Abstract

Background

Everyday clinical practice requires knowledge of medical ethics and the taking of moral positions. We investigated the ethical knowledge and attitudes of a representative sample of physicians with regard to end-of-life decisions, euthanasia, and the physician-patient relationship.

Methods

192 physicians (96 women, 96 men; mean age 50) in a random sample of Bavarian physicians completed our structured questionnaire. Data were collected from September to November 2010.

Results

There was much uncertainty among the respondents about the relevant knowledge for end-of-life decisions and the implementation of existing guidelines and laws on euthanasia and advance directives. Attitudes to ethical questions were found to be correlated with the length of time the physicians had been in practice.

Conclusion

Physicians’ personal values and moral attitudes play a major role in clinical decision-making. We used a questionnaire to examine physicians’ opinions about end-of-life issues and to determine the factors that might influence them. We found their knowledge of medical ethics to be inadequate. Competence in medical ethics needs to be strengthened by more ethical teaching in medical school, specialty training, and continuing medical education.

Knowledge of medical ethics and the taking of moral positions are an essential part of everyday clinical practice. Particularly in borderline situations such as decisions about limiting therapy, fundamental values of the practice of medicine—such as respecting patient autonomy and responsibility for appropriate decisions about treatment—must be upheld (1– 3). In clinical practice, the informed consent process serves to fulfill these requirements and enable patients to make their own decisions. Personal values, moral positions, and knowledge of medical ethics are of essential importance for shared decision-making processes (4, 5). In addition to guidelines and laws, professional ethical principles guide and underpin a capacity for critical judgment, to ensure decisions about treatment are well grounded and appropriate.

Previous publications have discussed what principles and guidelines might serve as guides in everyday clinical practice (6, 7). The present study investigates knowledge of medical ethics among doctors, and how far doctors are competent to make ethical decisions as individuals. Another part of the study is concerned with moral positions on medical ethical questions and problems in the course of clinical work.

Methods

Study design, questionnaire development, and contents of the survey instrument

For the purpose of the investigation, a panel study and a structured questionnaire were developed. These modules were guided by methodological considerations and validated measuring instruments from other survey studies (5, 8– 13). Question design was based on items that had already been used to survey medical students. They were further adapted to the requirements of surveying doctors by means of a pretest, to reduce confounding factors and optimize construct validity.

The questionnaire was sent out to 500 doctors throughout Bavaria. Study participants were chosen on the basis of a random sample. Data were collected in this first cross-sectional survey from September to November 2010. All question items were assessed using a five-point Likert scale, from 1 “agree entirely” to 5 “disagree entirely.” There was also an answer category “don’t know.” To improve interpretability of the results, answer categories 1 and 2 were assessed as agreement, 3 as undecided, and 4 and 5 as disagreement.

The questionnaire included 71 items and was divided into two sections: demographic as well as moral and ethical. The moral/ethical section contained case examples on medical ethical questions and problems and on knowledge about assisted dying and the Law on Advance Health Care Directives (Patientenverfügungsgesetz) of 1 September 2009. Other items tested consistency of answering behavior. The demographic part of the questionnaire collected personal data about the respondent.

Statistical analysis

Statistical software (PASW Statistics, version 18) was used for data evaluation. The chi square (χ2) and Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rs) were used to analyze bivariate relationships. For greater clinical ease of use and more practical presentations of results, we divided the doctors into two groups of roughly equal size: one of those with up to 20 years’ experience of medical practice (56%, n = 109) and the other of those with more than 20 years’ experience (44%, n = 76). Based on this division, two-sided significance tests were performed. Resulting p values smaller than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. In order to estimate the development of moral positions in dependence on professional experience, correlation analyses were performed between the length of medical practice at 5-year intervals and the strength of moral positions, each recorded using a five-point Likert scale. Results are described in the form of mean, standard deviation (SD), and median, together with percentages for agreement and disagreement.

Results

Characteristics of respondents

A total of 192 completed questionnaires were returned, giving a response rate of 38%. Men and women responded in equal proportions (50%, n = 96, for each). Mean age was 50±14 years (men: 53±14 years, women: 47±14 years, range: 25–97 years).

Knowledge of medical ethics

By medical ethics the authors mean primarily respect for patient autonomy (not a self-evident principle of medical ethics), knowledge about end-of-life issues, assisted dying, and the doctor–patient relationship. The section on knowledge of medical ethics was headed by a case example (Box).

Box. Case example in the questionnaire.

The aim of the advance health care directive is to express and validate the will of the patient regarding his or her health care after he or she has ceased to be able to do so in person. “A 55-year-old man suffers a serious car accident and has since been lying in a coma. He was admitted as an emergency and is now being artificially ventilated. It is currently being considered whether also to feed him artifically via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). In his advance directive for such a case the patient has said that he does not wish for any life-prolonging procedures (ventilation, nutrition).” How do you assess the following statements?

| Agree completelyDisagree completely | Don’t know | |||||

| A) A PEG should be placed in this patient. | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| B) In this case the patient’s ventilator should be switched off. | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| My decision regarding A and B depends on the patient’s prognosis. | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο | Ο |

| In your opinion, what kind of assisted dying is involved in the following two steps? | ||||||

| A) A PEG is not placed. | Ο Passive assisted dyingΟ Don’t know | Ο Active assisted dying | ||||

| B) The patient’s ventilator is switched off. | Ο Passive assisted dyingΟ Don’t know | Ο Active assisted dying | ||||

The first two items tested whether respondents would comply with a patient’s wishes regarding limitation of treatment in an advance directive. Most doctors would not place a gastric tube (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, PEG) (mean = 3.8±1.5; median = 5; agreement = 20%; disagreement = 51%), but would maintain ventilation (mean = 3.4±1.6; median = 4; agreement =25%; disagreement = 41%). Most respondents said their decision would depend on the patient’s prognosis (mean = 1.7±1.6; median = 1; agreement = 80%; disagreement = 11%).

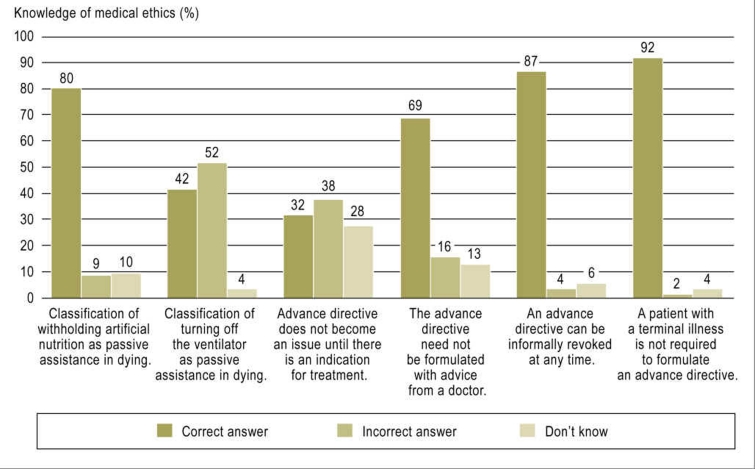

In addition, respondents were asked to categorize the two management options—withholding artificial nutrition and withdrawing ventilation—as active or passive assistance in dying. The former was correctly classified by 80% of respondents (95% confidence interval [CI]: 73 to 85; n = 153) as passive assistance. However, switching off the ventilator was inaccurately classified by 52% of respondents (95% CI: 45 to 59, n = 100) as active assistance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution (percentages) of answers to questions about knowledge of medical ethics in the area of assisted dying and advance health care directives; where totals do not add up to 100% this is due to rounding or to missing answers (max. 4%)

One set of questions measured respondents’ knowledge of the Law on Advance Health Care Directives of 1 September 2009. The statement that the patient’s wish is only taken into account when treatment is indicated was answered by 32% (95% CI: 26 to 39, n = 62) as correct, by 38% as incorrect, and 28% said they did not know. The other questions about the Law on Advance Decisions were correctly answered by most respondents.

Moral positions on assisted dying

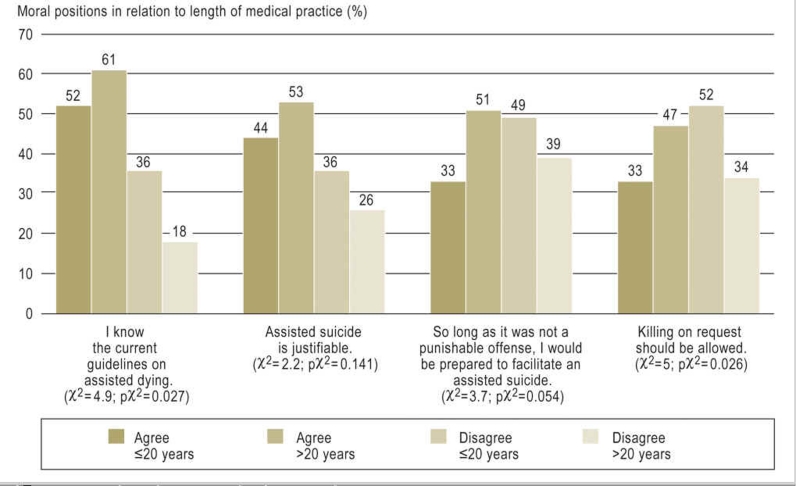

Attitudes to end-of-life issues showed a significant correlation between length of medical practice in years and answers (Table). The longer respondents had been in practice, the more they saw assisted dying as a mean of alleviating suffering (ps<0.001; rs = –0.28). Those who had been in practice for longer were also more open-minded about the question of whether assisted suicide could be justified (ps = 0.018; rs = –0.18). They also tended to be more ready to facilitate assisted suicide themselves (ps = 0.047; rs = –0.15). They were also more likely to answer yes to the question whether under certain circumstances “killing on request” should be permitted (ps = 0.008; rs = –0.21). Those who had been in practice for longer gave a higher estimate of their knowledge of the guidelines on assisted dying (ps<0.001; rs = –0.34) and the Law on Advance Health Care Directives (ps<0.001; rs = –0.41) than did their less experienced colleagues, but this difference was not reflected in the knowledge they demonstrated. These findings are summarized in Figure 2.

Table. Moral positions on a five-point Likert scale in relation to length of practice of medicine (5-year intervals).

| Moral position | Spearman rho (rs) | p value (ps) |

| Assisted dying | ||

| I am familiar with the most recent legislation in Germany on advance health care directives. | –0.41 | <0.001 |

| I know the current guidelines on assisted dying. | –0.34 | <0.001 |

| For me, assisted dying is an expression of the doctor’s responsibility to alleviate suffering. | –0.28 | <0.001 |

| I regard it as ethically justifiable for patients to be supported in their decision to die, e.g., by being given medical drugs. | –0.18 | 0.018 |

| I would be prepared to offer this support so long as it were not a punishable offense. | –0.15 | 0.047 |

| "Killing on request" should be made possible in exceptional cases, when the person concerned is unable to act him- or herself but is able to make his or her wishes known. | –0.21 | 0.008 |

| Doctor–patient relationship | ||

| The doctor should assume responsibility and authority for decisions in the best interests of the patient’s well-being. | –0.06 | 0.424 |

| As the expert adviser, the doctor is co-responsible for ensuring that patient decisions are as appropriate as possible. | –0.1 | 0.165 |

| The doctor provides competent specialist services—neither more nor less. | 0.09 | 0.227 |

| Patients have little understanding of the consequences of therapeutic decisions | –0.25 | 0.001 |

Figure 2.

Distribution (percentages) of agreement and disagreement with moral positions on assisted dying in relation to length of medical practice

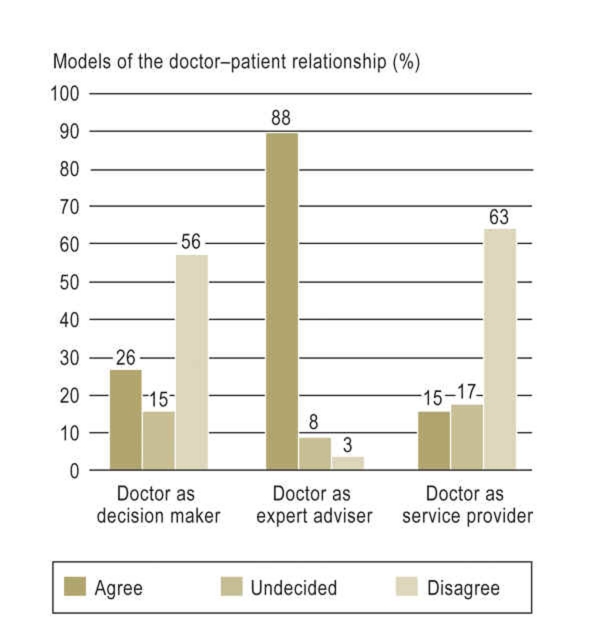

Moral positions on the doctor–patient relationship

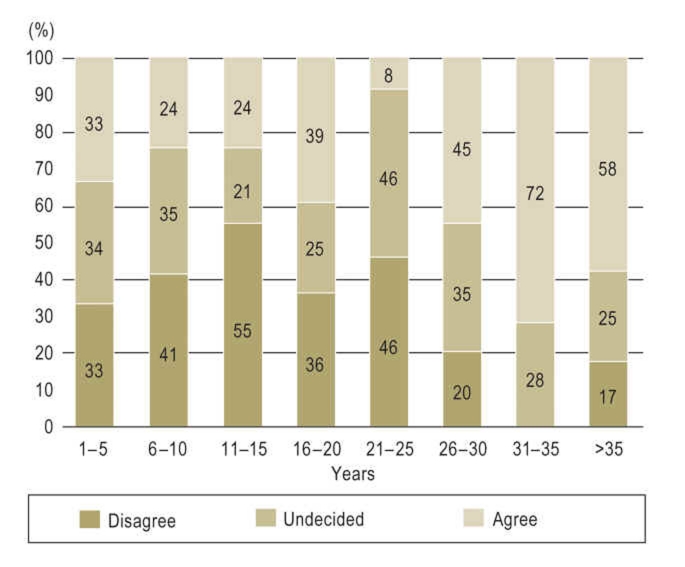

Attitudes about the doctor–patient relationship (Figure 3) did not correlate greatly with length of medical practice. The majority preferred a model of the doctor–patient relationship in which the doctor contributed to appropriate treatment decisions as an expert adviser (mean = 1.5±0.8; median = 1; agreement = 88%; disagreement = 3%). The models of the doctor as a service provider (mean = 3.8±1.2; median = 4; agreement = 15%; disagreement = 63 %) or as a paternalistic figure both tended to be rejected (mean = 3.6±1.4; median = 4; agreement = 26%; disagreement = 56%). Attitudes to the statement that patients have a limited capacity to understand the consequences of treatment decisions varied (mean = 2.9±1.2; median = 3; agreement = 37%; disagreement = 32%) (Figure 4). Doctors who had been in practice for a long time agreed with this statement more often than did their less-experienced colleagues (ps = 0.001; rs = –0.25).

Figure 3.

Distribution (percentages) of attitudes amongst doctors to the various models of the doctor–patient relationship; where totals do not add up to 100% this is due to rounding or to missing answers (max. 5%)

Figure 4.

Distribution (percentages) of attitudes to the statement that patients have little understanding of the consequences of therapeutic decisions, in relationship to years of professional experience (5-year intervals)

Discussion

Knowledge of medical ethics

Improvements in the medical care of patients have opened up new possibilities in prolonging the life span and maintaining life, e.g., in comatose patients. The increased demands on competence in medical ethics that are entailed by these new possibilities require, not just particular specialist qualifications, but also a knowledge of the fundamental principles of ethics (4). As other empirical studies have shown, there is great uncertainty about how to classify medical procedures in respect of the various forms of assisted dying (14, 15). The majority of doctors surveyed were unable to correctly classify turning off a ventilator as passive assistance in dying. The feeling of being responsible for a patient’s death through having withdrawn a medical treatment is an extremely important factor in whether an action of assistance in dying is correctly or incorrectly classified (16, 17). In 2006 the German National Ethics Council (Deutscher Ethikrat) pointed out that the terms “active assisted dying” and “passive assisted dying” are misleading and should in future be replaced by more precise terms such as “allowing to die” and “killing on request”.

The results of the present study demonstrate that lack of knowledge can affect decision making in an actual case example. Although doctors attach great importance to patients’ advance directives (5, 18), the decision about limiting treatment was made dependent on prognostic criteria, not on the patient’s wishes as expressed in the advance directive. In addition to the uncertainty about the law, the medical ethical conflict between the principles of maintaining health (doing good) and self-determination for the patient (autonomy) may have induced the doctors to disregard the patient’s wishes in the case example given. Unless the doctor has reason to doubt that the existing advance directive applies to the given situation in terms of the patient’s life and treatment, he or she should comply with the patient’s directive.

In addition, it became evident that knowledge of a central part of the new law on patient advance directives, the part relating to medical indication, was inadequate (19). This part provides that the question of the patient’s wishes does not arise until medical treatment is indicated. If medical opinion is that no medical treatment is indicated, e.g., to achieve a particular therapeutic goal, the question about the patient’s wishes in relation to this does not need to be asked. Despite the legal clarification of 1 September 2009 about how to deal with advance directives, the clarity thus achieved in law is not reflected in the doctors’ decisions.

Guidelines on end-of-life care and on dealing with advance health care directives are essential to protect patient autonomy in clinical decision-making processes. The findings of the present study show deficits in handling decisions about limiting treatment and about implementing the legal implications of statements of intent that have relevance for (medical management) actions and for further education and training. Medical training courses at all levels would contribute to strengthening doctors’ ethical skills. Firstly, they would transmit knowledge about medical ethics and legal issues; and, secondly, in the process, they would enable the development of communication skills and an ability to analyze ethical questions (case analysis). This form of training will enable the development of a professional attitude toward medical ethical questions.

Moral positions

Therapeutic decision-making processes are influenced not only by professional medical knowledge, but also by personal moral attitudes. For this reason it is important to make visible doctors’ moral positions on end-of-life questions and problems and the factors that influence them. Respondents’ answers should be viewed in light of the knowledge that there can be a difference between what a person states his or her moral position to be (self-evaluation) and his or her actual position (evaluation by another). The present findings show a clear correlation between experience in the practice of medicine and various moral positions. A correlation was demonstrated in particular in questions about subjective estimation of the respondent’s own state of knowledge. More doctors who have been practicing for longer feel that assisted suicide is justifiable and support this, which is in contrast to other findings (20). This observation may be ascribable to their own aging, and to a related increased sympathy with end-of-life situations. However, analysis of factors influencing the development of moral positions can only be done as part of the panel study.

In parallel with the development of medical technology, views of the doctor–patient relationship are changing (21, 22). Survey respondents were asked to assess statements corresponding to, respectively, the paternalistic model, the sharing model, and the informational model (23). The analysis of preferences regarding the doctor–patient relationship showed no difference in relation to how long the respondents had been in medical practice. The large majority of doctors surveyed were in favor of the partnership model of the doctor–patient relationship. The only difference was in the assessment of whether patients understood the consequences of therapeutic decisions. Doctors of longer professional experience had a poorer opinion of patients’ capacities in medical questions than colleagues with a shorter experience of practicing medicine. Whether this observation is due to a received paternalistic understanding of roles must remain a subject for future research.

It emerged that patient autonomy does not play the main role in terms of either the patient advance health care directive or the doctor–patient relationship. The fact that doctors who have been practicing for longer believe that patients have little comprehension of the consequences of therapeutic decisions could well be related to the limited role ascribed to patient autonomy in the view of the doctors surveyed.

Discussion of method

A random sample was taken from the totality of all Bavarian doctors. The study participants identified in this way were sent a questionnaire by mail. The response rate of 38%, a good rate for studies of this kind (10, 12, 13). The observed findings are subject to various possible limitations. We did not adjust p values for multiple testing, so a higher probability of type I error is possible (24). Failure to respond may be due to lack of time (nonresponse bias) and to differences in the perceived importance of the topic (selection bias) and may lead to systematic distortion. Effects such as tending toward the mean and social desirability cannot be ruled out with certainty. We attempted to counteract these influences by appropriate survey design and carrying out a pretest.

Summary

Personal values, moral positions, and knowledge of medical ethics are extremely important in the joint decision-making process of the patient–doctor interaction. In borderline situations such as decisions about limiting treatment, doctors should be guided by patient preferences. This is why it is important to demonstrate the moral positions of doctors in relation to end-of-life questions and problems, and to identify other influential factors as part of a critical reflection on decision-making processes.

The present survey demonstrates fundamental deficits in the knowledge of respondents, and these deficits affected the quality of their therapeutic decisions in the case example they were given. To strengthen the individual ethical competence of doctors, the authors see an increased need for training at all levels of medical education in questions and problems in the area of medical ethics and law.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Johanna Huber and Matthias Holzer (Teaching of Medicine, Medizinische Klinik-Innenstadt, Ludwig-Maximilians University) for advice.

This article was written in the course of work for Jana Wandrowski’s medical dissertation.

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff, MA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Beauchamp T, Childress J. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.; 2008. Principles of biomedical ethics. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalla-Vorgia P, Lascaratos J, Skiadas P, Garanis-Papadatos T. Is consent in medicine a concept only of modern times? J Med Ethics. 27:59\–61. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rauprich O, Steger F, editors. Moralphilosophie und medizinische Praxis. Frankfurt/M., New York: Campus; 2005. Prinzipienethik in der Biomedizin. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ethikberatung in der klinischen Medizin. Stellungnahme der Zentralen Kommission zur Wahrung ethischer Grundsätze in der Medizin und ihren Grenzgebieten. Dtsch Arztebl. 2006;103(24):A 1703–A 1707. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oorschot B, Lipp V, Tietze A, Nickel N, Simon A. Einstellungen zur Sterbehilfe und zu Patientenverfügungen - Ergebnisse einer Ärztebefragung. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004;130:261–265. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ollenschläger G, Oesingmann U, Thomeczek C, Kolkmann FW. Ärztliche Leitlinien in Deutschland - aktueller Stand und zukünftige Entwicklungen. Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich. 1998;92:273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartels S, Parker M, Hope T, Reiter-Theil S. Wie hilfreich sind „ethische Richtlinien“ am Einzelfall? (Eine vergleichende kasuistische Analyse der Deutschen Grundsätze, Britischen Guidelines und Schweizerischen Richtlinien zur Sterbebegleitung) Ethik Med. 2005;17:191–205. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strube W, Pfeiffer M, Steger F. Moralische Positionen, medizinethische Kenntnisse und Motivation im Laufe des Medizinstudiums - Ergebnisse einer Querschnittsstudie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. Ethik Med. 2011;23:201–216. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harfst A. Allgemeinärztliche Beurteilung und Einstellungen zur Sterbehilfe (Eine nationale Erhebung) Diss. Göttingen. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber M, Stiehl M, Reiter J, Rittner C. Ethische Entscheidungen am Ende des Lebens: Sorgsames Abwägen der jeweiligen Situation. Dtsch Arztebl. 2001;98(48):A 3184–A 3188. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schildmann J, Hermann E, Burchardi N, Schwantes U, Vollmann J. Sterbehilfe. Kenntnisse und Einstellungen Berliner Medizinstudierender. Ethik Med. 2004;16:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurst S, Perrier A, Pegoraro, et al. Ethical difficulties in clinical practice: experiences of European doctors. J Med Ethics. 2007;33:51–57. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.014266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hariharan S, Jonnalagadda R, Walrond E, Moseley H. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of healthcare ethics and law among doctors and nurses in Barbados. BMC Medical Ethics. 2006;7 doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Csef H, Hendl R. Einstellungen zur Sterbehilfe bei deutschen Ärzten. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:1501–1506. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck S, van de Loo A, Reiter-Theil S. A „’little bit illegal’’? Withholding and withdrawing of mechanical ventilation in the eyes of German intensive care physicians. Med Health Care and Philos. 2008;11:7–16. doi: 10.1007/s11019-007-9097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farber N, Simpson P, Salam T, Collier V, Weiner J, Boyer E. Physicians’ Decisions to Withhold and Withdraw Life-Sustaining Treatment. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:560–564. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin P, Sprung C. Withdrawing and withholding life-sustaining therapies are not the same. Crit Care. 2005;9:230–232. doi: 10.1186/cc3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oorschot B, Schweitzer S. Ambulante Versorgung von Tumorpatienten im finalen Stadium. DMW. 2003;128:2295–2299. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-43188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Empfehlungen der Bundesärztekammer und der Zentralen Ethikkommission bei der Bundesärztekammer zum Umgang mit Vorsorgevollmacht und Patientenverfügung in der ärztlichen Praxis. Dtsch Arztebl. 2010;107(18):A 877–A882. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon A. Einstellung der Ärzte zur Suizidbeihilfe: Ausbau der Palliativmedizin gefordert. Dtsch Arztebl. 2010;107(28-29) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stellungnahme der Zentralen Kommission zur Wahrung ethischer Grundsätze in der Medizin und ihren Grenzgebieten (Zentrale Ethikkommission) bei der Bundesärztekammer „Werbung und Informationstechnologie Auswirkungen auf das Berufsbild des Arztes“. Dtsch Arztebl. 2010;107(42):A 518–A 523. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geisler L Deutscher Bundestag. Schlussbericht der Enquete-Kommission Recht und Ethik der modernen Medizin. Opladen: 2002. Arzt-Patient-Beziehung im Wandel - Stärkung des dialogischen Prinzips; pp. 473–481. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charles C, Whelan T, Gafni A. What do we mean by partnership in making decisions about treatment? BMJ. 1999;319:780–782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saville D. Multiple Comparison Procedures: The Practical Solution. Am Stat. 1990;44:174–180. [Google Scholar]