high proportion 14/24 (58.34%) of fatal falls was associated with alcohol positivity similar to a study by Toole[21] [Table 3].

Forty four percent of cases reached us directly from the scene of injury. Most of the referrals (37%) were from District headquarters/Taluk hospitals from the neighboring state of Tamil Nadu. A significant proportion of cases (7%) came from tertiary centers in and around Pondicherry due to various reasons ranging from personal preference to be treated in our hospital to inability to afford special services. Mean time taken to arrive was 14.9 hours, median time being 2.5 hours, and the median distance 30 kilometers. Mean delay caused from the time of accident to the time at admission in GH was 14.9 hours (median delay being 2.5 hours). This encompasses the time spent in referral centers and to travel the distance to reach our center, in keeping with the experience in other developing countries where a 6-hour delay contributed to poor outcomes.[22]

One of the causes of delay at referring centers was to perform a skull X-ray, which is a known futile investigation in head injury. This fact is reinforced in our study as 47% of fatal head injury cases were not associated with any skull fracture. Only 21% (43/204) patients could reach our hospital within the golden hour. Thirty seven percent had at least two changes of vehicle before admission to adding to the delay. Median distance traveled from the site of injury was 30 kilometers. Extra distance traveled outwards from the study center, to intermediate centers instead of coming directly to trauma center ranged from 10 kilometers up to as long as 320 kilometers. In developing economies, severely injured patients directly transferred to definitive trauma center care had better outcomes.[22] Our study emphasizes the fact that there are no available guidelines regarding the triage and disposition of trauma care.[23]

The place of first medical encounter is decided more often by the relatives, bystanders, and vehicle crew. It is only natural, that in this chaos, the patient is taken to the closest medical facility, which may be grossly inadequate to deal with serious trauma. The golden hour is thus spent without appropriate resuscitation. The trauma victim is sent from center to center with no specific medical command until he finds a place that will accept him, where, either the service is available /affordable or in an overstretched government hospital where the patient must be treated. There is no standardized protocol for the transfer of injured patients in India, a process that is well known to be potentially hazardous. This only emphasizes the fact that pre-hospital care is in a nascent stage of development in India in urban areas and grossly inadequate in smaller towns and rural areas.[24] In India, proper coordination between the trauma receiving facility and ambulance services is present in as low as 4 percent of the pre-hospital network.[23] It has been clearly proved that minimizing pre-hospital time greatly helps in reducing trauma mortality and morbidity.[25]

The commonest cause of death was head injury 134/204 (66 %). In fact, head injuries have remained the major cause of death for the last 4 decades.[26] Apart from prevention, equal focus should be placed on resources in the hospital phase for head injury . Multisystem injuries accounted for 20 percent which is higher than that of 15.8 percent reported by Singh and Dhattarwal.[27]

Consideration of the exact mechanism of injury is important. High energy trauma mandates ruling out multisystem injury, rather than waiting for injuries to manifest themselves when it would be too late. The concept of Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) has saved lives, as it helps to prioritize life threatening physiological derangements with simultaneous intervention to correct them immediately. This systematic approach has also helped in diagnosing immediate and potentially life threatening problems early, to reduce trauma mortality. Studies have shown that trauma and emergency care knowledge is grossly inadequate in India.[28] However, this situation is not hopeless. A little initiative, however small, but could make a tremendous improvement in the approach to trauma care was demonstrated in the study by Tchorz et al.[29] in which a 2-day course on initial management of trauma with a test at the end, where the general practitioners who had lower pretest scores performed as well as surgeons in the post test. Thus, even if we cannot conduct regular ATLS courses due to financial constraints, customized courses like National Trauma Management Course (NTMC) should be encouraged in our country. Through NTMC™, Academy of Traumatology (India) and International Association for Surgery of Trauma and Surgical Intensive Care (IATSIC), Switzerland have designed this course for use in India and other developing nations. The course is specifically designed taking into account Indian patients and Indian situation. Its objective is to teach those techniques particularly applicable to patients who require immediate care for major trauma, in a setting where such care is not commonly practiced or even necessarily available.[30]

The majority of deaths (87%) occurred within a week of sustaining the injury [Figure 1] in spite of surgical skills being available. This highlights the fact that along with skilled manpower we also need resources in equipment, supplies and support services. In spite of being a busy tertiary care hospital, we have developed a dedicated trauma care system quite rapidly, as we visualized the dire need. As is true of all government hospitals, resource constraints are a constant accompaniment due to the ever increasing patient load, similar to studies from Africa. Hence, it is essential that a viable private sector participation is needed in the care of the trauma patient.[31]

There are few “stand alone” trauma centers in the major cities of India. In other parts of India this concept will not be financially sustainable especially at the expense of other national health programs. Since the rate of accidents is rapidly rising, the need of the hour is to start customized trauma care programs. Pilot trauma care programs have to be integrated into the existing facilities of the public health system, especially in high accident rate areas of the country, at least for the time being, to jumpstart the development of systems.[32] These concepts once executed should be adequately monitored, evaluated and validated for maximum efficacy.

Trauma services need to be coordinated in infrastructure and human resources so that the right patient is taken to the right hospital in the right time. This calls for a lead agency at the district, state, and finally national level. In our country, government hospitals cater for all patients irrespective of origin. Our center is no exception. All these issues need to be addressed.

Strength of the study

This study was undertaken in a state public hospital, that has a large trauma load and from the area of Puducherry that historically has a high trauma load. The pre-hospital care issues had been highlighted. The population at risk was delineated and the in-hospital modal death pattern has been emphasized. This study identifies areas that can be rectified without much translocation of funds and other resources.

Limitations of the study

This is a single-center study. There were many more trauma victims who were dead on arrival at the emergency room or brought directly for postmortem to our center. There is always a probability of Berkson's bias and external validity of the outcome of study is limited as this was a hospital based study with our limited resources. Lastly, alcohol status was made based on surrogate markers instead of purely Blood Alcohol Level (BAC) analysis; patients who came late to us would have been alcohol false negative. By this endeavor we have only managed to scratch the surface of the problem of trauma fatalities in our study area.

Future directions of study

This study can be seen as one of the scenarios of trauma problems in rapidly urbanizing areas in India. Government hospitals ultimately bear the major burden of the seriously injured persons at least during the acute and resuscitative phase of trauma. This study can be the impetus to motivate committed professionals in the trauma specialty to help in the organization of available facilities and to upgrade existing facilities for a better response to injury, which should not be different from other public heath responses.

In conclusion, the problem of trauma needs to be addressed aggressively in India. The world has accepted the evidence that mature trauma systems have reduced the mortality and morbidity of trauma.[33] It is impractical and even unwise to accept ad verbatim all the guidelines of a mature trauma system for implementation here. However, we should customize our very own guidelines on well tested templates keeping in mind our economic, manpower, training, and political resources.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge contributions of Dr. R Balaraman Head, Department of Forensic Medicine and Dr. S Diwakar, Specialist, Department of Forensic Medicine, Indira Gandhi Government Hospital and Postgraduate institute, Puducherry, in our study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peden M, McGee K, Sharma G. A graphical overview of the Global Burden of Injuries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Last accessed on 2011 May 26]. The injury chart book. Available from: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/924156220x.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshipura MK, Shah HS, Patel PR, Divatia PA. Trauma care systems in India-An overview. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2004;8:93–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention, WHO/World Bank. 2004. [Last accessed on 2011 May 26]. Available from: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/9241562609.pdf .

- 4.West JG, Cales RH, Gazzaniga AB. Impact of regionalization.The orange county experience. Arch Surg. 1983;118:740–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1983.01390060058013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mock CN, Jurkovich GJ, nii-Amon-Kotei D, Arreola-Risa C, Maier RV. Trauma mortality patterns in three nations at different economic levels: Implications for global trauma system development. J Trauma. 1998;44:804–14. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NIHFW, Munirka, New Delhi, India: 2006. Oct 27th, [Last accessed on 2011 May 26]. Recommendations for Pre-hospital trauma care in India. Report of a 2 day National consultation on Pre Hospital Trauma Care in India on 26th. Available from: http://www.whoindia.org/LinkFiles/Diability,_Injury_Prevention_and__Rehabilitation_Pre_hospital_trauma_care.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Crime Bureau Report 2009. [Last accessed on 2011 May 26]. Available from: http://www.ncrb.gov.in/CDADSI2009/accidental-deaths-09.pdf .

- 8.Medical Dictionary. [Last accessed on 2011 May 26]. Available from: http://www.merriamwebster.com/medlineplus/Trauma .

- 9.The World Health Report 2003. Shaping the future. [Last accessed on 2011 May 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2003/en/whr03_en.pdf .

- 10.Borse NN, Hyder AA. Call for more research on injury from the developing world: Results of a Bibliometric analysis. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:321–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jha N, Srinivasa DK, Roy G, Jagdish S. Injury pattern among road traffic accident cases: A study from South India. Indian J Community Med. 2003;2:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganapathy K, Dongre AR, Mahalakshmy T. Epidemiology of injury in rural Pondicherry. J Inj Violence Res. 2011;3:62–7. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v3i2.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Søreide K, Krüger AJ, Vårdal AL, Ellingsen CL, Søreide E, Lossius HM. Epidemiology and contemporary patterns of trauma deaths: Changing place, similar pace, older face. World J Surg. 2007;31:2092–103. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinwall D, Befrits F, Naidoo SR, Hardcastle TC, Eriksson A, Muckart DJ. Deaths at a level 1 Trauma Centre: A clinical finding and post-mortem correlation study. Injury. 2012;43:91–5. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathak A, Desania NL, Verma R. Profile of Road Traffic Accidents and Head Injury in Jaipur (Rajasthan) J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2008;1:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nantulya VM, Reich MR. The neglected epidemic: Road traffic injuries in developing countries. BMJ. 2002;324:1139–41. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7346.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham CU, Kenny RA. Do older pedestrians have enough time to cross roads in Dublin? A critique of the Traffic Management Guidelines based on clinical research findings. Age Ageing. 2010;1:80–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald M, Dewan Y, O’Reilly G, Mathew J, McKenna C. India and the management of road crashes: Towards a national trauma system. Indian J Surg. 2006;68:226–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar A, Lalwani S, Agrawal D, Rautji R, Dogra TD. Fatal road traffic accidents and their relationship with head injuries: An epidemiological survey of five years. Indian J Neurotrauma. 2008;2:63–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith GS, Branas CC, Miller TR. Fatal non traffic injuries involving alcohol: A metaanalysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:659–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Toole O, Mahon C, Lynch K, Brett FM. Is the contribution of alcohol to Fatal Traumatic Injuries being underestimated in the acute Hospital setting? Ir Med J. 2009;102:223–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheddie S, Muckart DJ, Hardcastle TC, Den Hollander D, Cassimjee H, Moodley S. An audit of a new level 1 Trauma Unit in urban KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Med J. 2011;101:176–8. doi: 10.7196/samj.4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joshipura MK, Shah HS, Patel PR, Divatia PA, Desai PM. Trauma care systems in India. Injury. 2003;34:686–92. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(03)00163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sethi AK, Tyagi A. Trauma Untamed as yet. Trauma Care. 2001;11:89–90. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mock C. Strengthening prehospital trauma care in the absence of formal emergency medical services. World J Surg. 2009;33:2510–1. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh B, Palimar V, Arun M, Mohanty MK. Profile of trauma related mortality at Manipal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2008;23:393–8. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v6i3.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh H, Dhattarwal SK. Pattern and distribution of injuries in fatal road traffic accidents in Rohtak (Haryana) J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2004;26:20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S, Agarwal AK, Kumar A, Agarwal GG, Chaudhary S, Dwivedi V. A study of knowledge, attitude and practice of hospital consultants, resident doctors and private practitioners with regard to pre-hospital and emergency care in Lucknow. Indian J Surg. 2008;70:14–8. doi: 10.1007/s12262-008-0003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tchorz KM, Thomas N, Jesudassan S, Kumar R, Chinnadurai R, Thomas A, et al. Teaching trauma care in India: An educational pilot study from Bangalore. J Surg Res. 2007;142:373–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Trauma Management course (NTMC) [Last accessed on 2011 Sept 24]. Available from: http://www.indiatrauma.org/ntmc.htm .

- 31.Hardcastle TC. The 11 P's of an Afrocentric Trauma System. S Afr Med J. 2011;101:160–2. doi: 10.7196/samj.4578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Razzak JA, Kellermann AL. Bull World Health Organ. 11. Vol. 80. Geneva: 2002. Nov, [Last accessed on 2011 May 26]. Emergency medical care in developing countries: Is it worthwhile? Available from: http://www.scielosp.org/pdf/bwho/v80n11/80n11a11.pdf . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demetriades D, Murray J, Charalambides K, Alo K, Velmahos G, Rhee P, et al. Trauma Fatalities: Time and location of hospital deaths. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]