Abstract

Abstract

An intriguing feature of several nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) on neurons is that their subunits contain a highly conserved cysteine residue located near the intracellular mouth of the receptor pore. The work summarized in this review indicates that α3β4-containing and α4β2-containing neuronal nAChRs, and possibly other subtypes, are inactivated by elevations in intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). This review discusses a model for the molecular mechanisms that underlie this inactivation. In addition, we explore the implications of this mechanism in the context of complications that arise from diabetes. We review the evidence that diabetes elevates cytosolic ROS in sympathetic neurons and inactivates postsynaptic α3β4-containing nAChRs shortly after the onset of diabetes, leading to a depression of synaptic transmission in sympathetic ganglia, an impairment of sympathetic reflexes. These effects of ROS on nAChR function are due to the highly conserved Cys residues in the receptors: replacing the cysteine residues in α3 allow ganglionic transmission and sympathetic reflexes to function normally in diabetes. This example from diabetes suggests that other diseases involving oxidative stress, such as Parkinson's disease, could lead to the inactivation of nAChRs on neurons and disrupt cholinergic nicotinic signalling.

Dr Ellis Cooper is a professor of physiology at McGill University in Montreal. He received his PhD from McMaster University and did postdoctoral training at Harvard before taking a faculty position at McGill. Cooper has had a long-standing interest in the structure and function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Currently, Cooper's lab focuses on two main issues. One is activity-dependent mechanisms that govern the rearrangement and function of synapses as neural circuits become established during early postnatal life. The second focus of the Cooper lab is diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Cooper and colleagues are investigating diabetic-induced dysautonomias that result from a hyperglycemia-induced defect in ganglionic synaptic transmission. Dr. Arjun Krishnaswamy received his PhD from McGill University and is currently doing postdoctoral research at Harvard.

|

Introduction

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are neurotransmitter-gated ion channels present on skeletal muscle cells, many neurons, and a number of non-neuronal cells throughout the body, such as lymphocytes and epithelial cells. Muscle nAChRs have been studied extensively and a considerable amount of information is available about their structure–function relationships, pharmacological properties, and gating mechanisms (Corringer et al. 2000; Karlin, 2002; Unwin, 2005; Purohit et al. 2007; Auerbach, 2010). In contrast, much less is known about nAChRs on neurons, although, given the high homology at the amino acid level among nAChRs subunits expressed by muscle and those expressed by neurons, much of what is known about nAChRs on muscle appears to hold true for nAChRs on neurons (Dani & Bertrand, 2007; Albuquerque et al. 2009). For example, upon ACh binding, nAChRs on both muscle and neurons rapidly gate a non-selective cation channel, although there are variations among subtypes of nAChRs in their sensitivity to agonist and antagonists, the time course for desensitization and recovery from desensitization, calcium permeability, and single channel conductance (Dani & Bertrand, 2007; Albuquerque et al. 2009). Therefore, as a first approximation, it appears that nAChRs on muscle and those on neurons function similarly. On the other hand, there are two striking exceptions to the similarity between muscle and neuronal nAChRs: (1) unlike muscle nAChRs, nAChRs on neurons are inactivated by mild elevations in cytosolic reactive oxygen species (ROS); and (2) the receptor channel of neuronal nAChRs rectifies, that is it conducts ions when the membrane is hyperpolarized but not when it is depolarized. These two properties raise several questions: What is the underlying mechanism for the interaction between ROS and the receptor? What makes the channel of neuronal nAChRs rectify? Is there a link between inward rectification and the inactivation of the receptor by cytosolic ROS? Do these properties have important physiological roles? This review confines itself to some of these questions, and the relevance of these issues for cholinergic nicotinic signalling.

Mild elevation in ROS inactivates nAChRs on neurons

The initial observations that nAChRs on neurons are inactivated by cytosolic ROS come from studies on ACh-evoked currents on neonatal rodent sympathetic neurons grown in culture (Campanucci et al. 2008). Normally, when recording ACh-evoked currents from rodent sympathetic neurons that have been in culture for 1–2 weeks, ACh evokes large (3–6 nA) rapid inward currents that are extremely stable. However, the stability of the currents depends on the thiol/disulfide redox status of the cytoplasm. For example, elevating cytosolic ROS in these neurons by including highly reactive hydroxyl radicals from a Fenton reaction (Fe2++ H2O2→ Fe3++ OH•+ OH−) in the recording electrode causes the ACh-evoked currents to run down. This rundown is use dependent, and the amount of rundown depends on the number, and not the frequency, of ACh applications. After a series of ACh applications, the peak amplitude of the ACh-evoked currents is usually reduced to approximately 10–20% of the initial response and does not recover over the time course of a typical whole-cell recording (usually 1 h) (Campanucci et al. 2008). Moreover, use-dependent rundown of the ACh-evoked current is not due to cumulative desensitization because when the receptors are fully desensitized with long ACh applications, the currents recover almost completely; however, the currents still run down with the same number of repeated ACh applications as it takes with shorter, non-desensitizing pulses. An interesting feature of this ROS-induced rundown of the ACh-evoked currents is that elevations in ROS must be paired with receptor activation; elevating cytosolic ROS alone has little effect on the receptor, consistent with this use-dependent feature of the rundown (Campanucci et al. 2008). This long-lasting, use-dependent rundown of the ACh-evoked currents is referred to as receptor inactivation.

Initially, when rodent sympathetic neurons are in culture for only 1–2 days, the ACh-evoked currents also run down irreversibly with repeated ACh application. This receptor inactivation on these young neurons, however, can be prevented by increasing intracellular anti-oxidants, adding further support for the idea that the thiol/disulfide redox status of the cytoplasm is an important determinant of this long-lasting receptor inactivation (Campanucci et al. 2008).

A major source of ROS in cells comes from the mitochondria as a by-product of oxidative phosphorylation and the generation of ATP by the electron transport chain (ETC). Relevantly, blocking complex III of the ETC with antimycin A in autonomic neurons elevates ROS and also causes an irreversible, use-dependent rundown of the ACh-evoked currents. These observations are not restricted to nAChRs on peripheral neurons because elevations in mitochondrial ROS can also cause a long-lasting, use-dependent inactivation of recombinantly expressed α4β2 nAChRs (Campanucci et al. 2008), a receptor subtype expressed by many neurons in the CNS. An intriguing suggestion from these experiments is that highly active mitochondria may produce sufficient ROS to inactivate nAChRs, particularly in compartments such as nerve terminals and postsynaptic domains, which are rich in mitochondria, and also where most nAChRs are located on neurons.

Less invasive methods can also elevate cytosolic ROS and inactivate nAChRs. For example, a transient disruption of nerve growth factor (NGF) signalling elevates ROS in sympathetic neurons without an obvious detrimental effect on neuronal survival (Kirkland & Franklin, 2001; Kirkland et al. 2002; Campanucci et al. 2008). This increased ROS signalling, however, causes a use-dependent inactivation of the receptor and a rundown of the ACh-evoked currents. The effect of this transient disruption in NGF signalling on receptor inactivation is prevented by co-treating cultures with anti-oxidants at the time of NGF withdrawal; this confirms that the mild elevation in ROS inactivates nAChRs, and not some other component of the NGF receptor signalling cascade.

Taken together, the above results indicate that it is possible to inactivate nAChRs by elevating cytosolic ROS levels. The question is whether such a mechanism ever occurs in normal physiological and/or pathophysiological conditions. Relevantly, there are a number of diseases where oxidative stress is implicated in the underlying pathology (Smith et al. 1996; Dauer & Przedborski, 2003; Mattson, 2004; Abou-Sleiman et al. 2006; Lin & Beal, 2006; Savitt et al. 2006; Tomlinson & Gardiner, 2008; Bishop et al. 2010). If any of these diseases are manifested in neurons with nAChRs, we predict that cholinergic nicotinic signalling in these neurons would be significantly depressed. To give a good example, we discuss complications that arise as a result of diabetes.

Diabetes elevates ROS in sympathetic neurons and depresses synaptic transmission in sympathetic ganglia

Diabetes, a disease that results from insufficient insulin production or from insulin resistance, causes a chronic elevation of plasma glucose. This chronic elevation of circulating glucose is usually considered toxic to cells. In neurons, it is generally believed that the resultant increase in intracellular glucose during diabetes causes an increased production of NADH and FADH2 through glycolysis and the TCA cycle (Tomlinson & Gardiner, 2008). According to this model, the surplus of electron donors in the electron transport chain blocks the ETC at complex III, and causes an overproduction of superoxide (ROS), shifting the intracellular thiol/disulfide redox state towards more oxidative conditions, creating oxidative stress (Brownlee, 2005; Thomlinson & Gardiner, 2008). If this scenario occurs in sympathetic neurons, then chronic hyperglycaemia should elevate cytosolic ROS and inactivate nAChRs.

Hyperglycaemia inactivates nAChR on cultured sympathetic neurons

First, to determine whether hyperglycaemia elevates ROS in sympathetic neurons, ROS imaging experiments were conducted. These experiments revealed that within 1 week of exposing cultured sympathetic neurons to hyperglycaemic conditions, ROS-induced fluorescence was elevated 1.5- to 2-fold. Equally relevant, electrophysiological measurements on these neurons in hyperglycaemic conditions demonstrated that the ACh-evoked currents ran down. To show that elevated cytosolic ROS was responsible for receptor inactivation, anti-oxidants were included in the recording electrode when measuring the ACh-evoked currents. By recording from neurons in the same culture with or without antioxidants in the electrode, it was possible to demonstrate directly that anti-oxidants prevent the rundown of the ACh-evoked currents. These results indicate that hyperglycaemia elevates cytosolic ROS in sympathetic neurons and causes nAChRs to inactivate (Campanucci et al. 2010). If these results hold for nAChRs on sympathetic neurons in an in vivo setting, then chronic hyperglycaemia should inactivate postsynaptic nAChRs and depress synaptic transmission in intact ganglia.

Hyperglycaemia depresses fast synaptic transmission in sympathetic ganglia and induces dysautonomia

Briefly, the majority of people suffering from diabetes develop dysautonomia and/or autonomic neuropathy, a heterogeneous disorder encompassing a wide range of abnormalities and unique syndromes that adversely affect the quality of life and life expectancy (Dyck et al. 1993; Duby et al. 2004; Kelkar, 2005; Vinik & Zeigler, 2007). Moreover, in the prevertebral superior mesenteric and celiac ganglia of patients with diabetes, many sympathetic nerve endings are significantly enlarged and appear dystrophic, and these nerve terminal abnormalities increase with the duration and severity of diabetes (Schmidt et al. 1993; Schmidt, 1996).

Importantly, the nerve terminal abnormalities observed in prevertebral sympathetic ganglia are not present in paravertebral ganglia, including those involved in cardiovascular function (Schmidt, 1996; Schmidt et al. 2009). Therefore, the question remains, what causes cardiovascular dysautonomia in people with diabetes? The activity of autonomic nerves is controlled largely by the central nervous system (CNS) through excitatory cholinergic–nicotinic synapses in autonomic ganglia. These peripheral cholinergic–nicotinic synapses in autonomic ganglia represent the final output of various CNS structures that regulate autonomic activity. Given the effects of hyperglycaemia on nAChR function on sympathetic neurons in vitro, one possibility is that hyperglycaemia depresses synaptic transmission in autonomic ganglia, producing dysautonomia by disconnecting CNS control of peripherial tissues. If so, diabetic-induced dysautonomia might resemble the dysautonomia observed in people with autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathies (AAG), a rare autoimmune disease in which the body produces antibodies against ganglionic nAChRs (Vernino et al. 2008, 2009).

This idea was tested in mice after making them diabetic with streptozotocin (STZ), a drug that destroys pancreatic β-cells (Junod et al. 1969; Lenzen, 2008). In these diabetic mice, the nerve-evoked EPSPs in sympathetic ganglia were dramatically depressed within 1 week of diabetes, and the longer the disease progressed the greater the depression. Similar results were also obtained with Akita (Ins2Akita) mice, mice with a mutation in the insulin 2 gene (heterozygote males develop diabetes at 3 weeks of age). These results indicate that hyperglycaemia disrupts functional synapses in sympathetic ganglia. As a consequence of depressed synaptic transmission, activity in sympathetic nerves is reduced in diabetic mice, and reflexes that depend on sympathetic nerve activity, such as heart rate and cold-induced thermogenesis are depressed (Campanucci et al. 2010).

In STZ-treated mice and Akita mice, hyperglycaemia is produced by lower than normal levels of circulating insulin. Therefore, one might ask whether the effects on ganglionic transmission are due to a lack of insulin rather than hyperglycaemia. A good argument against this view comes from experiments on ob/ob and db/db mice. These mice have a disruption in leptin signalling and become obese and hyperglycaemic, even though insulin levels are elevated ∼10-fold; such mice are usually considered a model of type 2 diabetes (Coleman, 1978). The nerve-evoked EPSPs in the SCG of these mice are significantly depressed, demonstrating a strong correlation between hyperglycaemia-induced ROS and depressed ganglionic transmission in both type 1 and type 2 models of diabetes.

These observations are being extended to other autonomic ganglia in diabetic mice. In addition to the superior cervical ganglia, the effects of diabetes on synaptic transmission were investigated in the superior mesenteric ganglion, a prevertebral sympathetic ganglion, the adrenal medulla, and the parasympathetic submandibular ganglion. In both the superior mesenteric and the adrenal medulla, synaptic transmission was depressed by more than 50% within 1 week after the onset of diabetes. In contrast, synaptic transmission in parasympathetic ganglia was only depressed by approximately 10%, even after 3–4 months. These results indicate that the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system is more affected by diabetes than the parasympathetic branch (A. Rudechenko & E. Cooper, unpublished).

ROS-induced inactivation of nAChRs by postranslational modification

The inactivation of nAChRs induced by cytosolic ROS is essentially irreversible. It is as if the receptor becomes trapped in a long-lasting, non-conducting state. A clue to the mechanism that produces this inactivated state came initially from studies on ion conduction through the channel pore, and in particular, studies on mechanisms that cause the channel to rectify (Haghighi & Cooper, 1998, 2000).

Inward rectification

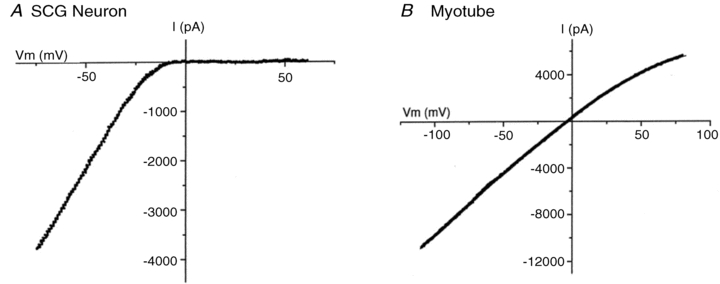

Briefly, for nAChRs on muscle, the channel conductance is essentially constant and independent of membrane potential. In contrast, nAChRs on neurons are strong inward rectifiers; that is, when the receptor is activated at negative potentials, such as the resting potential, the receptor conducts cations and depolarizes the membrane potential; however, when activated at positive potentials, it is as if the channel is blocked and the receptor does not conduct ions (Fig. 1) (Mathie et al. 1987, 1990; Ifune & Steinbach, 1990; Sands & Barish, 1991; Sands & Barish 1992; Haghighi & Cooper 1998, 2000). Physiologically, this rectification makes it easier for the nAChR-induced EPSPs to excite neurons because without rectification the action potential currents would flow through the receptors instead of across the membrane, as first shown over 60 years ago (Fatt & Katz, 1951).

Figure 1. Current–voltage relationship for ACh-evoked currents on a neonatal rat SCG neuron (left) and a neonatal rat myotube (right).

Adapted from Haghighi & Cooper (2000) with permission from the Society for Neuroscience.

Importantly, single channel currents from neuronal nAChRs in cell-free patches do not rectify; this indicates that inward rectification is not intrinsic to the receptor channel (Haghighi & Cooper 1998), and suggests that some intracellular molecule(s), acting as a gating particle, is responsible for blocking the channel at positive membrane potentials. Taking clues from work on inward rectifying K+ channels (Nichols & Lopatin, 1997; Lu, 2004), and calcium permeable glutamate receptors (Bowie & Mayer, 1995), the blocking molecules were identified as intracellular polyamines (Haghighi & Cooper 1998).

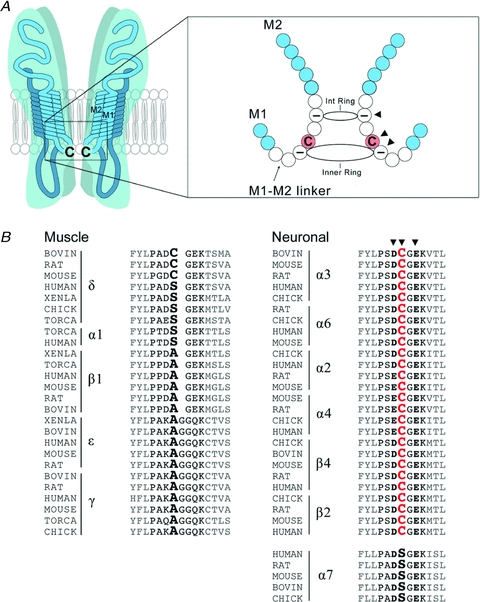

Structurally, polyamines interact with neuronal nAChRs at two closely spaced rings of negatively charged amino acids that are present in the short intracellular linker between transmembrane domains 1 and 2 near the inner mouth of the receptor channel (Fig. 2). Together these negatively charged rings attract the positively charged polyamines to the mouth of the channel. When the channel opens at depolarized potentials, polyamines attempt to move out through the channel, and occlude it. Evidence for this scheme comes from mutagenesis experiments which show that when the negative charges at the intermediate ring are removed, the channel no longer rectifies (Haghighi & Cooper, 2000).

Figure 2. Conserved cysteine residues in the M1–M2 linker of neuronal nAChRs.

A, schematic diagram of a single neuronal nAChR showing the conserved cysteine residues in the short cytoplasmic M1–M2 linker region at the intracellular mouth of the pore. On the right is an enlargement of the M1–M2 segment showing that the conserved Cys residues (arrowhead) are located between the two rings (intermediate (int) and inner) of negatively charged residues (arrowheads). B, amino acid sequence alignment of several neuronal and muscle nAChR subunits at the M1–M2 linker region for different vertebrate species. The critical Cys residues are highly conserved in many neuronal nAChR subunits but not in most muscle nAChR subunits. Arrowheads indicate the conserved Cys and the negatively charged amino acids that make up the intermediate and inner rings.

Cys residues in the M1–M2 linker

On several of the subunits that make up nAChRs on neurons, including α3, α4, α6, β2 and β4, there is a highly conserved cysteine residue situated between the two negatively changed rings (Fig. 2). Cysteine residues are vulnerable to oxidation, and can cross-link through disulfide bonds to other cysteines in close proximity. Therefore, if these Cys residues are targets of cytosolic ROS, then the subunits in a receptor may become cross-linked, thereby constraining subunit movement and preventing the channel from opening. Interestingly, polyamines are ROS scavengers and are attracted to this site by the negatively charged rings. Under normal physiological conditions, these polyamines possibly protect the Cys from oxidation. Relevantly, all muscle nAChR subunits lack Cys residues in the M1–M2 linker, except for delta, and muscle nAChRs are not inactivated by elevations in cytosolic ROS (Campanucci et al. 2008).

Nicotinic receptors on sympathetic neurons are composed of α3 and β4 (and possibly other) subunits, likely in a pentameric arrangement (Anand et al. 1991; Cooper et al. 1991). To test whether these Cys residues are involved in hyperglycaemia-induced inactivation of the receptor, one can change the Cys in α3 with mutagenesis and express it in cultured sympathetic neurons; however, it is best to conduct these experiments with sympathetic neurons from α3-null mice to avoid potential complications from the expression of endogenous α3.

α3-null mice

Briefly, sympathetic neurons from α3-null mice (α3 KO) lack functional nicotinic receptors and do not have ACh-evoked inward currents. Consequently, these mice have no synaptic transmission in sympathetic ganglia, and as a result develop severe dysautomonia (Xu et al. 1999; Rassadi et al. 2005; Krishnaswamy & Cooper, 2009). As inbred strains, these mice die within the first few days after birth; however, outbred strains live for months (Krishnaswamy & Cooper, 2009). Interestingly, although there is no synaptic transmission in sympathetic ganglia, preganglionic terminals establish the normal density of morphological synapses with sympathetic neurons, and these silent synapses persist for at least 4–6 weeks. When α3 is expressed in cultured α3 KO sympathetic neurons, the α3 subunits co-assemble with endogenous β (and possibly other) subunits into functional nAChRs and rescue the ACh-evoked inward currents; these rescued currents appear indistinguishable from those on WT sympathetic neurons. Equally relevant, one can rescue synaptic transmission in sympathetic ganglia of α3-null mice within 1–2 days after infecting mice with α3-expressing viral vectors (Krishnaswamy & Cooper, 2009). These rescue experiments open up a number of studies on activity-dependent processes involved in the development of neurocircuitry. Rescuing synaptic transmission with α3-expressing viral vectors also provides one with a powerful tool to investigate whether Cys residues in the M1–M2 linker are involved in hyperglycaemia-induced inactivation of the receptor.

Hyperglycaemia-induced ROS inactivates nAChRs through a cysteine residue in the M1–M2 linker

When cultured α3 KO neurons are infected with vectors to express the WT α3 subunit and are exposed to high glucose, the ACh-evoked currents run down with repeated ACh application, similar to those on WT neurons. Interestingly, however, when α3 KO neurons are infected with vectors expressing the mutant α3 subunit lacking the conserved Cys (α3C−A) and exposed to high glucose, the ACh-evoked currents are stable (Campanucci et al. 2010). Therefore, for hyperglycaemia-induced ROS to cause long-lasting inactivation of nAChRs, these Cys near the intracellular mouth of the channel are essential. These results predict that removing the Cys from α3 should prevent the hyperglycaemia-induced depression of synaptic transmission in sympathetic ganglia.

Indeed, experiments in which α3 KO mice were infected with adenoviral vectors expressing either WT α3 or α3C−A demonstrate that removing the Cys from α3 subunits protect synapses in autonomic ganglia from diabetic-induced depression. Furthermore, diabetic α3 KO mice infected with α3C−A have normal sympathetic reflexes, consistent with the idea that reduced sympathetic reflexes in diabetic mice result from a depression in synaptic transmission in sympathetic ganglia (Campanucci et al. 2010).

These results demonstrate that hyperglycaemia interferes with the function of α3-containing nAChRs through Cys residues on the α3 subunit. Since these Cys residues are conserved in human α3, β4 and β2 subunits, it is reasonable to conclude that human ganglionic α3-containing nAChRs would be similarly inactivated by hyperglycaemia-induced ROS. If this is the case, then it would suggest that some dysautonomia in people with diabetes may result from a disruption in ganglionic transmission.

Summary and significance

The work summarized in this review indicates that α3β4-containing and α4β2-containing neuronal nAChRs, and possibly other subtypes, are inactivated by elevations in intracellular ROS. Taken together, this work suggests the following model. The targets of ROS are the Cys residues in the M1–M2 linker, near the intracellular mouth of the channels. Normally these Cys are protected by polyamines, ROS scavengers that are attracted to this site by the rings of negatively charged amino acid on each subunit. However, mild elevations in cyosolic ROS out-compete the polyamines and oxidize these Cys residues. Once oxidized, the Cys cross-link receptor subunits and constrain movement within the receptor molecule, trapping the receptor in a non-conducting, inactivated state. However, this process requires receptor activation, suggesting that either the Cys need to move in close proximity with one another to cross-link, or that the Cys are hidden while the receptor is in the resting state and become exposed to ROS during the transition from closed to open. In addition, the Cys residues appear hidden from ROS when the receptor is in the desensitized state.

Good evidence for the involvement of the Cys residues in M1–M2 linker comes from mutating the Cys in α3 and showing that α3-containing receptors are no longer activated by elevations in ROS. However, further experiments are needed to establish whether this model provides a complete explanation for the rundown of the ACh-evoked currents on neurons. For example, it is necessary to show that ROS act directly on the channel and not through some intermediary molecule to inactivate the receptor. Second, it is important to demonstrate biochemically that receptor subunits covalently cross-link when the receptor is activated in the presence of elevated cytosolic ROS.

It is not clear whether these Cys residues near the mouth of the channel have other roles in receptor function. They do not appear to be important for receptor assembly or membrane targeting, nor do they have an obvious role in receptor desensitization or recovery from desensitization (Campanucci et al. 2010). One possibility is that these Cys residues act as a ‘brake’ to prevent excessive excitation through nAChR-induced depolarizations when neurons are under oxidative stress.

Once the receptors have been inactivated, they do not recover readily, at least not over the time course of whole-cell recording. One possibility is that intracellular reductants do not have access to this domain near the inner mouth of the channel, or that vital reductants are dialysed out of the cell during whole-cell recording. A second possibility is that once the Cys have been oxidized and cross-linked, the receptor must be internalized before the Cys can be reduced and the receptor recycled back to the membrane. A third possibility is that the receptors are irreversibly locked in the inactivated state, and replaced by newly synthesized receptors while the inactive receptors are degraded. Further experiments are required to decide among these scenarios.

Although the ring of Cys residues at the intracellular mouth of the channel is necessary for ROS-induced inactivation of neuronal nAChRs, it may not be sufficient: to form disulfide bonds, the α-carbons of Cys residues on the facing sides of two interfacing helices can only be, on average, 5–6 Å from each other. Without more structural information, therefore, it is difficult to predict, for example, whether ROS-induced inactivation can be conferred to muscle nAChRs by engineering the Cys ring in a homologous position to that in neuronal receptors.

Regardless of the exact molecular mechanisms that underlie inactivation and recovery of receptors, the loss of functional nAChRs is likely to have significant implications not only for complications from diabetes, but for a number of diseases where oxidative stress is involved. For example, oxidative stress is an important component of Parkinson's disease, a disease that results in a selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (Dauer & Przedborski, 2003; Abou-Sleiman et al. 2006; Lin & Beal, 2006). Many substantia nigra neurons express α4β2-containing and α6β2-containing nAChRs (Zoli et al. 2002; Champtiaux & Changeux, 2004); therefore during the early progression of Parkinson's disease, oxidative stress in dopaminergic nigral neurons may induce long-lasting inactivation of these α4β2-containing and α6β2-containing nAChRs, contributing, in part, to the movement disorders and cognitive deficits experienced by people with Parkinson's disease.

It is worth pointing out that noradrenergic neurons are at particularly high risk for oxidative stress because molecules involved in the synthesis of the catecholamines, such as tyrosine hydroxylase and monoamine oxidase, produce H2O2 as normal by-products of their activities (Coyle & Puttfarcken, 1993). In addition, catecholamines undergo auto-oxidation and produce H2O2, and accumulated H2O2 slowly decomposes to the highly reactive hydroxyl radical, a process that is accelerated markedly in the presence of Fe2+ by the Fenton reaction. Therefore, when subjected to an additional oxidative insult, sympathetic neurons may have difficulty keeping ROS in balance. For example, if ROS are elevated in sympathetic neurons of patients with diseases related to mitochondrial dysfunction and/or oxidative stress, ganglionic transmission will be depressed, and these patients will experience sympathetic insufficiencies, such as poorly regulated blood pressure, cardiac arrhythmias, and perturbations in other homeostatic control processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Linda Cooper for comments on the manuscript, and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation for support.

Author's present address

A. Krishnaswamy: Centre for Brain Science, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

References

- Abou-Sleiman PM, Muqit MK, Wood NW. Expanding insights of mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:207–219. doi: 10.1038/nrn1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand R, Conroy WG, Schoepfer R, Whiting P, Lindstrom J. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes have a pentameric quaternary structure. J Biol Chem. 1991;226:11192–11198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A. The gating isomerization of neuromuscular acetylcholine receptors. J Physiol. 2010;588:573–86. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.182774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop NA, Lu T, Yankner BA. Neural mechanisms of ageing and cognitive decline. Nature. 2010;464:529–535. doi: 10.1038/nature08983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie D, Mayer ML. Inward rectification of both AMPA and kainate subtype glutamate receptors generated by polyamine-mediated ion channel block. Neuron. 1995;15:453–462. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanucci V, Krishnaswamy A, Cooper E. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species inactivate neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and induce long-term depression of fast nicotinic synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1733–1744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5130-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanucci V, Krishnaswamy A, Cooper E. Diabetes depresses synaptic transmission in sympathetic ganglia by inactivating nAChRs through a conserved intracellular cysteine residue. Neuron. 2010;66:827–834. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Changeux J-P. Knockout and knockin mice to investigate the role of nicotinic receptors in the central nervous system. Prog Brain Res. 2004;145:235–251. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(03)45016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman DL. Obese and diabetes: two mutant genes causing diabetes-obesity syndromes in mice. Diabetologia. 1978;14:141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00429772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper E, Couturier S, Ballivet M. Pentameric structure and subunit stoichiometry of a neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature. 1991;350:235–238. doi: 10.1038/350235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corringer PJ, Le Novère N, Changeux JP. Nicotinic receptors at the amino acid level. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:431–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Puttfarcken P. Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 1993;262:689–695. doi: 10.1126/science.7901908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:699–729. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duby JJ, Campbell RK, Setter SM, White JR, Rasmussen KA. Diabetic neuropathy: An intensive review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:160–173. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck PJ, Kratz KM, Karnes JL, Litchy WJ, Klein R, Pach JM, Wilson DM, O'Brien PC, Melton LJ, 3rd, Service FJ. The prevalence by staged severity of various types of diabetic neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy in a population-based cohort: the Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study. Neurology. 1993;43:817–824. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatt P, Katz BJ. An analysis of the end-plate potential recorded with an intracellular electrode. Physiol. 1951;115:320–370. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1951.sp004675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi AP, Cooper E. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are blocked by intracellular spermine in a voltage-dependent manner. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4050–4062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-11-04050.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi AP, Cooper E. A molecular link between inward rectification and calcium permeability of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine α3β4 and α4β2 receptors. J Neurosci. 2000;20:529–541. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00529.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ifune CK, Steinbach JH. Rectification of acetylcholine-elicited currents in PC12 pheochromocytoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4794–4798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junod A, Lambert AE, Stauffacher W, Renold AE. Diabetogenic action of streptozotocin: relationship of dose to metabolic response. J Clin Invest. 1969;48:2129–2139. doi: 10.1172/JCI106180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin A. Emerging structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrn731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelkar P. Diabetic neuropathy. Semin Neurol. 2005;25:168–173. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland RA, Franklin JL. Evidence for redox regulation of cytochrome c release during programmed neuronal death: antioxidant effects of protein synthesis and caspase inhibition. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1949–1963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01949.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland RA, Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF, Franklin JL. A Bax-induced pro-oxidant state is critical for cytochrome c release during programmed neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6480–6490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06480.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaswamy A, Cooper E. An activity-dependent retrograde signal induces the expression of the high-affinity choline transporter in cholinergic neurons. Neuron. 2009;61:272–286. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen S. The mechanisms of alloxan- and streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:216–226. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z. Mechanism of rectification in inward-rectifier K+ channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:103–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.150822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathie A, Colquhoun D, Cull-Candy SG. Rectification of currents activated by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat sympathetic ganglion neurones. J Physiol. 1990;427:625–655. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathie A, Cull-Candy SG, Colquhoun D. Single-channel and whole-cell currents evoked by acetylcholine in dissociated sympathetic neurons of the rat. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1987;232:239–248. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1987.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2004;430:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Lopatin AN. Inward rectifier potassium channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:171–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit P, Mitra A, Auerbach A. A stepwise mechanism for acetylcholine receptor channel gating. Nature. 2007;446:930–933. doi: 10.1038/nature05721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassadi S, Krishnaswamy A, Pié B, McConnell R, Jacob MH, Cooper E. A null mutation for the α3 nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptor gene abolishes fast synaptic activity in sympathetic ganglia and reveals that ACh output from developing preganglionic terminals is regulated in an activity-dependent retrograde manner. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8555–8566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1983-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands SB, Barish ME. Calcium permeability of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channels in PC12 cells. Brain Res. 1991;560:38–42. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91211-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands SB, Barish ME. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor currents in phaeochromocytoma (PC12) cells: dual mechanisms of rectification. J Physiol. 1992;447:467–487. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitt JM, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease: molecules to medicine. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1744–1754. doi: 10.1172/JCI29178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RE, Green KG, Snipes LL, Feng D. Neuritic dystrophy and neuronopathy in Akita (Ins2(Akita)) diabetic mouse sympathetic ganglia. Exp Neurol. 2009;216:207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RE, Plurad SB, Parvin CA, Roth KA. The effect of diabetes and aging on human sympathetic autonomic ganglia. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:143–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RE. The neuropathology of human sympathetic autonomic ganglia. Microscop Res Tech. 1996;35:107–121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19961001)35:2<107::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Perry G, Richey PL, Sayre LM, Anderson VE, Beal MF, Kowall N. Oxidative damage in Alzheimer's. Nature. 1996;382:120–121. doi: 10.1038/382120b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson DR, Gardiner NJ. Glucose neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:36–45. doi: 10.1038/nrn2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N. Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:967–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernino S, Hopkins S, Wang Z. Autonomic ganglia, acetylcholine receptor antibodies, and autoimmune ganglionopathy. Auton Neurosci. 2009;146:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernino S, Sandroni P, Singer W, Low PA. Autonomic ganglia: target and novel therapeutic tool. Neurology. 2008;70:1926–1932. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312280.44805.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinik AI, Zeigler D. Diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. Circulation. 2007;115:387–397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.634949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M, Moretti M, Zanardi A, McIntosh MJ, Clementi F, Gotti C. Identification of the nicotinic receptor subtypes expressed on dopaminergic terminals in the rat striatum. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8785–8789. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08785.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Gelber S, Orr-Urtreger A, Armstrong D, Lewis RA, Ou CN, Patrick J, Role L, De Biasi M, Beaudet AL. Megacystis, mydriasis, and ion channel defect in mice lacking the α3 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5746–5751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]