Abstract

The treatment of multiple myeloma has undergone important changes in the last few years. The use of novel agents, such as the immunomodulatory drugs thalidomide and lenalidomide, and the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, has increased the treatment options available and significantly improved the outcome of this rare disease. Several trials have shown the advantages linked to the use of novel agents both in young patients, who are considered eligible for transplantation, and elderly patients, who are considered transplant ineligible. In the non-transplant setting, novel agent-containing regimens have replaced the traditional melphalan-prednisone approach. Preliminary data also support the role of consolidation and maintenance therapy to further improve outcomes. An appropriate management of side effects is fundamental for the success of the treatment, and outcome should always be balanced against the toxicity profile associated with the regimen used. This review provides an overview of the latest strategies including novel agents used to treat elderly patients with multiple myeloma.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, elderly patients, new drugs, thalidomide, lenalidomide, bortezomib

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common hematologic malignancy. It accounts for 1% of all cancers and 13% of hematologic neoplasms. The median age at diagnosis is 70 years, with 37% of patients younger than 65 years, 26% aged 65 to 74 years, and 37% older than 75 years [1-3].

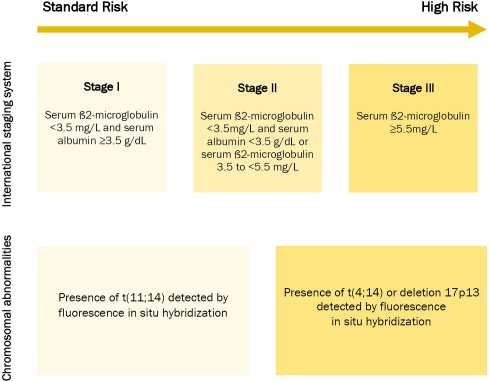

The diagnosis of MM is based on the presence of at least 10% clonal bone marrow plasma cells and serum and/or urinary monoclonal protein [4, 5]. The disease is classified as symptomatic or asymptomatic. Symptomatic MM is characterized by evidence of end-organ damage caused by plasma cell proliferation, and it is defined by the presence of the CRAB features, namely hypercalcemia, renal failure, anaemia, and bone disease. Recognizing organ damage is essential in order to identify symptomatic MM [4, 5]. Treatment should be started immediately for patients with symptomatic disease; while asymptomatic MM only requires clinical observation, since early treatment has shown no benefit [6, 7]. Patients are stratified into three risk groups according to the International Staging System (ISS). Risk groups are based on serum ß2-microglobulin and albumin levels at diagnosis [8]. High risk diseases and poor prognosis are defined with the presence of high levels of serum ß2-microglobulin (stage III). Cytoge-netic abnormalities, detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) are, in some cases, associated with worse outcome and a more aggressive approach is required. The presence of deletion 17p13, translocation t(4;14) t(14;16) or chromosome 1 abnormalities are associated with poor prognosis (Figure 1) [9, 10].

Figure 1.

Patient risk-stratification and prognosis

Patient characteristics have a significant role in the treatment planning: patients younger than 65 years, without severe comorbidities, who are able to undergo intensive treatment, are considered eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). Patients older than 65 years or with serious comorbidities are usually not considered ASCT candidates and need a gentler approach. As the biological age may differ from the chronological age, it is necessary to consider comorbidities when determining eligibility of patients for ASCT [11].

For more than 40 years, melphalan-prednisone (MP) was considered the standard treatment in the transplant-ineligible setting. A meta-analysis of 27 randomized trials compared different chemotherapy combinations with MP. Chemotherapy induced higher responses (60.0% vs 53.2%, P<0.0001) but similar median OS (generally no more than 3 years), and MP was better tolerated [12].

The introduction of novel agents, such as the immunomodulatory drugs (IMIDs) thalidomide and lenalidomide, and the first in-class protea-some inhibitor bortezomib led to great advances in the treatment of this rare disease [13]. The major goal of treatment is to prolong both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). However, newer and more efficacious therapies enabled to achieve a complete response (CR) in a larger proportion of patients. In the transplant setting, CR was found to be closely related to OS [14]. With the availability of novel agents, a greater number of elderly patients are now able to obtain a CR. A recent analysis on 1,175 elderly patients showed a significant association between the achievement of CR and long-term outcome, thus supporting the use of novel agents to achieve maximal response also in patients over 75 years [15].

This paper will provide an update of MM treatment in the elderly population, based on the results of the most recent trials and meta-analyses.

Thalidomide-based regimens

The combination of thalidomide with high dose dexamethasone (TD) showed higher efficacy compared to the old standard MP, but toxicity and treatment discontinuation were higher with dexamethasone. The rate of non-disease-related mortality in the TD group was twice as high as in the MP group, and infections were the main cause. This was even more evident in patients older than 72 years with poor performance status [16]. Prompt and appropriate management of the main adverse events (Table 1), the choice of different steroids (eg. prednisone vs dexamethasone) and treatment schedules tailored on patients characteristics (Table 2) may be crucial for the success of the treatment itself, enabling patients to stay on treatment longer and to benefit more from it.

Table 1.

Management of adverse events in multiple myeloma patients treated with novel agents

| Toxicity | Novel agent suspected to cause the event | How to manage the event | Dose-adjustment recommended |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutropenia | Lenalidomide, Bortezomib | G-CSF until neutrophil recovery in case of uncomplicated grade 4 AE or grade 2-3 AEs complicated by fever or infection. | 25% to 50% drug reduction |

| Thrombocytopenia | Bortezomib, Lenalidomide | Plate let transfusion in case of occurrence of grade 4 AE. | 25% to 50% drug reduction |

| Anaemia | Bortezomib, Lenalidomide | Erythropoietin or darbepoietin if hemoglobin level is ≤ 10 g/dL. | 25% to 50% drug reduction |

| Infection | All | Trimetoprin-cotrimoxazoie for Pneumocystis carinii prophylaxis during high-dose dexamethasone. Acyclovir or valacyclovir for HVZ prophylaxis during bortezomib-containing therapy. | 25% to 50% drug reduction |

| Neurotoxicity | Bortezomib, Thalidomide | Neurological assessment before and during treatment. Prompt dose reduction is recommended | Bortezomib: 25%-50% reduction for grade 1 with pain or grade 2 peripheral neuropathy; dose interruption until peripheral neuropathy resolves to grade 1 or better with restart at 50% dose reduction for grade 2 with pain or grade 3 peripheral neuropathy; treatment discontinuation for grade 4 peripheral neuropathy. Thalidomide: 50% reduction for grade 2 neuropathy; discontinuation for grade 3; resume Thalidomide at a decreased dose if neuropathy improves to grade 1. |

| Skin toxicity | Thalidomide, Lenalidomide | Steroids and antihistamines. | Interruption in case of grade 3-4 AE. 50% reduction in case of grade 2 AE. |

| Gastrointestinal toxicity | All | Appropriate diet, laxatives, physical exercise, hydration, antidiarrheics. | Interruption in case of grade 3-4 AEs 50% reduction in case of grade 2 AEs. |

| Thrombosis | Thalidomide, Lenalidomide | Aspirin 100-325 mg if no or one individual/myeloma thrombotic risk factor is present. LMWH orfull dose warfarin if there are two or more individual/myeloma risk factors and in all patients with thalidomide-related risk factors. | Drug temporary interruption and full anticoagulation, then resume treatment |

| Renal toxicity | Lenalidomide | Correct precipitant factors (dehydration, hypercalcemia, hyperuricemia, urinary infections, and concomitant use of nephrotoxic drugs). | Reduce dose according to creatinine clearance: If 30-60 mL/min: 10 mg/day; If < 30 mL/min without dialysis needing: 15 mg every other day; If < 30 mL/min with dialysis required: 5 mg/day after dialysis on dialysis day. |

| Bone pain | None | Start with simple non-opioid analgesics. If no improvement is detected continue with weak opioid analgesics. In case of no relief, use synthetic opioids or strong (natural) opioids. Local radiotherapy is also an effective strategy. | ––––– |

| Bone disease | None | Vetebropalsty (percutaneous injection of poiymethacryiate or equivalent material into the vertebral body). Use of balloon kyphoplasty enhances vertebral height. Long-term bisphosphonates may prevent bone disease. Further strategies are intravenous pamidronate, intravenous zoledronic acid as well as oral clodronate. | ––––– |

Table 2.

Recommended dose reductions according to age

| Drug | 65-75 years | > 75 years | Further reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone | 40 mg/d d 1,8,15,22 every 4 wks | 20 mg/d d 1,8,15,22 every 4 wks | 10 mg/d d 1,8,15,22 every 4 wks |

| Melphalan | 0.25 mg/kg or 9 mg/m2 d 1-4 every 4-6 wks | 0.18 mg/kg or 7.5 mg/m2 d 1-4 every 4-6 wks | 0.13 mg/kg or 5 mg/m2 d 1-4 every 4-6 wks |

| Thalidomide | 100 mg/d | 50 mg/d | 50 mg qod |

| Lenalidomide (plus dexamethasone) | 25 mg/d d 1-21 every 4 wks | 15 mg/d d 1-21 every 4 wks | 10 mg/d d 1-21 every 4 wks |

| Lenalidomide (plus melphalan-prednisone) | 10 mg/d d 1-21 every 4 wks | 5 mg/d d 1-21 every 4 wks | 5 mg qod d 1-21 every 4 wks |

| Bortezomib | 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly d 1,4,8,11 every 3 wks | 1.3 mg/m2 once weekly d 1,8,15,22 every 5 wks | 1.0 mg/m2 once weekly d 1,8,15,22 every 5 wks |

| Prednisone | 60 mg/m2 d 1-4 | 30 mg/m2 d 1-4 | 15 mg/m2 d 1-4 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 100 mg/d d1-21 every 4 wks | 50 mg/d d 1-21 every 4 wks | 50 mg qod d 1-21 every 4 wks |

d, day; wk, week; qod, every other day

The combination of melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide (MPT) was compared to MP in six randomized phase 3 studies [17-22]. The two Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome (IFM) studies showed that both PFS and OS were higher in the MPT arm [17, 18]. The Italian trial observed a PFS advantage that did not translate into a survival advantage for patients treated with thalidomide [22]. The Dutch/Belgian study detected differences in PFS/OS and event free survival (EFS) between the two treatment arms [21]. The Nordic trial did not find significant difference in terms of PFS and OS, although response were significantly better during the first year of treatment with MPT [20].

Finally, the Turkish trial detected considerably higher responses in MPT patients, as well as an initial not significant survival advantage in the MPT arm during the first six months of treatment [19]. In all these studies, grade 3-4 neutropenia was the main adverse event associated with MPT (16-48%), mostly related to melphalan. Peripheral neuropathy (6-23%) and venous thromboembolism (3-12%) were the main adverse events associated with thalidomide. Concomitant anti-thrombotic prophylaxis with aspirin, warfarin, or low molecular weight heparin is suggested [23].

Data from the MPT trials mentioned above were pooled together in a meta-analysis of 1,685 patients [24]. Median survival was 32.7 months with MP vs 39.3 months with MPT. This difference was more pronounced at 3 and 4 years, with early deaths in the MPT arm during the first year of therapy. This may suggest a lack of advantage of MPT over MP during the first year of therapy. Two-years PFS was 28.4% in MP and 42.5% in MPT. Responses were higher in the MPT arm, in particular very good partial response (VGPR) which was 9% with MP vs 25% with MPT. In this meta-analysis, correlation between OS/PFS and risk factors such as ISS, Durie/Salmon stages, performance status (WHO -PS), haemoglobin and/or creatinine values and others were difficult to demonstrate, because of the heterogeneity of patient baseline characteristics in each study. In particular, the meta-analysis failed to demonstrate that patients with poor performance status or with renal failure should not be treated with MPT. The sample size of patients with WHO-PS >2 or with high creatinine level was limited to draw definitive conclusions. Despite the limits of this meta-analysis, such as the heterogeneity of patient characteristics and the different treatment schedules, MPT improved OS and PFS in previously untreated MM patients, extending the median OS time by 20%. No advantage with MPT was found in patients with poor PS or renal impairment.

Based on these results, MPT is now considered a standard of care for elderly patients with MM.

Morgan et al. compared MP with a new thalidomide-based regimen, substituting melphalan with cyclophosphamide and prednisone with dexamethasone (CTD) in newly diagnosed elderly MM patients [25]. The overall response rate (ORR) was significantly higher in CTD than in MP group (63.8% vs 32.6% respectively, P<0.0001). After a median follow-up of 44 months, no difference in terms of PFS (median 12.4 months in the MP group vs 13 months in the CTD group) and OS (median 30.6 months with MP vs 33.2 months with CTD) was evidenced. Of note, patients with a good cytogenetic profile at FISH benefited from CTD and had improved OS, especially after the first 18 months of treatment. OS benefit was observed in all patients who reached CR, independently from the treatment received.

The most frequent (≥ 10%) adverse events occurred in the CTD arm were constipation (41%), infection (32%), sensory neuropathy (24%), and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (16%), Thromboprophylaxis was not mandatory initially. It was then introduced for patients in the CTD group, and thromboembolic events decreased dramatically. Considering the results achieved, CTD is a valid alternative for selected elderly newly diagnosed MM patients, with more benefits in those with good genetic profile. Prompt reduction of drug doses in case of adverse events is suggested to enable patients to stay on treatment for a longer time and benefit from it.

Based on the studies described above, the association of thalidomide with steroids and alkylant agents is a good option for elderly MM patients. In particular MPT has been approved by the European agency for drug administration (EMA) as therapy for new diagnosed MM not eligible to ASCT and is now considered the new standard of care in this setting.

Lenalidomide-based regimens

Recently, a phase 3 trial compared lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone (RD) vs lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone (Rd), in both young and elderly patients with new diagnosed MM (Table 3) [26]. Toxicity rates were significantly higher with RD, in particular DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE) (26% vs 12%), and infections (16% vs 9%). Considering its good toxicity profile, almost all recent trials are adopting the reduced-dose of dexamethasone (namely 40 mg once weekly or equivalent) and the use of high-dose dexamethasone is no longer recommended in newly diagnosed MM, especially in elderly patients. High dose dexamethasone is indicated in particular settings, when hypercalcemia, spinal cord compression, renal failure and pain occur at diagnosis.

Table 3.

Novel-agent containing induction regimens for elderly patients with multiple myeloma

| Combination | No. of patients | Schedule | ≥PR | CR | PFS/EFS/TTP | OS | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thalidomide-based | TD | 145 | T: 200 mg/day D: 40 mg, days 1-4 and 15-18 on even cycles and days 1-4 on odd cycles, during a 28-day cycle | 68% | 2% | 41% at 16 mo | 61% at 41 mo | [18] |

| MPT | 125 | M: 0.25 mg/kgdayl-4 P: 2 mg/kgdayl-4 T: 400 mg/day for twelve 6-week cycles | 76% | 13% | 50% at 28 mo | 50% at 52 mo | [17] | |

| MPT | 113 | M: 0.25 mg/kg day 1-4 P: 2 mg/kgdayl-4 T: 100 mg/day for twelve 6-week cycles | 62% | 7% | 50% at 24 mo | 50% at 44 mo | [18] | |

| MPT | 60 | M: 9 mg/m2 days 1-4 P: 60 mg/m2 days 1-4 T: 100 mg/day for 8 6-week cycles, followed by T: 100 mg/day until relapse | 58% | 9% | 50% at 21 mo* | 50% at 26 mo | [19] | |

| MPT | 182 | M: 0.25mg/kgdays 1-4 P: lOOmg/day days 1-4 For 6-week cycles until plateau T: 400mg/day until plateau, reduced to 200mg/day until progression | 57% | 13% | 50% at 15 mo | 50% at 29 mo | [20] | |

| MPT | 165 | M: 0.25 mg/kg P: 1 mg/kg days 1-5 T: 200 mg/day for 8 4-week cycles, followed by T: 50 mg/day until relapse | 66% | 23%# | 67% at 24 mo | 29% at 24 mo | [21] | |

| MPT | 167 | M: 4mg/m2 days 1-7 P: 40mg/m2 days 1-7 for six 4-week cycles T: lOOmg/day until relapse | 76% | 15% | 50% at 22 mo | 50% at 45 mo | [22] | |

| CTD | 426 | C: 500 mg/week T: 50 mgfor 4 weeks and increased every 4 weeks in 50 mgto a maximum of 200 mg/day D: 20 mg/day days 1-4 and 15-18 of each 28-cycle | 64% | 13% | 50% at 13 mo | 50% at 33 mo | [25] | |

| Lenalidomide-based | RD§ | 223 | R: 25 mg/day on day 1-21 D: 40 mg on day 1-4, 9-12, and 17-20 of a 28-day cycle | 81% | 17% | 63% at 24 mo | 75% at 24 mo | [26] |

| Rd§ | 111 | R: 25 mg/day on day 1-21 d: 40 mgon days 1, 8, 15 and 22 of a 28-day cycle | 70% | 14% | 65% at 24 mo | 87% at 24 mo | [26] | |

| MPR | 54 | M: 0.18-0.25 mg/kgdays 1-4 P: 2 mg/kgdays 1-4 R: 5-10 mgdays 1-21 for nine 4-week cycles | 81% | 24% | 92% at 12 mo | 100% at 12 mo | [27] | |

| MPR-R | 152 | M: 0.18 mg/kgdays 1-4 P: 2 mg/kgdays 1-4 R:10 mgdays 1-21 for nine 4-week cycles Maintenance R: 10 mg/day until relapse | 77% | 16% | 50% at 31 mo | 92% at 12 mo | [28] | |

| CRD | 53 | C: 300 mg/m2 days 1,8,15 R: 25 mg/day days 1-21 D: 40 mg days 1,8,15,22 (weekly continuously) | 79% | 2% | 50% at 28 mo | 87% at 24 mo | [29] | |

| Bortezomib-based | VMP | 344 | M: 9 mg/m2 days 1-4 P: 60 mg/m2 days 1-4 V: 1.3 mg/m2 days 1,4,8,11,22,25,29,32 for first four 6-week cycles; days 1,8,15, 22 for subsequent five 6-week cycles | 71% | 30% | 50% at 22 mo | 41% at 36 mo | [31, 32] |

| VMP | 257 | M: 9 mg/m2 day 1-4 P: 60 mg/m2 day 1-4 V: 1.3 mg/m2 day 1, 8, 15, 22 | 81% | 24% | 41% at 36 mo | 87% at 36 mo | [35] | |

| VMP | 130 | M: 9 mg/m2 day 1-4 P: 60 mg/m2 day 1-4 V: 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly (day 1,4,8,11,22,25,29, and 32) for one 6-week cycle, followed by once weekly (day 1, 8, 15, and 22) for five 5-week cycles Maintenance: V:1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8, 11, every 3 months T: 50 mg/day Or V: 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8, 11, every 3 months P: 50 mg every other day | 89% | 20% | 50% at 34 mo | 74% at 36 mo | [34] | |

| VTP | 130 | T: 100 mg/day P: 60 mg/m2 day 1-4 V: 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly (day 1, 4, 8, 11, 22, 25, 29 and 32) for one 6-week cycle, followed by once weekly (day 1, 8, 15 and 22) for five 5-week cycles Maintenance: V:1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8, 11, every 3 months T: 50 mg/day Or V: 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8, 11, every 3 months P: 50 mg every other day | 81% | 28% | 50% at 25 mo | 65% at 36 mo | [34] | |

| VMPT-VT | 254 | M: 9 mg/m2 day 1-4 P: 60 mg/m2 day 1-4 V: 1.3 mg/m2 day 1, 8, 15, 22 T: 50 mg day 1-42 for nine 5-week cycles Maintenance V: 1.3 mg/m2 every 15 days T: 50 mg/day | 89% | 38% | 56% at 36 mo | 89% at 36 mo | [35] | |

PR, partial response; CR, complete response; PFS, progression-free survival; EFS, event-free survival; TTP, time to progression; OS, overall survival; TD, thalidomide-dexamethasone; MPT, melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide; CTD: cyclophosphamide-thalidomide-dexamethasone; RD: lenalidomide plus high dose dexamethasone; Rd: lenalidomide plus low dose dexamethasone; MPR, melphalan-prednisone-lenalidomide; CRD: cyclophosphamide-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; MPR-R: MPR followed by lenalidomide maintenance; VMP, bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone; VTP, bortezomib-thalidomide-prednisone;; VMPT-VT, bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide followed by bortezomib-thalidomide maintenance; NA, not available; mo, months.

The study included both young and elderly patients

Disease-free survival

CR plus VGPR

The addition of lenalidomide to standard MP (MPR) led to impressive results [27]. A phase 1-2 dose-escalating open-label study evaluated the role of MPR in 50 new diagnosed MM patients, not eligible for ASCT. Treatment consisted of nine 28-day cycles of MPR combination, followed by maintenance therapy with lenalidomide alone. Aspirin was given as thromboprophylaxis.

The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was defined as 0.18 mg/kg melphalan and 10 mg/day lenalidomide. With these doses, 81% of patients achieved at least a partial response (PR), 47.6% achieved a VGPR and 23.8% achieved a CR. In all patients, 1-year EFS was 92% and OS was 100%. At the MTD, grade 3 adverse events included neutropenia (38.1%), thrombocytopenia (14.2%), febrile neutropenia (9.5%), vasculitis (9.5%) and thromboembolism (4.8%). Grade 4 adverse events were neutropenia (14.2%) and thrombocytopenia (9.5%). At the maximum tolerated dose, grade 3-4 adverse events were primarily hematologic, while non-hematologic adverse events were less than 10%, especially DVT, thanks to the use of aspirin. Peripheral neuropathy was never observed. A phase 3 study is comparing MPR vs MPR followed by lenalidomide maintenance (MPR-R) vs MP is underway [28]. Preliminary data showed that MPR-R reduced the risk of disease progression by 58% compared with MP. A landmark analysis proved the benefit of maintenance with lenalidomide: the risk of progression in the MPR-R arm was reduced by 69% compared to MPR. Grade 3-4 hematologic toxicities were more common with MPR-R than with MP (neutropenia 71% vs 30%, thrombocytopenia 38% vs 14%). Lenalidomide maintenance was well tolerated, and few serious adverse events were reported. It is worth mentioning that antithrombotic prophylaxis is highly recommended in patients receiving lenalidomide or thalidomide as induction therapies [23]. Based on these studies, MPR combination should be considered another valid alternative option for newly diagnosed MM elderly patients.

The use of another alkylant agent, like cyclophosphamide, in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (CRD) led to promising results [29]. In a phase 2 trial, 53 patients previously untreated received at least 4 cycles of CRD combination. Both patients eligible and those not eligible for ASCT were included. The median age of patients was 64 years (range 37-82 years). Forty-seven patients received at least 4 cycles of CRD therapy. At least PR was detected in 79% of patients, including at least VGPR rate of 30%. The most common grade 3-4 hematologic toxicity was neutropenia, that could be managed by reducing cyclophosphamide dose. Fatigue was the more frequent non-hematologic toxicity. The incidence of DVT was about 15%, and thromboprophylaxis was not mandatory, but suggested only in high-risk patients. After a median follow-up of 37 months, the median OS for the entire group of patients was not reached, with an estimated OS rate of 87% at 2 years. The 2-year PFS was 57% for the entire group.

In high-risk patients, according to mSMART criteria, the ORR was 93% (79% in those with standard risk) and the 2-yars PFS was 57% (61% in those with standard risk). OS was similar in the two group. A longer follow-up is needed to draw definitive conclusions.

A multicentre phase 3 trial comparing Rd vs MPR vs CRD in elderly MM patients is ongoing. One of the objectives of the study is to establish if the addition of an alkylant to Rd combination improves response/outcome and which alkylating agent is more effective in combination with Rd. The results so far obtained support the use of MPR as a valid option for MM elderly patients.

Bortezomib-based regimens

The association of bortezomib and dexamethasone (VD) showed to be an effective and safe frontline approach both in patients eligible and ineligible for ASCT [30].

Forty-nine patients have been enrolled and received bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, 11 for a maximum of six 3-week cycles. Patients who did not reach PR after 2 cycles or CR after 4 cycles received 40 mg of oral dexamethasone the day of and the day after bortezomib administration. Transplantation was not protocol-specified.

At least PR rate was 90%, with at least VGPR rate of 42%, and 19% patients in CR/ near CR.

After a median follow-up of 49 months, in patients who did not receive ASCT, median PFS was 21 months and the median OS was not reached. Toxicity was moderate with few cases of grade 3-4 of neutropenia and peripheral neuropathy. This trial confirmed the efficacy of VD combination also in patients who did not received high dose therapy. Few adverse events were detected and no DVT cases were seen, although patients did not receive any thromboprophylaxis.

The combination bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone (VMP) proved to be a valid alternative option for elderly patients. The phase 3 Velcade as Initial Standard Therapy (VISTA) study compared standard MP to VMP and found that responses, particularly CR, time to progression (TTP) and survival were significantly higher with VMP compared to MP [31, 32]. Hematologic toxicities were similar in the two groups. Grade 3-4 peripheral sensory neuropathy and neuralgia were more frequent with VMP, so were grade 3-4 gastrointestinal events (19% vs 5%). Of note, a sub-group analysis of the VISTA trial, showed the importance to achieve CR, also in the elderly population [33] Patients who reached CR, independently from the arm of randomization (MP or VMP), had a longer TTP, time to next therapy (TNT), and treatment free interval (TFI) compared with those who reached VGPR or PR. However, this analysis failed to show an OS advantage for CR. A possible explanation is the use of novel agent-containing combinations at relapse, that prolonged survival in patients who reached CR, VGPR or PR at the diagnosis. In the light of the impressive results achieved, VMP has become a valid alternative for newly diagnosed elderly patients.

Two phase 3 trials evaluated alternative combinations. The Spanish Myeloma Group (PETHEMA/GEM) compared VMP regimen to the combination bortezomib-thalidomide-prednisone (VTP) as induction therapy, and weekly bortezomib was used for both arms [34]. Patients were then randomized to receive maintenance therapy with bortezomib-thalidomide (VT) or bortezomib-prednisone (VP) for 3 years. A major goal was to evaluate which one between thalidomide or prednisone was the best drug to use in combination with bortezomib. Another important objective was to optimize treatment by reducing toxicity (eg. by using the weekly infusion of bortezomib). Response rates were similar in the two arms, so were also the 2-year TTP and OS. Nevertheless, VMP was better tolerated than VTP. Grade 3-4 cardiac toxicity was 8.5% vs 0 (P=0.001), thromboembolic events were 2% vs 1% (P=0.5) and peripheral neuropathy was 9% vs 5% (P=0.6) with VTP and VMP, respectively. Patients in the VMP arm had a higher rate of neutropenia (39% vs 22%, P=0.008), thrombocytopenia (27% vs 12%, P=0.0001) and infections (7% vs 1%, P=0.01). Discontinuation rate (17% vs 12%, P=0.03) and serious adverse events (31% vs 15%, P=0.01) were higher in the VTP arm. Maintenance therapy led to a substantial increase in CR rate, with no considerable difference between VT or VP. This approach led to a longer TTP compared to the VISTA trial (35 moths vs 24 months, respectively). No grade 3-4 hematologic toxicities were recorded during maintenance and less than 10% of grade 3 peripheral neuropathy (more frequent in the VT arm) were reported. These data confirm the role of VMP and suggest that, considering its toxicity profile, VMP should be preferred to VTP. The weekly-schedule of bortezomib reduced peripheral neuropathy and gastrointestinal toxicity without affecting efficacy.

A more complex approach including both thalidomide and bortezomib in combination with MP followed by maintenance with bortezomib-thalidomide (VMPT-VT) has been compared to the standard VMP. VMPT-VT led to higher response rates and better PFS. No difference in OS was detected between the two arms, but follow-up is still short to draw definitive conclusion. Grade 3-4 neutropenia (38% vs 28%, P=0.02), cardiac complications (10% vs 5%, P=0.04) and thromboembolic events (5% vs 2%, P=0.08) were more frequent with VMPT-VT [35, 36]. The change of bortezomib schedule, from twice-weekly to once-weekly infusion in both arms, improved tolerability of the regimens, reducing peripheral neuropathy incidence to less than 10% and prolonging the time of treatment [37]. A subgroup analysis showed that in patients older than 75 years and in those with high risk disease (according to cytogenetic abnormalities and ISS) a more intensive regimen with VT maintenance does not add any significant advantage (P=0.5). The 1-year landmark analysis of PFS demonstrated that VT reduced the risk of disease progression of 52% (P<0.0001) but this advantage was less evident in patients ≥75 years (P=0.87). A longer follow-up is needed, particularly to assess OS. However, VMP-VT proved to be a valid options, especially for patients aged 65-75 years.

Transplantation with reduced-dose melphalan

Patients older than 65 years, as well as those with significant comorbidities, are generally not considered candidates for standard melphalan 200mg/m2 followed by ASCT. A randomized trial exploring the efficacy of high-dose chemotherapy and transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed MM found a considerably higher 5-year OS in patients younger than 65 years undergoing ASCT compared to elderly patients (68% vs 50%, P=0.008) [38]. Intermediate-dose regimens were proposed to adapt ASCT to older patients, by reducing potentially lethal side effects. Two randomized studies compared reduced-dose melphalan (Melphalan 100mg/m2 – Mel100) followed by ASCT vs MP. The first study included patients between 65 and 70 years, and showed that reduced-intensity ASCT (Mel100) leads to better EFS and OS as compared to MP [39]. The second study included patients aged 65 to 75 years, and compared reduced-intensity ASCT vs MP vs MPT: in this trial, PFS and OS were longer in patients treated with MPT compared with MP or Mel100, and no differences between MP and reduced-intensity ASCT were observed [17]. A phase 2 trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of bortezomib and lenalidomide incorporated in pre-transplant induction and post-transplant consolidation/ maintenance, in patients aged 65-75 years, who received reduced-intensity ASCT (Mel100) [40]. The CR rate was 13% after induction with bortezomib, 43% after Mel100, and 73% during consolidation/maintenance with lenalidomide. During induction therapy, grade 3-4 toxicities were thrombocytopenia (17%), neutropenia (10%), peripheral neuropathy (16%) and pneumonia (10%). Lenalidomide consolidation/ maintenance was well tolerated, with no cumulative or persistent grade 3-4 neutropenia (16%) and/or thrombocytopenia (6%), pneumonia (5%) and skin rash (4%) were the more frequent extra-hematologic toxicities [33]. Data from these studies suggest that the reduced-intensity ASCT is a valuable strategy for elderly patients, for whom full-dose chemotherapy and ASCT may be too toxic. A sequential approach, starting with bortezomib as induction, followed by reduced-intensity ASCT and then lenalidomide consolidation/maintenance, improves response quality and rate. Patients younger than 70 years showed a slightly better outcome compared with patients over 70 years. The incidences of adverse events, early mortality and drop-outs suggest that Mel 100 is more toxic for patients aged 71-75 years and should be considered for patients under 70 years of age.

Therapy for very elderly patients

So far, no precise guidelines are available to strictly define an age cut-off for the choice of treatment. The efficacy of a regimen should always be balanced against its toxicity, and age-adjusted dose modifications are strongly suggested to improve tolerability and treatment outcome (Table 2). Different studies tested the role of reduced-dose regimens in patients over 75 years. The French MPT study investigated reduced-dose of melphalan (0.2 mg/kg) and thalidomide (100 mg/day) in patients older than 75 years [18]. Median PFS was 24.1 months with MPT and OS was 44.0 months. Treatment-related adverse events were acceptable, with a median thalidomide treatment duration over 1 year. No increase in thrombosis was detected, probably thanks to the use of antithrombotic treatments.

Similarly, both the Spanish and the Italian groups showed that, in elderly MM patients, the once-weekly schedule of bortezomib administration reduced toxicity, without negatively impacting on efficacy [34, 37]. This approach led to a significant reduction in non-hematologic grade 3 -4 adverse events, particularly peripheral neuropathy and, consequently, treatment discontinuation rate [37]. On the other hand, the Italian trial showed that the intensive approach with VMP followed by VT maintenance seems not to add any significant advantage in terms of PFS in very elderly patients, over 75 years of age.

Role of maintenance therapy

There are only few studies on the role of maintenance therapy in elderly patients. The Italian group assessed the role of maintenance with VT after VMPT induction. An exploratory analysis performed on the 82 VMPT-VT patients who received at least 6 months of VT maintenance showed an improvement in CR rate from 58% after 9 cycles of VMPT to 62% after 6 months of VT maintenance [35]. The 1-year landmark analysis of PFS demonstrated that VT reduced the risk of disease progression of 52% (P<0.0001) but this advantage was less evident in patients older than 75 years and in those with high risk disease (ISS stage III and adverse genetic profile). A longer follow-up is needed to draw definitive conclusions, especially in terms of OS. The Spanish group investigated the role of maintenance therapy with VP vs VT in elderly patients who had received VMP or VTP as induction. Overall, maintenance treatment improved CR rate (from 25% up to 42%), and no significant differences in response rates between the two maintenance strategies were seen (38% and 46%, respectively with VP and VT). After a median duration of maintenance of 13 months, there was a trend towards a lower TTP with VP compared with VT (1-year TTP: 71% vs 84%; P=0.05), but no significant OS difference was detected (89% with VP vs 92% with VT) [34].

In the European Myeloma Network phase 3 study, after induction with MPR, patients were randomized to receive lenalidomide or placebo maintenance until progression: a landmark analysis showed that lenalidomide maintenance after MPR induction decreased the risk of progression by 69%. The survival advantage was also confirmed in patients older than 75 years [28]. This impressive result lends support to the use of lenalidomide as maintenance therapy.

Longer follow-up is needed to establish the advantage derived from bortezomib and lenalidomide as maintenance therapy in the elderly population.

Conclusion

Today, a wider variety of treatment options are available for both young and elderly patients with MM. In elderly patients, randomized phase 3 studies have shown that MPT and MPV are more effective than the traditional MP and thus they are considered the new standards of care in this setting. The combination MPR followed by lenalidomide maintenance showed to be a valid alternative. Considering the positive preliminary results achieved, MPR followed by lenalidomide maintenance is likely to become an additional standard therapy for elderly MM patients soon. Impressive results were achieved with the more intensive treatment VMPT followed by VT maintenance. Reducing bortezomib -schedule from twice- to once-weekly administration is an appropriate and effective strategy to further improve outcome without negatively affecting efficacy. Recently, reduced-dose dexa-methasone proved to be well tolerated in this population, and Rd may be a valid option for elderly MM patients. ASCT with a reduced melphalan conditioning dose should be considered in selected elderly patients, not older than 70 years. The choice among these regimens should be based on patient characteristics. Patients with renal impairment are eligible for bortezomib or thalidomide-containing regimens, since lenalidomide is excreted by kidneys and, in case of renal impairment, lenalidomide dose must be reduced according to creatinine clearance. If patients suffer from peripheral neuropathy, either myeloma related or not, bortezomib and thalidomide are not the best choice. On the contrary, lenalidomide-containing regimens should be considered for these patients because of the reduced neurologic toxicity associated with lenalidomide.

A particular attention should be paid to alkylating agents and steroids schedule, especially in the very elderly population. In case of treatment -related toxicity, a prompt suspension and subsequent reduction of the drug can limit toxicities.

Thanks to the availability of novel agents, many steps forward have been made in the treatment of elderly MM patients. Phase 2-3 trials including the new generation of IMIDs (Pomalidomide) and proteasome inhibitors (Carfilzomib) are currently ongoing in the elderly population, and their role in this setting may be validated in the near future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editorial assistant Giorgio Schirripa.

Disclosure statement

Antonio Palumbo has received honoraria from Celgene, Janssen-Cilag, Merck, Amgen, and served on the advisory committee for Celgene, Janssen-Cilag.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Recent major improvement in long-term survival of younger patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111:2521–2526. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, Zeldenrust SR, Dingli D, Russell SJ, Lust JA, Greipp PR, Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516–2520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durie BG, Kyle RA, Belch A, Bensinger W, Blade J, Boccadoro M, Child JA, Comenzo R, Djulbegovic B, Fantl D, Gahrton G, Harousseau JL, Hungria V, Joshua D, Ludwig H, Mehta J, Morales AR, Morgan G, Nouel A, Oken M, Powles R, Roodman D, San Miguel J, Shimizu K, Singhal S, Sirohi B, Sonneveld P, Tricot G, Van Ness B, Scientific Advisors of the International Myeloma Foundation Myeloma management guidelines: a consensus report from the Scientific Advisors of the International Myeloma Foundation. Hematol J. 2003;4:379–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Criteria for diagnosis, staging, risk stratification and response assessment of multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2009;23:3–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, Dispenzieri A, Kurtin PJ, Hodnefield JM, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Jelinek DF, Fonseca R, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rajkumar SV. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(25):2582–2590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyle RA, Durie BG, Rajkumar SV, Landgren O, Blade J, Merlini G, Kröger N, Einsele H, Vesole DH, Dimopoulos M, San Miguel J, Avet-Loiseau H, Hajek R, Chen WM, Anderson KC, Ludwig H, Sonneveld P, Pavlovsky S, Palumbo A, Richardson PG, Barlogie B, Greipp P, Vescio R, Turesson I, Westin J, Boccadoro M, International Myeloma Working Group Monoclonal gammo-pathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for progression and guidelines for monitoring and management. Leukemia. 2010;24 doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, Crowley JJ, Barlogie B, Bladé J, Boccadoro M, Child JA, Avet-Loiseau H, Kyle RA, Lahuerta JJ, Ludwig H, Morgan G, Powles R, Shimizu K, Shustik C, Sonneveld P, Tosi P, Turesson I, Westin J. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3412–3420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonseca R, Barlogie B, Bataille R, Bastard C, Bergsagel PL, Chesi M, Davies FE, Drach J, Greipp PR, Kirsch IR, Kuehl WM, Hernandez JM, Minvielle S, Pilarski LM, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Stewart AK, Avet-Loiseau H. Genetics and cytogenetics of multiple myeloma: a workshop report. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1546–1558. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dewald GW, Therneau T, Larson D, Lee YK, Fink S, Smoley S, Paternoster S, Adeyinka A, Ketterling R, Van Dyke DL, Fonseca R, Kyle R. Relationship of patient survival and chromosome anomalies detected in metaphase and/or inter-phase cells at diagnosis of myeloma. Blood. 2005;106:3553–3558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferlay J, Bray F, Pisani P, Parkin DM. IARC CancerBase No. 5, version 2.0. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. GLOBO-CAN 2002: Cancer Incidence. Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myeloma trialists' Collaborative Group. Combination chemotherapy versus melphalan plus prednisone as treatment for multiple myeloma: an overview of 6,633 patients from 27 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3832–3842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.12.3832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple Myeloma. N England J Med. 2004;351:1860–1873. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harousseau JL, Avet-Loiseau H, Attal M, Charbonnel C, Garban F, Hulin C, Michallet M, Facon T, Garderet L, Marit G, Ketterer N, Lamy T, Voillat L, Guilhot F, Doyen C, Mathiot C, Moreau P. Achievement of at least very good partial response is a simple and robust prognostic factor in patients with multiple myeloma treated with high-dose therapy: long-term analysis of the IFM 99-02 and 99-04 Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5720–5726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gay F, Larocca A, Wijermans P, Cavallo F, Rossi D, Schaafsma R, Genuardi M, Romano A, Liberati AM, Siniscalchi A, Petrucci MT, Nozzoli C, Patriarca F, Offidani M, Ria R, Omedé P, Bruno B, Passera R, Musto P, Boccadoro M, Sonneveld P, Palumbo A. Complete response correlates with long-term progression-free and overall survivals in elderly myeloma treated with novel agents: analysis of 1175 patients. Blood. 2011;117:3025–3031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ludwig H, Hajek R, Tòthovà E, Drach J, Adam Z, Labar B, Egyed M, Spicka I, Gisslinger H, Greil R, Kuhn I, Zojer N, Hinke A. Thalidomide-dexamethasone compared with melphalan-prednisolone in elderly patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2009;113:3435–3442. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-169565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Facon T, Mary JY, Hulin C, Benboubker L, Attal M, Pegourie B, Renaud M, Harousseau JL, Guillerm G, Chaleteix C, Dib M, Voillat L, Maisonneuve H, Troncy J, Dorvaux V, Monconduit M, Martin C, Casassus P, Jaubert J, Jardel H, Doyen C, Kolb B, Anglaret B, Grosbois B, Yakoub-Agha I, Mathiot C, Avet-Loiseau H, Inter-groupe Francophone du Myélome Melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide versus melphalan and prednisone alone or reduced-intensity autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly patients with multiple myeloma (IFM 99-06): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1209–1218. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulin C, Facon T, Rodon P, Pegourie B, Benboubker L, Doyen C, Dib M, Guillerm G, Salles B, Eschard JP, Lenain P, Casassus P, Azaïs I, Decaux O, Garderet L, Mathiot C, Fontan J, Lafon I, Virion JM, Moreau P. Efficacy of melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide in patients older than 75 years with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: IFM 01/01 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3664–3670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beksac M, Haznedar R, Firatli-Tuglular T, Ozdogu H, Aydogdu I, Konuk N, Sucak G, Kaygusuz I, Karakus S, Kaya E, Ali R, Gulbas Z, Ozet G, Goker H, Undar L. Addition of thalidomide to oral melphalan/prednisone in patients with multiple myeloma not eligible for transplantation: results of a randomized trial from the Turkish Myeloma Study Group. Eur J Haematol. 2011;86:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waage A, Gimsing P, Fayers P, Abildgaard N, Ahlberg L, Björkstrand B, Carlson K, Dahl IM, Forsberg K, Gulbrandsen N, Haukås E, Hjertner O, Hjorth M, Karlsson T, Knudsen LM, Nielsen JL, Linder O, Mellqvist UH, Nesthus I, Rolke J, Strandberg M, Sørbø JH, Wisløff F, Juliusson G, Turesson I, Nordic Myeloma Study Group Melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide or placebo in elderly patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;116:1405–1412. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wijermans P, Schaafsma M, Termorshuizen F, Ammerlaan R, Wittebol S, Sinnige H, Zweegman S, van Marwijk Kooy M, van der Griend R, Lokhorst H, Sonneveld P, Dutch-Belgium Cooperative Group HOVON Phase III study of the value of thalidomide added to melphalan plus prednisone in elderly patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: the HOVON 49 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3160–3166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Liberati AM, Caravita T, Falcone A, Callea V, Montanaro M, Ria R, Capaldi A, Zambello R, Benevolo G, Derudas D, Dore F, Cavallo F, Gay F, Falco P, Ciccone G, Musto P, Cavo M, Boccadoro M. Oral melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide in elderly patients with multiple myeloma: updated results of a randomized controlled trial. Blood. 2008;112:3107–31014. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palumbo A, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Richardson PG, San Miguel J, Barlogie B, Harousseau J, Zonder JA, Cavo M, Zangari M, Attal M, Belch A, Knop S, Joshua D, Sezer O, Ludwig H, Vesole D, Blade J, Kyle R, Westin J, Weber D, Bringhen S, Niesvizky R, Waage A, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Lonial S, Morgan GJ, Orlowski RZ, Shimizu K, Anderson KC, Boccadoro M, Durie BG, Sonneveld P, Hussein MA. Prevention of thalidomide- and lenalidomide-associated thrombosis in myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:414–423. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fayers PM, Palumbo A, Hulin C, Waage A, Wijermans P, Beksaç M, Bringhen S, Mary JY, Gimsing P, Termorshuizen F, Haznedar R, Caravita T, Moreau P, Turesson I, Musto P, Benboubker L, Schaafsma M, Sonneveld P, Facon T, on behalf of the Nordic Myeloma Study Group. Italian Multiple Myeloma Network. Turkish Myeloma Study Group. Hemato-Oncologie voor Vol-wassenen Nederland. Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome. European Myeloma Network Thalidomide for previously untreated elderly patients with multiple myeloma: meta-analysis of 1685 individual patient data from 6 randomized clinical trials. Blood. 2011;118:1239–1247. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Gregory WM, Russell NH, Bell SE, Szubert AJ, Coy NN, Cook G, Feyler S, Byrne JL, Roddie H, Rudin C, Drayson MT, Owen RG, Ross FM, Jackson GH, Child JA, for the NCRI Haematological Oncology Study Group Cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexa-methasone (CTD) as initial therapy for patients with multiple myeloma unsuitable for autologous transplantation. Blood. 2011;118:1231–1238. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander NS, Fonseca R, Vesole DH, Williams ME, Abonour R, Siegel DS, Katz M, Greipp PR. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as initial therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2010;11:29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70284-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palumbo A, Falco P, Corradini P, Falcone A, Di Raimondo F, Giuliani N, Crippa C, Ciccone G, Omedè P, Ambrosini MT, Gay F, Bringhen S, Musto P, Foà R, Knight R, Zeldis JB, Boccadoro M, Petrucci MT, GIMEMA - Italian Multiple Myeloma Network Melphalan, prednisone, and lenalidomide treatment for newly diagnosed myeloma: a report from the GIMEMA-ltalian Multiple Myeloma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4459–4465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palumbo A, Delforge M, Catalano J, Hajek R, Kropff M, Petrucci MT, Yu Z, Herbein L, Mei JM, Jacques CJ, Dimopoulos MA. A Phase 3 Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Lenalidomide Combined with Melphalan and Prednisone In Patients ≥ 65 Years with Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (NDMM): Continuous Use of Lenalidomide Vs Fixed-Duration Regimens [abstract] Blood. 2010;116:21. Abstract 622. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar SK, Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Stewart K, Buadi FK, Allred J, Laumann K, Greipp PR, Lust JA, Gertz MA, Zeldenrust SR, Bergsagel PL, Reeder CB, Witzig TE, Fonseca R, Russell SJ, Mikhael JR, Dingli D, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A. Lenalidomide, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (CRd) for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: Results from a phase 2 trial. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:640–645. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jagannath S, Durie BGM, et al. Extended follow-up of a phase 2 trial of bortezomib alone and in combination with dexamethasone for the frontline treatment of multiple myeloma. British Journal of Haematology. 2009;146:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, Dimopoulos MA, Shpilberg O, Kropff M, Spicka I, Petrucci MT, Palumbo A, Samoilova OS, Dmoszynska A, Abdulkadyrov KM, Schots R, Jiang B, Mateos MV, Anderson KC, Esseltine DL, Liu K, Cakana A, van de Velde H, Richardson PG, VISTA Trial Investigators Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:906–917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mateos MV, Richardson PG, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, Dimopoulos MA, Shpilberg O, Kropff M, Spicka I, Petrucci MT, Palumbo A, Samoilova OS, Dmoszynska A, Abdulkadyrov KM, Schots R, Jiang B, Esseltine DL, Liu K, Cakana A, van de Velde H, San Miguel JF. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone compared with melphalan and prednisone in previously untreated multiple myeloma: updated follow-up and impact of subsequent therapy in the phase III VISTA trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(13):2259–2266. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harousseau JL, Palumbo A, Richardson PG, Schlag R, Dimopoulos MA, Shpilberg O, Kropff M, Kentos A, Cavo M, Golenkov A, Komarnicki M, Mateos MV, Esseltine DL, Cakana A, Liu K, Deraedt W, van de Velde H, San Miguel JF. Superior outcomes associated with complete response in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients treated with nonintensive therapy: analysis of the phase 3 VISTA study of bortezomib plus melphalan-prednisone versus melphalan-prednisone. Blood. 2010;116:3743–3750. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mateos MV, Oriol A, Martínez-López J, Gutiérrez N, Teruel AI, de Paz R, García-Laraña J, Bengoechea E, Martín A, Mediavilla JD, Palomera L, de Arriba F, González Y, Hernández JM, Sureda A, Bello JL, Bargay J, Peñalver FJ, Ribera JM, Martín-Mateos ML, García-Sanz R, Cibeira MT, Ramos ML, Vidriales MB, Paiva B, Montalbán MA, Lahuerta JJ, Bladé J, Miguel JF. Bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone versus bortezomib, thalidomide, and prednisone as induction therapy followed by maintenance treatment with bortezomib and thalidomide versus bortezomib and prednisone in elderly patients with untreated multiple myeloma: a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:934–941. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70187-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Rossi D, Cavalli M, Larocca A, Ria R, Offidani M, Patriarca F, Nozzoli C, Guglielmelli T, Benevolo G, Callea V, Baldini L, Morabito F, Grasso M, Leonardi G, Rizzo M, Falcone AP, Gottardi D, Montefusco V, Musto P, Petrucci MT, Ciccone G, Boccadoro M. Bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide followed by maintenance with bortezomib-thalidomide compared with bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5101–5109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.8216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Cavalli M, Ria R, Offidani M, Patriarca F, Nozzoli C, Guglielmelli T, Benevolo G, Callea V, Zambello R, Pietrantuono G, De Rosa L, Liberati AM, Crippa C, Perrone G, Ciambelli F, Carella AM, Palmieri S, Gilestro M, Magarotto V, Petrucci MT, Musto P, Gaidano G, Boccadoro M. Bortezomib, Melphalan, Prednisone and Thalidomide Followed by Maintenance with Bortezomib and Thalidomide (VMPT-VT) for Initial Treatment of Elderly Multiple Myeloma Patients: Updated Follow-up and Impact of Prognostic Factors [abstract] Blood. 2010;116:21. Abstract 620. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bringhen S, Larocca A, Rossi D, Cavalli M, Genuardi M, Ria R, Gentili S, Patriarca F, Nozzoli C, Levi A, Guglielmelli T, Benevolo G, Callea V, Rizzo V, Cangialosi C, Musto P, De Rosa L, Liberati AM, Grasso M, Falcone AP, Evangelista A, Cavo M, Gaidano G, Boccadoro M, Palumbo A. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly bortezomib in multiple myeloma patients. Blood. 2010;116:4745–4753. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barlogie B, Tricot G, Anaissie E, Shaughnessy J, Rasmussen E, van Rhee F, Fassas A, Zangari M, Hollmig K, Pineda-Roman M, Lee C, Talamo G, Thertulien R, Kiwan E, Krishna S, Fox M, Crowley J. Thalidomide and hematopoietic-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Enlg J Med. 2006;354:1021–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Petrucci MT, Musto P, Rossini F, Nunzi M, Lauta VM, Bergonzi C, Barbui A, Caravita T, Capaldi A, Pregno P, Guglielmelli T, Grasso M, Callea V, Bertola A, Cavallo F, Falco P, Rus C, Massaia M, Mandelli F, Carella AM, Pogliani E, Liberati AM, Dammacco F, Ciccone G, Boccadoro M. Intermediate-dose melphalan improves survival of myeloma patients aged 50 to 70: results of a randomized controlled trial. Blood. 2004;104:3052–3057. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palumbo A, Gay F, Falco P, Crippa C, Montefusco V, Patriarca F, Rossini F, Caltagirone S, Benevolo G, Pescosta N, Guglielmelli T, Bringhen S, Offidani M, Giuliani N, Petrucci MT, Musto P, Liberati AM, Rossi G, Corradini P, Boccadoro M. Bortezomib as induction before autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide as consolidation-maintenance in untreated multiple myeloma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:800–807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]