Abstract

The acquisition of drug resistance to chemotherapy is a significant problem in the treatment of cancer, greatly increasing patient morbidity and mortality. Tumors are often sensitive to chemotherapy upon initial treatment, but repeated treatments can select for those cells that have were able to survive initial therapy and have acquired cellular mechanisms to enhance their resistance to subsequent chemotherapy treatment. Many cellular mechanisms of drug resistance have been identified, most of which result from changes in gene and protein expression. While changes at the transcriptional level have been duly noted, it is primarily the post-transcriptional processing of pre-mRNA into mature mRNA that regulates the composition of the proteome and it is the proteome that actually regulates the cell’s response to chemotherapeutic insult, inducing cell survival or death. During pre-mRNA processing, intronic non-protein-coding sequences are removed and protein-coding exons are spliced to form a continuous template for protein translation. Alternative splicing involves the differential inclusion or exclusion of exonic sequences into the mature transcript, generating different mRNA templates for protein production. This regulatory mechanism enables the potential to produce many different protein isoforms from the same gene. In this review I will explain the mechanism of alternative pre-mRNA splicing and look at some specific examples of how splicing factors, splicing factor kinases and alternative splicing of specific pre-mRNAs from genes have been shown to contribute to acquisition of the drug resistant phenotype.

1.0 Introduction

Surgery, radiation and chemotherapeutic drugs are the standard of care in cancer patients. These treatments are often used in combination to provide the highest efficacy, with surgical removal of solid tumor aiding in the debulking of as much tumor mass as possible. Radiation and chemotherapy act to further reduce the remaining tumor, inducing cell death in cancer cells by exploiting their rapid growth rate compared to most non-cancerous tissue. Combined, these three treatment modalities can act to reduce tumor burden, prolong patient survival, and in the best case scenario cure the patient. Chemical chemotherapy (referred to herein as chemotherapy or chemotherapeutics) has long been used to treat human malignancies and its effects have been useful in improving long term patient outcome, although usually at the expense of normal human tissue as well. Cancer cells usually have faster growth rates and higher energy requirements than their normal counterparts, developing faster cell cycle times and an increased need for DNA synthesis and passage through mitosis. Chemotherapeutics act by many different mechanisms, but most indiscriminately target the most rapidly growing cells in the body by directly damaging DNA, inhibiting key enzymes, affecting microtubule dynamics required for the entry or exit from mitosis, and binding to and inhibiting cell surface proteins, among others.

Initially, many tumors respond to chemotherapy and regress; however, some cancer cells may survive and expand, causing the cancer to come out of remission. This new population of cancer cells often has an increased resistance to cancer chemotherapy. Resistance is often seen upon repeated rounds of chemotherapy as the resistant population of cells is increasingly selected. Additionally, mutations can occur during the processes of tumor development or chemotherapy treatment that can greatly affect the therapeutic response. The increased genomic instability of cancer cells allows for better adaptation to a therapeutic insult. For those cells that have not already undergone genetic and proteomic changes to enhance their survival responses, the selective pressures brought about by chemotherapeutics can often cause upregulation of cellular mechanisms involved in chemotherapy resistance. The mechanisms by which cancer cells adapt or are selected for their chemotherapy resistance are numerous and vary within a cancer type and from patient to patient. Many of these mechanisms have been elegantly described elsewhere [1]. Mechanisms of resistance include increases in detoxifying exzymes, increases in cellular efflux of drugs, increases in DNA repair mechanisms, loss of tumor suppressor genes, and changes in the apoptotic response, among others. Although some mechanisms of resistance are more frequent in a given cancer type, the heterogeneity of tumors, even within a given tissue and subtype, make the understanding of these mechanisms and developing therapies to overcome them more difficult. Mechanisms of drug resistance within a tumor are often multifactorial, generating additional complexity to the problem of overcoming resistance. The era of personalized medicine will hopefully allow us to understand mechanisms of chemotherapy resistance in a given patient and develop novel therapies or make more creative use of existing therapies to overcome resistance.

It is generally accepted that many mechanisms of chemotherapy resistance involve mutations and altered expression of genes and proteins. The cellular proteome is the key factor in the cell’s response to chemotherapy and can be affected by many factors, including genetic mutations, gene transcription, mRNA processing, translation, protein modification and protein degradation. In particular, alternative splicing of pre-mRNA has a great influence on the cellular proteome by controlling the expression of particular isoform products from the same gene and producing proteins with altered, and often opposite, function. Alternative splicing is a normal cellular process that can be manipulated by a cancer cell to enhance survival in response to chemotherapeutic insult. In this review, I will focus on the alternative processing of transcribed pre-mRNA into mature mRNA and how this process regulates both protein function and contributes to resistance to cancer chemotherapy. I will also discuss specific examples of how alternative splicing has been shown to regulate the acquisition of chemoresistance by cancer cells.

2.0 Discussion

2.1 Alternative splicing generates proteome diversity

The regulation of gene and protein expression is a major determinate of cell biology and fate, controlling homeostasis and regulating how a cell responds to its extracellular environment. A cell constantly monitors its surroundings and responds to changes by regulating its gene expression. In humans, these signals can come from surrounding cells by diffusion or distant tissues and organs, carried to the cell by the vascular or lymphatic system. Extracellular cues can strongly influence how genes are expressed by sending intracellular signals through kinase cascades, G protein regulation, changes in redox, and cell-permeable factors such as hormones and xenobiotics. These extracellular signals stimulate signaling pathways can affect the splicing machinery, causing activation or inhibition of protein factors involved in splicing [2]. In particular, signaling from the ubiquitous Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) and Akt families of proteins has been shown to directly affect splicing factor action [3-7]. Much activity in the era of modern cancer research has involved identifying genes and proteins that are differentially expressed between normal cells and tissues and cancerous ones, and then determining the effect that this differential expression has on the cancerous phenotype. A plethora of genes have been discovered whose expression is either upregulated or downregulated in cancerous versus normal tissue and experimental analysis has given us insight into how these genes regulate the cancerous phenotype. One interesting phenomena of cancer cells is there ability to adapt to their environment to promote cell survival and proliferation under conditions where normal cells would undergo cell death. This is particularly important during metastasis, evasion of the immune system, and overcoming resistance to cancer chemotherapeutics.

The development of microarray and deep sequencing technology has enabled us to come to a closer understanding of how changes in extracellular cues lead to changes in gene expression. The mapping of the human genome has allowed us to identify approximately 25,000-30,000 distinct genes that code for proteins. While it is the genes contained within the DNA that provides the genetic code for life, it is the proteins that are eventually made from these genomic sequences that control the biology of the cells and tissues. The cellular proteome is in a constant state of flux with the generation of new proteins through protein synthesis and the degradation of proteins back into their elemental forms. By studying the proteome of cells and tissues, it became evident over the years that the number of proteins produced by the human genome far exceeds the number of genes, generating a new level of protein expression diversity. The question arose as to how more than one protein could come from a single gene. As science has progressed over the past several decades, it was discovered that genes contained both protein-coding and non-coding segments, with the relative size of the non-coding sequences far exceeding that part of the gene that actually coded for protein.

As a gene is transcribed by RNA polymerase II, an entire RNA copy of the gene is produced into what is called a pre-mRNA, which requires further processing to become a mature mRNA that codes for protein. Besides the 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions, which do not code for protein, the pre-mRNA contains exons, which code for protein, and intervening sequences, known as introns, that are be removed to make a mature mRNA. Additional processing includes addition of a 5’ 7-methylguanylate cap and the addition of the 3’ poly (A) tail, both of which serve to protect the mRNA from degradation by ribonucleases. The long sequences of pre-mRNA are spliced into mature mRNA to remove intronic sequences, leaving only the protein-encoding exons, the 5’ and 3’ untranslated sequences, the cap and the poly-A tail. Genes can have dozens of exons which must be spliced together to form the coding sequence for a protein, with intronic sequences that can be tens of thousands of base pairs long. When one thinks about the large sequences of intronic RNA that have to be efficiently cut out of the pre-mRNA and the assembly of sequential exons into the mature mRNA, whose codons fit together perfectly to encode a protein, one can see that the fidelity of this process is truly remarkable. It has been estimated that 90% of genes in the human genome contain more than one exon [8], requiring the removal of intronic sequences from the mature mRNA in order to code for a protein. While initially this seems like a complex method of generating an mRNA to code for a protein, it is in reality an ingenious way of generating protein diversity, obviating the need for multiple copies of the same gene to encode for similar, yet different proteins.

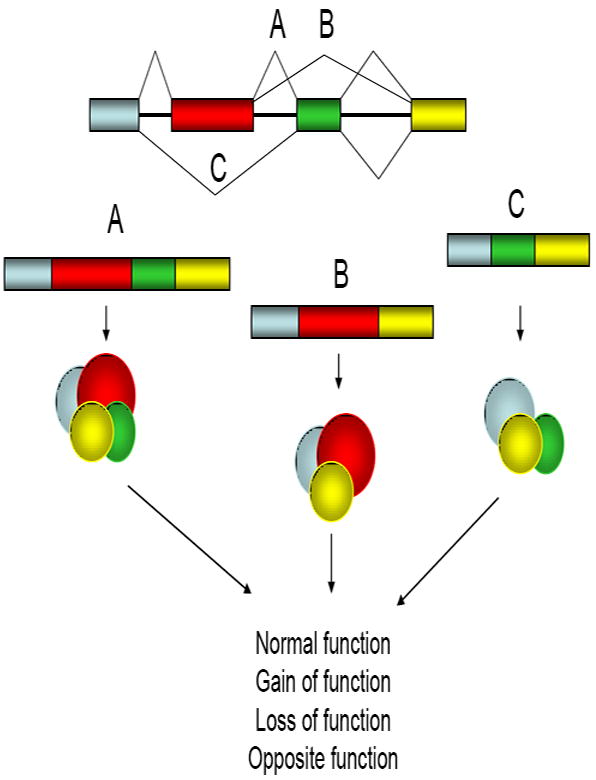

If each pre-mRNA from a gene was processed in the same way, to include all sequential exons in the mature mRNA, only one protein would be produced by each gene. This sequential splicing of each exon is known as constitutive splicing and occurs for many genes, coding for a full-length protein. The expression of more than one protein from a gene is regulated by the process of alternative pre-mRNA splicing, in which the exons from pre-mRNA of a transcribed gene are differentially spliced together to create a variety of mature mRNAs that encode for different forms of the same protein (Figure 1) [9]. Alternative splicing occurs when one or more exons are skipped, alternate 5’ or 3’ splice sites are utilized, introns are retained in the mature mRNA, or alternative promoters or polyadenylation sites are utilized. Alternative splicing is a normal means of post-transcriptional processing that allows for proteome diversity. Alternative exon inclusion into mature mRNA allows for proteins generated from the same gene to contain or exclude protein sequences or even entire protein domains, which can have a radical effect on protein function, generating gain of function, loss of function, or even to the extent of producing proteins with opposite function. Alternative splicing is thought to regulate between 60-74% of the human genome [10, 11], thereby greatly affecting protein diversity. The proteome of a normal cell or tissue can vary greatly from that of the same cell or tissue in the disease state, which can be accounted for by changes in gene expression, alternative pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA stability, and the synthesis and stability of proteins. It has been estimated that up to 50% of human genetic diseases arise from changes in alternative splicing [12, 13]. These changes in alternative splicing generate proteomic changes that contribute to the disease phenotype, including changes that occur in the development and maintenance of cancer. Alternative splicing can be particularly important in the process of acquired chemoresistance, as cells that have either already changed their splicing patterns are selected for or as cells adapt to the chemotherapeutic insult by the increased production of protein isoforms that enhance the cell’s ability to survive. In the remainder of this review, I will discuss the basic mechanics of how pre-mRNA splicing occurs, discuss how regulators of pre-mRNA splicing can affect chemoresistance, and discuss some specific examples of genes whose alternative splicing of pre-mRNA generates functionally different proteins that contribute to the development of resistance to cancer chemotherapeutics.

Figure 1.

Alternative splicing creates proteomic diversity to regulate protein function. Pre-mRNA consists of protein-coding entrons (colored bars) and non-coding introns (solid lines between bars). During the process of splicing, introns get removed by the splicesome complex to generate a coding mRNA. Each exon can be sequentially included in the final transcript (A) to generate a full length protein, or particular exons can be skipped to generate transcripts that are missing exons, generating proteins that are missing or certain sequences (B and C). The proteins that are produced from these alternatively spliced mRNA can have variations in their function due to the inclusion or exclusion of protein sequences and domains.

2.2 The spliceosome regulates pre-mRNA splicing

Pre-mRNA splicing into mature mRNA transcripts is carried out in a co-transcriptional manner in the nucleoplasm of the cell. The immature pre-mRNA is processed into mature mRNA by the spliceosome, a large protein complex consisting of small nuclear ribonuclear particles (snRNPs) and numerous accessory proteins that functions in the step-wise processing of pre-mRNA [13, 14]. Excellent reviews on the spliceosome and the intricacies of pre-mRNA splicing have been written [15]. The spliceosome complex assembles in a step-wise fashion at the 5’ and 3’ splice sites. snRNPs within the spliceosome are composed of both protein and small nuclear RNA molecules (snRNA), the latter of which are around 150 bases in length. There are five primary, highly conserved snRNA components of the spliceosome, termed U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6. These snRNAs recognize specific sequences in the pre-mRNAs that direct the spliceosome to the splice sites where splicing will occur. These sequences in the pre-mRNAs are located within the introns at the junctions between an intron and an exon. At the 5’ end of an intron is a GU dinucleotide that marks the 5’ splice site and is recognized by complementary sequences in the U1 snRNP. In the 3’ end of the introns there is a critical adenosine in a region known as the branch point site, followed by a polypyrimidine sequence. The U2 snRNP recognizes the branch site and binds to it through complementary sequences with aid from the U2 auxiliary factor (U2AF) protein. At the 3’ end of the intron is a conserved AG dinucleotide, which serves as a recognition point for the U2AF and some alternative splicing factor proteins.

The splicing removal of each intron occurs in a two step process involving SN2-like transesterification reactions [16]. In the first step, the 2’OH of the critical adenosine at the branch site attacks the 5’ splice site, allowing the cleaved mRNA intron to fold back on itself, aligning the sequences in the 5’ splice site with those of the branch site. The resulting folded-over confirmation of the intron is referred to as a lariat structure. In the second step of splicing, the 3’OH of the released 5’ exon attacks the 3’ splice site of the intron, effectively removing the 3’ end of the intron and fusing the 3’ end of the exon with the 5’ end of the following exon. The intron in between is released and eventually degraded. Regulatory sequences within the exons and introns, known as exonic and intronic splicing enhancers and silencers, can enhance or repress the selection of a particular splice site, guiding the spliceosome’s selection of individual sites of pre-mRNA splicing and regulating exon inclusion or exclusion into the mature mRNA [16, 17]. The spliceosome has intrinsic mechanisms of determining which splice sites in a pre-mRNA will be utilized, which can be influenced by other associated proteins [15]. The spliceosome is thought to contain over 150 proteins, some of which are involved in the constitutive splicing of pre-mRNA [18, 19]. The spliceosome is in a constant state of flux in terms of proteins and RNA, as the complex becomes assembled through a complicated series of steps at individual splice sites. Mass spectrometry has been highly useful to identify individual protein components of the spliceosome [18, 19]. Additional protein factors that aid in the selection of alternative splice sites and are called alternative splicing factors. Specific structures in the nucleus known as nuclear speckles act as a reservoir for inactive splicing factors that are not actively engaged in splicing [20], often obviating the requirement for new protein synthesis in order for pre-mRNA splicing to occur. The nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 has been shown to localize to speckles and to enhance the localization of splicing factors to the speckles, as well as influence splicing factor phosphorylation [21]. In effect, MALAT1 acts as a scaffold for the storage of inactive splicing factors in nuclear speckles.

Alternative mRNA splicing factors are proteins that help direct the spliceosome to recognize splice sites. There are two main classes of splicing factors; SR (serine-arginine-rich) proteins, which stimulate alternative splicing through alternative intron and exon recognition [14, 22, 23] and hnRNPs, (heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoproteins) which act as alternative splicing repressors [24]. SR proteins contain multiple Arginine/Serine repeats that are targets of multiple phosphorylations by SR protein kinases (SRPKs), particularly of the SRPK and CLK (Cdc2-like kinase) families [25-27]. Other kinases, including the signaling molecules Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAP kinases) can phosphorylate splicing factors and regulate their function [3, 28]. Phosphorylation of SR proteins by CLK and SRPK proteins has been shown to regulate their intranuclear localization, stimulating their release from nuclear speckles into the nucleoplasm where they associate with the spliceosome [27, 29]. Interestingly, it has been found that while phosphorylation of some splicing factors is required for spliceosome assembly, a dephosphorylation step is required for the catalytic step of splicing, as a splicing complex in vitro requires dephosphorylation by PP2A in order for splicing to occur [30, 31]. hnRNP molecules have also been shown to be regulated by phosphorylation. hnRNP A1, a negative regulator of splicing, has been shown to be phosphorylated by the p38 MAP kinase/Mnk1 pathway in response to cell stress, resulting in cytoplasmic accumulation of hnRNP A1 in stress granules and inhibiting its ability to regulate alternative splicing [5, 6]. Additional RNA binding proteins that do not fit into either the SR or hnRNP classes of proteins have can also act as alternative splicing factors [3, 32-34]. Regulation of alternative splicing site selection by splicing factors depends of their relative concentrations [35, 36] and differential expression of alternative splicing factors has been observed in cancer, with the potential to profoundly regulate the diversity of proteins that are expressed in a cancer cell versus a normal cell [37, 38].

2.3 Splicing factor 45 (SPF45)

One alternative splicing factor that has been shown to be involved in drug resistance is splicing factor 45 (SPF45), a 45 kDa nuclear protein [39, 40]. SPF45 was first identified in mammalian cells by mass spectrometry analysis of the spliceosome complex [18, 19]. SPF45 is involved in regulation of the second step of pre-mRNA splicing, regulating use of an AG dinucleotide in the 3’ alternative splice site in of pre-mRNA of the Sex lethal (Sxl) gene in Drosophila. SPF45 recognition of this site promotes the female-specific expression of the alternative splicing factor Sxl [41]. SPF45 is not a member of the SR protein or hnRNP families of splicing factors. SPF45 consists of an unstructured N-terminal domain, followed by an α-helical, 40 amino acid G-patch motif [42] involved in protein-protein [43] and protein-nucleic acid interactions [44, 45], and a C-terminal RRM (RNA-recognition motif). G patch and RRM domains are commonly found in proteins that regulate mRNA processing. The SPF45 RRM domain is homologous to RRMs in components of the U2 auxiliary factor (U2AF) and is required for mRNA splicing [41]. In humans, SPF45 is widely expressed in ductal epithelium, but is greatly increased in several forms of cancer, with the highest amounts in bladder, lung and colon, but with overexpression in breast, ovarian, pancreatic and prostate cancer as well [39]. For each of these tumor types, at least 72% of tumor samples analyzed had SPF45 overexpression compared to normal tissue. In agreement with the data on solid tumors, we have observed significant overexpression of SPF45 protein in primary ovarian cancer cells isolated from patient ascites and in ovarian cancer cell lines (Liu et al., submitted). There is currently no data identifying factors that regulate SPF45 expression in either normal or cancerous tissues, or if the overexpression of SPF45 is due to increased transcription. Overexpression could be a result of gene amplification, promoter demethylation, or increased activity of the transcription factors that regulate its expression,. Alternatively, protein half life could be increased in cancerous tissue. We have found that the protein kinase Clk1 enhances SPF45 stabilization by two-fold through regulation of a proteasome-dependent pathway (Liu et al, submitted).

A potential role for SPF45 in drug resistance was first noted by its identification by suppressive-subtractive PCR analysis as a gene upregulated in EMT6 mouse mammary cells and tumors selected for resistance to cyclophosphamide [39]. Forced overexpression of SPF45 in HeLa cells demonstrated a 4-7 fold increase in resistance to doxorubicin. Ectopic SPF45 expression in the A2780 ovarian cancer cell line induced a multidrug resistant phenotype, inducing 3-21 fold resistance to a variety of chemotherapeutics with differing mechanisms of action, including carboplatin, vinorelbine, doxorubicin, etoposide, mitoxantrone and vincristine, while knockdown of endogenous SPF45 in A2780 cells sensitized the cells to etoposide [40]. Co-treatment of SPF45 overexpressing A2780 cells with tamoxifen, an estrogen receptor antagonist, partially restored drug sensitivity to mitroxantrone, suggesting a role for estrogen receptors in SPF45 action and SPF45 was found to associate with estrogen receptor β. SPF45 must also exert its chemoprotective effects through ER-dependent and - independent mechanisms, as tamoxifen only partially reversed SPF45-mediated drug resistance and other drugs were not tested for their cooperation with tamoxifen. The mechanism of SPF45 induction of drug resistance is unknown, but is not believed to be through an increase in drug efflux, as SPF45-overexpressing cells accumulated similar amounts of doxorubicin as compared to vector control cells [40]. One of the few known mammalian splicing targets of SPF45 is fas pre-mRNA [34], encoding a pro-apoptotic transmembrane receptor, inducing exon 6 skipping in fas pre-mRNA, generating a soluble, dominant-negative Fas protein [34, 46].

As stated above, phosphorylation of splicing factors regulates their intranuclear localization and splice site utilization [47]. Using a mutant Extracellular Regulated Kinase 2 (ERK2) engineered to uniquely utilize an analog of ATP [48], N6-cyclopentyl-ATP, we have identified SPF45 as a novel co-immunoprecipitating ERK2 substrate (Al-Ayoubi, et al., submitted). We also found that SPF45 is phosphorylated by the p38 and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) MAP kinases, making it the first splicing factor to our knowledge that is regulated by more than one MAP kinase. We have identified extracellular stimuli that induce phosphorylation of SPF45 in each MAP kinase pathway specific manner. Enhancement of ERK2 signaling decreased SPF45 alternative splicing of exon 6 of fas pre-mRNA in a minigene assay in cells. Interestingly, SPF45 overexpression in SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cells decreased ErbB2 gene and protein expression, dependent on intact ERK2 phosphorylation sites on SPF45. This downregulation of ErbB2 expression resulted in slower growth of SPF45 overexpressing cells compared to vector controls. It is currently unknown whether the downregulation of ErbB2 expression, correlating with a reduced growth rate, affects chemoresistance, but since chemotherapy often has its strongest effects on the fastest growing cells, it is plausible that the slower growth rate of the cells could influence the apoptotic effect of chemotherapeutic agents. Indeed, indolent ovarian tumors often have a poor response to chemotherapy.

We have also found that stable SPF45 overexpression in SKOV-3 cells induces four-fold enhancement of fibronectin 1 expression and enhances inclusion of the EDA region into fibronectin transcripts, in both an ERK phosphorylation independent and dependent manner, respectively (Al-Ayoubi et al., submitted). The EDA region of fibronectin is expressed in cellular fibronectin, as opposed to plasma fibronection, and its inclusion is enhanced in embryonic and migratory cells and tissues [49]. A common characteristic of ovarian cancer is the formation of intraperitoneal ascites containing multicellular spheroids of cancer cells. Multicellular spheroids have intrinsically higher mechanisms of drug resistance compared to the same cells grown in monolayer [50] and fibronectin and beta-1 integrins, the cellular receptors for fibronectin, are important in the formation of multicellular spheroids in ovarian cancer cell lines [51]. Transforming growth factor beta stimulates a number of genes involved in the fibrotic response, including fibronectin, and upregulation of these genes has been shown to increase the compactness of ovarian cancer multicellular spheroids [52]. Therefore, SPF45 overexpression and subsequent upregulation of fibronectin could enhance multicellular spheroid formation, enhancing the drug resistant phenotype in vivo. In addition, we have shown that Clk1 phosphorylates SPF45 on multiple serine residues, regulating SPF45 alternative splice site utilization and intranuclear localization (Liu et al., submitted). Collectively, these results demonstrate that while enhanced expression of a splicing factor in cancer cells can regulate chemoresistance, the phosphorylation of a splicing factor by cellular kinases can strongly influence its ability to regulate alternative splicing.

Interestingly, in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, the SPF45 homolog DRT111 has been demonstrated to play a role in DNA repair [53]. In addition SPF45 has recently been shown to influence DNA repair in Drosophilia, associating with RAD201, a member of the RecA/RAD51 family [54] and human SPF45 was recently shown to bind to Holliday junctions, an intermediate DNA structure involved in homologous recombination [55]. The involvement of SPF45 in both alternative mRNA splicing and DNA repair could help explain the multidrug resistant phenotype displayed upon SPF45 overexpression [39, 40] in respone to drugs with differing mechanisms of action, including DNA damaging agents.

2.4 SR protein kinase 1 (SRPK1)

As stated above, SR protein kinases phosphorylate SR splicing factors in arginine-serine rich domains in the carboxy terminus, regulating splicing factor localization in the nucleus and their ability to regulate splice-site selection [22]. With the ability of these kinases to phosphorylate many different splicing factors, they are of interest in the study of cancer pathology and chemotherapeutic resistance. One such kinase is SRPK1, which is ubiquitously expressed in normal tissues, with highest expression in the testis [56]. SRPK1 is overexpressed in ductal epithelial cells in pancreatic carcinoma, infiltrating breast carcinoma and colon tumors [57]. Targeted knockdown of SRPK1 with siRNA in MiaPaCa2 and Panc1 pancreatic carcinoma cells induces apoptosis [58], suggesting that SRPK1 expression alone is sufficient to enhance pancreatic cancer cell survival. Decreased SRPK1 expression was correlated with a decrease in SR protein phosphorylation and an induction of the pro-apoptotic Bax protein. Inoperable pancreatic tumors are primarily treated with gemcitabine, either alone or in combination with cisplatin. Importantly, SRPK1 knockdown enhanced pancreatic cancer cell death in response to either gemcitabine or cisplatin, both alone and in combination. These results demonstrate that regulation of splicing factor phosphorylation by SRPKs can affect not only cancer cell survival, but also regulate the cellular response to chemotherapeutic agents.

2.5 The androgen receptor

Prostate cancer is driven in large part by the androgen receptor, a 112 kDa steroid hormone binding receptor that binds to androgens and acts as a ligand-activated transcription factor. Like other receptors in its class, the androgen receptor (AR) consists of an N-terminal transactivation domain (TAD), a DNA binding domain (DBD) characterized by two zinc finger motifs, a hinge region, and a C-terminal ligand binding domain (LBD). In unstimulated cells, the AR resides in the cytoplasm bound to heat shock protein 90 (HSP90). Upon binding to androgens, such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone, the AR translocates to the nucleus as a consequence of its bipartite nuclear localization signal [59] and acts as a transcription factor.

Initially, prostate cancer is an androgen dependent disease that involves ligand/receptor activated transcriptional complexes driving cell proliferation. Current initial treatments for prostate cancer include attempting to disrupt the action of this receptor ligand complex by androgen ablation therapy. Androgen ablation therapy is carried out through physical castration, chemical castration to interfere with leutinizing hormone releasing hormone or gonadotropin releasing hormone, or through the use of AR antagonists such as bicalutamide. In advanced disease, androgen ablation therapy is unsuccessful due to the development of androgen independence, the mechanisms of which are under intense investigation. Several mechanisms have been proposed for the reduced requirement for androgen as well as for the ineffectiveness of AR antagonists in advanced prostate cancer. Bakin et al. [60] have demonstrated that constitutive signaling from Ras to MAP kinases causes hypersensitization of LNCaP prostate cancer cells to androgens, promoting cell proliferation at significantly lower levels of androgen compared to cells in which Ras is not hyperactivated. In addition, this same group demonstrated that inhibition of Ras signaling in androgen-refractory C4-2 prostate cancer cells restored androgen sensitivity [61]. Ras is not often mutated in prostate cancer, but signaling pathways that stimulate Ras activation are often upregulated in prostate cancer, resulting in enhanced ERK activation in prostate tumors, correlating with increased Gleason score and tumor stage [62]. The AR is a phosphoprotein [63] and its shuttling in and out of the nucleus and transcriptional activity is controlled by cellular stress induction of p38 MAP kinase [64].

Recent studies have identified alternative splice variants of the AR in prostate cancer that lack the LBD, making them unresponsive to androgens and, in some cases, allowing for constitutive activation of the receptor as a ligand-independent transcription factor. Several alternatively spliced variants of the AR have been identified (reviewed by Dehm et al. [65]), one of which appears to have particular clinical relevance and will be discussed here. A 75-80 kDa form of the AR was first identified in 22Rv1 cells was shown to contain the AR TAD but lack the LBD [66]. Unlike wild type AR, which is cytoplasmic in the absence of hormone, this mutant was found to be constitutively nuclear, have the capacity to bind to DNA in an androgen-independent manner [66] and to be more frequently expressed in prostate cancer samples than in normal prostate [67]. Initially, this AR isoform was proposed to be the result of proteolytic cleavage of the full length protein by calpain-2 [67]. However, Dehm et al [68] demonstrated that while siRNA targeting exon 1 inhibited expression of all AR isoforms in 22Rv1 cells, siRNA directed at exon 7 removed the 112 kDa form, but did not inhibit expression of the 75-80 kDa form and demonstrated that this isoform arose from alternative splicing. Moreover, it was found that this 75-80 kDa form of the AR could induce expression of AR responsive genes and cell growth in an androgen-independent manner. Further analysis of AR mRNA has identified several other splice variants than arise due to cryptic exons within introns 2 and 3. Exons 2 and 3 encode the zinc fingers for the DBD [65]. AR proteins that arise from these alternatively spliced mRNAs are constitutively active and can support AR cell functions in a ligand-independent manner [65, 68-71]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that alternative splicing of AR pre-mRNA can generate a constitutively active, ligand-independent receptor that could contribute to androgen-independent prostate cancer by obviating the requirement for androgen and preventing negative regulation of prostate cancer growth by AR antagonists.

2.6 STAT2

Interferon (IFN) has both pro-survival and antiproliferative affects on cells via regulation of intracellular signaling pathways and changes in gene transcription. Interferon is used as adjuvant therapy to treat several forms of cancer, including multiple myeloma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-hodgkins lymphoma, and melanoma [72-75]; however, tumors often become refractory to IFN treatment. Interferon signals through the NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa B) pathway for cell survival and the JAK (Janus kinase)/STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) pathway for cell death [76]. Upon activation by tyrosine phosphorylation, STAT family members dimerize and translocate to the nucleus, where they bind to DNA and act as transcription factors. Additional phosphorylation of STATs by MAP kinases at a conserved site in the transactivation domain enhances their ability to activate transcription [77]. To study acquired resistance to IFN therapy, Du et al. [78] selected IFN resistant cells through prolonged exposure to IFN in culture, as would occur with prolonged treatment in patients undergoing IFN therapy. An IFN resistant clone, RST2, derived from the Daudi cell line, was selected and shown to have increased resistance to staurosporine, campothecin and doxorubicin. In the case of IFN stimulation, STAT2 dimerizes with STAT1 and this complex associates with IRF9 (IFN regulatory factor 9) to activate transcription of genes containing an ISRE, (IFN stimulated response element). RST2 cells were shown to have a defect in STAT2 protein expression, but not mRNA expression. Further analysis demonstrated that STAT2 pre-mRNA in these cells underwent alternative splicing between exons 19 and 20 of STAT2, generating a stop codon before the Src homology 2 domain, a region required for dimerization with other STAT molecules after tyrosine phosphorylation. A previous report described a STAT2 alternatively spliced form generated by reading through the intron between exons 20 and 21, generating a stop codon in the SH2 domain [79]. Premature termination due to alternative splicing generates a STAT2 protein that cannot dimerize and is less stable than full length STAT2. Overexpression of a full length STAT2 cDNA in these cells restored IFN responses and sensitivity to chemotherapeutics, demonstrating that alternative splicing of STAT2 was responsible for the defects in IFN responses and chemotherapy resistance in RST2 cells.

2.7 Cyclin D1

Cyclin D1 is a cell cycle regulatory protein that is important for cell cycle progression through the G1 phase and its expression is induced in response to growth factor stimulation of cells. Cyclin D1 associates with CDK4 and CDK6 to form active kinase complexes that help drive cell proliferation through the phosphorylation and inactivation of the Rb tumor suppressor protein. Additionally, Cyclin D1 has been shown to stimulate transactivation of genes by the estrogen receptor [80-82]. Cyclin D1 overexpression has been seen in a number of tumor types and is particularly important in breast cancer [83-86]. Cyclin D1 is encoded by 5 exons, with exon 5 encoding Thr 286, a phosphorylation site important in protein export from the nucleus and protein stability [87, 88], although degradation of free cyclin D1 (i.e. not bound to a Cdk) does not require this phosphorylation [89]. Mutation of Thr286, preventing phosphorylation at this site, enhances cyclin D1 transforming ability in NIH-3T3 cells [87]. A splice variant of cyclin D1, cyclin D1b, is produced from an alternatively spliced mRNA that lacks exon 5 and contains sequences from intron 4 [90, 91]. Residues derived from this intronic sequence do not appear to affect protein function [92]. This alternative splice site is generated by a G870A polymorphism at the splice donor site, which along with Cyclin D1b expression, has been correlated with susceptibility and poor outcome in several forms of cancer, including breast cancer [93-102]. Recent data suggests that ASF/SF2 and Sam68 splicing factors regulate splicing of cyclin D1b transcripts in prostate cancer cells [103, 104]. Due to the loss of exon 5, Cyclin D1b is a constitutively nuclear protein that retains the ability to bind to CDK4, but is a poor inducer of Rb phosphorylation by its associated CDK4 [92, 105, 106]. The enhanced nuclear localization, decreased degradation, and lack of the ability to induce Rb phosphorylation likely contribute to the observation that cyclin D1b has increased ability to transform cells compared with cyclin D1 [105, 106].

DNA damage induces cyclin D1 degradation through regulation of motifs in the N-terminus that are common to both cyclin D1 and cyclinD1b [107]. Wang et al. [92] recently showed that endogenous cyclin D1, but not cyclinD1b, demonstrated increased degradation upon cisplatin treatment of MCF-7 breast cancer cells, although cyclin D1b overexpression alone was not observed to influence cisplatin sensitivity. Addition of the estrogen receptor antagonists 4-hydroxy tamoxifen or ICI 182780 induced cyclin D1 mRNA and protein degradation, accompanied by cyclinD1b mRNA degradation, but surprisingly enhanced cyclin D1b protein levels [92]. Moreover, overexpression of cyclin D1b, but not cyclin D1, conferred partial resistance to the growth inhibition induced by these estrogen receptor antagonists. Growth inhibition by estrogen receptor antagonists has been shown to be dependent upon p27Kip1 induction [108], but cyclin D1b overexpressing cells had a blunted p27Kip1 induction in response to estrogen receptor antagonists compared to cyclin D1 or GFP expressing cells [92]. These affects of cyclin D1b were dependent on its interaction with CDK4 and not upon estrogen receptor transactivation, as cyclin D1b lacks the LXXL motif required for interaction with the estrogen receptor and did not induce estrogen receptor transactivation [92]. Therefore, the acquisition of resistance of breast tumors to estrogen receptor antagonists could be via induction of cyclin D1b protein levels and the resulting affects on abrogation of cell cycle events normally accompanying estrogen receptor antagonist treatment.

2.8 c-FLIP

Some chemotherapeutics have been shown to activate cell death by initiation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway, which involves activation of death receptors. Such death receptors of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family of proteins induce apoptosis upon binding to their ligands. Activation of the TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) receptors as well as Fas, the receptor for Fas ligand (FasL), stimulate assembly of a death-inducing signal complex (DISC) by recruiting the adapter protein FADD (Fas-associated death domain) to the receptor, which then recruits the extrinsic apoptosis initiator procaspase 8 (also known as FLICE), stimulating caspase 8 cleavage and activation. The activation of procaspase 8 is an important step in the activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. c-FLIP (cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein) is a regulator of FADD recruitment of procaspase 8 to and activation at DISCs [109-112], regulating the apoptotic response [113, 114]. The cFLIP gene contains 14 exons that cover 52 kilobases [115]. Several alternatively spliced mRNAs for c-FLIP have been identified, but only three have been shown to code for proteins. The three forms of c-FLIP are known as the 55 kDa c-FLIPL, the 26 kDa c-FLIPS, and the 24 kDa c-FLIPR [116]. All three forms contain two death effector domains (DEDs) that are required for their localization to DISCs and allow them to affect caspase 8 recruitment. c-FLIPL contains an inactive caspase-like domain in its c-terminus, encoded by exons 8-14. c-FLIPS and c-FLIPR lack exon 1 and most of the C-terminus of c-FLIPL, including the caspase-like domain [115]. c-FLIPS contains exon 7, not present in c-FLIPL, which contains a stop codon, causing premature termination of the protein. c-FLIPR is similar to c-FLIPS, but retains intronic sequences after exon 5 that encode a stop codon. T cell receptor activation of thymocytes stimulates expression of c-FLIPS and c-FLIPR, whereas c-FLIPL is constitutively expressed in these cells [117, 118]. In addition to its direct role in caspase 8 regulation, c-FLIPL overexpression has been shown to inhibit p38 MAPK and NF-κB activation in some systems [119, 120], but has also been shown to activate ERK and NF-κB in T cells and promote proliferation [121, 122]. c-FLIPL has been implicated in both cell survival [113] and the induction of apoptosis [114] in response to TRAIL. These opposing observations may be explained by the level of c-FLIPL expression. Fricker et al. [123] recently demonstrated that intermediate amounts of c-FLIPL actually induce procaspase 8 cleavage and activation, stimulating the apoptotic pathway. At higher concentrations, c-FLIPL inhibits procaspase 8 activation. c-FLIPL overexpression also may inhibit the ubiquitin proteosome system [124].

c-FLIPL is overexpressed in colorectal adenocarcinoma [125] and may, therefore, contribute to carcinogenesis by inhibiting activation of caspase 8 and the extrinsic cell death pathway. Colon cancer has long been treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), a prodrug that is cytotoxic by virtue of its conversion to 5-fluorouridine-5’-triphosphoate and 5’fluoro-2’deoxyuridine-5’trifosfato, which become misincorporated into DNA and RNA, respectively. It can also be converted to fluoro-deoxyuridine monophosphate (FdUMP) and inhibit thymidylate synthase, disrupting the pool of nucleotides [126]. More recently, 5-FU has been used in combination with the topoisomerase-1 inhibitor irinotecan and the DNA-damaging agent oxaliplatin [127, 128]. 5-FU has been shown to induce DNA strand breaks in the human SW620 colon adenocarinoma cell line [129]. Longley et al. [130] tested the effect of inhibition of c-FLIP isoforms on the response of p53 wild type, mutant and null colon cancer cells to 5-FU, oxaliplatin and irinotecan. Combined siRNA-mediated knockdown of both c-FLIPL and c-FLIPS sensitized cells to chemotherapy in a p53-independent manner, but individual knockdown demonstrated that only siRNA to c-FLIPL, but not c-FLIPS, sensitized cells. Moreover, overexpression of c-FLIPL, but not c-FLIPS, protected HCT116p53+/+ cells from apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic treatment. Wilson et al. [131] also demonstrated that siRNA targeting both c-FLIPL and c-FLIPS induced apoptosis in several colon cancer cell lines, independent of p53 status. Xenografts of HCT116 colon cancer cells overexpressing c-FLIPL, but not c-FLIPS, decreased spontaneous and chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in cells. c-FLIPL overexpressing xenografts grew more rapidly than controls, a difference that was increased in the presence of 5-FU and oxaliplatin. Collectively, these results demonstrate that c-FLIPL has enhanced anti-chemotherapeutic effect in colon cancer cells and tumors compared to c-FLIPS through the prevention of apoptosis through the extrinsic pathway. The observed overexpression of c-FLIPL in colon cancers suggests that therapies specifically targeting c-FLIPL would enhance the clinical response to chemotherapeutic treatment of colon cancer.

3.0 Concluding remarks

Many other instances of alternative splicing of genes have been demonstrated to regulate chemoresistance, many more than could be covered in this review. Indeed, many of the proteins involved in the regulation of the apoptotic response in cells are generated by alternative splicing. One of the master regulators of the cellular response to chemotherapeutics is p53, which acts as a transcription factor that regulates the expression of many genes involved in cell cycle arrest and senescence as well as genes involved in DNA repair. The closely-related p63 and p73 genes share similar functions, but can also antagonize p53 action. Several differentially spliced isoforms of all three genes have been discovered. The role of p53, p63, and p73 genes and their splice variants in modulating chemoresistance in cancer cells and tissues was the topic of an excellent recent review by Muller et al. [132] and was, therefore, not covered here. Other proteins that regulate the apoptotic response are also regulated by alternative splicing and have been shown to be involved in chemoresistance. In particular, members of the Bcl2 family contain splice variants with opposite functions, with either anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic functions [133]. One such Bcl2 family member is the Bcl-x gene, which has two alternatively spliced isoforms, the anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL and the pro-apoptotic Bcl-xS. Specifically, Bcl-xL has been shown to be upregulated in cancer and to increase cellular resistance to a number of chemotherapeutic agents [134]. The Bcl2 family member Mcl-1 also is expressed in a long and short form, with the long form having an anti-apoptotic function and being overexpressed in cancer cells, while the short form plays an antagonistic role [135].

Changes in the ratio of alternative spliced products can be brought about by a number of factors within the cell during the process of tumorigenesis and the acquisition of chemoresistance. It is well known that many genetic changes occur in cancer cells that give them increased proliferation, metastatic and survival properties, as well as other characteristics that give them enhanced ability to survive and adapt. One of the key mechanisms of adaptation that is important for the long-term care of cancer patients is the ability of cancer cells to overcome the selective pressures brought about by chemotherapeutics. The increase in genomic instability in cancer cells contributes to their ability to adapt to selective pressures through the acquisition of mutations that give them a selective advantage, allowing for their reduced response to chemotherapeutics. Of course these mutations can not only affect the process of pre-mRNA splicing, including splice site selection, mutation of splice site recognition nucleotides, and expression of components of the splicing machinery, but many other factors as well, including genetic mutations that result in gain or loss of function mutations in proteins. These can be particularly important when DNA damaging agents are used in chemotherapy. Mutations acquired during therapeutic treatment can enhance the resistance of cells to the chemotherapeutic used. Cell line models of chemotherapeutic resistance are often generated by prolonged, low dose treatment of cells with a drug to study the acquisition of mutations and changes in the cellular proteome. A significant selected advantage can be gained by a small fold change in drug resistance due to the fact that the maximal tolerated doses of chemotherapy limit the effective concentrations of drugs that a cancer patient can receive.

The acquisition of chemotherapy resistance will continue to be a major hurdle to overcome in the successful treatment of every form of cancer and continued research in this area will require the development of novel therapies. With the recognition of the role of alternative splicing in regulating the apoptotic response to chemotherapy, researchers are working on novel ways to regulate how the cell regulates alternative splicing of key genes. Splice-switching oligonucletides are oligos designed to bind to pre-mRNA and prevent splice site utilization at the binding site. These molecules are being developed as chemotherapeutics to target alternative splicing of specific genes to regulate the protein isoform that will be produced. A number of genes have been targeted for alternative splicing reprogramming in order to enhance the efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutics [136, 137]. The further development of such compounds for the directed regulation of alternative splicing will hopefully prove beneficial to the treatment of chemoresistant tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant 1R01CA131200 to STE.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fodale V, Pierobon M, Liotta L, Petricoin E. Mechanism of cell adaptation: when and how do cancer cells develop chemoresistance? Cancer J. 2011;17:89–95. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318212dd3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heyd F, Lynch KW. Degrade, move, regroup: signaling control of splicing proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 36:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matter N, Herrlich P, Konig H. Signal-dependent regulation of splicing via phosphorylation of Sam68. Nature. 2002;420:691–5. doi: 10.1038/nature01153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shultz JC, Goehe RW, Wijesinghe DS, Murudkar C, Hawkins AJ, Shay JW, et al. Alternative splicing of caspase 9 is modulated by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway via phosphorylation of SRp30a. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9185–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guil S, Long JC, Caceres JF. hnRNP A1 relocalization to the stress granules reflects a role in the stress response. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5744–58. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00224-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Houven van Oordt W, Diaz-Meco MT, Lozano J, Krainer AR, Moscat J, Caceres JF. The MKK(3/6)-p38-signaling cascade alters the subcellular distribution of hnRNP A1 and modulates alternative splicing regulation. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:307–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allemand E, Guil S, Myers M, Moscat J, Caceres JF, Krainer AR. Regulation of heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 transport by phosphorylation in cells stressed by osmotic shock. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3605–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409889102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, et al. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456:470–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blencowe BJ. Alternative splicing: new insights from global analyses. Cell. 2006;126:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Modrek B, Resch A, Grasso C, Lee C. Genome-wide detection of alternative splicing in expressed sequences of human genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2850–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing Y. Genomic analysis of RNA alternative splicing in cancers. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4034–41. doi: 10.2741/2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matlin AJ, Clark F, Smith CW. Understanding alternative splicing: towards a cellular code. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:386–98. doi: 10.1038/nrm1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Will CL, Luhrmann R. Spliceosomal UsnRNP biogenesis, structure and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:290–301. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hastings ML, Krainer AR. Pre-mRNA splicing in the new millennium. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:302–9. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valadkhan S, Jaladat Y. The spliceosomal proteome: at the heart of the largest cellular ribonucleoprotein machine. Proteomics. 2010;10:4128–41. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwerk C, Schulze-Osthoff K. Regulation of apoptosis by alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2005;19:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neubauer G, King A, Rappsilber J, Calvio C, Watson M, Ajuh P, et al. Mass spectrometry and EST-database searching allows characterization of the multi-protein spliceosome complex. Nat Genet. 1998;20:46–50. doi: 10.1038/1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rappsilber J, Ryder U, Lamond AI, Mann M. Large-scale proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome. Genome Res. 2002;12:1231–45. doi: 10.1101/gr.473902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spector DL, Lamond AI. Nuclear speckles. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tripathi V, Ellis JD, Shen Z, Song DY, Pan Q, Watt AT, et al. The nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2010;39:925–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manley JL, Tacke R. SR proteins and splicing control. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1569–79. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graveley BR. Sorting out the complexity of SR protein functions. Rna. 2000;6:1197–211. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayeda A, Munroe SH, Caceres JF, Krainer AR. Function of conserved domains of hnRNP A1 and other hnRNP A/B proteins. Embo J. 1994;13:5483–95. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma CT, Velazquez-Dones A, Hagopian JC, Ghosh G, Fu XD, Adams JA. Ordered multi-site phosphorylation of the splicing factor ASF/SF2 by SRPK1. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duncan PI, Stojdl DF, Marius RM, Bell JC. In vivo regulation of alternative pre-mRNA splicing by the Clk1 protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5996–6001. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colwill K, Pawson T, Andrews B, Prasad J, Manley JL, Bell JC, et al. The Clk/Sty protein kinase phosphorylates SR splicing factors and regulates their intranuclear distribution. Embo J. 1996;15:265–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goehe RW, Shultz JC, Murudkar C, Usanovic S, Lamour NF, Massey DH, et al. hnRNP L regulates the tumorigenic capacity of lung cancer xenografts in mice via caspase-9 pre-mRNA processing. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3923–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI43552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misteli T, Caceres JF, Clement JQ, Krainer AR, Wilkinson MF, Spector DL. Serine phosphorylation of SR proteins is required for their recruitment to sites of transcription in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:297–307. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mermoud JE, Cohen P, Lamond AI. Ser/Thr-specific protein phosphatases are required for both catalytic steps of pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5263–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.20.5263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin S, Xiao R, Sun P, Xu X, Fu XD. Dephosphorylation-dependent sorting of SR splicing factors during mRNP maturation. Mol Cell. 2005;20:413–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai MC, Kuo HW, Chang WC, Tarn WY. A novel splicing regulator shares a nuclear import pathway with SR proteins. Embo J. 2003;22:1359–69. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stickeler E, Fraser SD, Honig A, Chen AL, Berget SM, Cooper TA. The RNA binding protein YB-1 binds A/C-rich exon enhancers and stimulates splicing of the CD44 alternative exon v4. Embo J. 2001;20:3821–30. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.14.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corsini L, Bonna S, Basquin J, Hothorn M, Scheffzek K, Valcarcel J, et al. U2AF-homology motif interactions are required for alternative splicing regulation by SPF45. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1038/nsmb1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caceres JF, Misteli T, Screaton GR, Spector DL, Krainer AR. Role of the modular domains of SR proteins in subnuclear localization and alternative splicing specificity. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:225–38. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanamura A, Caceres JF, Mayeda A, Franza BR, Jr, Krainer AR. Regulated tissue-specific expression of antagonistic pre-mRNA splicing factors. Rna. 1998;4:430–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grosso AR, Gomes AQ, Barbosa-Morais NL, Caldeira S, Thorne NP, Grech G, et al. Tissue-specific splicing factor gene expression signatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4823–32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grosso AR, Martins S, Carmo-Fonseca M. The emerging role of splicing factors in cancer. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1087–93. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sampath J, Long PR, Shepard RL, Xia X, Devanarayan V, Sandusky GE, et al. Human SPF45, a splicing factor, has limited expression in normal tissues, is overexpressed in many tumors, and can confer a multidrug-resistant phenotype to cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1781–90. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63538-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perry WL, 3rd, Shepard RL, Sampath J, Yaden B, Chin WW, Iversen PW, et al. Human splicing factor SPF45 (RBM17) confers broad multidrug resistance to anticancer drugs when overexpressed--a phenotype partially reversed by selective estrogen receptor modulators. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6593–600. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lallena MJ, Chalmers KJ, Llamazares S, Lamond AI, Valcarcel J. Splicing regulation at the second catalytic step by Sex-lethal involves 3’ splice site recognition by SPF45. Cell. 2002;109:285–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aravind L, Koonin EV. G-patch: a new conserved domain in eukaryotic RNA-processing proteins and type D retroviral polyproteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:342–4. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silverman EJ, Maeda A, Wei J, Smith P, Beggs JD, Lin RJ. Interaction between a G-patch protein and a spliceosomal DEXD/H-box ATPase that is critical for splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10101–10. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10101-10110.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Svec M, Bauerova H, Pichova I, Konvalinka J, Strisovsky K. Proteinases of betaretroviruses bind single-stranded nucleic acids through a novel interaction module, the G-patch. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:271–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frenal K, Callebaut I, Wecker K, Prochnicka-Chalufour A, Dendouga N, Zinn-Justin S, et al. Structural and functional characterization of the TgDRE multidomain protein, a DNA repair enzyme from Toxoplasma gondii. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4867–74. doi: 10.1021/bi051948e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Izquierdo JM, Majos N, Bonnal S, Martinez C, Castelo R, Guigo R, et al. Regulation of Fas alternative splicing by antagonistic effects of TIA-1 and PTB on exon definition. Mol Cell. 2005;19:475–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stamm S. Regulation of alternative splicing by reversible protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1223–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eblen ST, Kumar NV, Shah K, Henderson MJ, Watts CK, Shokat KM, et al. Identification of novel ERK2 substrates through use of an engineered kinase and ATP analogs. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14926–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blaustein M, Pelisch F, Srebrow A. Signals, pathways and splicing regulation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:2031–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desoize B, Jardillier J. Multicellular resistance: a paradigm for clinical resistance? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;36:193–207. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Casey RC, Burleson KM, Skubitz KM, Pambuccian SE, Oegema TR, Jr, Ruff LE, et al. Beta 1-integrins regulate the formation and adhesion of ovarian carcinoma multicellular spheroids. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:2071–80. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sodek KL, Ringuette MJ, Brown TJ. Compact spheroid formation by ovarian cancer cells is associated with contractile behavior and an invasive phenotype. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2060–70. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pang Q, Hays JB, Rajagopal I. Two cDNAs from the plant Arabidopsis thaliana that partially restore recombination proficiency and DNA-damage resistance to E. coli mutants lacking recombination-intermediate-resolution activities. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1647–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.7.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chaouki AS, Salz HK. Drosophila SPF45: A Bifunctional Protein with Roles in Both Splicing and DNA Repair. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Horikoshi N, Morozumi Y, Takaku M, Takizawa Y, Kurumizaka H. Holliday junction-binding activity of human SPF45. Genes Cells. 2010;15:373–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Papoutsopoulou S, Nikolakaki E, Chalepakis G, Kruft V, Chevaillier P, Giannakouros T. SR protein-specific kinase 1 is highly expressed in testis and phosphorylates protamine 1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2972–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.14.2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayes GM, Carrigan PE, Miller LJ. Serine-arginine protein kinase 1 overexpression is associated with tumorigenic imbalance in mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in breast, colonic, and pancreatic carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2072–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayes GM, Carrigan PE, Beck AM, Miller LJ. Targeting the RNA splicing machinery as a novel treatment strategy for pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3819–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou ZX, Sar M, Simental JA, Lane MV, Wilson EM. A ligand-dependent bipartite nuclear targeting signal in the human androgen receptor Requirement for the DNA-binding domain and modulation by NH2-terminal and carboxyl-terminal sequences. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13115–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bakin RE, Gioeli D, Sikes RA, Bissonette EA, Weber MJ. Constitutive activation of the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway promotes androgen hypersensitivity in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1981–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bakin RE, Gioeli D, Bissonette EA, Weber MJ. Attenuation of Ras signaling restores androgen sensitivity to hormone-refractory C4-2 prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1975–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gioeli D, Mandell JW, Petroni GR, Frierson HF, Jr, Weber MJ. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase associated with prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 1999;59:279–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gioeli D, Ficarro SB, Kwiek JJ, Aaronson D, Hancock M, Catling AD, et al. Androgen receptor phosphorylation Regulation and identification of the phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29304–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204131200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gioeli D, Black BE, Gordon V, Spencer A, Kesler CT, Eblen ST, et al. Stress Kinase Signaling Regulates Androgen Receptor Phosphorylation, Transcription, and Localization. Mol Endocrinol. 2005 doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dehm S, Tindall DJ. Alternatively spliced androgen receptor variants. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tepper CG, Boucher DL, Ryan PE, Ma AH, Xia L, Lee LF, et al. Characterization of a novel androgen receptor mutation in a relapsed CWR22 prostate cancer xenograft and cell line. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6606–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Libertini SJ, Tepper CG, Rodriguez V, Asmuth DM, Kung HJ, Mudryj M. Evidence for calpain-mediated androgen receptor cleavage as a mechanism for androgen independence. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9001–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dehm SM, Schmidt LJ, Heemers HV, Vessella RL, Tindall DJ. Splicing of a novel androgen receptor exon generates a constitutively active androgen receptor that mediates prostate cancer therapy resistance. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5469–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hu R, Dunn TA, Wei S, Isharwal S, Veltri RW, Humphreys E, et al. Ligand-independent androgen receptor variants derived from splicing of cryptic exons signify hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:16–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hu R, Isaacs WB, Luo J. A snapshot of the expression signature of androgen receptor splicing variants and their distinctive transcriptional activities. Prostate. 2011;71:1656–67. doi: 10.1002/pros.21382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marcias G, Erdmann E, Lapouge G, Siebert C, Barthelemy P, Duclos B, et al. Identification of novel truncated androgen receptor (AR) mutants including unreported pre-mRNA splicing variants in the 22Rv1 hormone-refractory prostate cancer (PCa) cell line. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:74–80. doi: 10.1002/humu.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grander D. How does interferon-alpha exert its antitumour activity in multiple myeloma? Acta Oncol. 2000;39:801–5. doi: 10.1080/028418600750063532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tan BR, Bartlett NL. Treatment advances in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2000;1:451–66. doi: 10.1517/14656566.1.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nicholas C, Lesinski GB. Immunomodulatory cytokines as therapeutic agents for melanoma. Immunotherapy. 3:673–90. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kirkwood J. Cancer immunotherapy: the interferon-alpha experience. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:18–26. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.33078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gough DJ, Levy DE, Johnstone RW, Clarke CJ. IFNgamma signaling-does it mean JAK-STAT? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:383–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.David M, Petricoin E, 3rd, Benjamin C, Pine R, Weber MJ, Larner AC. Requirement for MAP kinase (ERK2) activity in interferon alpha- and interferon beta-stimulated gene expression through STAT proteins. Science. 1995;269:1721–3. doi: 10.1126/science.7569900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Du Z, Fan M, Kim JG, Eckerle D, Lothstein L, Wei L, et al. Interferon-resistant Daudi cell line with a Stat2 defect is resistant to apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27808–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.028324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sugiyama T, Nishio Y, Kishimoto T, Akira S. Identification of alternative splicing form of Stat2. FEBS Lett. 1996;381:191–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zwijsen RM, Wientjens E, Klompmaker R, van der Sman J, Bernards R, Michalides RJ. CDK-independent activation of estrogen receptor by cyclin D1. Cell. 1997;88:405–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81879-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Neuman E, Ladha MH, Lin N, Upton TM, Miller SJ, DiRenzo J, et al. Cyclin D1 stimulation of estrogen receptor transcriptional activity independent of cdk4. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5338–47. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zwijsen RM, Buckle RS, Hijmans EM, Loomans CJ, Bernards R. Ligand-independent recruitment of steroid receptor coactivators to estrogen receptor by cyclin D1. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3488–98. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arnold A, Papanikolaou A. Cyclin D1 in breast cancer pathogenesis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4215–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Diehl JA. Cycling to cancer with cyclin D1. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:226–31. doi: 10.4161/cbt.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bartkova J, Lukas J, Muller H, Lutzhoft D, Strauss M, Bartek J. Cyclin D1 protein expression and function in human breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:353–61. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bartkova J, Lukas J, Strauss M, Bartek J. The PRAD-1/cyclin D1 oncogene product accumulates aberrantly in a subset of colorectal carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:568–73. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alt JR, Cleveland JL, Hannink M, Diehl JA. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of cyclin D1 nuclear export and cyclin D1-dependent cellular transformation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3102–14. doi: 10.1101/gad.854900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Diehl JA, Cheng M, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta regulates cyclin D1 proteolysis and subcellular localization. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3499–511. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Germain D, Russell A, Thompson A, Hendley J. Ubiquitination of free cyclin D1 is independent of phosphorylation on threonine 286. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12074–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Betticher DC, Thatcher N, Altermatt HJ, Hoban P, Ryder WD, Heighway J. Alternate splicing produces a novel cyclin D1 transcript. Oncogene. 1995;11:1005–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hosokawa Y, Gadd M, Smith AP, Koerner FC, Schmidt EV, Arnold A. Cyclin D1 (PRAD1) alternative transcript b: full-length cDNA cloning and expression in breast cancers. Cancer Lett. 1997;113:123–30. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)04605-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang Y, Dean JL, Millar EK, Tran TH, McNeil CM, Burd CJ, et al. Cyclin D1b is aberrantly regulated in response to therapeutic challenge and promotes resistance to estrogen antagonists. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5628–38. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Knudsen KE, Diehl JA, Haiman CA, Knudsen ES. Cyclin D1: polymorphism, aberrant splicing and cancer risk. Oncogene. 2006;25:1620–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abramson VG, Troxel AB, Feldman M, Mies C, Wang Y, Sherman L, et al. Cyclin D1b in human breast carcinoma and coexpression with cyclin D1a is associated with poor outcome. Anticancer Res. 30:1279–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Millar EK, Dean JL, McNeil CM, O’Toole SA, Henshall SM, Tran T, et al. Cyclin D1b protein expression in breast cancer is independent of cyclin D1a and associated with poor disease outcome. Oncogene. 2009;28:1812–20. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Burd CJ, Petre CE, Morey LM, Wang Y, Revelo MP, Haiman CA, et al. Cyclin D1b variant influences prostate cancer growth through aberrant androgen receptor regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2190–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506281103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Izzo JG, Malhotra U, Wu TT, Ensor J, Babenko IM, Swisher SG, et al. Impact of cyclin D1 A870G polymorphism in esophageal adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:S11–5. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rydzanicz M, Golusinski P, Mielcarek-Kuchta D, Golusinski W, Szyfter K. Cyclin D1 gene (CCND1) polymorphism and the risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:43–8. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-0957-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ito M, Habuchi T, Watanabe J, Higashi S, Nishiyama H, Wang L, et al. Polymorphism within the cyclin D1 gene is associated with an increased risk of carcinoma in situ in patients with superficial bladder cancer. Urology. 2004;64:74–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Le Marchand L, Seifried A, Lum-Jones A, Donlon T, Wilkens LR. Association of the cyclin D1 A870G polymorphism with advanced colorectal cancer. Jama. 2003;290:2843–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.21.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang YJ, Chen SY, Chen CJ, Santella RM. Polymorphisms in cyclin D1 gene and hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2002;33:125–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Matthias C, Branigan K, Jahnke V, Leder K, Haas J, Heighway J, et al. Polymorphism within the cyclin D1 gene is associated with prognosis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2411–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Olshavsky NA, Comstock CE, Schiewer MJ, Augello MA, Hyslop T, Sette C, et al. Identification of ASF/SF2 as a critical, allele-specific effector of the cyclin D1b oncogene. Cancer Res. 70:3975–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Paronetto MP, Cappellari M, Busa R, Pedrotti S, Vitali R, Comstock C, et al. Alternative splicing of the cyclin D1 proto-oncogene is regulated by the RNA-binding protein Sam68. Cancer Res. 70:229–39. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lu F, Gladden AB, Diehl JA. An alternatively spliced cyclin D1 isoform, cyclin D1b, is a nuclear oncogene. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7056–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Solomon DA, Wang Y, Fox SR, Lambeck TC, Giesting S, Lan Z, et al. Cyclin D1 splice variants Differential effects on localization, RB phosphorylation, and cellular transformation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30339–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Agami R, Bernards R. Distinct initiation and maintenance mechanisms cooperate to induce G1 cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2000;102:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cariou S, Donovan JC, Flanagan WM, Milic A, Bhattacharya N, Slingerland JM. Down-regulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 or p27Kip1 abrogates antiestrogen-mediated cell cycle arrest in human breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9042–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160016897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Thome M, Tschopp J. Regulation of lymphocyte proliferation and death by FLIP. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:50–8. doi: 10.1038/35095508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Budd RC, Yeh WC, Tschopp J. cFLIP regulation of lymphocyte activation and development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:196–204. doi: 10.1038/nri1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Krueger A, Baumann S, Krammer PH, Kirchhoff S. FLICE-inhibitory proteins: regulators of death receptor-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8247–54. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8247-8254.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Krueger A, Schmitz I, Baumann S, Krammer PH, Kirchhoff S. Cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein splice variants inhibit different steps of caspase-8 activation at the CD95 death-inducing signaling complex. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20633–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sharp DA, Lawrence DA, Ashkenazi A. Selective knockdown of the long variant of cellular FLICE inhibitory protein augments death receptor-mediated caspase-8 activation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19401–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]