Abstract

All over the world, pediatric trauma has emerged as an important public health problem. It accounts for the highest mortality in children and young adults in developed countries. Reports from Africa on trauma in the pediatric age group are few and most have been single center experience. In many low-and middle-income countries, the death rates from trauma in the pediatric age group exceed those found in developed countries. Much of this mortality is preventable by developing suitable preventive measures, implementing an effective trauma system and adapting interventions that have been implemented in developed countries that have led to significant reduction in both morbidity and mortality. This review of literature on the subject by pediatric and orthopedic surgeons from different centers in Africa aims to highlight the challenges faced in the care of these patients and proffer solutions to the scourge.

Keywords: Africa, challenges in management, pediatric trauma

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric trauma is a common cause of morbidity and mortality.[1] It is the most likely cause of death in children who survive the first five years, when infectious diseases are the leading cause of death; and this continues till the fourth decade of life.[2] In some countries, the mortality from pediatric injuries is more than 50%.[3] In many low-and middle-income countries, the death rates from trauma in the pediatric age group exceed those found in developed countries .[4] Much of this mortality is preventable by implementing an effective trauma system and developing interventions that have been implemented in developed countries and led to significant reduction in both morbidity and mortality.[5] The challenges of pediatric trauma in Africa and particularly in sub-Saharan Africa will be highlighted by considering (i) the burden of trauma among pediatric populations, (ii) the role of sociopolitical will in addressing the problem, (iii) challenges of developing trauma centers in developing economies, (iv) the funding of such centers, (v) the challenge of personnel training as well as (vi) the challenge of educating the public; that injuries are preventable public health problems that should be addressed as such and finally proffer the possible solutions to these challenges.[6]

The burden of trauma in Africa

Africa has been described to be the least healthy place in the world to live.[7] The infant and maternal mortality rates in African countries are among the highest in the world.[8] The average annual per capita income is in the range of $400 or less.[9] As far back as 2 decades ago, about 36% of the urban population and 75% of the rural population live below the absolute poverty line.[2] The average per capita expenditure spent on health in most sub-Saharan African countries is less than $14 per annum .[2]

Against this background is the attempt by most governments to industrialize their nations with the attendant increase in the influx of motorized machines, cars and motorcycles. This has increased the incidence of trauma in these countries including pediatric trauma, and trauma is fast becoming a leading cause of death among the pediatric age group of 0 – 15 years.[2,10] This epidemiological profile is similar to the situation in most high-income countries of the world, where injuries are the most common cause of death in this age group.[11]

The exact scope of the burden of pediatric trauma in Africa is difficult to ascertain, as there are very few reports about this emerging public health problem. Most of the available records are from hospital-based data and inference from such reports is difficult to extrapolate to the general population.[1] One of such studies from southwest Nigeria showed that 9% of emergency room admissions were due to trauma in the pediatric age group.[12] Another study from Ethiopia showed an injury rate of 4.8% among 7055 hospital admissions over a five-year period.[13] Reports from certain areas of the continent have similar epidemiological profile as the developed countries of the world. For example, reports from Southern Africa and Mediterranean countries show that trauma is the most common cause of death in the age bracket of 0 – 15 years.[10]

Challenge of trauma registries

As noted earlier, records on pediatric trauma have been very poor and have therefore made the need for pediatric trauma registry inevitable. The registry concept is an accepted tool of epidemiology, and has been widely used in cancer epidemiology.[14] A trauma registry offers a means of collecting continuous, standardized injury data that offers advantages over discrete means of injury surveillance, such as retrospective or prospective data collection.[15] Trauma registry records will offer evidence-based capacity building outcomes that will guide subsequent treatment and resource allocation, an important consideration for a resource-poor continent like Africa.[15] While such systems have been widely established - and have proved to be very useful - in developed countries, their application in developing countries has been hindered by issues of cost, complexity and political will.[16] However, numerous studies from all over the world have shown that trauma registries can be incorporated into existing trauma care framework in resource-poor settings.[13,15–17]

In Africa, for example, an injury surveillance system incorporating two hospitals was established in Kampala. It is a one-page registry form, which permitted injury severity measurement using the locally developed Kampala trauma score. This mode has been adapted for use in other parts of Africa.[13,17] The data collected in such registries can vary; for example, the aforementioned Kampala registry form is a 19-item document, while Nwomeh and Ameh in Zaria, Nigeria, used a 10-item registry form.[18] It is suggested that firstly, a retrospective study of the hospital record be done to identify what added information will be required of the trauma registry.[15] An existing registry form can then be adapted to the needs of the hospital .[17] In general, the data recorded should include variables from the following categories: demographics, mechanism of injury and related location and circumstances, prehospital information, vital signs, diagnoses, level of severity of injury as measured by an appropriate trauma score, procedures performed, including length of stay and outcomes. It is suggested that data from hospitals in the same region can be pooled into a regional and then national trauma registry. Even when the data are not pooled, information gained from individual trauma centers are often scalable to regional, state or even national levels. Such centers should have well computerized systems for storing and analyzing the collected data.[19,20]

Much proprietary software which can be run either on desktop PCs or networks exists for this purpose. Many of these are prohibitively expensive for many hospitals in Africa, but an easy to use, completely free alternative is Epiinfo developed by the centers for disease control and prevention (CDC). This was used in the development of the Kampala trauma score.[17] OpenOffice Base is a part of the OpenOffice application suite which is similar to Microsoft Access® that can be used by hospitals and governments for developing and maintaining trauma databases.[21]

As many authors have noted, it is time for Africa to arise to the challenge of publishing and documenting her experience in the area of trauma including pediatric trauma.[22] It is hoped that such centers will alleviate the suffering of researchers in this interesting and important field of medical research by making data available and more importantly, aid the formulation, monitoring as well as appraisal of policies aimed at improving the health statistics in this area.

The other challenge faced by the African researcher is trauma academic productivity. It has been estimated that researchers in Diaspora produce 4.5 times more publications than their counterpart at home.[23] One of the factors responsible for this is access to journals and databases. HINARI is an online portal with more than 5000 journals that researchers in low-income countries (LIC) and middle-income countries (MIC) can access[24] Finally the internet provides a unique and relatively easy and inexpensive way for researchers living in different parts of the world to collaborate and pool resources together in ways not hitherto available.

Challenges of pediatric trauma care

Trauma is fast emerging as a serious public health problem.[1] The management of victims of trauma, either from road traffic injuries (RTI), falls, civil strife and wars, which are not uncommon in Africa, requires functional trauma care systems. Important components of such a system include pre-hospital care, initial hospital care, inter-hospital referral services, and rehabilitation. The goal of such a system in the prehospital setting is to combine minimal transport time with adequate resuscitation.[25] Better surgical and rehabilitative care in hospitals build on the prehospital care to ensure improved outcomes. These hospitals evolved in most high-income countries (HIC) to trauma centers, which are tertiary level hospitals established to provide care for seriously injured patients. Such systems are resource intensive, costly to maintain and difficult to staff. For example, an average level one trauma center in the USA may have up to 80 or more specialists, including orthopedic surgeons, trauma specialists, general surgeons, anesthetists and neurosurgeons; more specialists than are found in some countries in Africa.[25] For this reason alone, such a model may not be suitable for the LIC of sub-Saharan Africa.[6] The other reason might be that, given the different contextual factors such as injury type (penetrating vs. blunt), prehospital time, and socio-geographical indices, the model might work differently in the African setting. This point is buttressed by the fact that the model performed less efficiently in Britain than in the USA.[26] Thus we need to carefully evaluate medical technologies and practices, and then adapt them to our need, rather than importing them indiscriminately. Most African countries have a three-tiered structure, comprising of a primary, secondary and tertiary health centers. Because the prehospital care system is so poorly developed, all injured patients are taken directly to the nearest hospital. This leads to prolonged prehospital time, high incidence of case mix and inter-hospital referral rate. The other problem is that the existing system leads to waste of resources, because patients with minor injuries are treated at tertiary centers when they could have been competently treated in lower tiered hospitals .[20,25] There is a need for a system of low cost, easily affordable and sustainable pre-hospital care system that can be integrated into the existing framework of healthcare system in Africa. It has been successfully demonstrated in Ghana that prehospital care for road crash victims could be improved by training commercial drivers.[27] Other low-cost models include basic trauma life support (BTLS) training of first responders consisting of members of the police, road traffic marshals, Red Cross and other youth organizations, as well as volunteers in the community. Though there is paucity of literature on the effectiveness of first responders in improving trauma outcome in a civil population, some studies have demonstrated their effectiveness in warfare.[28,29] Because the responders may lose their skills unless they are put to frequent use, lay responders are likely to be successful where the burden of injuries and other emergencies is high. There are many countries in Africa with inter tribal conflicts and more recently, the wave of protests against the state in Northern Africa present opportunities to hone such skills. The third option is the placement of ambulance teams at well-placed dispatch sites in urban centers. This model has recently been introduced in Nigeria by the government of Lagos, the commercial center and largest metropolis in the country.

Several studies from Africa have shown that the majority of Africans with traumatic injuries patronize traditional healers before ever considering orthodox practitioners. Many of these studies showed that majority of amputations among children were as a result of complications from traditional bone setters.[30–33] There are indications that this situation will not change soon because existing evidence suggests that exposure and education has minimal impact on decisions to patronize traditional healers. Therefore there is an urgent need to incorporate traditional bone setters (TBS) into existing primary healthcare system in the country. Eshete in Ethiopia showed that giving instructional courses leads to TBS significant reduction of gangrenous limbs and amputation within two years.[34] Omololu[35] in Nigeria developed a training algorithm that can be used for sustaining development, training and monitoring of TBS while Onuminya[36] has shown how TBS can be integrated with minimal friction into existing PHC framework in African countries.

Finally, there is a clear need to strengthen pediatric accident and emergency training among health personnel. Studies from both Ghana and Trinidad and Tobago had shown continuing education in trauma to non specialist clinicians to be cost effective[27,37] Lastly, there is a need to develop pediatric trauma as a specialty. The two postgraduate medical colleges, in West Africa, offer specialty training in pediatric surgery but not in trauma. The present trauma training is insufficient, because it is offered as a subsidiary of orthopedics. While such training may be available in other parts of Africa, for example South Africa;[20] funding to support surgeons for such program from other parts of Africa should be made available by Governments of regions where such training is not available.

Challenge of funding

Health is wealth, so the saying goes. However, wealth is also necessary in order to get good health. There is a great challenge to acquire funding for health institutions. This is the bane of the health situation in many African countries. It is known that the per capita health expenditure in Africa is less than $14.00 per annum.[2] Most African countries spend less than 5% of the annual budget on health, a far cry from the World Health Organization minimum of 8%. This is a reflection of the weak political will of most African nations in implementing health policies that are beneficial to the majority of their population.[2]

More than in any other part of the world, funding for pediatric trauma care and research has being neglected.[38] A study done in Tanzania showed that even though injuries were responsible for 30% of all pediatric admissions (second only to malaria at 32%), it received no research or treatment grants from NGOs and UN organizations .[38] Instead, most research funds were directed to malnutrition, malaria and HIV/AIDS. Yet, guidelines for priority setting in resource allocation in healthcare expenditure already exist; in 1996, the WHO Ad Hoc Committee for Health Research Relating to Future Intervention Options recommended the following five steps:[39]

Sizing of the disease burden

Identifying the reasons why the disease burden persisted

Assessment of the adequacy of the current scientific knowledge base

Assessment of the cost-effectiveness of potential interventions and the probability of successful development of new tools

Measuring the adequacy of the current level of ongoing research and funding.

Thus for equity in healthcare resource allocation, funding appropriate to its level of importance must be provided for research in pediatric trauma, to generate data, plan prevention and control of the problem. Such preventive and control measures should be well adapted to our environment, and will not just be a “transfer of technology” from the developed nations of the world

Challenge of personnel training

There is chronic shortage of qualified trauma and pediatric surgeons in Africa. In 2000, there were less than 50 pediatric surgeons in sub - Saharan Africa,[2] and almost all of them worked in big urban hospitals. In most countries in Africa, pediatric trauma patients are treated by generalists, general surgeons with no trauma or pediatric surgical training or non physicians.[2,38] Therefore, an urgent need exists for increased personnel training in pediatric trauma. Training medical personnel is very expensive, time consuming and not easily affordable to resource-poor countries of sub-Saharan Africa.[40] In some countries outside of Africa, non-physician healthcare providers-and in some cases, lay persons- have been trained to provide essential trauma care.[41] For example, in Cambodia, training volunteer laypersons to recognize severely injured persons, and provide basic first aid and wound care decreased mortality from land mine injuries from 40% to 9%.[28] There is also a belief that musculoskeletal trauma training content of medical school curriculum is deficient in many areas of the world, Africa inclusive.[41] The WHO Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care was aimed at improving emergency surgical, trauma and obstetric care at the district hospital level.[42] This program has begun to be implemented in African countries, including Ghana, Mozambique and Ethiopia. Another program recently introduced by WHO is the MENTOR-VIP program which sought to develop human resource capacity in injury prevention by providing mentoring opportunities to relevant professionals.[43] It is a free 12-month working relationship between a junior practitioner and a more experienced person in the field .[43]

However, non specialist and non physician healthcare providers can only cater adequately to patients with minor to moderately severe injuries; there is still a desperate need for the training of pediatric and trauma surgeons in sub-Saharan countries to manage severely injured patients. Thus if trauma systems and trauma centers were to be well developed and staffed, then medical personnel training would become very important both at the specialist level and less specialized cadres.

The final challenge of training in pediatric trauma care in sub-Saharan Africa is the pernicious effect of brain drain on the continent's human resource component of capacity. Brain drain, which has been defined as the migration of health personnel in search of better standard of living and quality of life, higher salaries, access to advanced technology and more stable political conditions in different places worldwide, is responsible for taking 23,000 African health professionals to high-income countries each year.[44] While it would be difficult or impossible to stem this trend, there are indications that such brain drain can be made beneficial.[44] In 2006, about $300 billion-nearly three times the world's foreign aid- was remitted home by migrant workers living abroad.[45] A percentage of these earnings could be invested in research and development so that opportunities for highly skilled and educated individuals can improve at home.[44] Finally expatriate physicians can contribute their skill and expertise to the teaching and training of their fellow physicians back at home[44] as well as contribute to patients’ management[46] either directly or through telemedicine.[44]

The challenge of injury prevention

Compared to the USA, with an annual $2500 per capita expenditure on health, most African countries spend barely more than $5 dollars per capita annually. Also, the trimodal pattern of post traumatic death showed that approximately 50% of injury-related deaths occur early and are usually not amenable to treatment. In the light of these facts, prevention appears to be the most cost-effective method for dealing with the problem of injuries .[47] With an unintentional injury rate of 53·1 per 100 000, Africa is the most dangerous place in the world for a child.[48] The most common injuries are road traffic crashes, falls, burns and accidental poisoning.[2,38] Children are not simply young adults, but are a group with specific attributes that make them especially vulnerable to injuries. Some of the risk factors for pediatric injuries include poverty, frequent family household moves, single-parent households, household crowding, other siblings, child aggression, impulsiveness, and hyperactivity; poor maternal mental/physical health, marital discord and child abuse/neglect.[49] To combat these problems, the four frame model of injury prevention can be adopted. These include:

The three Es of intervention which are (i) education to influence behavior and raise awareness of injury risk e.g. injury prevention messages conveyed through the mass media and through religious organizations; (ii) engineering to reduce risk e.g. provision of speed bumps and (iii) enforcement through legal regulation or sanctions against behavior or actions likely to increase risk of injuries e.g. residential speed limit laws.[50]

The Haddon matrix in which injuries are visualized as the result of interactions between three factors: the host, agent (vehicle) and the environment. These interactions occur in three phases: the pre-event, event and the post event. In a fall from a height, for example, the table top from which the child falls is the vector for transferring mechanical energy (agent) to an unsupervised (environment) child (host) to produce a fracture. In this scenario, the pre-event phase condition will include the height of the table, hardness of the ground (is there rug on the floor?); the event condition will be whether or not the child was shoved off the table and the post event phase will be the speed and quality of treatment offered.[51]

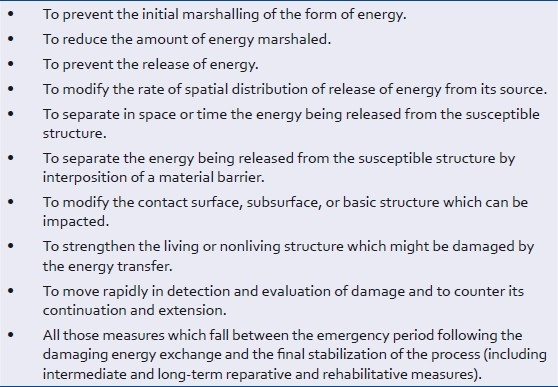

The ten Haddon strategies for injury intervention designed to interfere with energy transfer or injury process [Table 1].[52]

Table 1.

Haddon strategies for injury intervention

Passive versus active interventions. Passive interventions occur when no action is required to be taken by an individual before a safety device deploys e.g. car airbags; while an active intervention requires that an individual take active step to deploy or use the safety device e.g. wearing seat belts. The most effective interventions in pediatric trauma are passive interventions.[53]

Crashes on the roads are responsible for more deaths and severe injuries than any other among African children. Most are due to pedestrian injuries, with risk factors which include street trading, road crossing, school resumption and closure, sending children on errands and proximity of school to home. Simple cost effective methods that have been found useful include the use of speed breakers such as speed bumps and rumpled zone, adolescent pedestrian road safety education and enforcement of traffic rules. Countries should also enact and enforce laws governing the use of child vehicle occupant restraints. A major challenge in sub-Saharan Africa is to overcome the fatalistic perception that road crashes are inevitable, and are prices to pay for development. It is in this regards as well as other areas of pediatric injury prevention that initiatives by NGOs like the Child Accident Prevention Foundation of Southern Africa (CAPFSA),[54] International Safe Community Initiative[55] and Road Safety Nigeria[56] become important.

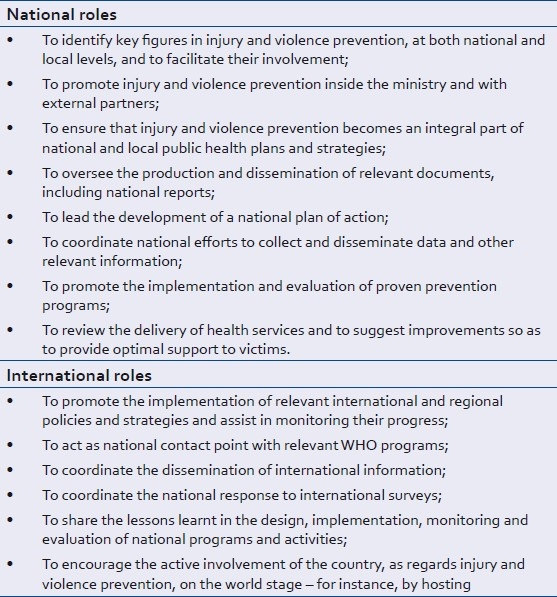

Challenge of sociopolitical will

The decreasing death rates from injuries witnessed in most developed countries are because the government in these countries has recognized the need to develop coordinated injury prevention programs based on sound epidemiologic principles and the raised awareness among the population about the possibilities of accident prevention. The singular, most important factor in reducing injury and injury mortality remains the political will to back up policies aimed toward this end. The wheel needs not be re-invented, as most of the measures needed to combat the risk factors have already been proven in high-income countries. African governments can just provide the necessary framework that would allow for the selection, adaptation and implementation of measures that are appropriate to the local setting.[57] In recognizing this role, the WHO has identified several areas by which governments, through the Ministries of Health, can develop an effective policy of injury prevention [Table 2].[58] There are, however, obstacles along the way. Most African nations are impoverished and shackled by their burden of external debt while there is a severe shortage of tertiary trained health experts and sometimes widespread corruption; all these factors have impaired governments’ ability to adopt the measures that should have been adopted to stem the rising injury epidemics. The epidemic of pediatric trauma can only be curbed if successive governments show their commitment in doing so. Many of the challenges cannot be corrected without a government willing to effect changes and commit funds to research and training.

Table 2.

The role of Government in injury prevention

The way forward

There is a need to begin to utilize new and emerging technologies which have been proven useful in other aspects of healthcare. One such technology is telemedicine, which has been employed in different parts of the world. For patients with minor injuries in remote, rural and inaccessible locations, it offers the potential to provide urgent or emergency treatment without the need for the patient to travel long distances and the avoidance of the associated expense and danger.[59]

Most countries in Africa now have well-established mobile telephony systems that can be employed for providing voice and data based telemedicine consultation between non specialist healthcare providers in remote areas and specialists in urban centers. For example, in peripheral hospitals, healthcare practitioners equipped with camera phones can take high-resolution still and video images of patients or/and their X-rays and such can be sent by multimedia messaging service (MMS) to specialists for consultation and treatment. Such systems have been found to be useful in two types of situations: (1) In remote, inaccessible locations, such as mountains, where there is no alternative; (2) during mass disasters when it may be impossible for transfer to be arranged, it offers “a way of staffing low volume hospitals with qualified emergency physicians”.[60] Lastly the suggested solutions by Hardcastle[6] in the South African context can be modified by other African countries to suit local needs.

CONCLUSION

From the foregoing discussion, the problems of pediatric trauma are centered on, but not limited to, a lack of strong political will to control this major, but hidden public health problem. Pediatric trauma needs to come out of the closet. Therefore, urgent need exists for pediatric surgeons as well as all other concerned healthcare professionals to intensify their research efforts on the epidemiology of the problem which could serve as a logical basis for advocacy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nwomeh BC, Ameh EA. Pediatric trauma in Africa. Afr J Trauma. 2003;1:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bickler SW, Rode H. Surgical services for children in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:829–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meel BL. Mortality of children in the Transkei region of South Africa. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2003;24:141–7. doi: 10.1097/01.PAF.0128052262.54227.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Technical Report Series 600. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1976. World Health Organization. New trends and approaches in delivery of maternal and child care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobusingye OC. Why poor countries can not afford to ignore road safety. Afr J Trauma editorial. 2004;2:6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardcastle T. The 11 P's of an Afrocentric trauma system for South Africa time for action! S Afr Med J. 2011;101:160–162. doi: 10.7196/samj.4578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Washington (DC): World Bank; 1994. World Bank. Better health in Africa: Experiences and lessons learned. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vol. 22. Washington, D.C: USAID, Bureau for Africa; 1986. United States. Agency for International Development [USAID]. Bureau for Africa: Child survival strategy, 1987-1991; p. 33. (Africa Bureau Sector Strategy Child Survival Action Program [CSAP] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross national income per capita 2007, Atlas method and PPP. [Last accessed on 2009 Jan]. Available from: http://www.siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/GNIPC.pdf .

- 10.Cywes S, Kibel SM, Bass DH, Rode H, Miller AJ, De Wet J. Pediatric trauma care. S Afr Med J. 1990;78:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivara FP. Epidemiology of childhood injury I.Review of current research and presentation of a conceptual framework. Am J Dis Child. 1982;136:399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adesunkanmi AR, Oginni LM, Oyelami AO, Badru OS. Epidemiology of childhood injury. J Trauma. 1998;44:506–12. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199803000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gediu E. Accidental injuries among children in Northwestern Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 1994;71:807–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooke EM. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1974. The current and future use of registers in health information systems. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz CR, Ford HR, Cassidy LD, Shultz BL, Blanc C, King-Schultz LW, et al. Development of a hospital-based trauma registry in haiti: An approach for improving injury surveillance in developing and resource-poor settings. J Trauma. 2007;63:1143–54. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815688e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charters AC, Bailey JA. Experience with a simplified trauma registry: Profile of trauma at a university hospital. J Trauma. 1979;19:13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobusingye OC, Lett RR. Hospital-based trauma registries in Uganda. J Trauma. 2000;48:498–502. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200003000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nwomeh BC, Lowell W, Kable R, Haley K, Ameh EA. History and development of trauma registry: Lessons from developed to developing countries. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:32. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-1-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cales RH, Bietz DS, Heilig RW., Jr The trauma registry: A method for providing regional system audit using the microcomputer. J Trauma. 1985;25:181–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardcastle TC, Steyn E, Boffard K, Goosen J, Toubkin M, Loubser A, et al. Guideline for the assessment of trauma centres for South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2011;101:189–94. doi: 10.7196/samj.4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The open office base. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec]. Available from: http://www.openoffice.org/product/base.html .

- 22.Solagberu BA. The future of trauma research in and from Africa is open and unlimited (editorial 1) Afr J Trauma. 2004;2:5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mock C, Meena NC. The global burden of musculoskeletal injuries: Challenges and solutions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2306–16. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0416-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.HINARI Access to Research. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hinari/en/

- 25.Sethi D, Aljunid S, Sulong SB, Zwi AB. Injury care in low and middle income countries: Identifying potential for change. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2000;7:153–67. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholl J, Turner J. Effectiveness of a regional trauma system in reducing mortality from major trauma: Before and after study. BMJ. 1997;315:1349–54. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7119.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mock CN, Quansah R, Addae-Mensah L, Donkor P. The development of continuing education for trauma care in an African nation. Injury. 2005;36:725–32. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Husum H, Gilbert M, Wisborg T, van Heng Y, Murad M. Rural prehospital trauma systems improve trauma outcome in lowincome countries: A prospective study from North Iraq and Cambodia. J Trauma. 2003;54:1188–96. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000073609.12530.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pretto EA, Begovic M. Emergency medical services during the siege of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina: A preliminary report. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1994;9(2 Suppl 1):S39–45. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00041170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olasinde AA, Oginni LM, Bankole JO, Adegbehingbe OO, Oluwadiya KS. Indications for amputations in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2002;11:118–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omololu B, Ogunlade SO, Alonge TO. The complications seen from the treatment by traditional bonesetters. West Afr J Med. 2002;21:335–7. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v21i4.28014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onuminya JE, Obekpa PO, Ihezue HC, Ukegbu ND, Onabowale BO. Major amputations in Nigeria: A plea to educate traditional bone setters. Trop Doct. 2000;30:133–5. doi: 10.1177/004947550003000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker G. Traditional bone setter's gangrene. Int Orthop. 1999;23:192. doi: 10.1007/PL00021042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eshete M. The prevention of traditional bone setter's gangrene. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:102–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Omololu AB, Ogunlade SO, Gopaldasani VK. The practice of traditional bonesetting: Training algorithm. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2392–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onuminya JE. The role of the traditional bonesetter in primary fracture care in Nigeria. S Afr Med J. 2004;94:652–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ali J, Adam R, Butler AK, Chang H, Howard M, Gonsalves D, et al. Trauma outcome improves following the advanced trauma life support program in a developing country. J Trauma. 1993;34:890–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199306000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mhando S, Lyamuya S, Lakhoo K. Challenges in developing paediatric surgery in Sub-Saharan Africa. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22:425–7. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1669-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Investing in health research and development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. Ad Hoc Committee on health research relating to future intervention options. [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization: World Health Statistics. 2007. [Last accessed on 2009 Jan]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat2007_5healthsystems_hrh.pdf .

- 41.Fisher RC. Musculoskeletal trauma services in mozambique and Sri Lanka. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2399–402. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0365-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mock C, Lormand JD, Goosen J, Joshipura M, Peden M. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Guidelines for essential trauma care. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hyder AA, Meddings D, Bachan AM. MENTOR-VIP: Piloting a global mentoring program for injury and violence prevention. Acad Med. 2009;84:793–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a407b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dodani S, LaPorte RE. Brain drain from developing countries: How can brain drain be converted into wisdom gain? J R Soc Med. 2005;98:487–91. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.11.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Migrant workers worldwide sent home more than US$300 billion in 2006, new study finds, Inter-American Development Bank [Online] [Last accessed on 2011 Mar 05]. Available from: http://www.ifad.org/media/press/2007/44.htm .

- 46.Saravia NG, Miranda JF. Plumbing the brain drain. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:608–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mock CN, Adzotor E, Denno D, Conklin E, Rivara F. Admissions for injury at a rural hospital in Ghana: Implications for prevention in the developing world. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:927–31. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hyder AA, Peden M, Krug E. Child health must include injury prevention. Lancet. 2009;373:102–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fallat ME, Costich J, Pollack S. The impact of disparities in pediatric trauma on injury-prevention initiatives. J Trauma. 2006;60:452–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196936.72357.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Widome MD. Remembering as we look ahead: The three E's and firearm injuries. Pediatrics. 1991;88:379–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haddon W., Jr A logical framework for categorizing highway safety phenomena and activity. J Trauma. 1972;12:193–207. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haddon W., Jr Energy damage and the ten countermeasure strategies. J Trauma. 1973;13:321–31. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197304000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DA.Doll LS, Bonzo SE, Mercy JA, Sleet DA. New York: Springer; 2007. Handbook of injury and violence prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Child accident prevention foundation of Southern Africa. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec]. Available from: http://www.childsafe.org.za/

- 55.Safe Community Network Members. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec]. Available from: http://www.phs.ki.se/csp/who_safe_communities_network_en.htm .

- 56.Road safety in Nigeria. [Last accessed on 2009 Dec]. Available from: http://www.roadsafetynigeria.com/

- 57.Samuel N, Forjuoh SN. Traffic-related injury prevention interventions for low-income countries. Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2003;10:109–18. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.1.109.14115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krug EG, Sminkey LA, Harvey A, Kellerman GA. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Preventing injuries and violence: A guide for ministries of health. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benger J. A review of minor injury telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 1999;5(Suppl. 3):S3:5–13. doi: 10.1258/1357633991933666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brennan JA, Kealy JA, Gerardi LH, el-Khoury GY. Telemedicine in the emergency department: A randomized controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare. 1999;5:18–22. doi: 10.1258/1357633991932342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]