Abstract

Background

WNT7a, a member of the Wnt ligand family implicated in several developmental processes, has also been reported to be dysregulated in some types of tumors; however, its function and implication in oncogenesis is poorly understood. Moreover, the expression of this gene and the role that it plays in the biology of blood cells remains unclear. In addition to determining the expression of the WNT7A gene in blood cells, in leukemia-derived cell lines, and in samples of patients with leukemia, the aim of this study was to seek the effect of this gene in proliferation.

Methods

We analyzed peripheral blood mononuclear cells, sorted CD3 and CD19 cells, four leukemia-derived cell lines, and blood samples from 14 patients with Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and 19 clinically healthy subjects. Reverse transcription followed by quantitative Real-time Polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis were performed to determine relative WNT7A expression. Restoration of WNT7a was done employing a lentiviral system and by using a recombinant human protein. Cell proliferation was measured by addition of WST-1 to cell cultures.

Results

WNT7a is mainly produced by CD3 T-lymphocytes, its expression decreases upon activation, and it is severely reduced in leukemia-derived cell lines, as well as in the blood samples of patients with ALL when compared with healthy controls (p ≤0.001). By restoring WNT7A expression in leukemia-derived cells, we were able to demonstrate that WNT7a inhibits cell growth. A similar effect was observed when a recombinant human WNT7a protein was used. Interestingly, restoration of WNT7A expression in Jurkat cells did not activate the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first report evidencing quantitatively decreased WNT7A levels in leukemia-derived cells and that WNT7A restoration in T-lymphocytes inhibits cell proliferation. In addition, our results also support the possible function of WNT7A as a tumor suppressor gene as well as a therapeutic tool.

Keywords: WNT7A, Wnt signaling, Leukemia, Anti-proliferative, Non-canonical pathway

Background

The Wnt signaling pathway describes a complex network of proteins involved in differentiation, proliferation, migration, and cell polarity, which play important roles during embryonic development, tissue regeneration, and in homeostatic mechanisms [1,2]. Wnt molecules are a highly conserved group of secreted cysteine-rich lipoglycoproteins that work as signaling molecules. Nineteen different Wnt family members have been described in humans to date. The binding of these ligands to its receptor complex (Frizzled/LRP-5/6) leads to activation of the pathway [1,3]. Distinct sets of Wnt and Frizzled ligand-receptor pairs can activate different pathways and lead to unique cellular response [3,4]. Wnt signals are transduced through at least three different intracellular pathways: Wnt/β-catenin, also known as canonical pathway; Wnt/Ca++, and the Planar cell polarity (Wnt/JNK) pathway [1,3,5]. In the canonical pathway, receptor activation leads to stabilization of β-catenin by inhibiting the phosphorylation activity of the Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β. Unphosphorylated β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm and then translocates into the nucleus, activating target gene expression through a complex network of co-receptors (TCF/LEF transcription factors) and repressors (Groucho) [6-8]. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is involved in the self-renewal and proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells and has been also implicated in numerous types of cancers [7,9,10]. Dysregulation of this pathway is a hallmark of several types of tumors [7,11-13].

Leukemic cells are highly heterogeneous, and their mechanisms of tumorigenesis are poorly understood. Recently, dysregulation of the Wnt signaling pathway has been implicated in the pathogenesis of some leukemia types [14-17]. Moreover, different expression profiles of some WNT genes and their related signaling molecules have been reported in hematological cancers [12,18-22]. However, there are limited numbers of studies regarding the role of WNT7a, both in normal and in leukemia-derived cells [19,23,24].

Because our group has observed strongly decreased expression of WNT7A in different tumor-derived cell lines (unpublished data), we have focused our attention on the expression of WNT7A in normal peripheral blood cells, in leukemia-derived cell lines, and in patients with Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Methods

Ethics statement

Fourteen peripheral blood samples from patients with leukemia were collected from the Hospital Civil Fray Antonio Alcalde and blood samples from healthy volunteers at the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) Blood Bank after approval by the Ethical and Research Committee No. 1305 of the Centro de Investigación Biomédica de Occidente (CIBO) - IMSS (project approval numbers 1305-2006-07 and 1305-2010-2). Written informed consent from patients and healthy volunteers (following local Ethics Committee guidelines and international norms) was also required prior to blood sample collection.

Cell line culture

The human leukemia-derived cell lines Jurkat, K562, CEM, HL60, and the BJAB cells (lymphoma-derived B cells) were used as study model. Jurkat and CEM possess a lymphoblastic phenotype, whereas K562 and HL60 have a myeloid origin. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% Fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. All products mentioned previously were obtained from the GIBCO™ Invitrogen Corporation.

Sorting of CD3- and CD19-positive cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) obtained from five healthy volunteers (12 mL of peripheral blood) were isolated by density-gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Paque™ PLUS (GE Healthcare). PBMC included lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, NK cells, and also basophils and dendritic cells. These cells can be extracted from whole blood using Ficoll, which separates the blood into a top layer of plasma, followed by a layer of PBMC and a bottom fraction of polymorphonuclear cells and erythrocytes. The PBMC were resuspended in PBS and stained with an anti-CD3 antibody (sc-1179-FITC, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to select T-lymphocytes and with an anti-CD19 antibody (sc-19650-PE, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to select B-lymphocytes. After incubation with both antibodies, cells were washed and positive cells for CD3 or CD19 were sorted on a FACSAria (Becton Dickinson).

RNA isolation

Leukemia-derived cell lines were seeded at a density of 5 × 106 in 75-cm3 flasks and harvested after 24 h for Total RNA extraction by using the PureLink™ Micro-to-Midi Total RNA Purification System (cat. no. 12183-018, Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturers. RNA from PBMC, CD3+ and CD19+cells was also extracted from five healthy volunteers by this method and put together to create a representative sample group of each cell type for the qRT-PCR analysis.

Peripheral blood samples were collected from patients with ALL at the Hospital Civil Fray Antonio Alcalde. Additionally, 19 blood samples from healthy donors were collected as normal controls from the IMSS-Blood Bank (Table 1). Each sample (5 mL) was collected with EDTA as anticoagulant, mixed immediately after collection with 45 mL of RNA/DNA Stabilization Reagent for Blood/Bone marrow (Roche Applied Science), and stored at -80°C for conservation. From the stabilized samples, we took a volume corresponding to 6 × 105 leukocytes for each patient or control and utilized this for mRNA isolation via a two-step procedure through magnetic separation employing the mRNA Isolation Kit for blood/bone marrow (Roche Applied Science). mRNA was finally eluted from the magnetic pearls in 20 μL of water and stored at -80°C until use.

Table 1.

Gender and Age of Control and Patients

| Control ID | Gender | Age | Patient ID | Gender | Age | Diagnostic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 33 | 1 | M | 38 | ALL |

| 2 | M | 26 | 2 | M | 82 | ALL |

| 3 | F | 54 | 3 | M | 56 | ALL |

| 4 | F | 34 | 4 | F | 46 | ALL |

| 5 | F | 68 | 5 | F | 32 | ALL |

| 6 | M | 51 | 6 | F | 36 | ALL |

| 7 | F | 43 | 7 | F | 56 | ALL |

| 8 | F | 24 | 8 | M | 84 | ALL |

| 9 | F | 56 | 9 | M | 61 | ALL |

| 10 | M | 40 | 10 | M | 58 | ALL |

| 11 | F | 53 | 11 | F | 30 | ALL |

| 12 | F | 35 | 12 | M | 52 | ALL |

| 13 | F | 26 | 13 | F | 43 | ALL |

| 14 | M | 39 | 14 | M | 18 | ALL |

| 15 | M | 73 | 15 | F | 47 | CLL |

| 16 | M | 45 | 16 | F | 31 | CLL |

| 17 | F | 39 | 17 | F | 37 | CLL |

| 18 | M | 40 | 18 | F | 58 | CLL |

| 19 | M | 26 | 19 | F | 89 | CLL |

| 20 | F | 56 | AML | |||

| 21 | F | 82 | AML | |||

| 22 | M | 40 | AML | |||

| 23 | M | 55 | AML | |||

| 24 | F | 33 | CML | |||

| 25 | M | 35 | CML | |||

| 26 | M | 46 | CML | |||

cDNA synthesis

For cell lines, cDNA synthesis was performed from 5 μg of total RNA. For patients or healthy volunteers, we used the maximum volume of mRNA permitted in the kit (8 μL). cDNA was obtained by using the SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis System primed with oligo(dT) (cat. no. 18080051, Invitrogen). The protocol was carried out as recommended by the manufacturers.

Primer design and qRT-PCR assays

Primers were designed using Oligo-Primer Analysis Software, version 6.51 (Molecular Biology Insights, Inc., USA) from sequences obtained from the GenBank Nucleotide database of the NCBI website. Primers were synthesized by Invitrogen Corporation, USA. The primers sequence, the location of each primer, the gene symbol, the sequence accession number, the amplicon length, and the annealing temperature used are summarized in Table 2. The extension time used for each set of primers was set by dividing the amplicon size by 25 sec, because the polymerase has the capability to insert 25 bp per second.

Table 2.

Information of the oligonucleotides used for the qRT-PCR analysis

| Gene Name | Sequence Accession Number | Primer Sequence | Primer Location (Exon | Prod. Length | T°a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WNT7A | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 7A | NM_004625 | F CAAAGAGAAGCAAGGCCAGTA R GTAGCCCAGCTCCCGAAACTG |

707-730 (3) 962-983 (4) |

277 | 60 |

| MYC | V-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog (avian) | NM_002467.4 | F CCAGCGCCTTCTCTCCGTC R GGGAGGCGCTGCGTAGTTGT |

1208-1226 (2) 1490-1509 (3) |

302 | 60 |

| JUN | Jun proto-oncogene | NM_002228.3 | F TGGAAAGTACTCCCCTAACCT R CTGAAACATCGCACTATCCTT |

2786-2806 (1) 3015-3035 (1) |

250 | 60 |

| FRA-1 | FOS-like antigen 1 | NM_005438.3 | F AGGAACCGGAGGAAGGAACTG R TGCCACTGGTACTGCCTGTGT |

554-574 (3) 732-752 (4) |

199 | 60 |

| AXIN2 | Axin 2 | NM_004655.3 | F AAAAAGGGAAATTATAGGTATTAC R CGATTCTTCCTTAGACTTTG |

2678-2701 (10/11) 2935-2954 (11) |

277 | 54 |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | NM_002046.3 | F CACTGCCACCCAGAAGACTGTG R TGTAGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC |

645-666 (8) 1072-1089 (9) |

449 | 63 |

| RPL32 | Ribosomal protein L32 | NM_000994.3 | F GACTTGACAACAGGGTTCGTAG R ATTTAAACAGAAAACGTGCACA |

213-234 (3) 511-532 (4) |

320 | 60 |

| RPS18 | Ribosomal protein S18 | NM_022551.2 | F CGATGGGCGGCGGAAAA R CAGTCGCTCCAGGTCTTCACGG |

105-121 (2) 366-387 (5) |

283 | 58 |

| B2M | Beta-2-microglobulin | NM_004048.2 | F GAGGCTATCCAGCGTACTCCAA R CACACGGCAGGCATACTCAT |

115-136 (1/2) 347-366 (2) |

252 | 58 |

| ACTB | Actin beta | NM_001101.3 | F TCCGCAAAGACCTGTACG R AAGAAAGGGTGTAACGCAACTA |

950-967 (5) 1226-1247 (6) |

298 | 60 |

Gene expression analysis was achieved by qRT-PCR on the 1.5 LightCycler® (Roche Diagnostics) using the LightCycler-FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I Kit (cat. no. 03515885001, Roche Applied Science) as recommended by the manufacturers. A standard curve with four serial dilution points and a negative control were included in each run. Relative expression was calculated with LightCycler software version 4.1 by taking GAPDH, RPL32, or RPS18 as reference genes.

Analysis in cell lines was performed by taking the values obtained from two independent RNA extractions in duplicate. In patients and healthy volunteers, experiments were performed three times in each individual sample.

In order to demonstrate that the reference genes selected and used in our cell model were appropriate, some samples were also tested with additional reference genes, as shown in Additional File 1.

Δ CP analysis

For analysis of WNT7A expression in patients and in healthy volunteers, we used ΔCP to facilitate analysis by taking only intrinsic references from each sample. We compared the ΔCP values obtained for both groups, i.e., the WNT7A CP minus the reference gene CP from the same sample. GAPDH and RPL32 were used for normalization in this analysis. It is very important to point out that ΔCP is inversely proportional to the expression of the target gene.

Isolation and culture of mononuclear cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of healthy volunteers were isolated by density gradient using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare, Sweden). Blood with anticoagulant was diluted 1:1 in PBS without MgCl2 and subsequently 1:1 in Ficoll-Paque PLUS. After 30-min centrifugation at 1,500 rpm, the cells' pellet was washed with PBS and resuspended in RPMI medium complemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Cells were led to growth at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in the presence or absence of phytohemagglutinin (PHA - 2 μg/mL).

Treatment with WNT7a recombinant protein

Jurkat and PBMC were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells in a 96-well microtiter plate in 200 μL of RPMI medium. Recombinant human WNT7a (cat. no. 3008-WN/CF, R&D Systems) was resuspended first in sterile PBS and was afterward diluted 1:100 in the cell culture medium. Every 24 h the recombinant protein was added fresh to each well at a final concentration of 3 μg/mL; incubations at 37°C were performed for 24 and 48 h.

Measurement of cell survival

After WNT7A overexpression or treatment with WNT7a recombinant protein, cell survival was determined by cleavage of tetrazolium salt WST-1 to formazan (cat. no. 11 644 807 001, Roche Applied Science) by reading the absorbance of treated and untreated cells at 440 nm on a microtiter plate reader (Synergy™ HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader. Biotek. Winooski, VT, USA). The value of untreated cells was used as 100% cell survival.

Cloning WNT7A

WNT7A Open reading frame (ORF) (GeneID: 7476; NM _004625) was amplified from human non-tumorigenic keratinocytes utilizing the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (cat. no. 11 732 650 001, Roche Applied Science) with the following set of primers: forward 5'-GGG ACT ATG AAC CGG AAA GC -3'; reverse: 5'- CGG GGC TCA CTT GCA CGT GTA C -3'. Afterward, the PCR product was cloned into the pCR2.1TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Construction was sequenced employing M13 Forward and Reverse primers (Invitrogen) with the BigDye® Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). After corroborating the WNT7A sequence with that reported in GenBank, WNT7A ORF was isolated from pCR2.1TOPO vector by EcoRI restriction and subcloned into the EcoRI site of the lentiviral expression vector pLVX-Puro or pLVX-Tight-Puro (Clontech Laboratories, USA).

Lentivirus production and infection

To produce infectious viral particles, Lenti-X 293 T cells were transient-transfected by the Lentiphos HT/Lenti-X HT Packaging Systems with the lentiviral vectors pLVX-Puro or pLVX-WNT7A-Puro as described by the manufacturers (Clontech Laboratories. USA). Tet-Express Inducible Expression Systems were also used (pLVX-Tet-On Advanced and pLVX-Tight-WNT7A-Puro). After 48 h, supernatants were checked with Lenti-X GoStix (Clontech Laboratories. USA) to determine whether sufficient viral particles were produced before transducing target cells. Supernatants were filtered through a 0.45-μm PES filter to eliminate detached cells, were aliquoted, and subsequently stored at -80°C until use. Jurkat cells were transduced with 200 μL of supernatants obtained with pLVX-Puro or pLVX-WNT7A-Puro. RNA and protein extractions were obtained after 2 days of transduction and 1 week of puromycin selection (1 μg/mL). Cell proliferation was also measured by adding WST-1 to the culture cells at this point.

For inducible WNT7A expression in the leukemia-derived cell lines, cells were first transduced with the pLVX-Tet-On (regulator vector) and selected with G418 (cat. no. 631307, Clontech Laboratories, USA). Afterward, cells were transduced with the pLVX-Tight-WNT7A-Puro and selected with Puromycin for 2 weeks (1.5 μg/mL). After selection, cells were grown in the absence or presence of Doxycycline (Doxy) (750 ng/mL) to overexpress WNT7A.

Western blot assays

Cells were harvested by scraping and were lysed with RIPA buffer by sonication (15 pulses, 50% amp). Extracts were incubated for 30 min at 4°C and obtained by centrifugation (14,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad DC Protein Kit (cat. no. 500-0114 Protein DC - BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and 50 μg of whole-cell extracts were electrophoresed in 12% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore) and incubated with 1% Western blocking reagent (cat no. 11921681001, Roche, Germany) to block nonspecific binding. Primary antibodies were incubated over night at 4°C and the secondary antibodies were incubated with the membrane for 2 h at RT, followed by chemiluminescent detection using Immobilon Western substrate (Millipore Corporation, USA) with the ChemiDoc XRS (Biorad Laboratories, USA). The primary antibodies used were: anti-β-Catenin (cat. no. SC-7199, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), anti-WNT7A (cat. no. AF3008 and cat. no. K-15, from R&D and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, respectively), or anti-β-Actin (cat. no. SC-26361, Santa Cruz, Biothechnology).

Apoptosis detection

Cell death was measured by flow cytometry using propidium iodide (cat. no. P4864, Sigma-Aldrich) and Annexin-V-FLUOS (cat. no. 1828681, Roche Applied Science) as recommended by these manufacturers. Cells were seeded at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells per flask in 10 mL RPMI medium with or without Doxycycline (750 ng/mL). After a 72 h incubation, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with Annexin and propidium iodide for 15 min; 10,000 events from each sample were analyzed in a FACS Aria cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics software version 17.0. Post-hoc tests (Tukey HSD, Bonferroni, and Dunnett 3 T) were utilized for multiple comparisons between groups, and one-way ANOVA was employed to compare the means among more than two different groups. Only p values < 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

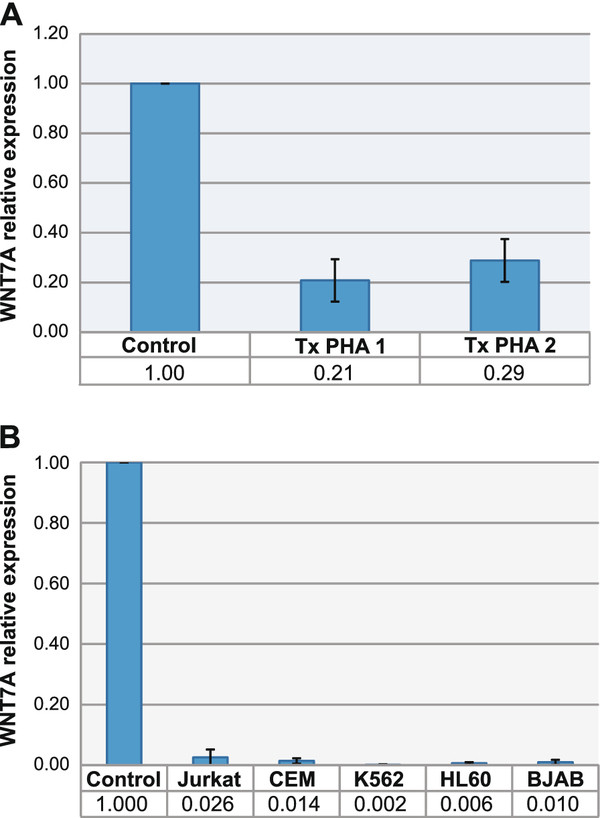

T-lymphocytes are the main cell population in peripheral blood that expresses WNT7A

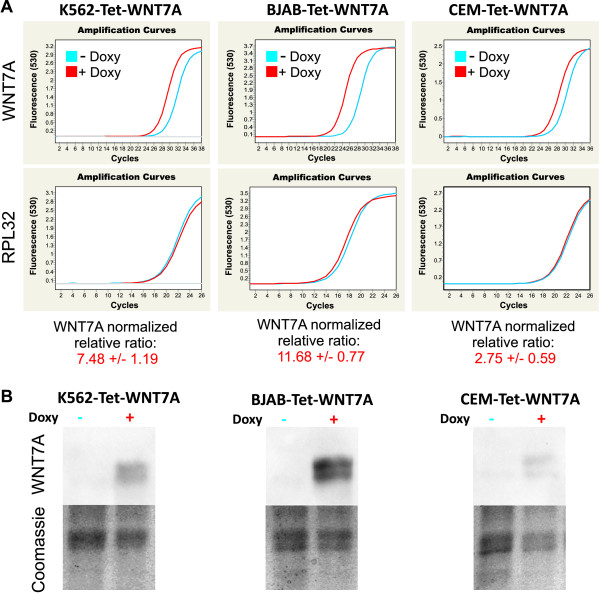

The expression of WNT7A in normal mature blood cells is still not well characterized. From this starting point, we wanted to know whether normal peripheral blood cells express WNT7A and, more specifically, if T- or B-lymphocytes are expressing this Wnt ligand at the same level. In order to address this goal, we obtained cDNA from total blood cells, PBMC, T-lymphocytes (CD3+ cells), and B-lymphocytes (CD19+ cells)-positive cells. CD3+ and CD19+ cells were sorted by Flow cytometry (FCM) from healthy volunteers' PBMC (Figure 1A). Afterward, we determined the expression of WNT7A by qRT-PCR in the groups mentioned previously utilizing GAPDH, RPL32, and RPS18 as reference genes for relative expression analysis. Because efficiency and error of reactions are important for relative quantification analysis, standard curves obtained by serial dilutions (1:1, 1:2, 1:4, and 1:8) of cDNA were included in each PCR (see Additional File 1). Only data from PCR reactions showing an error < 0.04 and an efficiency of at least 1.8 were included in the analysis. Because CD3- and CD19-sorted cells were isolated from PBMCs, we normalized all values to those obtained in the PBMC. We found expression of WNT7A in total peripheral blood cells, but interestingly, we observed approximately 84% lower WNT7A expression in these cells than in PBMC (in which WNT7A relative expression was set as 1) (Figure 1B). Taking into account that 80% of peripheral blood cells are from myeloid origin and that 80% of PBMC are lymphoid, we assume that myeloid cells are expressing very low levels of WNT7A and that the main producers could be lymphoid cells. To delve deeper into this question, we analyzed the relative expression of WNT7A in pure CD3+ and CD19+ cells. We could determine that the highest expression of WNT7A corresponds to CD3+ cells; in contrast, CD19+ cells express nearly undetectable levels of this ligand. The WNT7A relative-expression difference observed between PBMC and CD3+ cells correlates with the expected population's percentage of T-lymphocytes (~50-75%), B-lymphocytes (~10-25%), and NK cells (~5-20%) in PBMC. Summarizing these data, WNT7A expression rises to the greatest degree from CD3+ cells.

Figure 1.

Expression of WNT7A in total peripheral blood cells, Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), sorted CD3+ and CD19+ cells obtained from healthy volunteers' samples. (A) Dot blot graphics showing the selected region for sorting (upper left panel), CD3-Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and CD19-Phycoerythrin (PE) marked cells (upper right panel), isolated CD19+ cells (lower left panel), and isolated CD3+ cells (lower right panel). (B) Figure showing the average of the WNT7A relative expression ratio ± Standard deviation (SD) obtained from the different groups. Normalization was performed by setting CP values of PBMC as 1 and taking GAPDH, RPL32, and RPS18 as reference genes. Experiments were carried out at least twice in all cases.

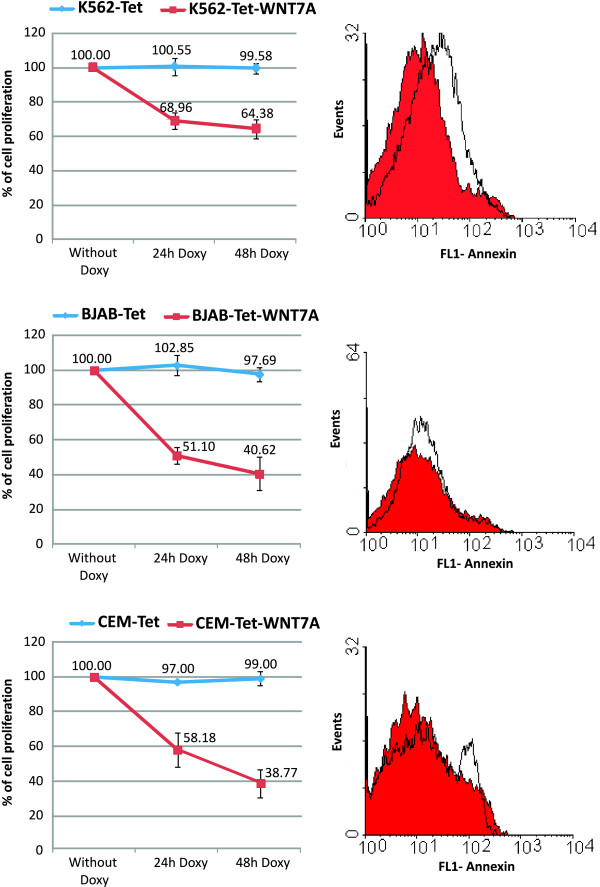

WNT7A expression is downregulated upon T-lymphocytes activation

Given that peripheral CD3+ (mature resting lymphocytes) express WNT7A, we asked whether the expression of this gene is related with their resting non-proliferative state. To elucidate this question, PBMC were induced to proliferate by addition of Phytohemagglutinin (PHA - 2 μg/mL), a lectin molecule that preferentially induces T-lymphocytes proliferation. After 48 hours of PHA-treatment, total RNA was isolated, retro-transcribed and analyzed by qRT-PCR. As can be observed in Figure 2A, WNT7A mRNA levels were drastically affected upon PHA activation, decreasing from 1 (non-activated resting PBMC, control cells) to 0.21 and 0.29 (relative expression ratio). Amplification curves and melting peaks obtained for WNT7A, RPL32, and RPS18 in non-treated PBMC and PHA-treated PBMC are depicted in Additional File 2.

Figure 2.

Relative expression of WNT7A in control cells and leukemia-derived cell lines. (A) Relative expression levels of WNT7A determined by qRT-PCR in resting and phytohemagglutinin-activated PBMC (activation was performed in PBMC from two volunteers and named TxPHA 1 and TxPHA 2). Values of the resting PBMCs (Control) of both volunteers were set as 1. (B) Relative expression levels of WNT7A determined by qRT-PCR in Jurkat, CEM, K562, HL60, and BJAB cell lines normalized to the healthy volunteers control group (setting as 1). In A, quantification was calculated using, Ribosomal Protein L32 (RPL32) and Ribosomal Protein S18 (RPS18) as reference genes. In B, quantification was calculated using additionally Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The graphics show means obtained with both reference genes and Standard deviations (SD). Experiments were carried out at least twice in duplicate.

Reduced WNT7A gene expression levels in leukemia-derived cell lines

Because WNT7A was expressed in resting peripheral T-lymphocytes, but severely reduced in activated T-lymphocytes, we assumed that leukemia-derived cell lines (which are undifferentiated and have a high grade of proliferation) should express low levels of this ligand. To test this hypothesis, we selected five different leukemia-derived cell lines: two of lymphoid origin (Jurkat and CEM); two of myeloid origin (K562 and HL60), and a lymphoma-derived B cell line (BJAB). We included also myeloid immature cell lines to determine whether this myeloid lineage indeed (as previously calculated by the analysis obtained from peripheral blood volunteer's samples) expresses very low levels of WNT7A. Therefore, we determined the quantitative expression of WNT7A by qRT-PCR assays. As a reference for comparison, we also included in this analysis a mix of cDNA obtained from total peripheral blood cells of five clinically healthy volunteers (control group). As can be observed in Figure 2B, relative expression utilizing GAPDH, RPL32, and RPS18 as reference genes exhibited very low expression levels of WNT7A in all leukemia-derived cell lines when compared with the control group. We observed relative values ranging from 0.026 in Jurkat cells to 0.002 in K562 cells when normalized to the control group (set as 1). After qRT-PCR assays, all amplified products were resolved in 1.5% agarose gels and visualized with Ultraviolet (UV) light for photo-documentation (data not shown).

In conclusion, the experiments performed previously allow us to demonstrate quantitatively that leukemia-derived cell lines of both myeloid and lymphoid origins express very low levels of WNT7A.

Peripheral blood cells of patients with leukemia also showed a significant decrease in WNT7A gene expression

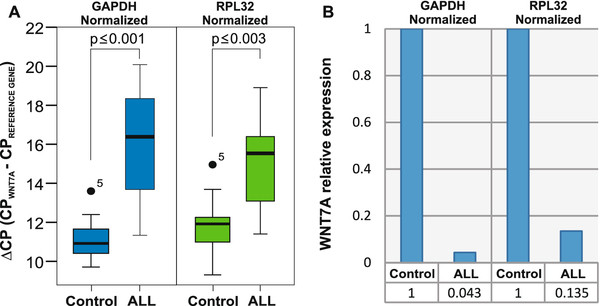

After demonstrating that WNT7A expression is strongly reduced in leukemia-derived cell lines, we wanted to determine whether WNT7A expression could also be diminished in blood samples of patients with leukemia in comparison with clinically healthy volunteers. With this aim, the expression of WNT7A was analyzed in 14 samples of patients with Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and in 19 samples of clinically healthy volunteers. We decided to determine the expression of WNT7A by normalizing to an internal reference gene; thus, the ΔCP was calculated, which represents a more absolute value. It is noteworthy that the ΔCP (CP of target gene - CP of reference gene) is inversely proportional to the expression of the target gene. Values of ΔCP of the analyzed groups (control and ALL) are represented in box plot graphics in Figure 3A. As can be observed in this figure, there is an evident difference between control values and those of patients with ALL normalized either with GAPDH (left panel) or with RPL32 (right panel). Higher ΔCP values were observed in the ALL group, which means lower expression of WNT7A. As shown in Figure 3A, when we compared the ALL group vs. the healthy volunteers group, we observed a statistical significance of p < 0.001 when normalized with GAPDH and p < 0.003 with RPL32. These results permit us to suggest that reduction of WNT7A expression could be a characteristic hallmark in patients with ALL.

Figure 3.

WNT7A expression in immature cells from patients with Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). (A) Box plot graphics showing ΔCP values taking GAPDH (left panel) or RPL32 (right panel) as reference genes. The graphics display median (dark lines), 25-75th percentile (boxes), interquartile ranges (whiskers), and outliers (small, dark circles) from 14 patients with ALL. Peripheral blood cells from 19 controls were included for comparison. Statistical significances are shown between both groups. (B) Graphic showing an average of the relative expression levels of WNT7A from the control and from the group with patients with ALL. The value obtained in the healthy volunteers control group was set as 1 and normalized either with GAPDH or RPL32 as reference genes.

Taking the median of the ΔCP values of controls and patients with ALL obtained with both reference genes, we calculated the average of WNT7A relative expression. As can be observed in Figure 3B, the average of WNT7A expression in patients in comparison to the control group (set as 1) diminished to 0.043 (GAPDH) or to 0.135 (RPL32).

In summary, there is a statistically significant decreased expression of WNT7A, not only in leukemia-derived cell lines in comparison with the control group, but also in patients with ALL when compared with healthy volunteers. Peripheral blood cells from four Acute myeloid leukemias (AML), three Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), and five Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) also revealed a tendency to exhibit reduced WNT7A expression when compared with the control group (data not shown).

Restoration of WNT7A inhibits cell growth in Jurkat cells

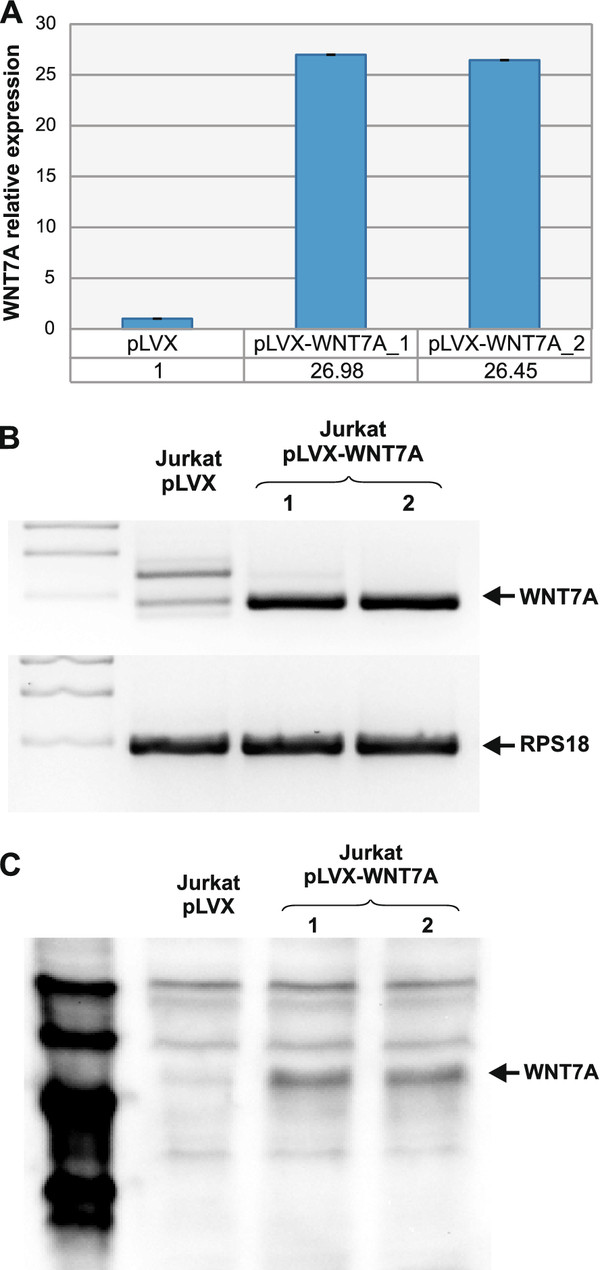

Because we found that WNT7A is expressed in CD3+ resting lymphocytes derived from healthy volunteers and not in immature leukemia-derived cells, it was in our interest to discern the biological effect of WNT7a restoration on leukemia cells. For this purpose, we used lymphoblastic Jurkat cells as model and overexpressed WNT7A employing a lentiviral system (pLVX-Puro or pLVX-WNT7A-Puro; a detailed description is provided in Materials and Methods). After 48 h of infection, cells were cultured with 1 μg/mL puromycin for selection of infected cells, and RNA and protein extraction were conducted on day 7 to corroborate WNT7A overexpression by qRT-PCR and Western blot assays (Figure 4). After this selection time, WNT7A relative expression was measured in the pLVX empty-vector infected cells and in the pLVX-WNT7A clone 1- and -2-infected cells. We named these cells clone 1 and clone 2 because we infected Jurkat cells with the viral particles containing pLVX-WNT7A-Puro in two independent experiments. As can be observed in Figure 4A, expression of WNT7A in pLVX-WNT7A infected cells was increased nearly 27-fold when compared to the pLVX-empty vector. The amplified products from the qRT-PCR assays were also electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gel as depicted in Figure 4B. Additionally, as can be observed in Figure 4C, WNT7A overexpression was also confirmed at protein levels.

Figure 4.

WNT7A overexpression in Jurkat cells. Overexpression of WNT7A in Jurkat cells using the lentiviral system was confirmed by qRT-PCR assays. (A) Graphic showing WNT7A relative expression taking GAPDH, RPL32 and RPS18 as constitutive genes in cells infected with pLVX (vector alone) or with pLVX-WNT7A. Infection was carried out in duplicate (pLVX-WNT7A clone 1 and 2). (B) Amplification products of WNT7A and RPS18 were run in 2.0% agarose gels and photodocumented. (C) Western blot assays (from 50 μg total protein) showing the presence of WNT7a protein only in pLVX-WNT7A-infected cells. The magic mark (2 μl) was used as protein marker.

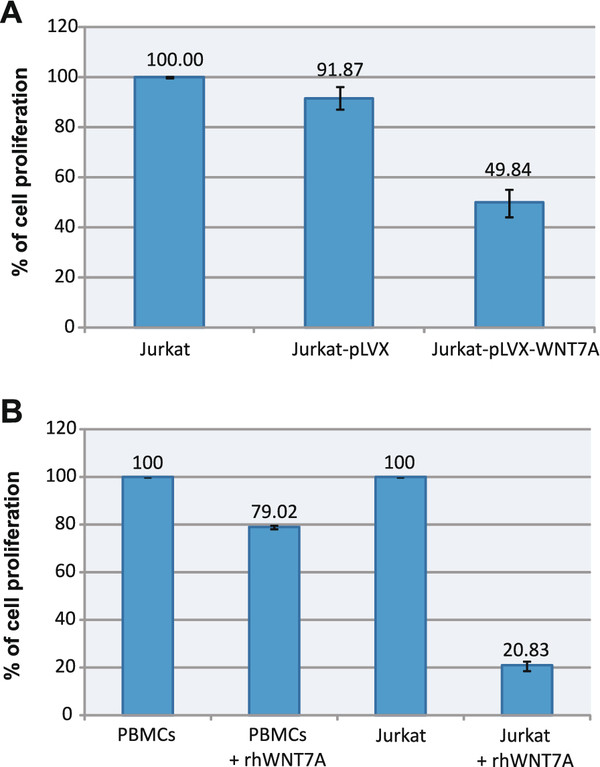

To determine the biological effect of WNT7A restoration in cell proliferation, after 2 weeks puromycin selection, we seeded in the same number (10,000) of Jurkat, Jurkat-pLVX, and Jurkat-pLVX-WNT7A cells in 96-well plates and measured the percentage of cell proliferation after a 48 h culture. Percentages of cell proliferation were obtained by taking the Optical density (OD) values of Jurkat cells as 100%. As illustrated in Figure 5A, we observed a decrease in the rate of cell proliferation of Jurkat-pLVX cells (91.87%), but a significantly lower decrease was observed in Jurkat-pLVX-WNT7A cells (49.84%). This observation allowed us to speculate that the WNT7A produced by Jurkat-infected cells could somehow inhibit cell proliferation. To discern this point, Jurkat cells and resting PBMC obtained from one of the healthy volunteers were incubated with 3 μg/mL of commercially recombinant human WNT7a for 48 h. As can be observed in Figure 5B, incubation of Jurkat cells with recombinant human WNT7a (rhWNT7a) reduced their growth drastically after 48 h (to 20.83%). In contrast, the PBMC exhibited only a small effect, even reaching 79.02% of growth at 48 h.

Figure 5.

WNT7A inhibits cell proliferation in Jurkat cells. (A) Percentage of cell proliferation measured in Jurkat cells, Jurkat-pLVX (stable transduced with empty-vector), or Jurkat-pLVX-WNT7A cells after 48 h of culture. Percentages of cell proliferation were obtained by taking Optical density (OD) values of the Jurkat cells as 100% cell proliferation. (B) Leukemia-derived Jurkat cells and PBMC were exposed for 48 h to 3 μg/mL of recombinant human WNT7a (+rhWNT7a). Afterward, the percentage of cell proliferation was measured by employing WST-1 and setting the value of non-treated control cells (Jurkat and PBMC for their respective assays) at 440 nm as 100% of cell proliferation.

Restoration of WNT7A does not induce the canonical β-catenin pathway in Jurkat cells

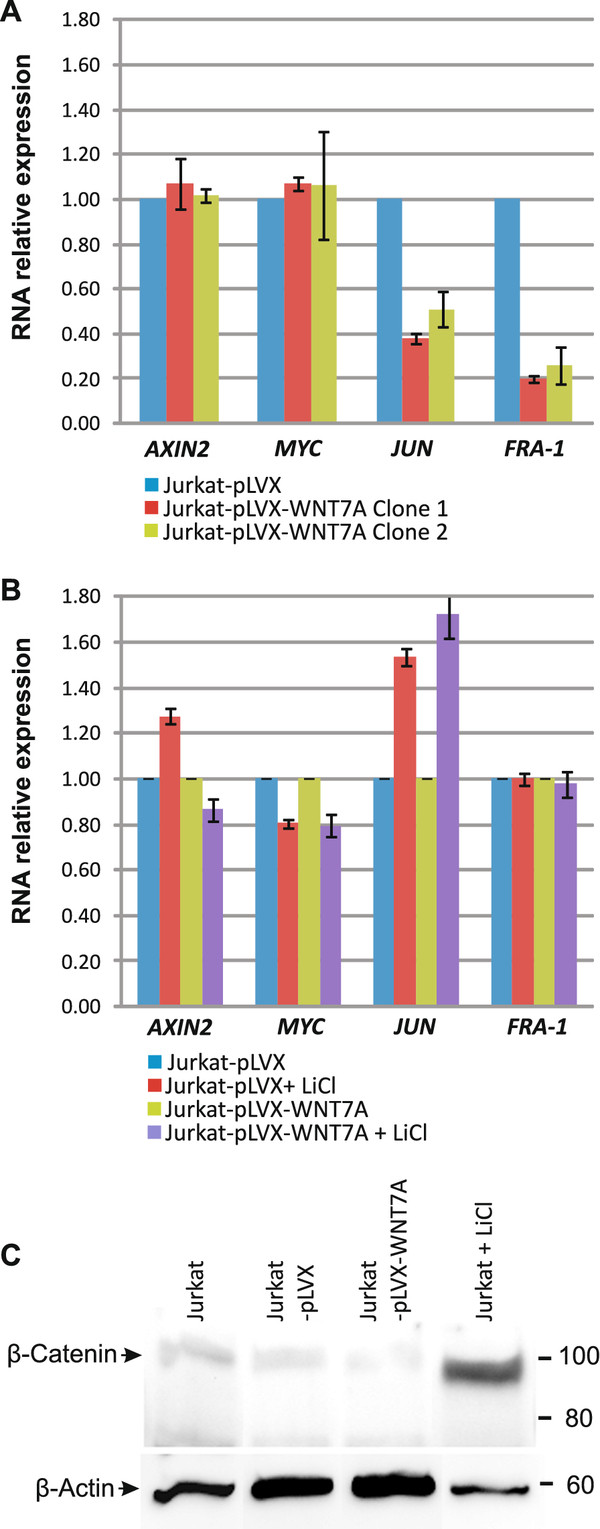

To determine whether the proliferation inhibition in Jurkat cells observed after WNT7a restoration was mediated by activation of the canonical β-catenin pathway, we analyzed the expression of putative target genes for this pathway by qRT-PCR assays. For this purpose, we determined the mRNA expression of AXIN2, MYC, JUN, and FRA-1 in Jurkat-pLVX- and Jurkat-pLVX-WNT7A-infected cells clone 1 and 2. As can be appreciated in Figure 6A, none of the aforementioned genes was activated by WNT7A restoration. Instead, decreased expression in JUN and FRA-1 was observed in clones expressing WNT7A. Interestingly, when we incubated cells with LiCl (0.01 M) for 20 h (it is known that LiCl activates Wnt signaling by inhibiting GSK3β, leading to β-catenin stabilization and translocation into the nucleus [25,26]), a restoration of the expression levels of JUN and FRA-1 was observed, which indicates that LiCl antagonize WNT7A activity in these cells (see Figure 6B). Additionally, to support that WNT7a in this model did not induce the canonical pathway, we performed Western blot assays to detect β-catenin in Jurkat, Jurkat-pLVX, and Jurkat-pLVX-WNT7A cells. As control, we also included LiCl-treated Jurkat cells. As expected, accumulation of β-catenin was only observed in the LiCl-treated cells and not in the WNT7A expressing cells (Figure 6C). These results clearly support the idea that the canonical pathway is not involved in the action of WNT7A on Jurkat cells.

Figure 6.

Restoration of WNT7A does not induce the canonical β-catenin pathway in Jurkat cells. (A) Relative expression levels of AXIN2, MYC, JUN, and FRA-1, determined by qRT-PCR in Jurkat-pLVX or Jurkat-pLVX-WNT7A clone-1 and -2 infected cells. Quantification was calculated by normalizing with Jurkat-pLVX (setting as 1) and utilizing GAPDH and RPL32 as reference genes. The graphic shows medians obtained with both reference genes ± Standard deviations (SD). (B) Relative expression levels of AXIN2, MYC, JUN, and FRA-1, determined by qRT-PCR in Jurkat-pLVX or Jurkat-pLVX-WNT7A clone-1 in the absence or presence of LiCl. Quantification was calculated by normalizing LiCl-treated cells with their corresponding Jurkat-pLVX or Jurkat-pLVX-WNT7A non-treated cells (setting each as 1) and utilizing GAPDH and RPL32 as reference genes. The graphic shows medians obtained with both reference genes ± SD. (C) Western blot analysis detecting β-catenin and β-actin in the presence or absence of LiCl and WNT7a.

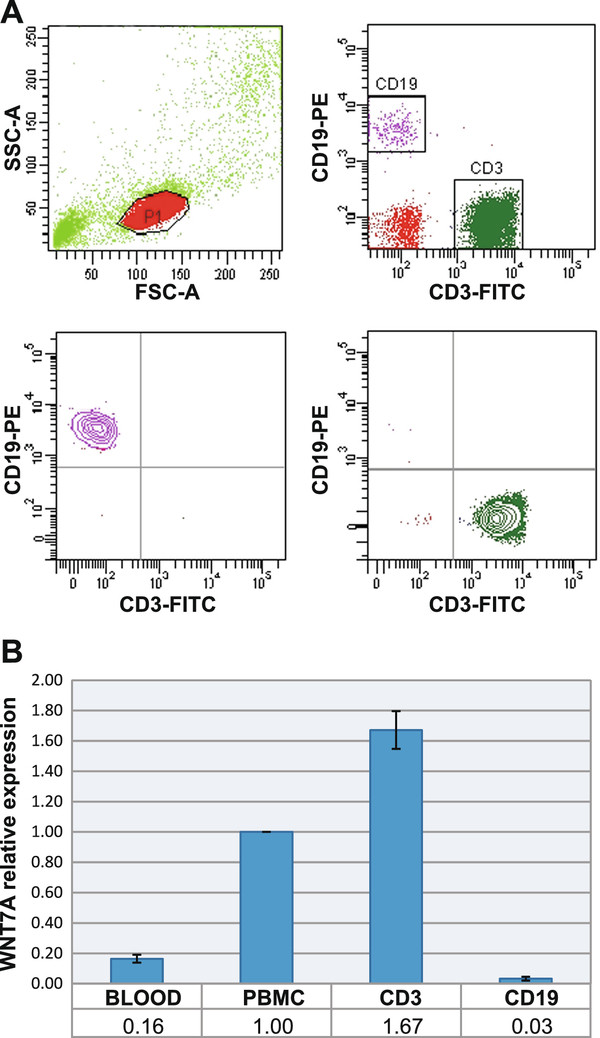

Restoration of WNT7A inhibits cell growth in K562, BJAB, and CEM cells

To confirm that restoration of WNT7A inhibits cell growth in leukemia-derived cells, we modified K562, BJAB, and CEM cells to overexpress WNT7A employing an inducible-lentiviral expression system (as described in Methods). We first obtained K562-, BJAB-, and CEM-Tet cells that contained only the regulator vector (Tet). Next, we obtained K562-, BJAB-, and CEM-Tet-WNT7A cells that should express WNT7A in the presence of doxycycline. To verify WNT7A overexpression, K562-, BJAB-, and CEM-Tet-WNT7A cells were grown in the absence or presence of doxycycline (750 ng/mL) for 4 h. Afterward, RNA extraction and retrotranscription were performed for the qRT-PCR assays. As can be observed in Figure 7A, expression of WNT7A indeed increased in all cell lines, rising 7.48 ± 1.19-fold in K562, 11.68 ± 0.77-fold in BJAB and 2.75 ± 0.59-fold in CEM. This induced overexpression was also confirmed at protein levels (after 48 h of doxycycline exposure) by Western blot analysis (see in Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

WNT7A overexpression in K562-, BJAB- and CEM-Tet-WNT7A cells. Overexpression of WNT7A in these cell lines using the doxycycline-inducible lentiviral expression system was confirmed by qRT-PCR and Western blot assays. (A) Graphics showing the amplification curves obtained for WNT7A and RPL32 in cells treated or not with Doxycycline (Doxy) for 4 h. The WNT7A normalized relative ratio of the cells treated with Doxy was calculated utilizing the non-treated cells as calibrator and taking GAPDH, RPL32 and RPS18 as reference genes in two independent experiments. (B) Western blot assays (from 50 μg total protein) showing the presence of WNT7a protein after a 38-h incubation with Doxy. Photo-documentation of the Coomassie stained gel is included as protein loading control.

Once we could establish that our inducible-WNT7A system was working adequately, we determined the WNT7A restoration effect on cell proliferation. For this purpose, we added WST-1 to the culture cells growing in the presence or absence of doxycycline after 24 and 48 h of incubation. Percentages of cell proliferation were obtained by taking the OD values of the cells growing in the absence of doxycycline as 100% of cell proliferation. As may be seen in Figure 8, WNT7A-inducible expression in all three cell lines decreased strongly, especially in BJAB-Tet-WNT7A and in CEM-Tet-WNT7A cells, decreasing to 40.62 and 38.77%, respectively, after 48 h of growth in the presence of doxycycline.

Figure 8.

Restoration of WNT7A in K562-, BJAB-, and CEM-Tet-WNT7A cells inhibits their cell proliferation. Graphs of the left column depict the percentage of cell proliferation measured in K562-, BJAB-, and CEM-Tet-WNT7A cells after 24-h and 48-h incubation with Doxycycline (Doxy). The empty-vector cell lines (K562-, BJAB-, and CEM-Tet) were also included as controls. The percentage of cell proliferation was measured by adding WST-1 to the cell cultures for 2 h and by reading the absorbance of treated and untreated cells at 440 nm. The value in each cell line of non-treated cells after 24 or 48 h was setting as 100% of cell proliferation. Right column graphs illustrate the histograms of the flow-cytometric analysis done for apoptosis detection utilizing Annexin-V-FLUOS as markers in non-treated (filled curve) and 48-h Doxy-treated cells (open curve). Ordinate: number of cells; Abscissa: fluorescence intensities.

Discussion

Wnt signaling is conserved from invertebrates to vertebrates and regulates early embryonic development, as well as the homeostasis of adult tissues; as a central pathway in both physiological processes, dysregulation of Wnt signaling is associated with many human diseases, and particularly with cancer [1]. Recently, Wnt signaling has also been implicated in hematopoiesis, both in self-renewal and in differentiation [1,10,18]. Based on these observations, it is hypothesized that dysregulation of the WNT pathway might contribute to the pathogenesis of lymphoproliferative diseases [12].

Despite the modest number of reports on the potential roles of Wnt signaling in leukemia, it is increasingly clear that Wnt signaling is dysregulated in several types of leukemia [12,18,27]. Some of these findings involve over- or underexpression of several Wnt ligands or Frizzled receptors [16,19,28,29], hypermethylation of natural WNT inhibitors [30], and overexpression of β-catenin [21].

Despite this knowledge, there are a very limited number of publications on the expression of WNT7A and its role in the biology of blood cells. One of the first observations of the implication of WNT7A in hematological disorders was the frequent deletion of the 3p25 chromosome band observed in patients with AML, CML, and ALL [31]. As is known, WNT7A is also localized at this chromosomal region [32,33] and its deletion could be an important step during the neoplastic transformation.

In this paper, we report the expression of WNT7A in normal peripheral T-lymphocytes and strongly reduced WNT7A expression, not only in leukemia-derived cell lines, but also in the peripheral blood cells of patients with leukemia.

We were able to demonstrate that T-lymphocytes, but not B-lymphocytes, express WNT7A (ΔCP 11.47 ± 1.2). In agreement with this observation, Lu et al. also found expression of this ligand in peripheral blood lymphocytes (ΔCP 11.81 ± 0.99), but do not determined that this expression was afforded mainly from T-cells [19]. In contrast, Sercan et al. found WNT7A expression in both T- and B-cells obtained from healthy volunteers [23]. Discrepancies in these data could be due to the different method employed for quantification. The previously mentioned research group quantified WNT7A expression by comparing the densities of amplified WNT7A and β-actin PCR products visualized on agarose gels, while our group did this by performing qRT-PCR assays, which afford very precise data for quantification analysis.

We found from 38- to 500-fold lower expression in leukemia-derived cell lines than in healthy control cells (see Figure 2B). These results are in agreement as reported recently by Sercan et al., in which they did not find WNT7A expression in leukemia-derived cell lines K562, HL60, Jurkat, and Namalwa [23]. However, the authors measured qualitatively, while we determined WNT7A expression quantitatively.

On the other hand, expression of WNT7A in hematological diseases has been only determined in patients with CLL and AML. Memarian et al. observed reduced expression of WNT7A in Iranian patients with AML compared with normal subjects [24]; however, the authors did not find this difference in patients with CLL [29]. It is noteworthy that in both of these previously mentioned reports, WNT7A expression was calculated using the band densities of WNT7A and β-actin after conventional PCR. In agreement with the results of Memarian et al. we also observed reduced expression of WNT7A also in patients with AML, but statistical significance was not reached, probably due to the low number of patients with AML whom we analyzed (data not shown). Regarding expression of this ligand in patients with CLL; Lu et al. also observed lower WNT7A expression in patients with CLL (ΔCP 15.43 ± 2.94) when compared with healthy peripheral blood lymphocytes (11.81 ± 0.99)[19]. In this sense, we also observed this behavior in 4 out of 5 CLL patients (ΔCP 16.3 ± 1.5). Despite this low number of CLL patients, we found a statistical significance of p ≤0.02 when compared with healthy control cells (ΔCP 11.47 ± 1.2) (data not shown).

Interestingly, when we analyzed peripheral blood cells from 14 patients with ALL, these also expressed reduced WNT7A expression (ΔCP 15.19 ± 2.5) and we found a statistically significant difference of p ≤0.001 (GAPDH) and p ≤0.003 (RPL32) when compared with the control group (Figure 3).

Another important observation that we discerned is that WNT7A decreases acutely after PHA activation. To our knowledge, this is the first report evidencing that lymphocytes require reduction of their WNT7A levels in order to proliferate and suggests that dysregulation in the expression of this ligand needs to occur during oncogenesis to lose control of cell proliferation. Interestingly, it has been reported that T-cell activation by phytohemagglutinin results in a strong increase of phosphorylated GSK3β [34], which in turn targets beta-catenin for ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation [35].

With respect to the reference genes used in the qRT-PCR assays, it is important to mention that there are no perfect reference genes for every treatment in every cell line. Thus, we used at least two reference genes in each assay and also evaluated some samples with a total of five reference genes (please see Additional Files 1 and 2). It has been determined that one of the reference genes that we used (RPS18) is useful as internal control for quantitative PCR in human lymphoblastoid cells, because constant levels of expression across the cell lines used were found following exposure to ionizing radiation as well as to PHA [36]. However, it could be that some, but not all, of the changes in WNT7A expression may be caused by changes in reference-gene expression when cells were treated with PHA.

To our knowledge, no other papers relating WNT7A and leukemia have been published; however, reduced or absent expression of WNT7A has also been observed in lung cancer when compared with normal lung and mortal, short-term bronchial epithelial culture by qRT-PCR assay [36,37].

Furthermore, it has been reported that WNT7a activates E-cadherin expression in lung cancer cells and that WNT7A loss may be important in lung cancer development or in progression due to its effects on E-cadherin, because E-cadherin in cancer has been associated with dedifferentiation, invasion, and metastasis [38]. In addition to the role of WNT7A observed in leukemia and lung cancer, disruptions or alterations of the WNT7A gene have also been found in oral premalignant lesions [39] and in esophageal squamous cells [40].

We were also able to demonstrate, in the Jurkat leukemia-derived cell line, that restoration of WNT7A (by lentiviral overexpression or the addition of human recombinant protein) inhibits cell proliferation (Figure 5). Moreover, with the inducible-lentiviral overexpression system, we also confirmed this observation in K562, BJAB, and CEM cells after WNT7a expression; however, induction of cell death was not observed (Figure 8). Spinsanti et al. also reported an anti-proliferative action of WNT7a expression in undifferentiated PC12 cells [41]. Additionally, recent studies have demonstrated that the combined expression of WNT7A and Frizzled 9 (Fzd9) in Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines inhibits transformed growth by activating ERK5 and increasing PPARgamma activity, representing a novel tumor suppressor pathway in lung cancer [36,42,43]. However, the biological role of WNT7A action in cancer is controversial at present; some evidence supports its activity as an oncogene, but there is also evidence of its tumor suppressor action [36,44,45]. This dual role can be explained by the FZD proteins that bind WNT7a. It has been reported that the binding of WTN7a and FZD5 induces the canonical pathway, which has been related with cancer development [46,47]. On the other hand, WTN7a can also bind FZD-10 and -9, which in turn activated the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathway (JNK). Activation of JNK has been shown to antagonize the canonical pathway [47].

Due to the reported dual behavior of WNT7A as a cell-proliferation inducer or blocker, it is reasonable to think that Jurkat cells preferentially express anti-proliferative FZD partners of WNT7A. To address this question, we analyzed the presence of FZD mRNAs in Jurkat cells compared with T-lymphocytes from healthy controls and found overexpression of FZD-3 and -6 and downmodulation of FZD-5 and -10 in Jurkat cells (data not shown). On analyzing hematopoietic cells and leukemia-derived cells, Sercan et al. also found expression of FZD-3 and -6 in leukemia-derived T-lymphocytes [23]. The presence of FZD-6 in lymphocytes is interesting, because it has been shown that FZD-6 can act as a negative regulator of the canonical pathway [48]. Whether FZD-6 can interact with WTN7a in lymphocytes and what the biological consequences of this interaction would be are questions that remain open.

It has been observed that increased expression of some WNT ligands such as WNT3a, induces activation of the canonical pathway, accompanied by an increase in the proliferation and survival of leukemia cells [49]. In addition, it has been reported that β-catenin comprises an integral part of AML cell proliferation and cell cycle progression [50]. Because we observed downmodulation of WNT7A in leukemia-derived cells, it appears that WNT7a in Jurkat cells does not activate the WNT/β-catenin pathway. Evidence that supports this notion is the finding that mRNA levels of the putative canonical target genes AXIN2, MYC, JUN, and FRA-1 were not increased after WNT7a restoration (see Figure 6). In contrast, mRNA from JUN and FRA-1 were strongly downregulated in WNT7A-expressing cells, but again restored (FRA-1) or even upregulated (JUN) when cells were treated with LiCl (Figures 6A &6B). Concerning this point, it has been reported that the β-catenin - T cell-factor/lymphoid-enhancer-factor complex directly interacts with the promoter region of JUN and FRA-1 [51]. Because we observed restoration of the expression levels of JUN and FRA-1 after LiCl treatment, it is very probable that LiCl antagonize WNT7a activity in these cells. An additional observation that supports the idea that WNT7a is working in this model in a non-canonical pathway is that expression of β-catenin was not increased after WNT7a restoration (as seen in Figure 6C).

Conclusions

In conclusion, we are demonstrating, by qRT-PCR analysis, that WNT7A is significantly reduced in leukemia-derived cell lines as well as in patients with leukemia when compared with clinically healthy volunteers. The finding that WNT7A restoration inhibits proliferation of leukemia-derived Jurkat cells, but not of PBMC, allows us to assume that WNT7A can be acting as a modulator of cell proliferation, especially in T-cells that are producing this protein. In this regard, impairment of this anti-proliferative function could be an important event in leukemia and in some cancer-cell types. If this is true, therapeutic tools directed toward restoring WNT7A expression in patients with leukemia might increase the probabilities of their overcoming this disease.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AAL wrote the paper and supervised all experiments performed as principal investigator; JARA and EBC recruited patients, collected samples, and isolated RNA; ABOH performed all qRT-PCR assays, Western blots, and PHA treatments, and aided in writing the manuscript; IDMC cloned, sequenced, and performed WNT7A overexpression with the Lentiviral system; BGC carried out the sorting assays, collaborated in the detection of WNT7a and contributed in the PHA treatments; MRS performed WNT7a overexpression with the inducible-Lentiviral system, conducted the assays with the recombinant protein, and performed growth inhibition analysis; MARR and PBN aided in writing and designing the protocol and also analyzed data; PCOL and GHF detected the apoptosis rate by FACS; AAL, LFJS, and ABC performed the statistical analysis, and AAL and LFJS conceived of and discussed the experimental work. All participants contributed commentary on and corrected the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Relative expression analysis comparison among five of the most used reference genes. A panel of five different reference genes was used to calculate WNT7A expression. Amplification curves of all genes are shown in BJAB cells treated or not with Doxycycline (+Doxy). Standard curves were performed to calculate error and efficiency in all genes used. Table show WNT7A relative expression normalized with the different reference genes.

Amplification curves obtained in cells treated or not with PHA. Upper panel graphics shown the Amplification curves obtained for WNT7A in non-treated PBMC and in PBMC treated for 48 h with PHA. Middle graphics correspond to RPS18 and bottom panel graphics to RPL32. Melting peaks are also shown in the right panels, which indicate the specificity of the PCR reaction.

Contributor Information

Alejandra B Ochoa-Hernández, Email: bereniceqfb@hotmail.com.

Moisés Ramos-Solano, Email: leboyfr@gmail.com.

Ivan D Meza-Canales, Email: idavidmc@hotmail.com.

Beatriz García-Castro, Email: gacas.bet@hotmail.com.

Mónica A Rosales-Reynoso, Email: mareynoso@hotmail.com.

Judith A Rosales-Aviña, Email: judithabisag1@gmail.com.

Esperanza Barrera-Chairez, Email: vivibarrera2010@hotmail.com.

Pablo C Ortíz-Lazareno, Email: paulcesar05@hotmail.com.

Georgina Hernández-Flores, Email: geodic1967@yahoo.com.mx.

Alejandro Bravo-Cuellar, Email: abravocster@gmail.com.

Luis F Jave-Suarez, Email: lfjave@yahoo.com.

Patricio Barros-Núñez, Email: pbarros_gdl@yahoo.com.mx.

Adriana Aguilar-Lemarroy, Email: adry.aguilar.lemarroy@gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

We thank our technicians María de Jesús Delgado and Leticia Ramos for their efficient support in the laboratory. We are grateful with Maggie Brunner and José David Ramos Solano for proofreading of the manuscript. ABOH is grateful for the scholarship obtained from CONACYT-Mexico. This work was supported by grants CONACYT-CB-2008-01-105705 and FIS/IMSS/PROT/G10/817 (both to AAL).

References

- Chen X, Yang J, Evans PM, Liu C. Wnt signaling: the good and the bad. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2008;40:577–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2008.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R, Fuerer C, Ching W, Harnish K, Logan C, Zeng A. et al. Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:59–66. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MD, Nusse R. Wnt signaling: multiple pathways, multiple receptors, and multiple transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22429–22433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JR. The Wnts. Genome Biol. 2002;3:REVIEWS3001. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-3-1-reviews3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van AR, Mikels A, Nusse R. Alternative wnt signaling is initiated by distinct receptors. Sci Signal. 2008;1:re9. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.135re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert K, Jones KA. Wnt signaling: is the party in the nucleus? Genes Dev. 2006;20:1394–1404. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuerer C, Nusse R, ten BD. Wnt signalling in development and disease. Max Delbruck Center for Molecular Medicine meeting on Wnt signaling in Development and Disease. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:134–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AW, Rattis FM, DiMascio LN, Congdon KL, Pazianos G, Zhao C. et al. Integration of Notch and Wnt signaling in hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:314–322. doi: 10.1038/ni1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T, Duncan AW, Ailles L, Domen J, Scherer DC, Willert K. et al. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:409–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groen RW, Oud ME, Schilder-Tol EJ, Overdijk MB. ten BD, Nusse R et a.: Illegitimate WNT pathway activation by beta-catenin mutation or autocrine stimulation in T-cell malignancies. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6969–6977. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongracz JE, Stockley RA. Wnt signalling in lung development and diseases. Respir Res. 2006;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeti R, Becker MW, Tian Q, Lee TL, Yan X, Liu R. et al. Dysregulated gene expression networks in human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3396–3401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900089106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia A, Roman-Gomez J, Cervera J, Such E, Barragan E, Bolufer P. et al. Wnt signaling pathway is epigenetically regulated by methylation of Wnt antagonists in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:1658–1666. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren MK, Dosen G, Hystad ME, Stubberud H, Funderud S, Rian E. Wnt3A activates canonical Wnt signalling in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) cells and inhibits the proliferation of B-ALL cell lines. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:400–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu QL, Zierold C, Ranheim EA. Dysregulation of Frizzled 6 is a critical component of B-cell leukemogenesis in a mouse model of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;113:3031–3039. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-163303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan NI, Bendall LJ. Role of WNT signaling in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:761–774. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D, Zhao Y, Tawatao R, Cottam HB, Sen M, Leoni LM. et al. Activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3118–3123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308648100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tickenbrock L, Hehn S, Sargin B, Choudhary C, Baumer N, Buerger H. et al. Activation of Wnt signalling in acute myeloid leukemia by induction of Frizzled-4. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:1215–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai YJ, Qiu LG, Li ZJ, Yu Z, Li CH, Wang YF. et al. The expression of beta-catenin and its significance in leukemia cells. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2007;28:541–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Wang X. Role of Wnt canonical pathway in hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sercan Z, Pehlivan M, Sercan HO. Expression profile of WNT, FZD and sFRP genes in human hematopoietic cells. Leuk Res. 2010;34:946–949. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memarian A, Jeddi TM, Vossough P, Sharifian RA, Rabbani H, Shokri F. Expression profile of Wnt molecules in leukemic cells from Iranian patients with acute myeloblastic leukemia. Iran J Immunol. 2007;4:145–154. doi: 10.22034/iji.2007.17191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao AS, Kremenevskaja N, Resch J, Brabant G. Lithium stimulates proliferation in cultured thyrocytes by activating Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;153:929–938. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AK, Yi H, Hayes SH, Seigel GM, Hackam AS. Lithium chloride regulates the proliferation of stem-like cells in retinoblastoma cell lines: a potential role for the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Mol Vis. 2010;16:36–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerkamp F, van Dongen JJ, Staal FJ. Notch and Wnt signaling in T-lymphocyte development and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:1197–1205. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin V, Valencia A, Agirre X, Cervera J, Jose-Eneriz ES, Vilas-Zornoza A. et al. Epigenetic regulation of the non-canonical Wnt pathway in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:425–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memarian A, Hojjat-Farsangi M, Asgarian-Omran H, Younesi V, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Sharifian RA. et al. Variation in WNT genes expression in different subtypes of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:2061–2070. doi: 10.3109/10428190903331082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Gomez J, Cordeu L, Agirre X, Jimenez-Velasco A, San Jose-Eneriz E, Garate L. et al. Epigenetic regulation of Wnt-signaling pathway in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:3462–3469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B, Billstrom R, Kristoffersson U, Akerman M, Garwicz S, Ahlgren T. et al. Deletion of chromosome arm 3p in hematologic malignancies. Leukemia. 1997;11:1207–1213. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui TD, Lako M, Lejeune S, Curtis AR, Strachan T, Lindsay S. et al. Isolation of a full-length human WNT7A gene implicated in limb development and cell transformation, and mapping to chromosome 3p25. Gene. 1997;189:25–29. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00808-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegawa S, Kumano Y, Okui K, Fujiwara T, Takahashi E, Nakamura Y. Isolation, characterization and chromosomal assignment of the human WNT7A gene. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;74:149–152. doi: 10.1159/000134404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendeckel U, Scholz B, Arndt M, Frank K, Spiess A, Chen H. et al. Inhibition of alanyl-aminopeptidase suppresses the activation-dependent induction of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK-3beta) in human T cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:62–65. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe C, Bienz M. Inhibition of GSK3 by Wnt signalling - two contrasting models. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3537–3544. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn RA, Marek L, Han SY, Rodriguez K, Rodriguez N, Hammond M. et al. Restoration of Wnt-7a expression reverses non-small cell lung cancer cellular transformation through frizzled-9-mediated growth inhibition and promotion of cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19625–19634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo R, West J, Franklin W, Erickson P, Bemis L, Li E. et al. Altered HOX and WNT7A expression in human lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12776–12781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohira T, Gemmill RM, Ferguson K, Kusy S, Roche J, Brambilla E. et al. WNT7a induces E-cadherin in lung cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10429–10434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734137100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui IF, Rosin MP, Zhang L, Ng RT, Lam WL. Multiple aberrations of chromosome 3p detected in oral premalignant lesions. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2008;1:424–429. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay I, Singh A, Phukan R, Purkayastha J, Kataki A, Mahanta J. et al. Genome-wide analysis of chromosomal alterations in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma exposed to tobacco and betel quid from high-risk area in India. Mutat Res. 2010;696:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinsanti P, De VT, Caruso A, Melchiorri D, Misasi R, Caricasole A. et al. Differential activation of the calcium/protein kinase C and the canonical beta-catenin pathway by Wnt1 and Wnt7a produces opposite effects on cell proliferation in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 2008;104:1588–1598. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn RA, Van SM, Hammond M, Rodriguez K, Crossno JT Jr, Heasley LE. et al. Antitumorigenic effect of Wnt 7a and Fzd 9 in non-small cell lung cancer cells is mediated through ERK-5-dependent activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26943–26950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennis MA, Van Scoyk MM, Freeman SV, Vandervest KM, Nemenoff RA, Winn RA. Sprouty-4 inhibits transformed cell growth, migration and invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and is regulated by Wnt7A through PPARgamma in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:833–843. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg D, Akerstrom G, Westin G. Mutational analyses of WNT7A and HDAC11 as candidate tumour suppressor genes in sporadic malignant pancreatic endocrine tumours. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:110–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirikoshi H, Katoh M. Expression of WNT7A in human normal tissues and cancer, and regulation of WNT7A and WNT7B in human cancer. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:895–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caricasole A, Ferraro T, Iacovelli L, Barletta E, Caruso A, Melchiorri D. et al. Functional characterization of WNT7A signaling in PC12 cells: interaction with A FZD5 x LRP6 receptor complex and modulation by Dickkopf proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37024–37031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmon KS, Loose DS. Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 regulates two Wnt7a signaling pathways and inhibits proliferation in endometrial cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1017–1028. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan T, Yaniv A, Bafico A, Liu G, Gazit A. The human Frizzled 6 (HFz6) acts as a negative regulator of the canonical Wnt. beta-catenin signaling cascade. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14879–14888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan NI, Bradstock KF, Bendall LJ. Activation of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway mediates growth and survival in B-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:338–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siapati EK, Papadaki M, Kozaou Z, Rouka E, Michali E, Savvidou I. et al. Proliferation and bone marrow engraftment of AML blasts is dependent on beta-catenin signalling. Br J Haematol. 2011;152:164–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann B, Gelos M, Siedow A, Hanski ML, Gratchev A, Ilyas M. et al. Target genes of beta-catenin-T cell-factor/lymphoid-enhancer-factor signaling in human colorectal carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1603–1608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Relative expression analysis comparison among five of the most used reference genes. A panel of five different reference genes was used to calculate WNT7A expression. Amplification curves of all genes are shown in BJAB cells treated or not with Doxycycline (+Doxy). Standard curves were performed to calculate error and efficiency in all genes used. Table show WNT7A relative expression normalized with the different reference genes.

Amplification curves obtained in cells treated or not with PHA. Upper panel graphics shown the Amplification curves obtained for WNT7A in non-treated PBMC and in PBMC treated for 48 h with PHA. Middle graphics correspond to RPS18 and bottom panel graphics to RPL32. Melting peaks are also shown in the right panels, which indicate the specificity of the PCR reaction.