Abstract

C-MOPP is a chemotherapy regimen for the treatment of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Because rituximab improves results in B-cell NHL, we added rituximab to C-MOPP, giving it the term C-MOPP-R. We retrospectively report the results of C-MOPP-R treatment for follicular lymphoma at Saint Louis University Cancer Center from 2000-2009. Treatment response was assessed with fusion PET/CT using International Harmonization Project Criteria and toxicity using National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0. Thirty-seven patients with follicular lymphoma were treated at our institution with C-MOPP-R. The complete response rate was ninety-four percent and sixty-eight percent in untreated and relapsed patients, respectively. The median progression-free and overall survivals were not reached with median observation time of 34 months. Development of peripheral neuropathy required truncation of planned vincristine dosing in nearly half of patients. We believe that C-MOPP-R results in excellent response rates, progression-free, and overall survival for untreated and relapsed follicular lymphoma and capped vincristine dosing is essential to optimize safety.

Keywords: Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin, Positron Emission Tomography, antibodies, monoclonal, antineoplastic agents

Introduction

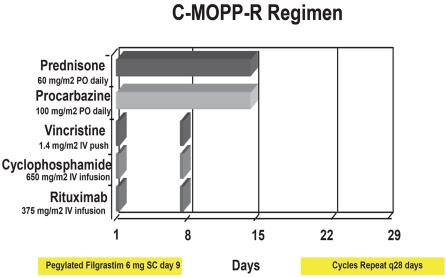

Morgenfeld et al. were the first to report a combination chemotherapy regimen of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and procarba-zine (COPP) in 1975 [1]. Longo et al. reported a median time to relapse of 7.1 years in the 79% of patients with nodular mixed lymphoma who achieved a complete remission with a similar regimen, C-MOPP [2]. Although chemotherapy regimens of similar composition with various modifications of dose and schedule demonstrated mixed results subsequently [3-5], we remained impressed by the durability of complete remissions afforded by C-MOPP for patients with follicular lymphoma. We have been using this chemotherapy backbone since 2000 for both newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma patients. Because rituximab demonstrated early promising results as both a single agent [6,7] and combined with chemotherapy [8], we incorporated it into the C-MOPP regimen, giving it the term C-MOPP-R [9] (Figure 1). We report the results of thirty-seven patients with untreated and relapsed follicular lymphoma treated at Saint Louis University from 2000-2009 with C-MOPP-R.

Figure 1.

Schema of the C-MOPP-R chemotherapy program.

Materials & methods

Study design

The study was a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of patient charts at Saint Louis University Cancer Center. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this analysis.

Setting

Records of all lymphoma diagnoses were obtained from our clinic database from 2000 through 2009. Only records with a diagnosis of follicular lymphoma were further considered. Charts of follicular lymphoma cases were screened; the present analysis is restricted to cases receiving C-MOPP-R immunochemotherapy. Follow-up information was obtained from medical charts.

Participants

We defined follicular lymphoma according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification [10] as a follicle centre cell B cell lymphoma but required a follicular component present in specimens. Excision biopsy of lymphatic tissue was required and in all cases this was a lymph node. Grade was defined according to the WHO 2008 definition. All patients in this analysis had preserved renal and hepatic function prior to therapy, defined as GFR >60cc/min by Cockroft-Gault equation, bilirubin <3 mg/dL and prothrombin time <15 seconds. All patients had adequate baseline hematologic function, with absolute neutrophil count >1500 cells/mcL and platelet count >100,000 cells/mcL. No patients had > grade 1 neuropathy at baseline. Cardiac and pulmonary functions were not assessed routinely unless concern was suggested at the initial visit.

Variables

We report response rates to C-MOPP-R according to International Workshop (IW) criteria [11-13] as a primary objective. Responses were divided into complete (CR), partial (PR), and overall (OR=complete plus partial). Stable or progressive disease is reported in separate categories. We report toxicity of the regimen according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria (NCICTC) for Adverse Events, version 3.

Data sources/measurement

Staging

All patients with de novo disease underwent appropriate staging workup including history and physical, complete blood count, chemistry, bone marrow biopsy, and radiological assessment. Complete records of relapsed patients were obtained from referral centers; however, initial workup was frequently incomplete usually due to lack of lactate dehydro-genase level. Patients with relapsed disease were each formally restaged as for de novo patients. Original biopsy material was reviewed by hematopathologists in all cases, and repeat biopsy of involved tissue at relapse was performed in all but one case. Overall, twenty-seven patients were staged with fusion FDG PET/CT; nine patients were staged with separate PET and CT scans of chest, abdomen, and pelvis; one patient was staged with CT scan alone prior to availability of PET at our institution. Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index was calculated in all de novo patients but was not possible to calculate for relapsed patients due to incomplete information.

Therapy

All patients received C-MOPP-R immunochemotherapy (Figure 1). Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor was routinely administered. Pegylated filgrastim is currently given day nine. Overlap between procarbazine and pegylated filgrastim has been described in a prior report [14]. The vincristine dose was uncapped, but the agent was discontinued at the development of ≥ grade II peripheral neuropathy. Prophylactic antiemetics were routine. All patients received prophylaxis for Pneumocystis, bacterial, fungal, and viral infections throughout chemotherapy. The prophylactic regimen includes: acyclovir (200mg po bid) or valacyclovir (500mg po bid), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole one double strength tablet oral M, W, F, levofloxacin 500mg oral daily, and fluconazole 100mg oral daily. If patients were allergic to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, atovaquone 1500mg or dapsone 100mg oral daily were substituted. Pneumocystis and viral prophylaxis were continued until the postchemotherapy absolute CD4 count was ≥ 200 cells/mcL. Most patients were enrolled on our single institution phase II clinical trial at the completion of C-MOPP-R, in which patients receive planned consolidation therapy. See discussion section for more details.

Response Assessment

Response was determined according to IW criteria incorporating clinical examination, bone marrow aspirate/ biopsy, and radiologic assessment. Twenty-four patients underwent fusion PET/CT and had their complete set of images reviewed both on the day of study and retrospectively by a board certified nuclear medicine physician. Responses were retrospectively categorized according to the Revised Response Criteria for Lymphoma [12], with utilization of the Imaging Subcommittee standards regarding PET interpretation [13].

Due to a change in computer software at our institution in June 2004, the PET scans performed prior to this date could not be viewed as a full set of images. In ten cases, a paper copy of the images was available in the patient's chart, and based on the hard copy, the nuclear medicine physician categorized the response as above. In the remaining four cases, neither computer nor hardcopy images could be obtained; response was determined from the initial radiological assessment. For one patient with CT scans only and two patients with non-FDG avid adenopathy, we determined response by the 1999 Response Criteria for Lymphoma [11]. Imaging was performed in all cases at the conclusion of therapy unless an interim scan demonstrated complete remission and clinical follow up raised no suspicion for disease progression. All patients with negative interim scans had at least two more cycles of C-MOPP-R therapy beyond imaging assessment. Cases with initial bone marrow involvement underwent repeat bone marrow biopsy after at least three cycles of chemotherapy to assess remission.

Bias

The nuclear medicine physician was not involved in the clinical care of any patients in this study and is free of bias. No financial relationships exist between any physicians involved in this study and any of the products used as part of this study.

Study size

We identified fifty-nine patients with follicular lymphoma treated from 2000-2009. Thirty-seven of the fifty-nine patients received C-MOPP -R and are included in the analysis. The primary reason for patients not receiving C-MOPP-R was that the patient was already in remission and referred for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or other consolidation. For patients with ECOG performance status >2 or above the age of 80, we chose alternative regimens. All thirty-seven patients are assessable for response and toxicity; twenty-five upfront and twelve relapsed.

Quantitative variables and statistical methods

Response and toxicity rates were quantified. Progression free survival was calculated from the date of treatment initiation to evidence of relapsed disease, death due to any cause, or last follow-up visit. Overall survival was calculated from the date of treatment initiation to death from any cause or last follow-up visit.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1, both de novo and relapsed. The percentage of de novo patients with Ann Arbor stage III/IV disease was nearly ninety percent, and the distribution of FLIPI scores in this cohort was similar to the population on which the score was derived [15].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| De Novo | Relapsed | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 25 | 12 |

| Age, median | 52 | 54 |

| Age, range | 28-73 | 36-67 |

| B Symptoms | 21% | 33% |

| Grade | ||

| 1 | 40% | 25% |

| 2 | 28% | 33% |

| 3 | 32% | 42% |

| Stage | ||

| 1 | 8% | 0 |

| 2 | 8% | 17% |

| 3 | 21% | 33% |

| 4 | 63% | 50% |

| FLIPI | ||

| 0-1 | 42% | N/A |

| 2 | 29% | N/A |

| 3-5 | 29% | N/A |

| No. Prior Chemotherapy Regimens | N/A | 1- 10 (84%) |

| 2- 1 (8%) | ||

| 3- 0 | ||

| 4- 1 (8%) | ||

Efficacy

One patient underwent response assessment with CT alone, nine patients underwent separate PET and CT scans, and twenty-seven patients underwent fusion PET/CT. In twenty-three cases, the full set of images was reviewed centrally by our nuclear medicine physician. In ten cases, only partial images were reviewed centrally, and in four cases images could not be obtained, and response was assessed by chart review of initial radiologic assessment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Response assessment

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment Tool | ||

| CT alone | N=1 | 3% |

| PET | N=9 | 24% |

| Fusion PET/CT | N=27 | 73% |

| Assessment Method | ||

| Full Scans Reviewed Centrally | N=23 | 62% |

| Images Reviewed Centrally | N=10 | 27% |

| Reports Reviewed | N=4 | 11% |

In the upfront setting, twenty-three of twenty-five or ninety-four percent of patients achieved a confirmed CR. Two of twenty-five patients achieved a PR, for an OR rate of one hundred percent (Table 3). For patients with relapsed disease, the confirmed CR rate was sixty-eight percent, with eight percent of patients obtaining a PR for an overall response rate of seventy-six percent. One patient had stable disease and two progressive disease, respectively. For the entire cohort, a CR rate of eighty-four percent, a PR rate of eight percent, and an OR rate of ninety-two percent were achieved. Both patients with progressive disease had a response during therapy but follow-up imaging revealed progression within two months.

Table 3.

Response rates

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| De Novo | N=25 | |

| Complete | N= 23 | 94 % |

| Partial | N= 2 | 6 % |

| Stable Disease | N= 0 | 0 |

| Progression | N= 0 | 0 |

| Relapsed | N=12 | |

| Complete | N= 8 | 67% |

| Partial | N= 1 | 8 % |

| Stable Disease | N= 1 | 8 % |

| Progression | N= 2 | 17% |

For eleven patients who were not enrolled in the clinical trial and received no consolidation therapy after C-MOPP-R, follow-up exists through 7/1/11 (Table 4). One patient in relapse after CHOP therapy developed progressive disease 1.5 months after the second cycle of C-MOPP-R and ultimately died of lymphoma. One patient died of complications of congestive heart failure with no evidence of lymphoma. One patient relapsed with a disease-free interval of 38 months, underwent an autologous bone marrow transplant after salvage chemotherapy, and is currently alive and free of disease, 67 months after initial C-MOPP-R chemotherapy. Eight patients are in first continuous complete remission of various durations.

Table 4.

Patients treated with C-MOPP-R alone

| Patient | Age | U/R | Stage | Grade | FLIPI | # Cycles | Response | Response Duration, months | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 56 | R | NR | 2 | NR | 2 | PD | N/A | Died of Lymphoma |

| 2 | 48 | U | 2A | 3A | 0 | 6 | CR | 21 | Alive NED |

| 3 | 69 | U | 3B | 2 | 5 | 6 | CR | 21 | Alive NED |

| 4 | 60 | U | 3A | 3 | 3 | 6 | CR | 26 | Alive NED |

| 5 | 28 | U | 1A | 3 | 0 | 6 | CR | 31 | Alive NED |

| 6 | 73 | U | 4A | 2 | 4 | 5 | CR | 45 | Died Unrelated |

| 7 | 48 | U | 3A | 1 | 2 | 6 | CR | 52 | Relapsed, Alive NEDs/p autoBMT |

| 8 | 51 | U | 4B | 1 | 1 | 6 | CR | 60 | Alive NED |

| 9 | 49 | U | 4A | 1 | 1 | 6 | CR | 81 | Alive NED |

| 10 | 58 | U | 4A | 1 | 2 | 6 | CR | 94 | Alive NED |

| 11 | 51 | U | 3A | 2 | 3 | 6 | CR | 104 | Alive NED |

U=untreated; R=relapsed; NED=No evidence of disease; PD= progressive disease; PR=partial response; CR=complete response; NR=not recorded

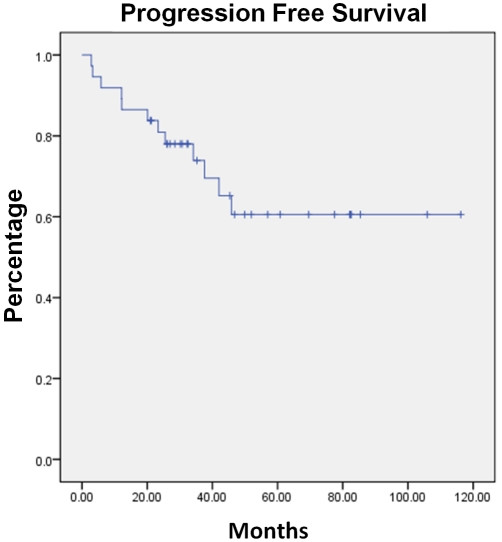

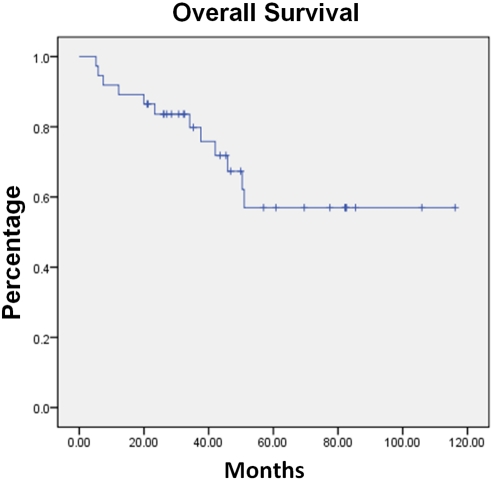

With a median observation time from initiation of C-MOPP-R to data analysis of 34 months (range 3-116 months), the progression-free and overall survival have not been reached. The median progression-free survival at three years is 75% and overall survival 80%, respectively. (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Progression-Free Survival of the entire cohort treated with C-MOPP-R.

Figure 3.

Overall Survival of the entire cohort treated with C-MOPP-R.

Toxicity

See Table 5 for rates of grade III/IV adverse events according to NCICTC in de novo and relapsed patients. Because this was not a prospective study, rates of grade I/II adverse events could not be calculated as these were not routinely recorded in the patient's chart. However, vincristine was stopped routinely at ≥ grade II neurotoxicity. Fifteen of twenty-five de novo patients required omission of vincristine for neuropathy, one after cycle one, two after cycle two, one after cycle three, three after cycle four, and two after cycle five. Two of twelve patients with relapsed disease required omission of vincristine from the regimen after cycle two due to neuropathy. No patients developed grade III or IV peripheral neuropathy in spite of using an uncapped dose of vincristine.

Table 5.

NCI grade 3/4 toxicity rates

| De Novo | Relapsed | |

|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | ||

| Neutropenia | 21% | 17% |

| Anemia | 6% | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 8% |

| Non-Hematologic | ||

| Peripheral Neuropathy | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 6% | 8% |

| Thrombosis | 11% | 0 |

| Nausea | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 |

One patient with de novo disease developed a grade IV ischemic cerebrovascular event and two de novo patients developed a grade IV pulmonary embolism, both after the second cycle. One of the patients who developed pulmonary embolism developed a non-neutropenic gram negative sepsis and died of septic complications. The precise role of the chemotherapy in the causation of the above events is unclear, but there is a temporal association between chemotherapy and complications.

Neutropenia was the hematologic toxicity seen most often in spite of growth factor use. Two patients in the de novo setting required dose reduction or dose omission of cyclophosphamide due to neutropenia. In total, four de novo patients and three relapsed patients had C-MOPP-R truncated at the discretion of the treating physician. The four de novo patients had received five cycles, and the relapsed patients four cycles prior to termination. All of the patients whose chemotherapy was truncated had interim PET or CT studies demonstrating complete remission at least two cycles prior to termination, and it was felt by the treating physicians that further chemotherapy would result in further toxicity for the patient with possible compromise in stem cell collection and ability to receive consolidation therapy.

Discussion

Aggressive immunochemotherapy may alter the natural history of follicular lymphoma [16-19], and the majority of evidence suggests that achievement of a complete response is associated with superior disease-free survival [20-23]. We believe the goal of initial therapy in young patients without substantial comorbidity should be complete response. The complete and overall response rates reported previously for up-front treatment of follicular lymphoma with immunochemotherapy are listed in Table 6 [20-23], and those studies in relapsed disease in Table 7 [24-26].

Table 6.

Response rates and duration upfront follicular lymphoma

| Regimen | Patients | Overall response rate | Complete response rate | Median response duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-CVP | 159 | 81% | 41% | 66 months |

| R-CHOP | 222 | 97% | 20% | Not reached at 3 years |

| R-CHVP-I | 175 | 81% | 67% | Not reached at 3 years |

| R-MCP | 105 | 92% | 50% | Not reached at 4 years |

Table 7.

Response rates and duration relapsed follicular lymphoma

| Regimen | Patients | Overall response Rate | Complete response rate | Median response duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCR | 54 | 91% | 74% | Not reached at 45 months |

| R-FCM | 66 | 79% | 33% | Estimated 16 months |

| R-BM | 29 | 92% | 50% | Estimated 17 months |

The high response rates in this retrospective analysis versus other published regimens may be due to a number of factors. First, we assessed the response in most of our patients using fusion PET/CT scans with International Harmonization Project criteria. Most prior reports have assessed complete remission by the original IW criteria for response, in which computed tomography is used as the imaging tool for assessment. A few reports exist which compare end of therapy assessment between CT and PET in follicular lymphoma [27-29]. Most patients in complete remission by CT scan in these reports are also reported to be in complete remission by PET (or PET/CT) imaging, with utilization of various criteria for positive versus negative PET. The percentage of patients with unconfirmed CR or PR by CT criteria who have CR by PET criteria is relatively high, ranging from 52-84% amongst the three reports [27-29]. This indicates that many patients in partial remission by CT criteria are in complete remission by PET criteria, and becomes important when comparing complete remission results across studies. Indeed, our complete remission rate may in part be higher than many past reports as a result of assessment method.

Second, the regimen is different from the other immunochemotherapy regimens in several ways. Rituximab is administered for twelve doses rather than six doses, which may enhance the efficacy of this immunochemotherapy, although we are unaware of any data comparing twelve versus six doses of rituximab in this context. In addition, vincristine is utilized more aggressively than other regimens, both in dose (uncapped at 1.4mg/m2 versus capped 1.2mg/m2) and frequency (12 doses in 24 weeks versus 6 doses in 18 weeks). We are unaware of any reports detailing the optimal dose and schedule of this agent both in terms of efficacy and toxicity. Cumulative exposure to cyclophosphamide is higher in C-MOPP than most regimens, which may be partly responsible for high response rates, as it is one of the most efficacious single agents in NHL [30]. Finally, procarbazine, which has demonstrated single agent utility in follicular lymphoma in untreated [31,32] and relapsed patients [33], is administered with this regimen. Along with more rituximab and cyclophosphamide than other regimens, it may have contributed to the grade III/IV hematological toxicity seen in spite of G-CSF use. Gastrointestinal toxicity was very manageable with antiemetics, and there are no cases of secondary neoplasia. Although procarbazine has demonstrated idiosyncratic pneumonitis [34] and hepatotoxicity [35], it does not have cumulative, dose-limiting organ toxicity.

The median progression-free and overall survival compare favorably to other studies of frontline therapy in follicular lymphoma. It is recognized that the majority of our patient cohort received consolidation therapy, but we did include patients with relapsed disease, who have a less favorable prognosis. Some of the patients treated with C-MOPP-R induction were part of our phase II pilot study utilizing a combination of immuno-chemotherapy, radioimmunotherapy, and autologous transplant, which began accrual in 2006 and will require at least five more years for data to mature. In the study, patients are given six cycles of C-MOPP-R followed by one standard dose of Zevalin upon count recovery, which is then followed by a BEAM-conditioned autologous transplant [36].

We found that all but two of our patients had FDG-avid disease on the staging PET scans, which is consistent with prior reports [27,29]. Although SUVs were not systematically analyzed, the intensity of uptake was similar to many of our patients with Hodgkin and Diffuse Large B cell Lymphoma. All of the patients who achieved a partial response to therapy had reduction in FDG avidity of all but one site, and although the one site must be considered positive by the International Harmonization Project criteria, the intensity of uptake was dramatically reduced in all cases. It would be interesting to know how these isolated, less FDG-avid areas would behave clinically over time. If our subsequent management would have been altered by knowing whether these areas represented residual disease, biopsy would have been pursued. The primary toxicity our patients experienced during C-MOPP-R chemotherapy was peripheral neuropathy, and nearly one-half of patients required omission of vincristine during therapy. Using a capped dose of vincristine may have allowed more cycles to be administered and may have lessened grade I/II peripheral neuropathy rates. We have begun using capped vincristine dosing at our institution, although the effect this will have on efficacy at present is unknown.

No infectious etiology could be determined in the two cases of pneumonitis, and symptoms returned to baseline with administration of corticosteroids. Both patients continued to receive cyclophosphamide and procarbazine, which are associated with pulmonary toxicity in prior reports [37, 38], without recurrent pulmonary symptoms. The lack of completion of six cycles of chemotherapy in seven patients was due to physician discretion of perceived relative benefit and harms of further chemotherapy versus consolidation therapy. We do not believe that the response rates would be altered as a result of this, as all of these patients were in complete remission at the time therapy was truncated. Consistent with the experience of Longo et al [2], prolonged progression-free survival with C-MOPP-R alone was seen in this cohort, with three cases exhibiting progression-free survivals of 81, 94, and 104 months, respectively. Importantly, prolonged remission is not restricted to C -MOPP-R, as R-CHOP has shown durable remissions [39]. However, cumulative cardiotoxicity with anthracycline is a concern, and procarba-zine is not associated with cumulative organ toxicity, which is important in follicular lymphoma given the long natural history of this disease.

Conclusion

In summary, we report excellent complete response rates, progression-free survival, and overall survival with an immunochemotherapy regimen, C-MOPP-R, in patients with both up-front and relapsed follicular lymphoma. We suggest utilization of capped vincristine dosing with this regimen to attenuate grade I/II peripheral neurotoxicity. Consideration of this regimen for patients with follicular lymphoma is reasonable based on these data. Ultimately, further comparative data of various regimens in randomized trials will inform clinical practice in the up-front and relapsed treatment of this disease.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Julie Nguyen for assistance with figure and table optimization.

References

- 1.Morgenfeld MC, Pavlovsky A, Suarez A, Somoza N, Pavlovsky S, Palau M, Barros CA. Combined cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (COPP) therapy of malignant lymphoma. Cancer. 1975;36:1241–1249. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197510)36:4<1241::aid-cncr2820360409>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longo DL, Young RC, Hubbard SM, Wesley M, Fisher RI, Jaffe E, Berard C, DeVita VT., Jr Prolonged initial remission in patients with nodular mixed lymphoma. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:651–656. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-5-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezdinli EZ, Costello WG, Silverstein MN, Berard C, Hartsock RJ, Sokal JE. Moderate versus intensive chemotherapy of prognostically favorable non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer. 1980;46:29–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800701)46:1<29::aid-cncr2820460105>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glick JH, Barnes JM, Ezdinli EZ, Berard CW, Orlow EL, Bennett JM. Nodular mixed lymphoma: results of a randomized trial failing to confirm prolonged disease-free survival with COPP chemotherapy. Blood. 1981;58:920–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang R, Todd D, Chan TK, Chiu E, Lie A, Ho F. COPP chemotherapy for elderly patients with intermediate and high grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 1993;11:43–50. doi: 10.1002/hon.2900110106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin P, Grillo-López AJ, Link BK, Levy R, Czuczman MS, Williams ME, Heyman MR, Bence-Bruckler I, White CA, Cabanillas F, Jain V, Ho AD, Lister J, Wey K, Shen D, Dallaire BK. Rituximab Chimeric Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibody Therapy for Relapsed Indolent Lymphoma: Half of Patients Respond to a Four-Dose Treatment Program. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2825. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hainsworth JD, Burris HA, 3rd, Morrissey LH, Litchy S, Scullin DC, Jr, Bearden JD, 3rd, Richards P, Greco FA. Rituximab monoclonal antibody as initial systemic therapy for patients with low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2000;95:3052–3056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czuczman MS, Grillo-López AJ, White CA, Saleh M, Gordon L, LoBuglio AF, Jonas C, Klippenstein D, Dallaire B, Varns C. Treatment of Patients with Low-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma with Combination of Chimeric Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibody and CHOP Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:268–276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fesler MJ, Osman M, Glauber J, Petruska PJ. C-MOPP: Results of a Forgotten Regimen for Follicular Lymphoma in the Era of Rituximab and PET [abstract] Blood. 2009;114:4755a. Abstract 4755. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al., editors. IARC: Lyon; 2008. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, Lister TA, Vose J, Grillo-López A, Hagenbeek A, Cabanillas F, Klippensten D, Hiddemann W, Castellino R, Harris NL, Armitage JO, Carter W, Hoppe R, Canellos GP. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Fisher RI, Hagenbeek A, Zucca E, Rosen ST, Stroobants S, Lister TA, Hoppe RT, Dreyling M, Tobinai K, Vose JM, Connors JM, Federico M, Diehl V. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juweid ME, Stroobants S, Hoekstra OS, Mottaghy FM, Dietlein M, Guermazi A, Wiseman GA, Kostakoglu L, Scheidhauer K, Buck A, Naumann R, Spaepen K, Hicks RJ, Weber WA, Reske SN, Schwaiger M, Schwartz LH, Zijlstra JM, Siegel BA, Cheson BD. Use of positron emission tomography for response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the Imaging Subcommittee of International Harmonization Project in Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:571–578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engert A, Bredenfeld H, Döhner H, Ho AD, Schmitz N, Berger D, Bacon P, Skacel T, Easton V, Diehl V. Pegfilgrastim support for full delivery of BEACOPP-14 chemotherapy for patients with high-risk Hodgkin's lymphoma: results of a phase II study. Haematologica. 2006;91:546–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, White J, Armitage JO, Arranz-Saez R, Au WY, Bellei M, Brice P, Caballero D, Coiffier B, Conde-Garcia E, Doyen C, Federico M, Fisher RI, Garcia-Conde JF, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, Haïoun C, LeBlanc M, Lister AT, Lopez-Guillermo A, McLaughlin P, Milpied N, Morel P, Mounier N, Proctor SJ, Rohatiner A, Smith P, Soubeyran P, Tilly H, Vitolo U, Zinzani PL, Zucca E, Montserrat E. Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index. Blood. 2004;104:1258–1265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swenson WT, Wooldridge JE, Lynch CF, Forman-Hoffman VL, Chrischilles E, Link BK. Improved survival of follicular lymphoma patients in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5019–5026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher RI, LeBlanc M, Press OW, Maloney DG, Unger JM, Miller TP. New treatment options have changed the survival of patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8447–8452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Q, Fayad L, Cabanillas F, Hagemeister FB, Ayers GD, Hess M, Romaguera J, Rodriguez MA, Tsimberidou AM, Verstovsek S, Younes A, Pro B, Lee MS, Ayala A, McLaughlin P. Improvement of overall and failure-free survival in stage IV follicular lymphoma: 25 years of treatment experience at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1582–1599. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sacchi S, Pozzi S, Marcheselli L, Bari A, Luminari S, Angrilli F, Merli F, Vallisa D, Baldini L, Brugiatelli M. Introduction of rituximab in frontline and salvage therapies has improved outcome of advanced-stage follicular lymphoma patients. Cancer. 2007;109:2077–2082. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herold M, Haas A, Srock S, Neser S, Al-Ali KH, Neubauer A, Dölken G, Naumann R, Knauf W, Freund M, Rohrberg R, Höffken K, Franke A, Ittel T, Kettner E, Haak U, Mey U, Klinkenstein C, Assmann M, von Grünhagen U. Rituximab added to First-Line Mitoxantrone, Chlorambucil, and Prednisolone Chemotherapy Followed by Interferon Maintenance Prolongs Survival in Patients with Advanced Follicular Lymphoma: An East German Study Group Hematology and Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(15):1986–1992. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, Schmitz N, Lengfelder E, Schmits R, Reiser M, Metzner B, Harder H, Hegewisch-Becker S, Fischer T, Kropff M, Reis HE, Freund M, Wörmann B, Fuchs R, Planker M, Schimke J, Eimermacher H, Trümper L, Aldaoud A, Parwaresch R, Unterhalt M. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone(CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2005;106:3725–3732. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salles G, Mounier N, de Guibert S, Morschhauser F, Doyen C, Rossi JF, Haioun C, Brice P, Mahé B, Bouabdallah R, Audhuy B, Ferme C, Dartigeas C, Feugier P, Sebban C, Xerri L, Foussard C. Rituximab combined with chemotherapy and interferon in follicular lymphoma patients : results of the GELA-GOELAMS FL2000 study. Blood. 2008;112:4824–4831. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-153189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcus R, Imrie K, Solal-Celigny P, Catalano JV, Dmoszynska A, et al. Phase III Study of R-CVP Compared with Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, and Prednisone Alone in Patients with Previously Untreated Advanced Follicular Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4579–4586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forstpointner R, Dreyling M, Repp R, Hermann S, Hänel A, Metzner B, Pott C, Hartmann F, Rothmann F, Rohrberg R, Böck HP, Wandt H, Unterhalt M, Hiddemann W. The addition of rituximab to a combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone (FCM) significantly increases the response rate and prolongs survival as compared with FCM alone in patients with relapsed and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2004;104:3064–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sacchi S, Pozzi S, Marcheselli R, Federico M, Tucci A, Merli F, Orsucci L, Liberati M, Vallisa D, Brugiatelli M. Rituximab in Combination With Fludarabine and Cyclophosphamide in the Treatment of Patients With Recurrent Follicular Lymphoma. Cancer. 2007;110:121–128. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weide R, Hess G, Köppler H, Heymanns J, Thomalla J, Aldaoud A, Losem C, Schmitz S, Haak U, Huber C, Unterhalt M, Hiddemann W, Dreyling M. High anti-lymphoma activity of ben-damustine/mitoxantrone/rituximab in rituximab pretreated relapsed or refractory indolent lymphomas and mantle cell lymphomas. A multicenter phase II study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1299–1306. doi: 10.1080/10428190701361828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zinzani PL, Musuraca G, Alinari L, et al. Predictive role of positron emission tomography in the outcome of patients with follicular lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2007;7:291–295. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2007.n.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zinzani PL, Musuraca G, Alinari L, Fanti S, Tani M, Stefoni V, Marchi E, Fina M, Pellegrini C, Castellucci P, Farsad M, Baccarani M. Predictive value and diagnostic accuracy of F-18-fluoro-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography treated grade 1 and 2 follicular lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1548–1555. doi: 10.1080/10428190701422059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janikova A, Bolcak K, Pavlik T, Mayer J, Kral Z. Value of [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography in the Management of Follicular Lymphoma:The End of a Dilemma? Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2008;8:287–93. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2008.n.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones SE, Rosenberg SA, Kaplan HS, Kadin ME, Dorfman RF. Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. II. Single agent chemotherapy. Cancer. 1972;30:31–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197207)30:1<31::aid-cncr2820300106>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livingston RB, Carter SK. New York: IFI/Plenum Data Corp; 1970. Single agents in cancer chemotherapy; pp. 318–336. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunner KW, Young CW. A Methylhydrazine Derivative in Hodgkin's Disease and Other Malignant Neoplasms: Therapeutic and Toxic Effects Studied in 51 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1965;63:69–86. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-63-1-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaar BT, Salem P, Petruska PJ. Procarbazine for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:637–40. doi: 10.1080/10428190600591517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahmood T, Mudad R. Pulmonary toxicity secondary to procarbazine. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:187–188. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200204000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fesler MJ, Becker-Koepke S, Di Bisceglie A, Petruska P. Procarbazine-induced hepatotoxicity: case report and review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:540. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petruska PJ, Chaar BT, Fesler MJ. A Pilot Phase II Study of Sequential Treatment With Chemotherapy, Radioimmunotherapy and Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients With Follicular Lymphoma. Clinical-Trials.gov [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2006- [cited 2010 May 28]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01130194 NLM Identifier: NCT01130194. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spector JI, Zimbler H, Ross JS. Cyclophophamide pneumonitis. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:251. doi: 10.1056/nejm198207223070414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks BJ, Jr, Hendler NB, Alvarez S, Ancalmo N, Grinton SF. Delayed life-threatening pneumonitis secondary to procarbazine. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13:244–6. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199006000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Czuczman MS, Weaver R, Alkuzweny B, Berlfein J, Grillo-Lopez AJ. Prolonged Clinical and Molecular Remission in Patients with Low-Grade or Follicular non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treated with Rituximab plus CHOP chemotherapy: 9-year Follow-Up. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4711–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]