Abstract

It is agreed that conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spine is one of the core elements in the differential diagnostic work up of patients with clinical signs of motor neuron diseases (MNDs), for example amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), to exclude MND mimics. However, the sensitivity and specificity of MRI signs in these disorders are moderate to low and do not have an evidence level higher than class IV (good clinical practice point). Currently computerized MRI analyses in ALS and other MNDs are not techniques used for individual diagnosis. However, they have improved the anatomical understanding of pathomorphological alterations in gray and white matter in various MNDs and the changes in functional networks by quantitative comparisons between patients with MND and controls at group level. For multiparametric MRI protocols, including T1-weighted three-dimensional datasets, diffusion-weighted imaging and functional MRI, the potential as a ‘dry’ surrogate marker is a subject of investigation in natural history studies with well defined patients. The additional value of MRI with respect to early diagnosis at an individual level and for future disease-modifying multicentre trials remains to be defined. There is still the need for more longitudinal studies in the very early stages of disease or when there is clinical uncertainty and for better standardization in the acquisition and postprocessing of computer-based MRI data. These requirements are to be addressed by establishing quality-controlled multicentre neuroimaging databases.

Keywords: motor neuron diseases, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, MRI, T1-weighted imaging, DTI

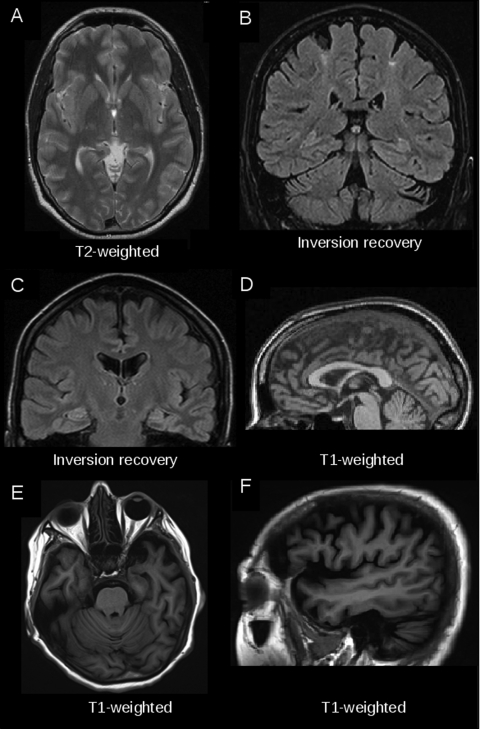

Diagnostic role of neuroimaging in motor neuron diseases

There is consensus among clinicians who care for patients with motor neuron diseases (MNDs) that routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spine is one of the core elements of the differential diagnostic work up. In particular, in the most common adult MND, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), it is crucial to use MRI to investigate (and exclude) conditions that might mimic upper motor neuron (UMN) or lower motor neuron (LMN) dysfunction or even their combination. A characteristic example of a combination is cervical spinal column degeneration that might result in combined clinical lesions of the UMN via cervical myelopathy and of the LMN via radiculopathy [Comi et al. 1999]. In the literature, there are few MRI signs reported that might support the diagnosis directly. In this context, hyperintensities of the corticospinal tract (CST) in the brain or sometimes in the spinal cord have been described; in addition, atrophy of the precentral gyrus or hypointensities in the precentral gyrus, that is, the ‘motor dark line’ in T2-weighted (T2w) images [Grosskreutz et al. 2008]. Signal shortening of the motor cortex in T2w MRI has also been reported, but the origin is unknown because T2w MRI did not demonstrate signal shortening [Hecht et al. 2005]. In proton-density images, foci of frontal abnormalities were observed, indicating involvement of frontal projections. In addition, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images were slightly more sensitive in detecting CST signal alterations than T1w or T2w images (see Grosskreutz and colleagues for a review) [Grosskreutz et al. 2008]. Also for the diagnosis of primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), MRI signs are described, that is, abnormalities (atrophy) in the precentral gyrus region and CST hyperintensities [Singer et al. 2007]. In ALS and PLS, changes in the corpus callosum were described at individual and group level (see below). Exemplary images of these findings in ALS and PLS are given in Figure 1(A–D). In all reviews of the literature and meta-analyses, however, it is agreed that the sensitivity and specificity of all the signs mentioned are moderate to low [Comi et al. 1999; Grosskreutz et al. 2008; Turner et al. 2009], and none of the MRI-based signs had a higher evidence level than 2 in an evidence-based analysis by Chan and colleagues [Chan et al. 2003].

Figure 1.

Examples of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in individual patients with motor neuron disease. (A) T2-weighted MRI hyperintensity along the corticospinal tract (axial view, at the level of the posterior limb of the internal capsule) in a 62-year-old patient with clinically definite amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). (B) Regional motor cortex atrophy and signal alterations in the adjacent centrum semiovale in a coronal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) image in a 50-year-old patient with primary lateral sclerosis (PLS). (C) Symmetrical hyperintensities along the pyramidal tracts in a coronal FLAIR image of a 64-year-old patient with PLS. (D) Regional atrophy of the motor segment of the corpus callosum in T1-weighted MRI (sagittal slice) in a 53-year-old patient with ALS. (E, F) Marked frontotemporal atrophy (T1-weighted MRI in axial and sagittal view) in a 54-year-old patient with advanced ALS frontotemporal lobar degeneration complex.

In early imaging studies, techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) were used to address the basic metabolic turnover in the human cortex or task-related blood flow changes in MNDs. Hypometabolism and hypoperfusion were repeatedly observed in the cortex of patients with MND during rest, and in patients with ALS this was most prominent in the motor cortex extending to frontal areas to varying degrees depending on the study [e.g. Tanaka et al. 2003]. By using the tracer 11C-flumazenil-PET as a benzodiazepine GABAA marker, Lloyd and colleagues found evidence for the involvement of motor, premotor, frontal and associative cortical areas in 17 patients without dementia with clinically probable or definite ALS [Lloyd et al. 2000]. The potential of PET and SPECT in diagnosis and as surrogate markers of disease expression and progression was never fully realized [Turner and Leigh, 2000]. This is because with the growing availability of MRI scanners in many clinics and research centers, the invasive character of neuroimaging for patients was decreased to a minimum so that MRI became the routine technique for clinical and neuroscientific neuroimaging in MNDs.

Magnetic resonance imaging guidelines

The European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) guidelines on neuroimaging of MNDs (which were designed to provide practical help for neurologists to make appropriate use of neuroimaging techniques in patients with MNDs) are focused on MRI-based neuroimaging techniques [Filippi et al. 2010]. For standard conventional MRI techniques, the following two basic recommendations are given. First, all patients suspected of having MND, where a plausible alternative explanation of an underlying pathology of the clinical presentation exists, should receive an MRI examination of either or both the brain and whole spinal cord depending on the clinical presentation, with an evidence level class IV, stated as a good clinical practice point (GCPP) since a consensus was reached despite this lack of evidence. Second, the detection of CST hyperintensities on T2w, proton density or FLAIR imaging and a T2-hypointense rim in the precentral gyrus can support a pre-existing suspicion of ALS. With respect to the low sensitivity and specificity of such abnormalities and the weak correlation with clinical findings as detailed above, the specific search of these abnormalities for the purpose of making a firm diagnosis of ALS is not recommended (class IV, level GCPP).

Computer-based magnetic resonance imaging: structural analysis

Given these limitations of routine MRI, advanced MRI techniques have been applied to ALS and other MNDs, including volumetric or morphometric analyses of T1w three-dimensional MRI data and analyses of diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and its further applications [Agosta et al. 2010]. Early MRI-based studies were focused on region of interest-based volumetry of the motor system in patients with MND [Wang and Melhem, 2005]. Several later studies used the whole brain-based approach of voxel-based morphometry (VBM), which compares neuroanatomical differences on a voxelwise basis in spatially normalized MRI datasets between groups of subjects. In ALS, VBM studies demonstrated volume changes at group level in classical motor areas such as the primary motor cortex and changes in white matter areas such as the CST [Kassubek et al. 2005]. In addition, patients with ALS with features of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) demonstrated atrophy in the frontotemporal cortices [Chang et al. 2005]. As detailed in the review by Grosskreutz and colleagues [Grosskreutz et al. 2008], it is important to note that patients with ALS and neuropsychological deficits or fulfilling the diagnostic criteria of the ALS/FTLD complex often showed atrophy of frontal and temporal areas which might be marked in advanced stages and is then obvious on individual MRIs, as demonstrated in Figure 1(E, F). However, frontal volume reductions were also observed in patients with ALS without overt neuropsychological deficits, albeit inconsistently. Volumetric studies of the spinal cord in MNDs are rare and showed heterogeneous results. One longitudinal study showed a significant development of cord atrophy over a 9-month follow up at group level [Agosta et al. 2007].

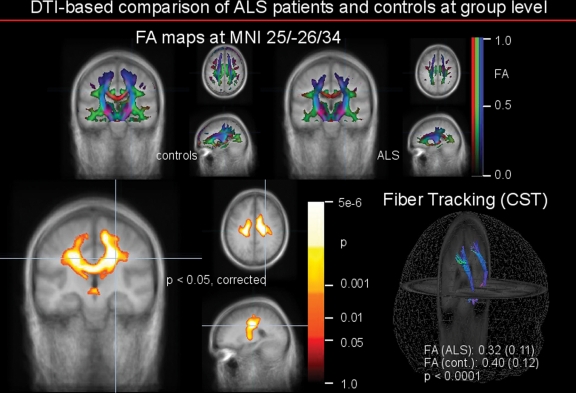

Computer-based magnetic resonance imaging: diffusion tensor imaging

White matter tract alterations in MNDs have been investigated in a rapidly growing number of studies using DWI and the computer-based analysis of DWI data using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI). DWI is based on the diffusion of water which is influenced by local tissue properties. DWI sequences combine several gradient directions, each of which codes the diffusion along its direction so that DTI characterizes the combination of diffusion directions in each voxel [Basser and Jones, 2002]. The resulting tensor shape information can be converted into compound measures such as fractional anisotropy (FA) to compare groups and to correlate clinical markers with imaging data. DTI has been established as a robust noninvasive technical tool to investigate in vivo neuropathology of white matter neuronal tracts [Müller et al. 2011a]. In ALS, DTI techniques have demonstrated regional pathology mainly along the CST [Sach et al. 2004]. However, recent studies described findings that reached into adjacent subcortical white matter, across the corpus callosum and into frontal subcortical areas [e.g. Sage et al. 2009], in accordance with the frontotemporal (cortical) changes in volumetry. In particular, the corpus callosum was identified as one element of MRI-visible changes in ALS and other MNDs using DTI-based techniques (Figure 2), in accordance with regional atrophy which might be observed in individual MRI scans [Figure 1(D)]. In a recent study in patients with ALS, FA reduction was demonstrated in the corpus callosum, extending rostrally and bilaterally to the region of the primary motor cortices, independent of the degree of clinical UMN involvement. However, a matched regional increase in another DTI readout, that is radial diffusivity, supported the concept of anterograde degeneration of callosal fibers [Filippini et al. 2010]. In particular, the motor segment, that is segment II according to the Hofer and Frahm scheme, shows MND-associated alterations. Therefore, DTI-based methods seem to be a valuable tool for guiding the pathoanatomy definition of MND subtypes. In addition, the corpus callosum seems to be a key structure in the regional degeneration pattern in MNDs with a predominance of UMN affectation including PLS [Unrath et al. 2010, 2011] and pure and complicated hereditary spastic paraparesis variants [Kassubek et al. 2007; Müller et al. 2009; Unrath et al. 2010]. Associations of DTI-based changes with clinical parameters have been demonstrated in single studies. Patients with ALS with rapid progression had a significantly lower mean FA and any other FA measure in bihemispheric CST compared with controls in a study by Ciccarelli and colleagues [Ciccarelli et al. 2006]. Also in PLS, a significant correlation between FA values and disease progression rate was observed, suggesting that the tissue damage reflected in FA changes might contribute to the disease progression rate [Ciccarelli et al. 2009]. Combined use of diffusion tensor tractography of the CST and whole-brain voxel-based analysis allowed for comparison of the sensitivity of these techniques to detect white matter involvement in a study of patients with ALS, PLS and progressive muscular atrophy in early symptomatic stages [van der Graaff et al. 2011]. The voxel-based analysis demonstrated white matter involvement of varying extent in the different MND phenotypes, albeit in quite similar anatomical locations, with FA reductions being modest in progressive muscular atrophy and most extensive in PLS. In addition, the complementary approach of the whole brain-based application of different computerized MRI techniques in patients with MND seems to be promising, for example a combination of VBM and DTI. In such a combined macrostructural and microstructural MRI study, significant white matter differences between patients with ALS and controls were observed in the motor system (bilateral CST) and in extramotor brain areas, in part correlating with clinical parameters [Müller et al. 2011b]. Application of DTI to the assessment of spinal cord changes in association with ALS have been performed in 3 T MRI data and have demonstrated regionally distinct alterations along the brainstem and the cervical cord [Nair et al. 2010].

Figure 2.

Comparison of fractional anisotropy (FA) maps based on diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data of 20 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and 20 age- and gender-matched controls. Upper panel: group averaged FA maps of controls (left) and patients with ALS (right) in coronal (large) and axial/sagittal view. FA display threshold is 0.2. Lower panel: left: comparison between the ALS group and the controls by whole brain based statistical voxelwise comparison at group level, at p < 0.05 after correction for multiple comparisons. The areas with decreased FA in ALS are displayed, with the significance of the alterations coded by temperature of the color bar. Right: fiber tracking of the corticospinal tract (CST) in group-averaged DTI datasets. The underlying FA values were averaged and statistically compared. Differences between group-averaged ALS FA maps and group-averaged control FA maps were highly significant as indicated.

Computer-based magnetic resonance imaging: spectroscopy

Proton (1H) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) of the brain is an additional tool which has proven to be sensitive to cerebral pathology in ALS using common proton-based cerebral metabolites, that is, N-acetylaspartate (NAA), usually expressed as a ratio with creatine or choline [Turner et al. 2009], with higher field strengths of at least 3 T allowing better separation of metabolite signals. Most MRS studies were performed using a cross-sectional design [Kalra and Arnold, 2003], but single studies in a longitudinal design could demonstrate the potential of MRS to assess cerebral changes, although the subject numbers are commonly low. In an optimized 1H MRS study over 6 months, the patient group showed a significant NAA decline over time in the motor cortex areas of the clinically more and less affected hemisphere between the first measurement and that at 6 months and for the less affected hemisphere between the first measurement and that at 3 months. For the NAA ratio, a significant decline in the less affected hemisphere was observed from the first measurement to that at 3 months and 6 months, and from the measurement at 3 months to that at 6 months [Unrath et al. 2007]. However, due to the low level of standardization in data acquisition (e.g. volume-of-interest placement) and in postprocessing, the potential for MRS in larger-scale studies at multiple sites has to be considered as limited.

Computer-based magnetic resonance imaging: functional magnetic resonance imaging

For functional neuroimaging, the broad availability of functional MRI (fMRI), with a multitude of paradigms addressing motor and extra-motor (e.g. behavioral) function using blood oxygen level dependent imaging, has considerably increased the number of functional studies in severely restricted patients like those with ALS and has contributed to an exponential increase in scientific publications on MRI in MNDs over the last decades (see Lulé and colleagues for a review) [Lulé et al. 2009]. Within the concept of multiparametric MRI, that is the combination of different MRI-based applications, there are the first observations of altered cortical activity during visual, auditory and somatosensory stimulation by fMRI in patients with ALS compared with controls, each associated with structural white matter changes assessed by DTI in corresponding brain network areas [Lulé et al. 2010]. Despite the high potential of these task-based paradigms to address specific questions about motor or cognitive and other nonmotor functions, they are still biased by the limitations of physical disability. To date, fMRI is recommended for the neuroimaging approach in the assessment of cognitive network abnormalities in patients with MND [Filippi et al. 2010]. Currently, task-free fMRI as the unbiased investigation of the ‘resting state’ of discrete cortical networks, designed to analyze inter-regional correlations of spontaneous brain activity as measured by blood oxygen level dependent signal fluctuations in the dimension of time, has opened up the possibility of probing functional changes on a broader scale, which may then better reflect a more interconnected ‘network or system failure’ model of ALS pathogenesis [Turner et al. 2011]. An initial study confirmed the functional changes of the sensorimotor network in ALS [Mohammadi et al. 2009]. Subsequently, in a multiparametric approach, the combination of DTI and resting state-fMRI (rs-fMRI) implied that increased functional connectedness may even be associated with faster progression of disease, suggesting spread of disease along functional connections of the motor network [Verstraete et al. 2010]. The methodology of rs-fMRI data analysis is still being explored for its potential (e.g. for the investigation of multiple networks) and its limitations (e.g. the signal-to-noise ratio).

Future perspectives: preparing for clinical trials

Given these techniques are the most broadly available, technically most advanced and promising computerized MRI applications in the in vivo characterization of the brains of patients with ALS or other MNDs, there are current recommendations and many future perspectives. The recommendations are summarized in the EFNS guidelines [Filippi et al. 2010]. Here, advanced neuroimaging techniques such as volumetric analyses, DTI, MRS, or (rs-)fMRI do not have a role yet in the diagnosis or routine monitoring of MNDs (class IV, level GCPP). However, quantitative measurements of regional brain atrophy continue to be considered at a preliminary stage of development, but they need to be standardized and validated further in the context of longitudinal and normative studies. Measurement of cervical cord area needs more study data to be further assessed for its potential. The authors suggested that brain and spinal cord atrophy might be included as secondary endpoints in disease-modifying agent trials of MNDs, to further elucidate the mechanisms responsible for disability in these conditions. DTI and MRS may be useful in the assessment of UMN damage (DTI) or in the evaluation of MND progression and response to treatment (MRS), requiring further evaluation.

The future perspectives have been summarized in a recent position statement [Turner et al. 2011]. These authors recognized that interpretation of imaging data would only be possible with robust clinical information on patient characteristics, addressing reliability in terms of neurological accuracy and the aspect of the marked heterogeneity inherent to ALS in terms of disease localization, spread and progression. Accordingly, there is the need to balance a multiparametric MRI approach, increasing the potential biomarker yield, with simplicity, reproducibility and tolerability. As such, the four principal areas of MRI-based surrogate marker potential in ALS were identified: voxel-based morphometry of T1w images, DTI, rs-fMRI and MRS. The multiparametric approach was considered to be essential for the quality of the information gained, for example, DTI combined with morphometric or volumetric MRI analyses and rs-fMRI. The combination of measures from different techniques has the potential to improve the sensitivity and specificity of MRI, but increases statistical demands. Future studies involving these MRI techniques should be longitudinal, although the challenges of increasing physical disability during the disease course have to be taken into consideration. However, cross-sectional studies with smaller groups retain their value in the exploration of new MRI acquisition sequences or in combined studies with other technical tools different from neuroimaging.

For the known major single genes currently identified in ALS, that is SOD1, TDP-43, FUS and the hexanucleotide repeat on the chromosome 9p21 locus, the nature and time course of presymptomatic motor brain pathology and its presentation in MRI is completely unknown. The study of presymptomatic patients with pathological gene mutations known to be associated with ALS can be realized as the only way currently available to study structural and functional alterations prior to clinical onset. Here, studies in other genetic neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s disease may serve as examples [Klöppel et al. 2009]. In a prospective international study aimed at the identification of preclinical Huntington’s disease biomarkers, the potential of structural MRI as a biomarker was demonstrated by a reduction in striatal volume identifiable 15 years before the estimated time of disease diagnoses [Tabrizi et al. 2011]. In a similar approach to familial ALS – although the much more complex genetics and the much more heterogeneous phenotype presentation compared with Huntington’s disease is a highly relevant factor which cannot be ignored – it might be possible to identify neuroimaging-based ‘fingerprints’ for the early differential diagnostics of ALS so that MRI-based computational neuropathology is capable of identifying hallmarks of ALS in its early stages [Turner et al. 2011]. In this line of thought, it is of utmost importance to study in detail in a multicenter approach whether these MRI analysis techniques provide sufficiently detailed information to reliably identify ALS-related brain pathology in single patients or provide quantitative surrogate markers for disease progression usable in clinical trials [Grosskreutz et al. 2008].

Conclusion

In summary, computerized MRI analyses in MNDs are currently not techniques used for individual diagnosis. However, they have improved the anatomical understanding of pathomorphological alterations in gray and white matter in various MNDs and the changes in functional networks by quantitative comparisons between patients with MND and controls at group level. They have also established (combined) MRI protocols as a potential ‘dry’ surrogate marker for natural history studies with well defined patient groups and future disease-modifying multicenter trials. There is still the need for more longitudinal studies (in the very early stages of disease or when there is clinical uncertainty) and better standardization in the acquisition and postprocessing of computer-based neuroimaging data, which can be addressed by the establishment of strictly quality-controlled multicenter databases.

Footnotes

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Agosta F., Pagani E., Rocca M.A., Caputo D., Perini M., Salvi F., et al. (2007) Voxel-based morphometry study of brain volumetry and diffusivity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients with mild disability. Hum Brain Mapp 28: 1430–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agosta F., Chiò A., Cosottini M., De Stefano N., Falini A., Mascalchi M., et al. (2010) The present and the future of neuroimaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 31: 1769–1777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser P.J., Jones D.K. (2002) Diffusion-tensor MRI: theory, experimental design and data analysis – a technical review. NMR Biomed 15: 456–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli O., Behrens T.E., Altmann D.R., Orrell R.W., Howard R.S., Johansen-Berg H., et al. (2006) Probabilistic diffusion tractography: a potential tool to assess the rate of disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 129: 1859–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S., Kaufmann P., Shungu D.C., Mitsumoto H. (2003) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and primary lateral sclerosis: evidence-based diagnostic evaluation of the upper motor neuron. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 13: 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.L., Lomen-Hoerth C., Murphy J., Henry R.G., Kramer J.H., Miller B.L., Gorno-Tempini M.L. (2005) A voxel-based morphometry study of patterns of brain atrophy in ALS and ALS/FTLD. Neurology 65: 75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli O., Behrens T.E., Johansen-Berg H., Talbot K., Orrell R.W., Howard R.S., et al. (2009) Investigation of white matter pathology in ALS and PLS using tract-based spatial statistics. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 615–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comi G., Rovaris M., Leocani L. (1999) Review neuroimaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 6: 629–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi M., Agosta F., Abrahams S., Fazekas F., Grosskreutz J., Kalra S., et al. (2010) EFNS guidelines on the use of neuroimaging in the management of motor neuron diseases. Eur J Neurol 17: 526-e20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini N., Douaud G., Mackay C.E., Knight S., Talbot K., Turner M.R. (2010) Corpus callosum involvement is a consistent feature of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 75: 1645–1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosskreutz J., Peschel T., Unrath A., Dengler R., Ludolph A.C., Kassubek J. (2008) Whole brain-based computerized neuroimaging in ALS and other motor neuron disorders. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 9: 238–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht M.J., Fellner C., Schmid A., Neundörfer B., Fellner F.A. (2005) Cortical T2 signal shortening in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is not due to iron deposits. Neuroradiology 47(11): 805–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra S., Arnold D. (2003) Neuroimaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 4: 243–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassubek J., Juengling F.D., Baumgartner A., Unrath A., Ludolph A.C., Sperfeld A.D. (2007) Different regional brain volume loss in pure and complicated hereditary spastic paraparesis: a voxel-based morphometric study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 8: 328–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassubek J., Unrath A., Huppertz H.J., Lulé D., Ethofer T., Sperfeld A.D., et al. (2005) Global brain atrophy and corticospinal tract alterations in ALS, as investigated by voxel-based morphometry of 3-D MRI. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 6: 213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klöppel S., Henley S.M., Hobbs N.Z., Wolf R.C., Kassubek J., Tabrizi S.J., et al. (2009) Magnetic resonance imaging of Huntington’s disease: preparing for clinical trials. Neuroscience 164: 205–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C.M., Richardson M.P., Brooks D.J., Al-Chalabi A., Leigh P.N. (2000) Extramotor involvement in ALS: PET studies with the GABA(A) ligand [(11)C]flumazenil. Brain 123: 2289–2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lulé D., Diekmann V., Müller H.P., Kassubek J., Ludolph A.C., Birbaumer N. (2010) Neuroimaging of multimodal sensory stimulation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81: 899–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lulé D., Ludolph A.C., Kassubek J. (2009) MRI-based functional neuroimaging in ALS: an update. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 10: 258–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi B., Kollewe K., Samii A., Krampfl K., Dengler R., Münte T.F. (2009) Changes of resting state brain networks in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp Neurol 217: 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller H.P., Unrath A., Riecker A., Pinkhardt E.H., Ludolph A.C., Kassubek J. (2009) Intersubject variability in the analysis of diffusion tensor images at the group level: fractional anisotropy mapping and fiber tracking techniques. Magn Reson Imaging 27: 324–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller H.P., Lulé D., Unrath A., Ludolph A.C., Riecker A., Kassubek J. (2011a) Complementary image analysis of diffusion tensor imaging and 3-dimensional T1-weighted imaging: white matter analysis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuroimaging 21: 24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller H.P., Unrath A., Riecker A., Kassubek J. (2011b) Diffusion tensor imaging: analysis methods for group comparison in neurology. In: L’Abate L., Kaiser D.A. (eds), Handbook of Technology in Psychology, Psychiatry, and Neurology: Theory, Research, and Practice. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers, in press [Google Scholar]

- Nair G., Carew J.D., Usher S., Lu D., Hu X.P., Benatar M. (2010) Diffusion tensor imaging reveals regional differences in the cervical spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage 53: 576–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sach M., Winkler G., Glauche V., Liepert J., Heimbach B., Koch M.A., et al. (2004) Diffusion tensor MRI of early upper motor neuron involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 127: 340–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage C.A., Van Hecke W., Peeters R., Sijbers J., Robberecht W., Parizel P., et al. (2009) Quantitative diffusion tensor imaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: revisited. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 3657–3675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M.A., Statland J.M., Wolfe G.I., Barohn R.J. (2007) Primary lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 35: 291–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabrizi S.J., Scahill R.I., Durr A., Roos R.A., Leavitt B.R., Jones R., et al. (2011) Biological and clinical changes in premanifest and early stage Huntington’s disease in the TRACK-HD study: the 12-month longitudinal analysis. Lancet Neurol 10: 31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M., Ichiba T., Kondo S., Hirai S., Okamoto K. (2003) Cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism in patients with progressive dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol Res 25: 351–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M.R., Grosskreutz J., Kassubek J., Abrahams S., Agosta F., Benatar M., et al. (2011) Towards a neuroimaging biomarker in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 10: 400–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M.R., Leigh P.N. (2000) Positron emission tomography (PET) – its potential to provide surrogate markers in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 1(Suppl. 2): S17–S22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M.R., Kiernan M.C., Leigh P.N., Talbot K. (2009) Biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 8: 94–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unrath A., Ludolph A.C., Kassubek J. (2007) Brain metabolites in definite amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. A longitudinal proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Neurol 254: 1099–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unrath A., Ludolph A.C., Kassubek J. (2011) Alterations of the corpus callosum as an MR imaging based hallmark of motor neuron diseases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 32: E90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unrath A., Müller H.P., Riecker A., Ludolph A.C., Sperfeld A.D., Kassubek J. (2010) Whole brain-based analysis of regional white matter tract alterations in rare motor neuron diseases by diffusion tensor imaging. Hum Brain Mapp 31: 1727–1740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Graaff M.M., Sage C.A., Caan M.W., Akkerman E.M., Lavini C., Majoie C.B., et al. (2011) Upper and extra-motoneuron involvement in early motoneuron disease: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain 134: 1211–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraete E., van den Heuvel M.P., Veldink J.H., Blanken N., Mandl R.C., Hulshoff Pol H.E., et al. (2010) Motor network degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a structural and functional connectivity study. PLoS One 5: e13664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Melhem E.R. (2005) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and primary lateral sclerosis: the role of diffusion tensor imaging and other advanced MR-based techniques as objective upper motor neuron markers. Ann NY Acad Sci 1064: 61–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]