Abstract

Colitis-associated colorectal cancers are an etiologically distinct subgroup of colon cancers that occur in individuals suffering from inflammatory bowel disease and arise as a consequence of persistent exposure of hyperproliferative epithelial stem cells to an inflammatory microenvironment. An intrinsic defect in the intestinal epithelial barrier has been proposed to be one of several factors that contribute to the inappropriate immune response to the commensal microbiota that underlies inflammatory bowel disease. Matriptase is a membrane-anchored serine protease encoded by Suppression of Tumorigenicity-14 (ST14) that strengthens the intestinal epithelial barrier by promoting tight junction formation. Here we show that intestinal epithelial-specific ablation of St14 in mice causes formation of colon adenocarcinoma with very early onset and high penetrance. Neoplastic progression is preceded by a chronic inflammation of the colon that resembles human inflammatory bowel disease and is promoted by the commensal microbiota. This study demonstrates that inflammation-associated colon carcinogenesis can be initiated and promoted solely by an intrinsic intestinal permeability barrier perturbation, establishes St14 as a critical tumor suppressor gene in the mouse gastrointestinal tract, and adds matriptase to the expanding list of pericellular proteases with tumor suppressive functions.

Introduction

Colitis-associated colorectal cancers are etiologically and molecularly distinct from familial adenomatous polyposis coli-associated colorectal cancer, hereditary non-polyposis coli colorectal cancer, and sporadic colorectal cancer. The malignancy occurs in individuals suffering from ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease (collectively, inflammatory bowel disease) with an incidence that is proportional to duration of the disease. The neoplastic progression of disease-striken colonic epithelium is believed to be driven by the chronic inflammatory microenvironment, which promotes the progressive genomic instability of colonic epithelial stem cells by inducing sustained hyperproliferation (regenerative atypia) and by the continuous presence of high local concentrations of DNA damaging agents, such as reactive oxygen species (reviewed in (Danese and Mantovani, 2010, Saleh and Trinchieri, 2011)).

While there is considerable debate about the relative importance of the specific factors that contribute to the development of inflammatory bowel disease, there is a consensus that the disease represents an inappropriate immune response to the commensal microbiota in genetically predisposed individuals (reviewed in (Kaser et al., 2010, Saleh and Trinchieri, 2011, Schreiber et al., 2005, Van Limbergen et al., 2009, Xavier and Podolsky, 2007)). In this regard, the contribution of aberrant inflammatory circuits to the development of inflammatory bowel disease has been clearly established by genetic analysis, including genome-wide association studies, that have linked loss of function mutations or polymorphisms in genes encoding interleukins, interleukin receptors, chemokine receptors, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors, toll-like receptor 4, intelectins, and prostaglandin receptors to ulcerative colitis, to Crohn’s disease or to both. Further support for a principal role of derailed inflammatory circuits is gained from the spontaneous inflammatory bowel disease observed in mice deficient in a variety of immune effectors (reviewed in (Kaser et al., 2010, Saleh and Trinchieri, 2011, Schreiber et al., 2005, Van Limbergen et al., 2009, Xavier and Podolsky, 2007)). Much less explored is the importance of individual components of the intestinal epithelial barrier in preventing inflammatory bowel disease, and the potential contribution of intrinsic intestinal epithelial barrier defects to the development of the syndrome. The clearest indication of the potential importance of primary barrier integrity comes from studies of mice with germline ablation of Muc2 encoding the major mucin that shields the intestinal epithelium from direct contact with the microbiota. These mice develop colitis, which may progress to colon adenocarcinomas in older animals (Velcich et al., 2002). Additional evidence has been obtained from transgenic mice with intestinal epithelial-specific overexpression of myosin light chain kinase, which display decreased barrier function and increased immune activation, although an inflammatory bowel-like syndrome did not emerge in the absence of additional immunological challenges (Su et al., 2009).

Matriptase is a member of the recently established family of type II transmembrane serine proteases that is encoded by the Suppression of Tumorigenicity-14 (ST14) gene (Bugge et al., 2009, Kim et al., 1999, Lin et al., 1999, Takeuchi et al., 1999, Tanimoto et al., 2001). ST14 was originally proposed to be a colon cancer tumor suppressor gene, due to its specific down-regulation in adenocarcinomas of the colon (Zhang et al., 1998). Matriptase is expressed in multiple epithelia of the integumental, gastrointestinal, and urogenital systems, where it has pleiotropic functions in the differentiation or homeostasis of both simple and stratified epithelia, at least in part through the proteolytic activation of the epithelial sodium channel activator, prostasin/PRSS8 (Szabo and Bugge, 2011). In simple epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract, a principal function of matriptase is to promote the formation of a paracellular permeability barrier, possibly through the posttranslational regulation of the composition of claudins that are incorporated into the epithelial tight junction complex of differentiating intestinal epithelial cells (Buzza et al., 2010, List et al., 2009).

Through lineage-specific loss of function analysis in mice we now have examined the role of St14 as a tumor suppressor gene. Interestingly, we found that the selective ablation of St14 from intestinal epithelium results in the formation of adenocarcinoma of the colon with very early onset and high penetrance. Neoplastic progression occurs in the absence of exposure of animals to carcinogens or tumor promoting agents, is preceded by chronic colonic inflammation that resembles human inflammatory bowel disease, and can be suppressed by aggressive antibiotics treatment. The study demonstrates that inflammation-associated colon carcinogenesis can be initiated solely by intrinsic paracellular permeability barrier perturbations, and establishes that St14 is a critical tumor suppressor gene in the mouse gastrointestinal tract.

Results

Meta-analysis of transcriptomes shows decreased expression of ST14 in human colon adenomas and adenocarcinomas

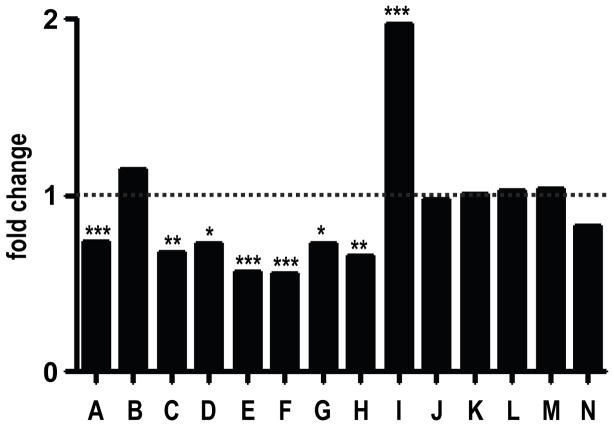

We first performed in silico data mining of the Oncomine microarray database (Rhodes et al., 2004) to corroborate the initial report of reduced ST14 expression in human colon cancer (Zhang et al., 1998) (Figure 1). Interestingly, ST14 was significantly downregulated compared to normal colon in seven of the fourteen published studies listed in the database (studies A and C–H), whereas six studies showed no change (studies B and J–N) and a single study (study I) found ST14 to be upregulated (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Of the fourteen studies, study A, which compared gene expression in colorectal dysplastic adenomatous polyps to normal colonic epithelium, was conducted using laser capture microdissected tissue (ST14 downregulation, P < 0.0006) (Gaspar et al., 2008), and therefore provided the most reliable estimate of ST14 expression in normal and dysplastic colonic epithelium.

Figure 1. Matriptase expression is downregulated in human colon adenomas and adenocarcinomas.

Expression of ST14, encoding matriptase, in 14 gene expression array studies of human colon adenomas and adenocarcinomas. Data are expressed as fold change relative to corresponding normal tissue. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for details and references.

St14-ablated colonic epithelium undergoes rapid and spontaneous malignant transformation

To specifically explore the functional consequences of intestinal loss of St14 on colon carcinogenesis, we interbred mice carrying an St14LoxP allele (List et al., 2009) with mice carrying an St14 null allele (St14−) and mice carrying a Cre transgene under the control of the intestinal-specific villin promoter (villin-Cre+) (Madison et al., 2002). This resulted in the generation of villin-Cre+/0;St14LoxP/− mice (hereafter termed St14− mice) and their associated littermates villin-Cre+/0;St14LoxP/+, villin-Cre0;St14LoxP/−, and villin-Cre0;St14LoxP/+ (hereafter termed St14+ mice). As reported recently (List et al., 2009), this strategy resulted in the efficient deletion of matriptase from the entire intestinal tract, as shown by the loss of matriptase immunoreactivity in colon (compare Supplementary Figure 1a and b) and small intestine (compare Supplementary Figure 1c and d), and by highly diminished St14 transcript abundance (Supplementary Figure 1e). St14− mice were outwardly unremarkable at birth, but displayed significant growth retardation after weaning (Supplementary Figure 1f). Examination of prospective cohorts of St14− mice and their associated littermate controls revealed that intestinal St14 ablation greatly diminished life span (Supplementary Figure 1g).

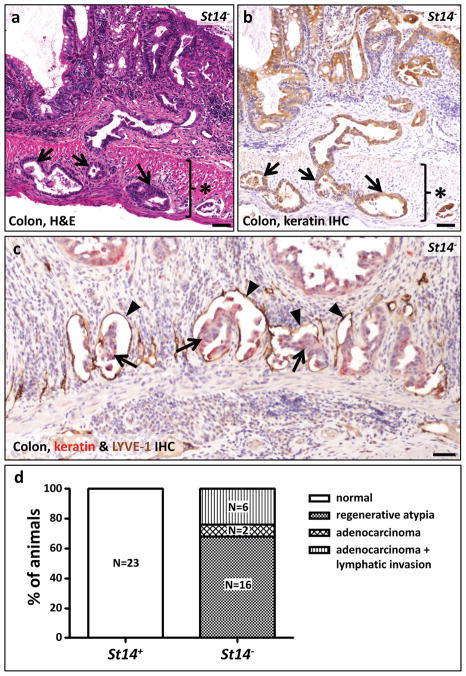

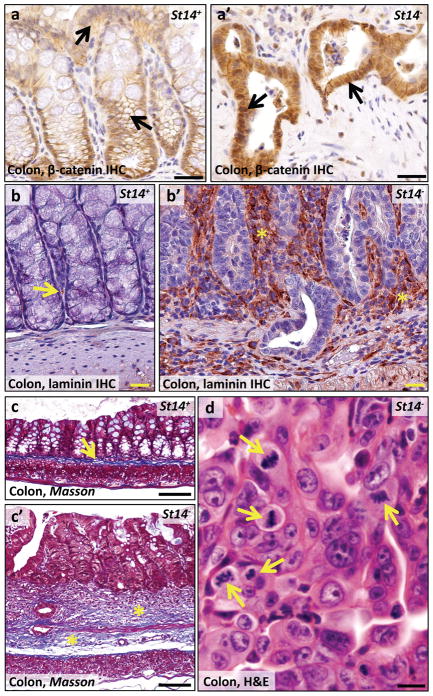

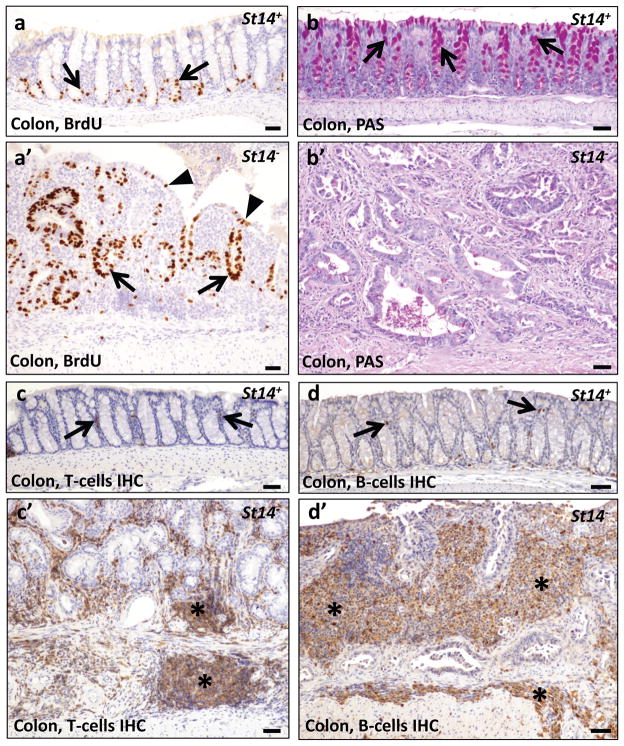

Unexpectedly, histological analysis of moribund St14− mice revealed the presence of invasive adenocarcinoma of the colon in 8 of 24 (33%) of St14− mice examined at four to 18 weeks of age (Table 1, Figure 2a, b, and d) and dysplastic colonic epithelium (regenerative atypia) in the remaining 16 mice (Table 1 and Figure 2d). Remarkably, in light of the fact that these mice were not carcinogen treated or exposed to other insults to the intestinal tract, adenocarcinoma could be found in mice less than five weeks of age (Table 1). All adenocarcinomas had progressed to invade the muscularis mucosae underlying the colonic epithelium and the subadjacent muscularis externa (Figure 2a and b). Furthermore, in six of eight (75%) adenocarcinomas examined, the tumor cells had infiltrated the lymphatic vasculature, as revealed by combined immunohistochemical staining with pan-keratin antibodies and antibodies against the lymphatic endothelial marker, LYVE-1 (Table 1 and Figure 2c and d). The tumors displayed many hallmarks of human colitis-associated colon cancer, including activation of β-catenin (Figure 3a and a′), dysorganized basement membrane deposition (Figure 3b and b′), fibrosis (Figure 3c and c′), severe dysplasia with abundant atypical mitosis (Figure 3d), epithelial hyperproliferation (Figure 4a and a′), loss of terminal differentiation (Figure 4b and b′), and chronic inflammatory cell infiltrates (Figure 4c and c′, d and d′). Importantly, the small intestine was histologically unremarkable in all mice examined (data not shown), although St14 was efficiently ablated also from this tissue (Supplementary Figure 1d and e). Taken together, these data show that St14 is a critical tissue-specific tumor suppressor gene in the mouse intestine that suppresses the formation of early, invasive adenocarcinomas of the colon.

Table 1.

Intestinal lesions in St14− mice

| Mouse | Gender | Age (days) | Diagnosis of intestinal lesions | Lymphatic invasion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCV41 | Male | 31 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV52 | Male | 33 | Adenocarcinoma | Yes |

| MCV55 | Female | 55 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV56 | Female | 55 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV59 | Male | 25 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV66 | Male | 28 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV70 | Female | 24 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV76 | Male | 129 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV127 | Male | 111 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV153 | Male | 79 | Adenocarcinoma | No |

| MCV159 | Female | 26 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV162 | Male | 105 | Adenocarcinoma | Yes |

| MCV173 | Male | 44 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV180 | Female | 131 | Adenocarcinoma | No |

| MCV192 | Male | 44 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV204 | Male | 48 | Adenocarcinoma | Yes |

| MCV234 | Male | 50 | Adenocarcinoma | Yes |

| MCV256 | Male | 56 | Adenocarcinoma | Yes |

| MCV359 | Female | 51 | Adenocarcinoma | Yes |

| MCV366 | Male | 36 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV397 | Male | 39 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV461 | Female | 30 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV468 | Male | 22 | Regenerative atypia | No |

| MCV1250 | Male | 67 | Regenerative atypia | No |

Figure 2. Rapid and spontaneous malignant transformation of St14-ablated colonic epithelium.

(a) Representative example of adenocarcinoma in the large intestine of an eight week old St14− mouse. Tumor cells invading the muscularis externa (star) are shown with arrows. (b) The epithelial origin of the tumor cells invading the muscularis externa (star) is demonstrated by immunohistochemical staining for keratin (examples with arrows). (c) Combined immunohistochemical staining for keratin in red (examples with arrows) and the lymphatic vessel marker LYVE-1 in brown (examples with arrowheads) shows invasion of malignant cells into lymphatic vessels of a seven week old St14− mouse. Scale bar for a, b, and c = 100 μm. (d) Enumeration of colonic lesions in four to 18 week old St14+ (left) and littermate St14− mice (right), showing adenocarcinoma with lymphatic invasion in 6, adenocarcinoma without lymphatic invasion in 2, and regenerative atypia in the remaining 16 St14− mice. See Table 1 for additional details.

Figure 3. Characterization of matriptase ablation-associated colon adenocarcinoma.

(a,a′) Immunohistochemical staining of eight week old St14+ (a) and littermate St14− (a′) colons for β-catenin shows a membrane-associated β-catenin localization in St14+ epithelial cells (arrows in a), as compared to cytoplasmic and nuclear localization in adenocarcinomas of St14− colons (examples with arrows in a′). (b,b′) Immunohistochemical staining for the basement membrane marker laminin in 15 week old St14+ (b) and littermate St14− (b′) mice shows the normal appearance of the basement membrane (example with arrow in b) in St14+ mice. Loss of matriptase expression leads to increased deposition of laminin (examples with stars in b′) and loss of normal structure of the basement membrane. (c,c′) Masson Trichrome staining of the colon of six week old St14+ (c) and littermate St14− (c′) mice shows connective tissue in the submucosa of a normal colon (example with arrow in c) and fibrosis of both the mucosa and submucosa of St14− colon (examples with stars in c′). (d) High magnification shows the cytological appearance of adenocarcinomas of St14− mice. Atypical mitosis is shown by arrows. Scale bar = 200 μm (a, a′,b,b′,c,c′) and 20 μm (d).

Figure 4. Characterization of matriptase ablation-associated colon adenocarcinoma.

(a,a′) BrdU staining of eight week old St14+ (a) and littermate St14− (a′) mice shows proliferation restricted to the bottom of the crypts of normal colons (examples with arrows in a). In St14− colon, proliferating cells are found both in the bottom (examples with arrows in a′) and distal parts of crypts (examples with arrowheads in a′). (b,b′) Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of mucopolysaccharides produced by differentiated goblet cells in the colon of eleven week old St14+ (b) and littermate St14− (b′) mice. Red staining shows mucin in the normal colon (arrows in b). Absence of red staining in (b′) indicates cessation of mucin production in matriptase-ablated colon. (c,c′,d,d′) Immunohistochemical staining for T-cells (c,c′) and B-cells (d,d′) in, respectively, seven and 15 week old St14+ (c, d) and littermate St14− (c′,d′) colons. Baseline levels of T-and B-cells in the lamina propria of St14+ colon (examples with arrows in d and c) and abundance of T- and B-cells in both mucosa and submucosa of St14− colons (examples with stars in c′,d′). Scale bar = 100 μm.

Impaired barrier function in St14-ablated colon

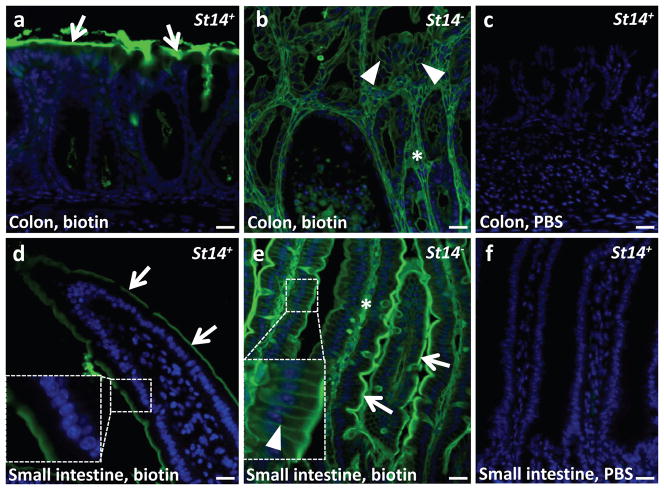

We have previously shown that either reduced matriptase expression or global postnatal ablation of matriptase from all tissues results in impaired intestinal barrier function (Buzza et al., 2010, List et al., 2009), suggesting that this would also be a feature of mice with intestinal epithelial-specific embryonic deletion of matriptase. To examine colonic and small intestinal barrier function, we injected a reactive biotin tracer into the intestinal lumen of three week old St14− and littermate St14+ mice and followed the fate of the marker using fluorescent streptavidin. Compatible with an intact intestinal barrier function, the biotin marker decorated the surface of colonic crypts and villi of the small intestine, but did not penetrate into the tissue of St14+ mice (Figure 5a and d). In contrast, just three minutes after intraluminal biotin injection, the biotin tracer could be found on the basolateral membranes and on connective tissue cells of the colon and small intestine of St14− mice demonstrating a profound failure to establish a functional intestinal barrier (Figure 5b and e).

Figure 5. Matriptase-ablated colon is leaky.

The lumen of the colon and small intestine of weaning age St14+ and littermate St14−animals was injected with Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin in PBS (a,b,d,e) or PBS (c,f). After three min, the intestine was excised, sectioned, and stained for biotin (green). Nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindol (blue). Arrows in a, d, and e show biotin bound to the surface of the mucosa. Arrowheads in b and the inset in e show biotin labeling of the basolateral membrane of polarized epithelial cells. The diffusion of biotin into intercellular space was not observed in the normal colon or small intestine (a,d, also compare insets in d and e). Stars show biotin labeling of connective tissue of both matriptase-ablated colon (b) and small intestine (e). There was no signal for biotin in colon and small intestine (c,f) injected with PBS. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Neoplastic progression occurs within a chronic inflammatory colonic microenvironment that resembles inflammatory bowel disease

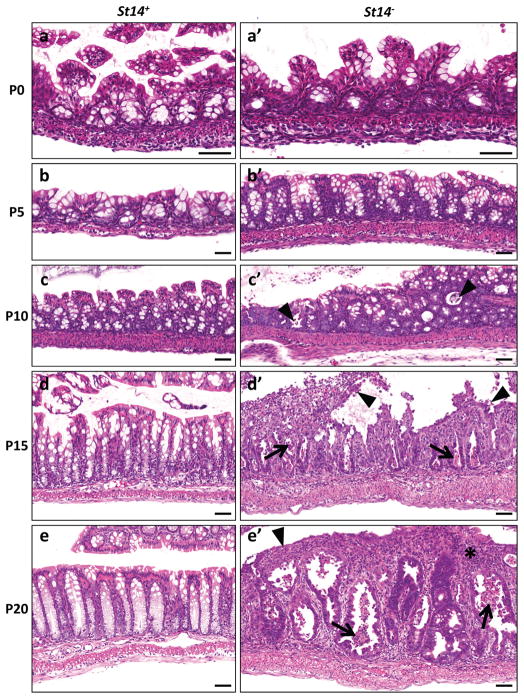

St14-ablated colonic tissue was histologically unremarkable when examined at birth and at postnatal day five (compare Figures 6a and a′, b and b′). The first observable pathological manifestation (day 10) was the detachment and apoptosis (anoikis) of distal crypt cells (compare Figure 6c and c′). This was followed by the failure of colonic epithelial cells to undergo proper terminal differentiation, as evidenced by cessation of mucin formation (data not shown). Thereafter, St14− colons entered a progressively hyperplastic inflammatory and ulcerative state that eventually resulted in the gross distortion of colonic tissue architecture (compare Figure 6d and d′, and 6e and e′). BrdU incorporating cells initially were confined to the bottom of the crypts, but later were present also in distal segments of the crypts (data not shown). Inflammatory infiltrates were evident at day 15. Inflammation at first was mild, but rapidly became severe, with inflammatory cells eventually constituting the dominant cell population of the mucosa and submucosa. Polyps were not observed in any of the examined colons prior to malignant transformation, indicating that St14 ablation-associated adenocarcinomas, like inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancers arise from flat lesions within hyperproliferative and inflamed mucosa.

Figure 6. Progressive postnatal loss of epithelial integrity of matriptase-ablated colon precedes malignant transformation.

Histological appearance of St14+ (a–e) and littermate St14− (a′-e′) colons at postnatal day 0 (a,a′), 5 (b,b′), 10 (c,c′), 15 (d,d′), and 20 (e,e′). No histological differences can be observed between normal and matriptase-ablated colon at days 0 and 5 (compare a and a′, b and b′). At day 10, St14− colons show sporadic foci of detaching and apoptotic cells (arrowheads in c′). This phenotype is significantly stronger at days 15 and 20 with extensive anoikis (arrowheads in d′), apoptotic cells (arrows in d′, e′), ulcerations (arrowhead in e′) and inflammatory cell infiltrates (star in e′). Scale bar = 100 μm.

Abnormal epithelial differentiation and activation of inflammatory pathways precede inflammatory bowel disease-like colitis and dysregulation of common colon cancer-associated signaling pathways

To elucidate the molecular events that precede the early development of colitis in mice with matriptase-ablated colonic epithelium, we next performed stage-specific transcriptomic analysis using whole-genome arrays. We selected two time points (days 0 and 5) where matriptase-ablated colonic epithelium was histologically normal, and one time point (day 10) where pathological changes were emerging (see above). The analysis was repeated four times for each of the three time points by analyzing individual St14−mice and their associated St14+ littermates. Genes that were more than two-fold up or downregulated in each of the four separate experiments were considered for analysis. No significant differences in the transcriptomes of St14-ablated and St14-sufficient colons were apparent at day 0 (data not shown). Interestingly, however, dysregulation of epithelial differentiation was apparent already at day 5 and was pronounced at day 10 (Tables 2 and 3). This was evidenced by the conspicuous upregulation of genes typically expressed in basal, suprabasal or keratinizing layers of stratified squamous epithelium lining the oral cavity, interfollicular epidermis, hair and nails of follicular epidermis, and filiform papillae of the tongue. These included keratin 14 (Krt14), keratin 36 (Krt36), keratin 84 (Krt84), small protein-rich protein 1a (Sprr1a), small protein-rich protein 2h (Sprr2h), and secreted Ly6/Plaur domain containing 1 (Slurp1). Abnormal colonic epithelial differentiation at day five was further evidenced by the downregulation of the expression of Paneth cell-specific alpha-defensin 4 (Defa4). Although St14− colonic tissues were histologically normal at day 5, activation of inflammatory pathways was evidenced by the increased expression of several inflammation-associated genes, including chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand-1 (Cxcl1), matrix metalloproteinase 10 (Mmp10), lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C2 (Ly6c2), tumor necrosis factor (Tnf), myelin and lymphocyte protein (Mal), serum amyloid A3 (Saa3), lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus I (Ly6i), lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus D (Ly6d), and GPI-anchored molecule-like protein (Gml). Inflammatory circuit activation was manifest at day 10, with upregulated expression of a number of additional inflammation-associated genes, including receptor-interacting serine-threonin kinase 3 (Ripk3), lipopolysaccharide binding protein (Lbp), lactotransferrin (Ltf), TNFAIP3 interacting protein 3 (Tnip3), secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor (Slpi), leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein 1 (Lrg1), and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 (Cxcl5). Several epithelial proliferation-associated genes also were upregulated at day 10, including genes encoding the growth factors amphiregulin (Areg), heparin binding EGF-like growth factor (Hbegf), and the p53-binding proliferation inducer, tripartite-motif containing-29 (Trim29). Taken together, the combined stage-specific histological and transcriptomic analysis show that colonic epithelial ablation of matriptase causes aberrant early postnatal epithelial differentiation that triggers expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, which in turn causes persistent inflammation and chronic epithelial hyperproliferation.

Table 2.

Genes differently regulated in 5 days old St14− mice

| Agilent Probe ID | GenBank | Regulation | Fold change1 | P-value2 | Gene symbol | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A_51_P124665 | NM_011474 | up | 17.86 | 0.001 | Sprr2h | small proline-rich protein 2H |

| A_51_P272066 | NM_025929 | up | 9.40 | 0.001 | RIKEN cDNA 2010109I03 gene | |

| A_51_P451966 | NM_001177524 | up | 5.39 | 0.035 | Gml | GPI anchored molecule like protein |

| A_52_P151240 | NM_001195732 | up | 4.34 | 0.024 | Fam150a | predicted gene, family with sequence similarity 150, member A |

| A_51_P343517 | NM_010742 | up | 3.87 | 0.027 | Ly6d | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus D |

| A_51_P363187 | NM_008176 | up | 3.13 | 0.001 | Cxcl1 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 |

| A_51_P291950 | NM_010266 | up | 2.91 | 0.037 | Gda | guanine deaminase |

| A_52_P545650 | NM_001174099 | up | 2.83 | 0.011 | Krt36 | keratin 36 |

| A_51_P187121 | NM_008127 | up | 2.63 | 0.028 | Gjb4 | gap junction protein, beta 4 |

| A_51_P411495 | XM_897643 | up | 2.50 | 0.045 | RIKEN cDNA 4930465A12 gene | |

| A_51_P420918 | NM_020498 | up | 2.39 | 0.050 | Ly6i | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus I |

| A_51_P367880 | NM_008474 | up | 2.35 | 0.037 | Krt84 | keratin 84 |

| A_51_P120830 | NM_019471 | up | 2.29 | 0.037 | Mmp10 | matrix metallopeptidase 10 |

| A_51_P385639 | NM_010291 | up | 2.28 | 0.011 | Gjb5 | gap junction protein, beta 5 |

| A_51_P337308 | NM_011315 | up | 2.27 | 0.019 | Saa3 | serum amyloid A 3 |

| A_51_P228574 | NM_146214 | up | 2.26 | 0.043 | Tat | tyrosineaminotransferase |

| A_52_P562661 | NM_010762 | up | 2.17 | 0.023 | Mal | myelin and lymphocyte protein, T-cell differentiation protein |

| A_51_P499071 | NM_010762 | up | 2.14 | 0.011 | Mal | myelin and lymphocyte protein, T-cell differentiation protein |

| A_51_P503494 | NM_018790 | up | 2.11 | 0.003 | Arc | activity regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein |

| A_52_P299446 | U90654 | up | 2.09 | 0.013 | zinc-finger domain-containing protein | |

| A_52_P220241 | AK164337 | up | 2.09 | 0.032 | RIKEN cDNA A430106P18 gene, hypothetical proline-rich region containing protein | |

| A_51_P139678 | NM_009264 | up | 2.09 | 0.021 | Sprr1a | small proline-rich protein 1A |

| A_51_P214275 | NM_001174099 | up | 2.08 | 0.023 | Krt36 | keratin 36 |

| A_51_P245090 | NM_016689 | up | 2.07 | 0.020 | Aqp3 | aquaporin 3 |

| A_51_P385099 | NM_013693 | up | 2.06 | 0.019 | Tnf | tumor necrosis factor |

| A_52_P26416 | AF106279 | up | 2.05 | 0.045 | Lamc2 | laminin gamma2 chain |

| A_52_P445360 | NM_023256 | up | 2.04 | 0.028 | Krt20 | keratin 20 |

| A_51_P197528 | NM_001099217 | up | 2.03 | 0.050 | Ly6c2 | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C2 |

| A_52_P421234 | NM_133832 | up | 2.02 | 0.011 | Rdh10 | retinol dehydrogenase 10 |

| A_51_P323195 | NM_172613 | down | 4.65 | 0.045 | Atp13a4 | ATPase type 13A4 |

| A_52_P453814 | NM_011242 | down | 3.09 | 0.045 | Rasgrp2 | RAS, guanyl releasing protein 2 |

| A_51_P394847 | NR_024599 | down | 2.86 | 0.045 | predicted gene 11346 | |

| A_51_P492940 | AK035376 | down | 2.63 | 0.045 | RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone:9530027C22, unclassifiable product | |

| A_51_P394172 | NM_007954 | down | 2.44 | 0.021 | Es1 | esterase 1 |

| A_51_P375969 | NM_053200 | down | 2.37 | 0.036 | Ces3 | carboxylesterase 3 |

| A_52_P994399 | NM_010039 | down | 2.34 | 0.048 | Defa4 | defensin, alpha, 4 |

| A_52_P115950 | AK036853 | down | 2.28 | 0.045 | RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone:9930018I23, hypothetical protein | |

| A_51_P391934 | NM_029706 | down | 2.17 | 0.050 | Cpb1 | carboxypeptidase B1 |

| A_51_P358037 | NM_001014423 | down | 2.06 | 0.045 | Abi3bp | ABI gene family, member 3 (NESH) binding protein |

| A_52_P819243 | AK049777 | down | 2.05 | 0.045 | RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone:C530048O03, hypothetical protein | |

| A_51_P242967 | NM_021308 | down | 2.01 | 0.011 | Piwil2 | piwi-like homolog 2 |

Compared to expression in normal mucosa

Student’s t-test (two-tailed, unpaired, asymptotic), Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction

Table 3.

Genes differently regulated in 10 days old St14− mice

| Agilent Probe ID | GenBank | Regulation | Fold change1 | P-value2 | Gene symbol | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A_52_P295432 | NM_009141 | up | 32.09 | 0.044 | Cxcl5 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 |

| A_51_P124665 | NM_011474 | up | 28.95 | 0.037 | Sprr2h | small proline-rich protein 2H |

| A_51_P256827 | NM_013650 | up | 9.86 | 0.044 | S100a8 | S100 calcium binding protein A8 (calgranulin A) |

| A_51_P346938 | NM_029796 | up | 8.30 | 0.044 | Lrg1 | leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein 1 |

| A_51_P363187 | NM_008176 | up | 5.02 | 0.044 | Cxcl1 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 |

| A_52_P487686 | NM_001082546 | up | 4.36 | 0.044 | cDNA sequence BC100530 | |

| A_51_P279437 | NM_029662 | up | 3.98 | 0.048 | Mfsd2a | major facilitator superfamily domain containing 2A |

| A_51_P359046 | NM_020519 | up | 3.78 | 0.044 | Slurp1 | secreted Ly6/Plaur domain containing 1 |

| A_51_P303160 | NM_007482 | up | 3.71 | 0.044 | Arg1 | arginase |

| A_51_P451966 | NM_001177524 | up | 3.58 | 0.044 | Gml | GPI anchored molecule like protein |

| A_52_P1172382 | Q8C9Z43 | up | 3.44 | 0.049 | putative uncharacterized protein | |

| A_52_P472324 | NM_011414 | up | 3.13 | 0.044 | Slpi | leukocyte peptidase inhibitor |

| A_51_P200544 | NM_001001495 | up | 3.12 | 0.044 | Tnip3 | TNFAIP3 interacting protein 3 |

| A_51_P214275 | NM_001174099 | up | 3.10 | 0.037 | Krt36 | keratin 36 |

| A_51_P187461 | NM_009044 | up | 3.03 | 0.044 | Rel | reticuloendotheliosis oncogene |

| A_51_P116609 | NM_025687 | up | 2.87 | 0.044 | Tex12 | testis expressed gene 12 |

| A_52_P531140 | NM_010416 | up | 2.81 | 0.044 | Hemt1 | hematopoietic cell transcript 1 |

| A_52_P545650 | NM_001174099 | up | 2.74 | 0.038 | Krt36 | keratin 36 |

| A_52_P31510 | NM_008814 | up | 2.65 | 0.037 | Pdx1 | pancreatic andduodenal homeobox 1 |

| A_52_P273394 | AK137552 | up | 2.58 | 0.013 | Igl-5 | Immunoglobulin lambda chain 5 |

| A_51_P272066 | NM_025929 | up | 2.57 | 0.044 | RIKEN cDNA 2010109I03 gene | |

| A_52_P116006 | NM_010266 | up | 2.57 | 0.044 | Gda | guanine deaminase |

| A_51_P225634 | NM_027306 | up | 2.50 | 0.044 | Zdhhc25 | zinc finger, DHHC domain containing 25 |

| A_52_P200286 | NM_001167746 | up | 2.46 | 0.044 | Dnahc17 | dynein, axonemal, heavy chain 17 |

| A_52_P482897 | NM_009704 | up | 2.40 | 0.044 | Areg | amphiregulin |

| A_52_P15388 | NM_008522 | up | 2.33 | 0.044 | Ltf | lactotransferrin |

| A_51_P500082 | NM_001110517 | up | 2.27 | 0.044 | predicted gene 14446 | |

| A_52_P884135 | AK085881 | up | 2.26 | 0.049 | RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone:D830023G23, unclassifiable product | |

| A_51_P165182 | NM_028967 | up | 2.25 | 0.044 | Batf2 | basic leucine zipper transcription factor, ATF-like 2 |

| A_52_P338066 | NM_023137 | up | 2.24 | 0.049 | Ubd | ubiquitin D |

| A_51_P454008 | NM_008489 | up | 2.23 | 0.037 | Lbp | lipopolysaccharide binding protein |

| A_51_P291950 | NM_010266 | up | 2.22 | 0.044 | Gda | guanine deaminase |

| A_52_P375047 | NM_009184 | up | 2.22 | 0.039 | Ptk6 | PTK6 protein tyrosine kinase 6 |

| A_51_P409349 | NM_023655 | up | 2.21 | 0.046 | Trim29 | tripartite motif-containing 29 |

| A_51_P228971 | NM_023219 | up | 2.19 | 0.044 | Slc5a4b | solute carrier family 5 (neutral amino acid transporters, system A), member 4b |

| A_51_P249989 | NM_145133 | up | 2.19 | 0.047 | Tifa | TRAF-interacting protein with forkhead-associated domain |

| A_52_P299446 | U90654 | up | 2.18 | 0.044 | zinc-finger domain-containing protein | |

| A_52_P569327 | AK045953 | up | 2.16 | 0.044 | Usp53 | mKIAA1350, ubiquitin specific peptidase 53 |

| A_52_P208213 | TC1638459 | up | 2.15 | 0.044 | kalirin-12a, partial (6%) | |

| A_51_P503494 | NM_018790 | up | 2.08 | 0.049 | Arc | activity regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein |

| A_52_P562661 | NM_010762 | up | 2.06 | 0.044 | Mal | myelin and lymphocyte protein, T-cell differentiation protein |

| A_51_P491987 | NM_019955 | up | 2.04 | 0.044 | Ripk3 | receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 3 |

| A_51_P499071 | NM_010762 | up | 2.04 | 0.044 | Mal | myelin and lymphocyte protein, T-cell differentiation protein |

| A_51_P506417 | NM_016958 | up | 2.03 | 0.044 | Krt14 | keratin 14 |

| A_51_P181565 | NM_010415 | up | 2.02 | 0.044 | Hbegf | heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor |

| A_51_P371500 | BC049570 | up | 2.00 | 0.044 | Atp8b3 | ATPase, class I, type 8B, member 3 |

| A_51_P426055 | AK048117 | down | 3.76 | 0.013 | RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone:C130035O18, unclassifiable product | |

| A_52_P506984 | ENSMUST000000449764 | down | 3.22 | 0.044 | Glyat | glycine-N-acyltransferase |

| A_52_P707475 | AK053952 | down | 2.53 | 0.044 | RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone:E230006P11, unclassifiable product | |

| A_52_P739568 | AK082480 | down | 2.17 | 0.044 | RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone:C230053P15, unclassifiable product | |

| A_52_P101443 | NM_198111 | down | 2.14 | 0.044 | Akap6 | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 6 |

Compared to expression in normal mucosa

Student’s t-test (two-tailed, unpaired, asymptotic), Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction

UniProtKB

Mouse Genome Informatics

Colonic tumor initiation in humans and animal models frequently is linked to dysregulated BMP, Notch, and Wnt signaling, leading to the expansion of the colonic stem cell population (de Lau et al., 2007, Hardwick et al., 2008, Medema and Vermeulen, 2011, Zeki et al., 2011). We therefore examined the level of expression of several putative and validated colonic stem cell markers (Aldh1a1, Ascl2, Ets2, Lgr5, Phlda1), as well as BMP (Cbfb, Dlx2, Hes1, Id1, Id2, Id3, Id4, Junb, Sox4, Stat1), Notch (Cdkn1a, Ccdn1, Cdk2, Hes1, Hes6, Klf4, Myc, Nfkb2), and Wnt (Ascl2, Axin2, Cd44, Csnk1a1, Csnk1d, Csnk1e, Ctnnb1, Cryl1, Ephb2, Ephb3, Gfi1, Hdac2, Id3, Ihh, Lef1, Myc, Nkd1, Nlk, Pascin2, Pcna, Plat, Rbbp4, Snai1, Sox4, Sox9, Spdef, Stra6, Tcf4, Yes1) target genes in St14− mice and their associated St14+ littermates (Supplementary Table 2). This transcriptomic analysis provided no clear evidence of stem cell expansion or dysregulation of either of the three signaling pathways at day 0, at day 5, when abnormal differentiation and innate immune activation were apparent, or even at day 10, when abnormal colonic morphology was manifest. In agreement with this analysis, expression of the Wnt target, Sox9, in St14− mice was appropriately confined to the crypts at day 10, and aberrant localization of Sox9 was not detected until day 15 (Supplementary Figure 2).

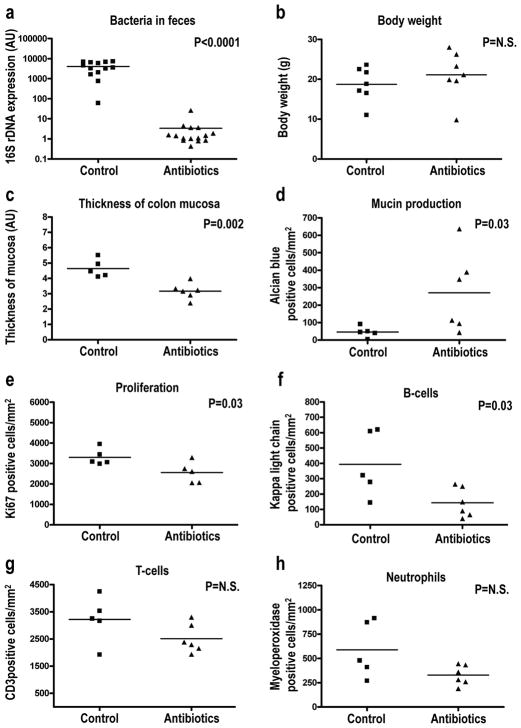

Diminution of the intestinal microbiota retards development of inflammatory bowel disease-like colitis

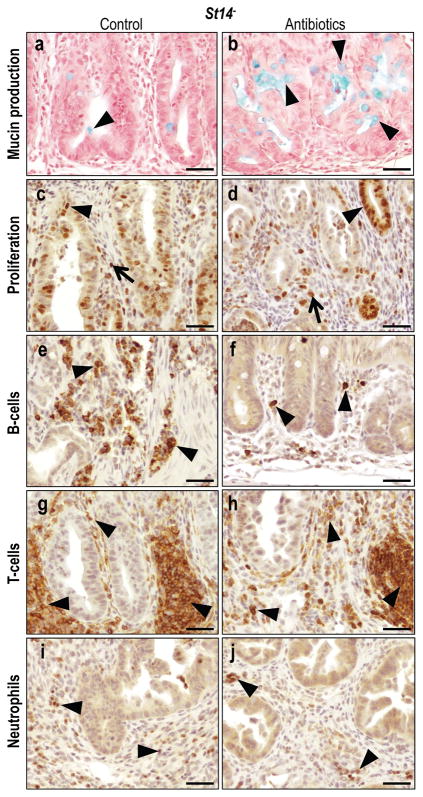

We hypothesized that the chronic inflammatory microenvironment that facilitated neoplastic progression of St14-ablated colonic epithelium was generated in part by increased exposure of the mucosal immune system to the resident microbiota due to impaired barrier formation and aberrant differentiation. To challenge this hypothesis, we next treated weaning-age St14− mice with a cocktail of the four antibiotics, ampicillin, neomycin, metronidazole, and vancomycin or with vehicle for two weeks, a standard procedure for cleansing of the intestinal microbiota (Rakoff-Nahoum et al., 2004). Due to the failure of some of the four antibiotics to be present in milk, the treatment was initiated at weaning, when significant pre-neoplastic progression was already apparent (Figure 6e and e′). As expected, antibiotics treatment reduced the colonic bacterial load by approximately 1,500-fold, as judged by the abundance of bacterial 16S ribosomal DNA in feces (Figure 7a), without compromising body weight (Figure 7b). Helicobacter is found commonly in the commensal microbiota of mice and promotes neoplastic progression in a variety of models of colon carcinogenesis (Engle et al., 2002, Erdman et al., 2003, Hale et al., 2007, Maggio-Price et al., 2006, Newman et al., 2001). We therefore specifically determined the presence of helicobacter DNA in feces of antibiotics-treated and untreated St14− mice by PCR analysis (Supplementary Table 3). Nine of 17 (53%), 7/17 (41%), and 1/17 (6%) of control mice tested were positive forHelicobacter typhlonius, Helicobacter rodentium, and an undetermined Helicobacter species, respectively, whereas 2/13 (15%) of the analyzed antibiotics-treated mice were positive for Helicobacter typhlonius. Although initiated only after weaning, antibiotics treatment markedly blunted abnormal epithelial differentiation, epithelial hyperproliferation and inflammation of the colon. This was evidenced by a quantitative reduction in colonic mucosal thickness (Figure 7c), increased mucin production (Figure 7d, Figure 8a and b), decreased epithelial proliferation (Figure 7e, Figure 8c and d), and decreased inflammatory cell infiltration (Figure 7f–h, Figure 8e–j), although the diminution of T-cell and neutrophil abundance did not reach statistical significance. Furthermore, β-catenin expression levels were normalized in two of four antibiotics-treated St14− mice when analyzed by immunoblot (Supplementary Figure 3A, compare lanes 7–10 with 13 and 14), and Sox9 was only infrequently found in the distal portion of the colonic crypts of antibiotics-treated St14− mice (Supplementary Figure 2d and e), suggesting a diminution of Wnt signaling. Analysis of BMP (phospho-SMAD1/5) and Notch1 (Notch1 intracellular domain) signaling did not reveal a treatment- or genotype-specific pattern, but the abundance of each of the two protein species in intestinal tissue extracts was difficult to assess accurately (Supplementary Figure 3B).

Figure 7. The resident microbiota contributes to preneoplastic progression of matriptase-ablated colon.

Littermate St14− mice were kept on regular water (control in a–h) or treated with a combination of ampicillin, neomycin, metronidazole, and vancomycin in the drinking water (antibiotics in a–h) for two weeks starting immediately after weaning. The animals were euthanized, the feces was used for the isolation of bacterial DNA, and the colonic tissue was subjected to quantitative histomorphometric analysis. (a) PCR quantification of 16S bacterial ribosomal DNA shows a 1 500-fold decrease in the intestinal microbiota of antibiotics treated (N=15) compared to control (N=13) mice. (b) Body weight of antibiotics treated (N=7) and control (N=7) is similar. (c) Decreased thickness of the mucosa of antibiotics treated (N=6) compared to control (N=5) mice. (d–f) Preservation of mucin production (d), decreased proliferation (e), and decreased infiltration of B-cells (f), T-cells (g) and neutrophils (h) in antibiotics treated (N=6) compared to (N=5) mice. Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s t-test (two-tailed) (a–c, e–h), and non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test (two-tailed) (d), N.S. = not significant.

Figure 8. Histological appearance of antibiotics treated matriptase-ablated colon.

(a,b) Alcian Blue staining of mucin produced by differentiated goblet cells in untreated (a) and antibiotics treated (b) St14− colons. Arrowheads point to mucin (blue). (c,d) Immunohistochemical staining for Ki67 in untreated (c) and antibiotics treated (d) St14−mice show significantly decreased rates of proliferation of both epithelial cells (arrowheads in c,d) and connective tissue cells (arrows in c,d). (e–j) Immunohistochemical staining for B-cells (e,f), T-cells (g,h), and neutrophils (i,j) in untreated (e,g,i) and antibiotics treated (f,h,j) St14− colons shows reduced chronic (examples with arrowheads in e–h) and acute (examples with arrowheads in i and j) inflammatory cell infiltration. Scale bar = 50 μm.

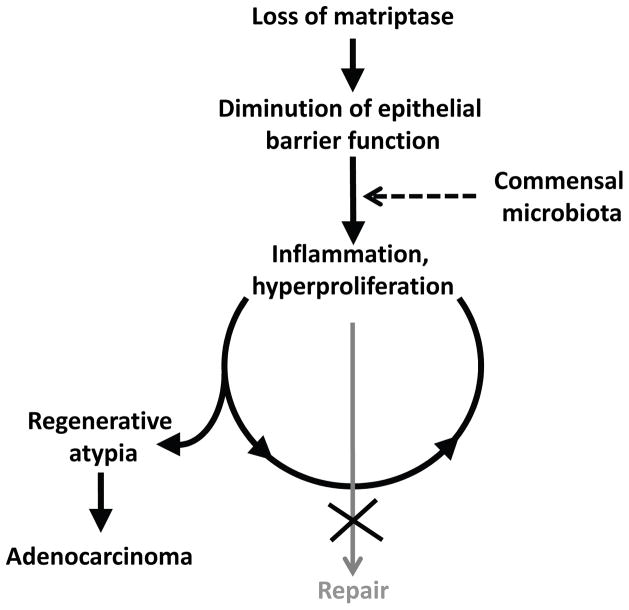

Taken together, the data are compatible with a principal role of the commensal microbiota in pre-neoplastic progression. A mechanistic model for matriptase ablation-induced colon cancer based on the above findings is shown in Figure 9. We propose that the intrinsic defect in barrier function associated with the failure to form functional tight junctions (Buzza et al., 2010, List et al., 2009) causes increased exposure of the immune system to the commensal microbiota. This exposure elicits vigorous inflammatory and repair responses that involve epithelial stem cell activation and are continuous, rather than transient, due to the inherent failure of matriptase-ablated colonic epithelial cells to establish a functional barrier. The sustained hyperproliferation of epithelial stem cells within a genotoxic chronic inflammatory microenvironment in turn induces the progressive genomic instability and subsequent rapid malignant conversion.

Figure 9. Model for matriptase ablation-induced colon carcinogenesis.

Loss of matriptase from intestinal epithelium compromises epithelial barrier function thereby causing exposure of the commensal microbiota to resident immune cells. This triggers a repair response that includes activation of local inflammatory circuits and colonic stem cell activation. This response is perpetual, rather than transient, due to the intrinsic inability of matriptase-ablated to form a functional barrier. Persistent hyperproliferation of colonic stem cells within a DNA damaging chronic inflammatory microenvironment causes the formation of adenocarcinoma.

Discussion

It has long been suspected that intrinsic alterations in the paracellular intestinal permeability barrier in humans could be a priming factor for the development of the aberrant immune response to the commensal microbiota that underlies inflammatory bowel disease and its associated malignancies. The current study now provides strong experimental support for this notion by showing that intestinal epithelial-specific ablation of matriptase - a membrane-anchored serine protease that is essential for intestinal epithelial tight junction formation - causes a commensal microbiota-dependent inflammatory bowel disease-like colitis that very rapidly progresses to adenocarcinoma. The spontaneous and rapid malignant transformation of the colonic epithelium furthermore demonstrates that a simple increase in intestinal paracellular permeability suffices to both initiate and drive inflammation-associated adenocarcinoma formation. This finding parallels the recent identification of the permeability of the epidermal barrier as a major determinant of the development of other chronic inflammatory diseases, including ichthyosis vulgaris, atopic eczema, and asthma (Sandilands et al., 2009, Smith et al., 2006). Previously published animal models of inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer include dextran sodium sulphate- or dextran sodium sulphate combined with azoxymethane-induced chemical colon carcinogenesis in inbred mouse strains (Okayasu et al., 1996, Okayasu et al., 2002), and genetic models, including germline Il10- (Berg et al., 1996), combined germline Tbx21- and Rag2- (Garrett et al., 2009), myeloid lineage Stat3- (Deng et al., 2010), myeloid lineage Itgav- (Lacy-Hulbert et al., 2007), germline Gnai2- (Rudolph et al., 1995), and combined germline Il2- and b2m-ablated mice (Shah et al., 1998). In these models, colitis and colon carcinoma occur as a consequence of either a sustained chemical damage to the colonic epithelium or perturbation of the immune system through elimination of key effectors of innate or adaptive immunity. Compared to the above models, colon carcinogenesis in intestinal St14-ablated mice appears to display some unique features. First, it is initiated by a loss of intestinal barrier function, which is associated with aberrant differentiation and immune activation, but these priming events initially occur in the absence of detectable perturbation of common colon cancer-associated signaling pathways (Kaiser et al., 2007). Second, adenocarcinoma with involvement of lymphoid tissues is observed even in very young animals. This very rapid neoplastic progression may be explained, at least in part, by the presence of various helicobacter species in the intestinal microbiota of St14− mice, as colon carcinogenesis in several mouse models has been shown to be accelerated by or to be dependent upon helicobacter colonization (Engle et al., 2002, Erdman et al., 2003, Hale et al., 2007, Maggio-Price et al., 2006, Newman et al., 2001).

In light of the findings in this study, it is tempting to speculate that neoplastic progression in previously described mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer (and perhaps colitis-associated human colorectal cancer) may be accelerated by an immune activation-induced decrease in the intestinal paracellular permeability barrier caused by downregulating the activity of matriptase or other molecules within a matriptase-dependent proteolytic pathway that facilitates tight junction formation.

Conclusive links have been forged between increased activity of multiple members of the complement of extracellular and pericellular proteases and the initiation and progression of a vide variety of human malignancies (reviewed in (Andreasen et al., 2000, Borgono and Diamandis, 2004, Kessenbrock et al., 2010, Mohamed and Sloane, 2006, Netzel-Arnett et al., 2003)). Much less studied is the capacity of extracellular/pericellular proteases to act as suppressors of tumorigenesis (reviewed in (Lopez-Otin and Matrisian, 2007, Lopez-Otin et al., 2009)). Induced germline or lineage-specific gene deletion studies in mice as well as spontaneous somatic mutation analysis of human cancers have provided direct evidence for a tumor suppressive function of MMP3 (McCawley et al., 2004, McCawley et al., 2008), MMP8 (Balbin et al., 2003, Palavalli et al., 2009), MMP12 (Acuff et al., 2006), and Cathepsin L (Reinheckel et al., 2005). Furthermore, the frequent epigenetic and genetic silencing of other extracellular and pericellular proteases in human cancers and the ability to inhibit distinct steps of tumor progression in experimental models of cancer through modulation of their level of expression suggest that the number of extracellular and pericellular proteases with tumor suppressive function may be substantial (reviewed in (Lopez-Otin and Matrisian, 2007, Lopez-Otin et al., 2009)). The current study adds matriptase to the above list of pericellular proteases with tumor suppressive functions. Matriptase, however, so far is unique among pericellular proteases in the sense that its absence by itself suffices to cause malignancy, whereas tumor suppressive function of other proteases was revealed in chemical and transplantation models of cancer.

Previous studies have shown that overexpression of matriptase can initiate carcinogenesis and accelerate the dissemination of a variety of carcinomas in diverse model systems. This property of matriptase is owed at least in part to its ability to autoactivate (Oberst et al., 2003) and subsequently serve as an initiator of several intracellular signaling and proteolytic cascades through proteolytic maturation of growth factors, protease activated receptor activation, and protease zymogen conversion (Bhatt et al., 2007, Cheng et al., 2009, Forbs et al., 2005, Ihara et al., 2002, Jin et al., 2006, Kilpatrick et al., 2006, Lee et al., 2000, List et al., 2005, Netzel-Arnett et al., 2006, Owen et al., 2010, Sales et al., 2010, Suzuki et al., 2004, Szabo et al., 2011, Takeuchi et al., 2000, Ustach et al., 2010). The dual ability of a protease to promote carcinogenesis in some contexts, while suppressing carcinogenesis in others, is rare, but not entirely unprecedented. A clear example is given by the tumor promoting effect of transgenic misexpression of the stromal protease, MMP3, in the mammary epithelial compartment, as opposed to the strong protection of mice from chemically-induced squamous cell carcinogenesis caused by germ-line ablation of the protease (McCawley et al., 2004, McCawley et al., 2008, Sternlicht et al., 1999, Sternlicht et al., 2000). Additional proteases, such as MMP9, MMP11, and MMP19 may also promote or suppress, respectively, malignant progression in a stage or tissue-dependent manner (Lopez-Otin and Matrisian, 2007).

In conclusion, our study has uncovered a critical role of the transmembrane serine protease matriptase in preserving immune homeostasis in the gastrointestinal tract and suppressing the formation of colitis and colitis-associated adenocarcinoma formation. Furthermore, the study surprisingly reveals that the simple perturbation of the epithelial permeability barrier suffices to rapidly and efficiently induce malignant transformation of colonic epithelium.

Materials and Methods

Animal experiments

All procedures involving live animals were performed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animals Care International-accredited vivarium following institutional guidelines and standard operating procedures. Within the study period, sentinels within the mouse holding room sporadically tested positive for helicobacter, murine norovirus, and mouse parvovirus, and tested negative for ectromelia virus, mouse rotavirus, Theiler’s encephalomyelitis virus (GDVII strain), lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, mycobacteria, mouse hepatitis virus, minute virus of mice, mouse polyoma virus, pneumonia virus of mice, reovirus type 3, Sendai virus, and fecal endo and ectoparasites. The NIDCR Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the study. All studies were strictly littermate controlled. St14 knock out (St14−/−) and conditional knockout (St14LoxP/LoxP) mice have been described previously (List et al., 2002, List et al., 2009). Villin-Cre+/0 [B6.SJL-Tg(Vil-Cre)997Gum/J] mice (Madison et al., 2002) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All experimental animals were in a mixed 129/C57BL6/J/NIH Black Swiss/FVB/NJ background. The genotypes of all mice were determined by PCR of ear or tail biopsy DNA. St14+ and St14LoxP alleles were detected using the primers 5′-CAGTGCTGTTCAGCTTCCTCTT-3′ and 5′-GTGGAGGTGGAGTTCTCATACG-5′. The presence of the St14 knock out allele was detected using primers 5′-GTGGAGGTGGAGTTCTCATACG-3′ and 5′-GTGCGAGGCCAGAGGCCACTTGTGTAGCG-3′. The Cre transgene was detected using the primers 5′-GCATAACCAGTGAAACAGCATTGCTG-3 ′ and 5 ′-GGACATGTTCAGGGATCGCCAGGCG-3′. For antibiotics treatment, mice were given a combination of ampicillin (1 g/l, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), neomycin (1 g/l, Sigma-Aldrich), metronidazole (1 g/l, Sigma-Aldrich), and vancomycin (0.5 g/l, Sigma-Aldrich) in the drinking water for two weeks, starting immediately after weaning (P20).

Quantitative PCR analysis

RNA was prepared from mouse organs by extraction in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), as recommended by the manufacturer. First strand cDNA synthesis was performed using oligo (dT) primers with the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). An iCycler, gene expression analysis software, and IQ SYBR Green Supermix (all from Bio-Rad Laboratories) were used for quantitative PCR analysis in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, using a primer complementary to sequence of matriptase exon 1, 5′-AACCATGGGTAGCAATCGGGGC-3′, and matriptase exon 2, 5′-AACTCCACACCCTCCTCAAAGC-3′ (annealing temperature 60 °C, denaturation temperature 95 °C, 40 cycles). Matriptase expression levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) levels in each sample. Gapdh mRNA was amplified with the primers 5′-GTGAAGCAGGCATCTGAGG-3′ and 5′-CATCGAAGGTGGAAGAGTGG-3′ (annealing temperature 60 °C, denaturation temperature 95 °C, 40 cycles).

Quantification of bacterial intestinal colonization

Bacterial DNA was isolated from feces using QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Bacterial DNA was quantified by qPCR analysis of bacterial 16S ribosomal DNA, amplified by primers: 8FM (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and Bact 5 15 R(5′-TTACCGCGGCKGCTGGCAC-3′). An iCycler, gene expression analysis software, and IQ SYBR Green Supermix were used for real-time PCR in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The thermal cycling program consisted of 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 45 s, 65 °C for 15 s and 72 °C for 15 s. Helicobacter testing was performed as described previously (Feng et al., 2005, Riley et al., 1996).

Intestinal tight junction assay

Fifty ul of 10 mg/ml EZ-Link Sulfo-NHSLC-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in PBS containing 1 mmol/L CaCl2 was injected into the lumen of distal colon and jejunum of three week old St14− and St14+ littermates that were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of an anesthetic combination (ketamine [20 mg/ml], xylazine [2 mg/ml], 50 ul/10 g). After 3 min incubation, the mice were euthanized, and the injected portion of the intestine was excised and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered zinc formalin (Z-fix, Anatech, Battle Creek, MI) for 3 h, processed into paraffin and sectioned. Five μm sections were blocked for 30 min in blocking solution (5% bovine serum albumin in PBS), and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with streptavidin Alexa Fluor 448 conjugate (Invitrogen) (5 ug/ml) in blocking solution. Sections were washed three times with PBS and mounted with VECTASHIELD HardSet Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were acquired on an Axio Imager. Z1 microscope using an AxioCam HRc/MRm digital camera (Carl Zeiss Ldt, Jena, Germany).

Histopathology

Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation. Tissues were fixed for 24 h in Z-fix, processed into paraffin, cut into 5 μm sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For visualization of mucin production, sections were stained with the Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) kit (Sigma-Aldrich) or Alcian Blue (1% Alcian Blue in 3% acetic acid). Collagen was detected using Masson-trichrome staining.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were prepared and antigens were retrieved by heating in epitope retrieval buffer (0.01 M sodium citrate, pH 6.5) or Epitop Retrieval Buffer-Reduced pH (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) for matriptase IHC. The sections were blocked for 1 h in 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich), or 10% horse serum (for matriptase IHC) in PBS, and incubated overnight at 4 C with primary antibody: matriptase (Sheep, Polyclonal, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), cytokeratins (Rabbit, Polyclonal, DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA), LYVE-1 (Goat, Polyclonal, R&D Systems), β-catenin (Rabbit, Monoclonal, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), laminin (Rabbit, Polyclonal, Sigma-Aldrich), BrdU (Rat, Monoclonal, Accurate Chemicals & Scientific, Westbury, NY), CD3 (Rabbit, Polyclonal, DakoCytomation), κ-light chain (Rabbit, Polyclonal, DakoCytomation), Ki67 (Rabbit, Polyclonal, Novocastra, Westbury, NY), myeloperoxidase (Rabbit, Polyclonal, DakoCytomation), and Sox9 (Rabbit, Polyclonal, Millipore, Temecula, CA). Bound antibodies were visualized using either biotin-conjugated horse anti-goat, goat anti-rabbit, goat anti-rat (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), rabbit anti-sheep (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), or alkaline phosphatase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (DakoCytomation) secondary antibodies and a VECTASTAIN ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate (Sigma-Aldrich) or Vulcan Fast Red Chromogen Kit 2 (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA). Hematoxylin was the counterstain.

Immunoblotting

Approximately 1 cm of the distal part of large intestine was homogenized and lysed in 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Boiled and reduced samples were subjected to immunoblotting using primary antibodies: anti-β-catenin (Rabbit, Monoclonal, Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-SMAD1/5 (Rabbit, monoclonal, Cell Signaling), anti-Notch1 (Rabbit, monoclonal, Cell Signaling), and anti-GAPDH (Rabbit, polyclonal, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA). The signal was detected with secondary anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to either alkaline phosphatase (Dako) or horseradish peroxidase (Thermo Scientific).

Microarray analysis

Microarray analysis of gene expression was performed using Mouse GE 4×44K v2 Microarray slides (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, colon tissue was dissected from four pairs of St14− and littermate St14+ mice. RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent, as recommended by the manufacturer. The quality and the integrity of the RNA was determined by the 2100 Bioanalyzer platform (Agilent Technologies). Isolated colon RNA together with Universal Mouse Reference RNA (Agilent Technologies) was labeled using the Two-color Quick Amp Labeling Kit (Agilent Technologies). Labeled RNA was hybridized to the slides overnight. After washing the slides were scanned using a High Resolution Microarray Scanner. The raw microarray image files were read and processed with Feature Extraction Software. The analysis of microarray data was performed using Gene Spring Software (all from Agilent Technologies). Gene expression was normalized to the universal reference RNA. From the original data set, only probes flagged as detected at least in one sample were selected. These data sets were further filtered for probes with 2-or more fold change in expression between St14+ and St14− tissue. Statistical analysis of these data sets led to the identification of probes with significantly different change in gene expression using unpaired Student’s t-test with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction. Probes with P < 0.05 were considered significant and are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Histomorphometric analysis

Five control St14− and six antibiotics treated St14− mice were analyzed. To determine the mucosal thickness, 2 mm of the distal colon mucosa adjacent to squamous epithelium of the rectum was identified on a H&E section and the area was calculated using Aperio ImageScope software (Aperio, Vista, CA). For the quantification of proliferation, differentiation and inflammatory infiltrates, seven individual areas of distal colon on each slide were selected for counting. The number of counts was normalized to the surface of the selected area and averaged for each individual animal.

Supplementary Material

(a–d) Representative examples of matriptase immunohistochemical analysis of epithelium of large (a,b) and small (c,d) intestine of three week old St14+ (a,c) and St14− (b,d) mice showing loss of matriptase (examples with arrows) from basolateral membranes of intestinal epithelial cells. Scale bar = 50 μm. (e) Quantitative PCR analysis of St14 mRNA levels in colon (left panel), small intestine (middle panel), and kidney (right panel) of four weaning age St14+ (left bars) and four littermate St14− (right bars) mice showing efficient Cre-mediated ablation of St14 mRNA in intestinal tissues. mRNA levels are normalized to Gapdh and are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s t-test (two-tailed), N.S. = not significant. (f) Representative example of the external appearance of St14− (left) and littermate St14+ control mouse (right) at four weeks of age showing decreased body size. (g) Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival of St14+ (N=26) and littermate St14− (N=20) mice followed for up to 80 days. Statistical significance was determined by the log-rank test, two-tailed.

Immunohistochemical staining for Sox9 in St14+ (a,b,c) and St14− (a′,b′,c′,d,e) colons at postnatal day 10 (a,a′), 15 (b,b′) and 20 (c,c′) shows appropriate localization of Sox9 in the crypts of control St14+ animals (examples with arrows in a,b,c) and a very similar signal localization in St14− animals at postnatal day 10 (example with arrow in a′). Sox9 expression becomes dysregulated at postnatal days 15 and 20, as shown by Sox9-positive cells on the top of mucosa (examples with arrowheads in b′). Antibiotics treatment of St14− mice (e) reduces aberrant Sox9 expression (compare examples with arrownheads in d and e). Scale bar = 50 μm.

Immunoblot analysis of large intestine tissue lysates of St14− (lanes 4–5, 11–14 in A, lanes 3–4, 10–13 in B) and littermate control St14+ animals (lanes 1–3, 7–10 in A, lanes 1–2, 6–9 in B) kept on regular water (lanes 1–6 in A, lanes 1–5 in B) or on antibiotics treatment (lanes 7–14 in A, lanes 6–13 in B). (A) β-catenin expression pattern shows increased signal in all non-treated St14− animals (lanes 4–6) and normal expression in two antibiotics treated St14− animals (lanes 13–14 in A). (B) Immunoblot analysis of phospho-SMAD1/5 and intracellular (NID) Notch1 domain does not reveal a treatment- or genotype- specific expression pattern. Immunoblot analysis of Gapdh expression was used as a protein loading control. Positions of molecular weight markers (kD) are shown on the right.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jerrold M. Ward, Robert D. Cardiff, and Stephen M. Hewitt for pathology advice, Drs. Vyomesh Patel and Kantima Leelahavanichkul for help with the array analysis, Dr. Myrna Mandel for helicobacter testing, and Drs. Silvio Gutkind and Mary Jo Danton for critically reviewing this manuscript. Histology was performed by Histoserv, Inc., Germantown, MD. Supported by the NIDCR Intramural Research Program (T.H.B).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests in relation to the work described.

References

- Acuff HB, Sinnamon M, Fingleton B, Boone B, Levy SE, Chen X, et al. Analysis of host- and tumor-derived proteinases using a custom dual species microarray reveals a protective role for stromal matrix metalloproteinase-12 in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7968–7975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen PA, Egelund R, Petersen HH. The plasminogen activation system in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:25–40. doi: 10.1007/s000180050497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbin M, Fueyo A, Tester AM, Pendas AM, Pitiot AS, Astudillo A, et al. Loss of collagenase-2 confers increased skin tumor susceptibility to male mice. Nat Genet. 2003;35:252–257. doi: 10.1038/ng1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg DJ, Davidson N, Kuhn R, Muller W, Menon S, Holland G, et al. Enterocolitis and colon cancer in interleukin-10-deficient mice are associated with aberrant cytokine production and CD4(+) TH1-like responses. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1010–1020. doi: 10.1172/JCI118861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt AS, Welm A, Farady CJ, Vasquez M, Wilson K, Craik CS. Coordinate expression and functional profiling identify an extracellular proteolytic signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606514104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgono CA, Diamandis EP. The emerging roles of human tissue kallikreins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:876–890. doi: 10.1038/nrc1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugge TH, Antalis TM, Wu Q. Type II transmembrane serine proteases. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23177–23181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.021006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzza MS, Netzel-Arnett S, Shea-Donohue T, Zhao A, Lin CY, List K, et al. Membrane-anchored serine protease matriptase regulates epithelial barrier formation and permeability in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4200–4205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903923107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Fukushima T, Takahashi N, Tanaka H, Kataoka H. Hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitor type 1 regulates epithelial to mesenchymal transition through membrane-bound serine proteinases. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1828–1835. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese S, Mantovani A. Inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal cancer: a paradigm of the Yin-Yang interplay between inflammation and cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:3313–3323. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lau W, Barker N, Clevers H. WNT signaling in the normal intestine and colorectal cancer. Front Biosci. 2007;12:471–491. doi: 10.2741/2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Zhou JF, Sellers RS, Li JF, Nguyen AV, Wang Y, et al. A novel mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease links mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent hyperproliferation of colonic epithelium to inflammation-associated tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:952–967. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle SJ, Ormsby I, Pawlowski S, Boivin GP, Croft J, Balish E, et al. Elimination of colon cancer in germ-free transforming growth factor beta 1-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6362–6366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SE, Poutahidis T, Tomczak M, Rogers AB, Cormier K, Plank B, et al. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes inhibit microbially induced colon cancer in Rag2-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:691–702. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63863-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Ku K, Hodzic E, Lorenzana E, Freet K, Barthold SW. Differential detection of five mouse-infecting helicobacter species by multiplex PCR. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:531–536. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.4.531-536.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbs D, Thiel S, Stella MC, Sturzebecher A, Schweinitz A, Steinmetzer T, et al. In vitro inhibition of matriptase prevents invasive growth of cell lines of prostate and colon carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:1061–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett WS, Punit S, Gallini CA, Michaud M, Zhang D, Sigrist KS, et al. Colitis-associated colorectal cancer driven by T-bet deficiency in dendritic cells. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar C, Cardoso J, Franken P, Molenaar L, Morreau H, Moslein G, et al. Cross-species comparison of human and mouse intestinal polyps reveals conserved mechanisms in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-driven tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1363–1380. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale LP, Perera D, Gottfried MR, Maggio-Price L, Srinivasan S, Marchuk D. Neonatal co-infection with helicobacter species markedly accelerates the development of inflammation-associated colonic neoplasia in IL-10(−/−) mice. Helicobacter. 2007;12:598–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick JC, Kodach LL, Offerhaus GJ, van den Brink GR. Bone morphogenetic protein signalling in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:806–812. doi: 10.1038/nrc2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara S, Miyoshi E, Ko JH, Murata K, Nakahara S, Honke K, et al. Prometastatic effect of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V is due to modification and stabilization of active matriptase by adding beta 1–6 GlcNAc branching. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16960–16967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Yagi M, Akiyama N, Hirosaki T, Higashi S, Lin CY, et al. Matriptase activates stromelysin (MMP-3) and promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:1327–1334. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser S, Park YK, Franklin JL, Halberg RB, Yu M, Jessen WJ, et al. Transcriptional recapitulation and subversion of embryonic colon development by mouse colon tumor models and human colon cancer. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R131. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:573–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick LM, Harris RL, Owen KA, Bass R, Ghorayeb C, Bar-Or A, et al. Initiation of plasminogen activation on the surface of monocytes expressing the type II transmembrane serine protease matriptase. Blood. 2006;108:2616–2623. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MG, Chen C, Lyu MS, Cho EG, Park D, Kozak C, et al. Cloning and chromosomal mapping of a gene isolated from thymic stromal cells encoding a new mouse type II membrane serine protease, epithin, containing four LDL receptor modules and two CUB domains. Immunogenetics. 1999;49:420–428. doi: 10.1007/s002510050515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy-Hulbert A, Smith AM, Tissire H, Barry M, Crowley D, Bronson RT, et al. Ulcerative colitis and autoimmunity induced by loss of myeloid alphav integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15823–15828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SL, Dickson RB, Lin CY. Activation of hepatocyte growth factor and urokinase/plasminogen activator by matriptase, an epithelial membrane serine protease. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36720–36725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Anders J, Johnson M, Sang QA, Dickson RB. Molecular cloning of cDNA for matriptase, a matrix-degrading serine protease with trypsin-like activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18231–18236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List K, Haudenschild CC, Szabo R, Chen W, Wahl SM, Swaim W, et al. Matriptase/MT-SP1 is required for postnatal survival, epidermal barrier function, hair follicle development, and thymic homeostasis. Oncogene. 2002;21:3765–3779. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List K, Szabo R, Molinolo A, Sriuranpong V, Redeye V, Murdock T, et al. Deregulated matriptase causes ras-independent multistage carcinogenesis and promotes ras-mediated malignant transformation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1934–1950. doi: 10.1101/gad.1300705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List K, Kosa P, Szabo R, Bey AL, Wang CB, Molinolo A, et al. Epithelial integrity is maintained by a matriptase-dependent proteolytic pathway. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1453–1463. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Otin C, Matrisian LM. Emerging roles of proteases in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:800–808. doi: 10.1038/nrc2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Otin C, Palavalli LH, Samuels Y. Protective roles of matrix metalloproteinases: from mouse models to human cancer. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3657–3662. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.22.9956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison BB, Dunbar L, Qiao XT, Braunstein K, Braunstein E, Gumucio DL. Cis elements of the villin gene control expression in restricted domains of the vertical (crypt) and horizontal (duodenum, cecum) axes of the intestine. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33275–33283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio-Price L, Treuting P, Zeng W, Tsang M, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Iritani BM. Helicobacter infection is required for inflammation and colon cancer in SMAD3-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:828–838. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCawley LJ, Crawford HC, King LE, Jr, Mudgett J, Matrisian LM. A protective role for matrix metalloproteinase-3 in squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6965–6972. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCawley LJ, Wright J, LaFleur BJ, Crawford HC, Matrisian LM. Keratinocyte expression of MMP3 enhances differentiation and prevents tumor establishment. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1528–1539. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema JP, Vermeulen L. Microenvironmental regulation of stem cells in intestinal homeostasis and cancer. Nature. 2011;474:318–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed MM, Sloane BF. Cysteine cathepsins: multifunctional enzymes in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:764–775. doi: 10.1038/nrc1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzel-Arnett S, Hooper JD, Szabo R, Madison EL, Quigley JP, Bugge TH, et al. Membrane anchored serine proteases: a rapidly expanding group of cell surface proteolytic enzymes with potential roles in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:237–258. doi: 10.1023/a:1023003616848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzel-Arnett S, Currie BM, Szabo R, Lin CY, Chen LM, Chai KX, et al. Evidence for a matriptase-prostasin proteolytic cascade regulating terminal epidermal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32941–32945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JV, Kosaka T, Sheppard BJ, Fox JG, Schauer DB. Bacterial infection promotes colon tumorigenesis in Apc(Min/+) mice. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:227–230. doi: 10.1086/321998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberst MD, Williams CA, Dickson RB, Johnson MD, Lin CY. The activation of matriptase requires its noncatalytic domains, serine protease domain, and its cognate inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26773–26779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304282200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okayasu I, Ohkusa T, Kajiura K, Kanno J, Sakamoto S. Promotion of colorectal neoplasia in experimental murine ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;39:87–92. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okayasu I, Yamada M, Mikami T, Yoshida T, Kanno J, Ohkusa T. Dysplasia and carcinoma development in a repeated dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis model. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1078–1083. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen KA, Qiu D, Alves J, Schumacher AM, Kilpatrick LM, Li J, et al. Pericellular activation of hepatocyte growth factor by the transmembrane serine proteases matriptase and hepsin, but not by the membrane-associated protease uPA. Biochem J. 2010;426:219–228. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palavalli LH, Prickett TD, Wunderlich JR, Wei X, Burrell AS, Porter-Gill P, et al. Analysis of the matrix metalloproteinase family reveals that MMP8 is often mutated in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:518–520. doi: 10.1038/ng.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinheckel T, Hagemann S, Dollwet-Mack S, Martinez E, Lohmuller T, Zlatkovic G, et al. The lysosomal cysteine protease cathepsin L regulates keratinocyte proliferation by control of growth factor recycling. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3387–3395. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, Ghosh D, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley LK, Franklin CL, Hook RR, Jr, Besch-Williford C. Identification of murine helicobacters by PCR and restriction enzyme analyses. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:942–946. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.942-946.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U, Finegold MJ, Rich SS, Harriman GR, Srinivasan Y, Brabet P, et al. Ulcerative colitis and adenocarcinoma of the colon in G alpha i2-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1995;10:143–150. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh M, Trinchieri G. Innate immune mechanisms of colitis and colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nri2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales KU, Masedunskas A, Bey AL, Rasmussen AL, Weigert R, List K, et al. Matriptase initiates activation of epidermal pro-kallikrein and disease onset in a mouse model of Netherton syndrome. Nat Genet. 2010;42:676–683. doi: 10.1038/ng.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandilands A, Sutherland C, Irvine AD, McLean WH. Filaggrin in the frontline: role in skin barrier function and disease. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1285–1294. doi: 10.1242/jcs.033969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S, Rosenstiel P, Albrecht M, Hampe J, Krawczak M. Genetics of Crohn disease, an archetypal inflammatory barrier disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:376–388. doi: 10.1038/nrg1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SA, Simpson SJ, Brown LF, Comiskey M, de Jong YP, Allen D, et al. Development of colonic adenocarcinomas in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1998;4:196–202. doi: 10.1097/00054725-199808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FJ, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Sandilands A, Campbell LE, Zhao Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin cause ichthyosis vulgaris. Nat Genet. 2006;38:337–342. doi: 10.1038/ng1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht MD, Lochter A, Sympson CJ, Huey B, Rougier JP, Gray JW, et al. The stromal proteinase MMP3/stromelysin-1 promotes mammary carcinogenesis. Cell. 1999;98:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81009-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht MD, Bissell MJ, Werb Z. The matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-1 acts as a natural mammary tumor promoter. Oncogene. 2000;19:1102–1113. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L, Shen L, Clayburgh DR, Nalle SC, Sullivan EA, Meddings JB, et al. Targeted epithelial tight junction dysfunction causes immune activation and contributes to development of experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:551–563. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Kobayashi H, Kanayama N, Saga Y, Lin CY, Dickson RB, et al. Inhibition of tumor invasion by genomic down-regulation of matriptase through suppression of activation of receptor-bound pro-urokinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14899–14908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo R, Bugge TH. Membrane anchored serine proteases in cell and developmental biology. Annu Rev Cell and Developmental Biology. 2011 doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154247. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]