Abstract

Rapidly evolving genetic and genomic technologies for genetic cancer risk assessment (GCRA) are revolutionizing our approach to targeted therapy and cancer screening and prevention, heralding the era of personalized medicine. Although many academic medical centers provide GCRA services, most people receive their medical care in the community setting. Yet, few community clinicians have the knowledge or time needed to adequately select, apply and interpret genetic/genomic tests. This article describes alternative approaches to the delivery of GCRA services, profiling the City of Hope Cancer Screening & Prevention Program Network (CSPPN) academic and community-based health center partnership as a model for the delivery of the highest quality evidence-based GCRA services while promoting research participation in the community setting.

Growth of the CSPPN was enabled by information technology, with videoconferencing for telemedicine and web conferencing for remote participation in interdisciplinary genetics tumor boards. Grant support facilitated the establishment of an underserved minority outreach clinic in the regional County hospital. Innovative clinician education, technology and collaboration are powerful tools to extend GCRA expertise from a NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, enabling diffusion of evidenced-base genetic/genomic information and best practice into the community setting.

Keywords: cancer genetics, community, genetic counseling, genetic education, personalized medicine

Introduction

Rapidly evolving genetic and genomic technologies for genetic cancer risk assessment (GCRA) are revolutionizing our approach to targeted therapy, cancer screening and prevention, heralding the era of personalized medicine. While academic health centers have traditionally led the diffusion of new technologies into community practice, commercial availability and marketing of genetic testing has accelerated the uptake of testing in the community setting, where clinicians are often inadequately prepared to select, apply and interpret genetic tests. Consequently, there are many questions about the composition of the personalized medicine workforce, and challenges related to developing and sustaining best practices in GCRA in the community setting. In this paper we describe some alternate approaches to delivery of high-quality GCRA services that leverage the expertise of the academic health center to promote access and quality care through advanced training and ongoing practice-centered support for community-based clinicians.

Cancer Genetics Overview, Trends and Gaps in State of Knowledge

Although only 5–10% of cancers are known to be associated with highly penetrant hereditary syndromes, thousands of cancer cases are attributable to hereditary predisposition, and the magnitude of risk conferred by these altered genes is dramatic.1 More than 50 cancer-associated syndromes have a genetic basis, and several new cancer-associated genes are reported every year.2 Genetic tools play an increasing role in risk assessment and testing interventions for a broad spectrum of common cancers.3

The GCRA process, which incorporates genetic analysis and empiric risk models to estimate cancer risk and provide personalized, risk-appropriate cancer screening and risk-reduction strategies for individuals and families, requires knowledge of genetics, oncology, and patient and family counseling skills, and involves more provider time than most other clinical services.1, 4

Risk assessment for many highly penetrant cancer predisposition syndromes has clear clinical utility. GCRA increases adherence to surveillance, associated with diagnosis of earlier stage tumors.5 Numerous studies have demonstrated the sensitivity of breast MRI in BRCA positive women.6 Retrospective studies of BRCA carriers indicate that adjuvant tamoxifen7 and risk reduction mastectomy can significantly reduce the risk of new primary breast cancer, up to 50% and 90% respectively.8 Risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomy provides 90% risk reduction for ovarian cancer and may substantially lower breast cancer risk in pre-menopausal women with a BRCA mutation.9, 10 Insights about the role of the BRCA genes in DNA repair have led to the first targeted therapies for BRCA-associated cancers.11 Similarly, strategies for evaluation of hereditary colon cancer risk continues to evolve.12, 13 Importantly, colonoscopic screening is effective in early detection and/or prevention of colon cancer in Lynch syndrome.14

As cancer genetics diagnostic and risk assessment tools move from bench to bedside, there will be a greater demand for broad-spectrum clinical research to further our understanding of how genetic technologies impact the individual, the family, and society at large. Although there is a growing body of research addressing questions about psychosocial outcomes and consequences of genetic testing for cancer risk, much more work is necessary to understand factors affecting quality of life in order to develop appropriate interventions and decision aides. Health services research is also needed to investigate the problems and limitations of delivering cancer genetics services to the larger community, including underserved populations.

Research on cost-effective mechanisms to transfer state-of-the-art cancer genetics technology into clinical practice are needed to enhance cancer prevention and control efforts in the community.15 This challenge is particularly acute for the emerging field of genomics and personalized medicine.16 Recent discoveries from genome wide association studies (GWAS) of low-penetrance genetic variants with modest associated risk are changing the paradigm of how genetic information is delivered (Figure 1) and challenging clinicians to keep abreast of these advances.17, 18 Commercial laboratories are capitalizing on GWAS by offering genome scans for single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with disease risk and translating that risk into absolute risk estimates through the use of various algorithms. However, little is known about whether these algorithms are well calibrated or whether the risk estimates provided by genome scans are accurate. A recent small study comparing two direct-to-consumer companies found differences in relative risk predictions for cancer, heart disease, diabetes and other conditions for the same set of individuals, attributed in part to discrepancies in markers used to calculate relative risk and risk determination methods.19 Further, these genomic profiles are of uncertain clinical utility, as the reported risk is generally too small to form an appropriate basis for clinical decision-making.20 The recently revised American Society of Clinical Oncologists (ASCO) Policy Statement on genetic and genomic testing highlights the difficulties in assigning clinical utility and potential hazards of non-professionally mediated genetic analyses.21

Figure 1. Clinical Utility of Genetic and Genomic Testing.

Legend included in figure.

Transition from the Multidisciplinary Academic Health Center Model to Community-based GCRA

The earliest GCRA delivery models emerged from the academic health center setting, where GCRA is conducted through one or more consultative session with an interdisciplinary team that may include genetic counselors, advanced practice nurses, one or more physician (generally a medical geneticist or oncologist), and a mental health professional.22 Although several academic health centers across the nation provide comprehensive GCRA services, most people receive their medical care in the community setting. Unfortunately, few community-based medical centers are equipped to deliver this service model, due to a lack of adequately trained personnel and an unfavorable reimbursement climate for counseling-dominated care.23–25

Various practice models are evolving to meet the growing demand for GCRA services in the community setting (Table 1).25–27 Some of these models combine efficient patient care with best practices in GCRA. Others may not adequately address important nuances inherent in the GCRA process that inform several aspects of patient care, including optimal testing strategies, appropriate interpretation of uninformative test results, consideration of alternate genetic etiologies, psychosocial and family communication dynamics, and other factors.

Table 1.

Models of Practice for GCRA

| Model | Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Model | ||

| Academic/medical center model: Patients referred to cancer genetics program, seen by interdisciplinary team (genetic counselor, nurse, physician). Pre- and post-genetic testing counseling and integrated risk assessment (COH1 comprehensive model) | • Comprehensive state-of-the-art personalized GCRA delivery including genetics-focused physical exam and medical management • level of care expected of a cancer center setting; billable patient visits • critical research linkage |

• Through-put may be limited by physician availability, personnel costs and time intensity of providing comprehensive GCRA service • possible community clinician barriers to referral |

| Community Models | ||

| Community center partners with academic center of excellence | • Advanced practice-based support from the academic center for community center clinicians. • Patients receive high level care • Access to the academic center clinical and research data forms and genetics research |

• Possible fees for academic oversight • Time commitment for quality assurance activities |

| Oncologist or other physician initiates genetic testing; only refers patients with positive or ambiguous results to genetics provider | • Immediate offering of genetic test may be effective means of GCRA delivery for carefully selected patients • Complicated cases referred to genetics provider for thorough counseling and risk assessment |

• Nuances of GCRA underestimated; possible errant test/testing approach; patient and family may be falsely reassured • patient may not be given sufficient information to make informed decision for genetic testing/testing strategies |

| Patient referred to cancer risk counselor (GC2/APN3) for genetic counseling/testing, summary note sent to referring physician | • Meaningful counseling and risk assessment service provided by qualified personnel | • Patient given general vs. tailored risk reduction recommendations • No or limited billable GCRA service no or limited physical exam to help guide assessment • Cancer genetics research participation limited |

| Triage model: APN performs initial personal/family history screening; triages to GC for further assessment; referring physician provides patient-recommendations | • Streamlined referral process • Patients requiring individual counseling identified and seen in a timely manner • Efficient use of limited genetics provider resources |

• APN/GC may not have adequate cancer genetics knowledge to triage/assess appropriately • Referring physician may not be familiar with current risk level-based medical management • Cancer genetics research participation limited |

| Group model: at-risk individuals attend a group-focused cancer genetics presentation, followed by individual counseling sessions as indicated based on risk and/or as desired by patient | • Efficient for providing overview of GCRA and pre-screening referred patients • Efficient use of limited genetics provider resources |

• Ineffective for anxious patients, particularly if recent cancer diagnosis • Time constraints to address individual questions • Group session not a billable service • Patient confidentially/privacy may be compromised |

| Telemedicine: Community center servicing a geographically or socioeconomically underserved population partnered with an academic center of excellence | • Patients gain access to academic center -level of clinical care, including opportunities for research participation • Efficient use of limited genetics provider resources |

• Requires telemedicine set up and time commitment for quality assurance • consultation services may not be billable • may require funding to establish partnership |

| Remote open access model: Educational materials and phone and/or internet counseling provided by for-profit company | • Counseling may be scheduled at the convenience of the patient (possibly from home) • May be cost savings |

• Little quality outcomes data • Possible lack of local clinician communication or follow up • No research opportunities |

City of Hope (COH)

Genetic counselor (GC)

Advanced practice nurse (APN)

The City of Hope Model for Extending Cancer Genetics Expertise to the Community

The City of Hope Division of Clinical Cancer Genetics was established in 1996 to be a national leader in the advancement of cancer genetics, screening and prevention, through innovative patient care, research and education. The Division includes the Cancer Screening & Prevention Program Network (CSPPN) for full-spectrum GCRA services, and the Cancer Genetics Education Program (CGEP), developed to educate medical professionals about the emerging science and clinical utility of cancer genetics (Figure 2). The CSPPN and CGEP facilitate the integration of genetics services in the community and provide access to a robust program of laboratory and health services research via an IRB-approved Hereditary Cancer Registry prospective study protocol.22, 28

Figure 2.

The Program incorporates the robust clinical research resources of the City of Hope Department Cancer Screening and Prevention Program, and the multifaceted training expertise Cancer Genetics Education Program (CGEP), initiated in 1997 with guidance and expertise from the COH Dept of Nursing Education. The Cancer Genetics Career Development Program maximizes the resources and expertise of the CGEP for cancer genetics Program Leadership training. The program offers multi-institutional academic and research mentorship resources through collaborations with the City of Hope Beckman Research Institute and the Department of Preventive Medicine at University of Southern California. The community clinician education component is detailed in the text. Feedback from patients as stakeholders is accomplished via a series of conferences, with mixed methods collection of data. An advisory committee to the CGEP is comprised of key faculty in Nursing Research and Education, the Beckman Research Institute, and intra-and extramural professionals from the fields of education, law, bioethics, molecular genetics and preventive medicine, as well as community-based advocates.

Initiated in 1996, the Registry has accrued more than 6,000 participants with 4-generation family histories and blood/DNA samples, with associated psycho-social and clinical follow-up data (e.g., screening and risk reduction behavior, risk communication). The consent document and process is explicit about sharing anonymized biospecimens with other investigators. The Registry has facilitated scholarly research created in collaboration with community partners in the realms of genetic epidemiology, bio-behavioral, disparities and health services research. Data from the Registry enable participation in the multi-institutional consortia that are necessary to assemble enough hereditary cases for epidemiological studies. Further, locally-relevant and practical health services research enabled by the registry has influenced clinical practice guidelines.29, 30

Cancer Screening & Prevention Program Network (CSPPN)

As a major component of NCI-Comprehensive Cancer Center status, the CSPPN serves as a resource to community medical centers and clinicians who generally would not have the infrastructure and expertise necessary to develop this model of care. A detailed description of the establishment of the CSPPN and our hub-and-spoke community outreach program have been previously described.22 In brief, community-based centers are contracted with the City of Hope for program development, training in GCRA for personnel, and continuing practice-centered support to promote quality care. The program development activities are tailored to address the needs and resources of each community center. A site assessment may also be conducted by the COH team to identify appropriate physical space for the GCRA sessions, preferably within or adjacent to the community center's medical and/or surgical oncology services. In addition to a thorough orientation to the City of Hope GCRA protocols, advice and assistance is provided regarding clinic and family history instruments, selection of pedigree database software.

Different Models for Different Settings

To date the CSPPN has provided comprehensive GCRA services to more than 6,000 individuals and their families, with approximately 20% of these stemming from the satellite clinics. In our Cancer Center of Santa Barbara (CCSB) and St. Jude Medical Center (SJMC), Virginia Crossen Cancer Center affiliates, an advanced practice nurse (APN) credentialed in genetics initiates risk assessment and enrollment in our Hereditary Cancer Registry. Patients are then seen by a CSPPN physician and the APN at a subsequent visit; the physician uses evaluation and management codes to bill for visits.

At Good Samaritan Medical Center in Arizona, an APN with board certification in genetic counseling provides cancer risk counseling and administers the program with clerical support and oversight by a local oncologist, and case-based guidance from the CCG Working Group (described below). Another genetic counselor was recently brought on-board to help with increasing referrals. Both counselors see patients independently and generate a patient visit note to the referring physician.

Similarly, with CSPPN support services, St. Joseph's Medical Center in Orange County, CA hired a board-certified genetic counselor who completed an advanced one-year traineeship in cancer genetics at the City of Hope to lead their GCRA program. With institutional and multidisciplinary support for the program from a medical oncologist, surgical oncologist, and a colorectal surgeon, two additional genetic counselors have been hired to meet the increasing referral base. Development of the GCRA program, as well as accrual to the Registry and related research, contributed to successful competition for an NCI community cancer center planning grant.

Additional CSPPN affiliated programs have been developed for underserved and minority communities. The best example is a project to deliver culturally competent GCRA at the Los Angeles County Olive View Medical Center, which serves a predominantly Hispanic community in Southern California. A key element of the program's success is genetic counseling provided by bilingual cancer risk counselors trained in culturally sensitive approaches to GCRA.31 A critical component deemed necessary prior to program implementation was a commitment from the referring institution to provide risk-appropriate cancer screening and prevention for referred patients and an on-site bilingual patient coordinator to facilitate the process. The project success yielded a grant (Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation Grant # POP0600464) to examine an emerging social-cognitive theoretical model regarding perceived access to care and post-GCRA behaviors in this population.32

In addition, a recently established tele-health initiative (videoconference-mediated GCRA) between City of Hope and Toiyabe Indian Health Project (Indian Health Service) in Bishop California is another example of addressing the community need (the nearest genetic counseling program is at least 4 hours drive), while addressing disparities and enhancing related health services research. Alternative modes of GCRA delivery may enable cost-effective community medical center participation. The choice of models is dependent in part on the availability of qualified staff and the local institutional economic environment. Billing for mid-level services is sometimes possible via facility fee or individual provider codes. Apprising administrators of potential downstream revenue from cancer screening, chemoprevention, and surgical risk reduction interventions may help them justify under-reimbursed program costs.33–35

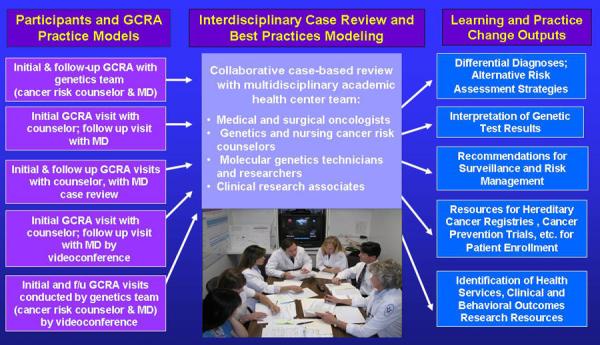

Quality Assurance in GCRA: Clinical Cancer Genetics (CCG) Working Group and Topics in Cancer Genetics Research

CSPPN affiliates have ongoing access to the evidence-based updates and practice-centered support essential to sustaining an informed community-based GCRA practice through participation in two CME-accredited web conference activities: Clinical Cancer Genetics (CCG) Working Group and Topics in Clinical Cancer Genetic Research. CCG Working Group (Figure 3) is an interdisciplinary cancer genetics case conference series conducted each week by the City of Hope clinical team. CSPPN and affiliated clinicians across the U.S. present cases from their community practices via Microsoft Live™ web conference interface for discussion and recommendations on risk assessment, surveillance, risk management and identification of research eligibility for cases covering the full spectrum of hereditary cancer. Table 2 is a summary sampling of types of recommendations for community-based cases generated during CCG Working Group over a 17-week period.

Figure 3. Clinical Cancer Genetics (CCG) Working Group.

Legend included in figure.

Table 2.

Recommendations for Cases Presented by Community-based Clinicians Generated During CCG1 Working Group web conferences: A Snapshot of Multidisciplinary Quality Control

| Nature of Working Group Advice: | Frequency of Advice |

|---|---|

| Change in diagnostic strategies | 7 |

| Identify testing candidates | 42 |

| Interpret test results | 26 |

| Provide risk assessment | 42 |

| Recommend management and f/u | 50 |

| Confirm testing strategy | 49 |

| Determine if appropriate for rearrangement test | 8 |

| Expand differential diagnoses | 27 |

| Recognize secondary genetic pattern in family | 11 |

| Interpret pathology report | 17 |

| Consensus regarding phenotype | 11 |

| Interpret VUS results | 6 |

| Calculate mutation probability | 7 |

| Suggestions for research protocol eligibility | 16 |

| Other2 | 22 |

| Cases advised over 17 weeks | 248 |

Clinical Cancer Genetics (CCG)

Other categories include family communication solutions, empiric risk management advice, requesting pathology report, insurance issues, and counseling strategies.

Topics in Clinical Cancer Genetics is a weekly one-hour web-conference seminar series focused on timely issues in clinical cancer genetics, cancer epidemiology and cancer genetics research, alternating between didactic lectures, case-based literature reviews, and basic research journal club. City of Hope faculty, guest lecturers from other academic institutions, CSPPN affiliates and alumni of the City of Hope Intensive Course in Clinical Cancer Genetics (described below) are included in the roster of presenters to ensure that the topics covered address the practice-centered learning needs of the community-based participants.

Expanding the Expertise and Support of the Academic Health Center: The Intensive Course in Community Cancer Genetics and Research Training

Interdisciplinary GCRA training and CME activities are essential to extend the expertise and resources of the academic health center to the community-based setting. Oncology, genetics, nursing and government health organizations (including ASCO, NIH, ASHG, NSGC, ONS and ISONG) and academic institutions offer cancer genetics seminars, workshops and web-based resources, and the ASCO Task Force on Cancer Genetics Education produced a Cancer Genetics & Cancer Predisposition Testing Curriculum for oncologists and other health care providers that was originally published in 1998 and updated in 200436, 37.

In response to the national need for specialized training in cancer risk assessment, the City of Hope conducts an NCI-funded (R25E CA #112486) Intensive Course in Community Cancer Genetics and Research Training for community-based genetics and oncology practitioners38. The goal of the course is to increase the number of clinicians across the nation with practitioner-level competence in GCRA through a combined program of CME-accredited distance-learning didactics, face-to-face training and post-course professional development activities. A number of the CSPPN affiliate clinicians established their formal collaborations with the City of Hope as a consequence of their participation in the course. As depicted in Figure 4, 140 clinicians representing community-based clinical practices in 41 U.S. states, as well as Canada, Brazil, Chile and Spain, completed the course as of December, 2009. Upon completion of on-campus training, all course participants are invited to join the roster of CSPPN affiliates and intensive course alumni who participate in Topics in Clinical Cancer Genetic Research (TICGR) and CCG Working Group for ongoing professional development and case-based support upon return to their practice settings.

Figure 4.

Legend included in figure.

Technical Support for the CSPPN

The distance-mediated networking that sustains the CSPPN is enabled by information technology, with videoconferencing for telemedicine and web conferencing for remote participation in the CCG Working Group, Topics in Cancer Genetics Research and the distance-mediated learning and professional development activities of the Intensive Course. The Enterprise (multi-client server) version of Progeny™ (Progeny Software LLC, South Bend, IN), pedigree-drawing software was obtained and customized to the clinical and research needs of the CSPPN. Each satellite purchased their own pedigree software license and the City of Hope database framework with customized fields was distributed to each satellite program. Sending out updated versions of the database framework is critical to seamless compatibility, both for pedigree presentation at the working group and for research data sharing. In addition to technical support from the software company, two super users at the Cancer Center provide assistance with clinical research issues related to the database and interactions with the Cancer Center master database. Scannable forms were developed for clinic and family history questionnaires for use in the CSPPN, including forms for efficient data entry for the Registry study.

Summary

Once delivered primarily through academic health centers, a number of alternative delivery models have evolved to extend GCRA services beyond the confines of the academic healthcare delivery system to the broader community.21, 22 (add other refs included above -- Wham, Cohen, Allain) Provision of GCRA is an important growing service for community-based clinicians. In part due to very limited access to GCRA services there has been a paucity of health services and psychosocial research on the underserved, underinsured, and many ethnic minorities. Measures to increase access and cost-effectiveness are particularly important given limited available resources to address disparities.3 Recent outcomes from our research program indicate that providing GCRA to underserved Latinas at the Los Angeles County Olive View Medical Center is accepted in the community and prompts increased risk appropriate follow up care, despite relatively low acculturation.32, 39

The rapid evolution of genetic information and direct-to-consumer and to-physician marketing by commercial genetic testing vendors are prompting a steady increase in the number and spectrum of clinicians who provide GCRA services in the community setting.23, 24, 40 Despite the push toward non-professionally mediated genetic and genomic testing, ASCO and other leading oncology and genetics professional organizations continue to recommend that pre- and post-test counseling be conducted by clinicians with the necessary skills and experience.17, 30, 41–43 This paper describes the benefits and limitations of several delivery models, with a focus on the important role comprehensive cancer centers can take to promote and support high quality GCRA in their communities. No matter what models are employed to address the demand for more efficient and broader coverage of GCRA services, no model should compromise informed decision making by patients. Considering the overwhelming interest in City of Hope cancer genetics education programs from busy clinicians from across the US, it is clear that quality is still important. A growing number of course alumni continue to participate in the CCG Community of Practice. As the legislative effort to reform healthcare proceeds it is critical that provisions are included to address current problems related to inadequate coverage for preventive care given evidence of cost-effectiveness and benefits of GCRA from the societal perspective.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research and education programs described in this manuscript were supported by several sources of funding: Cancer Genetics Education Program supported in part by National Cancer Institute Grants 2R25 CA75131, R25 CA112486, and R25 CA85771, and by Project # MCHG-51 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services; Underserved outreach programs were supported in part by California Cancer Research Program Grant Number 00-92133, and by project # POP0600464 from Susan G. Komen for the Cure; the Registry and The City of Hope Center for Cancer Genetics Technology Transfer Research was supported in part by the California Cancer Research Program, Grant No. 99-86874, and by a General Clinical Research Center grant from NIH (M01 RR00043) awarded to the City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, California. We also wish to thank all the community colleagues and administrators who played important roles in the development of the Network sites, including: Frederick Kass, MD, Clarence Petrie, MD, Susan Dimpfel, RN, MSN, Ian Grady, MD, Anita Gregory, MD, David King, MD (In Memoriam), Kimberly Banks, MS, CGC, David Margileth, MD, and Joan Taylor, MBA, Patty Dock, MS, CGC, Jane Congleton, RN, MS, CGC, Nancy Feldman, MD, Lori Viveros, MPH, CHES.

References

- 1.Weitzel JN. Genetic cancer risk assessment: Putting it all together. Cancer. 1999 Dec 1;86(11 Suppl):2483–2492. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991201)86:11+<2483::aid-cncr5>3.3.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lippman SM, Hawk ET. Cancer prevention: from 1727 to milestones of the past 100 years. Cancer Res. 2009 Jul 1;69(13):5269–5284. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Cancer-related genetic testing and counseling: Workshop proceedings. Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeMarco TA, Smith KL, Nusbaum RH, Peshkin BN, Schwartz MD, Isaacs C. Practical aspects of delivering hereditary cancer risk counseling. Semin Oncol. 2007 Oct;34(5):369–378. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halbert CH, Lynch H, Lynch J, et al. Colon cancer screening practices following genetic testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) mutations. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Sep 27;164(17):1881–1887. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.17.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warner E, Messersmith H, Causer P, Eisen A, Shumak R, Plewes D. Systematic review: using magnetic resonance imaging to screen women at high risk for breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2008 May 6;148(9):671–679. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-9-200805060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narod SA, Brunet JS, Ghadirian P, et al. Tamoxifen and risk of contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: A case-control study. Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Lancet. 2000 Dec 2;356:1876–1881. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Lynch HT, et al. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE study group. J Clin Oncol. 2004 March 15;22(6):1055–1062. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finch A, Beiner M, Lubinski J, et al. Salpingo-oophorectomy and the Risk of Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Peritoneal Cancers in Women With a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation. JAMA. 2006 July 12;296(2):185–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.185. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rebbeck TR, Kauff ND, Domchek SM. Meta-analysis of risk reduction estimates associated with risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009 Jan 21;101(2):80–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase in Tumors from BRCA Mutation Carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 24;361(2):1–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch HT, Casey MJ, Snyder CL, et al. Hereditary ovarian carcinoma: heterogeneity, molecular genetics, pathology, and management. Mol Oncol. 2009 Apr;3(2):97–137. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular Basis of Colorectal Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009 December 17;361(25):2449–2460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarvinen HJ, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Aktan-Collan K, Peltomaki P, Aaltonen LA, Mecklin JP. Ten years after mutation testing for Lynch syndrome: cancer incidence and outcome in mutation-positive and mutation-negative family members. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Oct 1;27(28):4793–4797. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flowers CR, Veenstra D. The role of cost-effectiveness analysis in the era of pharmacogenomics. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(8):481–493. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Q, Flanders WD, Moonesinghe R, Ioannidis JP, Guessous I, Khoury MJ. Using Lifetime Risk Estimates in Personal Genomic Profiles: Estimation of Uncertainty. Am J Hum Genet. 2009 Nov 18; doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robson M, Storm C, Weitzel JN, Wollins D, Offit K. American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement Update: Genetic and Genomic Testing for Cancer Susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans JP. Health care in the age of genetic medicine. JAMA. 2007 December 12;298(22):2670–2672. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2670. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng PC, Murray SS, Levy S, Venter JC. An agenda for personalized medicine. Nature. 2009 Oct 8;461(7265):724–726. doi: 10.1038/461724a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke W, Psaty BM. Personalized medicine in the era of genomics. JAMA. 2007 Oct 10;298(14):1682–1684. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ali M, Telfer BA, McCrudden C, et al. Vasoactivity of AG014699, a clinically active small molecule inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase: a contributory factor to chemopotentiation in vivo? Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Oct 1;15(19):6106–6112. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDonald DJ, Sand S, Kass FC, et al. The power of partnership: Extending comprehensive cancer center expertise in clinical cancer genetics to breast care in community centers. Seminars in Breast Disease. 2006;9:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zon RT, Goss E, Vogel VG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement: The Role of the Oncologist in Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Dec 15; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geier LJ, Mulvey TM, Weitzel JN. ASCO 2009 Educational Book: Practice Management and Information Technology. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2009. Clinical cancer genetics remains a specialized area: How do I get there from here? [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wham D, Vu T, Chan-Smutko G, Kobelka C, Urbauer D, Heald B. Assessment of clinical practices among cancer genetic counselors. Fam Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen SA, McIlvried D, Schnieders J. A collaborative approach to genetic testing: a community hospital's experience. J Genet Couns. 2009 Dec;18(6):530–533. doi: 10.1007/s10897-009-9243-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allain D, Baker M, Blazer K, et al. Evolving Models of Cancer Risk Genetic Counseling. Perspectives in Genetic Counseling. 2009 Winter;31(4) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blazer KR, Grant M, Sand SR, et al. Development of a cancer genetics education program for clinicians. J Cancer Educ. 2002 Summer;17:69–73. doi: 10.1080/08858190209528801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weitzel J, Hendrickson B, Lagos V, et al. Identification of a Novel Frequent Large Genomic Rearrangement of BRCA1 in High-risk Hispanic Families. Paper presented at: The American Society of Human Genetics; Salt Lake City, Utah. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.NCCN Genetic/ Familial High-risk assessment: Breast and Ovarian. [Accessed 15 June, 2009];Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. [2009 April 6; V.I. 2009: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

- 31.Ricker C, Lagos V, Feldman N, et al. If we build it … will they come? - Establishing a cancer genetics services clinic for an underserved predominantly Latina cohort. J Genet Couns. 2006 Dec;15(6):505–514. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lagos VI, Perez MA, Ricker CN, et al. Social cognitive aspects of underserved Latinas preparing to undergo genetic risk assessment for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2008 July 22;17(8):774–782. doi: 10.1002/pon.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho C. How to develop and implement a cancer genetics risk assessment program: Clinical and economic considerations. Oncology Issues. 2004;19(November/December):22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pirzadeh S. Starting a Cancer Genetics Clinic in a County Hospital. Oncology Issues. 2009 November/December;24(9):38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacDonald DJ. Establishing a Cancer Genetics Service. In: Kuerer H, editor. Kuerer's Breast Surgical Oncology. First ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 36.ASCO . Cancer Genetics & Cancer Predisposition Testing. ASCO Curriculum. Vol 1 & 2. American Society of Clinical Oncology; Alexandria, VA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37.ASCO . Cancer genetics & cancer predisposition testing. ASCO; Alexandria, VA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blazer K, MacDonald D, Nedelcu R, Sand S, Weitzel J. Design and Outcomes of an Intensive Course in Cancer Risk Assessment for Genetic Counselors and Advanced-Practice Nurses. Paper presented at: National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC).2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagos VI, Blazer KR, Viveros L, et al. National Latino Cancer Summit. San Francisco, CA: 2008. Impact of genetic cancer risk assessment on cancer screening and prevention behaviors in an underserved predominantly Latina population [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 40.ACOG ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 103: Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):957–966. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a106d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ONS Cancer Predisposition Genetic Testing and Risk Assessment Counseling. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trepanier A, Ahrens M, McKinnon W, et al. Genetic Cancer Risk Assessment and Counseling: Recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. 2004 April;13(2):83–114. doi: 10.1023/B:JOGC.0000018821.48330.77. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.NCCN The NCCN colorectal cancer screening clinical practice guidelines in oncology. JNCCN. 2003;1:72–93. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]