Abstract

Context

Epidemiologic studies have suggested an association between alcohol consumption and pancreatitis, although the exact dose-response relationship is unknown. It also remains uncertain whether a threshold effect exists.

Objective

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies on the association between alcohol consumption and the risk of pancreatitis.

Methods

We searched Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, ETOH and AIM. Studies were included if they reported quantifiable information on risk and related confidence intervals with respect to at least three different levels of alcohol intake.

Results

Six studies, including 146,517 individuals with 1,671 cases of pancreatitis, met the inclusion criteria. We found a monotonic and approximately exponential dose-response relationship between average volume of alcohol consumption and pancreatitis. However, in a categorical analysis the lower drinking categories were not significantly elevated, with an apparent threshold of 4 drinks daily.

Conclusions

As the available evidence also indicates that the relationship is biologically plausible, these results support the existence of a link between alcohol consumption and the risk of pancreatitis.

Keywords: Alcohol Drinking, Epidemiologic Studies, Humans, Meta-Analysis as Topic, Pancreas

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatitis, inflammation of the pancreas, has two forms. Acute pancreatitis is an acute inflammatory process of the pancreas that frequently involves peripancreatic tissues and/or remote organ systems. Chronic pancreatitis is defined as an inflammatory process that leads to the progressive and irreversible destruction of exocrine and endocrine glandular pancreatic parenchyma which is substituted by fibrotic tissue [1, 2]. Recent data from predominantly Western countries have shown an increasing trend in the incidence of acute pancreatitis and the number of hospital admissions for both acute and chronic pancreatitis [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. This trend is disconcerting given that pancreatitis places a substantial financial burden on national health care systems. For example, a recent U.S. study [8] estimated that the total cost for acute pancreatitis hospitalizations in 2003 was $2.2 billion (95% CI: $2.0–2.3 billion) at a mean cost per hospitalization of $9,870 (95% CI: $9,300–10,400), and a mean cost per hospital day of $1,670 (95% CI; 1,620–1,720).

It has long been recognized that alcohol consumption is a modifiable risk factor for pancreatitis [9, 10]. There is also evidence for a link between alcohol consumption and the development of both acute and chronic pancreatitis [11]; for both acute and chronic pancreatitis there are ICD subcategories with the specification of alcoholic (K85.2; K86.0). However, the precise magnitude of the impact of alcohol on the underlying dose-response relationship remains poorly quantified [12]. Not only the shape of the dose-response relationship in general, but also the particular question whether pancreatitis is part of the disease categories, which where there is a threshold for the effect of alcohol consumption or not, has not been clarified. The answer to this question not only contributes to etiological research, but also has potential preventive implications.

In general, epidemiological studies on the quantitative aspects of risk estimations for pancreatitis in relation to alcohol are scarce. In 2004, Corrao et al. [13] conducted a meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies published between 1966 and 1995 that assessed the association between alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases, including pancreatitis. Only two case-control studies provided data on pancreatitis.

Results from the pooled analysis of the two studies showed that the risk of pancreatitis increased monotonically with increasing alcohol consumption, with no apparent threshold. Reported relative risks associated with alcohol intake of 25, 50, and 100 g/day were 1.3 (95% CI: 1.2–1.5), 1.8 (95% CI: 1.3–2.4), and 3.2 (95% CI: 1.8–5.6) respectively, compared to non-drinkers [13].

Since the meta-analysis by Corrao et al. [13], additional epidemiological studies have been published that address the association between alcohol consumption and the risk of pancreatitis. The present systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to analyze the studies published between 1980 and 2008 to update and quantitatively assess the association between alcohol consumption and the risk of pancreatitis. We also sought to address the unresolved issue of whether there is a threshold of alcohol use associated with the risk of pancreatitis.

METHODS

Literature Search

We performed a systematic search of Ovid MEDLINE (http://www.ovid.com/site/catalog/DataBase/901.jsp), EMBASE (http://www.embase.com/), CINAHL (http://www.ebscohost.com/cinahl/), Web of Science (www.isiknowledge.com/), ETOH (http://etoh.niaaa.nih.gov/) and AIM (http://www.aim-digest.com/gateway/m%20index.htm) to identify epidemiologic studies published from January 1980 to January 2008 that assessed the association between alcohol consumption and risk of pancreatitis. The search was conducted using any combination of the key words: alcohol, alcohol consumption, alcohol intake, ethanol, heavy drinking, and pancreatitis. In addition, we manually reviewed the content pages of the major epidemiological journals and the reference lists of relevant and review articles. The search was limited to human studies and no language restrictions were applied.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Our inclusion criteria required studies to: 1) have a case-control or cohort study design; 2) report hazard ratios (HR), relative risks (RR) or odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (or information allowing us to compute them); 3) have pancreatitis morbidity and/or mortality as defined above as the endpoint; and 4) include three or more quantitatively measured exposure categories of alcohol consumption. Studies were excluded if: 1) they were not published as full reports, such as conference abstracts and letters to editors; 2) a cross-sectional design was used; 3) a continuous measure of alcohol consumption was included.

Pancreatitis Ascertainment

Death, hospitalization for, or diagnosis of acute or chronic pancreatitis was defined using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. For acute pancreatitis, the codes were 577.0 in ICD-8 and 9 and K85 in ICD-10. For chronic pancreatitis, the codes were 577.1 in ICD-8 and 9 and K86.0 and K86.1 in ICD-10. Diagnosis of acute or chronic pancreatitis was generally based on clinical history and the findings of pancreatic imaging procedures such as ultrasonography and radiographic computed tomography. Cases of acute and chronic pancreatitis were pooled together for the purposes of analysis in this meta-analysis due to the scarcity of studies. The decision to combine acute and chronic pancreatitis seems justifiable since clinically, the two conditions can co-exist, as acute pancreatitis often occurs in patients with chronic pancreatitis [2, 14]. Furthermore, it is difficult, in epidemiological studies, to distinguish between chronic and acute pancreatitis as case ascertainment most often relies on routinely collected secondary data [15].

Data Extraction

Data extracted from each study included the first author's name, year of publication, sample size, country, age, sex, endpoints, adjustments, study design, exposure and outcome measures, RRs of pancreatitis and corresponding 95% CIs for each category of alcohol consumption. When ranges of alcohol categories were reported, the midpoint was recorded. If the upper bound for the highest category was not provided, 75% of the width of the preceding category's range was added to the lower bound to derive the midpoint. Throughout this paper, RR is used to refer to all risk estimates including, ORs, RRs, or HRs.

ETHICS

Data for this meta-analysis were derived from systematic reviews of published studies. Ethical review was therefore not necessary.

STATISTICS

To assess the dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and risk of pancreatitis, we used the method proposed by Greenland and Longnecker [16] and Orsini and Greenland [17] to back-calculate and pool the risk estimates. For outcome, we used the logarithmized RR and for exposure, we used the midpoints described above. To derive the dose-response curve, we fitted a family of first and second degree fractional polynomial models [18]. All models were fitted using DerSimonian and Laird [19] random-effects models. The best fitting model was selected based on a closed-test comparison between fractional polynomial models [18] and overall model fit was assessed using the Cochrane Q statistic [20].

Regression analyses may give distorted results for categories, where no or few data points exist, as it tries to minimize the overall deviation of data points from the regression line. Categorical analyses can give a better indication on the risk for specific categories, and thus is better suited to detect thresholds. To examine whether a threshold exists, that is, a level of alcohol consumption under which the risk of pancreatitis was not increased, we also modeled alcohol intake as a categorical variable using the following categories: 0 (reference group), more than 0 to 2, more than 2 to 4, and more than 4 drinks daily. A drink was equivalent to 12 grams. We assigned the level of alcohol consumption from each study to these categories based on the calculated midpoint of alcohol consumption. Dummy variables were generated and they were included in the categorical meta-analysis to assess the possibility of threshold effects across alcohol consumption categories.

Statistical heterogeneity between studies was examined using both the Cochrane Q statistic and the I2 value. I2 ranges between 0% and 100%, and values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered to represent low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [20, 21]. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of Begg's funnel plot (based on the linear effect), the Begg-Mazumdar [22] adjusted rank correlation test and the Egger regression asymmetry test for funnel plot [23]. All statistical analyses were completed using Stata Version 10.1 [24].

RESULTS

Characteristics of Included Studies

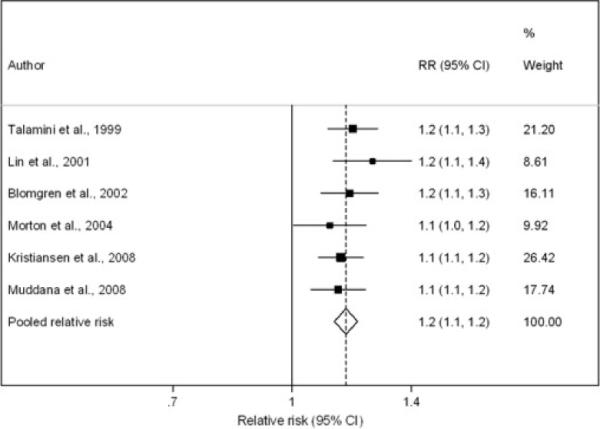

The search identified 2,712 potentially relevant publications and 2,588 were excluded on the basis of titles and abstracts (generally because there was no indication of a relationship between alcohol consumption and pancreatitis). Of the remaining 124 potentially relevant papers; only 6 studies met our inclusion criteria [15, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. Of the 6 studies, two used a cohort design and the remaining four employed a case-control design. Alcohol exposure data were collected via self-administered questionnaires in three studies [15, 27, 29] and by interview administered questionnaires in the remaining studies [25, 26, 28]. The highest categories of alcohol consumption varied across the included studies. In the Morton et al. study [28], the highest alcohol consumption category was greater than 36 g/day, whereas in the study by Lin et al. [27], the corresponding figure was greater than 100 g/day. In the studies by Talamini et al. [26] and Kristiansen et al. [15], the highest categories were 41–80 g/day and greater than 82 g/day, respectively. In the remaining two studies (Blomgren et al. [25] and Muddana et al. [29]) the highest category of alcohol intake was greater than 60 g/day. Collectively, the 6 studies included 146,517 individuals with 1,671 cases of pancreatitis. Figure 1 shows the contribution of individual studies based on the assumptions of a linear effect, i.e., that the RR per drink remains constant over the full range of exposure.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author (total study population) | Country | Study design | Outcome | Outcome assessment | Adjustments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talamini et al., 1999 [26] (782 men) | Italy | Case-control | Hospital based patients with chronic pancreatitis (n=169) | Clinical symptoms, and the findings of pancreatic imaging procedures such as ultrasonography, radiographic computed tomography | Age via sampling; smoking via regression |

| Lin et al., 2001 [27] (244 men) | Japan | Case-control | (Incident) newly diagnosed hospitalization with chronic pancreatitis (n=87) | Clinical symptoms, and the findings of pancreatic imaging procedures such as ultrasonography, radiographic computed tomography | Age via sampling; BMI, education level, smoking via regression |

| Blomgren et al., 2002 [25] (2,243 women and men) | Sweden | Case-control (population-based) | First episode of acute pancreatic without previously known gallstone disease (n=462) | Clinical symptoms, and the findings of pancreatic imaging procedures such as ultrasonography, radiographic computed tomography | Age and sex via sampling |

| Morton et al., 2004 [28] (124,740 women and men) | U.S.A. | Cohort | First hospital admission (not necessarily first lifetime admission) for any form of pancreatitis (n=407) | Hospital discharge records; death certificates; ICD-code 577 | Age, sex, and race via sampling; BMI, education via regression |

| Kristiansen et al., 2008 [15] (17,905 women and men) | Denmark | Cohort | Mortality or hospitalization due to acute or chronic pancreatitis (n=235) | Hospital discharge records; death certificates; ICD-8 & ICD-9 codes | Age, sex, smoking, education, and body mass index via regression |

| Muddana et al., 2008 [29] (603 women and men) | U.S.A. | Case-control | Hospital patients with either recurrent acute pancreatitis or chronic pancreatitis (n=311) | Clinical symptoms, and the findings of pancreatic imaging procedures such as ultrasonography, radiographic computed tomography | Age and sex via sampling |

Figure 1.

Forest plot of individual studies based on one drink (12 grams) daily.

Dose-Response Relationship

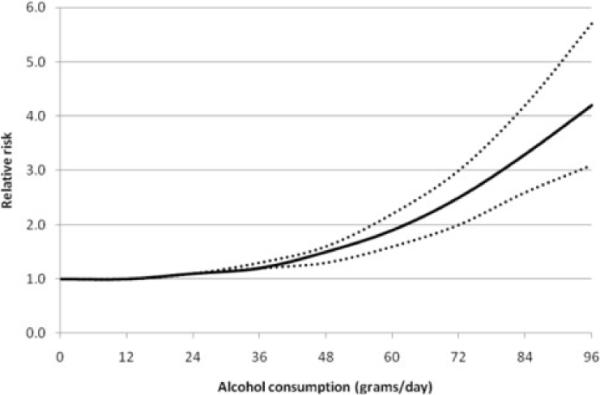

Using the methods described above, we chose a second degree model, which proved to be significantly better than a simple linear model (P=0.003). The model fit statistic revealed that this model fitted the data reasonably well (Q-test=35.69, df=22, P=0.033; I2=38%, 95% CI: 0–63%). The fitted dose-response relationship is depicted in Figure 2. Overall, the results indicate a nonlinear association between alcohol consumption and the relative risk of pancreatitis. The risk curve between alcohol consumption and pancreatitis was relatively flat at low levels of alcohol consumption and it increased markedly with increasing levels of consumption. Individuals consuming 36 grams of alcohol daily, or about three standard drinks such as three cans of beer, had a relative risk of 1.2 (95% CI: 1.2–1.3), compared with non-drinkers. Whereas, those with a daily alcohol intake of 96 grams, or eight standard drinks, had a four-fold increased risk of pancreatitis (RR=4.2, 95% CI: 3.1–5.7), again relative to non-drinkers.

Figure 2.

Dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and risk of pancreatitis (continuous analysis using fractional polynomials). Reference category is non-drinkers; solid line represents the estimated relative risks and the dotted lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

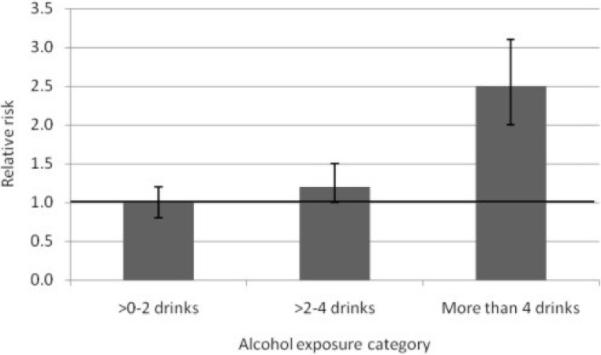

Categorical Analysis

Figure 3 presents the results from the categorical analysis that was performed on the respective alcohol exposure categories to determine whether, on average, low consumption of alcohol entailed any risk at all. Compared with non-drinkers, alcohol consumption of two or fewer drinks per day was not significantly associated with the risk of pancreatitis (RR=1.0, 95% CI: 0.8–1.2; P=0.887). In fact, the risk of drinking two or fewer drinks on average per day was almost identical to the risk of non-drinkers. Those who consumed three to four drinks per day had a 20% increased risk of pancreatitis (RR=1.2, 95% CI: 1.0–1.5, P=0.059), compared with non-drinker, but the difference was only marginally near the significant limit. However, compared with non-drinkers, alcohol consumption of more than 4 drinks per day was significantly associated with the increased risk of pancreatitis (RR=2.5, 95% CI: 2.0–3.1, P<0.001).

Figure 3.

Relative risk of pancreatitis by alcohol exposure category (categorical analysis). Horizontal line represents the relative risk for the reference group, non-drinkers; vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals; 1 drink = 12 grams.

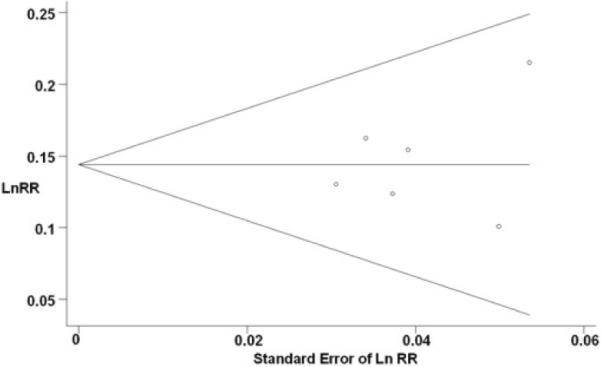

Publication Bias

Figure 4 displays a Begg's funnel plot for the visual assessment of publication bias. The plot was symmetrical, indicating no evidence of publication bias. Likewise, both the Begg-Mazumdar (P=0.851) and Egger (P=0.578) tests suggested no significant asymmetry of the funnel plot, indicating no evidence of substantial publication bias.

Figure 4.

Begg's funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits. Funnel plot shows the relative risks (for 12 g/day) on a natural logarithm scale on its standard error for the six studies included in the meta-analysis. The horizontal line represents the summary estimate of relative risks and the diagonal lines indicate the expected 95% confidence intervals for a given standard error.

DISCUSSION

Using data from recently published epidemiologic studies, the present meta-analysis found a monotonic dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of pancreatitis. This finding is consistent with the results from the previous meta-analysis by Corrao et al. [13]. A completely novel finding in our study was the existence of a threshold effect between alcohol intake and the risk of pancreatitis. The threshold of alcohol associated with the risk of pancreatitis was about 4 drinks daily.

Plausible Pathways

The association between alcohol consumption and pancreatitis is biologically plausible. Ethanol has numerous deleterious effects on the pancreas, including direct toxicity to pancreatic cells as well as changes of production, rheological properties and flow of pancreatic juice, that cause pathological alterations [2, 30, 31, 32]. Specifically, ethanol is metabolized by two different pathways: oxidative and non-oxidative. The major byproducts of the oxidative metabolic pathway are acetaldehyde and the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Non-oxidative metabolism of ethanol is characterized by its esterification with the formation of fatty acid ethyl esters. All three byproducts of ethanol metabolism are known to exert a number of toxic effects on pancreatic acinar cells [30]. In summary, there are several pathophysiological pathways that synergically contribute to alcohol-induced pancreatitis. These include mechanical obstruction of pancreatic ducts and pancreatic autodigestion; pancreatotoxic effects of ethanol metabolites (acetaldehyde, ROS, fatty acid ethyl esters) and pancreofibrosis.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of the present study was the modeling of alcohol consumption as both a continuous and a categorical variable. As a meta-analysis of published studies, we were exposed to potential publication bias. However, publication bias is unlikely to explain the observed association between alcohol consumption and the risk of pancreatitis. Results from our tests of publication bias in this meta-analysis suggested that there was no evidence of publication bias. Our study has a number of limitations that need to be taken into account when considering its contributions. First, our meta-analysis included a limited number (n=6) of studies. Nevertheless, the 6 studies included 14,6517 individuals with 1,671 cases of pancreatitis. Second, the control group (reference category) was non-drinkers. It is likely that this group included a number of former drinkers who stopped drinking because of the presence of pancreatitis, i.e., the sick quitter effect [33]. In this study, misclassification of the control group would lead to the underestimation rather than the overestimation of the true risk of alcohol consumption associated with pancreatitis, however. Third, only one of the six studies provided data on drinking patterns and beverage type. Consequently, we did not have sufficient data to assess the risk of pancreatitis associated with these other dimensions of alcohol consumption.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study provides evidence supporting both a threshold effect and a dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of pancreatitis. In addition, the available evidence indicates that the relationship is biologically plausible. These results support the existence of a link between alcohol and the risk of pancreatitis.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA contract# HHSN267200700041C: “Alcohol- and Drug-Attributable Burden of Disease and Injury in the U.S.” to JR) and the Global Burden of Disease and Injury 2005 Project for financial and technical support for this study

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors have no competing conflicts of interests to declare

References

- 1.Spanier BW, Dijkgraaf MG, Bruno MJ. Epidemiology, aetiology and outcome of acute and chronic pancreatitis: An update. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:45–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.10.007. PMID 18206812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tattersall SJ, Apte MV, Wilson JS. A fire inside: current concepts in chronic pancreatitis. Intern Med J. 2008;38:592–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01715.x. PMID 18715303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frossard JL, Steer ML, Pastor CM. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2008;371:143–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60107-5. PMID 18191686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldacre MJ, Roberts SE. Hospital admission for acute pancreatitis in an English population, 1963–98: database study of incidence and mortality. BMJ. 2004;328:1466–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1466. PMID 15205290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Farrell A, Allwright S, Toomey D, Bedford D, Conlon K. Hospital admission for acute pancreatitis in the Irish population, 1997 2004: could the increase be due to an increase in alcohol-related pancreatitis? J Public Health (Oxf) 2007;29:398–404. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm069. PMID 17998260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spanier BW, Dijkgraaf MG, Bruno MJ. Trends and forecasts of hospital admissions for acute and chronic pancreatitis in the Netherlands. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20(7):653–8. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f52f83. PMID 18679068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. Trends in the epidemiology of the first attack of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2006;33:323–30. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000236733.31617.52. PMID 17079934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fagenholz PJ, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Harris NS, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA., Jr. Direct medical costs of acute pancreatitis hospitalizations in the United States. Pancreas. 2007;35:302–7. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3180cac24b. PMID 18090234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durbec JP, Sarles H. Multicenter survey of the etiology of pancreatic diseases. Relationship between the relative risk of developing chronic pancreaitis and alcohol, protein and lipid consumption. Digestion. 1978;18:337–50. doi: 10.1159/000198221. PMID 750261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freidreich N. Disease of the Pancreas. In: Ziemssen H, editor. Cyclopoedia of the Practice of Medicine. William Wood; New York: 1878. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gullo L. Alcohol and chronic pancreatitis: leading or secondary etiopathogenetic role? JOP. J Pancreas (Online) 2005;6:68–72. PMID 15650289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dufour MC, Adamson MD. The epidemiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003;27:286–90. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200311000-00002. PMID 14576488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med. 2004;38:613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.027. PMID 15066364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chari ST. Chronic pancreatitis: classification, relationship to acute pancreatitis, and early diagnosis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(Suppl. 17):58–9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1918-7. PMID 17238029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristiansen L, Gronbaek M, Becker U, Tolstrup JS. Risk of pancreatitis according to alcohol drinking habits: a population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:932–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn222. PMID 18779386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1301–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116237. PMID 1626547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orsini N, Bellocco R, Greenland S. Generalized least squares for trend estimation of summarized dose-response data. Stata Journal. 2006;6:40–57. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Royston P, Sauerbrei W. Multivariable model-building: a pragmatic approach to regression analysis based on fractional polynomials for modelling continuous variables. Chichester; John Wiley & Sons; West Sussex, England: Hoboken, NJ: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. PMID 3802833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. PMID 12111919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. PMID 12958120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101. PMID 7786990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. PMID 9310563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stata Corporation . Stata statistical software: release 10.1. Stata Corporation; College Station, TX, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blomgren KB, Sundstrom A, Steineck G, Genell S, Sjostedt S, Wiholm BE. A Swedish case-control network for studies of drug-induced morbidity--acute pancreatitis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58:275–83. doi: 10.1007/s00228-002-0471-4. PMID 12136374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talamini G, Bassi C, Falconi M, Sartori N, Salvia R, Rigo L, et al. Alcohol and smoking as risk factors in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1303–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1026670911955. PMID 10489910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Y, Tamakoshi A, Hayakawa T, Ogawa M, Ohno Y, Research Committee on Intractable Pancreatic Diseases Associations of alcohol drinking and nutrient intake with chronic pancreatitis: findings from a case-control study in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2622–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04121.x. PMID 11569685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morton C, Klatsky AL, Udaltsova N. Smoking, coffee, and pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:731–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04143.x. PMID 15089909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muddana V, Lamb J, Greer JB, Elinoff B, Hawes RH, Cotton PB, et al. Association between calcium sensing receptor gene polymorphisms and chronic pancreatitis in a US population: role of serine protease inhibitor Kazal 1type and alcohol. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4486–91. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4486. PMID 18680227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vonlaufen A, Wilson JS, Pirola RC, Apte MV. Role of alcohol metabolism in chronic pancreatitis. Alcohol Res Health. 2007;30:48–54. PMID 17718401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apte MV, Wilson JS. Alcohol-induced pancreatic injury. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:593–612. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6918(03)00050-7. PMID 12828957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lerch MM, Albrecht E, Ruthenburger M, Mayerle J, Halangk W, Kruger B. Pathophysiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003;27:291–6. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200311000-00003. PMID 14576489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaper AG, Wannamethee G, Walker M. Alcohol and mortality in British men: explaining the U-shaped curve. Lancet. 1988;2:1267–73. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92890-5. PMID 2904004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]