Abstract

Intestinal obstruction (IO) is a common cause of acute abdominal pain. The recent increased use of sonography in the initial evaluation of abdominal pain has made point-of-care ultrasound a valuable tool for the diagnosis of IO. Sonography is as sensitive, but more specific, than plain abdominal X-ray in the diagnosis of IO. Point-of-care ultrasound can answer specific questions related to IO that assist the acute care physician in critical decision making. Sonography can also help in the resuscitation of patients by serial measurement of the IVC diameter. We review the sonographic findings of IO and the role of point-of-care ultrasound in the management of patients having IO.

Keywords: Diagnosis, intestinal obstruction, ultrasonography

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal obstruction (IO) is a common cause of acute abdominal pain. Effective treatment depends on rapid and accurate diagnosis especially for patients who need early operative intervention.[1]

Diagnosis of bowel obstruction is usually made on the basis of the clinical picture confirmed by plain radiography of the abdomen as the initial investigation.[2] The plain abdominal X-ray findings of IO of dilated bowel loops and multiple air-fluid levels may not be obvious especially in proximal gastrointestinal tract obstruction.[3] Contrast studies on the other hand are time-consuming, poorly tolerated, and subject patients to radiation especially in pregnant women.[3] The increased use of sonography in the initial assessment of patients with abdominal pain has made point-of-care ultrasound a valuable tool for the diagnosis of IO. Sonography is as sensitive but more specific than abdominal X-ray in the diagnosis of IO.[4,5] Furthermore, it may detect the cause of obstruction and its level.[2] Repeated scanning is safe and can be used to determine the progress of IO. Point-of-care ultrasound may detect bowel wall necrosis and evaluate the physiological status that can guide the resuscitation of patients with IO.[6] We review the sonographic findings of IO and the role of using point-of-care ultrasound in the management these patients.

Technique and sonography of the normal bowel

It is recommended to start abdominal sonography with a 3.5-5 MHz sector transducer so to have a general overview of the abdomen. For more detailed information, higher frequency transducers (7.5-14 MHz) are used. Color and power Doppler gives information about the blood flow within the wall of the intestine.[7,8] The patient should be examined in the supine position without special preparation. Scanning of the colon can be performed through its course along the flanks and in the upper abdomen along the midline; for sigmoid colon along the left lower abdomen toward the pelvic cavity; and for the rectum along the midline of the pelvic cavity. Small bowel loops can be scanned in the central region of the abdomen. Bowel loops may contain gas or fluid. These can be displaced by gentle pressure through moving the transducer slowly over the abdomen (graded compression) to squeeze the air away from the region of interest so as to detect any pathology.[8]

Normally, the bowel appears as a single circular hypoechoic layer (muscle layer) surrounding hyperechoic bowel contents of gas and food particles. The normal thickness of this layer during the contraction stage of peristalsis is 2-3 mm. The hypoechoic normal wall becomes thinner during peristalsis when the bowel is relaxed.[8]

Sonographic findings of IO

Point-of-care ultrasound helps the acute care physician to answer the following questions:

1) Is the bowel obstructed? 2) What is the type of obstruction (mechanical or functional)? 3) Where is the site of obstruction? 4) What is the cause of the obstruction? 5) Is the bowel necrotic and does the patient need emergency surgery? 6) What is the clinical progress in patients treated conservatively?

The sonographic findings of an obstructed bowel include dilated fluid- filled bowel loops with hyperechoic spots of gas moving within the fluid. The normal small intestine diameter is 3-4 cm while the diameter of the large intestine 4-5 cm.[2,5] Those dilated loops may show thickened wall (normally up to 3 mm),[8] thickened vavulae conniventes (normally up to 2 mm), and increased to-and-fro motion of the bowel contents [Figure 1].[2]

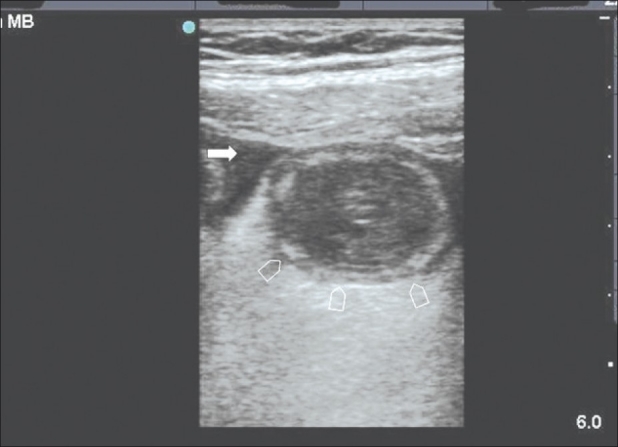

Figure 1.

Sonographic section of the central abdomen using a linear probe showing a dilated small bowel (arrow heads) with thickened mucosa and free intraperitoneal fluid (arrow). At laparotomy a segment of the small bowel was gangrenous

Real-time sonography may differentiate between mechanical and functional IO. The movement of the mechanically obstructed bowel will initially increase but will decrease later with the progress of the obstruction and development of bowel ischemia.[6] Akinesis of the loop can be detected by absence of bowel peristalsis for more than 5 minutes.[5] The site of IO is determined by following the course of obstructed bowel by ultrasound probe and by the pattern of valvulae conniventes.[2]

The transit point is the point between the dilated proximal and collapsed distal bowel loops.[2] It is important to search for the cause of IO at the transit point. Ultrasound may detect the cause of IO with specific sonographic findings such as: External hernias, intestinal intussusception, tumors, ascariasis, superior mesenteric artery syndrome, bezoars, foreign bodies and Crohn's disease.[2,7–10]

A decision for early surgery is one of the most important decisions that point-of-care ultrasound can assist the surgeon with. Sonographic findings suggesting a need for surgery include; intraperitoneal free fluid [Figures 2a–c], bowel wall thickness of more than 4 mm, and decreased or absent peristalsis in previously documented mechanically obstructed bowel.[5,6,11] Bowel wall perfusion can be assessed by Doppler sonography[1] and the presence of free intraperitoneal air indicates bowel perforation. Under ultrasound guidance, aspiration of bloody intraperitoneal fluid may indicate bowel gangrene that needs urgent surgery.[12] In critically ill patients having IO and a hypovolemic shock, ultrasound can help in the diagnosis and resuscitation of these patients by serial measurement of the IVC diameter [Figure 3 a–b].[13]

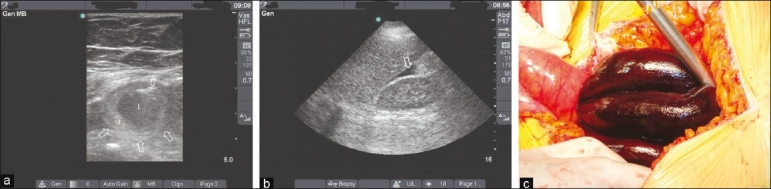

Figure 2.

A 60-year-old woman presents with a clinical picture of intestinal obstruction. Sonographic section of the lower abdomen using a linear probe (a) showed a dilated small bowel (arrows) with thickened mucosa (M) and fluid-filled lumen (L). The arrow head shows a hyperdense echogenic line within the bowel wall indicating ischemia of the bowel. Coronal sonographic section of the right hypochondrium using a curvilinear probe (b) showed free intraperitoneal fluid in Morrison's pouch (arrow). (c) Laparotomy has revealed a gangrenous small bowel loop in the pelvis as a result of a single fibrous band

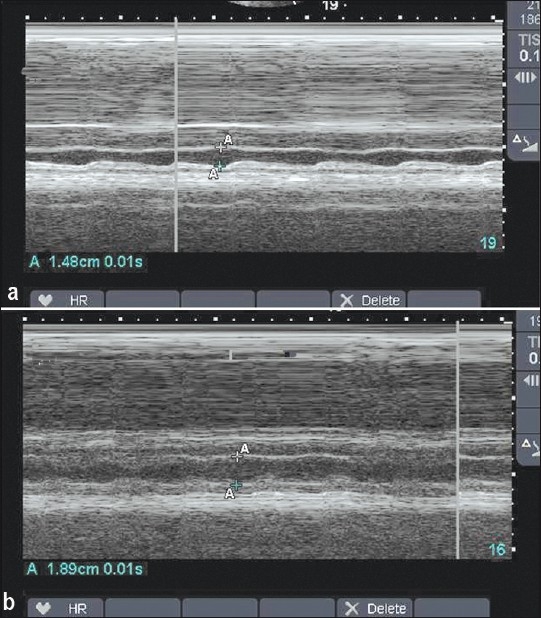

Figure 3.

(a) M-mode of the inferior vena cave before and after (b) resuscitation of the patient shown in Figure 2. Notice the obvious variation in the IVC diameter before resuscitation and the increased diameter of the IVC and less variation in the diameter after resuscitation

Serial ultrasound examinations are safe and can be used to evaluate the progress of IO in patients who are treated conservatively.[5] Furthermore, ultrasonography can be used to guide the hydrostatic reduction of intussusception in children.[7]

CONCLUSIONS

Ultrasound is a valuable tool in the diagnosis of IO. It can differentiate between mechanical and functional IO. Obstructed bowel loops appear sonographically to be dilated, thickened wall and fluid filled with hyperechoic spots (gas). Acute care physicians performing point-of-care ultrasound following up patients with mechanical IO should know the warning signs of possible bowel ischemia. These are: The presence of intraperitoneal free fluid, bowel wall thickness of more than 4 mm, and decreased or no peristalsis of previously hyperactive bowel.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nicolaou S, Kai B, Ho S, Su J, Ahamed K. Imaging of acute small-bowel obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1036–44. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silva AC, Pimenta M, Guimarães LS. Small bowel obstruction: What to look for. Radiographics. 2009;29:423–39. doi: 10.1148/rg.292085514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berlin SC, Goske MJ, Obuchowski N, Alexander F, Zepp RC, Goldblum JR, et al. Small bowel obstruction in rats: Diagnostic accuracy of sonography versus radiography. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:497–504. doi: 10.7863/jum.1998.17.8.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson NG, Heriot AG, Kumar D, Joseph AE. Abdominal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of colonic cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:530–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogata M, Mateer JR, Condon RE. Prospective evaluation of abdominal sonography for the diagnosis of bowel obstruction. Ann Surg. 1996;223:237–41. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199603000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grassi R, Romano S, D’Amario F, Giorgio Rossi A, Romano L, Pinto F, et al. The relevance of free fluid between intestinal loops detected by sonography in the clinical assessment of small bowel obstruction in adults. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nylund K, Ødegaard S, Hausken T, Folvik G, Lied GA, Viola I, et al. Sonography of the small intestine. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1319–30. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim JH. Ultrasound examination of gastrointestinal tract diseases. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15:371–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.4.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu-Zidan FM, Hefny AF, Saadeldinn YA, El-Ashaal YI. Sonographic findings of superior mesenteric artery syndrome causing massive gastric dilatation in a young healthy girl. Singapore Med J. 2010;51:e184–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hefny AF, Saadeldin YA, Abu-Zidan FM. Management algorithm for intestinal obstruction due to ascariasis: A case report and review of the literature. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009;15:301–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maglinte DD, Kelvin FM, Sandrasegaran K, Nakeeb A, Romano S, Lappas JC, et al. Radiology of small bowel obstruction: Contemporary approach and controversies. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:160–78. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheible W, Goldberger LE. Diagnosis of small bowel obstruction: The contribution of diagnostic ultrasound. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133:685–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.133.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanagawa Y, Sakamoto T, Okada Y. Hypovolemic shock evaluated by sonographic measurement of the inferior vena cava during resuscitation in trauma patients. J Trauma. 2007;63:1245–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318068d72b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]