Abstract

Analysis of biochemical systems requires reliable and self-consistent databases of thermodynamic properties for biochemical reactions. Here a database of thermodynamic properties for the reactions of glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle is developed from measured equilibrium data. Species-level free energies of formation are estimated based on comparing thermodynamic model predictions for reaction-level equilibrium constants to previously reported data obtained under different experimental conditions. Matching model predictions to the data involves applying state corrections for ionic strength, pH, and metal ion binding for each input experimental biochemical measurement. By archiving all of the raw data, documenting all model assumptions and calculations, and making the computer package and data available, this work provides a framework for extension and refinement by adding to the underlying raw experimental data in the database and/or refining the underlying model assumptions. Thus the resulting database is a refinement of preexisting databases of thermodynamics in terms of reliability, self-consistency, transparency, and extensibility.

Keywords: biochemical thermodynamics, network thermodynamics, reaction database, network-level optimization, glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle

Introduction

The principles of biochemical thermodynamics are widely applied in biochemical process design and in theoretical/computational analyses of cellular metabolic networks 1. Thermodynamic data on biochemical reactions may be used to predict the extent of reaction, to optimize product yields, and to calculate the energy requirements of a given reaction 2. Recent theoretical studies have combined mass-balance (flux-balance) and thermodynamic constraints to determine feasible ranges of metabolite concentrations 3,4 and have combined metabolic and thermodynamic data to determine feasibility of pathway fluxes in genome-scale networks 5–8. Furthermore, physically realistic simulation of biochemical system kinetics requires integrating data on thermodynamics and kinetics into a coherent self-consistent set of model equations and associated computer codes 9,10. These and similar applications require estimated values of basic thermodynamic quantities (such as the standard reference changes in enthalpy, entropy, and free energy) associated with biochemical reactions under given conditions.

To date, the field has relied heavily on the work of R. A. Alberty, who has not only made a number of important theoretical contributions, but also developed a database of derived thermodynamic data for biochemical reactions 11. His work provides the most extensive database of thermodynamic properties available (in terms of number of reactions covered), including the reactions of glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), the purine nucleotide cycle, and a number of other pathways 11–20. Our laboratory, for example, has made extensive use of the Alberty database, with minor additions, in much of our work in this area 21–23. Yet optimal progress in the field will require significant extension and refinement because the database does not include all biochemical reactions and associated reactants that are involved in cellular metabolism and other key biochemical processes. Furthermore, enthalpy values, which are essential for accounting for temperature effects, are largely missing from current databases. In addition, it is not clear precisely what raw data were used to obtain the values in the Alberty database. This is a critical issue for several reasons. First, calculation of the formation properties from the raw data requires determination of the solution properties (ionic strength, free metal cation concentrations) associated with the raw experimental data. These determinations often require invoking approximations and making related decisions in a case-specific manner. Second, because the calculated formation properties are interrelated, the database of formation properties may be rigorously extended only by re-calculating the entire database using all of the raw data.

Goldberg and colleagues have compiled an extensive database of biochemical thermodynamic data that provides the opportunity to build a large-scale extensible database of biochemical thermodynamic properties 20,24. Their efforts include carefully evaluating and tabulating thermodynamic data and experimental conditions reported in an enormous number of studies (over 1000 original papers) into a database of thermodynamic measurements on enzyme catalyzed reactions 2,20,25–30 and analyzing subsets of these raw data to estimate the species formation free energies, enthalpies, entropies, and heat capacities 24. (The raw data are apparent equilibrium constants measured under various biochemical conditions; the derived properties are free energies and enthalpies of formation of chemical species at standard reference conditions.)

The goal of the current work is to present a novel database of thermodynamic properties for the reactions of glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle (25 total reactions), based on the raw data compiled by Goldberg and colleagues. Thus, like the Alberty database, this initial effort represents only a fraction of the reactions accounted in the Goldberg dataset. Yet our database represents a refinement to the Alberty database in that it accounts for the ionic strength and interactions of biochemical reactants and metal cations (Mg2+, Ca2+, Na+, and K+) in estimating the derived properties from the raw data. Accounting for this level of detail requires estimating the solutions properties (ionic strength, pH, and concentrations of metal cations) associated with each biochemical measurement used in the raw database. Crucially, to make the database extensible, we make the raw data and our documented estimations of solution properties electronically available. Thus, our model represents a framework which may be extended easily and improved in the future by adding more data and/or improving the model assumptions.

Biochemical Thermodynamics Calculations

Derived thermodynamic properties (standard-state Gibbs free energies of formation, , for reference species and reaction enthalpies, ΔrHo,, for reference reactions) may be used to estimate apparent equilibrium constants for biochemical reactions for comparison to experimental data measured under non-standard conditions. In this work, reference and ΔrHo values are estimated based on minimizing the difference between model predictions and experimental data. This section outlines the basic formulae for converting standard-state reference quantities to account for experimental state, based on a number of simple thermodynamic models accounting for temperature, ionic screening, and ion binding 11,31.

Standard-state properties of chemical reference reaction

The standard state defined as the reference state in this work is temperature T = 298.15 K and ionic strength I = 0. For each biochemical reactant a reference species is defined, which is the minimum-cation-bound state considered for a given reactant (For inorganic phosphate HPO42− is the reference species because our calculations ignore PO43−, a species that is present in significant quantities only at pH values above 12.4.). Consider a chemical reference reaction, which is stoichiometrically balanced 31:

| (1) |

where N is the total number of species and νi is the stoichiometric coefficient associated with the species Ai. (The stoichiometric coefficient is negative for species consumed by the reaction, positive for species generated by the reaction.) The standard reaction Gibbs energy and enthalpy can be calculated as follows:

| (2) |

| (3) |

(Here values of species-level values and reaction level ΔrHo values are estimated because the available data do not allow for estimation of for the species involved in the reaction studied.)

Temperature and ionic interactions

Over the temperature range T = 273.15 K to 313.15 K, the effects of temperature (T) and ionic strength (I) on reference reaction Gibbs free energy and enthalpy can be effectively approximated using formulae derived from the van’t Hoff relationship and the extended Debye-Hückel theory 11,31–34, assuming ΔrHo is constant over this temperature range. I.e., ΔrHo is a function of I only:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

where I is the ionic strength in Molar (M) units, zi is the valence of species i, and B is an empirical constant taken to be 1.6 M−1/2. Here α(T) is the coefficient in the Debye equation ln γ = −αz2I1/2,, where γ is the activity coefficient of a species with valence z; the coefficients of the polynomial expansions α(T) and β(T) are obtained from fitting data 35.

A pK is the negative base-10 logarithm of a dissociation constant Kd; the influence of T and I on a pK value is approximated 9:

| (8) |

where ΔdHkd is the dissociation enthalpy.

Ionic binding

At given T and I, the equilibrium constant, K, for a reference chemical reaction and the apparent equilibrium constant, K’, for the associated biochemical reaction are related 31:

| (9) |

where Pj is the binding polynomial associated with reactant j (see below) and vH is the stoichiometric coefficient associated with H+ in the reference reaction.

The apparent equilibrium constant defines the equilibrium mass-action ratio of biochemical reactants defined in terms of sums of species. For example, for the ATP hydrolysis reaction

the apparent equilibrium constant is the mass-action ratio

where the notation [∑•] indicates summation over all species that make up a given reactant. The binding polynomial for a given reactant depends on the free concentrations of hydrogen and metal cations. With pK’s corrected for given T and I, the binding polynomial for reactant j is defined 36:

| (10) |

Each term in the binding polynomial determines the relative amount of reactant j in an associated bound state. For example the fraction of reactant in the single Mg2+-bound state is .

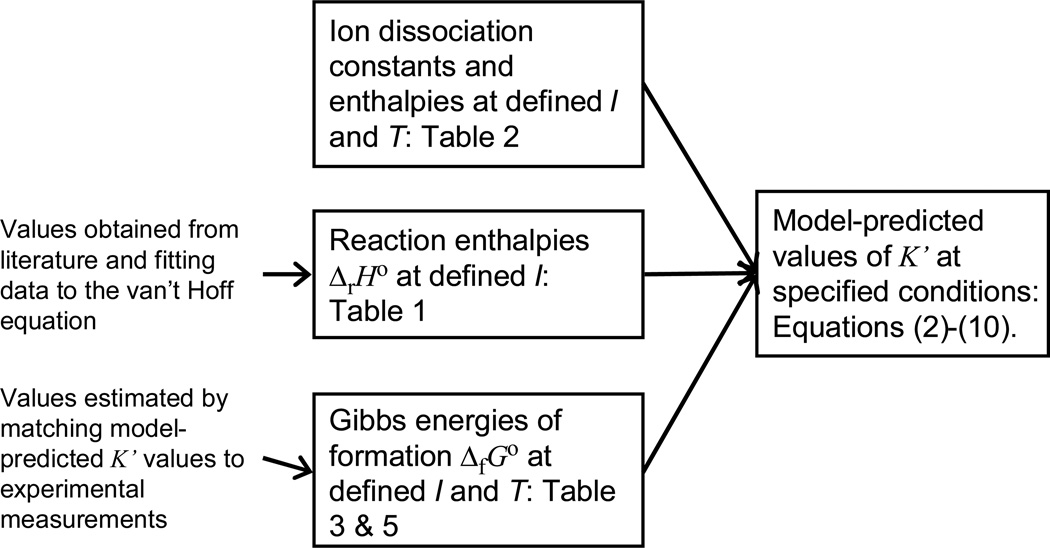

The steps involved in estimating apparent equilibrium constants from species-level thermodynamic properties are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of thermodynamic model calculations.

Input data

Database of measured equilibrium constants

Database development starts with compiling measured equilibrium constants for reactions involving reactants from glycolysis and the TCA cycle. The raw experimental data are largely obtained from original reports included in the Goldberg et al. database 2,25–28. (Data on the ATP hydrolysis reaction are obtained from Rosing et al. 37, a study which is not listed or evaluated in the Goldberg et al. database. Data on the pyruvate kinase reaction are obtained from Dobson et al. 38. All other sources of data are cited and evaluated in the Goldberg et al. database.) Using this collection of papers, we are able to make use of the critical evaluations of Goldberg et al., which include quality ratings assigned according to the details reported in the individual studies 2. Specifically, we preferentially selected data evaluated as “A” quality where available for a given reaction. When A-quality data are not available, we have populated the database with B-quality data. (No data rated “C” or “D” are included in the raw-data database.) Since data on some reactions involved in TCA cycle are not available, data on several additional reactions that operate on glycolysis and TCA cycle reactants are included in the calculations. These additional reactions are NAD(P)+ transhydrogenase (EC 1.6.1.1), malic enzyme (EC 1.1.1.40), malate dehydrogenase 2 (EC 1.1.1.37), NAD+ kinase (EC 2.7.1.23), ATP hydrolysis (EC 3.6.1.32), glucose-6-phosphate hydrolysis (EC 3.1.3.1), and pyruvate carboxylase (EC 6.4.1.1).

Each measurement value compiled in the raw-data database contains the following information: (1.) experimental conditions, including temperature, pH, ionic strength, apparent equilibrium constant, free metal cation concentrations, buffer, and experimental method; (2.) rating and enzyme (EC number); (3.) detailed notes on experiments and strategies of estimations and approximations applied in calculations; and (4.) reference information. This database includes raw data explicitly reported in the original sources and data derived from the conditions reported in the original sources. Estimates of free cation concentrations and ionic strength typically require invoking assumptions, which are explicitly documented in the database. The raw-data database (Biothermo_Rawdata.xls) is available for download as a supplementary file; updated versions of the experimental database will be made available at the URL http://www.biocoda.org.

Approximations and calculations associated with two example reaction entries are detailed in Appendix I. These examples show how the ionic species distribution is computed for the experiments on glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (EC 5.3.1.9) and phosphoglycerate mutase (EC 5.4.2.1), reported by Tewari et al. 39 and Guynn 40, respectively.

Database of reactions and estimated standard reaction enthalpies

The complete set of reactions studied here is defined in Table 1, with EC numbers, reaction names and the abbreviations employed, the reference reaction stoichiometries, and estimated standard reaction enthalpies at T = 298.15 K, I = 0 M. (Recall that a biochemical reactant is made up of a sum of chemical species 11. The reference species for a given reactant is defined here as the minimal-cation-bound state considered in the calculations.) Here we have adopted the convention that chemical species are expressed with a superscript indicating the charge, even when the charge is zero. This way, for example, the abbreviation for references species for glucose (GLC0) is distinguished from the abbreviation for the biochemical reactant GLC. The reactant abbreviations are used as variable names in the computer code and therefore do not use subscripts or superscripts.

Table 1.

Reactions with standard reaction enthalpies ΔrH0 estimated for I = 0.

| EC No. | Reaction Name | Reaction Abbrev. |

Reference Reaction | ΔrH0 (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC 2.7.1.1 | glucokinase | GLK | GLC0 + ATP4− = G6P2− + ADP3− + H+ | −23.8 b |

| EC 5.3.1.9 | phosphoglucose isomerase | PGI | G6P2− = F6P2− | 11.53 a |

| EC 2.7.1.11 | phosphofructokinase | PFK | F6P2− + ATP4− = F16P4− + ADP3− + H+ | −9.5 c |

| EC 4.1.2.13 | fructose-1,6-biphosphatate aldolase | FBA | F16P4− = DHAP2− + GAP2− | 48.97 a |

| EC 5.3.1.1 | triosphosphate isomerase | TPI | GAP2− = DHAP2− | 2.73 e |

| EC 4.1.2.13 | fructose-1,6-biphosphatate aldolase 2 | FBA2 | F16P4− = 2 DHAP2− | 51.70 a |

| EC 1.2.1.12 | glyceraldyde-3-P dehydrogenase | GAP | GAP2− + HPO42− + NAD− = BPG4− + NADH2− + H+ | #d |

| EC 2.7.2.3 | phosphoglycerate kinase | PGK | GAP2− + HPO42− + NAD− + ADP3− = PG33− + NADH2− + ATP4− + H+ | #d |

| EC 5.4.2.1 | phosphoglycerate mutase | PGM | PG23− = PG33− | 28.05 a |

| EC 4.2.1.11 | enolase | ENO | PG23− = PEP3− + H2O0 | 15.1 a |

| EC 2.7.1.40 | pyruvate kinase | PYK | PYR− + ATP4− = PEP3− + ADP3− + H+ | 5.415 b |

| EC 4.1.3.7 | citrate synthase | CITS | OAA2− + ACoA0 + H2O0 = CIT3− + COAS− + 2 H+ | #d |

| EC 4.2.1.3 | aconitrate hydratese | ACON | ISCIT3− = CIT3− | −20.0 a |

| EC 1.1.1.42 | isocitrate dehydrogenase | IDH | ISCIT3− + NADP3− + H2O0 = AKG2− + NADPH4− + CO32− + 2 H+ | −22.17 a |

| EC 6.2.1.4 | succinate-CoA ligase | SCS | GTP4− + SUC2− + COAS− + H+ = GDP3− + HPO42− + SUCCoA− | −30.9 a |

| EC 4.2.1.2 | fumarate hydratase | FUM | FUM2− + H2O0 = MAL2− | −13.18 a |

| EC 1.1.1.37 | malate dehydrogenase | MDH | MAL2− + NAD−1 = OAA2− + NADH−2 + H+ | 51.29 a |

| EC 2.7.4.6 | nucleoside-diphosphate kinase | NDK | ATP4− + GDP3− = ADP3− + GTP4− | #d |

| EC 1.6.1.1 | NADP transhydrogenase | NPTH | NAD− + NADPH4− = NADH−2 + NADP3− | −4.1 c |

| EC 1.1.1.40 | malic enzyme | MLE | MAL2− + NADP3− + H2O0 = PYR− + NADPH4− + CO32− + 2 H+ | #d |

| EC 1.1.1.37 | malate dehydrogenase 2 | MDH2 | MAL2− + ACoA0 + NAD− + H2O0 = CIT3− + COAS− + NADH2− +3 H+ | #d |

| EC 2.7.1.23 | NAD+ kinase | NADK | ATP4− + NAD− = ADP3− + NADP3− + H+ | #d |

| EC 3.6.1.32 | ATPase | ATPS | ATP4− + H2O0 = ADP3− + HPO42− + H+ | −20.5 b |

| EC 3.1.3.1 | Alkaline phosphatase / G6P hydrolysis | G6PH | G6P2− + H2O0 = GLC0 + Pi2− | 0.91 b |

| EC 6.4.1.1 | Pyruvate carboxylase | PCL | PYR− + ATP4− + CO32− = OAA2− + ADP3− + Pi2− | #d |

| EC 1.2.4.1+ EC 2.3.1.12+ EC 1.8.1.4 |

pyruvate dehydrogenase complex | PDH | PYR− + COAS− + NAD− + H2O = CO32− + ACoA0 + NADH2− + H+ | #d |

| EC 1.1.1.41 | isocitrate dehydrogenase | IDH2 | ISCIT3− + NAD− + H2O = AKG2− + NADH2− + CO32− + 2 H+ | −26.27 e |

| EC 1.2.1.52 | α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase | AKGDH | AKG2− + NAD− + COAS− + H2O = SUCCoA− + NADH2− + CO32− + H+ | #d |

| EC 1.3.5.1 | succinate dehydrogenase | SDH | SUC2− + CoQ0 = FUM2− + CoQH20 | # d |

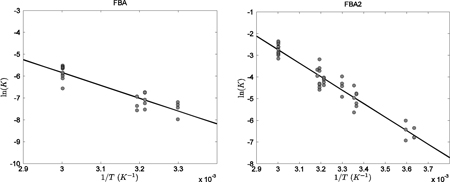

Reaction enthalpies (ΔrH0) reported in Table 1 are obtained as follows: When data on apparent equilibrium constants at different temperatures are available, values for reference reaction equilibrium constant are obtained using Equation (9). These values are adjusted to I = 0 M. Finally, given a set of measures of K at I = 0 and different temperatures, ΔrH0 (I = 0)/R is estimated from the slope of ln(K) vs. 1/T 2. Illustrations of this analysis are given in Appendix II. When the raw-data database provides data at only one temperature for a given reaction, values of ΔrHo are obtained from Goldberg et al. 2,25–28, where available. When neither equilibrium data at different temperatures nor prior values of ΔrHo are available, the symbol ‘#’ is used to denote the absence of data; for these cases the value is set to be zero in further calculations.

The estimates for ΔrHo for certain reactions (FBA, FBA2, and TPI) are based on experimental data obtained at temperatures as high as 333.15 K, which exceeds the valid temperature range of the extended Debye-Hückel theory. Here, the relatively large temperature range facilitates accurate estimates of the slope of ln(K) vs. 1/T yet relies on applying the Debye-Hückel theory outside of the reported range of accuracy. Calculations for ΔrHo for these reactions are detailed in Appendix II.

Database of reactant and dissociation constants

Table 2 lists the basic thermodynamic and ion binding data for biochemical reactants and associated reference species. The format of Table 2 is similar to the reactant database included in the BISEN package recently distributed by our group 41. For each reactant entry the following information is provided: (1.) detailed name of reactant; (2.) reference species abbreviation; (3) reactant abbreviation; (4.) charge of reference species; (5.) number of protons in reference species; and (6.) the dissociation constants (provided as pK) and the corresponding dissociation enthalpies ΔdHKd. Dissociation constants and enthalpies are tabulated at 298.15 K and 0.1 M ionic strength. The symbol ‘#’ is used to indicate absence of data. For these cases, the pK’s are assumed to be infinite (no binding) with corresponding dissociation constants equal to zero. Dissociation enthalpy ΔdHKd is set to be zero in the cases where data are not available.

Table 2.

Reactant database. Dissociation pK and ΔdH are reported for T = 298.15 K and I = 0.1 M. Unless indicated, values are the average number obtained from NIST database 48. Dissociation enthalpies are reported in units of kJ/mol.

| Reactant | Reference species abbrev. |

Reactant abbrev. |

zia | NHa | pKH1 | ΔdHH1 | pKH2 | ΔdHH2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acetyl-coenzyme A | ACoA0 | ACoA | 0 | 3 | # | # | # | # |

| adenosine diphosphate | ADP3− | ADP | −3 | 12 | 6.496 | −2 | 3.87 | 16 |

| adenosine triphosphate | ATP4− | ATP | −4 | 12 | 6.71 | −2 | 3.99 | 15 |

| 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate | BPG4− | BPG | −4 | 4 | 7.1 b | # | # | # |

| citrate | CIT3− | CIT | −3 | 5 | 5.67 | −1.9 | 4.35 | 3.1 |

| coenzyme A-SH | COAS− | COAS | −1 | 0 | 8.17 b | # | # | # |

| carbon dioxide (total) | CO32− | CO2_tot | −2 | 0 | 9.9 b | 16.1 b | 6.15 b | 8.27 b |

| dihydroxyacetone phosphate | DHAP2− | DHAP | −2 | 5 | 5.9 | # | # | # |

| D-fructose 6-phosphate | F6P2− | F6P | −2 | 11 | 5.89 | −0.559 c | 1.1 | # |

| D-fructose 1,6-phosphate | F16P4− | F16P | −4 | 10 | 6.64 | # | 5.92 | # |

| fumarate | FUM2− | FUM | −2 | 2 | 4.09 | −1.56 | 2.86 | 1.08 |

| D-glucose 6-phosphate | G6P2− | G6P | −2 | 11 | 5.89 f | −0.559 c | # | # |

| D-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate | GAP2− | GAP | −2 | 5 | 5.27 b | # | # | # |

| guanosine diphosphate | GDP3− | GDP | −3 | 12 | 6.505 | −2.14 | 2.8 | # |

| D-glucose | GLC0 | GLC | 0 | 12 | # | # | # | # |

| guanosine triphosphate | GTP4− | GTP | −4 | 12 | 6.63 | −3 | 2.93 | 7.1 |

| water | H2O0 | H2O | 0 | 2 | # | # | # | # |

| isocitrate | ISCIT3− | ISCIT | −3 | 5 | 5.765 | # | 4.29 | # |

| α-ketoglutarate | AKG2− | AKG | −2 | 4 | # | # | # | # |

| malate | MAL2− | MAL | −2 | 4 | 4.715 | −0.58 | 3.265 | 3.4 |

| NAD | NAD− | NAD_ox | −1 | 26 | # | # | # | # |

| NADH | NADH2− | NAD_red | −2 | 27 | # | # | # | # |

| NADP | NADP3− | NADP_ox | −3 | 25 | # | # | # | # |

| NADPH | NADPH4− | NADP_red | −4 | 26 | # | # | # | # |

| oxaloacetate | OAA2− | OAA | −2 | 2 | 3.9 | 5.24 | 2.26 | 16.62 |

| orthophosphate | HPO42− | Pi | −2 | 1 | 6.78 | 4.6 | 1.945 | −8.7 |

| 2-phospho-D-glycerate | PG23− | PG2 | −3 | 4 | 7 | # | 3.55 | # |

| 3-phospho-D-glycerate | PG33− | PG3 | −3 | 4 | 6.89 b | # | 3.64 d | # |

| phosphoenolpyruvate | PEP3− | PEP | −3 | 2 | 6.245 | # | 3.45 | # |

| pyruvate | PYR− | PYR | −1 | 3 | 2.26 | 12.8 | # | # |

| succinate | SUC2− | SUC | −2 | 4 | 5.275 | 0.41 | 4.02 | 3 |

| succinyl-CoA | SUCCoA− | SUCCoA | −1 | 4 | 3.99 b | # | # | # |

| ubiquinone (oxidized) | CoQ0 | CoQ | 0 | 90 | # | # | # | # |

| ubiquinone (reduced) | CoQH20 | CoQH2 | 0 | 92 | # | # | # | # |

| Reactant abbrev. | pKMg1 | ΔdHMg1 | pKHMg | ΔdHHMg | pKMg2 | ΔdHMg2 | pKK1 | ΔdHK1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACoA | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| ADP | 3.3 | −15 | 1.59 | −7.5 | 1.27 | −11.76 | 1 | # |

| ATP | 4.28 | −18 | 2.32 | −9.6 | 1.7 | −17.52 | 1.17 | −1 |

| BPG | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| CIT | 3.517 | −8 | 1.8 | # | # | # | 0.6 | −3.54 |

| COAS | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| CO2_tot | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| DHAP | 1.57 | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| F6P | 1.74 f | −9.72 c | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| F16P | 2.7 | # | 2.12 | # | # | # | # | # |

| FUM | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| G6P | 1.74 a | −9.72 c | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| GAP | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| GDP | 3.4 | −7.1 | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| GLC | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| GTP | 4.31 | −17 | 2.31 | # | # | # | # | # |

| H2O | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| ISCIT | 2.625 | # | 1.43 | # | # | # | # | # |

| AKG | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| MAL | 1.71 | −6.16 | 0.9 g | # | # | # | 0.18 | −2.86 |

| NAD_ox | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| NAD_red | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| NADP_ox | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| NADP_red | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| OAA | 1.02 | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| Pi | 1.823 | −9.518 | 0.669 | # | # | # | 0.5 | # |

| PG2 | 2.45 | # | # | # | # | # | 1.18 | # |

| PG3 | 2.21 e | # | # | # | # | # | 0.87 e | # |

| PEP | 2.26 | # | # | # | # | # | 1.08 | # |

| PYR | 1.1 | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| SUC | 1.355 | # | 0.62 | # | # | # | 0.43 | −2.76 |

| SUCCoA | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| CoQ | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| CoQH2 | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| Reactant abbrev. | pKNa1 | ΔdHNa1 | pHHNa | ΔdHHNa | pKCa1 | ΔdHCa1 | pKHCa | ΔdHHCa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACoA | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| ADP | 1.12 | # | # | # | 2.86 | −9.6 | 1.48 | −6.2 |

| ATP | 1.31 | 0.8 | # | # | 3.95 | −13 | 2.16 | −7.9 |

| BPG | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| CIT | 0.75 | −1 | # | # | 3.54 | −1.2 | 2.07 | # |

| COAS | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| CO2_tot | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| DHAP | # | # | # | # | 1.38 | # | # | # |

| F6P | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| F16P | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| FUM | # | # | # | # | 0.6 | −6.44 | # | # |

| G6P | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| GAP | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| GDP | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| GLC | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| GTP | # | # | # | # | 3.7 | # | # | # |

| H2O | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| ISCIT | # | # | # | # | 2.54 | # | # | # |

| AKG | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| MAL | 0.28 | 0.4 | # | # | 1.95 | −1.06 | 1.06 | 8 |

| NAD_ox | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| NAD_red | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| NADP_ox | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| NADP_red | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| OAA | # | # | # | # | 1.6 | # | # | # |

| Pi | 0.61 | # | 0.0856 | # | 1.745 | −9.518 | 0.9212 | −10.759 |

| PG2 | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| PG3 | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| PEP | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| PYR | # | # | # | # | 0.8 | # | # | # |

| SUC | 0.4212 | −2.759 | # | # | 1.405 | −8.939 | 0.65 | −8 |

| SUCCoA | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| CoQ | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

| CoQH2 | # | # | # | # | # | # | # | # |

In Table 2, subscripts on ‘pK’ and ‘ΔdH’ entries are defined as follows: ‘H’: hydrogen, ‘Mg’: magnesium, ‘K’: potassium, ‘Na’: sodium, ‘Ca’: calcium, ‘1’: first ion dissociation, ‘2’: second ion dissociation, ‘HMg’: hydrogen ion binds to the ligand before magnesium ion binds to the ligand Thus the binding polynomial for ATP is computed

pH is defined based on the activity of free hydrogen ion aH+, rather than its concentration [H+]. Thus, pH = −log10(aH+) = −log10 ([H+]· γH+), where γH+ is the activity coefficient for hydrogen ion. In all calculations herein, it is assumed that hydrogen-ion dissociation constants are measured relative to 10−pH, not relative to free hydrogen ion concentration.

The values of in Table 5 are estimated based on the analysis described below.

Table 5.

Optimal predicted for reference species (T = 298.15 K, I = 0 M)

| No. | Species |

(kJ/mol) (this study) |

(kJ/mol) (from Alberty 11) |

Absolute difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GLC0 | −916.39 | −915.90 | 0.49 |

| 2 | ATP4− | −2769.71 | −2768.10 | 1.61 |

| 3 | F6P2− | −1760.81 | −1760.80 | 0.01 |

| 4 | F16P4− | −2597.60 | −2601.40 | 3.80 |

| 5 | DHAP2− | −1292.91 | −1296.26 | 3.35 |

| 6 | GAP2− | −1285.90 | −1288.60 | 2.70 |

| 7 | BPG4− | −2354.55 | −2356.14 | 1.59 |

| 8 | NADH2− | 23.91 | 22.65 | 1.26 |

| 9 | PG33− | −1507.96 | −1502.54 | 5.42 |

| 10 | PG23− | −1502.06 | −1496.38 | 5.68 |

| 11 | PEP3− | −1269.40 | −1263.65 | 5.75 |

| 12 | PYR− | −472.72 | −472.27 | 0.45 |

| 13 | OAA2− | −792.13 | −793.29 | 1.16 |

| 14 | CIT3− | −1157.52 | −1162.69 | 5.17 |

| 15 | ISCIT3− | −1151.76 | −1156.04 | 4.28 |

| 16 | NADP3− | −836.68 | −835.18 | 1.50 |

| 17 | AKG2− | −791.57 | −793.41 | 1.84 |

| 18 | SUC2− | −685.56 | −690.44 | 4.88 |

| 19 | GDP3− | −1904.53 | −1906.13 | 1.60 |

| 20 | FUM2− | −598.74 | −601.87 | 3.13 |

| 21 | MAL2− | −839.30 | −842.66 | 3.36 |

Estimation of Standard-State Thermodynamic Quantities

The thermodynamic model, implemented in MATLAB (Mathworks, Inc), provides a general and extendable framework allowing for easy access and modification. Reference values for the reference species are estimated by minimizing the least-squares difference between model predictions and measured K’ values (weighted in inverse proportion to the number of data points available for a given reaction). For the network of 25 reactions for which data are available (the first 25 reactions listed in Table 1), model fitting is based on a total of 620 data entries. There are 21 stoichiometrically independent reactions in this set of 25 reactions. In other words, the stoichiometric matrix for the 25-reaction set has a rank of 21; values of may be estimated from data on these reactions for 21 references species. Since there are in total 33 reactants in our system, we are unable to independently estimate standard free energies of formation for all the reference species. Thus the values of for 12 species are set to fixed values, as indicated in Table 3. Values for these 12 entries are obtained from Alberty 11. (Values of for CoQ0 and CoQH20 do not come into these calculations.) A weighted simultaneous solution of standard reaction Gibbs energies is obtained for the entire data set by minimizing the difference between model predictions and experimental data. The whole data set is analyzed by a non-linear least squares procedure with the lsqnonlin solver (Mathworks, Inc.).

Table 3.

Values of (T = 298.15 K, I = 0) used in this study and that were taken from Alberty 11 (Table 3.2).

| Species | (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|

| ACoA0 | −188.52 |

| ADP3− | −1906.13 |

| COAS− | 0a |

| CO32− | −527.81 |

| G6P2− | −1763.94 |

| GTP4− | −2768.1 |

| H2O | −237.19 |

| NAD− | 0a |

| NADPH4− | −809.19 |

| HPO42− | −1096.1 |

| SUCCoA− | −509.59 |

| H+ | 0 |

| CoQ0 | 0a |

| CoQH20 | −89.92 |

Property value is based on the arbitrary assignment of zero

Results

Experimental data database

The raw-data database is provided in spreadsheet archived as supplementary material with this paper, and is available for download from http://www.biocoda.org. This database contains raw reported apparent equilibrium constants, along with reported data on experimental conditions and estimates of free ion concentrations obtained from reported experimental conditions. All assumptions invoked in assembling this database are detailed in the spreadsheet database.

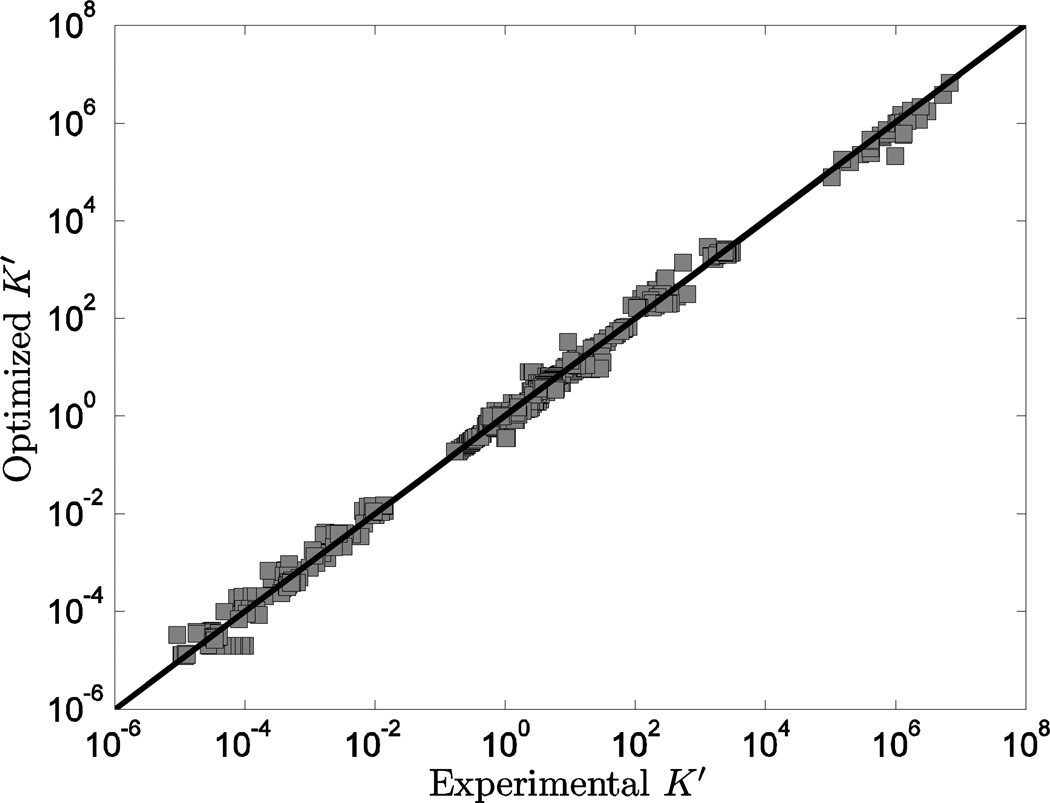

Estimated Gibbs free energies of formation

Computed values of K’ versus experimental measures for all 620 data points are plotted in Figure 2. (Here computed K’ values are obtained based on accounting for the biochemical state associated with a given experimental measurement in the raw-data database.) These data span almost 14 orders of magnitude, and reveal good agreement between model predictions and measured data. The optimal of estimates ΔrGo and that are associated with these predictions are listed in Tables 4 and 5, compared to the values from Alberty 11. Some (3 out of 25) of the current model predictions are indistinguishable from predictions based on the values reported by Alberty, with an absolute difference of less than 0.1 kJ/mol between estimated ΔrGo values. Yet there exist significant differences for several entries, with many differences greater than RT at standard temperature.

Figure 2.

Model-predicted K’ vs. experimental K’. Model predicted apparent equilibrium constants under defined experimental conditions (T, I, [Mg2+], [Ca2+], [Na+], [K+], and pH) are plotted versus experimental measurements for all data in the raw-data database.

Table 4.

Optimal reaction free energies for reference chemical reactions (ΔrGo) and for biochemical reactions (ΔrG'o) under physiological conditions 42,43 (T = 310.15 K, I = 0.18 M, pH = 7, [Mg2+] = 0.8 mM, [K+] = 140 mM, [Na+] = 10 mM, [Ca2+] = 0.0001 mM). The final four entries (PDH, IDH2, AKGDH, and SDH) represent model predictions for which there are no equilibrium data in the raw-data database. Since The values for CoQ and CoQH2 are not predicted here, these values are set to 0a and −89.92 kJ/mol, respectively (from Alberty11) to computed ΔrGo for the SDH reaction.

| EC No. | Reaction | ΔrGo (kJ/mol) (this study) |

ΔrGo (kJ/mol) (from 11) |

Absolute difference |

ΔrG'o (kJ/mol) (physiological conditions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC 2.7.1.1 | GLK | 16.03 | 13.93 | 2.10 | −19.39 |

| EC 5.3.1.9 | PGI | 3.13 | 3.14 | 0.01 | 2.79 |

| EC 2.7.1.11 | PFK | 26.79 | 21.37 | 5.42 | −15.61 |

| EC 4.1.2.13 | FBA | 18.80 | 16.54 | 2.26 | 24.64 |

| EC 5.3.1.1 | TPI | −7.01 | −7.66 | 0.65 | −7.57 |

| EC 4.1.2.13 | FBA2 | 11.79 | 8.88 | 2.91 | 17.07 |

| EC 1.2.1.12 | GAP | 51.37 | 51.21 | 0.16 | 2.60 |

| EC 2.7.2.3 | PGK | 34.37 | 42.84 | 8.47 | −18.99 |

| EC 5.4.2.1 | PGYM | −5.90 | −6.16 | 0.26 | −6.36 |

| EC 4.2.1.11 | ENO | −4.53 | −4.46 | 0.07 | −4.46 |

| EC 2.7.1.40 | PYK | 66.90 | 70.59 | 3.69 | 27.17 |

| EC 4.1.3.7 | CITS | 60.32 | 56.31 | 4.01 | −36.43 |

| EC 4.2.1.3 | ACON | −5.76 | −6.65 | 0.89 | −7.59 |

| EC 1.1.1.42 | IDH | 97.06 | 98.00 | 0.94 | −3.32 |

| EC 6.2.1.4 | SCS | −56.56 | −53.28 | 3.28 | 0.05 |

| EC 4.2.1.2 | FUM | −3.38 | −3.60 | 0.22 | −3.51 |

| EC 1.1.1.37 | MDH | 71.09 | 72.02 | 0.93 | 27.70 |

| EC 2.7.4.6 | NDK | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | −0.57 |

| EC 1.6.1.1 | NPTH | −3.58 | −3.34 | 0.24 | −0.43 |

| EC 1.1.1.40 | MLE | 103.45 | 105.76 | 2.31 | 0.86 |

| EC 1.1.1.37 | MDH2 | 131.41 | 128.33 | 3.08 | −6.67 |

| EC 2.7.1.23 | NADK | 26.90 | 26.79 | 0.11 | −11.93 |

| EC 3.6.1.32 | ATPS | 4.67 | 3.06 | 1.61 | −32.76 |

| EC 3.1.3.1 | G6PH | −11.36 | −10.87 | 0.49 | −13.27 |

| EC 6.4.1.1 | PCL | −24.12 | −27.34 | 3.22 | −4.07 |

| EC 1.2.4.1+ EC 2.3.1.12+ EC 1.8.1.4 |

PDH | 17.50 | 15.78 | 1.72 | −37.49 |

| EC 1.1.1.41 | IDH2 | 93.48 | 94.66 | 1.18 | −4.81 |

| EC 1.2.1.52 | AKGDH | 15.28 | 15.85 | 0.57 | −38.26 |

| EC 1.3.5.1 | SDH | −3.10 | −1.35 | 1.75 | −2.41 |

Property value is based on the arbitrary assignment of zero

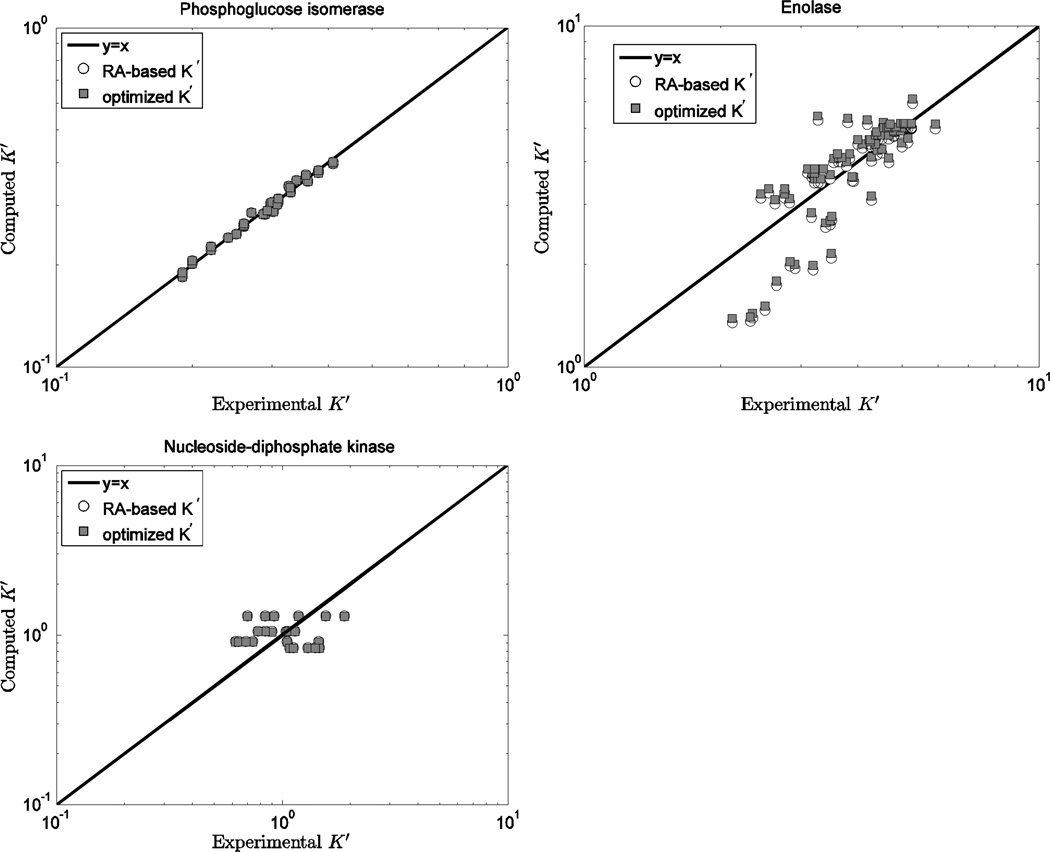

To compare the predictions based on this database to those based on the Alberty database, computed K’ versus experimental measures are plotted in Figures 3, 4, and 5 for 14 individual reactions. Figure 3 illustrates model predictions versus experimental data for the three reactions (PGI, ENO and NDK) for which the current database and the Alberty database yield most similar results. Thus for these reactions, predictions based on either set of values (or equivalently ΔrGo values) are largely indistinguishable. Note that for these three reactions ; thus the ionic interaction terms in Equations (4)–(8) are zero. In addition, the binding polynomials for the left-hand and right-hand sides of these reactions tend to cancel. For example, for the ENO reaction, the ion dissociation constants for PG23− and PEP3− have similar values. Thus the computed apparent equilibrium constants for these reactions do not depend strongly on the experimental ionic composition.

Figure 3.

Computed K’ vs. experimental K’ for the phosphoglucose isomerase, enolase, nucleoside-diphosphate kinase reactions. Open circles (RA-based K’) are computed based on the Alberty database 11; filled squares (optimized K’) are computed based on the optimized values of from Table 5 and the fixed values from Table 3.

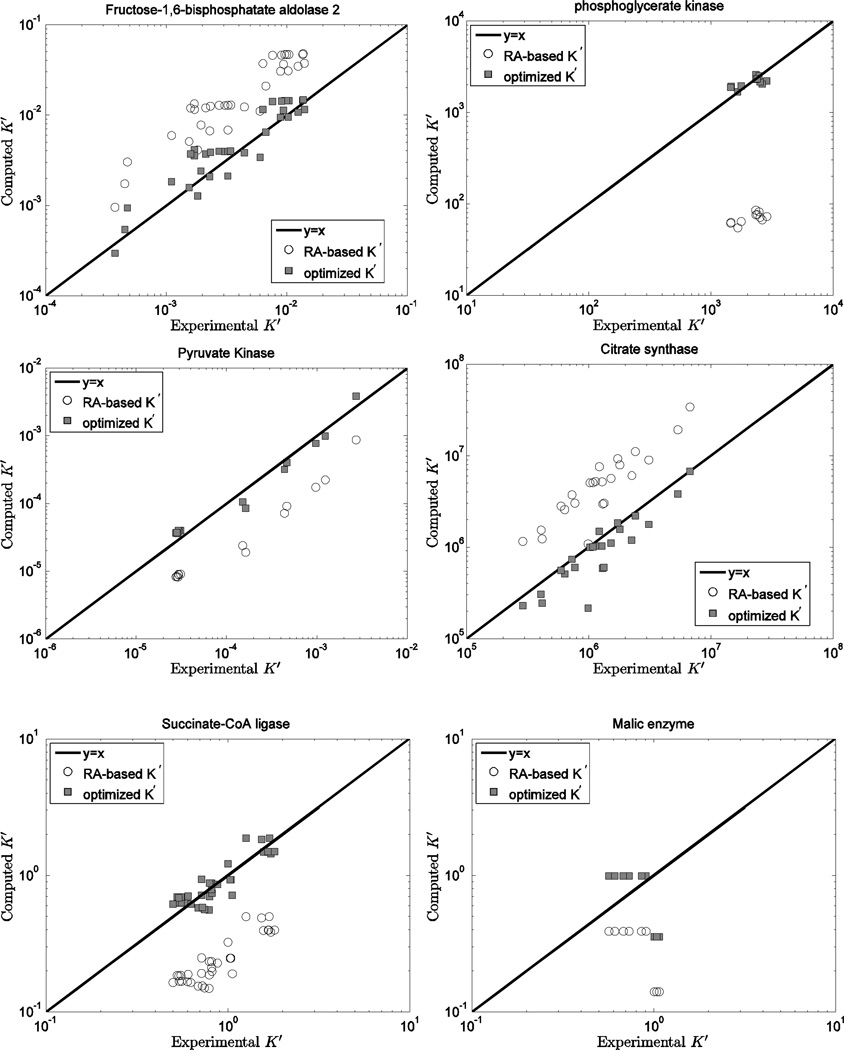

Figure 4.

Computed K’ vs. experimental K’ for the fructose-1,6-biphosphatate aldolase 2, phosphoglycerate kinase, pyruvate kinase, citrate synthase, succinate-CoA ligase, and malic enzyme reactions. Open circles (RA-based K’) are computed based on the Alberty database 11; filled squares (optimized K’) are computed based on the optimized values of from Table 5 and the fixed values from Table 3.

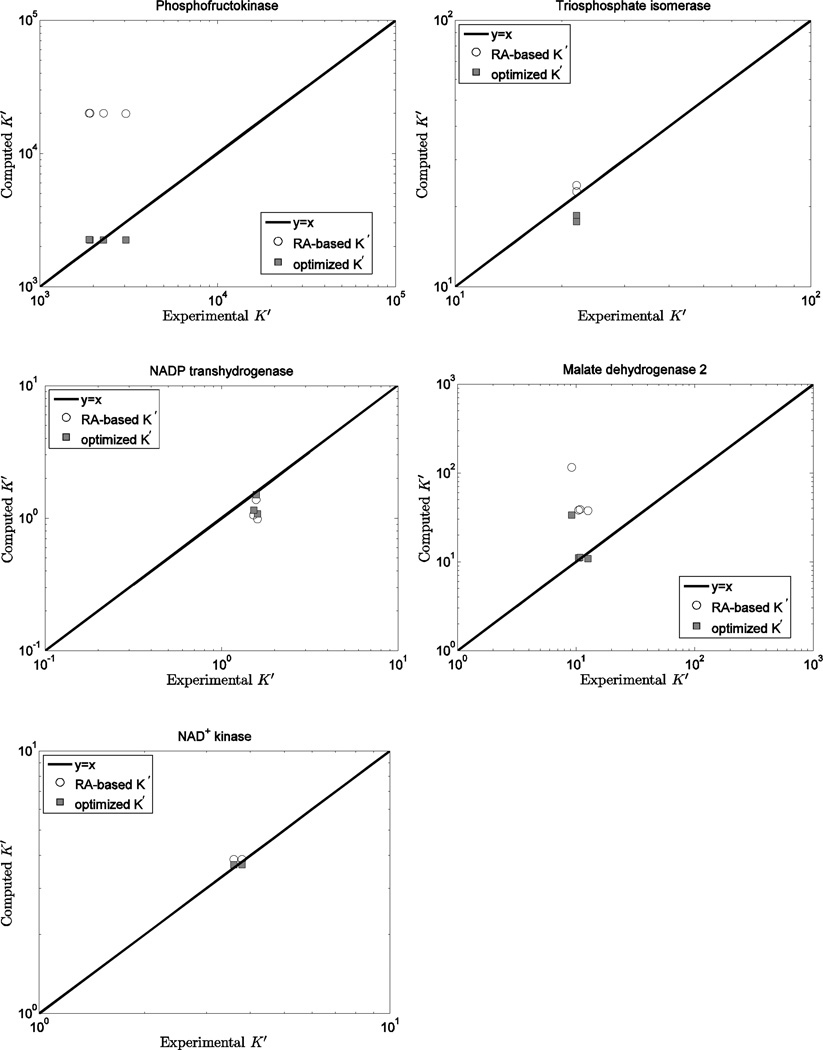

Figure 5.

Computed K’ vs. experimental K’ for the phosphofructokinase, triosphosphate isomerase, NADP transhydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase 2, and NAD kinase reactions. Open circles (RA-based K’) are computed based on the Alberty database 11; filled squares (optimized K’) are computed based on the optimized values of from Table 5 and the fixed values from Table 3.

Figure 4 shows model predictions versus experimental data for the six reactions showing a discrepancy between the current predicted ΔrGo values and those obtained based on the Alberty database. For these cases the current model predictions are consistently closer to the experimental data than those obtained from the Alberty free energy values because the predicted K’ values depend strongly on the experimental ionic composition. Figure 5 illustrates model predictions for five reactions (PFK, MDH2, NPTH, NADK, and TPI) for which four or fewer data entries are available. For the TPI reaction, model predictions based on the Alberty database are slightly better than those based on the current database.

Predicted equilibrium properties

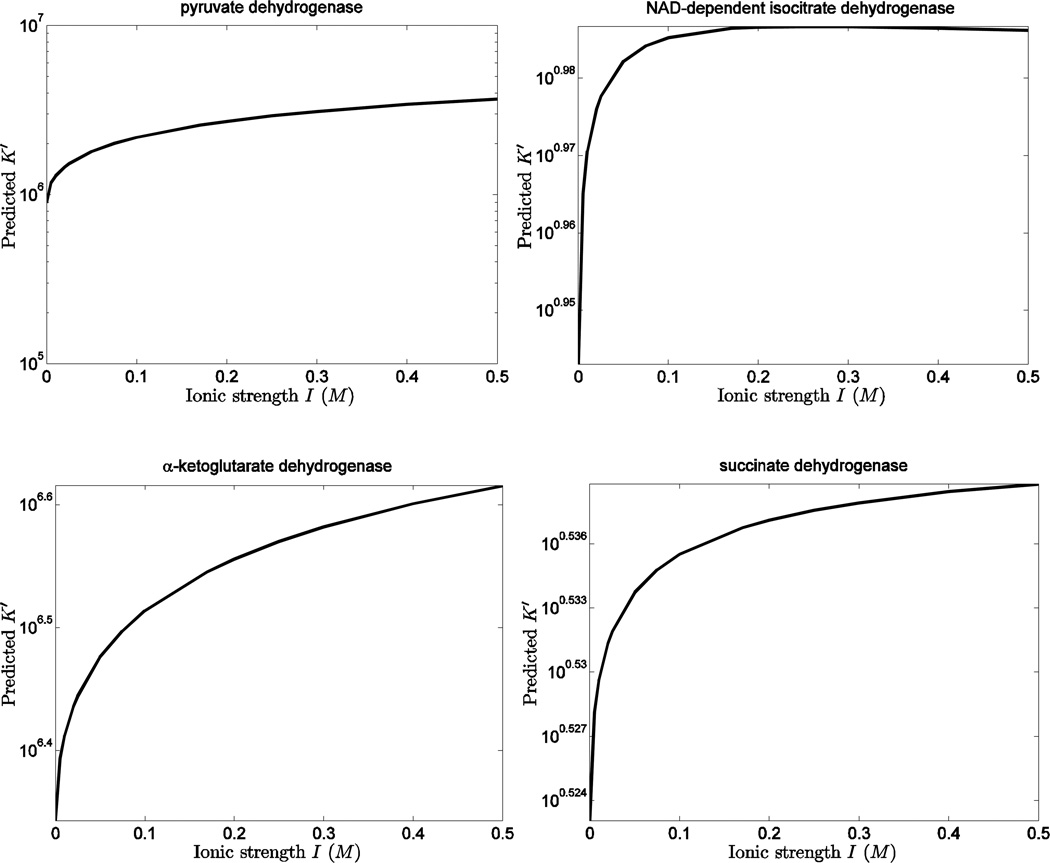

The developed thermodynamic model may be used to estimate equilibrium properties for pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), NAD-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH2), α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (AKGDH), and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)—reactions in the TCA cycle for which direct measurements are not available in the literature. Since the developed thermodynamic database includes estimates of for all of the species in these reactions (with the values in Table 3.2 from Alberty 11), it is possible to estimate ΔrGo and apparent equilibrium properties as functions of ionic strength, temperature, and solution composition.

Table 4 lists the predicted ΔrGo values for all reactions. The differences between the current database predictions and those of Alberty for these four reactions (PDH, IDH2, AKGDH, and SDH) are less than RT at standard temperature. Figure 6 plots predicted values of K’ as functions of ionic strength for these reactions, assuming T = 298.15 K, pH = 7, and no metal cations present. Since the sum of squared charges of products and reactants is equal to zero in the reaction of SDH, the corresponding K is independent of ionic strength. For this reaction the weak dependence of K’ on I is due to the influence of I on the hydrogen ion dissociation constants for succinate and fumarate. For all other reactions, the predicted K’ monotonically increases as ionic strength increases because is positive and the increasing ionic strength leads to decreased ΔrGo according to Equation (4).

Figure 6.

Computed apparent equilibrium constant K’ (at 298.15 K) as a function of ionic strength I of the solution pyruvate dehydrogenase, NAD-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, and succinate dehydrogenase. Calculations assume pH = 7 and no metal cations present.

Predicted apparent Gibbs free energies under physiology conditions

The final column in Table 4 reports the predicted apparent ΔrG′o (= − RT ln K’) at physiological conditions representative of a typical mammalian cell 42,43 (T = 310.15 K, I = 0.18 M, pH = 7, [Mg2+] = 0.8 mM, [K+] = 140 mM, [Na+] = 10 mM, [Ca2+] = 0.0001 mM). For example, the predicted apparent reference Gibbs free energy (ΔrG′o) for ATP hydrolysis is −32.76 kJ/mol, which lies between −34.43 kJ/mol (the value obtained from the Alberty database) and the widely used value of −30.5 kJ/mol 44.

Discussion

We have developed a biochemical thermodynamic database for the reactions of glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle that is optimally self-consistent and consistent with the data available for these reactions. Theoretical predictions of apparent equilibrium constants, based on the estimated species-level Gibbs free energies of formation and accounting for the effects of temperature, ionic interactions, and hydrogen and metal cation binding optimally match experimental data on equilibrium constants.

While this database represents only a small subset of critical biochemical reactions (and indeed a subset of previously available databases, such as that of Alberty 11), it does improve upon previous works in several ways. First, the underlying model accounts for first- and second-order binding of Mg2+, K+, Na+ and Ca2+ ions in the experimental media employed in the various studies from which the raw data were obtained. Since the binding of these ions to biochemical reactants has profound effects on apparent equilibria, incorporation of these effects significantly improves the accuracy of the derived database. Second, all raw data and procedures used to estimate quantities such as ionic strength and metal ion concentrations are archived and made electronically available. The availability of these raw data and computational procedures is crucial to future extensions to the database, since the optimal values of species-level properties are interdependent. Extension of the database to account for reactions (and reactants) not currently in the database will require the recalculation of the entire set of species-level properties.

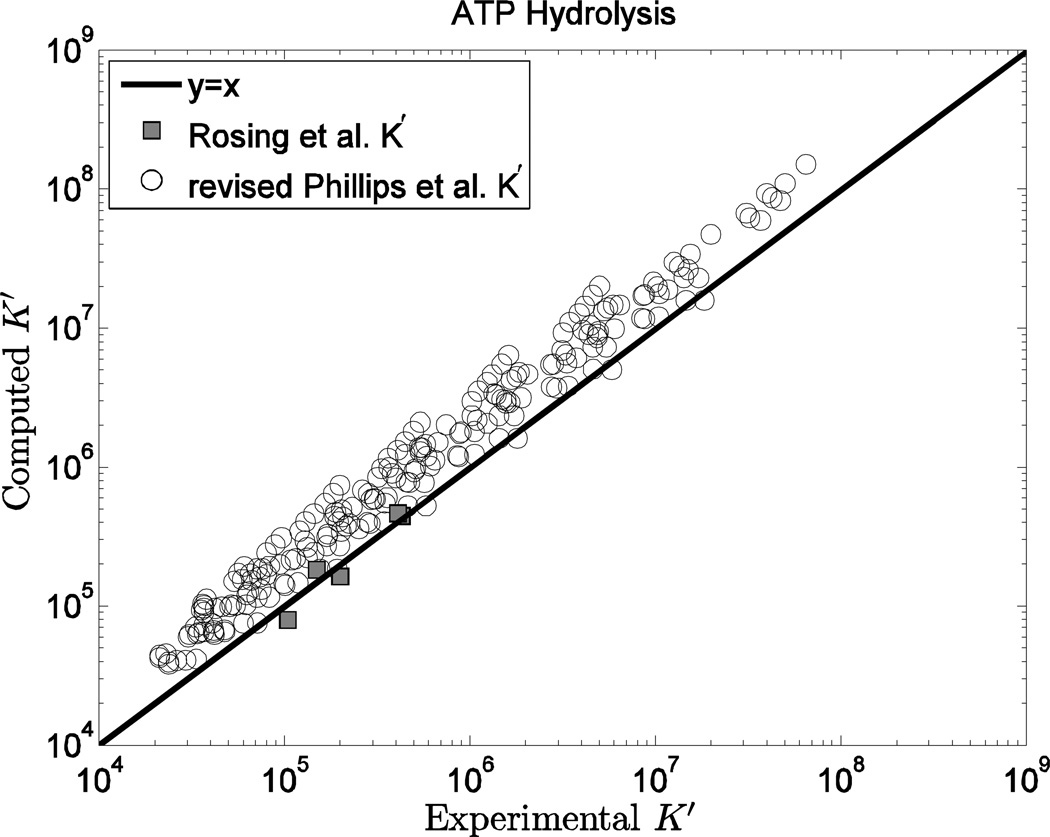

Third, since the establishment of this database requires invoking certain arbitrary choices, the publication of all underlying data allows those choices to be revised by other investigators. For example, for the ATP hydrolysis reaction, the data of Rosing et al. 37 are used rather than the more extensive data set provided by Phillips et al. 45. Thus, while the model predictions agree well with the data of Rosing et al., they do not match the data of Phillips et al. data as well. We chose to use the data of Rosing et al. in our calculations because these data are more consistent with previously established equilibrium properties for this reaction 11 and because, as Rosing et al. point out, the values of the ATP hydrolysis apparent equilibrium constant of Phillips et al. were based on an inaccurate estimate of the equilibrium constant for glutamine synthetase, which was used in a coupled assay for ATP hydrolysis equilibrium constant. Indeed, Rosing et al. applied a series of corrections to the measurements reported by Phillips et al., yielding the data set plotted in Figure 7, which are much more consistent with the Rosing et al. data and the current model predictions than the original Phillips et al. data set. Using the freely available model code and database developed here, one may easily recalculate a set of species-level properties that are consistent with the corrected Phillips et al. data rather than (or in addition to) the Rosing et al. data.

Figure 7.

Computed K’ vs. experimental K’ for the ATP hydrolysis reaction. The values reported by Rosing et al. 37 in the original publication are plotted here along with the data of Phillips et al. 45 corrected and re-republished by Rosing et al. 37.

Therefore this thermodynamic database for glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle provides a framework for future extensions. To date, efforts in this field have largely relied on the work on the Alberty laboratory. Yet, given the tremendous amount of work that is required in parsing the data published in a given study into a useable form, large-scale extensions will necessarily be a community effort. Goldberg and colleagues have provided a rich and expertly curated database of experimental measurements to build this effort around. Making use of their raw-data database for extending the current database of species-level thermodynamic properties will involve characterizing the ionic composition associated with each data entry that may be used in the network optimization-based estimation of species properties. To do this, each original publication must be studied on a case-by-case basis, case-specific assumptions and approximations determined and documented, and case-specific calculations performed and documented.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Robert Goldberg for advice and critical comments. This work was supported by NIH grant HL072011.

Nomenclature

- a

activity

- B

an empirical constant taken to be 1.6 M−1/2

- ΔrGo

standard Gibbs free energy of reaction

standard Gibbs free energy of formation of species i

- ΔdHKd

enthalpy of proton/metal cation dissociation

- ΔrHo

standard enthalpy of reaction

- I

ionic strength

- Kd

dissociation constant

- K’

apparent equilibrium constant

- K

chemical (reference reaction) equilibrium constant

- N

the total number of species

- Pj

binding polynomial associated with reactant j

- pK

negative logarithm of the dissociation constant

- R

gas constant, 8.3145 J·K−1·mol−1

- γ

activity coefficient

- T

temperature

- vi

stoichiometric coefficient for species i in a given reaction

- zi

charge number of species i

Appendix I

Computing Ionic Species Distribution from Reported Data on Buffer Composition

Comparing model-estimated apparent equilibrium constants to measured values (used here to estimate a consistent set of species-level thermodynamic properties) requires estimating the ionic composition of the buffer associated with each measured equilibrium constant value for each reaction. Here information from original reports is synthesized to generate estimated values of free Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ concentrations, overall ionic strength, pH, and temperature, so that these aspects of the biochemical state are quantified for each raw equilibrium data entry in the database. This appendix briefly describes how these calculations are conducted for two example reactions.

Example 1

Data for Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (EC 5.3.1.9) were obtained from Tewari et al. 39, which reported equilibrium constants of [∑ F6P]/[∑ G6p] at several different temperatures and ionic conditions. Several different total concentrations of Tris buffer were used to obtain reported pH values of 8.7, as reported in Table A1. The valued listed in the table under Reported Conditions were used to estimate the total concentrations reported under Computed Total Concentrations, using the following steps:

- The concentration of H+-ion bound Tris ([Tris.H+]) was computed assuming that Tris does not significantly bind magnesium or sodium ions at the given concentrations:

The Tris H+-ion dissociation was assumed to have a pK value of pKH = 8.072, as reported by Tewari et al. 39. Added [HCl] used to obtain the reported pH was estimated to be equal to [Tris.H+]. Thus total chloride ion ([Cl−]tot) was computed from the sum [Cl−]tot = [Tris.H+] + 2[MgCl2].

Hexose-6P sugars were added as disodium salts in the range 34–55 mM. The calculations here take the average concentration (44.5 mM) to obtain total added sodium ion of 0.089 M. The total hexose-6-phosphate [H6P]tot refers to total [∑ F6P]/[∑ G6P].

Table A1.

Experimental conditions from Tewari et al.39

| Reported Conditions | Computed Total Concentrations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (K) | pH | [Tris] (M) | [MgCl2] (M) | K’ | [Tris.H+] (M) | [Cl−]tot (M) | [Mg2+]tot (M) | [H6P]tot (M) | [Na+]tot (M) |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.001 | 0.293 | 0.0191 | 0.0211 | 0.0010 | 0.0445 | 0.089 |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.3 | 0.001 | 0.299 | 0.0572 | 0.0592 | 0.0010 | 0.0445 | 0.089 |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.64 | 0.001 | 0.302 | 0.122 | 0.124 | 0.0010 | 0.0445 | 0.089 |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0001 | 0.287 | 0.0191 | 0.0193 | 0.0001 | 0.0445 | 0.089 |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0010 | 0.293 | 0.0191 | 0.0211 | 0.0010 | 0.0445 | 0.089 |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0025 | 0.308 | 0.0191 | 0.0241 | 0.0025 | 0.0445 | 0.089 |

| 304.95 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0001 | 0.310 | 0.0191 | 0.0193 | 0.0001 | 0.0445 | 0.089 |

| 310.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0001 | 0.329 | 0.0191 | 0.0193 | 0.0001 | 0.0445 | 0.089 |

| 316.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0001 | 0.357 | 0.0191 | 0.0193 | 0.0001 | 0.0445 | 0.089 |

Given the total concentrations reported in Table A1, the free unbound concentrations of magnesium ion and [H6P2−] for each entry are calculated from solving the following mass balance equations:

where the two hexose-6-phosphate sugars are lumped into a single representative reactant, assumed to have the same H+- and Mg2+-dissociation properties:

These mass balance equations assume that Na+ and Cl− ions are fully unbound in these experiments. The values of pKH_H6P and pKMg_H6P are taken as 5.8275 and 1.6150, respectively, corresponding to values in Table 2, adjusted for ionic strength of 0.153 M, which is close to the value of I estimated for the data entries from Tewari et al. The assumption that G6P and F6P have equivalent H+- and Mg2+-dissociation properties is consistent with the pK values adopted in this study.

The resulting computed free ion concentrations and ionic strengths are listed in Table A2. The ionic strength of the solution is calculated by the following equation:

Table A2.

Estimated free ion concentrations and ionic strength for data from Tewari et al.39

| T (K) | pH | [Tris] (M) | [MgCl2] (M) | K’ | [H6P2−] (M) | [H.H6P−] (M) | [Cl−] (M) | [Mg2+] (M) | [Na+] (M) | I (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.001 | 0.293 | 0.0438 | 5.87E-05 | 0.0211 | 3.57E-04 | 0.089 | 0.153 |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.3 | 0.001 | 0.299 | 0.0438 | 5.87E-05 | 0.0592 | 3.57E-04 | 0.089 | 0.191 |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.64 | 0.001 | 0.302 | 0.0438 | 5.87E-05 | 0.124 | 3.57E-04 | 0.089 | 0.256 |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0001 | 0.287 | 0.0444 | 5.95E-05 | 0.0193 | 3.54E-04 | 0.089 | 0.153 |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0010 | 0.293 | 0.0438 | 5.87E-05 | 0.0211 | 3.57E-04 | 0.089 | 0.153 |

| 298.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0025 | 0.308 | 0.0428 | 5.75E-05 | 0.0241 | 9.04E-04 | 0.089 | 0.154 |

| 304.95 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0001 | 0.310 | 0.0444 | 5.95E-05 | 0.0193 | 3.54E-04 | 0.089 | 0.153 |

| 310.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0001 | 0.329 | 0.0444 | 5.95E-05 | 0.0193 | 3.54E-04 | 0.089 | 0.153 |

| 316.15 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 0.0001 | 0.357 | 0.0444 | 5.95E-05 | 0.0193 | 3.54E-04 | 0.089 | 0.153 |

Example 2

Data for phosphoglycerate mutase (EC 5.4.2.1) are obtained from Guynn 40, in which equilibrium was approached from both sides of the reaction at various concentrations of magnesium and added KCl to reach a target ionic strength of 0.25 in a 25 mM phosphate buffer at a temperature of 311.15 K. Total final PG2, PG3, added magnesium in the form of MgCl2, and measured final pH were reported. The phosphoglycerates and inorganic phosphate in the solution exist in unbound anionic forms, proton, magnesium and potassium ion bound forms.

In this example, the solution composition may be computed by applying both mass and charge conservation equations, as follows. For each biochemical measurement entry, the total added magnesium is fixed at a constant given by the reported added MgCl2.

The ionic strength of the solution was adjusted to the specified value of Itarget = 0.25 M:

The total charge in the system must be conserved:

The unknowns determined in this system are [Mg2+], [K+], and [Cl−]. The ionic species concentrations in these three conservation equations are computed as functions of the free ion concentrations and the total biochemical reactant concentrations based on the dissociation constants reported in Table 3, adjusted to T = 311.15 K and I = 0.25 M.

Note that both total and free [K+] exceed [Cl−] because the phosphoglycerates were added as potassium salts and the 25 mM phosphate buffer is based on potassium salts of phosphate.

Appendix II

Estimating the standard reaction enthalpy (ΔrHo) from experimentally measured apparent equilibrium constants (K’)

Measurements of apparent equilibrium constants at different temperatures are available in the raw-data database for 10 of the 25 reactions studied here (as shown in Table 1 in the paper). For these cases apparent equilibrium constants measured at multiple temperatures allow for direct estimates of the reaction enthalpy. To obtain ΔrHo, we first compute ionic species distribution and ionic strength of buffer under experimental conditions as described in Appendix I, and then compute the equilibrium constants of corresponding reference reactions at zero ionic strength based on procedure listed in the Methods. By assuming that ΔrHo is independent of temperature over experimental temperature ranges, we can obtain ΔrHo from the linear relationship between ln(K) and 1/T (i.e., van’t Hoff relationship):

| (A1) |

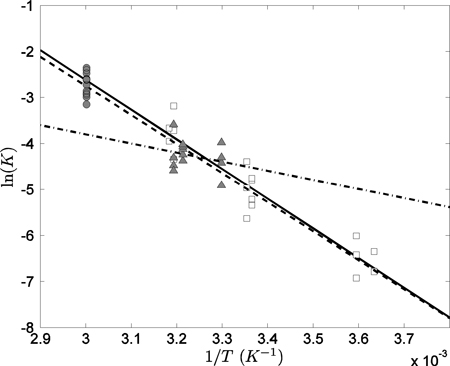

Examples of computing ΔrHo of the reactions of fructose-1,6-biophosphatate aldolase (FBA), fructose-1,6-biophosphatate aldolase 2 (FBA2), and triosphosphate isomerase (TPI) are illustrated below.

Example 1

The biochemical reactions of FBA, FBA2, and TPI are shown in Table 1. Literature-reported K’ of reactions of FBA and FBA2 are available in the Goldberg et al. database 27, which includes the K’ of FBA2 measured by Utter et al. 46 at multiple temperatures ranging from 275.15 to 314.15 K, and the K’ of FBA and FBA2 determined by Meyerhof et al. 47 at temperatures ranging from 303.15 K to 333.15 K. Ion concentrations are estimated based on specified experimental conditions, and reference-reaction equilibrium constants at zero ionic strength K estimated for the Utter et al. and Meyerhof et al. measurements.

Linear regressions of ln(K) versus 1/T are plotted in Figure A1 as solid lines along with data for FBA and FBA2. The ΔrHo for FBA and FBA2 are computed from the slopes according to Equation (A1). Because the TPI reaction is stoichiometrically equivalent to the combination of FBA and FBA2, the associated ΔrHo is computed as

Figure A1: Plot of ln(K) versus 1/T for the fructose-1,6-biphosphatate aldolase (FBA and FBA2) reactions. The data points plotted as solid circles to correspond to I = 0. The reaction enthalpies are obtained by multiplying the slope of fitted line by −R.

These values of ΔrHo are based on data from Meyerhof et al. that were obtained at temperatures as high as 333.15 K, which exceeds the defined valid temperature range (273.15 K to 313.15 K) of the extended Debye-Hückel theory 11,31,33. To investigate the validity of including of the 333.15K data in the computation, let us perform linear regressions for FBA2 reaction for different sets of datasets, including the Utter et al. data (dataset 1), the Meyerhof et al. data including the high-temperature data (dataset 2), and the Meyerhof et al. data excluding the high-temperature data (dataset 3). The linear regressions for the three datasets are plotted as solid, dashed, and dot-dash lines, respectively, in Figure A2, and the corresponding computed ΔrHo are 53.59, 52.52, and 16.34 kJ/mol. Because the difference in estimated ΔrHo between dataset 1 and dataset 2 is much smaller than that between dataset 1 and dataset 3, and because dataset 1 is obtained with the well-defined temperature range, we conclude that the inclusion of Meyerhof et al. high-temperature data improves accuracy of the estimation of ΔrHo. Thus we choose to include the Meyerhof et al. high-temperature (333.15K) data in estimating ΔrHo for FBA and FBA2.

Figure A2: Comparison of Utter et al. 46 and Meyerhof et al. 47 data for the FBA2 reaction. The Utter et al. data are plotted as open squares, and the Meyerhof et al. data are plotted as solid circles for the high-temperature data and as solid triangles for low-temperature data. The linear fit for dataset 1 is plotted as a solid line, dataset 2 a dashed line, and dataset 3 a dot-dash line, where datasets 1, 2, and 3 are defined in Appendix II.

Table A3.

Estimated free ion concentrations and ionic strength for data from Guynn40

| pH | [PG3tot] (mM) | [PG2tot] (mM) | [Mgtot] (mM) | [Mg2+] (mM) | [K+] (mM) | [Cl−] (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.76 | 1.9 | 0.178 | 1 | 0.670 | 235.1 | 198.0 |

| 6.78 | 1.86 | 0.174 | 1 | 0.668 | 235.0 | 197.8 |

| 6.86 | 0.969 | 0.092 | 1 | 0.673 | 235.8 | 200.1 |

| 6.83 | 0.995 | 0.088 | 1 | 0.676 | 236.0 | 200.5 |

| 6.66 | 1.8 | 0.172 | 7.3 | 5.111 | 223.6 | 199.0 |

| 6.65 | 1.74 | 0.164 | 7.3 | 5.129 | 223.7 | 199.4 |

| 6.79 | 0.942 | 0.092 | 7.3 | 5.084 | 223.9 | 200.2 |

| 6.76 | 0.951 | 0.084 | 7.3 | 5.114 | 224.0 | 200.6 |

| 6.57 | 1.8 | 0.166 | 13.7 | 9.941 | 210.3 | 198.4 |

| 6.68 | 1.7 | 0.157 | 13.7 | 9.752 | 210.2 | 197.3 |

| 6.72 | 0.898 | 0.086 | 13.7 | 9.855 | 210.7 | 199.5 |

| 6.7 | 0.934 | 0.085 | 13.7 | 9.884 | 210.7 | 199.7 |

| 6.48 | 1.73 | 0.160 | 20 | 15.002 | 196.2 | 197.1 |

| 6.48 | 1.72 | 0.157 | 20 | 15.083 | 196.0 | 197.1 |

| 6.65 | 0.89 | 0.082 | 20 | 14.798 | 196.7 | 198.0 |

| 6.63 | 0.963 | 0.085 | 20 | 14.828 | 196.7 | 197.9 |

References

- 1.Vojinović V, von Stockar U. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2009;103:780. doi: 10.1002/bit.22309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg RN, Tewari YB, Bell D, Fazio K, Anderson E. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1993;22:515. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuster R, Schuster S. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1993;9:79. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/9.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonarius HPJ, Schmid G, Tramper J. Trends in Biotechnology. 1997;15:308. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mavrovouniotis ML. Identification of localized and distributed bottlenecks in metabolic pathways; Proceedings of the 1st Int. Conf. on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology; Bethesda, MA: AAAI; 1993. p. 275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang F, Beard DA. Biophysical Chemistry. 2006;120:121. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kümmel A, Panke S, Heinemann M. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100074. 2006.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry CS, Broadbelt LJ, Hatzimanikatis V. Biophysical Journal. 2007;92:1792. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinnakota KC, Wu F, Kushmerick MJ, Beard DA. Methods Enzymol. 2009;454:29. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03802-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinnakota K, Kemp ML, Kushmerick MJ. Biophys J. 2006;91:1264. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alberty RA. Thermodynamics of Biochemical Reactions. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Interscience; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alberty RA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:3268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alberty RA. Biophys Chem. 1992;42:117. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(92)85002-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberty RA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1207:1. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alberty RA. Biophys Chem. 2005;114:115. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alberty RA. Biophys Chem. 2006;122:74. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alberty RA. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15838. doi: 10.1021/bi061829e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alberty RA. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;451:17. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberty RA. Biophys Chem. 2007;127:91. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg RN, Tewari YB, Bhat TN. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2874. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu F, Yang F, Vinnakota KC, Beard DA. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:24525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi F, Chen X, Beard DA. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins & Proteomics. 2008;1784:1641. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu F, Zhang J, Beard DA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:7143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812768106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg RN, Tewari YB. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1989;18:809. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberg RN, Tewari YB. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1994;23:547. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldberg RN, Tewari YB. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1994;23:1035. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg RN, Tewari YB. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1995;24:1669. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg RN, Tewari YB. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1995;24:1765. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg RN. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1999;28:931. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg RN, Tewari YB, Bhat TN. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 2007;36:1347. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beard DA, Qian H. Chemical Biophysics: Quantitative Analysis of Cellular Systems. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2008. Conventions and calculations for biochemical systems; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alberty RA. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2006;110:5012. doi: 10.1021/jp0545086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke ECW, Glew DN. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1. 1980;76:1911. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alberty RA. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2001;105:7865. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alberty RA. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2001;105:1109. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alberty RA. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2005;109:9132. doi: 10.1021/jp044162j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosing J, Slater EC. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1972;267:275. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(72)90116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobson GP, Hitchins S, Teague WE., Jr J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tewari YB, Steckler DK, Goldberg RN. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:3664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guynn RW. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1982;218:14. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vanlier J, Wu F, Qi F, Vinnakota KC, Han Y, Dash RK, Yang F, Beard DA. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:836. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guyton AC, Hall JE. Textbook of Medical Physiology. W. B. Saunders; 2000. Transport of substances through the cell membrane; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Godt RE, Maughan DW. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1988;254:C591. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.5.C591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kammermeier H, Schmidt P, Jüngling E. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1982;14:267. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(82)90205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips RC, George SJP, Rutman RJ. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1966;88:2631. doi: 10.1021/ja00964a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Utter MF, Werkman CH. J. Bacteriol. 1941;42:665. doi: 10.1128/jb.42.5.665-676.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyerhof O, Junowicz-Kocholaty R. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1943;149:71. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martell AE, Smith RM, Motekaitis RJ. NIST Standard Reference Database 46 Version 8.0: NIST Critically Selected Stability Constants of Metal Complexes. Gaithersburg, MD: NIST Standard Reference Data; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alberty RA. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1995;99:11028. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tewari YB, Steckler DK, Goldberg RN, Gitomer WL. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:3670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Larsson-Raźnikiewicz M. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1972;30:579. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb02129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merrill DK, McAlexander JC, Guynn RW. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1981;212:717. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]