Abstract

Introduction:

Physician burnout has received considerable attention in the literature and impacts a large number of emergency medicine physicians, but there is no standardized curriculum for wellness in resident education. A culture change is needed to educate about wellness, adopt a preventative and proactive approach, and focus on resiliency.

Discussion:

We describe a novel approach to wellness education by focusing on resiliency rather than the unintended endpoint of physician burnout. One barrier to adoption of wellness education has been establishing legitimacy among emergency medicine (EM) residents and educators. We discuss a change in the language of wellness education and provide several specific topics to facilitate the incorporation of these topics in resident education.

Conclusion:

Wellness education and a culture of training that promotes well-being will benefit EM residents. Demonstrating the impact of several factors that positively affect emergency physicians may help to facilitate alert residents to the importance of practicing activities that will result in wellness. A change in culture and focus on resiliency is needed to adequately address and optimize physician self-care.

Keywords: Education, emergency medicine, resident, wellness

INTRODUCTION

Statistics show that 7 to 10% of physicians are disabled by depression, suicide, alcoholism, drug abuse, or unhappy marriages.[1] Emergency medicine (EM) residents have been found to have a higher prevalence of substance abuse compared to other specialties.[2] Despite these sobering statistics, it is a challenge to emphasize and legitimize wellness in resident education. We believe a culture change must occur in medicine to address physician self-care, focus on resiliency, and adopt a preventative and pro-active approach.

The concept of wellness and well-being is a growing area of focus and interest among healthcare professionals. Burnout has received considerably more attention in the literature and is defined as a combination of three elements: (1) emotional exhaus-tion: the depletion of emotional energy by continued work-related demands, (2) depersonalization: a sense of emotional distance from one's patients or job, and (3) low personal accomplishment: a decreased sense of self worth or efficacy related to work.[3] Burnout is the unintended endpoint when wellness and well-being are not achieved and maintained in health care professionals. While burnout is associated with low job satisfaction and may lead to medical errors among physicians, little is known on the types of intervention that may mitigate against burnout.[4,5]

One example of culture change is the establishment of a wellness and well-being committee and creation of a curriculum on wellness and physician self-care for resident physicians. With the introduction of wellness topics early in residency, the ultimate goal is to increase resiliency and decrease burnout. The benefits of cultural change include providing positive educational environment for physicians, raising awareness of burnout and its symptoms, decreasing the stigma associated with admitting burnout symptoms, enabling the development of prevention strategies, and creating a more positive, strength-based approach to understanding the toll of physician-patient relationships on physicians.[6]

Training programs that maximize the health and well-being of their residents have the greatest chance of producing successful and competent graduates with greater odds of long-term career and life satisfaction. Physical health, the absence of substance dependence or mental illness, strong social and family connectedness, and effective use of stress management tools together provide a structure for the vitality and resilience necessary to meet and overcome the challenges and stresses inherent in a life in emergency medicine. There is no standardized wellness curriculum in use by EM residencies in spite of increasing evidence over the last 15 years of significant health and well-being risks to our residents both during training and beyond. A compelling argument can be made for why a comprehensive wellness curriculum is not only legitimate, but also essential.

Much of the current dialogue surrounding resident wellness has shifted in the last 5 years among all specialties and at the level of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). In the past, the literature and the medical community focused primarily on end stage manifestations of neglected health among trainees: burnout, career dissatisfaction, attrition, and impairment due to mental illness, depression, suicide, or substance abuse. The model has shifted and now it is simply not enough to address these end stage problems. A proactive and preventive approach is called for. Residency programs need to anticipate the effect of known stressors and challenges and implement effective preventive strategies to help residents thrive during training and to give them the skills and education necessary to meet the predictable challenges to come after graduation. This shift in focus parallels the overall shift in medicine from the focus on the disease process to preventive care.

DISCUSSION

Raising awareness

A paradigm shift is needed to convince residents and educators that wellness is more than just “fluff” and plays an important role in their education and future career. An initial step towards legitimizing wellness maybe education on the impact of several important negative factors on EM physicians including substance abuse, circadian disruption, sleep deprivation, malpractice and fear of litigation, exposure to infectious disease, maintaining nutrition and exercise, and exposure to patient mortality.

Substance abuse

Studies suggest that substance use and alcoholism among EM physicians parallels the general population with rates from 8-15%.[7] However, it is thought that substance use and abuse by physicians is underreported. In one study, EM physicians were found to have rates three times greater than physicians from other specialties.[2] This increase is thought to be due to baseline characteristics of the group and to the high stress burden of working in the emergency department (ED). Most studies show that alcohol is the most common substance used. A recent study reported that 7.6% of EM residents answered at least one of the CAGE alcohol dependence questions positively and also reflected an increase in daily drinking.[8] Several studies suggest that the roots of substance use problems begin during training. The literature also suggests that early discovery and treatment of substance abuse offers a greater chance for full recovery for the health care professional.[9]

Strategies to address substance abuse problems include encouraging confidential self reporting, increasing access to treatment programs and local resources, and allowing protected feedback from co-workers to help identify problems early on. Residents have scheduled reviews with their program directors and mentors; health, overall wellness, and specific discussion of substance abuse should be topics of regular review. Educational programs are needed to review potential warning signs of substance abuse and departments should be encouraged to work as a team and monitor signs of impairment amongst each other. Residents and faculty should be encouraged to discuss their concerns about co-workers that may be further investigated by departmental leadership. Some programs may assign a specific role of Wellness Director at their institution or department to serve as an additional resource. The Wellness Director should not be involved in performance evaluation or peer review, but rather serve as an independent protected source of information, counseling, and support. Other opportunities to explore what impacts physician wellness may involve a on-going discussion time during a resident retreat or meeting. In these settings, residents may feel more comfortable discussing personal struggles amongst their peers without scrutiny or judgment by faculty. This proactive and preemptive approach may help identify issues early before major problems develop.

Circadian disruption

Circadian disruption (CD) is important to emergency physicians because of its ill effects on well-being: specifically, sleep pattern disruption, health, and psychological mood. For most people, working overnight shifts and alternating day and night shifts results in CD. This disruption has a negative physiologic impact on most every body systems with both short and long-term consequences. Short-term consequences include sleep disturbances (the most frequent side effect) resulting in increased sleepiness when awake and insomnia.[10,11] Decreased alertness and performance, a sense of “not feeling well”,[12] gastrointestinal disturbances,[13] and fertility issues,[14,15] can also occur. Long-term effects include increased rates of hypertension, chronic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and some forms of cancer.[10,16] There are things that can be done to assist in coping with short-term effects of CD but there are no known methods to prevent long-term side effects.

Emphasis on maintaining a healthy body, exercising regularly, rotating shift schedules in a clockwise direction, scheduling consecutive night shifts, maintaining close family and social ties, and continuing to have a positive attitude toward the practice of emergency medicine have been suggested as methods of coping with the distress caused by rotating shifts and working night shifts.[17,18]

Sleep deprivation

Studies have shown that otherwise healthy residents often have levels of sleepiness equal to those with obstructive sleep apnea or other sleep disorders.[19] Even at low levels of sleep deprivation, peak performance is difficult, often leading to mistakes, interpersonal conflicts, and medical errors.[19,20] One study found that <5 hours of sleep per night leads to increased chance of being named in a malpractice suit.[21] Outside the hospital, this can cause major motor vehicle accidents, familial conflict, burnout, and depression.[19,21]

Residents often unsuccessfully attempt to manage their sleep deprivation. Caffeine is the most common pharmacological strategy employed, although some physicians will use ephedrine or even prescription drugs.[22] Any stimulant abuse runs the risk of withdrawal symptoms once it is no longer used. Other healthier strategies include dietary changes, front-loading sleep, napping, and regular exercise, but can be difficult with a busy training schedule.[22] Another strategy for improved sleep is finding a dedicated sleep room that is devoid of light, noise, and distraction. This may help aid in daytime sleep and increase periods of uninterrupted rest.

Finally, one should consider how to balance night shifts with age and other life responsibilities. Parents of school age children may opt to work more nights and sleep during the day while the children are in school to maximize time with their family and achieve a more consistent schedule. As night shifts become more difficult with age, physicians may consider alternatives as their careers mature. Some may opt to pay other co-workers to pick up or trade undesirable shifts, accept a lower salary to work day shifts, change working environment to urgent care, cruise ship medicine, or other careers within emergency medicine that offers better hours and sustainable longevity.

Malpractice and fear of litigation

Medical malpractice has unfortunately become a part of everyday life for practicing physicians. In 2009, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the direct cost providers would incur for medical malpractice liability would total approximately $35 billion.[23] The chances of being sued as a physician are high, regardless of specialty field.[24] EM has historically been viewed as a higher risk malpractice specialty in part due to patient acuity, lack of control over patient volume, and limited interaction time with patients and families in a non-established patient-physician relationship.

The threat of litigation affects our well-being to the point it changes our clinical practice. Concerns of litigation can affect diagnostic tests ordered, the style of chart completion, or ultimate patient disposition decisions.[25,26] A mail survey of high-risk litigation specialties which included EM revealed 93% of physicians practiced defensive medicine.[27] Issues of malpractice can affect where we live. Tort reform within a state has been associated with increase physician supply to the area.[28] Many physicians are ashamed of being sued and become isolated from family and friends as attempt to deal with the stress in secret. Most distressing of all, the forever looming threat of litigation can affect career longevity.[29]

The resident physician's concerns of malpractice and fear of litigation are valid and the threat is real. The key to wellness is to acknowledge this risk, be savvy on steps to reduce the risk, all while maintaining balance of realistic and safe patient care standards that are ethically correct and in the patient's best interest. Strategies for risk management, improved documentation, and introduction to the litigation process should be incorporated into resident education. Education demystifies the legal process and empowers physicians to prepare for depositions, know what resources are available to them, and may decrease the emotional distress associated with malpractice cases. Although fear is a motivating factor for learners, there are other non-threatening resources readily available for resident education. Emergency medicine specific education includes a webinar series, “You’ve been Sued, Now What?” on the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Website, an audio series entitled Risk Management Monthly, and book series, Bouncebacks, which discussed actual EM cases and litigation. Additionally, most hospital risk management departments offer videos and other educational tools. Finally, open communication with family members or friends about being named in a suit is vital. Although one cannot discuss details of a case, a physician is encouraged to discuss the emotional process and seek comfort, support, and validation from a spouse, family, or friend.

Exposure to infectious disease

EM physicians provide care to patients with life-threatening communicable diseases and there is a small but real risk of contracting an infectious disease from the population we serve.[30,31] Even the thought of this potential risk to oneself and one's family is enough to have an effect on the well-being of the EM resident physician.

ED staff are frequently exposed to blood and body fluids which can be the sources of infectious disease.[32] Fifty-six percent of EM residents reported at least one exposure to blood during their training.[33] Further complicating the problem is low rate of reporting, which may compromise appropriate post exposure counseling and prophylaxis.[33] Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are the most common causes of blood-borne health care worker exposure. The only one that can be prevented is hepatitis B. Other non-blood borne infections that can be transmitted to the health care provider also exist in a range of severities, from meningitis to mundane colds.

Certainly prevention is the key and physicians should exercise safety measures and use universal precautions to prevent exposure to blood and other body fluids. Ensuring adequate space, equipment, and preparation for each procedure will decrease the risk of accidental exposure. Maintaining a consistent approach to preparation, set up, and careful disposal of all sharps and equipment will optimize safety. Use of a procedural checklist may help decrease errors and taking a brief time out before each procedure may allow an additional opportunity for safety for both patient and physician.

Maintaining exercise and nutrition

Exercise and nutrition play key roles in avoiding obesity and contributing to wellness. Unfortunately, they are frequently neglected during medical training and practice due to increased time at work, decreased time for exercise, lack of control over food choices and eating times, and disrupted sleep patterns. Poor nutrition and lack of exercise can lead to mood swings, poor productivity, and an array of lifelong health problems and concerns.[34]

Physician's health habits have a larger impact than on their own health. It has been shown that physicians who share healthy nutrition and exercise behaviors with patients are found to be more credible and motivating.[35] Furthermore, physicians with healthy habits are more likely to discuss similar preventative habits with their patients.[36] A physician with a healthy lifestyle is one of the most powerful predictors of preventative counseling for patients.[37]

Strategies to improve nutrition include prioritizing small breaks for hydration and eating during a shift. Frequent small nutritious snacks in between patient encounters prevent excessive caloric intake after a shift. Engaging in a new physical activity, changing the routine, and joining a group activity can keep exercise fun and increase energy levels.

Patient mortality

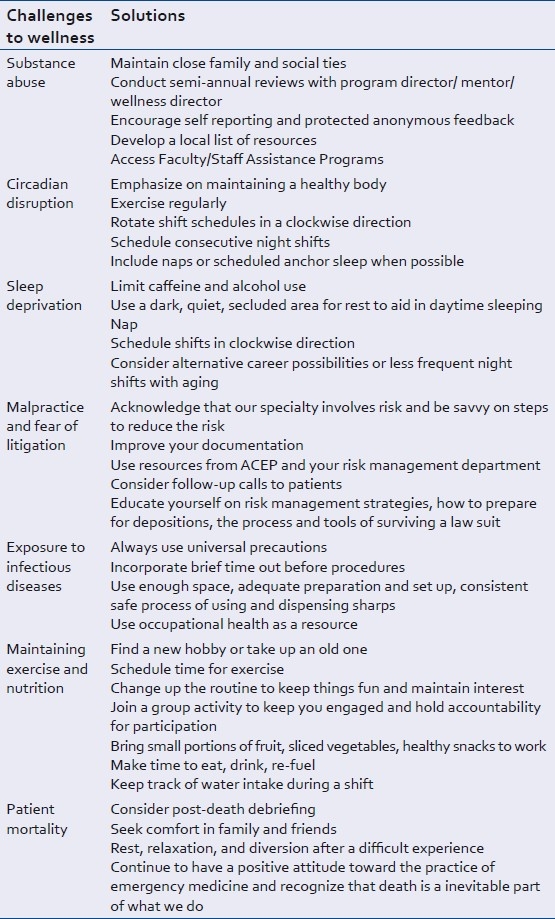

The death of a patient is commonly faced by every practicing emergency physician.[38] Despite our best efforts to the contrary, some of our patients will die under our care. We are often forced into the position of breaking bad news to loved ones while concurrently coping with our own emotions. A busy ED demands that we fill these roles, often with little formal training, then quickly move on to the next patient.[38] Once the physician's role in the patient and family's care is complete, he or she must confront their own personal feelings about the event.[39] Emotions range from depression, guilt, failure, and unworthiness.[38,39] Physical symptoms can also manifest.[38,40] It is not uncommon for those who cared for a dying patient to experience a similar grief as the family.[40] There are many coping mechanisms available. One of the best is a post-death debriefing, allowing the physician to verbalize the experience and move on.[38] It also allows the care team to discuss what could have been done better and to recognize that others feel the same way. Physicians should also seek comfort in family, friends, rest, relaxation, and diversion after a particularly difficult experience [Table 1].[38]

Table 1.

Summary of specific challenges and solutions to wellness in emergency medicine

The need for a strategy

The development of a strategy for wellness begins with the understanding that personal well-being is vulnerable, given the stresses and challenges of residency and subsequently of EM practice. This can lead to more serious consequences than periods of fatigue and unhappiness. Work dysphoria is a spectrum of negative reactions to work that ends in burnout and depression. Its consequences can include poor work performance, increased risk of substance abuse, poor patient outcomes and, at the extremes, abandoning the specialty or clinical depression. The first step in the development of a strategy is to embrace the idea that one is needed.

The next requirement is to abandon the idea that physician training is an exercise in endurance and bravado. Surely, courage and stamina will be needed, but not the misguided preconception of invulnerability that was pervasive in previous generations. The laws governing resident education and duty hour restrictions reflect a new understanding. Exhausted, discouraged, ill, or injured doctors who depersonalize and resent their patients do not deliver safe, high quality health care. A strategy for well-being will include three distinct types of coping mechanisms: physical health and safety, emotional and psychological coping methods, and one or more stress relief techniques.

Studies strongly suggest that, in general, physicians ignore their personal health. Preventive care as a rule is low or non-existent. Attention to regular exercise, rest and nutrition is rare. In fact it is documented that most physicians work even when they are sick and expect their colleagues to do the same. These practices often begin in training. EM residents find very few positive role models in this regard and are often pressured to ignore issues related to personal health.

The ABEM longitudinal study, one of the only studies of its kind, prospectively followed a cohort of 1000 practicing EM physicians from 1994-2005.[41] The data gained from this study offers valuable insights about the predictors of career satisfaction and success in EM. The study reports that 31% of responders indicated that burnout was, and is, still a significant problem in emergency medicine. The ABEM study concludes that effective work-life balance and “making time for personal life and adequate rest and fitness are vital to career satisfaction and avoiding burnout.” It is essential that residency programs educate their trainees about factors known to be associated with greater career satisfaction, longevity, and productiveness and provide them with as many tools as possible to avoid burnout.

CONCLUSION

Wellness education and a culture of training that promotes well-being will benefit residents. The relationship between factors such as fatigue, burnout, poor health, emotional exhaustion, lack of meaning, poor social support, and poor camaraderie with critical outcomes such as clinical performance, ability to learn, empathy for patients, and avoidance of medical errors is intuitively obvious. What we are beginning to learn now, however, is that greater attention to one's personal wellbeing may in fact be associated with better patient care. There is growing evidence in the literature of significant link between improved physician wellbeing with decreased medical errors, decreased burnout and improved empathy as measured with validated metrics.[42] Some authors specifically advocate the regular measurement of physician well-being as an essential marker when measuring the health of health care systems.[43] A change in culture and focus on resiliency, rather than burnout, in wellness education is needed to adequately address and optimize physician self-care. This culture change could impact physician satisfaction working in the ED and create a life-long approach to maintaining joy and interest as an EM physician.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nelson SB. Some dynamics of medical marriages. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1978;28:585–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes PH, Baldwin DC, Sheehan DV, Conard S, Storr CL. Resident physician substance abuse by specialty. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;129:1348–54. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.10.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251:995–1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Kolars JC, Habermann JM, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy. JAMA. 2006;296:1071–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, Hunt R, Balasubramaniam M, Mulhem E, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84:269–77. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181938a45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watkins D. Substance abuse and the impaired provider. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2010;30:26–8. doi: 10.1002/jhrm.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBeth BD, Ankel FK, Ling LJ, Asplin BR, Mason EJ, Flottemesch TJ, et al. Substance use in emergency medicine training programs. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohigian GM, Croughan JL, Sanders K, Evans ML, Bondurant R, Platt C. Substance abuse and dependence in physicians. South Med J. 1996;89:1078–80. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199611000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutenfranz J, Knauth P, Colquhoun WP. Hours of work and shiftwork. Ergonomics. 1976;19:331–40. doi: 10.1080/00140137608931549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith-Coggins , R Rosekind MR, Hurd S, Buccino KR.Relationship of day versus night sleep to physician performance and mood. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:928–34. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruger M, Scheer FA. Effects of circadian disruption on the cardiometabolic system. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2009;10:245–60. doi: 10.1007/s11154-009-9122-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vener KJ, Szabo S, Moore JG. The effect of shift work on gastrointestinal (GI) function: A review. Chronobiologia. 1989;16:421–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Infante-Rivard C, David M, Gauthier R, Rivard GE. Pregnancy loss and work schedule during pregnancy. Epidemiology. 1993;4:73–5. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199301000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mamelle N, Laumon B, Lazar P. Prematurity and occupational activity during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119:309–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erren TC, Reiter RJ. Defining chronodisruption. J Pineal Res. 2009;46:245–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitehead , DC , Thomas HC, Slapper DC. A rational approach to shift work in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1250–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81758-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houry D, Shockley L, Markovchick V. Wellness issues and the emergency medicine resident. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:394–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papp K, Stoller EP, Sage P, Aikens JE, Owens J, Avidan A, et al. The effects of sleep loss and fatigue on resident-physicians: A multi-institutional mixed-method study. Acad Med. 2004;79:394–406. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200405000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, Kaushal R, Burdick E, Katz JT, et al. Effect of reducing interns’ work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1838–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldwin DC, Daugherty SR. Sleep deprivation and fatigue in residency training: Results of a national survey of first- and second-year residents. Sleep. 2004;27:217–23. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoller E, Papp KK, Aikens J, Erokwu B, Strohl K. Strategies resident-physicians use to manage sleep loss and fatigue. [Last cited on 2011 Nov 11];Med Educ Online [Internet] 2005 10(9) doi: 10.3402/meo.v10i.4376. Available from: http://www.med-edonline.net/index.php/meo/article/view/4376/4558. [about 1p.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elmendorf DW. Washington DC: Congressional Budget Office, US Congress); 2009. Oct, (Congressional Budget Office). Background paper. (Congressional Budget Office). 2006. Medical Malpractice Tort Limits and Health Care Spending. CBO Background Paper. April. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodge A, Fitzer S. Dodge Publications; 2001. When good doctors get sued: A guide for defendant physicians involved in malpractice suit. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz DA, Williams GC, Brown RL, Aufderheide TP, Bogner M, Rahko PS, et al. Emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice in evaluating patients with possible acute cardiac ischemia. Ann of Emerg Med. 2005;46:525–33. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong AC, Kowalenko T, Roahen-Harrison S, Smith B, Maio RF, Stanley RM. A survey of emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice and its association with the decision to order computed tomography scans for children with minor head trauma. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:182–5. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31820d64f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudson MJ, Moore GP. Defenses to malpractice: What every emergency physician should know. J Emerg Med. 2011;41:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler DP, Sage WM, Becker DJ. Impact of malpractice reforms on the supply of physician services. JAMA. 2005;293:2618–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doan-Wiggins L, Zun L, Cooper MA, Meyers DL, Chem EH. Practice satisfaction, occupational stress, and attrition of emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:556–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Washington, DC: US Department of Labor, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1987. Department of Labor, Department of Health and Human Services. Joint advisory notice: protection against occupational exposure to hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Update: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and human immunodeficiency virus infection among health-care workers. MMWR. (239).MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:229–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jagger J, Powers RD, Day JS, Detmer DE, Blackwell B, Pearson RD. Epidemiology and prevention of blood and body fluid exposures among emergency department staff. J Emerg Med. 1994;12:753–65. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(94)90480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee CH, Carter WA, Chiang WK, Williams CM, Asimos AW, Goldfrank LR. Occupational exposures to blood among emergency medicine residents. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1036–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fletcher GF, Balady G, Blair SN, Blumenthal J, Casperson C, Chaitman B, et al. Statement on exercise: Benefits and recommendations for physical activity programs for all Americans.A statement for health professionals by the committee on exercise and cardiac rehabilitation of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996;94:857–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.4.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank E, Breyan J, Elon L. Physician disclosure of healthy personal behaviors improves credibility and ability to motivate. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:287–90. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis CE, Clancy C, Leake B, Schwartz JS. The counseling practices of internists. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:46–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-1-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frank E, Rothenberg R, Lewis C, Belodoff BF. Correlates of physicians’ prevention-related practices. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:359. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strote J, Schroeder E, Lemos J, Paganelli R, Solberg J, Range-Hudson H. Academic emergency physicians’ experiences with patient death. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:255–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knazik SR, Gauche-Hill M, Dietrich AM, Gold C, Johnson RW, Mace SE, et al. The death of a child in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:519–29. doi: 10.1067/s0196-0644(03)00424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruce CA. The grief process for the patient, family, and physician. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2002;102(9 Suppl 3):S28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cydulka RK, Korte R. Career satisfaction in emergency medicine: The ABEM longitudinal study of emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;51:714–22. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.01.005. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Croskerry P, Wears RL, Binder LS. Setting the educational agenda and curriculum for error prevention in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1194–2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: A missing quality indictor. Lancet. 2009;374:1714–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]