Abstract

Purpose

Self-report is an efficient and accepted means of assessing population characteristics, risk factors, and diseases. Little is known on the validity of self-reported work-related illness as an indicator of the presence of a work-related disease. This study reviews the evidence on (1) the validity of workers’ self-reported illness and (2) on the validity of workers’ self-assessed work relatedness of an illness.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted in four databases (Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and OSH-Update). Two reviewers independently performed the article selection and data extraction. The methodological quality of the studies was evaluated, levels of agreement and predictive values were rated against predefined criteria, and sources of heterogeneity were explored.

Results

In 32 studies, workers’ self-reports of health conditions were compared with the "reference standard" of expert opinion. We found that agreement was mainly low to moderate. Self-assessed work relatedness of a health condition was examined in only four studies, showing low-to-moderate agreement with expert assessment. The health condition, type of questionnaire, and the case definitions for both self-report and reference standards influence the results of validation studies.

Conclusions

Workers’ self-reported illness may provide valuable information on the presence of disease, although the generalizability of the findings is limited primarily to musculoskeletal and skin disorders. For case finding in a population at risk, e.g., an active workers’ health surveillance program, a sensitive symptom questionnaire with a follow-up by a medical examination may be the best choice. Evidence on the validity of self-assessed work relatedness of a health condition is scarce. Adding well-developed questions to a specific medical diagnosis exploring the relationship between symptoms and work may be a good strategy.

Keywords: Self-report, Work-related illness, Work-related diseases, Validation, Occupational health

Introduction

Self-report measures on work-related diseases including health complaints, disorders, injuries, and classical occupational diseases are widely used, especially in population surveys, such as the annual Labour Force Survey in the United Kingdom HSEa (2010). These measures are also used in more specific epidemiological studies, such as the Oslo Health Study (Mehlum et al. 2006). The purpose of these studies is to estimate or compare the prevalence rate of work-related diseases in certain groups but also case finding in workers’ health surveillance. In this review, the focus is on the self-report of work-related ill health or illness in which information is used to report about the presence of work-related diseases.

It is important to realize the difference between illness and disease. Although these terms are often used interchangeably (Kleinman et al. 1978), they are not the same. Physicians diagnose and treat diseases (i.e., abnormalities in the structure and function of bodily organs and systems), whereas patients suffer illnesses (i.e., experiences of disvalued changes in states of being and in social function: the human experience of sickness). In addition, illness and disease do not stand in a one-to-one relation. Illness may even occur in the absence of disease, and the course of a disease is distinct from the trajectory of the accompanying illness. In self-reported work-related illness, the respondent should therefore not only assess whether or not he or she is suffering from an illness (i.e., having symptoms or signs of illness or illnesses) but also assess the work relatedness of this illness. This is why self-reported work-related illness represents the collective individuals’ perception of the presence of an illness and the contribution that work made to the illness rather than a medical diagnosis and formal assessment of the work relatedness of the medical condition.

Although people’s opinions about work-related illnesses can be of interest in its own right, for epidemiological and surveillance purposes it is important to know how well self-reported work-related illnesses reflect work-related diseases as diagnosed by a physician. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), work-related diseases are those diseases where work is one of several components contributing to the disease (ILO 2005). To estimate the incidence and prevalence of work-related diseases, the most robust way would be to undertake detailed etiological studies of exposed populations in which disease outcomes can be studied in relation to risk factors at work and other potential causative factors. However, this type of studies can rarely be performed on such a scale that the findings can serve as an estimate of the prevalence of several work-related diseases in larger populations. Thus, the common alternative approach is to rely on self-report by asking people whether they suffer from work-related illness using open, structured, or semi-structured interviews, or (self-administered) questionnaires.

Self-report measures are used to measure health conditions but also to obtain information on the demographic characteristics of respondents (e.g., age, work experience, education) and about the respondents’ occupational history of exposure, demands, and tasks. Sometimes self-report is the only way to gather this information because many health and exposure conditions cannot easily be observed directly; in those cases, it is not possible to know what a person is experiencing without asking them.

When using self-report measures, it is important to realize that they are potentially vulnerable to distortion due to a range of factors, including social desirability, dissimulation, and response style (Murphy and Davidshofer 1994; Lezak 1995).

For example, how people think about their illness is reflected in their illness perceptions (Leventhal et al. 1980). In general, these illness perceptions contain beliefs about the identity of the illness, the causes, the duration, the personal consequences of the illness, and the extent to which the illness can be controlled either personally or by treatment. As a result, people with the same symptoms or illness or injury can have widely different perceptions of their condition (Petrie and Weinman 2006). It is therefore clear that the validity of the information on self-reported disease relies heavily on the ability of participants to specifically self-report their medical condition.

From various studies, we know that the type of health condition may be a determinant for a valid self-report (Oksanen et al. 2010; Smith et al. 2008; Merkin et al. 2007). From comparing self-reported illness with information in medical records, these studies showed that diseases with clear diagnostic criteria (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction) tended to have higher rates of agreement than those that were more complicated to diagnose by a physician or more difficult for the patient to understand (e.g., asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, heart failure).

The self-assessment of work relatedness can be considered a part of the perception of the causes of an illness. The attribution of an illness to work may be influenced by beliefs about disease etiology, the need to find an external explanation for symptoms, or the potential for economic compensation (Sensky 1997; Plomp 1993; Pransky et al. 1999). However, contextual factors can also influence the results of self-assessed work relatedness e.g., the way the information on study objectives is presented to the participants (Brauer and Mikkelsen 2003) or the news media attention to the subject (Fleisher and Kay 2006).

When evaluating self-reported work-related ill health, it is necessary to consider (1) the validation of the self-report of symptoms, signs, or illness, being the self-evaluation of health and (2) the self-assessment of work relatedness of the illness, being the self-evaluation of causality. To do this, we can consider self-report as a diagnostic test for the existence of a work-related disease and study the diagnostic accuracy. In addition, when synthesizing data from such “diagnostic accuracy studies”, it is important to explore the influence of sources of heterogeneity across studies, related to the health condition measured, the self-report measures used, the chosen reference standard, and the overall study quality.

Our primary objective was to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the self-report of work-related illness as an indicator for the presence of a work-related disease as assessed by an expert, usually a physician, using clinical examination with or without further testing (e.g., audiometry, spirometry, and blood tests) in working populations.

The research questions we wanted to answer were:

What is the evidence on the validity of workers’ self-reported illness?

What is the evidence on the validity of workers’ self-assessed work relatedness (of their illness)?

Methods

Search methods for identification of studies

An electronic search was performed on three databases as follows: Medline (through PubMed), Embase (through Ovid), and PsycINFO (through Ovid). To identify studies, a cutoff date of 01-01-1990 was imposed, and the review was limited to articles and reports published in English, German, French, Spanish, and Dutch. To answer the research questions, a search string was built after exploring the concepts of work-related ill health, self-report, measures, validity, and reliability (details Box 1). To identify additional studies, the reference lists of all relevant studies were checked.

Box 1.

Terms used in search string

| In the search on “work-related ill health,” we used the terms “Occupational Diseases”[Mesh], “Occupational Health”[Mesh], work-related ill health, work-related illness, work-related disease(s), work-related disorders, work-related complaints, work-related symptoms |

| In the search on “self-report,” we used the terms “Self Assessment (Psychology)”[Mesh], self evaluation, self-report, self-reporting, self-reported, self assessment, self-assessed, self-administrated, self-administration |

| In the search on self-report measures, we used the terms “Questionnaires”[Mesh], “Weights and Measures/methods”[Mesh], “Interviews as Topic” [Mesh], scale(s), test(s), measure(s), measurement(s), method(s) |

| To answer the second research questions, one search was built after exploring the concepts of work-related ill health, self-report, validity/reliability |

| In the search on validity and reliability, we used the terms “Psychometrics”[Mesh], “Reproducibility of Results”[Mesh], valid, validity, reliable, reliability, compare, comparison, agree, agreement, repeatable, repeatability, test–retest, consistent, consistency |

Inclusion criteria

Types of studies

Eligible were studies in which a self-reported health condition was compared with an expert’s assessment, usually a physician’s diagnosis, based on clinical examination and/or the results of appropriate tests.

Participants

Studies had to include participants who were

working adults or adolescents (>16 year), or

workers presenting their work-related health problems in occupational health care (e.g., consulting an occupational health clinic or visiting an occupational physician or other health care worker specialized in occupational health), or

workers presenting their as such identified work-related health problems in general health care (e.g., visiting a general practitioner or medical specialist not specialized in occupational health).

Index tests and target conditions

Self-report methods or measures used had to assess any self-reported health condition (illness, disease, health symptoms or complaints, health rating) or assess the attribution of self-reported illness to work factors. We included self-administered questionnaires, single question questionnaires, telephone surveys using questionnaires, and interviews using questionnaires.

Reference standards

To establish work-related disease, the reference standard was an expert’s diagnosis. The included reference standards were defined as:

Clinical examination by a physician, physiotherapist, or registered nurse resulting in either a specific diagnosis or recorded clinical findings;

Physician’s diagnosis based on clinical examination combined with results from function(al) tests (e.g., in musculoskeletal disorders) or clinical tests (e.g., spirometry);

Results of function or clinical tests (e.g., audiometry, spirometry, blood tests, specific function tests).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of articles

In the first round, two reviewers (AL, IZ) independently reviewed all titles and abstracts of the identified publications and included all articles that seemed to meet all four inclusion criteria. In the second round, full text articles were retrieved and studies were selected if they fulfilled all four criteria. The references from each included article were checked to find additional relevant studies; if these articles were included, their references were checked as well (snowballing). To check for and improve agreement, a sample of 10 results was compared, and any disagreements were discussed and resolved in consensus meetings, if necessary, with a third reviewer (HM).

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer and checked by another. This extraction was performed using a checklist that included items on (a) the self-report measure; (b) the health condition that the instrument intended to measure; (c) the presence of an explicit question to assess the work relatedness of the health condition; (d) study type; (e) the reference standard (physician, test, or both) the self-report was compared with; (f) number and description of the population; (g) outcomes; (h) other considerations; (i) author and year; and (j) country. If an article described more than one study, the results for each individual study were extracted separately.

Assessment of method quality

The included articles were assessed for their quality by rating the following nine aspects against predefined criteria: aim of study, sampling, sample size, response rate, design, self-report before testing, interval between self-report and testing, blinding and outcome assessment (Table 1). The criteria were adapted from Hayden et al. (2006) and Palmer and Smedley (2007) to assess whether key study information was reported and the risk of bias was minimized. Articles were ranked higher if they were aimed at evaluation of self-report, well-powered, employed a representative sampling frame, achieved a highly effective response rate, were prospective or controlled, had a clear timeline with a short interval between self-report and examination, assessed outcome blinded to self-report, and had clear case definitions for self-report and outcome of examination/testing. Each of these qualities was rated individually and summarized to a final overall assessment per article translated into a quality score with a maximum of 23. We called a score high if it was 16 or higher: at least 14 points on aim of the study, sampling, sample size, response rate, design, interval, and outcome assessment combined and in addition positive scores for timeline and blinding of examiner. We called a score low if the summary score was 11 or lower. The moderate scores (12–15) are in between. The information regarding the characteristics of the studies, the quality and the results were synthesised into two additional tables (Tables 5, 6).

Table 1.

Checklist for rating of study quality

| 1 | Aim of the study | Evaluation of validity of self-report was clearly stated as one of the aims of the study | 3 | Main aim |

| 2 | Part of study or secondary analysis | |||

| 1 | Addressed in small part of study | |||

| 0 | No aim or not clearly stated | |||

| 2 | Sampling | The sampling frame and sampling procedures were clearly stated | 3 | All 3 items OK |

| 2 | 2 items OK | |||

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria were clear | 1 | 1 item OK | ||

| Able to account for all of the participants at each stage of the study | 0 | None OK | ||

| 3 | Sample size | The study was well powered; studies fell into four sizes according to their likelihood of good statistical power | 3 | >600 |

| 2 | 300–600 | |||

| 1 | 100–300 | |||

| 0 | <100 | |||

| 4 | Response rate | The response rate was satisfying | 3 | >85% |

| 2 | 70–85% | |||

| 1 | 50–69% | |||

| 0 | <50 | |||

| 5 | Design | The design was a | 3 | Prospective cohort or cross-sectional with controls |

| 2 | Case–control | |||

| 1 | Cohort or cross-sectional without controls | |||

| 0 | Not clearly designed | |||

| 6 | Timeline | Self-report before examination/testing | 1 | Yes |

| 0 | No | |||

| 7 | Interval | The interval between self-report and examination was clear and not too long to introduce significant changes in health status | 3 | Self-report immediately (same day) before examination/testing |

| 2 | Self-report within 6 w before examination/testing | |||

| 1 | Report before examination/testing without interval stated or interval > 6 w | |||

| 0 | Examination/testing before self-report | |||

| 8 | Blinding of examiner | Was the examining professional aware of the outcomes of self-report | 1 | Examiner was blinded to self-report |

| 0 | Examiner was not blinded to self-report or blinding not stated | |||

| 9 | Outcome assessment | Case definitions for self-report and outcome of examination/testing were explicit and relevant, and the study referred to assessment criteria to suggest it was repeatable. | 3 | Clear case definitions for participant and examiner and explicit stated criteria |

| 2 | Clear case definitions without criteria stated | |||

| 1 | Minimal case definitions | |||

| 0 | Or no criteria stated |

A total quality score was calculated to rate the quality of the study as high (16 or higher), moderate (12–15), or low (11 or lower)

Table 5.

Characteristics of included studies

| Reference | Self-report measure | WR | Reference standard | Population description and number of participants | Study quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal disorders | ||||||

| 1 | Åkesson et al. (1999) | NMQ 7 d/12 mo; | No | Examination on the same day measuring clinical findings and diagnoses | Sweden: 90 female dental personnel and 30 controls (medical nurses) | 20, High |

| Present pain ratings on scale | ||||||

| 2 | Bjorksten et al. (1999) | NMQ-Modified; | No | Examination on the same day by physiotherapist following a structured schedule | Sweden: 171 unskilled female workers in monotonous work in metal-working or food-processing industry | 16, High |

| Current pain rating on VAS scale; | ||||||

| Body map pain drawings | ||||||

| 3 | Descatha et al. (2007) RtS | NMQ-Upper Extremities | No | Standardized clinical examination. Positive if (1) diagnosis “proved” during clinical examination, (2) diagnosis “proved” before clinical examination (e.g., previous diagnosis by a specialist, and (3) suspected diagnosis (not all of the criteria were met in clinical examination) | France: “Repetitive task” survey (RtS) 1,757 workers in 1993–1994 and 598 workers in 1996–1997 | 17, High |

| 4 | Descatha et al. (2007) PdLS | NMQ-Upper Extremities | No | Standardized clinical examination, using an international protocol for the evaluation of work-related upper-limb musculoskeletal disorders (SALTSA) | “Pays de Loire” survey (PdLS) 2,685 workers in 2002–2003. | 17, High |

| 5 | Juul-Kristensen et al. (2006) | NMQ-Upper Extremities-Modified | No | Physiotherapist and physician performed the clinical examination and five physical function tests, all according to a standardized protocol | Denmark: 101 female computer users (42 cases, 61 controls) | 16, High |

| 6 | Kaergaard et al. (2000) | PRIM, musculoskeletal symptoms (pain, discomfort) in eight body regions | No | Examined at baseline and follow-up by 3 trained physicians using clear case definitions | Denmark: 243 female sewing machine operators: 240 at baseline; 155 at 1-year follow-up | 18, High |

| 7 | Mehlum et al. (2009) | Researcher Designed questionnaire on musculoskeletal symptoms Upper Extremities “Have you experienced pain in neck or shoulder and pain in elbow, forearm, or hand in the last month, and is this totally or partially caused by working conditions in your present or previous job?” | Yes | Occupational physicians performed clinical examination, reporting clinical findings and diagnoses. The work relatedness was assessed using the “Criteria Document for Evaluating the Work relatedness of Upper-Extremity Musculoskeletal Disorders” (SALTSA) | Norway: 217 employees in Oslo Health Study; 177 cases with self-reported work-related pain, 40 controls with self-reported non-work-related pain | 17, High |

| 8 | Ohlsson et al. (1994) | NMQ-Upper Extremities 7d/12 mo | No | Clinical findings recorded by one examiner (blinded to the answers in the self-report questionnaire), according to a standard protocol and criteria | Sweden: 165 women in either repetitive industrial work (101) or mobile and varied work (64) | 11, Low |

| 9 | Perreault et al. (2008) | Researcher Designed questionnaire | No | Physical examination was performed according to a standard protocol | France: 187 university workers (80% computer clerical workers, 11% professionals, 7% technicians), 83% female | 13, Moderate |

| 10 | Silverstein et al. (1997) | Researcher designed questionnaire | No | Clinical examination | USA: Employees of automotive plants (metal, service and engine plants); 713 baseline questionnaire; 626 baseline clinical examination, 579 follow-up clinical examination (416 in both); 357 questionnaire and clinical examination at baseline | 15, Moderate |

| Body maps | ||||||

| Questions from NMQ | ||||||

| 11 | Stål et al. (1997) | NMQ-Upper Extremities | No | Clinical examination after twelve months by a physiotherapist, blinded to the results of the questionnaire and according to a standardized protocol and criteria | Sweden: 80 female milkers (active) | 18, High |

| 12 | Toomingas et al. (1995) | Researcher Designed self-administered examination | No | Clinical examination by one of eight physicians blinded to the symptoms and results of self-examination and according to a strict protocol | Sweden: 350 participants: 79 furniture movers, 89 medical secretaries, 92 men and 90 women from a sample population | 17, High |

| 13 | Zetterberg et al. (1997) | Researcher Designed questionnaire (~NMQ) | No | Physical examination of neck, shoulder, arm, hand performed according to a protocol by the same orthopedic specialist blinded to the results of the questionnaire; specialists are reporting clinical findings | Sweden: 165 women in either repetitive industrial (101) or mobile and varied work (64) | 15, Moderate |

| Skin | ||||||

| 14 | Cvetkovski et al. (2005) | Researcher Designed questionnaire on the severity of the eczema | No | Clinical assessment by specialized dermatologist from the Danish National Board of Industrial Injuries (DNBII) registry, using the DNBII severity assessment | Denmark: 602 patients with work-related hand eczema | 18, High |

| 15 | De Joode et al. (2007) | Symptom Based Questionnaire Picture Based Questionnaire | No | Clinical examination by one of two dermatologists | Netherlands: 80 SMWF (semi-synthetic metal-working fluids)-exposed metal workers and 67 unexposed assembly workers | 15, Moderate |

| 16 | Livesley et al. (2002) | Researcher Designed questionnaire | Yes | Clinical examination by an experienced dermatologist who decided whether the skin problem was work-related based on clinical diagnosis, test results and exposure at work | UK: 105 workers in the printing industry; 45 with and 60 workers without a self-reported skin problem | 13, Moderate |

| 17 | Meding and Barregard (2001) | Researcher Designed, single question: Have you had hand eczema on any occasion during the past twelve months? | No | Diagnosis of hand eczema through common clinical practice of combined information on present and past symptoms, morphology and site of skin symptoms and course of disease | Sweden: workers with vs. without self-reported hand eczema: 105 vs. 40 car mechanics, 158 vs. 92 dentists and 10 vs. 64 office workers | 12, Moderate |

| 18 | Smit et al. (1992) | Symptom Based Questionnaire | No | Medical examination by a dermatologist within days or weeks after questionnaire using clear case definitions | Netherlands: 109 female nurses | 15, Moderate |

| Self-diagnosis of hand dermatitis | ||||||

| 19 | Susitaival et al. (1995) | Self-diagnosis single question: “Do you have a skin disease now?” | No | Clinical examination with a dermatologist. immediately after answering questionnaire | Finland: farmers, 41 with and 122 without dermatitis | 12, Moderate |

| 20 | Svensson et al. (2002) | Symptom Based Questionnaire Self-diagnosis single question: “Do you have hand eczema at the moment?” | No | Dermatologist examined their hands immediately after that without knowing the participants’ answers | Sweden: 95 patients referred for hand eczema; 113 workers (40 dentists, 73 office workers) | 18, High |

| 21 | Vermeulen et al. (2000) | Symptom Based Questionnaire | No | Medical evaluation by 1 of 2 dermatologists in same week. Case definitions of medically confirmed hand dermatitis (major/minor) clearly stated | Netherlands: 202 employees in the rubber manufacturing industry | 15, Moderate |

| Respiratory disorders | ||||||

| 22 | Bolen et al. (2007) | Measures of self-reported work aggravated asthma: | Yes | Serial peak expiratory flow (PEF) testing | USA: 95 out of 382 (25%) workers enrolled in a health plan (Health Maintenance Organisation); from 382 invited, 178 had spirometry (47%), and 138 (36%) did > 2 w PEF (peak expiratory flow) testing | 10, Low |

| Daily log on symptoms and medication use | ||||||

| Post-test telephone survey on symptoms and medication use | ||||||

| 23 | Demers et al. (1990) | Researcher Designed questionnaire on respiratory symptoms | No | Clinical examination with X-ray and pulmonary function testing | USA: 923 construction workers (union members; boilermakers, pipefitters; 71% working, 70% response) | 15, Moderate |

| 24 | Johnson et al. (2009) | Farm Health Interview Survey on lung symptoms through Telephone survey | No | Physical examination and spirometry by an occupational physician or an advanced practice registered nurse | USA: 160 farmers, working; 134 farmers completed spirometry | 12, Low |

| 25 | Kauffmann et al. (1997) | Single question: “Do you think that your bronchial or respiratory status has changed (over 12 yr)? Feels worse/better?” | No | Pulmonary function test, difference in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) over 12 years | France: 915 workers in metallurgy, chemistry, printing and flour milling | 17, High |

| Latex allergy | ||||||

| 26 | Kujala et al. (1997) | Researcher Designed questionnaire on glove-related symptoms | Yes | Clinical examination to establish the diagnosis of occupational latex allergy including positive skin prick tests or a challenge test in an occupational clinic | Finland: 32 out of 37 patients diagnosed with latex allergy; 51 out of 74 controls sampled from hospital staff, matched for age and occupation, all females | 12, Moderate |

| 27 | Nettis et al. (2003) | Researcher Designed interview on rubber glove-use symptoms | Yes | Clinical examination to establish the diagnosis of occupational latex allergy including IgE and skin prick tests | Italy: 61 out of 97 (63%) hairdressers with latex glove-related skin and/or respiratory symptoms | 12, Moderate |

| Hearing problems | ||||||

| 28 | Choi et al. (2005) | Set of screening questions | No | Pure tone audiometry | USA: 98 male farmers | 11, Low |

| RSEE | ||||||

| HEW-EHAS | ||||||

| 29 | Gomez et al. (2001) | Hearing loss questionnaire (Telephone Survey) Self-rating scale | No | Pure tone audiometry | USA: 376 farmers | 15, Moderate |

| Miscellaneous | ||||||

| 30 | Eskelinen et al. (1991) | Researcher Designed questionnaire | No | Clinical examination: cardio respiratory or musculoskeletal evaluation | Finland: 174 municipal employees: healthy (43 men, 39 women); 46 men with coronary artery disease; 46 women with lower back pain | 15, Moderate |

| 31 | Lundström et al. (2008) | Stockholm Workshop scale for grading of sensorineural disorders | Yes | Vibrotactile perception test and the Purdue Pegboard test, referred to as “quantitative sensory testing” | Sweden: 126 graduates from vocational schools: auto mechanic, construction and restaurant | 11, Low |

| 32 | Dasgupta et al. (2007) | Researcher Designed questionnaires among others on self-reported pesticide poisoning symptoms | Yes | Blood tests measuring acetylcholinesterase enzyme | Vietnam: 190 rice farmers | 14, Moderate |

HEW-EHAS health, education and welfare-expanded hearing ability scale, NMQ nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire, PRIM project on research and intervention in monotonous work, RSEE rating scare for each ear, VAS visual analogue scale, WR work-related (i.e., whether the participant was specifically asked questions on a possible relation between health impairment and work)

Data analysis and synthesis

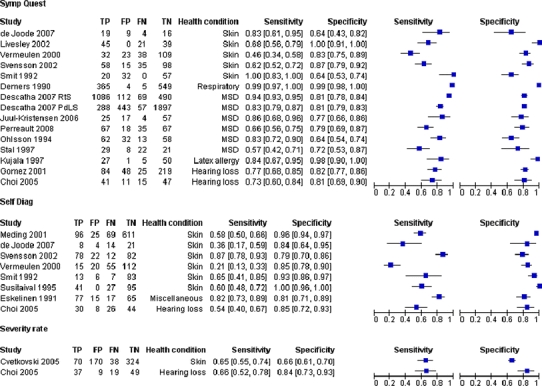

Based on the self-report measures, participants were classified as positive or negative for self-report of (work-related) illness. Based on the reference standard, the participants were classified into two groups: those with a disease, clinical findings, or positive test results and those without a disease, clinical findings, or positive test results. From the 19 studies that contained sufficient data, two-by-two tables of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), false negatives (FN), and true negatives (TN) were constructed to calculate sensitivity (SE) and specificity (SP). We presented individual study results graphically by plotting the estimates of sensitivity and specificity (and their 95% confidence intervals) in a forest plot using Review Manager 5 (Fig. 3). From the studies that contained insufficient data, we presented the data on agreement (13) or sensitivity and specificity (8) in Tables 2 and 3. All data on self-assessment of work relatedness are summarized in Table 4.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of 19 included studies, categorized by type of self-report measure. TP true positive, FP false positive, FN false negative, TN true negative. Between the brackets the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of sensitivity and specificity. The figure shows the estimated sensitivity and specificity of the study (black square) and its 95% CI (black horizontal line)

Table 2.

Summary of the agreement measures from 13 studies that contained insufficient data to include them in the forest plot

| Author, year | Health condition | Reference standard | Kappa values | % or correlation | Agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mehlum et al. (2009) | MSD upper limbs | CE | 0.16–0.34 | – | Low |

| 2 | Descatha et al. (2007) RtS | MSD upper limbs | CE | 0.45–0.77 | – | Moderate–high |

| 3 | Descatha et al. (2007) PdLS | MSD upper limbs | CE | 0.22–0.45 | – | Low–moderate |

| 4 | Perreault et al. (2008) | MSD upper limbs | CE | 0.44 | 72 | Moderate |

| 5 | Kaergaard et al. (2000) | MSD upper limbs | CE | – | 0.54–0.62 | Moderate |

| 6 | Silverstein et al. (1997) | MSD | CE | 0.23–0.47 | – | Low–moderate |

| 7 | Svensson et al. (2002) | Hand eczema | CE | 0.47–0.65 | – | Moderate–high |

| 8 | Zetterberg et al. (1997) | MSD | CE + Tests | – | Sign. corr. | Not assessable |

| 9 | Toomingas et al. (1995) | MSD upper limbs | CE + Tests | <0.20 | – | Low |

| 10 | Gomez et al. (2001) | Hearing loss | Tests | 0.55 | 80 | Moderate–high |

| 11 | Lundström et al. (2008) | Neurological symptoms | Tests | – | 58–60 | Low |

| 12 | Dasgupta et al. (2007) | Pesticide poisoning | Tests | – | ≤0.17 | Low |

| 13 | Kauffmann et al. (1997) | Respiratory disorders | Tests | – | Sign. corr. | Not assessable |

% percentage of agreement, CE clinical examination, MSD musculoskeletal disorders, PdLS pays de Loire survey, RtS repetitive task survey, Sign. corr significant correlation

Table 3.

Predictive values of self-report as compared with different reference standards from 8 studies that contained insufficient data to include them in the forest plot

| Author, year | Self-report | Reference standard | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Åkesson et al. (1999) | MSD symptoms | Clinical findings | 0.45–0.73 | 0.81–0.97 |

| Diagnoses | 0.67–0.89 | 0.55–0.89 | |||

| 2 | Bjorksten et al. (1999) | MSD symptoms | Diagnoses | 0.71–1.00 | 0.21–0.66 |

| 3 | Kaergaard et al. (2000) | MSD symptoms | Diagnoses (Myofascial pain syndrome) | 0.67–1.00 | 0.68–0.74 |

| Diagnoses (Rotator cuff syndrome) | 0.69–0.78 | 0.79–0.84 | |||

| 4 | Silverstein et al. (1997) | MSD symptoms | Clinical findings | 0.77–0.88 | 0.21–0.38 |

| 5 | Toomingas et al. (1995) | MSD findings | Clinical findings | 0–1.00 | 0.63–0.99 |

| 6 | Bolen et al. (2007) | Lung; work-related asthma exacerbation | Tests (PEF) results | 0.15–0.62 | 0.65–0.89 |

| 7 | Johnson et al. (2009) | Lung symptoms | Diagnoses | 0.33–0.89 | 0.39–0.88 |

| 8 | Nettis et al. (2003) | Latex allergy symptoms | Diagnoses | 0–1.00 | 0.72–0.88 |

MSD musculoskeletal disorders, PEF peak expiratory flow

Table 4.

Outcomes of studies in which work relatedness was assessed by self-report and/or physician assessment or test results

| Author, year | Self-reported work relatedness | Work relatedness in reference standard | Outcomes on work relatedness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mehlum et al. (2009) | Yes, musculoskeletal disorders of neck or upper extremities | Physician assessed | Positive specific agreement 76–85% |

| Negative specific agreement 37–51% | ||||

| 2 | Bolen et al. (2007) | Yes, work-exacerbated asthma | Test results | Agreement on 33% |

| 3 | Lundström et al. (2008) | Yes, vibration-related symptoms | Test results | Agreement on 58–60% |

| 4 | Dasgupta et al. (2007) | Yes, pesticide exposure-related symptoms | Test results | Correlation symptoms with test results: ≤0.17 |

| 5 | Livesley et al. (2002) | Yes, hand dermatitis symptoms | Physician assessed | Sensitivity = 0.68, Specificity = 1.00 |

| 6 | Kujala et al. (1997) | No, glove use-related skin symptoms | Physician + tests | Sensitivity = 0.84, Specificity = 0.98 when combining 1–3 skin with 2–3 mucosal symptoms |

| 7 | Nettis et al. (2003) | No, glove use-related skin and lung symptoms | Physician + tests | Predictive value for symptoms low, except for “localized contact urticaria” |

The level of agreement and the predictive value of the self-report measures in relation to expert assessments were categorized as high, moderate, or low in accordance with the predefined criteria:

For studies reporting percentage of agreement, a percentage of >85% was considered high, 70–85% was considered moderate, <70% was considered low; (Altman 1991; Innes and Straker 1999a, b; Gouttebarge et al. 2004)

- For studies that reported an assessment of concordance (e.g., kappa for categorical variables or Pearson correlation coefficients for continuous variables), the reported statistic was categorized according to the following criteria:

- Kappa values >0.6 were considered high, results between 0.6 and 0.4 were considered moderate, and kappa values <0.4 were considered low (Landis and Koch 1977)

To assess sensitivity (SE), specificity (SP) independently for each measure, a value of >85% was considered high, 70–85% was considered moderate, and <70% was considered low.

Investigation of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was investigated through analyzing the tables on level of agreement, sensitivity, and specificity and through visual examination of the forest plot of sensitivities and specificities. We also explored the effect of the overall methodological quality of the study, type of health condition, type of self-report measure, and case definition used in self-report and in the reference standard. For the construction of summary receiver operating characteristics (sROC) curves, we used a fixed effects model, mainly to explore the influence of covariates like health condition or type of self-report.

Results

Search results

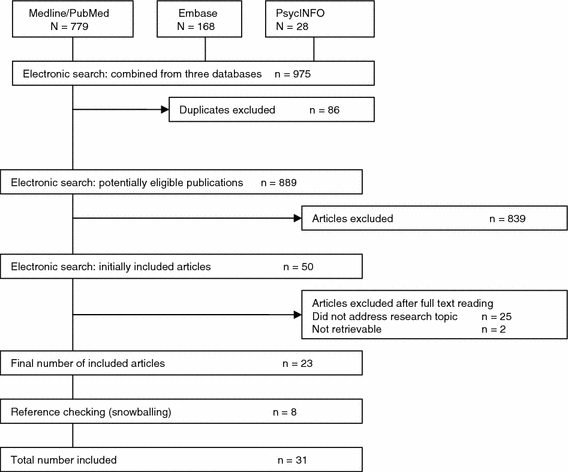

The electronic search identified 889 unique titles and abstracts, which were then screened by AL and IZ. The result was the retrieval of 50 potentially relevant articles. After assessment of the full text articles, 23 articles were included and 27 were discarded by consensus. The main reasons for exclusion being that they (1) did not address the research topic (i.e., the validity of self-reported illness among working adults), (2) did not compare self-report with expert assessment based on clinical examinations or tests, and (3) did not include an estimate of agreement between self-report and expert assessment or an estimate of the predictive value of self-report. Some articles were excluded for a combination of these reasons. (A list of excluded articles, with reasons for exclusion, is available on request.) Eight new articles were obtained by reference checking, so 31 articles in total were included in this review (Fig. 1). In the 31 articles, 32 studies were described since one article (Descatha et al. 2007) described two separate studies with different characteristics (the “Repetitive Task Survey” and the “Pays de Loire Survey”).

Fig. 1.

Search results as the number of scientific articles retrieved in the different stages of the search and selection procedure

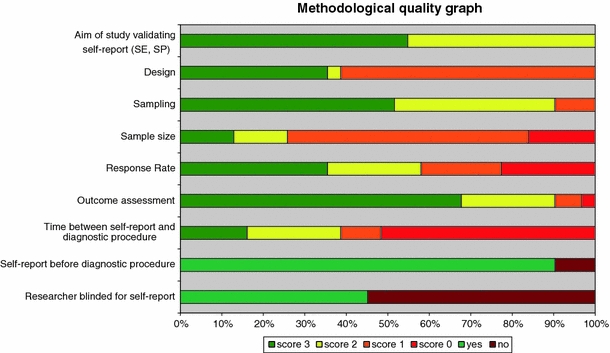

Methodological quality of included studies

The methodological quality was assessed for all 32 included studies, and the results are presented in Fig. 2. The range of the quality score was 10–20 (maximum 23) with a mean of 14.6 ± 2.6 and a median of 15. Of the studies, 11 had high quality (scores of 16 or higher), including 8 of 13 studies on musculoskeletal disorders; 15 had moderate quality (scores of 12–15), including 6 of 8 studies on skin disorders; and 6 had low quality (scores of 10 or 11).

Fig. 2.

Methodological quality graph: Review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies

Important reasons for lower study quality were a small sample size, low response rate, no control group, long interval between self-report and expert assessment, and lack of blinding to the outcomes of self-report while performing clinical examination or testing.

Characteristics of included studies

Additional Table 5 summarizes the main features of the 32 included studies, grouped according to the health condition measured: the measure/method for self-report, whether the participant was specifically asked questions on a possible relation between health impairment and work, the reference standard, the description and size of the study sample, and our quality assessment of the study.

Looking at the health conditions measured, 13 studies were aimed at musculoskeletal disorders, 8 at skin disorders, 4 at respiratory disorders, 2 at latex allergy, 2 at hearing problems, and 3 at miscellaneous problems (general health, neurological symptoms, and pesticide poisoning). In seven studies, (22%) participants were asked questions on their health as well as on their work. In four studies, participants were explicitly asked about the work relatedness of their illness or symptoms (Mehlum et al. 2009; Bolen et al. 2007; Lundström et al. 2008; Dasgupta et al. 2007). In 25 studies, the self-report was compared with the assessment by a medical expert (e.g., physician, registered nurse, or physiotherapist). In 7 studies, self-report was compared with the results of a clinical test (e.g., audiometry, pulmonary function tests, skin prick tests, blood tests).

Findings

In additional Table 6, an overview is presented of all 32 studies with the results of the comparison of self-reported work-related illness and expert assessment of work-related diseases.

Table 6.

Results on comparison of self-reported work-related illness and expert assessment of work-related diseases

| Reference | Health status | Type of self-report | Predictive values | Agreement | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Descatha et al. (2007) | MSD Upper Extremities | Symptoms | Complete analysis including all disorders at examination 1993–1994 (1757) | Complete analysis | Prevalence based on self-report > prevalence based on clinical examination |

| 1993–1994 k = 0.77 (95% CI 0.74–0.80) | ||||||

| Repetitive task Survey (RtS) | ||||||

| 1996–1997 k = 0.57 (95% CI 0.50–0.64) | ||||||

| SE = 0.94 [0.93, 0.95]; SP = 0.81 [0.78, 0.84]; PPV = 0.91; NPV = 0.88 | ||||||

| Agreement moderate to high | ||||||

| Complete analysis including all disorders at examination 1995–1996 (598) | ||||||

| SE = 0.82 [0.78, 0.86]; SP = 0.78 [0.71, 0.84]; PPV = 0.90; NPV = 0.64 | ||||||

| Sensitivity moderate to high, specificity moderate, | ||||||

| PPV high, NPV low to moderate | ||||||

| Restrictive analysis with six disorders included 1993–1994 (1757) | Restrictive analysis | |||||

| 1993–1994 k = 0.52 (95% CI 0.48–0.55) | ||||||

| 1995–1996 k = 0.45 | ||||||

| SE = 0.97 [0.95, 0.98]; SP = 0.57 [0.53, 0.60]; PPV = 0.66; NPV = 0.95 | (95% CI 0.38–0.52) Agreement moderate to high | |||||

| Restrictive analysis with six disorders included 1995–1996 (598) | ||||||

| SE = 0.87 [0.82, 0.90]; SP = 0.58 [0.52, 0.64]; PPV = 0.68; NPV = 0.80 | ||||||

| Sensitivity high, specificity low, PPV low, NPV high | ||||||

| 2 | Descatha et al. (2007) | MSD Upper Extremities | Symptoms | Extensive (including symptoms about last week and last year) | Extensive | Prevalence based on self-report > prevalence based on clinical examination |

| Standard NMQ: k = 0.22 (95% CI 0.19–0.23) Agreement low | ||||||

| Pays de Loire Survey (PdLS) | ||||||

| Standard quest. SE = 0.83 [0.79, 0.87]; SP = 0.81 [0.79, 0.83] | ||||||

| Sensitivity moderate, specificity moderate | ||||||

| Restrictive (pain scale rating (PS) and symptoms during examination) | Restrictive | |||||

| NMQ, GS > 0: k = 0.44 (95% CI 0.40–0.48) | ||||||

| NMQ, GS > 0: SE = 0.82 [0.78, 0.86]; SP = 0.82 [0.81, 0.84] | NMQ, GS ≥ 2: k = 0.45 (95% CI 0.41–0.49) Agreement moderate | |||||

| NMQ, GS ≥ 2; SE = 1.00 [0.99, 1.00]; SP = 0.51 [0.49, 0.53] | ||||||

| Sensitivity moderate to high, specificity low to moderate | ||||||

| 3 | Juul-Kristensen et al. (2006) | MSD Upper Extremities | Symptoms | SE = 0.86 [0.68, 0.96]; SP = 0.77 [0.66, 0.86] | – | |

| Sensitivity high, specificity moderate | ||||||

| 4 | Ohlsson et al. (1994) | MSD Upper extremities | Symptoms | All regions combined, related to diagnoses | – | Higher sensitivity related to diagnoses, higher specificity related to clinical findings |

| SE = 0.83 [0.72, 0.90]; SP = 0.64 [0.54, 0.74] | ||||||

| All regions combined, related to clinical findings | ||||||

| SE = 0.66 [0.57, 0.74]; SP = 0.92 [0.74, 0.99] | ||||||

| Sensitivity moderate to high, specificity low to moderate | ||||||

| 5 | Perreault et al. (2008) | MSD Upper Extremities | Symptoms | SE = 0.66 [0.56, 0.75]; SP = 0.79 [0.69, 0.87] | Agreement self-report to physicians assessment 72%; k = 0.44 (95% CI 0.31–0.56): moderate | |

| Sensitivity low, specificity moderate | ||||||

| Variable agreement when using different case definitions (symptoms, limitations ADL, limitations work, limitations leisure): k = 0.19–0.54 | ||||||

| 6 | Stål et al. (1997) | MSD Upper Extremities | Symptoms | All regions combined: SE = 0.57 [0.42, 0.71]; SP = 0.72 [0.53, 0.87] sensitivity low; specificity moderate | – | Higher sensitivity related to diagnoses, higher specificity related to clinical findings |

| For separate regions variable sensitivity and specificity for either clinical findings (SE = 52–60%, SP = 86–98%), or diagnoses (SE = 59–69%; SP = 72–90%) | ||||||

| 7 | De Joode et al. (2007) | Hand eczema | Symptoms Self-diagnosis | Symptoms Based Questionnaire (SBQ) | – | Prevalence with SBQ 2.39 times and with PBQ 2.25 times higher than reference standard prevalence |

| SE = 0.83 [0.61, 0.95]; SP = 0.64 [0.43, 0.82] | ||||||

| Self-diagnosis, with picture based questionnaire (PBQ) | ||||||

| SE = 0.36 [0.17, 0.59]; SP = 0.84 [0.64, 0.95] | ||||||

| Sensitivity low to moderate, specificity low to moderate | ||||||

| 8 | Livesley et al. (2002) | Hand eczema | Symptoms | SE = 0.68 [0.56, 0.79]; SP = 1.00 [0.91, 1.00] | – | – |

| Sensitivity low, specificity high | ||||||

| 9 | Meding and Barregard (2001) | Hand eczema | Self-diagnosis | All participants combined | – | 1-year PR 14.8–15.0% |

| SE = 0.58 [0.50, 0.66]; SP = 0.96 [0.94, 0.97] | Estimated true prevalence 30–60% higher than SR prevalence. | |||||

| Sensitivity low, specificity high | ||||||

| 10 | Smit et al. (1992) | Hand eczema | Symptoms Self-diagnosis | Symptom Based Questionnaire (SBQ) | – | Self-report prevalence based on SBQ 47.7%, on Self-diagnosis 19.4%, and on reference standard 18.3% |

| SE = 1.00 [0.83, 1.00]; SP = 0.64 [0.53, 0.74] | ||||||

| Sensitivity high, specificity low | ||||||

| Self-diagnosis SE = 0.65 [0.41, 0.85]; SP = 0.93 [0.86, 0.97] | ||||||

| Sensitivity low, specificity high | ||||||

| 11 | Susitaival et al. (1995) | Hand eczema | Self-diagnosis | Self-diagnosis | – | Self-report prevalence: 17.1% in men and 22.8% in women, reference standard prevalence 4.1% in men, 14.1% in women |

| SE = 0.60 [0.48, 0.72]; SP = 1.00 [0.96, 1.00] | ||||||

| Sensitivity low, specificity high | ||||||

| 12 | Svensson et al. (2002) | Hand eczema | Symptoms Self-diagnosis | Symptoms Based Questionnaire | Papules: k = 0.47 (0.32–0.62) | – |

| SE = 0.62 [0.52, 0.72]; SP = 0.87 [0.79, 0.92] | Erythema: k = 0.53 (0.41–0.65) | |||||

| Sensitivity low, specificity high | Vesicles: k = 0.55 (0.41–0.69) | |||||

| Self-diagnosis SE = 0.87 [0.78, 0.93]; SP = 0.79 [0.70, 0.86] | Scaling: k = 0.55 (0.44–0.66) | |||||

| Fissures: k = 0.65 (0.55–0.75) | ||||||

| Sensitivity high, specificity moderate | ||||||

| 13 | Vermeulen et al. (2000) | Hand eczema | Symptoms | ≥1 symptom, recurrent or lasted more than 3 weeks | – | Moderate sensitivity and specificity depending on case definition of positive case |

| SE = 0.46 [0.34, 0.58]; SP = 0.83 [0.75, 0.89] | ||||||

| ≥12 symptoms, recurrent or lasted more than 3 weeks | ||||||

| SE = 0.63 [0.50, 0.74]; SP = 0.75 [0.67, 0.82] | ||||||

| ≥1 symptom SE = 0.23 [0.14, 0.34]; SP = 0.89 [0.83, 0.94] | ||||||

| Symptoms at examination | ||||||

| SE = 0.21 [0.13, 0.33]; SP = 0.85 [0.78, 0.90] | ||||||

| 14 | Demers et al. (1990) | Respiratory disorders | Symptoms | SE = 0.99 [0.97, 1.00]; SP = 0.99 [0.98, 1.00] Sensitivity high, specificity high | – | – |

| 15 | Kujala et al. (1997) | Latex allergy | Symptoms |

Combining 1–3 skin with 1–3 mucosal symptoms: SE = 0.84 [0.67, 0.95]; SP = 0.98 [0.90, 1.00] Sensitivity moderate, specificity high |

– | – |

| 16 | Choi et al. (2005) | Hearing loss | Symptoms Self-diagnosis Severity rating | Self-reported screening questions: SE = 0.73 [0.60, 0.84] moderate; SP = 0.81 [0.69, 0.90] moderate | – | SE higher in younger age groups, SP higher in older age groups. |

| Self-diagnosis (Rating Scale for Each Ear, RSEE): | ||||||

| SE = 0.66 [0.52, 0.78] low; SP = 0.84 [0.73, 0.93] moderate | ||||||

| Self-rating of severity (HEW-EHAS): | ||||||

| SE = 0.54 [0.40, 0.67] low; SP = 0.85 [0.72, 0.93] high | ||||||

| 17 | Gomez et al. (2001) | Hearing loss | Symptoms | Hearing loss symptoms compared with audiometry (binaural mid-frequency) SE = 0.77 [0.68, 0.85]; SP = 0.82 [0.77, 0.86] | Hearing loss symptoms compared with audiometry (binaural mid-frequency): overall agreement 80%, k = 0.55 | Self-report prevalence hearing loss 36%; audiometric hearing impairment prevalence 9% (low-frequency), 29% (mid-frequency) and 47% (high-frequency) |

| Sensitivity moderate, specificity moderate | ||||||

| In other frequencies lower agreement | ||||||

| 18 | Eskelinen et al. (1991) | General Health | Self-diagnosis | Overall SE = 0.82 [0.73, 0.89]; SP = 0.81 [0.71, 0.89] | – | |

| Coronary artery disease (male) SE = 95.2; SP = 87.2 | ||||||

| Lower back pain (female) SE = 79.5; SP = 73.1 | ||||||

| Sensitivity moderate to high, specificity moderate to high | ||||||

| 19 | Åkesson et al. (1999) | MSD | Symptoms | Self-reported symptoms compared with clinical findings: | Higher sensitivity related to diagnoses, higher specificity related to clinical findings | |

| Neck/shoulders: SE = 73% and SP 81% moderate/moderate | ||||||

| Elbows/wrists/hands SE 50% and SP 87% low/high | ||||||

| Hips SE 45% and SP 97% low/high | ||||||

| Self-reported symptoms compared with diagnoses | ||||||

| Neck/shoulders SE 89% and SP 55% high/low | ||||||

| Elbows/wrists/hands SE 67% and SP 71% low/moderate | ||||||

| Hips SE 67% and SP 89% low/high | ||||||

| 20 | Bjorksten et al. (1999) | MSD | Symptoms Pain rating scale | SE values 71–100; highest for shoulders (100%) and neck (92%) | ||

| SP values 21–66; highest for neck (62%) and thoracic spine (66%) | ||||||

| Current ailment/pain: SE = 95% and SP = 88% | ||||||

| Sensitivity moderate to high, specificity low to moderate | ||||||

| 21 | Kaergaard et al. (2000) | MSD Upper Extremities | Symptoms | Self-reported symptoms compare to diagnosis of Myofascial pain syndrome: | Symptoms and clinical findings: | |

| r = 0.54–0.62 moderate | ||||||

| SE = 67–100%, SP = 68–74%, PPV = 31–33%, NPV = 92–93% | ||||||

| Rotator cuff tendinitis: | ||||||

| SE = 69–78%, SP = 79–84%, PPV = 16–19%, NPV = 99–100% Sensitivity low to high, specificity low to moderate | ||||||

| 22 | Mehlum et al. (2009) | MSD Upper Extremities | Symptoms, Work relatedness | Kappa values: k = 0.16–0.34 low | Prevalence of work-related illness based on self-report 6–14% higher than prevalence based on clinical examination | |

| Higher agreement on diagnoses than on findings | ||||||

| Positive specific agreement (worker and physician agreed on work relatedness) 76–85% > Negative specific agreement (worker and physician agreed on non-work relatedness) 37–51%. | ||||||

| 23 | Silverstein et al. (1997) | MSD | Symptoms | SE = 77–88%, SP = 21–38% | Self-report and physicians diagnoses: | Prevalence based on physicians’ interviews > prevalence based on self-report > physician’s diagnosis after examination |

| Sensitivity moderate to high, specificity low | Neck k = 0.43, moderate | |||||

| Shoulder k = 0.36, low | ||||||

| Elbow k = 0.47, moderate | ||||||

| Hand/wrist k = 0.42, moderate | ||||||

| Low back k = 0.23, low | ||||||

| 24 | Toomingas et al. (1995) | MSD Upper Extremities | Self-administered examination | SE = 0–100%, SP = 63–99%; PPV = 0–36%, NPV = 92–100% | Kappa values of 14 tests <0.20 | SR-prevalence 2–3 times higher than CE prevalence |

| Finger flexion deficit: k = 0.50 (0.15–0.84) | ||||||

| Highly variable sensitivity and specificity | ||||||

| Tenderness of—trapezius pars descendens: | ||||||

| k = 0.27 (0.17–0.38) | ||||||

| neck k = 0.34 (0.24–0.45) | ||||||

| Shoulders k = 0.38 (0.26–0.50) | ||||||

| 25 | Zetterberg et al. (1997) | MSD | Symptoms | A strong significant correlation between the self-reported complaints and findings on clinical examination (at the 0.001 level). | Self-report prevalence was around 50% higher than prevalence based on clinical examination | |

| Weak correlations between subjective complaints and specific tests like acromioclavicular sign or Finkelstein’s test. | ||||||

| 26 | Cvetkovski et al. (2005) | Hand eczema | Severity rating | SE = 64.8%, SP = 65.6%, PPV = 29.2%, NPV = 89.5% | Self-report prevalence 39.9% versus clinical examination prevalence 17.9% | |

| Sensitivity low, specificity low | ||||||

| 27 | Bolen et al. (2007) | Respiratory disorders Work exacerbated asthma (WEA) | Daily log or post-test survey on symptoms and medication | Post-test symptoms SE = 15% SP = 87% | Self-report prevalence WEA 48% versus prevalence based on positive PEF 14% | |

| Post-test medication use SE = 15%; SP = 89% | ||||||

| Self-reported concurrent medication use SE = 62% SP = 65% | ||||||

| Sensitivity low to moderate, specificity moderate to high | ||||||

| 28 | Johnson et al. (2009) | Respiratory disorders Obstructive respiratory disease | Symptoms | Wheeze SE = 76%, SP = 81% moderate/moderate | Sself-report prevalence 24% (95% CI 17–31%) | |

| Wheeze w/o cold SE = 50%, SP = 87% low/high | ||||||

| Chest tight at work SE = 50%, SP = 88% low/high | Prevalence based on physicians’ diagnoses 35% (95% CI 27–43%) | |||||

| Short of breath while in a hurry SE = 89%, SP = 57% high/low | ||||||

| Phlegm most days SE = 33%, SP = 85% low/moderate | ||||||

| Good–excellent health SE = 83%, SP = 39% high/moderate | ||||||

| 29 | Kauffmann et al. (1997) | Respiratory disorders | Change in health status | Self-reported: “Feels worse” and FEV1-decline over 12 years are significant related (p < 0.001) in patients with asthma and chronic bronchitis | ||

| 30 | Nettis et al. (2003) | Latex allergy | Symptoms | Localized contact urticaria SE = 100%; SP = 88% high/high | Low to high depending on symptom reported | |

| Generalized contact urticaria SE = 27%, SP = 88% low/high | ||||||

| Conjunctivitis SE = 0%, SP = 72% low/moderate | ||||||

| Rhinitis SE = 9%, SP = 76% low/moderate | ||||||

| Dyspnoea SE = 27%, SP = 84% low/moderate | ||||||

| 31 | Lundström et al. (2008) | Neurological impairment | Symptoms | About 58–60% of all individuals are graded equally by self-report and sensory tests | ||

| 32 | Dasgupta et al. (2007) | Pesticide poisoning | Symptoms | Correlation of specific blood tests with separate symptoms: P ≤ 0.17 | ||

| Correlation of specific blood test with symptom index: P = 0.05 |

GS global score, i.e., summary of pain scores on a numerical scale; HEW-EHAS health, education and welfare-expanded hearing ability scale, MSD musculoskeletal disorder, NMQ nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire, NPV negative predictive value, PPV positive predictive value, PR prevalence rate, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, SE sensitivity, SP specificity

Agreement between self-report and expert assessment

Thirteen studies presented results on the agreement between self-report and expert assessment (Table 2). The kappa values varied from <0.20 to 0.77, the percentages of agreement varied from 58 to 80%, and the correlation coefficients from <0.17 to 0.62. For two studies, only the significance of the correlation was reported, so the agreement level was not assessable. Overall, the agreement between self-reported illness and expert assessed disease was low to moderate.

Sensitivity and specificity of self-report

The results on sensitivity and specificity reflected the predictive value of self-reported illness to predict experts’ assessed disease. Nineteen studies (two studies by Descatha et al. 2007) contained enough data to combine in a forest plot (Fig. 3). The data were categorized according to the type of self-report: (1) questionnaires asking for symptoms, regardless of cutoff value (Symp Quest); (2) single-item questionnaires asking for self-diagnosis (Self Diag), and (3) scales rating severity of symptoms or illness (severity rate). Eight studies presented also data on sensitivity and specificity but did not contain enough data on true vs. false positives or negatives to include in the forest plot. These studies are summarized in Table 3.

Both the sensitivity (0–100%) and the specificity (0.21–1.00) of self-report were found to be highly variable.

Assessment of work relatedness

In seven studies, work relatedness was assessed explicitly by a physician or established with a test. In four studies (Table 4), workers were explicitly asked to self-assess one-to-one the work relatedness of their self-reported illness (Mehlum et al. 2009) or symptoms (Bolen et al. 2007; Lundström et al. 2008; Dasgupta et al. 2007).

The study by Mehlum et al. (2009) was the only study that explicitly measured agreement between self-reported and expert-assessed work relatedness. Workers with neck, shoulder, or arm pain in the past month underwent an examination at the Norwegian Institute of Occupational Health. Prior to this health examination, they answered a questionnaire on work relatedness. The positive specific agreement (proportion of positive cases for which worker and physician agree) was 76–85%; the negative specific agreement (proportion of negative cases for which worker and physician agree) was 37–51%. Bolen et al. (2007) found that self-report of work-related exacerbation of asthma was poor in patients already diagnosed with asthma. Only one-third of the self-reported symptoms could be corroborated with serial peak expiratory flow findings. Lundström et al. (2008) found that just over half of all individuals vocationally exposed to hand--arm vibration at work were graded equally by self-reported symptoms and sensory loss testing. In addition, Dasgupta et al. (2007) tested whether self-reported symptoms of poisoning were useful as an indicator of acute or chronic pesticide poisoning in pesticide-exposed farmers. They found very low agreement between symptoms of pesticide poisoning and the results of blood tests measuring acetylcholinesterase enzyme activity.

In three studies, the outcomes were only compared on a group level (Nettis et al. 2003; Kujala et al. 1997; Livesley et al. 2002). In two studies on latex allergy in workers who used gloves during work the sensitivity and specificity of single symptoms/signs (e.g., contact urticaria, dyspnoea, conjunctivitis, and rhinitis) were mainly low to moderate, except for the very specific sign of localized contact urticaria (Nettis et al. 2003) and an aggregated measure combining the self-report of at least one skin symptom/sign with one mucosal symptom/sign (Kujala et al. 1997).

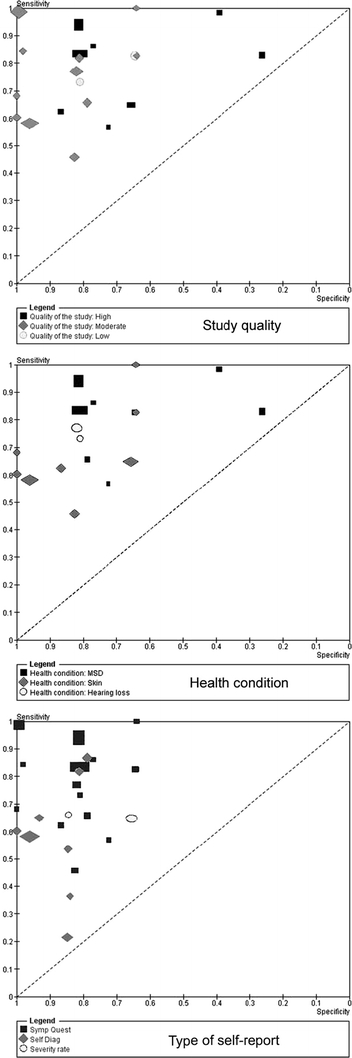

Investigation of heterogeneity

To explore the sources of heterogeneity across studies, the influence of the overall methodological quality of the study, the type of health condition measured, and the characteristics of the self-report measure were investigated using summary ROC (sROC) plots of those studies that contain enough data to include them in the forest plot.

In the sROC plot on overall quality of the studies, a comparison is made between 8 studies of high quality, 10 studies of moderate quality, and 2 studies of low quality. Again the results are highly variable, with a slight advantage for studies of moderate quality over studies with high or low quality (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Summary ROCs to explore heterogeneity based on overall study quality, type of health condition, and type of self-report measure

In the sROC plot on the type of health condition, a comparison is made between the results of 8 symptom questionnaires on musculoskeletal disorders (MSD), 8 on skin disorders, and 2 on hearing loss. Although the outcomes were highly variable, the combined sensitivity and specificity of symptom questionnaires on skin disorders was slightly better than for symptom questionnaires on musculoskeletal disorders and hearing loss. However, there were only a few self-report measures with a optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity.

In the sROC plot on type of self-report measure, a comparison is made between the results for 15 symptom questionnaires (i.e., questionnaires reporting symptoms of illness such as aches, pain, cough, dyspnoea, or itch), eight self-diagnostic questionnaires, (i.e., usually a single question asking whether the respondent suffered from a specified illness or symptom in a certain time frame), and two measures rating the severity of a health problem (i.e., how do you rate your hearing loss on a scale from 1 to 5). Although again the outcomes were highly variable, the combined sensitivity and specificity of symptom-based questionnaires was slightly better than for self-diagnosis or than for severity rating. In addition, symptom-based questionnaires tended to have better sensitivity, whereas self-diagnosis questionnaires tended to have better specificity.

Another source of heterogeneity may come from the variety in case definitions used in the studies for both self-report and reference standard. In the large cohorts of Descatha et al. (2007), the agreement differed substantially depending on the definition of a “positive” questionnaire result. If the definition was extensive (i.e., “at least one symptom in the past 12 months”), the agreement between the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ) and clinical examination was low. With a more strict case definition (i.e., requiring the presence of symptoms at the time of the examination), the agreement with the outcomes of clinical examination was higher. Comparable results on the influence of case definition were reported by Perreault et al. (2008) and Vermeulen et al. (2000). Looking at the influence of heterogeneity in the reference standard, it showed that comparison of self-report with clinical examination seemed to result in mainly moderate agreement, whereas comparison of self-report with test results was low for exposure-related symptoms and tests (Lundström et al. 2008; Dasgupta et al. 2007) and moderate for hearing loss (Gomez et al. 2001) and self-rated pulmonary health change (Kauffmann et al. 1997).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Although the initial aim of the review was to come up with an overall judgment of the validity of self-reported work-related illness by workers, the number of studies that presented results on the validity of self-reported work-related illness as an integrated concept was low. That is why we chose to analyze both elements of the integrated concept separately i.e., the validity of self-reported illness as well as the validity of the self-assessed work relatedness. Workers’ self-report is compared with expert assessment based on clinical examination and clinical testing. We included 31 articles describing 32 studies in the review. The 32 studies did not comprise the full spectrum of health conditions. Musculoskeletal disorders (13), especially of the upper limbs, and hand eczema (8) were the health conditions most frequently studied, so the generalizability of the results of this review on self-reported illness is limited to these health conditions.

On the validity of self-reported illness, we considered the level of agreement between self-report and expert assessment in 13 studies. We found that agreement was mostly low to moderate. The best agreement was found between self-reported hearing loss and the results of pure tone audiometry. For musculoskeletal and skin disorders, however, the agreement was mainly moderate.

Looking at sensitivity and specificity in studies that used the self-reporting of symptoms to predict the result of expert assessment, we often found a moderate-to-high sensitivity, but a moderate-to-low specificity. In studies that used a “single question” for self-reported health problems, the opposite was often found a high specificity combined with a low sensitivity. The sensitivity and specificity for reporting of individual symptoms was variable, but mainly low to moderate, except for symptoms that were typical for a certain disease (e.g., localized urticaria in latex allergy and breathlessness in chronic obstructive lung disease).

Seven studies also considered the work relatedness of the health condition. In five studies, workers were asked about the work-relatedness of their symptoms; in the other two studies, only the expert considered work relatedness. Surprisingly, only one (Mehlum et al. 2009) studied the agreement between self-reported work relatedness and expert assessed work relatedness. They found that workers and occupational physicians agreed more on work-related cases than on non-work-related cases. Overall, the self-assessment of work relatedness by workers was rather poor when compared with expert judgement and testing.

Limitations of the review

This review has some limitations from a methodological point of view. We considered it unlikely that important high-quality studies were overlooked because we searched several databases using a broad selection of terms referring to self-report and work relatedness and checked the references of selected studies. However, our search did not, for example, encompass the “non-peer review” (gray) literature and publications in languages other than English, French, German, Spanish, and Dutch. In addition, we only included studies published after 1-1-1990 because we chose to focus on new evidence. But we trust that our "snowballing” approach would have found the most relevant studies published before that date. We did not approach authors who are currently active in the field.

As a number of the retrieved studies did not contain enough information on true and false positives and negatives, we did not include their data in the forest plot on sensitivity and specificity. After an exploration of several potentially important sources of heterogeneity, such as the overall methodological quality of the study, the health condition measured, the type of self-report measure, and the case definitions for both self-report and reference standard, we decided that a formal meta-analysis synthesizing all data was not possible as the studies were too heterogeneous.

An important methodological consideration is that the reference standard of expert assessment may not be completely independent of the worker’s self-report. The patient’s history taken by a physician or other medical expert in the consultation room along with the clinical examination and/or tests will overlap the symptoms, signs, and illness reported by the worker during self-report. This may lead to bias often referred to as common method variance, also called mono-method bias or same source bias (Spector 2006): Correlations between variables measured with the same method might be inflated. Besides from the fact that in the studies of this review information on self-report and reference standard are only partly stemming from the same source, opinions also differ about the likely effects and on what can be done to remedy potential problems. Spector and Brannick (2010) concluded that “certainty can only be approached as a variety of methods and analyses are brought to bear on a question, hopefully all converging on the same conclusion.” This was in line with the methodological remarks on diagnostic accuracy testing in the absence of a gold standard (Bossuyt et al. 2003; Rutjes et al. 2007; Reitsma et al. 2009). Since we studied self-reported work-related illness as a form of a “diagnostic test”, the evaluation would be determining its diagnostic accuracy: the ability to discriminate between suffering or not from a health condition. Usually, a test is compared with the outcomes of a gold standard that ideally provides an error-free classification of the presence or absence of the target health condition. For most health conditions, however, a gold standard without error or uncertainty is not available (Rutjes et al. 2007). In these circumstances, researchers use the best available practicable method to determine the presence or absence of the target condition, a method referred to as “reference standard” rather than gold standard (Bossuyt et al. 2003). If even an acceptable reference standard does not exist, clinical validation is an alternative approach (Reitsma et al. 2009). In a validation study, the index test results are compared with other pieces of information, none of which are necessarily a priori supposed to identify the target condition without error. These pieces of information can come from the patient’s history, clinical examination, imaging, laboratory or function tests, severity scores, and events during follow-up. This makes validation a gradual process to assess the degree of confidence that can be placed on the results of the index test results. Since the most often used reference standard for the diagnostic accuracy of self-reported illness in the included studies is “a physician’s diagnosis”, our results may contribute to the validation of self-reported work-related illness rather than prove its validity.

Our results compared with other reports

Although there are many reviews on self-report, to our knowledge there have been neither reviews evaluating self-reported illness in the occupational health field nor reviews evaluating self-assessed work relatedness. However, there have been several validation studies on self-report as a measure of prevalence of a disease in middle-aged and elderly populations, supporting the accuracy of self-report for the lifetime prevalence of chronic diseases. For example, good accuracy for diabetes and hypertension and moderate accuracy for cardiovascular diseases and rheumatoid arthritis have been reported (Haapanen et al. 1997; Beckett et al. 2000; Merkin et al. 2007; Oksanen et al. 2010). In addition, self-reported illness was compared with electronic medical records by Smith et al. (2008) in a large military cohort; a predominantly healthy, young, working population. For most of the 38 studied conditions, prevalence was found to be consistently lower in the electronic medical records than by self-report. Since the negative agreement was much higher than the positive agreement, self-report may be sufficient for ruling out a history of a particular condition rather than suitable for prevalence studies.

Oksanen et al. (2010) studied self-report as an indicator of both prevalence and incidence of disease. Their findings on incidence showed a considerable degree of misclassification. Although the specificity of self-reports was equally high for the prevalence and incidence of diseases (93–99%), the sensitivity of self-report was considerably lower for the incident (55–63%) than the prevalent diseases (78–96%). They proposed that participants may have misunderstood or forgotten the diagnosis reported by the physician, may have lacked awareness that a given condition was a definite disease, or may have been unwilling to report it. Reluctance to report was also found when screening flour-exposed workers with screening questionnaires (Gordon et al. 1997). They found with the use of self-report questionnaires a considerable underestimation of the prevalence of bakers’ asthma. One of the reasons was that 4% of the participants admitted falsifying their self-report when denying asthmatic symptoms because they wanted to avoid a medical investigation that would lead to a change of job.

Implications for practice

Self-report measures of a work-related illness are used to estimate the prevalence of a work-related disease and the differences in prevalence between populations, such as different occupational groups representing different exposures. From this review, we know that prevalence estimated with symptom questionnaires was mainly higher than prevalence estimated with the reference standards, except for hand eczema and respiratory disorders. If prevalence was estimated with self-diagnosis questionnaires, questionnaires that use a combined score of health symptoms, or for instance use pictures to identify skin diseases, they tended to agree more with the prevalence based on the reference standard.

The choice for a certain type of questionnaire depends also on the expected prevalence of the health condition in the target population. If the expected prevalence in the target population is high enough (e.g., over 20%), a self-report measure with high specificity (>0.90) and acceptable sensitivity (0.70–0.90) may be the best choice. It will reflect the “true” prevalence because it will find many true cases with a limited number of false negatives. But if the expected prevalence is low (e.g., under 2%), the same self-report measure will overestimate the “true” prevalence considerably; it will successfully identify most of the non-cases but at the expense of a large number of false positives. This holds equally true if self-report is used for case finding in a workers’ health surveillance program. Therefore, when choosing a self-report questionnaire for this purpose, one should also take into account other aspects of the target condition, including the severity of the condition and treatment possibilities. If in workers’ health surveillance it is important to find as many cases as possible, the use a sensitive symptom-based self-report questionnaire (e.g., the NMQ for musculoskeletal disorders or a symptom-based questionnaire for skin problems) is recommended, under the condition of a follow-up including a medical examination or a clinical test able to filter out the large number of false positives (stepwise diagnostic procedure).

Although the agreement between self-assessed work relatedness and expert assessed work relatedness was rather low on an individual basis, workers and physicians seemed to agree better on work relatedness compared with the non-work relatedness of a health condition. Adding well-developed questions to a specific medical diagnosis exploring the relationship between symptoms and work may be a good strategy.

Implications for research

In the validation of patients’ and workers’ self-report of symptoms, signs, or illness, it is necessary to find out more about the way sources of heterogeneity like health condition, type of self-report, and type of reference standard influence the diagnostic accuracy of self-report. To improve the quality of field testing, we recommend the use of self-report measures with proven validity, although we realize these evidence-based questionnaires might not be available for many health conditions.

To gain more insight into the processes involved in workers’ inference of illness from work, more research is needed. One way to study the possible enhancement of workers’ self-assessment is by developing and validating a specific module with a variety of validated questions on the issue of work relatedness as experienced by the worker. Such a "work-relatedness questionnaire"(generic or disease specific) may explore (1) the temporal relationship between exposure and the start or deterioration of symptoms, (2) the dose–response relationship reflected in the improvement of symptoms away from work and/or deterioration of symptoms if the worker carries out specific tasks or works in exposure areas, and (3) whether there are colleagues affected by the same symptoms related to the same exposure (Bradford Hill 1965; Lax et al. 1998; Agius 2000; Cegolon et al. 2010). The exploration of issues such as reactions on high non-occupational exposure and the issue of susceptibility may be added as well. After studying the validity and reliability of such a specific module, it could be combined into a new instrument with a reliable and valid questionnaire on self-reported (ill) health.

Acknowledgments

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE), United Kingdom, is thanked for funding this research. The funders approved the study design but had no role in the data collection, analysis, the decision to publish or the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare not having any competing interests.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Agius R (2000) Taking an occupational history. Health environment & work 2000 (http://www.agius.com/hew/resource/occhist.htm) (updated in April 2010; accessed on 28 December 2010)

- Åkesson I, Johnsson B, Rylander L, Moritz U, Skerfving S. Musculoskeletal disorders among female dental personnel–clinical examination and a 5-year follow-up study of symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1999;72(6):395–403. doi: 10.1007/s004200050391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett M, Weinstein M, Goldman N, Yu-Hsuan L (2000) Do health interview surveys yield reliable data on chronic illness among older respondents? Am J Epidemiol 151(3):315–323 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bjorksten MG, Boquist B, Talback M, Edling C. The validity of reported musculoskeletal problems. A study of questionnaire answers in relation to diagnosed disorders and perception of pain. Appl Ergon. 1999;30(4):325–330. doi: 10.1016/S0003-6870(98)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolen AR, Henneberger PK, Liang X, Sama SR, Preusse PA, Rosiello RA, et al. The validation of work-related self-reported asthma exacerbation. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64(5):343–348. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.028662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Int Med. 2003;138:W1–W12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00012-w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer C, Mikkelsen S. The context of a study influences the reporting of symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2003;76(8):621–624. doi: 10.1007/s00420-003-0463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cegolon, et al. The primary care practitioner and the diagnosis of occupational diseases. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:405. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PY, Popovich PM (2002) Correlation: parametric and nonparametric measures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications