Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Traumatic life histories are highly prevalent in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and predict sexual risk behaviors, medication adherence, and all-cause mortality. Yet the causal pathways explaining these relationships remain poorly understood. We sought to quantify the association of trauma with negative behavioral and health outcomes and to assess whether those associations were explained by mediation through psychosocial characteristics.

METHODS

In 611 outpatient PLWHA, we tested whether trauma's influence on later health and behaviors was mediated by coping styles, self efficacy, social support, trust in the medical system, recent stressful life events, mental health, and substance abuse.

RESULTS

In models adjusting only for sociodemographic and transmission category confounders (estimating total effects), past trauma exposure was associated with 7 behavioral and health outcomes including increased odds or hazard of recent unprotected sex (OR=1.17 per each additional type of trauma, 95% CI=1.07–1.29), medication nonadherence (OR=1.13, 1.02–1.25), hospitalizations (HR=1.12, 1.04–1.22), and HIV disease progression (HR=1.10, 0.98–1.23). When all hypothesized mediators were included, the associations of trauma with health care utilization outcomes were reduced by about 50%, suggesting partial mediation (e.g., OR for hospitalization changed from 1.12 to 1.07) whereas point estimates for behavioral and incident health outcomes remained largely unchanged, suggesting no mediation (e.g., OR for unprotected sex changed from 1.17 to 1.18). Trauma remained associated with most outcomes even after adjusting for all hypothesized psychosocial mediators.

CONCLUSIONS

These data suggest that past trauma influences adult health and behaviors through pathways other than the psychosocial mediators considered in this model.

Keywords: Trauma, Mental health, Adherence, Health outcomes, Mediation analysis

Traumatic life experiences such as childhood sexual and physical abuse are recognized as having profound and far-reaching implications for health and health-related behaviors.1 Early research on childhood trauma documented elevated rates of a range of psychological disorders in survivors of childhood sexual and physical abuse. Later studies have extended these findings, first by considering a wider range of lifetime traumatic experiences,1 and second by demonstrating associations of traumatic exposure with harmful health behaviors (high-risk sexual behaviors, poor adherence to medical treatments) as well as increased somatization, poorer health outcomes, and higher mortality rates.2–4 These associations are particularly pronounced and consistent in medically ill populations, including people living with HIV/AIDS.5–7

Although this literature suggests far-reaching health consequences of childhood traumatic experiences, a theoretical understanding of the causal pathways through which past trauma influences later health behaviors and outcomes is incomplete. Proposed causal mediators include both psychosocial and physiologic responses to trauma.6 Briere and colleagues suggest that childhood sexual and physical abuse can impact psychological symptoms into adulthood.2, 3, 8 Other research postulates that traumatization, especially early in life, can have a direct effect on physiologic processes including suppressing immune function.6 However, empirical tests of the causal models relating trauma to health outcomes are rare.

The purpose of the present paper is twofold. First, drawing on data from a large cohort of patients receiving outpatient care for HIV infection with detailed information on traumatic exposure, psychosocial characteristics, health care utilization, health behaviors, and health outcomes, we document elevated rates of a range of deleterious outcomes associated with lifetime trauma exposure. Second, we empirically test the extent to which these observed associations between trauma and later outcomes can be explained by mediation through psychosocial pathways in order to extend our understanding of the causal mechanisms underlying these relationships.

METHODS

Study design and sample

This paper draws on data from the Coping with HIV/AIDS in the Southeast (CHASE) Study, an observational cohort study designed to describe and explore the associations between psychological characteristics, health behaviors, and health outcomes in HIV-infected patients engaged in medical care. The CHASE Study sampling and recruitment procedures have been described in detail previously.9, 10 In brief, 611 consecutively sampled HIV-infected patients (79% of those meeting eligibility criteria and approached) receiving care at one of eight infectious diseases clinics in five U.S. states (AL, GA, LA, NC, SC) in 2001–2002 enrolled in the study. Patients completed detailed interviews at baseline and approximately 9, 18, and 27 months post-baseline. The resulting sample closely matched the epidemiologic profile of HIV-infected individuals in the source states in demographic and risk group characteristics.9

Each of a previous set of publications from the CHASE Study focused on a different behavioral or health outcome or set of outcomes (adherence; health care utilization; disease progression; mortality). In each case, trauma emerged as an important predictor even after controlling for various sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial covariates.10–13 The purpose of the present paper is to apply a uniform analytic approach across a range of outcomes in order to specifically test the explanatory power of psychosocial characteristics as mediators of the association of trauma with health behaviors and outcomes.

Mediation Analysis

The analysis plan follows a classic multiple-step mediation analysis approach, represented in simplified form in Figure 1.14–17 Mediation analysis has been widely applied in psychosocial research and is gaining increasing attention in biomedical applications.18, 19 Mediation analysis focuses on separating an observed association – a total effect – into an indirect effect (the portion that operates through one or more specified mediators, or causal pathways) and a direct effect (the portion that does not operate through those mediators). The analysis approach evaluates the hypothesis that a given set of mediators explains the causal pathways through which an exposure affects an outcome, or conversely the extent to which an exposure has a persistent association with an outcome independent of the casual pathways represented by the mediators. In contrast to a confounder, a mediator is explicitly on the causal pathway between exposure and outcome – part of the mechanism that transmits the exposure's effect on the outcome

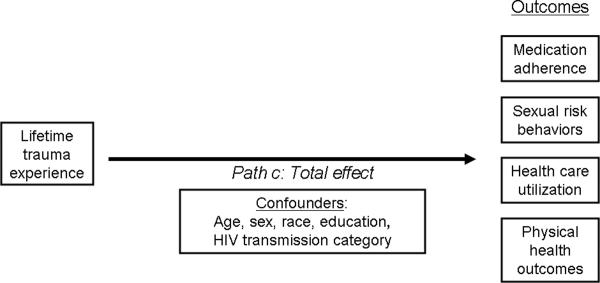

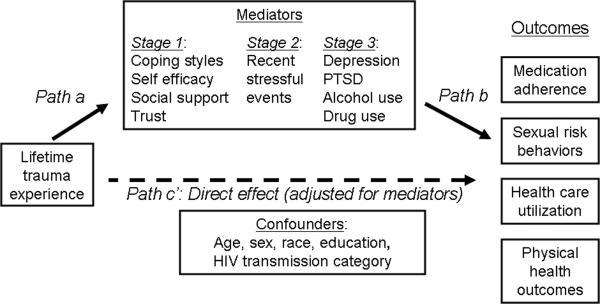

Figure 1.

Mediation analysis.

Figure 1(a). Model estimating the total effect (path c) of lifetime trauma experience on health behaviors and outcomes, adjusted for confounders.

Figure 1(b). Model estimating the remaining direct effect (path c') of lifetime trauma experience on health behaviors and outcomes, after adjusting for hypothesized mediators. If the mediators explain all of the causal pathways through which trauma affects outcomes, we would expect path c' to be null. If the mediators explain none of the effect of trauma on outcomes, we would expect path c' to approximately equal path c from Figure 1a. If the mediators explain part of the pathways through which trauma affects outcomes, we would expect path c' to be attenuated relative to path c but non-null.

Mediation analysis begins with the specification of the hypothesized causal relations among the variables being considered (Figure 1). By definition, a mediator must be caused by the exposure (path a), and in turn must affect the outcome (path b). The core of the analysis focuses on a comparison of path c (Figure 1a) to path c' (Figure 1b). Path c is estimated from a model including only potential confounders (covariates not on the causal pathway), and represents the total effect of the exposure on the outcome. Path c' is estimated from a model adjusting both for confounders and hypothesized mediators, and represents the direct effect of the exposure on the outcome: that portion of the total effect that does not operate through the mediators. If the total effect and the direct effect are comparable in magnitude, one concludes that the hypothesized mediators do not mediate the exposure-outcome relationship. If the total effect indicates an association but the direct effect is null, one concludes that the mediators completely explain the association: the exposure only affects the outcome by way of the mediators included in the model. If the direct effect is attenuated relative to the total effect but still indicates some association, one concludes that the mediators represent part but not all of the causal pathways through which the exposure affects the outcome.14–19

Model specification

Our focus in the present analysis was, first, to estimate the association of lifetime trauma history with each of a set of HIV-related behavioral and health outcomes – path c, total effects – and second, to estimate the association that remained after adjusting for a set of hypothesized mediators – path c', direct effects (Figure 1). We hypothesized that the effect of lifetime trauma history on behaviors and health outcomes would be mediated through current psychosocial characteristics including coping styles, self-efficacy, social support, trust in the health care system, recent stressful life events, and current depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and substance use. We first developed a causal diagram to depict the hypothesized temporal ordering and causal relationships between all the variables under consideration. We

conceptualized the mediators as occurring in three stages (trait-like characteristics, recent events, current mental health). Figure 1 is a simplified version of this diagram for ease of communicating the primary message. Our causal diagram indicated that adjustment for all variables in the Confounders box in Figure 1 would be sufficient to estimate the total effect c, and further adjustment for all variables in the Mediators box in Figure 1 would be sufficient to estimate the direct effect c' that was not mediated through those variables.

Measures

Number of categories of lifetime traumatic events

The psychosocial trauma measure, adapted from prior research, included sexual abuse, severe physical trauma, childhood physical and emotional neglect, and other traumatic experiences.20–23 We defined sexual abuse to include sexual experiences (e.g., touching, intercourse) where force or threat of force was used; however, in children (<13 years) the threat of force or harm was implied by a 5-year age differential between the victim and perpetrator. We defined physical abuse as incidents separate from sexual abuse that were perceived to be life threatening (being physically attacked with the intent to kill or seriously injure), and other physical abuse (being beaten, hit, kicked, bit, or burned). Childhood physical and emotional neglect were measured with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire and scored using the cutoffs suggested by Bernstein and Fink for moderate physical neglect (≥9) and moderate emotional neglect (≥12).20 Other traumas before age 18 were parental alcohol/drug abuse, depression, suicide or attempted suicide; imprisonment of a parent; domestic violence in the home; being placed in reform school, prison or jail, or foster or adoptive care; death of an immediate family member; and having a life-threatening illness or injury not related to HIV. Lifetime traumas included murder of a close family member, death of a child, death of a spouse/partner, and other similar traumas specified by the subject and later assessed by one of the authors (JL) to be similar in severity to those listed above. Participants were assigned a score from 0 to 15 reflecting the number of types of traumatic events experienced in their lifetime. This specification of the number of types of traumatic events experienced has been used widely and has been associated with multiple negative health outcomes.4, 10, 12, 24, 25

Outcome variables

Focusing on health-related behaviors and physical health outcomes, we examined four domains of outcome variables: reported sexual risk behaviors, antiretroviral medication adherence, health care utilization, and physical health. Sexual risk behavior over the past 9 months was dichotomized as any self-reported sexual intercourse without a condom (dichotomous). The medication adherence measure was derived from the Patient Care Committee and the Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trial Group26 and has been described in detail previously.12 Patients were considered non-adherent if they reported missing any ARV doses during the past 7 days. In this sample, self-reported adherence was strongly correlated with an undetectable viral load at baseline (OR=2.09, p = 0.002).

Health care utilization outcomes, assessed over the past 9 months by participant self-report, included any overnight hospitalization and any emergency department (ED) visit not including hospitalization. Health outcomes included the SF-36 physical composite score (range: 0–100) measured via self-report; number of days where more than half the day was spent in bed, dichotomized as low (0–4) versus high (≥5) (based on prior studies27); as well as HIV disease progression, defined as time from enrollment to either an incident Category C opportunistic infection (OI) or AIDS-related mortality during longitudinal follow-up. OIs and mortality were assessed via retrospective, standardized chart review at all sites. Death was considered AIDS-related if the cause of death was an OI (N=12) or if the cause of death was unknown but the most recent CD4 count prior to death was <200 cells/mm3 or a Category C OI was noted in the 12 months prior to death (N=4).

Putative mediating variables

Coping styles were evaluated with 16 items from the Brief Cope.28 Consistent with previous definitions,12, 28, 29 we formed two scales of adaptive (positive reframing, using emotional support, acceptance, religion, active) and maladaptive (denial, self blame, and behavioral disengagement) coping styles, which were uncorrelated (ρ = −0.07) and had satisfactory internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha = 0.74 and 0.72, respectively) in this sample.

Social support was assessed with the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey,30 and the Pearlin Self-Efficacy Scale was used to measure self-efficacy.31 Both measures have high internal and construct validity. As previously described,32trust was represented by two scales created from Likert-scale questions: trust in the participant's HIV doctor and trust in the government. PTSD symptomatology for the 9 months before baseline was measured with the PTSD checklist33, 34 based on DSM-IV criteria that include re-experiencing a traumatic event, numbing/avoiding, and hyperarousal symptoms. This scale has strong reported reliability, and correlates highly with a clinician-administered PTSD measure. Depressive symptoms were measured using the 6-item depression subscale of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI),35 a shortened version of the well-validated Symptoms Checklist-90. Alcohol and drug use were measured by the widely used Addiction Severity Index (ASI), with alcohol and drug ASI composite scores calculated according to standard procedures.36

Statistical analysis

We modeled dichotomous outcomes (any unprotected sex; any medication nonadherence; hospitalization; ED use; >4 days in bed) using logistic regression models, normally distributed outcomes (SF36 physical health score) using linear regression models, and time-to-event outcomes (time to HIV disease progression) using Cox proportional hazards regression models.

For each outcome, we fit the following series of models. Model.1 included only lifetime trauma history as a predictor and thus estimated the crude association of trauma with the outcome. In Model 2 we added potential confounders: age, race, sex, educational attainment, and self-reported HIV transmission category (male-to-male sex, heterosexual sex, injection drug use, other, unknown) to estimate the total effect (path c), adjusted for confounding. In Model 3 we added Stage 1 mediators (cf. Figure 1); in model 4 we added Stage 2 mediators; and in Model 5 we added Stage 3 mediators. For the HIV disease progression outcome, we added Model 6 which included baseline CD4 count and duration of antiretroviral treatment as additional mediators. Thus the coefficients for lifetime trauma history in Model 5 (or Model 6 for disease progression) correspond to path c': the remaining direct effect after accounting for the hypothesized mediating pathways.

We calculated the mediation ratio as (c-c)'/c, representing the proportion of the estimated total effect that is attributable to the mediators in the model. For logistic and Cox proportional hazards models, this ratio was calculated using the unexponentiated coefficients (log odds ratios and log hazard ratios). Following Shrout,37 we used bootstrapping to obtain confidence intervals around the mediation ratio, reporting the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the mediation ratios from 1,000 replications as the 95% confidence interval. Also following Shrout, we report estimated mediation ratios and 95% CI bounds of <0% and >100% as 0% and 100% respectively.

RESULTS

Sample description

Participants in the CHASE Study were primarily between 30 and 50 years of age; approximately one-third were female and 44% were men who reported having sex with other men (Table 1). Approximately two-thirds were of African American race and one-third were Caucasian non-Hispanic. Participants had been infected with HIV for a mean of 6.8 years (standard deviation: 4.4 years). Three-quarters were on antiretroviral therapy and 46% had an HIV RNA viral load <400 copies/mL at baseline.

Table 1.

Description of the CHASE sample (n=611)

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years (range 20–71) | 40.1 (8.7) |

| Female gender | 191 (31.3%) |

| Man who has had sex with other men | 268 (43.9%) |

| Race/ethnicity: | |

| Caucasian non-Hispanic | 189 (31.6%) |

| African American non-Hispanic | 383 (64.1%) |

| Hispanic | 16 (2.7%) |

| Other | 10 (1.7%) |

| Self-reported HIV transmission category | |

| Male-to-male sex | 220 (36.0%) |

| Heterosexual sex | 261 (42.7%) |

| Injection drug use | 40 (6.6%) |

| Other | 25 (4.1%) |

| Unknown | 65 (10.6%) |

| Education, years (range: 3–18) | 12.4 (2.0) |

| Years since HIV diagnosis (range: 0–21) | 6.8 (4.4) |

| On antiretroviral therapy | 474 (77.6%) |

| CD4 count, cells/mm3 (range: 0–1,580) | 415 (285) |

| HIV RNA viral load <400 copies/mL | 237 (46.1%) |

| Mental health and substance use indicators | |

| Probable post-traumatic stress disorder | 98 (16.0%) |

| Depressive symptoms >90th percentile | 212 (34.7%) |

| Drank to intoxication weekly, past 9 months | 40 (6.9%) |

| Any non-marijuana drug use, past 9 months | 136 (22.3%) |

Distribution of exposure and outcomes

Participants reported a median of 3 types of lifetime traumatic experiences (range: 0–12; IQR: 1–4) (Table 2). Twelve percent reported having had unprotected sex in the past 9 months and 24% of those on ARVs reported having missed a dose in the past week. Twenty-six percent had been hospitalized and 39% had visited the ED. Participants' overall physical health was slightly worse than the US population average (median SF36 score = 48; US population mean = 50), and 33% had spent >4 days in bed in the past 9 months. HIV disease progression (incident OI or AIDS-related death) was observed in 50 participants over a total of 1,033 person-years of observation.

Table 2.

Distribution of exposure, outcome, and hypothesized mediating variables.

| Variable | Median (IQR), n (%), or n (pyo) |

|---|---|

| Primary exposure | |

| Number of types of lifetime traumatic experiences (range: 0–12) | 3 (1–4) |

| Outcomes | |

| Any unprotected sex, past 9 months | 69 (12.3%) |

| Antiretroviral nonadherence, past week | 112 (23.6%) |

| Any hospitalization, past 9 months | 160 (26.3%) |

| Any emergency department visit, past 9 months | 239 (39.2%) |

| SF36 physical health (range: 0–100) | 48 (38–54) |

| >4 days in bed >half the day, past 9 months | 196 (33.4%) |

| HIV disease progression over 27 months of follow-up | 50 (1033 pyo) |

| Hypothesized mediating variables | |

| Adaptive coping styles (range: 1–4) | 3.1 (2.7–3.5) |

| Maladaptive coping styles (range: 1–4) | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) |

| Social support (range: 1–5) | 4.1 (3.2–4.7 |

| Self efficacy (range: 1–4) | 3.1 (2.7–3.6) |

| Trust in doctor (range: 1–5) | 4.7 (4.3–5) |

| Trust in government (range: 1–5) | 3.5 (2.5–4) |

| Stressful events, past 9 months | 3 (2–5) |

| PTSD symptomatology (range: 17–85) | 27 (21–37) |

| Depressive symptomatology (range: 0–100) | 55 (44–65) |

| Alcohol use (ASI) (range: 0–100) | 0 (0–2) |

| Drug use (ASI) (range: 0–100) | 0 (0–0) |

IQR: Interquartile range. PYO: Person-years of observation. ASI: Addiction severity index. PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Unadjusted associations

In bivariable models (Model 1), greater lifetime trauma exposure was associated with all outcomes considered (Table 3). Each additional type of lifetime trauma was associated with 18% (95% CI: 9–28%) increased odds of unprotected sex, 13% (3–24%) increased odds of ARV nonadherence, 12% (4–21%) increased odds of hospitalization, 14% (6–22%) increased odds of ED use, 13% (5–22%) increased odds of more than 4 days in bed, a 12% (0–24%) increased hazard of HIV disease progression, and a 0.8-unit (0.4–1.2) lower SF36 physical health score. These estimates shifted only marginally after adjustment for the potential confounders of age, race, sex, education, and self-reported HIV transmission category (Model 2).

Table 3.

Association of trauma with behavioral and health outcomes, and assessment of mediation by psychosocial variables.

| Outcome (reported estimate) | Unadjusted association | Association adjusted for confounders (path c) | Association adjusted for confounders and all Stage 1-Stage 3 mediators (path c′) | Mediation ratio (c-c′)/c and bootstrapped 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association of trauma with … | ||||

| Any unprotected sex (OR) | 1.18 (1.09, 1.28) | 1.17 (1.07, 1.29) | 1.18 (1.06, 1.32) | 0%† (0–66%) |

| ARV nonadherence (OR) | 1.13 (1.03, 1.24) | 1.13 (1.02, 1.25) | 1.15 (1.02, 1.29) | 0%† (0–52%) |

| Any hospitalization (OR) | 1.12 (1.04, 1.21) | 1.12 (1.04, 1.22) | 1.07 (0.97, 1.18) | 39% (0–100%) |

| Any emergency department visit (OR) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | 1.12 (1.04, 1.21) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.17) | 41% (0–100%) |

| >4 days in bed >half the day (OR) | 1.13 (1.05, 1.22) | 1.13 (1.04, 1.22) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.17) | 50% (0–100%) |

| HIV disease progression (HR) | 1.12 (1.00, 1.24) | 1.10 (0.98, 1.23) | 1.12 (0.97, 1.30) | 0%† (0–100%) |

| SF36 physical health score (β) | −0.8 (−1.2, −0.4) | −0.8 (−1.2, −0.4) | −0.7 (−1.1, −0.3) | 12% (0–67%) |

ARV: Antiretroviral. OR: Odds ratio. HR: Hazard ratio. β: Ordinary least squares regression coefficient. CI: Confidence interval.

Mediation ratio estimates and confidence interval limits <0% and >100% are reported as 0% and 100% respectively.

Mediation analysis

In comparing the model adjusted only for confounders (Model 2, path c) to the model additionally adjusting for all potential mediators (Model 5 or Model 6, path c'), the odds ratio for each additional type of lifetime trauma shifted from 1.17 to 1.18 (95% CI: 1.06–1.32) for unprotected sex, from 1.13 to 1.15 (1.02–1.29) for medication nonadherence, from 1.12 to 1.07 (0.97–1.18) for hospitalization, from 1.12 to 1.07 (0.98–1.17) for ED use, and from 1.13 to 1.06 (0.97, 1.17) for >4 days in bed (Table 3). The hazard ratio for HIV disease progression shifted from 1.10 to 1.12 (0.97, 1.30). In modeling the SF36 physical health score, the coefficient for trauma shifted from −0.8 to −0.7 (−1.1 to −0.3).

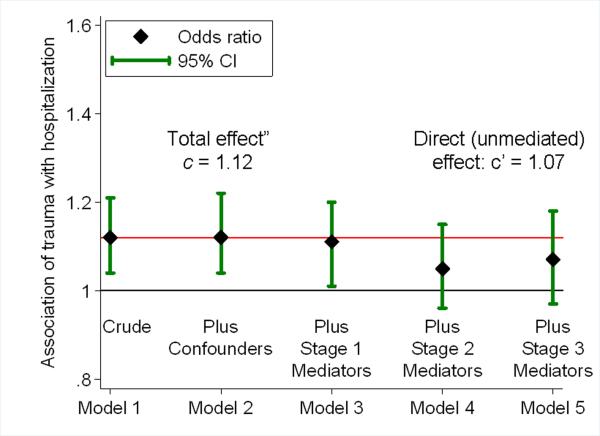

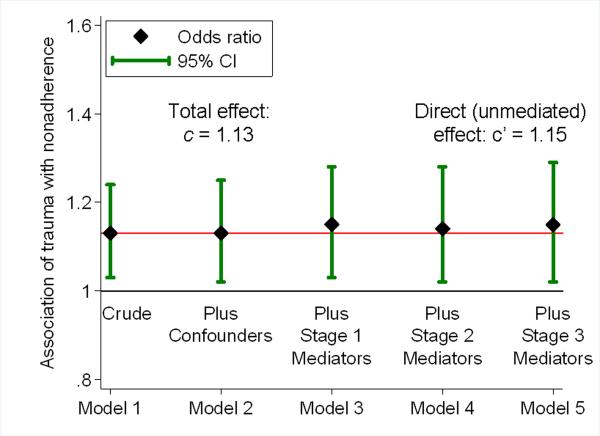

The mediation ratio for the combined effects of all putative mediators was 39% for hospitalizations, 41% for ED use, 50% for >4 days in bed, 12% for SF36 physical health scores, and <0% for unprotected sex, medication nonadherence, and HIV disease progression. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals around the mediation ratios were wide. Although point estimates for unprotected sex, medication nonadherence, and HIV disease progression shifted unexpectedly away from the null upon adjustment for mediators, these shifts were minor relative to the sampling uncertainty (confidence intervals) around the estimates. For bed days, hospitalization, and ED use, the largest shift in point estimates was between Models 3 and 4, with the addition to the model of the Stage 2 mediator (recent stressful life events) (Figure 2a). Point estimates for other outcomes changed little between Models 2 and 5 (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Association of lifetime trauma exposure with (a) odds of any hospitalization in past 9 months and (b) odds of antiretroviral nonadherence in past week, and assessment of mediation by psychosocial characteristics. Path c represents the total effect adjusted for confounders; path c' represents the remaining direct effect after accounting for mediation by psychosocial characteristics.

DISCUSSION

Two primary observations emerge from these analyses. First, in models designed to estimate the total effect of trauma on HIV outcomes (i.e., adjusting for sociodemographic confounders but excluding potential mediators), greater lifetime exposure to traumatic experiences is associated with a wide range of deleterious behavioral and health consequences in this sample of people living with HIV. It should be noted that we reported associations in terms of each one-unit increase in the continuously measured trauma exposure variable. If one additional type of trauma is associated with a 13% increased odds of nonadherence, for example, an individual with the sample median of 3 lifetime traumatic experiences would be expected to have 44% increased odds of medication nonadherence (1.133 = 1.44) compared to someone with no trauma history. This finding is consistent with research that suggests a cumulative effect of lifetime traumatic experiences on health-related outcomes.1 It also supports findings that trauma may accelerate disease progression in individuals living with HIV.38, 39

Second, trauma history demonstrated persistent associations with this wide range of behavioral and health outcomes even after adjustment for a detailed set of hypothesized psychosocial mediators. While about half of the association of trauma with health care utilization outcomes appeared mediated by psychosocial variables (in particular, recent stressful events), there was no evidence of psychosocial mediation for the associations between trauma and behavioral (sexual risk behaviors and medication adherence) or health outcomes (physical symptoms and HIV disease progression).

The observation that none of the proposed psychosocial mediators fully explains the association between lifetime trauma and HIV-related outcome variables suggests the consideration of other causal pathways. Behavioral and lifestyle-related factors not measured in this study that may help explain the effect of early trauma on later health and behaviors include effects of trauma on low self-esteem, dissociative symptoms, worse self-care behaviors such as nutrition and exercise, and predisposition to experiencing other traumatic situations such as intimate partner violence.40–42 Some recent research also suggests that biological or neurological pathways may explain part of the effect of trauma on later health, for example through dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal [HPA] axis (e.g., higher cortisol) and greater autonomic activation (e.g., higher catecholamines).43–49 Recent neuroimaging studies have also begun to document lasting changes in areas of the brain, specifically the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, associated with traumatic stress.50

While this dataset was rich in psychosocial measures, it did not include markers of potential physiologic pathways such as cortisol38 and natural killer cells51, 52 that would have allowed a direct comparison of the explanatory power of psychosocial versus physiologic mediators. However, our study does make a significant contribution to the growing body of research which suggests that the cumulative burden of lifetime trauma affects a variety of outcomes for individuals living with HIV.6 By failing to fully explain our results based on a range of psychosocial mediators, it highlights the importance of further research to better understand the mechanisms through which trauma affects later health and health-related behaviors.

Strengths of this study include the large, multi-site sample, the consecutive sampling strategy, the longitudinal design, the detailed lifetime trauma history, and the wide range of psychosocial domains systematically assessed with validated measures. While the sample is reflective of HIV patients in care in the southern United States, the results may not generalize to more urbanized parts of the country or to HIV-infected individuals not in medical care.

Psychosocial characteristics vary over time. The putative mediators may have had different values at the time they were measured for this study than at the time they would have exerted their mediating influence, or may have been imprecisely measured by the scales selected. This measurement bias would tend to attenuate the associations of the mediators with the exposure and outcome variables, potentially underestimating the importance of the mediators' role. All mediators were measured at both baseline and 27 months, and the intraclass correlation coefficients for this set of variables between the two time points ranged between 0.41 and 0.59, suggesting moderate stability of the mediators over an extended time period. Measurement error may also have affected our self-reported measure of trauma history, most likely through omission of past events, although the severity of the experiences queried on the trauma assessment would tend to reduce such under-reporting.

Confidence intervals around the mediation ratios were broad, reflecting the general low power of tests of mediation even in large samples such as this one. However, it is notable that even these broad confidence intervals excluded complete mediation (mediation ratio of 100%) for medication adherence, unprotected sexual intercourse, and general health, suggesting that even if these psychosocial pathways explain part of the association of trauma with outcomes, at least part of the effect likely goes through other pathways.

In summary, the present study supports other research in documenting strong associations of past trauma with a wide range of negative health-related behaviors and health outcomes in HIV-infected patients. It additionally suggests that these associations are largely not mediated by a range of psychosocial characteristics including coping, self efficacy, social support, trust, stressful events, and current mental health and substance abuse. Further research on the mechanisms through which trauma impacts later behaviors and health is essential in order to build effective interventions that will promote use of safer sexual practices, optimal antiretroviral medication adherence, and better health outcomes for HIV-infected patients.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This study was supported by grant 1 R03 MH081776-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The original CHASE study was supported by the NIMH, the National Institute of Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Nursing Research (Grant# 5R01MH061687-05) of the NIH. MJM is supported by grant K23MH082641 from the NIMH of the NIH. NMT is supported by grant U01 AI069484 from NIAID of the NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH or the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosures of conflicts of interest: All authors have no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Previous presentations: 2010 American Psychosomatic Society Annual Meeting, Portland, OR, March 10–12, 2010; 6th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence, Miami, FL, May 22–24, 2011.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sledjeski EM, Speisman B, Dierker LC. Does number of lifetime traumas explain the relationship between PTSD and chronic medical conditions? Answers from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) J Behav Med. 2008;31:341–349. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briere J, Elliott DM. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1205–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briere JN, Elliott DM. Immediate and long-term impacts of child sexual abuse. Future Child. 1994;4:54–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyatt GE, Myers HF, Loeb TB. Women, Trauma, and HIV: an overview. AIDS Behav. 2004;8:401–403. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brief DJ, Bollinger AR, Vielhauer MJ, et al. Understanding the interface of HIV, trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use and its implications for health outcomes. AIDS Care. 2004;16(Suppl 1):S97–120. doi: 10.1080/09540120412301315259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:539–545. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181777a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briere J, Runtz M. Symptomatology associated with childhood sexual victimization in a nonclinical adult sample. Child Abuse Negl. 1988;12:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(88)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pence BW, Reif S, Whetten K, et al. Minorities, the poor, and survivors of abuse: HIV-infected patients in the US deep South. South Med J. 2007;100:1114–1122. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000286756.54607.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leserman J, Whetten K, Lowe K, Stangl D, Swartz MS, Thielman NM. How trauma, recent stressful events, and PTSD affect functional health status and health utilization in HIV-infected patients in the south. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:500–507. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000160459.78182.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leserman J, Pence BW, Whetten K, et al. Relation of lifetime trauma and depressive symptoms to mortality in HIV. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1707–1713. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mugavero M, Ostermann J, Whetten K, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral adherence: the importance of depression, abuse, and other traumatic events. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:418–428. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mugavero MJ, Pence BW, Whetten K, et al. Predictors of AIDS-Related Morbidity and Mortality in a Southern U.S. Cohort. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:681–690. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacKinnon DP. Analysis of mediating variables in prevention and intervention research. NIDA Res Monogr. 1994;139:127–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacKinnon DP. Contrasts in multiple mediator models. In: Rose JS, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, editors. Multivariate Applications in Substance Use Research: New Methods for New Questions. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryan A, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. Mediational analysis in HIV/AIDS research: estimating multivariate path analytic models in a structural equation modeling framework. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:365–383. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Allison JJ, et al. Racial disparities in HIV virologic failure: do missed visits matter? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:100–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5c37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernstein D, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Manual. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kilpatrick D, Resnick HS. A description of the posttraumatic stress disorder field trial. In: Davidson J, Foa EB, editors. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. American Psychiatric Press; Washington DC: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koss MP, Gidycz CA. Sexual experiences survey: reliability and validity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:422–423. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leserman J, Li Z, Drossman DA, Toomey TC, Nachman G, Glogau L. Impact of sexual and physical abuse dimensions on health status: development of an abuse severity measure. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:152–160. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199703000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liebschutz JM, Feinman G, Sullivan L, Stein M, Samet J. Physical and sexual abuse in women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: increased illness and health care utilization. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1659–1664. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leserman J, Drossman DA, Li Z, Toomey TC, Nachman G, Glogau L. Sexual and physical abuse history in gastroenterology practice: how types of abuse impact health status. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:4–15. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carver C. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pence BW, Thielman NM, Whetten K, Ostermann J, Kumar V, Mugavero MJ. Coping strategies and patterns of alcohol and drug use among HIV-infected patients in the U.S. Southeast. AIDS Care. 2008 doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0022. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, Mullan JT. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whetten K, Leserman J, Whetten R, et al. Exploring lack of trust in care providers and the government as a barrier to health service use. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:716–721. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weathers F, Ford J. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist. In: Stamm B, editor. Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation. Sidran Press; Lutherville, MD: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leserman J, Petitto JM, Golden RN, et al. Impact of stressful life events, depression, social support, coping, and cortisol on progression to AIDS. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1221–1228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reilly KH, Clark RA, Schmidt N, Benight CC, Kissinger P. The effect of post-traumatic stress disorder on HIV disease progression following hurricane Katrina. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1298–1305. doi: 10.1080/09540120902732027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Becker DF, Grilo CM. Childhood maltreatment in women with binge-eating disorder: Associations with psychiatric comorbidity, psychological functioning, and eating pathology. Eat Weight Disord. 16:e113–120. doi: 10.1007/BF03325316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNutt LA, Carlson BE, Persaud M, Postmus J. Cumulative abuse experiences, physical health and health behaviors. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutherland MA. Examining mediators of child sexual abuse and sexually transmitted infections. Nurs Res. 60:139–147. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318209795e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss SJ. Neurobiological alterations associated with traumatic stress. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2007;43:114–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2007.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanitallie TB. Stress: a risk factor for serious illness. Metabolism. 2002;51:40–45. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.33191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heim C, Ehlert U, Hanker JP, Hellhammer DH. Abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder and alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in women with chronic pelvic pain. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:309–318. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lemieux AM, Coe CL. Abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence for chronic neuroendocrine activation in women. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:105–115. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Bellis MD, Lefter L, Trickett PK, Putnam FW., Jr. Urinary catecholamine excretion in sexually abused girls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:320–327. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199403000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elzinga BM, Schmahl CG, Vermetten E, van Dyck R, Bremner JD. Higher cortisol levels following exposure to traumatic reminders in abuse-related PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1656–1665. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bremner JD. Neuroimaging in posttraumatic stress disorder and other stress-related disorders. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2007;17:523–538. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greeson JM, Hurwitz BE, Llabre MM, Schneiderman N, Penedo FJ, Klimas NG. Psychological distress, killer lymphocytes and disease severity in HIV/AIDS. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:901–911. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans DL, Lynch KG, Benton T, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and substance P antagonist enhancement of natural killer cell innate immunity in human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:899–905. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]