Abstract

Upregulation of the matrix metalloproteinase MMP-9 plays a central role in tumor progression and metastasis by stimulating cell migration, tumor invasion and angiogenesis. To gain insights into MMP-9 expression, we investigated its epigenetic control in a reversible model of cancer that is initiated by infection with intracellular Theileria parasites. Gene induction by parasite infection was associated with tri-methylation of histone H3K4 (H3K4me3) at the MMP-9 promoter. Notably, we found that the H3K4 methyltransferase SMYD3 was the only histone methyltransferase upregulated upon infection. SMYD3 is overexpressed in many types of cancer cells, but its contributions to malignant pathophysiology are unclear. We found that overexpression of SMYD3 was sufficient to induce MMP-9 expression in transformed leukocytes and fibrosarcoma cells, and that pro-inflammatory phorbol esters further enhanced this effect. Further, SMYD3 was sufficient to increase cell migration associated with MMP-9 expression. In contrast, RNAi-mediated knockdown of SMYD3 decreased H3K4me3 modification of the MMP-9 promoter, reduced MMP-9 expression and reduced tumor cell proliferation. Furthermore, SMYD3 knockdown also reduced cellular invasion in a zebrafish xenograft model of cancer. Together, our results define SMYD3 as an important new regulator of MMP-9 transcription, and they provide a molecular link between SMYD3 overexpression and metastatic cancer progression.

Keywords: epigenetic, metastasis, chromatin, SMYD3, MMP-9

INTRODUCTION

Cancer progression is a multi-step process resulting from altered gene expression through genetic and epigenetic mechanisms (1, 2). As epigenetic events might be reversed using targeted therapies, there is intensive effort to understand the interplay between these mechanisms in the transcriptional control of key regulatory molecules and the altered epigenetic landscape of cancer cells (2). To investigate epigenetic events in cancer progression, we studied a transformation model offering several unique experimental features. Infection by intracellular Theileria parasites causes a lymphoproliferative disease in cows with clinical features similar to some human leukemia. T. annulata infects mainly B cells and macrophages, whereas T. parva infects B and T lymphocytes (3, 4). Theileria-infected cells are transformed and immortalized; displaying uncontrolled proliferation independent of exogenous growth factors in vitro and increased ability to migrate and form metastases in immunodeficient mice (5, 6, 7). Interestingly, Theileria-dependent transformation is reversible; animals treated with the theilericidal drug Buparvaquone are cured in most cases (3, 8, 9). When Theileria-infected cells are treated in vitro with Buparvaquone, the intracellular parasite disappears from the host leukocyte, which either enters apoptosis or stops proliferating, regaining growth factor-dependence (8). Studies showed that Theileria alters host signal transduction pathways, but there is no evidence of permanent host genome changes (4). Theileria infection activates the JNK pathway and the AP-1 transcription factor (10, 11), which are critical for both the survival and invasiveness of transformed B lymphocytes (5). Theileria also induces the IKK pathway leading to NF-κB activation (12) and the TGF-β pathway implicated in virulence (6). This system offers a unique model to address reversible, epigenetic changes involved in tumorigenesis.

Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) proteins may function as mediators of metastasis of Theileria-infected cells (13-15). The large family of MMP proteases play critical functions in development and cancer progression (16). In particular, MMP-9 plays an important role in tumorigenesis and metastasis formation by regulating tumor growth, angiogenesis, cell migration and invasion (16). MMP-9 is a collagenase that degrades Extracellular Matrix (ECM) components including collagens and laminin. Its role in cancer progression is related to ECM degradation and growth factor release (17). The MMP-9 gene is mainly regulated at the transcriptional level by trans-activators binding to the promoter, including AP-1 and NF-κB (18, 19). Recent studies provided insights into how MMP-9 expression is regulated in different cancer types and the role of chromatin modifications (20). MMP-9 transcription involves a stepwise, coordinated recruitment of activators, chromatin modifiers, co-activators and general transcription factors to its promoter (21, 22).

Although MMP-9 was linked to the invasive phenotype of Theileria-transformed cells (13-15), the involvement of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms (and their reversibility) has never been explored in Theileria-infected leukocytes. We studied MMP-9 expression in Theileria-infected cells as a model for epigenetic regulation in leukocyte transformation. The invasive B-cell lymphosarcoma cell line TBL3 was generated by in vitro infection, with T. annulata, of immortalized BL3, a bovine B sarcoma cell line (23). TBL3 cells have a higher invasive capacity than BL3 cells and elevated MMP-9 expression (15). Here, we show that Theileria infection induces the reversible expression of the histone methyltransferase SMYD3 (SET and MYND-domain containing 3). SMYD3 encodes a histone H3K4 di- and tri-methyltransferase involved in tumor proliferation in colorectal, hepatocellular and breast carcinomas (24, 25). SMYD3 binds specific DNA sequences, 5′-CCCTCC-3′ or 5′-GGAGGG-3′, in the promoter region of target genes, leading to transcriptional activation (24). However, the role of SMYD3 in cancer progression is unclear and few direct target genes are known. We show that SMYD3 protein binds to the MMP-9 promoter and regulates expression in Theileria-infected cells and human tumor models. Moreover, SMYD3 knockdown led to decreased H3K4me3 marks on the MMP-9 promoter and reduced MMP-9. Interestingly, SMYD3 levels impact the transformed phenotypes and tumor invasiveness. Thus, our work identifies SMYD3 as a novel regulator of the MMP-9 metastatic gene affecting tumor migration and invasion in vitro and in vivo, thereby highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target to treat metastatic disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents

Parental BL3 and infected TBL3 cells, previously described (23), were cultured at 37°C in RPMI1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 2mM L-Glutamine, 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS), 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin, 10mM Hepes and 50mM 2-mercaptoethanol. HT1080-2.2 cells (with an integrated 2.2 Kb MMP9 promoter-Luciferase) obtained from Dr. C Yan (Albany Medical College, USA) (26) were cultured at 37°C in DMEM with Glutamax and high glucose, supplemented with antibiotics and 10% FCS. Cells were treated with Buparvaquone (BW720c) (Calbiochem) at 50 ng/ml for 64 hours or with Phorbol-12 Myristate 13-Acetate 9 (PMA) (Sigma p1585) 50 ng/ml for 8 hours. Composition of all buffers are detailed in Supplementary material.

Viability assays

1×104 cells were plated in 96-well plates in triplicate and Buparvaquone was added at different concentrations. After 48 hours, cell viability was measured using the Cell proliferation Kit II–XTT (Roche) and the GloMax®-Multi Detection System (Promega).

Invasion assays

Bovine TBL3 and BL3 cells (5×104) were incubated with/without Buparvaquone, resuspended in 1% FCS and seeded onto Matrigel™ (BD Biosciences) (70 μl) in Boyden chamber, BD Falcon™ Cell Culture Inserts (8 μm pores, BD Biosciences). Lower chambers contained 20% FCS medium as a chemoattractant. After 24 hours at 37°C, migrated cells were stained with crystal violet and counted under the microscope (40x objective, at least 10 fields per filter). To test migration of human HEK293 or HT1080 cells, cells were trypsinized and placed in the upper chamber (1×104 cells) coated with 10 μg/ml collagen I in media containing 0.3% FCS and 20% FCS in the lower chamber. After 16 hrs, cells were fixed with 4% formaldhehyde and migrated cells were stained and counted. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Migration index is the number of migrated cells per filter (Control set to 1).

Soft agar assay

Cells were suspended in 0.35% agarose containing 10% FCS and plated above 0.5% agarose at 1×104 cells per 6-well plate. After 10-14 days, colonies were stained with crystal violet and scored. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Plus Mini Kit® (Qiagen). cDNA synthesis was performed with RT Superscript III (Invitrogen) and semiquantitative PCR analysis with goTaq polymerase (Promega). Quantitative PCR amplification was performed in the ABI7500 machine (Applied Biosystems) using Sybr Green (Applied Biosystems). See Table S1 for primer sequences. Relative quantities of mRNA were calculated using the deltaCt method.

Western blot

Proteins were extracted with Laemmli lysis buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, before incubation overnight at 4°C with antibodies against MMP-9, SMYD3 or β-Actin, (see Supplementary data) followed by secondary antibodies. Membranes were developed using SuperSignal® (Thermo Scientific).

Zymography

Supernatants from cells grown in serum-free media were mixed with lysis buffer and loaded into SDS-Polyacrylamide gels, co-polymerized with 0.1% gelatin. Gels were washed twice (30 minutes in renaturing buffer (2.5% Triton X-100) and incubated at 37°C, 18 hours in a Gelatinase solution. Gels were stained with 0.5% Coomasie Blue and de-stained with Methanol:Acetic Acid (50:10).

Transfection

HT1080 and HEK293T (human embryonic kidney transformed with the AgT) cells were transfected with Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen). The pGL3-Nkx2.8–WT-SBE and pcDNA-SMYD3 vectors were obtained from Dr. Y Furukawa (Tokyo University, Japan) (24). The MMP9 promoter-Luciferase construct was obtained from Dr. D Boyd (MD Anderson Cancer Center, USA).

Luciferase Assays

Dual luciferase assays (Promega) were performed using the GloMax®-Multi Detection System (Promega) to measure Firefly and Renilla Luciferase activity. The pGL4 hRluc/TK Vector was used for luciferase assay normalization.

Gene silencing

For short-term depletion experiments, cells were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides (60nM) Table S1. The shRNA vector targeting human/bovine SMYD3 was constructed by cloning double-stranded oligonucleotides into the pSuper-vector (Oligoengine), generating siRNA directed against the sequence AGCCTGATTGAAGATTTGA. shCtrl plasmid is an empty pSuper-vector.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Chromatin was extracted from 5-20 ×106 cells and crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde (10 min, 37°C). After incubation in cell lysis buffer 30 minutes at 4°C, nuclei were resuspended in nuclei lysis buffer containing glass beads (400 μl per ml) (Sigma) before sonication (4-5 cycles of 4 minutes) using the Biorupter (Diagenode). The INPUT sample (5%) was removed before the IP. Chromatin aliquots (20μg or 50μg for transcription factors) were immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies overnight at 4°C and recovered with pre-blocked Protein G/A sepharose beads (Sigma). Washes were as following: twice TSE-150mM NaCl buffer, once TSE-500mM NaCl buffer, once washing buffer and twice TE buffer. Beads were diluted in 100 μl of dilution buffer plus 150 μl de TE/1% SDS. After de-crosslinking, DNA was analyzed by qPCR. The immunoprecipitation enrichment was calculated using the deltaCt method. Results were presented as “percentage of enrichment” of INPUT sample (100x [Output/Input]) or as “fold-enrichment” (100x [Output/Input] normalized to binding on MMP-9 promoter in Control cells).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were fixed in 70% ethanol and washed twice in PBS, incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes in PI buffer (50 μg/ml propidium iodide; Sigma) containing 100 μg/ml RNaseA. Cells were analyzed using the Facscalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), with data acquisition using CellQuest software.

Animal care and xenografts

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) (wild-type AB strain, and casper, generously given by Amagen Paris) were handled according to the European Union guidelines. Fish were kept at 28°C in aquaria with day/night light cycles. HT1080 cells were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides. After 24 hrs, cells were incubated with D-PBS containing 10 μM fluorescent Cell tracker Green CMFDA (Invitrogen). 20-30 cells were injected into the yolk of dechorionated and anesthetized (Tricaine methanesulfonate) 48 hpf (hours post fertilization) embryos using a Femtojet microinjector (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Embryos were incubated at 34°C for 3 days and analyzed using a microscope Station cell observer ZEISS and Axio Vision software.

RESULTS

Theileria infection induces MMP9 expression and increased invasiveness

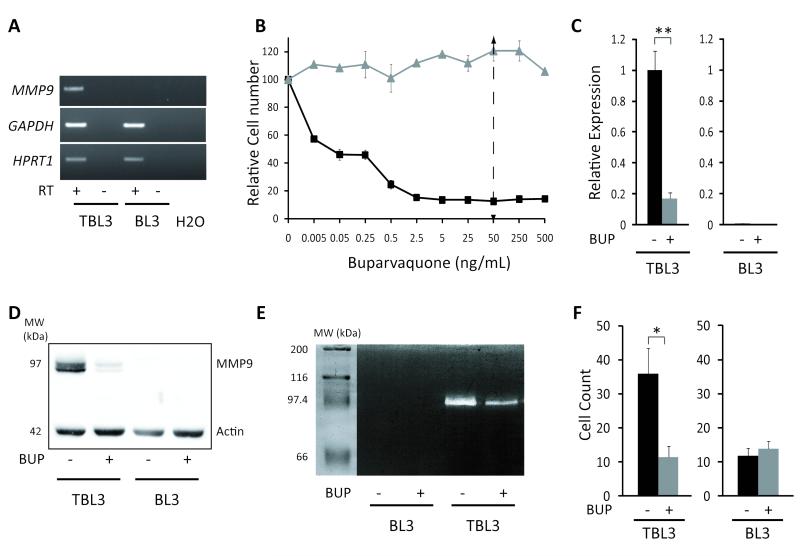

As MMP-9 expression has been linked to Theileria-transformation (7, 15, 27), we analyzed mRNA and protein in Theileria-infected TBL3 cells and the non-infected BL3 parental cell line. We observed high MMP-9 mRNA levels in TBL3 cells, but not in BL3 cells (Figure 1A). To verify reversal by the theilericidal drug Buvarvaquone, we tested different concentrations of Buparvaquone treatment on cell proliferation. The drug caused dramatic growth arrest in TBL3 cells, whereas BL3 growth was unaffected (Figure 1B). Using the standard dose concentration of 50 ng/ml for 64 hours (5), we observed a five-fold reduction in MMP-9 transcript levels in treated TBL3 cells, but no effect in BL3 cells (Figure 1C). Furthermore, we observed a similar Theileria-induction and Buparvaquone-reversibility of MMP-9 protein and protease activity by gelatin zymography (Figures 1D and 1E). Finally, we studied their invasive capacity using in vitro Matrigel invasion assays. TBL3 cells were highly invasive compared to BL3 cells, and Buparvaquone treatment reversed the phenotype (Figure 1F). Thus, the Theileria-inducible and Buparvaquone-reversible regulation of MMP-9 expression offers a model system to explore epigenetic control of this metastasis gene.

Figure 1. Inducible and reversible MMP-9 expression upon Theileria-transformation.

A) MMP-9 expression in infected (TBL3) and non-infected (BL3) cells by semiquantitative PCR analysis. mRNAs were incubated with or without Reverse Transcriptase (RT). Two housekeeping genes, GAPDH and HPRT1, were used as controls.

B) The relative number of TBL3 (squares) and BL3 (triangles) cells incubated with increasing concentrations of Buparvaquone assessed using the XTT assay. The arrow represents the concentration used for all subsequent experiments.

C) The reversibility of MMP-9 expression was assessed by qPCR analysis. Cells were treated with the drug Buparvaquone (BUP) for 64 hours. β-actin mRNA was used for normalization.

D) Western blot analysis of MMP-9 protein expression in TBL3/BL3 cells with/without Buparvaquone treatment for 64 hours. Bovine β-actin was used as a control. MW is the molecular weight marker (kDa).

E) Gelatin zymography to analyse MMP-9 protein activity in supernatants from BL3 and infected TBL3 cells with/without Buparvaquone treatment.

F) Invasion capacity tested using a modified Boyden chamber assay with/without Buparvaquone (BUP). Results show the number of invasive cells counted under the microscope. All results represent the average of three independent experiments (mean+/−sd)

*p<0.05, **p<0.01

Theileria induces chromatin marks on the bovine MMP-9 promoter

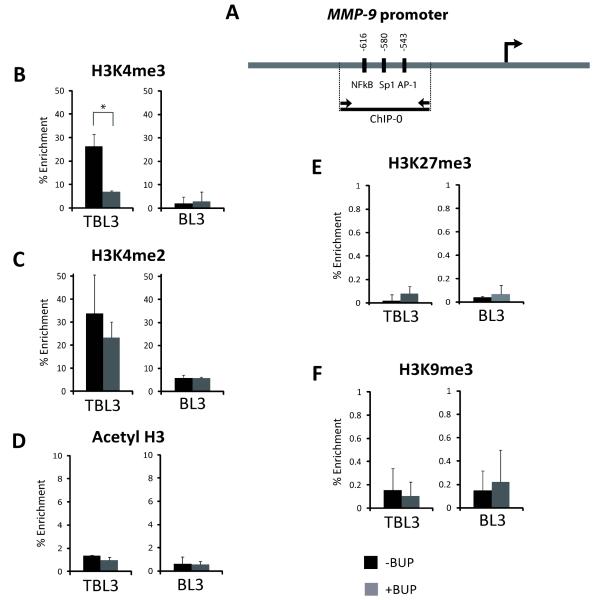

To explore epigenetic changes linked to MMP-9 regulation, we studied histone marks on the MMP-9 promoter focusing on a regulatory region (0.5 kb upstream from the TSS containing transcription factor binding sites AP-1, NF-κB, and Sp1) conserved between the bovine and human promoters (Figure 2A and S2). We performed Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies in TBL3 and BL3 cells, with and without Buparvaquone treatment, using antibodies specific for activating histone marks (i.e. Acetyl-H3, H3K4me2, H3K4me3), and repressive marks (i.e. H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) (Figure 2B-F). We observed enrichment of H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 marks in this region in TBL3 compared to BL3 cells (Figure 2B-2C). Furthermore, Buparvaquone treatment dramatically decreased H3K4me3 marks in TBL3 cells (but not H3K4me2), almost to the levels observed in BL3 cells (Figure 2B). In contrast, we observed no significant changes for Acetyl-H3, nor the repressive H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 marks, upon Theileria infection or Buparvaquone treatment (Figures 2D-2F). Thus, reversible Theileria-induced MMP-9 transcription is associated with dramatic changes in H3K4 tri-methylation on the MMP-9 promoter.

Figure 2. Chromatin analysis of bovine MMP-9 promoter upon Theileria infection.

A) Primers (ChIP-0) were designed to amplify by qPCR a sequence surrounding the NF-κB and AP-1 binding sites in the distal bovine MMP-9 promoter. The right arrow marks the transcription start site.

(B-F) BL3 and Theileria-infected TBL3 cells were incubated with/without Buparvaquone (BUP) for 64 hours. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation analysis with antibodies recognizing (B) H3K4me3, (C) H3K4me2, (D) Acetyl-H3, (E) H3K27me3 and (F) H3K9me3 marks. Error bars are representative of two independent experiments.

*p<0.05

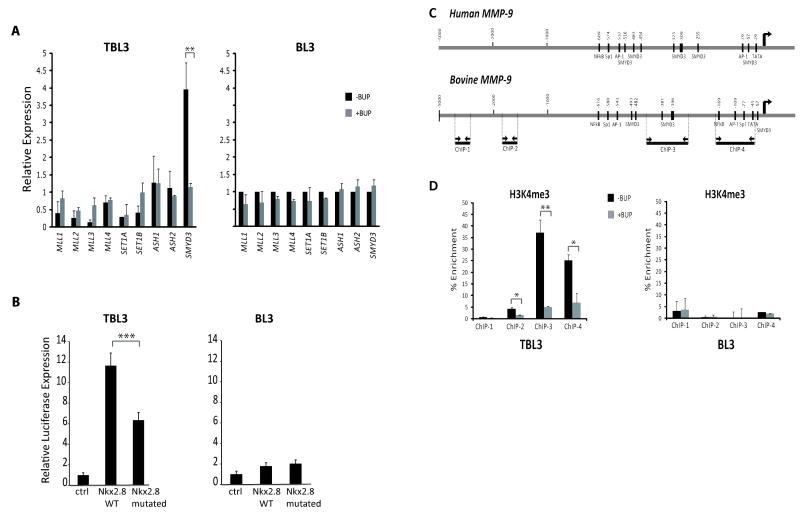

SMYD3 expression is induced by Theileria infection

To identify enzymes responsible for the H3K4-methyl marks on the MMP-9 promoter, we examined expression of a panel of H3K4 methyltransferases. Strikingly, SMYD3 was the only methyltransferase gene clearly induced by Theileria in TBL3 cells (over 4-fold induction) (Figure 3A). Furthermore, Buparvaquone treatment decreased SMYD3 expression to BL3 levels (Figure 3A). The bovine SMYD3 gene encodes a protein very similar to the human enzyme, with almost complete conservation of key SET domain residues (Figure S1). To test SMYD3 activity in these two cell lines, we transfected cells with a SMYD3 reporter construct containing the Nkx 2.8 promoter, a known SMYD3 target gene, coupled to Luciferase (24). This SMYD3 reporter was six-fold more active in TBL3 cells (Figure 3B). Furthermore, there was a significant reduction (50%) in the Luciferase levels when the SMYD3-binding site in the promoter was mutated (Figure 3B) (24). Thus, SMYD3 was a promising candidate as the methyltransferase responsible for elevated H3K4me2/me3 marks on the MMP-9 promoter.

Figure 3. SMYD3 methyltransferase is upregulated in Theileria-infected cells.

A) RT-qPCR analysis of the expression levels of H3K4-methyltransferases using RNA from Theileria-infected TBL3 or BL3 cells, with/without Buparvaquone treatment (BUP) for 64 hours. Beta-actin mRNA was used for normalization.

B) SMYD3 activity measured by a dual-luciferase assay in TBL3/BL3 cells transfected with a SMYD3 reporter (Wild-type Nkx2.8 WT promoter-Luciferase vector), compared to a control vector (Ctrl). Promoter activity was reduced when the SMYD3 binding site was mutated (Nkx2.8 mutated). Transfection efficiency was normalized with co-transfection of a Renilla-encoding plasmid.

C) Schematic of the human and bovine MMP-9 promoters highlighting potential SMYD3 binding sites. Oligonucleotides to amplify fragments of the bovine MMP-9 promoter: ChIP-1 (−4.7 kb upstream), ChIP-2 (−1.7 Kb), ChIP-3 (three putative SMYD3 binding sites) and ChIP-4 (proximal AP-1 site). The right arrows mark the transcription start site.

D) TBL3/BL3 cells were treated with/without Buparvaquone for 64 hours and Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed with an antibody recognizing H3K4me3. qPCR analysis was performed with the primer sets mentioned above. Error bars represent three independent experiments.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

SMYD3 binds to DNA via specific binding motifs (24) and bioinformatic analyses identified putative SMYD3 binding motifs in both the human and bovine MMP-9 promoters (Figure 3C, Figure S2). ChIP-qPCR analysis of the bovine MMP-9 promoter, using oligonucleotides that amplify a cluster of putative SMYD3 binding sites, revealed a marked enrichment for H3K4me3 modifications in this region in Theileria-infected cells (Figure 3D). Enrichment was reversed by Buparvaquone treatment and absent in BL3 cells (Figure 3D). These results suggested that SMYD3 binds to sites in the MMP-9 promoter to drive MMP-9 expression. Deeper investigation in TBL3/BL3 cells was hindered by the poor cross-reactivity of commercially-available antibodies with bovine SMYD3.

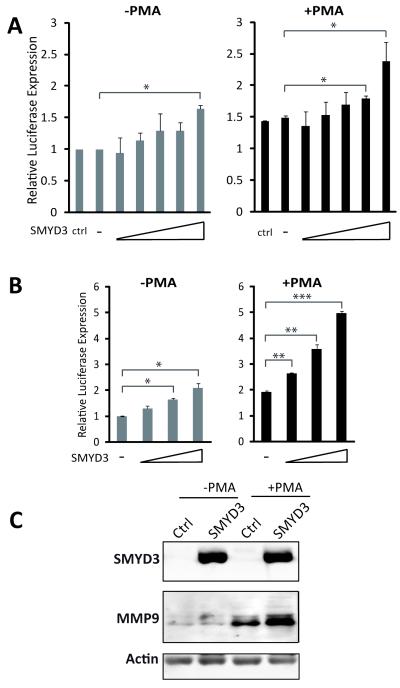

SMYD3 binds to the MMP-9 promoter and regulates transcription in human cancer cells

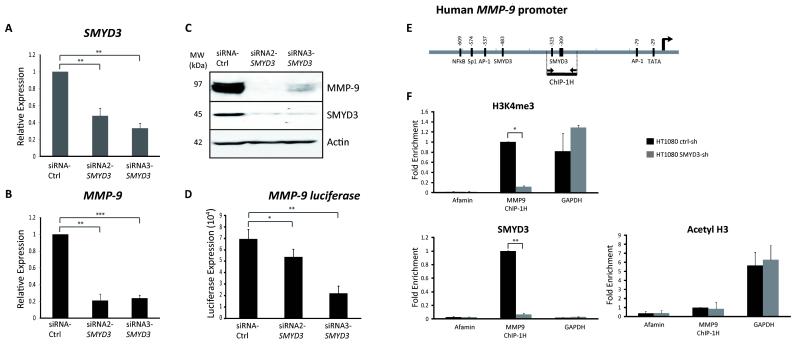

The putative SMYD3-binding motifs are conserved in the human MMP-9 promoter (Figure 3C, Figure S2), so we investigated the SMYD3-MMP-9 link further in human cancer cells. We studied a fibrosarcoma cell line, HT1080, which expresses MMP-9 and displays high invasive properties in vitro and in vivo (28, 29). We used an HT1080 derivative containing a 2.2 Kb MMP-9-Luc reporter stably integrated into the genome (26) to test SMYD3 effects on promoter activity in a chromosomal context (Figure 4A). We also tested SMYD3 function by transient co-transfection with a MMP-9-Luc reporter plasmid (Figure 4B). In both cases, SMYD3 transfection caused a modest, but statistically significant, increase in MMP-9 promoter activity (1.5-2.5 fold), which was enhanced by PMA treatment (2-5 fold) (Figure 4A-B). We observed similar synergistic effects on MMP-9 protein levels when SMYD3 was transfected with PMA stimulation (Figure 4C). We performed knockdown experiments using two different siRNA oligos that led to marked reduction in SMYD3 mRNA and protein (Figure 5A-5C). SMYD3 knockdown caused a significant decrease in MMP-9 mRNA and protein levels (Figure 5B-5C). Furthermore, siRNA SMYD3 caused a reduction in the activity of the MMP-9-Luc reporter integrated into the HT1080 genome (Figure 5D). These results support the hypothesis that SMYD3 regulates MMP-9 expression in human cancer cells.

Figure 4. SMYD3 induces MMP-9 expression in human fibrosarcoma cells.

A) The luciferase activity of an integrated MMP-9 reporter construct assessed in HT1080-2.2 cells, with increasing amounts of exogenous SMYD3 expression, with/without PMA treatment. The effects of SMYD3 transfection were compared to non-transfected controls (ctrl) and vector-transfected mock (-)** cells.

B) Luciferase assays showing expression of an MMP-9-luciferase construct transfected into HT1080 cells, with increasing amounts of ectopic SMYD3 expression, with/without PMA treatment compared to vector-transfected mock controls (-).

(C) Western blot analysis showing the expression of exogenous-transfected SMYD3 and upregulation of endogenous MMP-9 protein in HT1080 cells transfected with SMYD3 or control vectors (Ctrl), with/without PMA treatment.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Figure 5. SMYD3 knockdown causes epigenetic repression of MMP-9 in human fibrosarcoma cells.

A and B) HT1080 cells were transfected with two different siRNA oligonucleotides against SMYD3 or control followed by RTqPCR analysis of SMYD3 (A) and MMP-9 expression (B), 48 hours after transfection. GAPDH mRNA was used for normalization.

C) Western analysis in HT1080 cells transfected with two different siRNA oligonucleotides against SMYD3 or control siRNA, showing SMYD3 and MMP-9 proteins. β-actin was used as control. MW=molecular weight marker.

D) Luciferase activity in HT1080-2.2 cells with an integrated MMP-9 promoter-Luciferase reporter, following transfection with siRNA oligonucleotides against SMYD3 or control siRNA (Ctrl).

E) Amplicon surrounding putative SMYD3 binding sites (ChIP-1H) in the human MMP-9 promoter. The right arrow marks the transcription start site.

F) Chromatin Immunoprecipitation was performed with antibodies recognizing SMYD3, H3K4me3 or Acetylated-H3. GAPDH promoter is a positive control for the histone marks, and the Afamin promoter a negative control.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

We generated stable HT1080 cell lines expressing shRNA against SMYD3 and controls. SMYD3 reduction caused a decrease in MMP-9 mRNA and protein levels (Figure S3A-B). We performed ChIP and observed SMYD3 binding to the MMP-9 promoter in control cells, but not in knockdown cells (Figure 5F). Moreover, SMYD3 inhibition caused a significant decrease in the H3K4me3 marks on the MMP-9 promoter, but not on the control GAPDH promoter (Figure 5F). Also, SMYD3 inhibition did not affect H3-acetylation marks on the MMP-9 promoter (Figure 5F). We excluded the possibility of an indirect effect of SMYD3 knockdown on MMP-9 transcription via the modulation of chromatin modifiers known to participate in the regulation of MMP-9 (22). We found no evidence for altered expression of these regulators upon SMYD3 knockdown (Figure S4). Thus, SMYD3 binds directly to the human MMP-9 promoter and appears responsible for H3K4 methylation and transcriptional activation.

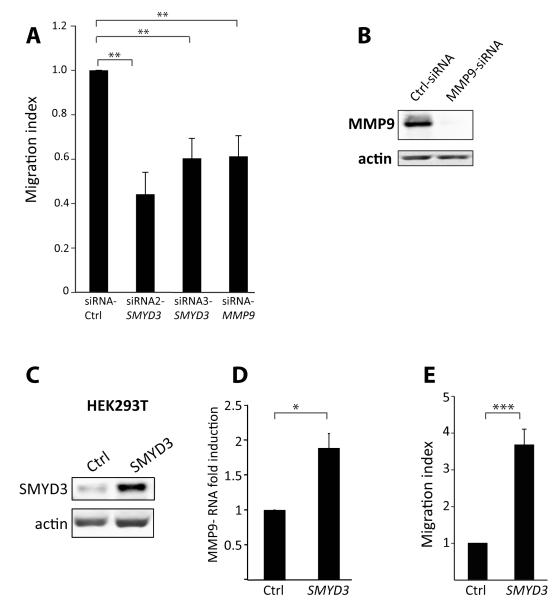

SMYD3 drives the invasiveness and proliferation of human cancer cells

To test whether SMYD3 regulation of MMP-9 contributes to tumor phenotypes, we examined the effect of SMYD3 knockdown using in vitro migration assays with collagen-coated filters. The down-regulation of SMYD3 using two independent siRNAs caused a significant reduction in the migratory capacity of HT1080 cells, similar to knocking down MMP-9 alone (Figure 6A-B). Conversely, we also tested the effect of over-expressing SMYD3 on cell migration; we transfected SMYD3 into human transformed HEK293T cells, which express low levels of endogenous SMYD3 (Figure 6C) and observed an upregulation of MMP-9 mRNA (Figure 6D) and a consequent increase in invasiveness (Figure 6E).

Figure 6. SMYD3 modulation affects cell migration of human cell lines.

A) HT1080 cells were transfected with two different siRNA oligonucleotides against SMYD3 or against MMP-9 or control siRNA (Ctrl), followed by analysis of cell migration on collagen-coated filters. Results are shown with respect to controls and error bars represent three independent experiments.

B) Western blot analysis showing the efficiency of siRNA MMP-9 knockdown in HT1080 cells. Beta-actin was used as control.

C) HEK293T cells were transfected with SMYD3-expressing vector or control vector (Ctrl). Exogenous SMYD3 protein levels were analysed by Western blot analysis and Beta-actin was used as control.

D) SMYD3 transfection into HEK293T cells caused an upregulation of endogenous MMP-9 levels as assessed by RT-qPCR analysis.

E) SMYD3 over-expression in HEK293T cells caused a significant increase in cell migration, compared to Control (Ctrl) transfected cells. Error bars represent three independent experiments.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

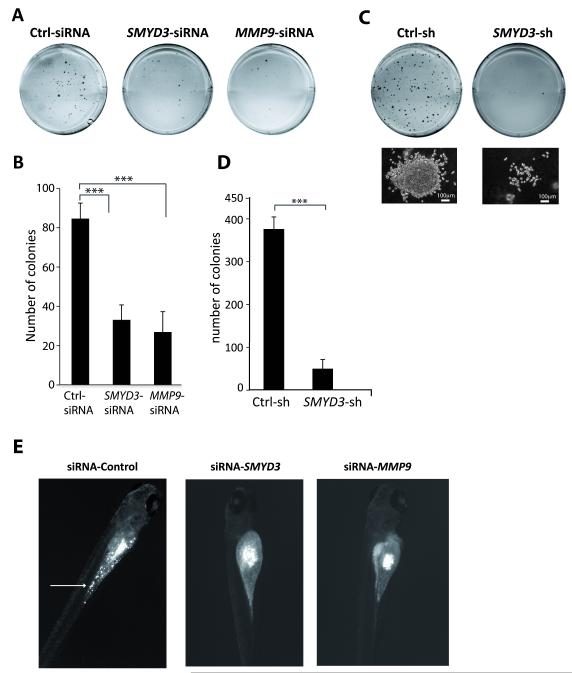

SMYD3 has also been implicated in tumor cell growth (24, 25). We found that knocking down SMYD3 (using siRNA or shRNA) HT1080 cells provoked a decrease in proliferation (Figure S3C), associated with an increased G1 phase and reduced S phase (Figure S3D). Strikingly, SMYD3 knockdown also reduced colony formation in soft-agar growth assays, a standard in vitro test for tumorigenic potential (Figure 7A-D). The few colonies that formed were small, with few dispersed cells (Figure 7C). Moreover, this effect could be phenocopied by depleting MMP-9 (Figure 7A-B), suggesting that these transformed phenotypes are linked to the regulation of MMP-9.

Figure 7. SMYD3 knockdown reduces tumor cell growth in vitro and invasion in vivo.

A) HT1080 cells were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides against SMYD3 or MMP-9 or control siRNA (Ctrl) followed by soft-agar colony formation assay. Representative wells for each condition are shown.

B) Average colony numbers for three independent experiments comparing Control, SMYD3 or MMP-9 siRNA transfected cells.

C-D) Colony formation assays (plates, photo micrographs of individual colonies, and colony numbers) as above, were performed using stable clones using shRNA against SMYD3 or control (Ctrl-sh).

E) Tumor dissemination in zebrafish embryos: HT1080 cells transfected with control (Ctrl-siRNA), SMYD3-siRNA or MMP9-siRNA were injected into the embryos. Images show representative examples of xenografted embryos. Disseminated tumor cells in the yolk are marked with an arrow.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Finally, we tested SMYD3 knockdown in vivo using a zebrafish xenotransplantation model (30) as a simple and effective system for testing cell invasion and metastasis formation of HT1080 cells. The embryos that developed tumors 72 hours post-injection were scored for the dissemination of tumor cells (Figure 7E, Table 1). We detected widely dispersed fluorescent spots in the yolk and in several cases in the tail region of zebrafish embryos in control xenografts, whereas the tumor mass detected in almost all of the embryos injected with SMYD3-siRNA or MMP9-siRNA treated cells exhibit no dissemination (Figure 7E, Table 1). Thus, SMYD3 expression levels affect the invasiveness and metastatic behavior of human tumor cells in vitro and in vivo.

Table 1.

Development of micrometastases after xenotransplantation of the HT1080 fibrosarcoma in the zebrafish model.

| siRNA Control | siRNA-SMYD3 | siRNA-MMP9 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of embryos with tumors |

74 | 32 | 29 |

| Dissemination in yolk | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| Dissemination in tail | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Dissemination in heart | 1 | 0 | 0 |

|

% total

dissemination |

20.3% | 3.80% | 3.40% |

DISCUSSION

The discovery of a large number of histone lysine methyltransferases and demethylases has revealed that histone methylation is a dynamic process directing the fine regulation of chromatin structure and gene expression (2, 31, 32). Yet it remains a significant challenge to dissect the precise series of epigenetic events in tumor progression, which is critical to develop targeted therapeutic strategies. It is particularly difficult to reconcile the global changes in histone modifications and enzymes, with localized effects on specific gene promoters (33, 34, 35). H3K4-methylation remains particularly intriguing, with examples of deregulated H3K4 methyltransferases (e.g. SMYD3) (24) and demethylases (e.g. PLU-1/JARID1B) (36-38). SMYD3 is interesting in this respect, as it binds to a specific DNA sequence, allowing it to target particular promoters (24). Here, we present evidence that SMYD3 is specifically upregulated upon Theileria-transformation and targets the promoter of the MMP-9 gene. This study offers insight into how Theileria parasites might mold the host cell epigenome and provides the first direct link between SMYD3 and a specific target gene in invasion and metastasis.

We focused on the MMP-9 gene as a paradigm to explore parasite-induced chromatin changes associated with host cell gene expression and invasion. MMP-9 is regulated extensively at the transcriptional level by classical transcription factors such as AP-1 and NF-κB (19). An elegant study by Ma and colleagues showed that these transcription factors lie downstream of signal transduction pathways and are recruited to the MMP-9 promoter in a stepwise process coordinated by chromatin modifying complexes (21). Although AP-1 activation is important for MMP-9 regulation upon Theileria infection, it is not sufficient, as some Theileria-transformed cell lines express AP-1 without activating MMP-9 (data not shown) (14). This drove us to search for epigenetic modulators that contribute to host gene regulation. We found that H3K4me3 was specifically associated with inducible and reversible MMP-9 expression (Figure 2). Surprisingly, we saw no changes in H3-acetylation, previously linked to MMP-9 regulation (21), nor in any repressive histone marks. SMYD3 was the only H3K4 methyltransferase whose expression correlated with the marks observed on the MMP-9 promoter. Our gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies demonstrated that SMYD3 plays a direct role in MMP-9 regulation. This is likely via binding to putative SMYD3 recognition motifs in the MMP-9 promoter and a multiple repeat (5′-CCCTCCCTCCC-3′) that is conserved between the bovine and human MMP-9 promoters (Figure S2). SMYD3 binding to this region appears essential for MMP-9 gene regulation. The effects of SMYD3 knockdown appear to be independent of the expression of other chromatin modifiers (21, 39) (Figure S4). But it is formally possible that SMYD3 and associated H3K4-methylation recruit additional regulatory proteins required for full MMP-9 induction (22). Another possibility is that promoter-bound SMYD3 contributes to gene expression by methylating non-histone proteins locally, such as the AP-1 transcription factor. There are precedents for transcription factor regulation by methylation and this merits further investigation (40). Our study highlights the dynamic nature of H3K4-methylation in transcriptional regulation and how methyltransferase binding to select promoters can control gene expression.

We provide the first evidence that Theileria parasites influence host cell gene expression by modulating epigenetic regulators. The inducible and reversible nature of MMP-9 expression provided a model gene to focus on chromatin events induced by the parasite, leading to the discovery of SMYD3 as a promising candidate. It is likely that other chromatin-modifying enzymes contribute to Theileria-induced transformation, just as multiple modifiers cooperate in human tumors (2). The Theileria system offers an attractive model to search for novel SMYD3 target genes, by comparing infected and Buparvaquone-treated transcriptomes accompanied by genome-wide ChIP analysis. One intriguing aspect is the striking upregulation of solely SMYD3 and not other H3K4 methyltransferases, such as MLL members that are deregulated in human cancers and regulate MMP-9 (41). SMYD3 is overexpressed in human colorectal and hepatocellular carcinomas (24) and breast cancer cells (25). Elevated SMYD3 expression was recently observed in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) and in highly metastatic pancreatic cancers (42). However, little is known about SMYD3 transcriptional control (43) and our model provides a tool for studying the inducible and reversible regulation of SMYD3 in cancer cells. Our results showing that the SMYD3-MMP9 circuit is functional in human cells, demonstrates that the Theileria model can be effectively used to generate mechanistic hypotheses to be tested in human cancers.

Our study directly links the SMYD3 methyltransferase to the MMP-9 gene, which is important in angiogenesis and metastasis. MMP-9 expression is linked to lymphoma, leukemia and metastasis (44, 45). There are few characterized targets for SMYD3 in tumorigenesis, except for the hTERT telomerase and WNT10B genes (25, 39). Previous studies highlighted the role of SMYD3 in cancer proliferation, but those linking SMYD3 to invasion have not identified a direct molecular target (24, 25, 46, 47). SMYD3 was also identified in gene signatures in metastatic pancreatic tumors (42). The urgent need to develop better therapies for metastatic disease makes it important to identify targets of regulators induced in metastatic cells. Clinical trials using MMP inhibitors have been hampered by problems with selectivity (48). Thus, our finding that a histone methyltransferase, which is induced in metastatic tumors, specifically regulates MMP-9 expression and tumor invasion in vivo, offers a target to develop therapeutic strategies aimed at preventing cancer progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Claire Rougeulle and Slimane Ait-Si-Ali for critical reading of the manuscript and members of UMR7216 for helpful discussions. We thank Carmen Garrido for suggesting the zebrafish experiments and André Bouchot for fluorescent microscopy assistance.

Grant Support The Weitzman laboratory was supported by Fondation de France (FdF #2102), Association pour le Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC Fixe #4975, ARC-Equipement #7990) and Association for International Cancer Research (AICR, #08-0111). Langsley laboratory acknowledges funding from Wellcome Trust grant (075820/A/04/Z) and Inserm/CNRS infrastructure support. ACR was supported by Colfuturo (Colombia), ARC and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM #FDT20100920170). NJ was supported by Université Paris-Diderot and AXA Research Fund.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:286–98. doi: 10.1038/nrg2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaussepied M, Langsley G. Theileria transformation of bovine leukocytes: a parasite model for the study of lymphoproliferation. Res Immunol. 1996;147:127–38. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(96)83165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobbelaere D, Heussler V. Transformation of leukocytes by Theileria parva and T. annulata. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:1–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lizundia R, Chaussepied M, Huerre M, Werling D, Di Santo JP, Langsley G. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase/c-Jun signaling promotes survival and metastasis of B lymphocytes transformed by Theileria. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6105–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaussepied M, Janski N, Baumgartner M, Lizundia R, Jensen K, Weir W, et al. TGF-b2 induction regulates invasiveness of Theileria-transformed leukocytes and disease susceptibility. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001197. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somerville RP, Adamson RE, Brown CG, Hall FR. Metastasis of Theileria annulata macroschizont-infected cells in scid mice is mediated by matrix metalloproteinases. Parasitology. 1998;116(Pt 3):223–8. doi: 10.1017/s0031182097002151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobbelaere DA, Coquerelle TM, Roditi IJ, Eichhorn M, Williams RO. Theileria parva infection induces autocrine growth of bovine lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:4730–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muraguri GR, Kiara HK, McHardy N. Treatment of East Coast fever: a comparison of parvaquone and buparvaquone. Vet Parasitol. 1999;87:25–37. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(99)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galley Y, Hagens G, Glaser I, Davis W, Eichhorn M, Dobbelaere D. Jun NH2-terminal kinase is constitutively activated in T cells transformed by the intracellular parasite Theileria parva. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5119–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaussepied M, Lallemand D, Moreau MF, Adamson R, Hall R, Langsley G. Upregulation of Jun and Fos family members and permanent JNK activity lead to constitutive AP-1 activation in Theileria-transformed leukocytes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;94:215–26. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heussler VT, Rottenberg S, Schwab R, Kuenzi P, Fernandez PC, McKellar S, et al. Hijacking of host cell IKK signalosomes by the transforming parasite Theileria. Science. 2002;298:1033–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1075462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adamson RE, Hall FR. Matrix metalloproteinases mediate the metastatic phenotype of Theileria annulata-transformed cells. Parasitology. 1996;113(Pt 5):449–55. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000081518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adamson R, Logan M, Kinnaird J, Langsley G, Hall R. Loss of matrix metalloproteinase 9 activity in Theileria annulata-attenuated cells is at the transcriptional level and is associated with differentially expressed AP-1 species. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;106:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baylis HA, Megson A, Hall R. Infection with Theileria annulata induces expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 and transcription factor AP-1 in bovine leucocytes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;69:211–22. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00216-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van den Steen PE, Dubois B, Nelissen I, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Opdenakker G. Biochemistry and molecular biology of gelatinase B or matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;37:375–536. doi: 10.1080/10409230290771546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato H, Seiki M. Regulatory mechanism of 92 kDa type IV collagenase gene expression which is associated with invasiveness of tumor cells. Oncogene. 1993;8:395–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gum R, Lengyel E, Juarez J, Chen JH, Sato H, Seiki M, et al. Stimulation of 92-kDa gelatinase B promoter activity by ras is mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1-independent and requires multiple transcription factor binding sites including closely spaced PEA3/ets and AP-1 sequences. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10672–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan C, Boyd DD. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:19–26. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma Z, Shah RC, Chang MJ, Benveniste EN. Coordination of Cell Signaling, Chromatin Remodeling, Histone Modifications, and Regulator Recruitment in Human Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 Gene Transcription. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;24:5496–509. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5496-5509.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao X, Benveniste E. Transcriptional Activation of Human Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Gene Expression by Multiple Co-activators. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2008;383:945–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theilen GH, Rush JD, Nelson-Rees WA, Dungworth DL, Munn RJ, Switzer JW. Bovine leukemia: establishment and morphologic characterization of continuous cell suspension culture, BL-1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1968;40:737–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamamoto R, Furukawa Y, Morita M, Iimura Y, Silva FP, Li M, et al. SMYD3 encodes a histone methyltransferase involved in the proliferation of cancer cells. Nature Cell Biology. 2004;6:731–40. doi: 10.1038/ncb1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamamoto R, Silva FP, Tsuge M, Nishidate T, Katagiri T, Nakamura Y, et al. Enhanced SMYD3 expression is essential for the growth of breast cancer cells. Cancer Science. 2006;97:113–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan C, Wang H, Aggarwal B, Boyd DD. A novel homologous recombination system to study 92 kDa type IV collagenase transcription demonstrates that the NF-kappaB motif drives the transition from a repressed to an activated state of gene expression. FASEB J. 2004;18:540–1. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0960fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adamson R, Hall R. A role for matrix metalloproteinases in the pathology and attenuation of Theileria annulata infections. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:390–3. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim A, Kim MJ, Yang Y, Kim JW, Yeom YI, Lim JS. Suppression of NF-kappaB activity by NDRG2 expression attenuates the invasive potential of highly malignant tumor cells. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:927–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HK, Zhang H, Li H, Wu TT, Swisher S, He D, et al. Slit2 inhibits growth and metastasis of fibrosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1411–20. doi: 10.1593/neo.08804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marques IJ, Weiss FU, Vlecken DH, Nitsche C, Bakkers J, Lagendijk AK, et al. Metastatic behaviour of primary human tumours in a zebrafish xenotransplantation model. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenuwein T. The epigenetic magic of histone lysine methylation. FEBS J. 2006;273:3121–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Villar-Garea A, Boix-Chornet M, Espada J, Schotta G, et al. Loss of acetylation at Lys16 and trimethylation at Lys20 of histone H4 is a common hallmark of human cancer. Nature Genetics. 2005;37:391–400. doi: 10.1038/ng1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kondo Y, Shen L, Issa JP. Critical role of histone methylation in tumor suppressor gene silencing in colorectal cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:206–15. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.206-215.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viré E, Brenner C, Deplus R, Blanchon L, Fraga M, Didelot C, et al. The Polycomb group protein EZH2 directly controls DNA methylation. Nature. 2005;439:871–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Haaften G, Dalgliesh GL, Davies H, Chen L, Bignell G, Greenman C, et al. Somatic mutations of the histone H3K27 demethylase gene UTX in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41:521–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, Chen L, Bignell G, Butler A, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463:360–3. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi Y. Histone lysine demethylases: emerging roles in development, physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:829–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu C, Fang X, Ge Z, Jalink M, Kyo S, Bjorkholm M, et al. The Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (hTERT) Gene Is a Direct Target of the Histone Methyltransferase SMYD3. Cancer Research. 2007;67:2626–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sterner DE, Berger SL. Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:435–59. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.2.435-459.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robert I, Aussems M, Keutgens A, Zhang X, Hennuy B, Viatour P, et al. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 gene induction by a truncated oncogenic NF-kappaB2 protein involves the recruitment of MLL1 and MLL2 H3K4 histone methyltransferase complexes. Oncogene. 2009;28:1626–38. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakamura T, Fidler IJ, Coombes KR. Gene expression profile of metastatic human pancreatic cancer cells depends on the organ microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2007;67:139–48. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuge M, Hamamoto R, Silva FP, Ohnishi Y, Chayama K, Kamatani N, et al. A variable number of tandem repeats polymorphism in an E2F-1 binding element in the 5′ flanking region of SMYD3 is a risk factor for human cancers. Nature Genetics. 2005;37:1104–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bauvois B, Dumont J, Mathiot C, Kolb JP. Production of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in early stage B-CLL: suppression by interferons. Leukemia. 2002;16:791–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Kempen LC, Coussens LM. MMP9 potentiates pulmonary metastasis formation. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:251–2. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luo XG, Xi T, Guo S, Liu ZP, Wang N, Jiang Y, et al. Effects of SMYD3 overexpression on transformation, serum dependence, and apoptosis sensitivity in NIH3T3 cells. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:679–84. doi: 10.1002/iub.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zou J-N, Wang S-Z, Yang J-S, Luo X-G, Xie J-H, Xi T. Knockdown of SMYD3 by RNA interference down-regulates c-Met expression and inhibits cells migration and invasion induced by HGF. Cancer Letters. 2009;280:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coussens LM, Fingleton B, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer: trials and tribulations. Science. 2002;295:2387–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.